MaryAnn Bernal's Blog, page 230

October 10, 2014

Remains of Alexander the Great's Father Confirmed Found

by Rossella Lorenzi

Unequal greaves and the Scynthian gorytus

Theodore Antikas A team of Greek researchers has confirmed that bones found in a two-chambered royal tomb at Vergina, a town some 100 miles away from Amphipolis's mysterious burial mound, indeed belong to the Macedonian King Philip II, Alexander the Great's father.

How Did They Build the Pyramids? With Water! Find out how this seemingly impossible task might have been accomplished. The anthropological investigation examined 350 bones and fragments found in two larnakes, or caskets, of the tomb. It uncovered pathologies, activity markers and trauma that strongly contributed to the identification of the tomb's occupants.

Along with the cremated remains of Philip II, the burial, commonly known as Tomb II, also contained the bones of a woman warrior, possibly the daughter of the Skythian King Athea, Theodore Antikas, head of the Art-Anthropological research team of the Vergina excavation, told Discovery News.

PHOTOS: Female Sculptures Revealed in Greek Tomb

The findings will be announced on Friday at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. Accompanied by 3,000 digital color photographs and supported by X-ray computed tomography, scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray fluorescence, the research aims to settle a decades-old debate over the cremated skeleton.

Indeed, scholars have argued over those bones ever since Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos discovered the tomb in 1977-78. He excavated a large mound -- the Great Tumulus -- at Vergina on the advice of the English classicist Nicholas Hammond.

Among the monuments found within the tumulus were three tombs. One, called Tomb I, had been looted, but contained a stunning wall painting of the Rape of Persephone, along with fragmentary human remains.

PHOTOS: Great Archaeological Discoveries Ahead

Tomb II remained undisturbed and contained the almost complete cremated remains of a male skeleton in the main chamber and the cremated remains of a female in the antechamber. Grave goods included silver and bronze vessels, gold wreaths, weapons, armor and two gold larnakes.

Tomb III was also found unlooted, with a silver funerary urn that contained the bones of a young male, and a number of silver vessels and ivory reliefs.

Most of the scholarly debate concentrated on the occupants of Tomb II, with experts arguing that the occupants were either Philip II and Cleopatra or Meda, both his wives, or Philip III Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother, who assumed the throne after Alexander's death, with his wife Eurydice.

Analyzed by Antikas' team since 2009, the male and female bones have revealed peculiarities not previously seen or recorded.

"The individual suffered from frontal and maxillary sinusitis that might have been caused by an old facial trauma," Antikas said.

PHOTOS: Accidental Archaeological Discoveries

Such trauma could be related to an arrow that hit and blinded Philip II's right eye at the siege of Methone in 354 B.C. The Macedonian king survived and ruled for another 18 years before he was assassinated at the celebration of his daughter's wedding.

The anthropologists found further bone evidence to support the identification with Philip II, who being a warrior, suffered many wounds, as historical accounts testify.

"He had signs of chronic pathology on the visceral surface of several low thoracic ribs, indicating pleuritis," Antikas said.

He noted that the pathology may have been the effect of Philip's trauma when his right clavicle was shattered with a lance in 345 or 344 B.C.

Discovery News

Unequal greaves and the Scynthian gorytus

Theodore Antikas A team of Greek researchers has confirmed that bones found in a two-chambered royal tomb at Vergina, a town some 100 miles away from Amphipolis's mysterious burial mound, indeed belong to the Macedonian King Philip II, Alexander the Great's father.

How Did They Build the Pyramids? With Water! Find out how this seemingly impossible task might have been accomplished. The anthropological investigation examined 350 bones and fragments found in two larnakes, or caskets, of the tomb. It uncovered pathologies, activity markers and trauma that strongly contributed to the identification of the tomb's occupants.

Along with the cremated remains of Philip II, the burial, commonly known as Tomb II, also contained the bones of a woman warrior, possibly the daughter of the Skythian King Athea, Theodore Antikas, head of the Art-Anthropological research team of the Vergina excavation, told Discovery News.

PHOTOS: Female Sculptures Revealed in Greek Tomb

The findings will be announced on Friday at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. Accompanied by 3,000 digital color photographs and supported by X-ray computed tomography, scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray fluorescence, the research aims to settle a decades-old debate over the cremated skeleton.

Indeed, scholars have argued over those bones ever since Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos discovered the tomb in 1977-78. He excavated a large mound -- the Great Tumulus -- at Vergina on the advice of the English classicist Nicholas Hammond.

Among the monuments found within the tumulus were three tombs. One, called Tomb I, had been looted, but contained a stunning wall painting of the Rape of Persephone, along with fragmentary human remains.

PHOTOS: Great Archaeological Discoveries Ahead

Tomb II remained undisturbed and contained the almost complete cremated remains of a male skeleton in the main chamber and the cremated remains of a female in the antechamber. Grave goods included silver and bronze vessels, gold wreaths, weapons, armor and two gold larnakes.

Tomb III was also found unlooted, with a silver funerary urn that contained the bones of a young male, and a number of silver vessels and ivory reliefs.

Most of the scholarly debate concentrated on the occupants of Tomb II, with experts arguing that the occupants were either Philip II and Cleopatra or Meda, both his wives, or Philip III Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother, who assumed the throne after Alexander's death, with his wife Eurydice.

Analyzed by Antikas' team since 2009, the male and female bones have revealed peculiarities not previously seen or recorded.

"The individual suffered from frontal and maxillary sinusitis that might have been caused by an old facial trauma," Antikas said.

PHOTOS: Accidental Archaeological Discoveries

Such trauma could be related to an arrow that hit and blinded Philip II's right eye at the siege of Methone in 354 B.C. The Macedonian king survived and ruled for another 18 years before he was assassinated at the celebration of his daughter's wedding.

The anthropologists found further bone evidence to support the identification with Philip II, who being a warrior, suffered many wounds, as historical accounts testify.

"He had signs of chronic pathology on the visceral surface of several low thoracic ribs, indicating pleuritis," Antikas said.

He noted that the pathology may have been the effect of Philip's trauma when his right clavicle was shattered with a lance in 345 or 344 B.C.

