'Nathan Burgoine's Blog, page 5

February 25, 2025

Tabletop Tuesday — Triad Blood and Mutants & Masterminds: Anders Hake

It’s Tuesday, and the second piece my attempt at a tabletop role-playing-game set in the Triad world—or, more to the point—using Green Ronin’s Mutants & Masterminds system, treating the Triad world as a setting. Last week, I attempted to stat up Curtis Baird, the first of my three main characters from the novels, the wizard; I’m back again this week with the demon of the group, Anders Hake.

Who, for whatever reason, has the most fans among readers. I mean, he’s an Id-driven lust demon, so maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise, but let’s see if I can give him all the abilities I gave him in the stories—or, at least, some of them—what he would have had before he formed the triad with Luc and Curtis.

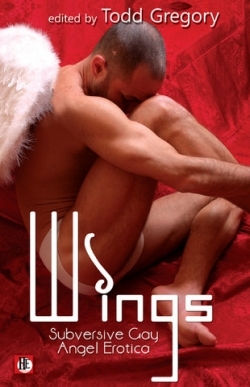

Originally, as I mentioned last week, the Triad boys came about for a single short story for an anthology—Blood Sacraments—but then the editor, Todd Gregory, reached out about a new anthology, Wings, focused on gay angel erotica, and I couldn’t help but think of the demon I’d written in the earlier story, Anders, and so… Anders met an angel, one who promised he could undo his demonic nature.

Given that was the theme of that story, however, I ended up being pretty specific about the various things Anders could do as a demon—what with the angel having told him he needed to turn from his demonic side if he wanted to recover his soul, it behooved me to make a pretty thorough list of what that was. Once again, however, Mutants & Masterminds proved itself to be super-flexible, and I ended up finding something for every power I’d given Anders. Seriously, the flexibility of Mutants & Masterminds really is impressive, but I’ve talked about that before, I don’t need to do it again.

(Amusingly, a year later, Todd Gregory would edit another anthology around demonic gay erotica, and I’d got to play with Anders again.)

Anders Hake, Packless Incubus (PL 8) Artwork by the awesome Micah.

Artwork by the awesome Micah.Cis Male, Appears ~30-40 years old, Height ~1.85m, Weight ~90kg, Brown eyes, Brown hair

Group Affiliation: None, Base of Operations: Ottawa

Abilities: Str 4, Sta 4, Agi 0, Dex 0, Fgt 3, Int 0, Awe 2, Pre 6 (26 points)

Powers:

Shapeshifting, Array with: Allure: Morph 2, Limited to male forms an individual finds attractive; Enhanced Advantages: Attractive 2, Fascinate (Persuasion); (8 Points, plus 2 points of Alternate Effects)Allure Reversed: Concealment 5 (All Sight, Hearing, Partial, Passive), Enhanced Advantage 1 (Hide in Plain Sight), Enhanced Skill 4 (Stealth 8); Quirk: Only affects those with minds (1 Point) Demonic Form: Claws (Penetrating 5 on Strength Damage), Accurate 1, Enhanced Strength 1 (1 point) Hellfire: Reaction Damage 2, Penetrating, Fades (4/R) (8 Points)Lust Demon: Speed 2, Enhanced Abilities (Strength 2, Presence 2, Stamina 2), Enhanced Advantages (Diehard, Improved Initiative), Immunity 1 (Aging; Quirk: linked to having “enough” soul), Protection 4 (20 points)Predator Senses: Senses 2 (Darkvision, Acute Olfactory) (2 Points)Shadow-walk: Movement 1 (Dimension—the Shadow World) linked with Speed 2; Limited (Must Begin and Exit via Naturally-Cast Shadows) (3 Points)Soul-draw: Cumulative Affliction 6 (Resisted and Overcome by Will; Dazed, Disabled, Incapacitated), linked to Regeneration 6, Persistent, Source (Soul) (24 Points)Advantages: Attractive 2*, Benefit (Wealthy 1), Daze (Intimidation), Defensive Attack, Diehard, Equipment 2 (Car, plus 2 points worth of Equipment), Fascinate (Persuasion)*, Hide in Plain Sight**, Improved Initiative, Power Attack. (6 Points)

*Using Allure, **Using Allure Reversed

Skills: Athletics 2 (+6), Close Combat (Unarmed) 2 (+5), Deception 2 (+8/+13*), Insight 2 (+4), Intimidation 2 (+8), Perception 2 (+4), Persuasion 2 (+8/+13*), Sleight of Hand 2 (+2), Stealth 2 (+2/+10**), Vehicles 2 (+2). (10 Points);

*Using Allure, **Using Allure Reversed

Offense: Initiative +4; Demonic Claws +7 (Close Damage 5, Penetrating 5); Unarmed +5 (Close Damage 4); Hellfire — (Reaction Damage 2, Penetrating); Soul-draw — (Cumulative Affliction 6)