Discovery News

Published on October 10, 2014 05:13

Burnt Magna Carta Read for First Time in 283 Years

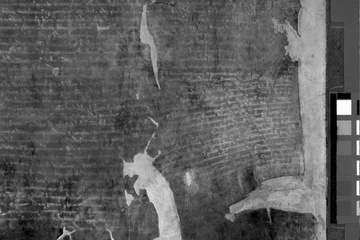

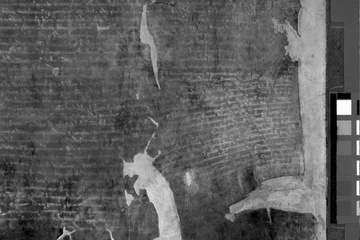

Using ultraviolet light, British Library scientists were able to photograph the text of the 1215 Burnt Magna Carta that is invisible to the human eye.

Credit: British More than 280 years after it was damaged in a fire, one of the original copies of the Magna Carta is legible again.

Written in 1215, the Magna Carta required the king of England — King John — to cede absolute power. Today, the Magna Carta is seen as a first step toward constitutional law rather than the hereditary power of royalty. There were four copies of the document created at the time. One, held by the British Library, was badly damaged in a fire in 1731.

Now, researchers have used a technique called multispectral imaging to decipher the text of the "Burnt Magna Carta" without touching or further damaging the delicate parchment. This imaging allowed conservation scientists to take pictures of the document that virtually erase the damage and show details of the parchment and text.

[image error]

[image error]

Using ultraviolet light, British Library scientists were able to photograph the text of the 1215 Burnt Magna Carta that is invisible to the human eye.

Credit: British Library View full size image

More than 280 years after it was damaged in a fire, one of the original copies of the Magna Carta is legible again.

Written in 1215, the Magna Carta required the king of England — King John — to cede absolute power. Today, the Magna Carta is seen as a first step toward constitutional law rather than the hereditary power of royalty. There were four copies of the document created at the time. One, held by the British Library, was badly damaged in a fire in 1731.

Now, researchers have used a technique called multispectral imaging to decipher the text of the "Burnt Magna Carta" without touching or further damaging the delicate parchment. This imaging allowed conservation scientists to take pictures of the document that virtually erase the damage and show details of the parchment and text.

"It was in such a terrible state, we couldn't read any of it, really," said British Library imaging scientist Christina Duffy. "It was actually quite a surprise that so much text was recovered." [See Images of the Recovered Magna Carta Text]

Damaged document

The imaging is part of the preparations for the 800th anniversary of the sealing of the Magna Carta, when Prince John imprinted his royal seal on the document and was bound by oath to abide by its demands. The British Library holds two of the original copies of the Magna Carta from 1215, including the burnt version. The other two copies are held at Lincoln Cathedral and Salisbury Cathedral.

On Feb. 3, 2015, the four copies will be displayed side-by-side at the British Library in London for the first time ever. The public can enter a lottery for free tickets to the viewing, which will be available to 1,215 lucky winners. Registration is available on the British Library website.

The Burnt Magna Carta has not been examined for decades, Duffy told Live Science. In the 1970s, it was set in a very secure frame, she said. That out-of-date frame has been removed in anticipation of the February 2015 anniversary, giving scientists the chance to get a closer look at the document.

Revisiting the text

The British Library team had no interest in trying to restore the smoke-damaged document, Duffy said, but wanted to preserve it as-is.

"There are different ways you can treat it," she said. "But a lot of them would be wet processes, so you might have to dampen certain areas, and we don't want to introduce any moisture at all to the charter."

Instead, the scientists used multispectral imaging, essentially photographing the burnt parchment in a variety of LED lights, spanning the spectrum from ultraviolet to infrared — outside the range of human vision.

"If you're interested in the ink, the ultraviolet light gives you the best information. If you are interested in the actual texture of the parchment itself, the infrared would be better," Duffy said. "You end up with multiple images of essentially the same thing, but giving you different information."

In these images, text that is invisible to the naked eye is suddenly visible. The Burnt Magna Carta is basically identical in text to the other three copies from 1215, Duffy said. The team is still processing the multispectral imagery and will conduct the same process on other old documents related to the Magna Carta, she said. The results will be displayed between March 13, 2015 and Sept. 1, 2015, in a British Library exhibit called "Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy."

Live Science

Published on October 10, 2014 05:06

Silver Tiara Among Treasures Discovered in Bronze Age Tomb

by Stephanie Pappas

A silver diadem discovered in a Spanish Bronze-Age tomb, perched atop the head of a female skeleton. The tomb is at the site of La Almoloya, which was a power center for the El Argar civilization of this era.

Credit: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB)

A Bronze Age woman buried in Spain wore a symbol of her wealth and power on her head: an elegant silver crown.

The silver circlet was one of several dozen precious items found in the woman's tomb, which she shared with a male adult. The tomb sits in the La Almoloya plateau, located in southeastern Spain. Between about 2200 B.C. and 1550 B.C., this site was a bustling political center, with multiple residential complexes and tombs.

La Almoloya was first discovered in 1944, and seems to have been the seat of the Bronze Age El Argar civilization, which is known for its sophisticated bronze and ceramic artifacts. Now, researchers from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona have excavated dozens of new buildings and 50 new tombs at the site, including the joint tomb holding the silver circlet. [See Photos of the Bronze Age Tomb and Treasures]

Tomb treasures

That tomb stands out because the man and woman inside are curled into flexed positions and surrounded by precious and semi-precious objects, the archaeologists said. Other than the woman's tiara, the tomb contained silverrings, earrings and bracelets, as well as a bronze dagger nailed to its handle with silver fastenings. A delicate ceramic cup was gilded with silver on the rim and exterior, representing some of the earliest silverwork seen on such a vessel, the researchers reported.

Some of the tomb treasures were rare, indeed. The researchers uncovered a metal punch, a tool used to create holes; it has a silver handle and bronze tip and is unlike any other item from the region and era that archaeologists have ever discovered. The tomb also contained four ear dilators, which would have been used to stretch the earlobes after piercing, like modern ear gauges. Two of the dilators were silver, and two were gold.

The silver circlet itself is an unusual find. Only four other diadems from the El Algar civilization have ever been discovered, the researchers said. None of those diadems remain in collections in Spain.

Power and wealth

The buildings found in La Almoloya are stone and mortar, with some stucco decorations. The site not only reveals Bronze Age construction techniques, but also hints at the political structure of the era, the researchers noted.

The treasure-filled tomb sits right next to another newly discovered structure, a high-ceiling hall about 750 square feet (70 square meters) in area. The hall is part of a palatial complex, which includes several other rooms.

Benches line the walls of the hall, offering seating for 64 people around a ceremonial fireplace and podium. The archaeology team suspects this hall was the Bronze Age version of a courtroom or conference room, used for hearings and government meetings. If so, it is the first Bronze Age government building ever discovered in Western Europe, the archaeologists reported.

Live Science

A silver diadem discovered in a Spanish Bronze-Age tomb, perched atop the head of a female skeleton. The tomb is at the site of La Almoloya, which was a power center for the El Argar civilization of this era.

Credit: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB)

A Bronze Age woman buried in Spain wore a symbol of her wealth and power on her head: an elegant silver crown.

The silver circlet was one of several dozen precious items found in the woman's tomb, which she shared with a male adult. The tomb sits in the La Almoloya plateau, located in southeastern Spain. Between about 2200 B.C. and 1550 B.C., this site was a bustling political center, with multiple residential complexes and tombs.

La Almoloya was first discovered in 1944, and seems to have been the seat of the Bronze Age El Argar civilization, which is known for its sophisticated bronze and ceramic artifacts. Now, researchers from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona have excavated dozens of new buildings and 50 new tombs at the site, including the joint tomb holding the silver circlet. [See Photos of the Bronze Age Tomb and Treasures]

Tomb treasures

That tomb stands out because the man and woman inside are curled into flexed positions and surrounded by precious and semi-precious objects, the archaeologists said. Other than the woman's tiara, the tomb contained silverrings, earrings and bracelets, as well as a bronze dagger nailed to its handle with silver fastenings. A delicate ceramic cup was gilded with silver on the rim and exterior, representing some of the earliest silverwork seen on such a vessel, the researchers reported.

Some of the tomb treasures were rare, indeed. The researchers uncovered a metal punch, a tool used to create holes; it has a silver handle and bronze tip and is unlike any other item from the region and era that archaeologists have ever discovered. The tomb also contained four ear dilators, which would have been used to stretch the earlobes after piercing, like modern ear gauges. Two of the dilators were silver, and two were gold.

The silver circlet itself is an unusual find. Only four other diadems from the El Algar civilization have ever been discovered, the researchers said. None of those diadems remain in collections in Spain.

Power and wealth

The buildings found in La Almoloya are stone and mortar, with some stucco decorations. The site not only reveals Bronze Age construction techniques, but also hints at the political structure of the era, the researchers noted.

The treasure-filled tomb sits right next to another newly discovered structure, a high-ceiling hall about 750 square feet (70 square meters) in area. The hall is part of a palatial complex, which includes several other rooms.

Benches line the walls of the hall, offering seating for 64 people around a ceremonial fireplace and podium. The archaeology team suspects this hall was the Bronze Age version of a courtroom or conference room, used for hearings and government meetings. If so, it is the first Bronze Age government building ever discovered in Western Europe, the archaeologists reported.

Live Science

Published on October 10, 2014 04:59

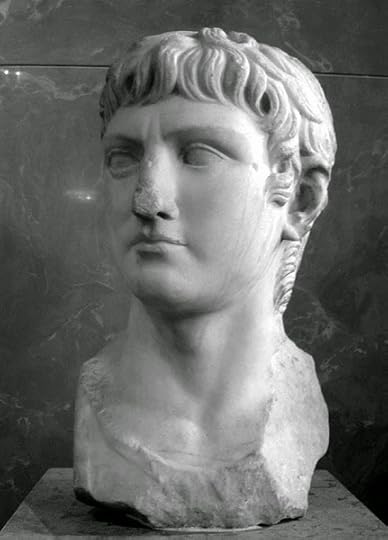

History Trivia - Germanicus, the best loved of Roman princes, dies of poisoning

October 10

19 Germanicus, the best loved of Roman princes, died of poisoning. On his deathbed he accuses Piso, the governor of Syria, of poisoning him.

1361 Prince Edward (Black Prince) married Joan Plantagenet. The "Fair Maid of Kent" was not considered the ideal wife for the heir of the English throne. Joan was the mother of Richard II.

1471 Battle of Brunkeberg in Stockholm: Sten Sture the Elder, the Regent of Sweden, with the help of farmers and miners, repelled an attack by Christian I, King of Denmark.

19 Germanicus, the best loved of Roman princes, died of poisoning. On his deathbed he accuses Piso, the governor of Syria, of poisoning him.

1361 Prince Edward (Black Prince) married Joan Plantagenet. The "Fair Maid of Kent" was not considered the ideal wife for the heir of the English throne. Joan was the mother of Richard II.

1471 Battle of Brunkeberg in Stockholm: Sten Sture the Elder, the Regent of Sweden, with the help of farmers and miners, repelled an attack by Christian I, King of Denmark.

Published on October 10, 2014 04:51

October 9, 2014

Which Universal Classic Monster Are You?

I am The Mummy

Congratulations, you are the Mummy! You go to great lengths for love and do so fearlessly. People like you for your taste in classic things and you exemplify the phrase “slow and steady wins the race.” Keep it up!

Find out who you are at Play Buzz

Published on October 09, 2014 08:42

History Trivia - Leif Ericson lands in North America

October 9

28 BC The Temple of Apollo was dedicated on the Palatine Hill in Rome.

768 Carloman I and Charlemagne were crowned Kings of The Franks.

1000 Leif Ericson, the great Norse explorer, became the first European to land in North America, which he called Vinland. The date is celebrated as Leif Ericson Day in Norway.

1529 Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was indicted for using his power illegally. His failure to secure the annulment of Henry VIII to Catherine of Aragon is widely perceived to have directly caused his downfall and arrest.

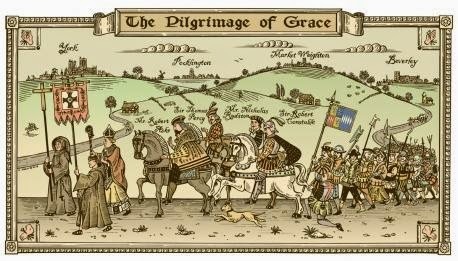

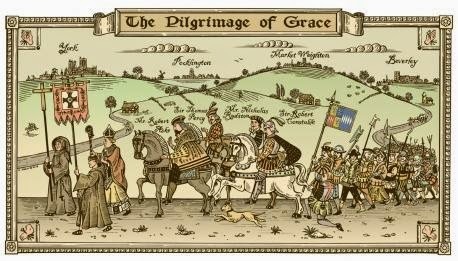

1536 The Pilgrimage of Grace, popular rising in York, Yorkshire, in protest against Henry VIII's break with the Roman Catholic Church and the Dissolution of the Monasteries, as well as other specific political, social and economic grievances, began.