Defense: Dodge +4, Parry +4, Fortitude +7, Toughness +8, Will +4 (10 Points)

Power Point Totals: Attributes 26 + Powers 68 + Advantages 6 + Skills 10 + Defenses 10 = 120

Complications: Motivation—Freedom: Anders wants to be free to do whatever the hell he feels like doing (or who; mostly this comes down to capitulating to his libido and demonic drives without having to look over his shoulder every five seconds), but like all lone demons, the laws of the “Accords” mean that any supernatural type on their own is more-or-less free game as a target for the others. Anders, however, hasn’t really sought out a pack, instead relying on himself and avoiding others as much as possible, and making the most of the three nights of the full moon—when the other supernaturals gather to renew their bonds—to enjoy unfettered access to whatever (or whoever) catches his attention. Lust Demon: Anders is a demon, which means he has no soul of his own, and feeds on the souls of others to stay alive and to keep his abilities in play, some of which are much harder to use if he hasn’t “eaten” enough. His lack of soul also means consecrated ground is impenetrable to him, and magic keyed to affecting demons is a particular weakness of his—one of the many reasons demons in general (and Anders in specific) has no love for the wizards of the world. Packless: Anders has no pack, which makes him a target of other demons as well as any other supernatural types, and most packs wouldn’t accept him anyway—owing to him being gay. While he’s got some not-openly-hostile contacts among the other packless demons out there, he knows he’s not truly safe, even with them.

A Bit More ExplanationMuch like Curtis last week, Anders on his own isn’t as tough as he’d like to maybe pretend to be, though he’s definitely more capable in a fist-fight (or, y’know, flaming demonic claw fight). The hardest bits to figure out were actually his shadow-walking ability and his ability (and need) to draw on souls.

For the shadow-walking, I considered Teleport, but I’ve always written Anders’s treks through the shadowy dimension as more like a compressed, faster-journey rather than something instant, and so I decided to make it a Movement power instead, to a single dimension—which also allowed for other demons to be there, as they are on a few occasions in the books—and then gave him a Speed boost while he’s there (which would stack with his other Speed, so he can move around even faster when he’s traveling through the shadow-walk to get from point A to point B). His ingress and egress points have to be through naturally-cast shadows, of course, as it is in the book.

For his soul-draw, I went with an Affliction, which means technically it can be weaponized in the rules as written, but that’s never really how it worked in the book, though he does describe it as dangerous quite a few times were he to over-use it on one person, so I’m okay with it being an attack. I also tied it to a regeneration ability because more than once in the story he notes he’ll heal up fast once he’s had a chance to nab some soul.

Then, when it came time to consider his ability to shift his form—what he calls his allure—I realized Morph was already laid out pretty perfectly as an ability in Mutants & Masterminds, especially with the “Limited” flaw, to align to Anders’s limited ability to shapeshift: he can adjust his appearance only insofar as he can adjust his appearance to be most appealing to an individual he chooses. Adding in the two ranks of Attractive and Fascinate (Persuasion) flavoured it just right to represent how Anders can capture the attention of men who are attracted to other men, and then manipulate (read: seduce) them for ease of access to the soul he needs. Anders also “reverses” his Allure a few times to avoid notice, which I decided to make part of an array of the Allure ability—because he can’t be both attractive and unnoticed at the same time—and so used the same point to make him hard to notice, which he uses a few times in the books to sneak around, and given it’s about an aura of “not interesting to look at,” I added in the flaw of it not working against technology. Then, given it was also about shapeshifting, I added one more option to the array: his demonic claws, which he doesn’t use super-often, but it’d be hard to imagine him being “not interesting to look at” while having sharp demonic claws, nor would it be particularly alluring or appealing (well, okay, I can hear some of you warming up your keyboards to argue that, but work with me here).

Like Curtis, I wanted to note how some of Anders’s powers are tiring—adding the “Fades” flaw to his Hellfire—but I didn’t go as far as I did with Curtis because Anders doesn’t struggle with it as much in the books, other than the references to him needing to recover some soul when he’s been injured or he’s had a particularly long string of using his abilities, so I left it mostly as a Complication. Similarly, this would be a version of a packless demon that’s also a player character—like orphan wizards, I’d probably write up random packless demons as PL 6 or so.

And, just like Curtis, once Anders forms a triad, he’ll definitely get an upgrade from PL 8.

This leaves only Luc to make his pre-traid appearance—and then I’ll need to wrap my head around how covens, coteries, and packs usually work from a game mechanics point of view—and if you have any thoughts so far, I’d love to hear them.

And as always, if you’ve got nerdy news to share, drop it in the comments!

February 18, 2025

Tabletop Tuesday — Triad Blood and Mutants & Masterminds: Curtis Baird

It’s Tuesday, so as I’m trying to do on a weekly basis, I thought I’d pop round here for a game-related post, and this time I’m going to bite off a beginning chunk of something that will likely take me weeks and weeks to cover in any sort of complete sense, but has been nibbling at the back of my mind for ages. Specifically: a tabletop role-playing-game set in the Triad world.