28 BC The Temple of Apollo was dedicated on the Palatine Hill in Rome.

768 Carloman I and Charlemagne were crowned Kings of The Franks.

1000 Leif Ericson, the great Norse explorer, became the first European to land in North America, which he called Vinland. The date is celebrated as Leif Ericson Day in Norway.

1529 Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was indicted for using his power illegally. His failure to secure the annulment of Henry VIII to Catherine of Aragon is widely perceived to have directly caused his downfall and arrest.

1536 The Pilgrimage of Grace, popular rising in York, Yorkshire, in protest against Henry VIII's break with the Roman Catholic Church and the Dissolution of the Monasteries, as well as other specific political, social and economic grievances, began.

Published on October 09, 2014 06:02

October 8, 2014

How the Violin Got Its Shape

By Laura Geggel

Credit: potowizard | Shutterstock.com

The elegant shape of the violin evolved over a period of 400 years, largely due to the influence of four prominent families of instrument makers, a new study finds.

Researchers analyzed more than 9,000 violins, violas, cellos and double basses, and found that the shape of violins depended on the makers' family background, country of origin, the time period in which it was constructed, and how precisely the violins imitated the greats, such as the stringed instruments expertly crafted by Antonio Stradivari.

The first violins were made in Italy in the 16th century. Stradivari, one of history's most respected violin makers, lived in Cremona, in northern Italy, from 1644 to 1737. He crafted roughly 1,000 violins, including about 650 that have survived to this day. [In Images: Recreating a Legendary Stradivarius Violin]

In fact, the study found that the shape of modern violins has been disproportionately influenced by the work of Stradivari, said study researcher Daniel Chitwood, a scientist at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center in St. Louis.

"It's so well documented that there are violin makers who openly said they were copying Stradivari because his violin shapes were more desirable," Chitwood said.

Chitwood isn't a master violin maker; he's a plant researcher who studies developmental genetics but also plays viola in his spare time. He typically studies how plant genetics relate to the shapes of leaves.

In the new study, he used similar techniques to examine how the "traits" of violins, or their shapes, changed over time. "Really, violins are just a trait of human beings, just as plants have a trait," Chitwood told Live Science.

Some imitations are so exact that, in a separate study pitting new violins against the ones of the old masters, expert violin soloists could not distinguish between old and new violins. The soloists also preferred the new violins to the old ones, surprising musicians everywhere, the study, published in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found.

[image error] A mosaic of more than 5,000 violin images that the researcher examined in the study.

A mosaic of more than 5,000 violin images that the researcher examined in the study.

Credit: Daniel Chitwood

View full size image"[Stradivarius] are exceptional violins, but they're not always the best violin," Chitwood said.

When and where a violin was made also factored heavily into the instrument's shape. "These people couldn't help but be born in Cremona, or Paris or London," Chitwood said. "The instruments that they produced were shaped by where they were in history and where they were at."

Violin making also tended to be a family business passed down through the generations, so "human relatedness was also contributing to the different violin shapes throughout history," Chitwood added. For instance, the brothers Nicolò and Gennaro Gagliano, who lived in Italy during the 1700s, made similarly shaped violins.

To assess the evolution of violin shapes, Chitwood relied on images from online sales of rare and valuable violins. By analyzing the outlines of the instruments, Chitwood found four main "blueprints" influenced by master instrument-making families, including Stradivari, the Italian Giovanni Paolo Maggini (1580-1630), the Italian Amati family and the Austrian Jacob Stainer (1617-1683). [Creative Genius: The World's Greatest Minds]

While examining the outlines of violins, Chitwood also found that using his analysis, the shape of a viola is indistinguishable from that of a violin about 63 percent of the time. A viola player himself, Chitwood said the instrument should probably be larger to accommodate its deeper range but that instrument makers decided to limit its size so that it could be played under the chin, like a violin, instead of between the legs, like a cello.

If made any larger, the viola would likely cause backaches in many viola players, he said.

"We wrongly decided that we're going to put them under our chin," Chitwood said. "But the real solution is that we should be playing violas between our knees."

Shape and sound

"This study looks at evolutionary patterns in that outline over the centuries," said Jim Woodhouse, a professor of engineering at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the study. "It reveals some fairly clear trends, and also clear clusters of related shapes."

The arching patterns and thickness of the wood used to make a violin's plates, as well as the plates' wood properties, are vital to the instrument's acoustics. In contrast, the shape of a violin doesn't have a strong influence over its sound, which means crafters can experiment with how they construct the body of the instrument.

"As the author [of the new study] acknowledges, outline shape has not received a lot of attention from scientists looking into the physics of how the violin works," Woodhouse said. "This is not an omission; it is based on a clear expectation that outline shape probably has a rather minor importance to sound. Other aspects of the violin structure are far more important."

Violin aficionados interested in Chitwood's work can download a poster of the violin images used in the study.

Live Science

Credit: potowizard | Shutterstock.com

The elegant shape of the violin evolved over a period of 400 years, largely due to the influence of four prominent families of instrument makers, a new study finds.

Researchers analyzed more than 9,000 violins, violas, cellos and double basses, and found that the shape of violins depended on the makers' family background, country of origin, the time period in which it was constructed, and how precisely the violins imitated the greats, such as the stringed instruments expertly crafted by Antonio Stradivari.

The first violins were made in Italy in the 16th century. Stradivari, one of history's most respected violin makers, lived in Cremona, in northern Italy, from 1644 to 1737. He crafted roughly 1,000 violins, including about 650 that have survived to this day. [In Images: Recreating a Legendary Stradivarius Violin]

In fact, the study found that the shape of modern violins has been disproportionately influenced by the work of Stradivari, said study researcher Daniel Chitwood, a scientist at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center in St. Louis.

"It's so well documented that there are violin makers who openly said they were copying Stradivari because his violin shapes were more desirable," Chitwood said.

Chitwood isn't a master violin maker; he's a plant researcher who studies developmental genetics but also plays viola in his spare time. He typically studies how plant genetics relate to the shapes of leaves.

In the new study, he used similar techniques to examine how the "traits" of violins, or their shapes, changed over time. "Really, violins are just a trait of human beings, just as plants have a trait," Chitwood told Live Science.

Some imitations are so exact that, in a separate study pitting new violins against the ones of the old masters, expert violin soloists could not distinguish between old and new violins. The soloists also preferred the new violins to the old ones, surprising musicians everywhere, the study, published in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found.

[image error]

A mosaic of more than 5,000 violin images that the researcher examined in the study.

A mosaic of more than 5,000 violin images that the researcher examined in the study.Credit: Daniel Chitwood

View full size image"[Stradivarius] are exceptional violins, but they're not always the best violin," Chitwood said.

When and where a violin was made also factored heavily into the instrument's shape. "These people couldn't help but be born in Cremona, or Paris or London," Chitwood said. "The instruments that they produced were shaped by where they were in history and where they were at."

Violin making also tended to be a family business passed down through the generations, so "human relatedness was also contributing to the different violin shapes throughout history," Chitwood added. For instance, the brothers Nicolò and Gennaro Gagliano, who lived in Italy during the 1700s, made similarly shaped violins.

To assess the evolution of violin shapes, Chitwood relied on images from online sales of rare and valuable violins. By analyzing the outlines of the instruments, Chitwood found four main "blueprints" influenced by master instrument-making families, including Stradivari, the Italian Giovanni Paolo Maggini (1580-1630), the Italian Amati family and the Austrian Jacob Stainer (1617-1683). [Creative Genius: The World's Greatest Minds]

While examining the outlines of violins, Chitwood also found that using his analysis, the shape of a viola is indistinguishable from that of a violin about 63 percent of the time. A viola player himself, Chitwood said the instrument should probably be larger to accommodate its deeper range but that instrument makers decided to limit its size so that it could be played under the chin, like a violin, instead of between the legs, like a cello.

If made any larger, the viola would likely cause backaches in many viola players, he said.

"We wrongly decided that we're going to put them under our chin," Chitwood said. "But the real solution is that we should be playing violas between our knees."

Shape and sound

"This study looks at evolutionary patterns in that outline over the centuries," said Jim Woodhouse, a professor of engineering at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, who was not involved in the study. "It reveals some fairly clear trends, and also clear clusters of related shapes."

The arching patterns and thickness of the wood used to make a violin's plates, as well as the plates' wood properties, are vital to the instrument's acoustics. In contrast, the shape of a violin doesn't have a strong influence over its sound, which means crafters can experiment with how they construct the body of the instrument.

"As the author [of the new study] acknowledges, outline shape has not received a lot of attention from scientists looking into the physics of how the violin works," Woodhouse said. "This is not an omission; it is based on a clear expectation that outline shape probably has a rather minor importance to sound. Other aspects of the violin structure are far more important."

Violin aficionados interested in Chitwood's work can download a poster of the violin images used in the study.

Live Science

Published on October 08, 2014 13:53

Cave paintings in Indonesia suggest art came out of Africa

Ghostly hand markings and animals in Sulawesi caves are much older than thought, pushing back probable date for origin of art

by Ian Sample

by Ian Sample

Researchers who dated the cave paintings in Sulawesi say they open up the possibility that art spread from Africa to both Asia and Europe. Video: NaturePaintings of wild animals and hand markings left by adults and children on cave walls in Indonesia are at least 35,000 years old, making them some of the oldest artworks known.

The rock art was originally discovered in caves on the island of Sulawesi in the 1950s, but dismissed as younger than 10,000 years old because scientists thought older paintings could not possibly survive in a tropical climate.

But fresh analysis of the pictures by an Australian-Indonesian team has stunned researchers by dating one hand marking to at least 39,900 years old, and two paintings of animals, a pig-deer or babirusa, and another animal, probably a wild pig, to at least 35,400 and 35,700 years ago respectively.

The work reveals that rather than Europe being at the heart of an explosion of creative brilliance when modern humans arrived from Africa, the early settlers of Asia were creating their own artworks at the same time or even earlier.

Archaeologists have not ruled out that the different groups of colonising humans developed their artistic skills independently of one another, but an enticing alternative is that the modern human ancestors of both were artists before they left the African continent.

“Our discovery on Sulawesi shows that cave art was made at opposite ends of the Pleistocene Eurasian world at about the same time, suggesting these practices have deeper origins, perhaps in Africa before our species left this continent and spread across the globe,” said Dr Maxime Aubert, an archaeologist at the University of Wollongong.

The paintings adorn the walls of caves and shelters at the foot of spectacular limestone towers that rise up from the surrounding rice fields near Maros in southwestern Sulawesi. The caves enthralled the Victorian naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who spent months in Maros collecting butterflies, though he appeared not to have spotted the abundant rock art, said Dr Adam Brumm, a co-author on the study at Wollongong.

A babirusa or ‘deer-pig’ and a hand stencil. Hunter-gatherers preyed on the strange and unique land mammals that evolved in isolation on Sulawesi. Photograph: Kinez Riza The paintings were made with the natural mineral pigment ochre – probably ironstone haematite – which the hunter-gatherers ground to a powder and mixed with water or other liquids to create paint. Long ago, the walls and ceilings of the caves might have been covered with images that provide a window into the minds of the Ice Age occupants.

A babirusa or ‘deer-pig’ and a hand stencil. Hunter-gatherers preyed on the strange and unique land mammals that evolved in isolation on Sulawesi. Photograph: Kinez Riza The paintings were made with the natural mineral pigment ochre – probably ironstone haematite – which the hunter-gatherers ground to a powder and mixed with water or other liquids to create paint. Long ago, the walls and ceilings of the caves might have been covered with images that provide a window into the minds of the Ice Age occupants.

Common among the artworks are ghostly hand markings made by blowing, spraying or spitting a mouthful of paint over an outstretched hand. The result – a hand stencil, the negative of a conventional print made by dipping the hand in paint – was an enduring personal signature on the cave wall.

“It remains a mystery what hand stencils meant to the prehistoric artists of Sulawesi, and why they created them in such abundance,” said Brumm.

The researchers dated 12 hand stencils and two figurative paintings of animals in seven caves near Maros. The most recent hand stencil was created around 17,400 years ago, according to details published in Nature.

“The paintings of the wild animals are most fascinating because it is clear they were of particular interest to the artists themselves,” said Brumm. The hunter-gatherers preyed on the strange and unique land mammals that evolved in isolation on Sulawesi, an ancient island that has been called the Madagascar of Indonesia.

While most of the animals in the paintings are identifiable, the artists often exaggerated aspects of the beasts, perhaps to accentuate features that interested them, said Brumm. “The feet are usually dainty appendages that were evidently painted with exquisite care, whereas the bodies are huge and bulbous, almost balloon-like in form giving some animal images an otherworldly appearance. In a few cases, the actual ground surface beneath the animals is also depicted, which is very rare worldwide. The paintings are feats of great imagination and they provide the first real insight into the artistic culture and symbolic conventions of early modern humans in Asia.”

The focus on Europe as the origin of art arose after the discovery of occasionally exquisite ancient paintings in caves across the continent. The oldest rock art – a smudged red disk on a cave wall at El Castillo in Spain – was painted at least 41,000 years ago. The breathtaking charcoal drawings of horses and rhinos at the Chauvet caves in the Ardeche in Southern France are at least 30,000 years old.

To date the Indonesian paintings, Aubert and his colleagues looked at calcium carbonate deposits known as “cave popcorn” that formed as mineral-rich water trickled down the cave walls. The deposits contain low levels of radioactive uranium which decays into thorium at a known rate, providing an effective geological clock. The age of cave popcorn that formed on top of paintings gave the researchers a minimum age for the images, while samples from underneath the cave art gave them maximum ages.

In an accompanying article, Wil Roebroeks, an expert in human origins at Leiden University in the Netherlands, writes: “This spectacular finding suggests that the making of images on cave walls was already a widely shared practice 40,000 years ago.”

Chris Stringer, head of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, said: “These exciting discoveries allow us to move away from Eurocentric ideas on the development of figurative art to consider the alternative possibility that such artistic expression was a fundamental part of human nature 60,000 years ago, when modern humans not only occupied most of Africa but were beginning to disperse out towards Europe and the Far East.

“When modern humans colonised Sulawesi at least 50,000 years ago as a precursor to reaching New Guinea and Australia, they were probably already producing these kinds of depictions. I predict that even older examples of cave art will be discovered on Sulawesi, and in mainland Asia, and ultimately in our African homeland dating to more than 60,000 years ago.”

The Guardian

by Ian Sample

by Ian SampleResearchers who dated the cave paintings in Sulawesi say they open up the possibility that art spread from Africa to both Asia and Europe. Video: NaturePaintings of wild animals and hand markings left by adults and children on cave walls in Indonesia are at least 35,000 years old, making them some of the oldest artworks known.

The rock art was originally discovered in caves on the island of Sulawesi in the 1950s, but dismissed as younger than 10,000 years old because scientists thought older paintings could not possibly survive in a tropical climate.

But fresh analysis of the pictures by an Australian-Indonesian team has stunned researchers by dating one hand marking to at least 39,900 years old, and two paintings of animals, a pig-deer or babirusa, and another animal, probably a wild pig, to at least 35,400 and 35,700 years ago respectively.

The work reveals that rather than Europe being at the heart of an explosion of creative brilliance when modern humans arrived from Africa, the early settlers of Asia were creating their own artworks at the same time or even earlier.

Archaeologists have not ruled out that the different groups of colonising humans developed their artistic skills independently of one another, but an enticing alternative is that the modern human ancestors of both were artists before they left the African continent.

“Our discovery on Sulawesi shows that cave art was made at opposite ends of the Pleistocene Eurasian world at about the same time, suggesting these practices have deeper origins, perhaps in Africa before our species left this continent and spread across the globe,” said Dr Maxime Aubert, an archaeologist at the University of Wollongong.

The paintings adorn the walls of caves and shelters at the foot of spectacular limestone towers that rise up from the surrounding rice fields near Maros in southwestern Sulawesi. The caves enthralled the Victorian naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who spent months in Maros collecting butterflies, though he appeared not to have spotted the abundant rock art, said Dr Adam Brumm, a co-author on the study at Wollongong.

A babirusa or ‘deer-pig’ and a hand stencil. Hunter-gatherers preyed on the strange and unique land mammals that evolved in isolation on Sulawesi. Photograph: Kinez Riza The paintings were made with the natural mineral pigment ochre – probably ironstone haematite – which the hunter-gatherers ground to a powder and mixed with water or other liquids to create paint. Long ago, the walls and ceilings of the caves might have been covered with images that provide a window into the minds of the Ice Age occupants.

A babirusa or ‘deer-pig’ and a hand stencil. Hunter-gatherers preyed on the strange and unique land mammals that evolved in isolation on Sulawesi. Photograph: Kinez Riza The paintings were made with the natural mineral pigment ochre – probably ironstone haematite – which the hunter-gatherers ground to a powder and mixed with water or other liquids to create paint. Long ago, the walls and ceilings of the caves might have been covered with images that provide a window into the minds of the Ice Age occupants.Common among the artworks are ghostly hand markings made by blowing, spraying or spitting a mouthful of paint over an outstretched hand. The result – a hand stencil, the negative of a conventional print made by dipping the hand in paint – was an enduring personal signature on the cave wall.

“It remains a mystery what hand stencils meant to the prehistoric artists of Sulawesi, and why they created them in such abundance,” said Brumm.

The researchers dated 12 hand stencils and two figurative paintings of animals in seven caves near Maros. The most recent hand stencil was created around 17,400 years ago, according to details published in Nature.

“The paintings of the wild animals are most fascinating because it is clear they were of particular interest to the artists themselves,” said Brumm. The hunter-gatherers preyed on the strange and unique land mammals that evolved in isolation on Sulawesi, an ancient island that has been called the Madagascar of Indonesia.

While most of the animals in the paintings are identifiable, the artists often exaggerated aspects of the beasts, perhaps to accentuate features that interested them, said Brumm. “The feet are usually dainty appendages that were evidently painted with exquisite care, whereas the bodies are huge and bulbous, almost balloon-like in form giving some animal images an otherworldly appearance. In a few cases, the actual ground surface beneath the animals is also depicted, which is very rare worldwide. The paintings are feats of great imagination and they provide the first real insight into the artistic culture and symbolic conventions of early modern humans in Asia.”

The focus on Europe as the origin of art arose after the discovery of occasionally exquisite ancient paintings in caves across the continent. The oldest rock art – a smudged red disk on a cave wall at El Castillo in Spain – was painted at least 41,000 years ago. The breathtaking charcoal drawings of horses and rhinos at the Chauvet caves in the Ardeche in Southern France are at least 30,000 years old.

To date the Indonesian paintings, Aubert and his colleagues looked at calcium carbonate deposits known as “cave popcorn” that formed as mineral-rich water trickled down the cave walls. The deposits contain low levels of radioactive uranium which decays into thorium at a known rate, providing an effective geological clock. The age of cave popcorn that formed on top of paintings gave the researchers a minimum age for the images, while samples from underneath the cave art gave them maximum ages.

In an accompanying article, Wil Roebroeks, an expert in human origins at Leiden University in the Netherlands, writes: “This spectacular finding suggests that the making of images on cave walls was already a widely shared practice 40,000 years ago.”

Chris Stringer, head of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, said: “These exciting discoveries allow us to move away from Eurocentric ideas on the development of figurative art to consider the alternative possibility that such artistic expression was a fundamental part of human nature 60,000 years ago, when modern humans not only occupied most of Africa but were beginning to disperse out towards Europe and the Far East.

“When modern humans colonised Sulawesi at least 50,000 years ago as a precursor to reaching New Guinea and Australia, they were probably already producing these kinds of depictions. I predict that even older examples of cave art will be discovered on Sulawesi, and in mainland Asia, and ultimately in our African homeland dating to more than 60,000 years ago.”

The Guardian

Published on October 08, 2014 13:45

History Trivia - Charles the Bald defeated at the Battle of Andernach

October 8

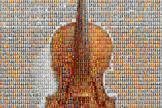

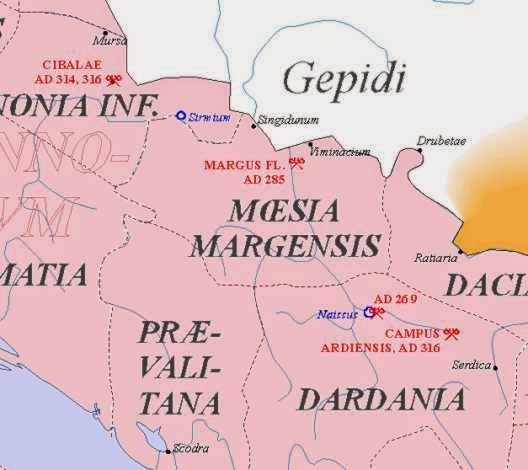

314 Roman Emperor Licinius was defeated by Constantine I at the Battle of Cibalae, losing his European territories. Co-author of the Edict of Milan that granted official toleration to Christians in the Roman Empire, for the majority of his reign he was the rival of Constantine I until he was finally defeated at the Battle of Adrianople, and was executed on Constantine's orders.

451 the fourth Ecumenical Council of the Roman Catholic Church ruled that Jesus Christ is "in two natures" in opposition to the doctrine of Monophysitism.

876 Charles the Bald is defeated at the Battle of Andernach.

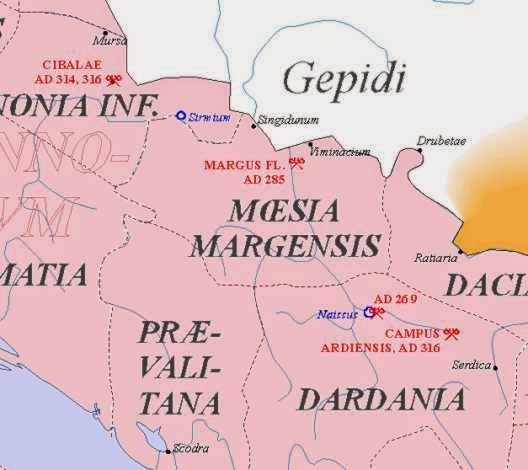

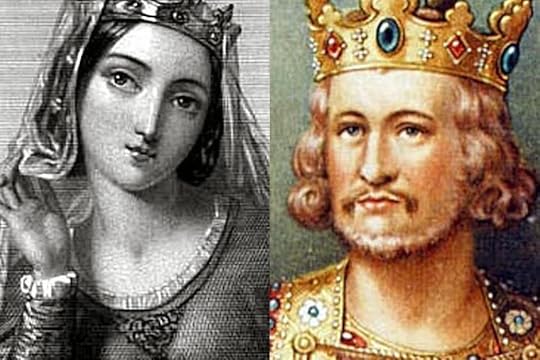

1200 Isabella of Angoulême, second wife of King John, was crowned Queen consort of England. Isabella had five children by the king including his heir Henry who succeeded John as Henry III of England. In 1220 Isabella married Hugh X of Lusignan, Count of La Marche, by whom she had another nine children.

314 Roman Emperor Licinius was defeated by Constantine I at the Battle of Cibalae, losing his European territories. Co-author of the Edict of Milan that granted official toleration to Christians in the Roman Empire, for the majority of his reign he was the rival of Constantine I until he was finally defeated at the Battle of Adrianople, and was executed on Constantine's orders.

451 the fourth Ecumenical Council of the Roman Catholic Church ruled that Jesus Christ is "in two natures" in opposition to the doctrine of Monophysitism.

876 Charles the Bald is defeated at the Battle of Andernach.

1200 Isabella of Angoulême, second wife of King John, was crowned Queen consort of England. Isabella had five children by the king including his heir Henry who succeeded John as Henry III of England. In 1220 Isabella married Hugh X of Lusignan, Count of La Marche, by whom she had another nine children.

Published on October 08, 2014 06:14

October 7, 2014

Dinosaur Arms to Bird Wings: It's All in the Wrist

by Stuart Gary

One of the last niggling doubts about the link between dinosaurs and birds may be settled by a new study that shows how bird wrists evolved from those of their dinosaur predecessors.

One of the last niggling doubts about the link between dinosaurs and birds may be settled by a new study that shows how bird wrists evolved from those of their dinosaur predecessors.

The study, reported in the Journal PLOS Biology , shows how nine dinosaurian wrist bones were reduced over millions of years of evolution to just four wrist bones in modern day birds.

"This discovery clarifies how dinosaur arms became bird wings," said one of the study's authors, Dr Alexander Vargas of the University of Chile in Santiago.

A huge triceratops skeleton was found in Wyoming! Researchers are saying it's not a triceratops -- that dinosaur never existed. "It shows that some bones fused, other bones disappeared, and one bone disappeared and then reappeared in evolution."

Skeletal similarities between theropod dinosaurs and birds provide some of the strongest evidence showing how birds developed from dinosaurs. But the evolution of straight dinosaur wrists into hyperflexible wrists allowing birds to fold their wings when not flying, has remained a point of contention between palaeontologists and some developmental biologists.

Among the structures in question is a half-moon shaped wrist bone called the semilunate which is found in dinosaurs and looks very similar to a wrist bone also found in birds.

The semilunate originated as two separate dinosaur bones which eventually fused into a single bone. However some developmental biologists claim it evolved as a single bone in birds, and so isn't the same bone as that found in dinosaurs.

To help settle the debate, Vargas and colleagues examined the wrist bones of dinosaur fossils in the collections from several museums, and compared them to new developmental data from seven different species of modern birds.

"We developed a new technique called whole-mount immunostaining, which allows us to observe skeleton development better than ever before, including the expression of proteins inside embryonic cartilage," said Vargas.

Modern Birds Are Really Baby Dinosaurs

The technique allowed the authors to determine that the embryonic semilunate in birds evolves as two separate cartilages which fuse into a single bone, consistent with what palaeontologists had been saying.

"These findings eliminate persistent doubts that existed over exactly how the bones of the wrist evolved, and iron out arguments about wrist development being incompatible with birds originating from dinosaurs," said Vargas.

The study also produced an interesting surprise for the research team when they discovered a wrist bone called the pisiform, which was present in early sauropod (four-legged, long-tailed, long-necked) dinosaurs, but had disappeared in later theropod (two-legged, two-armed) dinosaurs.

The authors found the pisiform had reappeared in early birds, probably as an adaptation for flight, where it allows transmission of force on the downstroke while restricting flexibility on the upstroke.

"We think the pisiform was lost when dinosaurs became bipedal," said Vargas. "Quadrupedal animals used this bone because they walk with their forelimbs, but bipedal dinosaurs no longer walked with their forelimbs and lost the bone. However they regained it when they began using their forelimbs for locomotion in flight."

Top 10 Largest Dinosaurs

This is a compelling scenario for a rare case of evolutionary reversal, said Professor Mike Archer of the University of New South Wales, who was not involved in the study.

"That's the most fascinating thing coming out of this work, because all of a sudden we're understanding how complex and yet how flexible and deliciously plastic embryological development can be," said Archer.

"There may be a gene lying around dormant and doing nothing, which suddenly gets kick-started and produces a structure that had been lost in the ancestor of the same animal."

Discovery News

One of the last niggling doubts about the link between dinosaurs and birds may be settled by a new study that shows how bird wrists evolved from those of their dinosaur predecessors.

One of the last niggling doubts about the link between dinosaurs and birds may be settled by a new study that shows how bird wrists evolved from those of their dinosaur predecessors.The study, reported in the Journal PLOS Biology , shows how nine dinosaurian wrist bones were reduced over millions of years of evolution to just four wrist bones in modern day birds.

"This discovery clarifies how dinosaur arms became bird wings," said one of the study's authors, Dr Alexander Vargas of the University of Chile in Santiago.

A huge triceratops skeleton was found in Wyoming! Researchers are saying it's not a triceratops -- that dinosaur never existed. "It shows that some bones fused, other bones disappeared, and one bone disappeared and then reappeared in evolution."

Skeletal similarities between theropod dinosaurs and birds provide some of the strongest evidence showing how birds developed from dinosaurs. But the evolution of straight dinosaur wrists into hyperflexible wrists allowing birds to fold their wings when not flying, has remained a point of contention between palaeontologists and some developmental biologists.

Among the structures in question is a half-moon shaped wrist bone called the semilunate which is found in dinosaurs and looks very similar to a wrist bone also found in birds.

The semilunate originated as two separate dinosaur bones which eventually fused into a single bone. However some developmental biologists claim it evolved as a single bone in birds, and so isn't the same bone as that found in dinosaurs.

To help settle the debate, Vargas and colleagues examined the wrist bones of dinosaur fossils in the collections from several museums, and compared them to new developmental data from seven different species of modern birds.

"We developed a new technique called whole-mount immunostaining, which allows us to observe skeleton development better than ever before, including the expression of proteins inside embryonic cartilage," said Vargas.

Modern Birds Are Really Baby Dinosaurs

The technique allowed the authors to determine that the embryonic semilunate in birds evolves as two separate cartilages which fuse into a single bone, consistent with what palaeontologists had been saying.

"These findings eliminate persistent doubts that existed over exactly how the bones of the wrist evolved, and iron out arguments about wrist development being incompatible with birds originating from dinosaurs," said Vargas.

The study also produced an interesting surprise for the research team when they discovered a wrist bone called the pisiform, which was present in early sauropod (four-legged, long-tailed, long-necked) dinosaurs, but had disappeared in later theropod (two-legged, two-armed) dinosaurs.

The authors found the pisiform had reappeared in early birds, probably as an adaptation for flight, where it allows transmission of force on the downstroke while restricting flexibility on the upstroke.

"We think the pisiform was lost when dinosaurs became bipedal," said Vargas. "Quadrupedal animals used this bone because they walk with their forelimbs, but bipedal dinosaurs no longer walked with their forelimbs and lost the bone. However they regained it when they began using their forelimbs for locomotion in flight."

Top 10 Largest Dinosaurs

This is a compelling scenario for a rare case of evolutionary reversal, said Professor Mike Archer of the University of New South Wales, who was not involved in the study.

"That's the most fascinating thing coming out of this work, because all of a sudden we're understanding how complex and yet how flexible and deliciously plastic embryological development can be," said Archer.

"There may be a gene lying around dormant and doing nothing, which suddenly gets kick-started and produces a structure that had been lost in the ancestor of the same animal."

Discovery News

Published on October 07, 2014 12:46