I’ve scribbled ideas for card games before, and I’ve not abandoned that idea. I also did a really watered down in-person one-page-RPG version on a post-card for Romancing the Capital once, called Covens of the Capital. Clearly, gamifying the Triad Blood series isn’t letting go, and… it hit me.

There’s already a really versatile, fun game system out there that totally has everything necessary to play in the Triad Blood series world—Green Ronin’s Mutants & Masterminds.

Where it all began…

Where it all began…If you’ve not played Mutants & Masterminds before, I’ve talked about it a lot, so feel free to check out the various discussions thereof, but the short version is it’s a superhero game with an amazingly open character generation process (seriously, I’ve yet to run into someone’s idea that I couldn’t turn into game stats), which might make you blink a bit because it’s not like the Triad Blood series is, y’know, superheroic.

But it is—if you file off the serial numbers—about people with powers. It’s just that those powers come from being a vampire, a demon, or a wizard. (Or werewolves, druids, spirit-speakers… you get the idea.) The flexibility of Mutants & Masterminds is the win, here: frankly, you can use it for any setting that involves using some sort of powers to overcome those opposing the players. Sure, I’ll have to come up with some setting-appropriate meta-rules (like how “residency” works, for one), but to start with, I thought I’d write up the three main characters one-by-one—and specifically, how they were when they all met in the short story Three, their first appearance.

Which is to say, when they were all alone, and doing their best to survive that way. So, if you’re curious how Curtis Baird, Orphan Wizard would play at a tabletop session? Here he is…

Curtis Baird, Orphan Wizard (PL 8) Artwork by the awesome Micah.

Artwork by the awesome Micah.Cis Male, 21 years old, Height 1.7m, Weight 69kg, Dark brown eyes, Dark brown hair

Group Affiliation: None, Base of Operations: Ottawa

Abilities: Str 0, Sta 1, Agi 1, Dex 1, Fgt 0, Int 4, Awe 4, Pre 2 (26 points)

Powers:

Magic: Array (16 Points, plus 2 points of Alternate Effects)Binding Spell “Necto”: Ranged Affliction 8 (Resisted and Overcome by Will; Hindered and Vulnerable, Defenseless and Immobile), Extra Condition, Limited Degree. Healing Spell “Curatio”: Healing 5, Restorative, Stabilize (1 point)Illusion Spell “Ostendo”: Visual Illusion 8 (1 point)Sorcery: Variable 5 (Elemental), Fades (30 points), for example:Dark Skies: Environment 8, Cold, Visibility 2 (Uses 24 of 25 available points)Wind Blast: Ranged Damage 8, Accurate 4, Indirect 4 (Uses 24 of 25 available points)Enchanted Glasses: Senses 3 (Mystic Awareness, Analytical, Flaws: Concentration, Removable, Tiring) (1 point)Enchanted Carnelian: Enhanced Advantages: Fascinate (Persuasion), Very Attractive, Removable (2 points)Advantages: Artificer, Benefit (Wealth 1), Equipment 2 (Car, Headquarters—Baird House (Library, Living Space)), Fascinate (Persuasion), Languages 2 (Native English, plus French, German, and Latin), Ritualist, Very Attractive. (7 Points)

Skills: Athletics 2 (+2), Deception 2 (+4), Expertise: Linguistics 8 (+12), Expertise: Magic 8 (+12), Insight 4 (+8), Perception 4 (+8), Persuasion 4 (+6) (+11 to those who find men attractive while wearing the Enchanted Carnelian), Stealth 2 (+3), Vehicles 2 (+3) (16 Points)

Offense: Initiative +1; Binding Spell “Necto” — (Perception, Affliction 8); Wind Blast +8 (Ranged Damage 8); Unarmed +0 (Close Damage 0)

Defense: Dodge 5, Parry 5, Fortitude 4, Toughness 1, Will 12 (20 Points)

Power Point Totals: Attributes 26 + Powers 51 + Advantages 7 + Skills 16 + Defenses 20 = 120

Complications: Motivation—Freedom: Curtis Baird wants to be free to use his magic without bowing to the Families—or anyone else, for that matter. The laws of the “Accords,” however, mean that any supernatural type on their own is more-or-less free game as a target for the others, so Curtis is trying to find two other individuals to create a coven of his own. Quirk: Curtis’s magic and sorcery is strongest when tied to the element of air, which requires him to speak to use his magic effectively. He also describes his magic as “wanting out” which means sometimes, if he’s not careful to control it, Curtis’s magic will activate on its own, especially when he curses, or uses new words for the first time aloud. Orphan: Since Curtis hasn’t bound himself to two other wizards and created a coven, he’s not only on his own, he’s garnered the attention of the Families, who’ve already killed his parents as a “warning” not to use magic without their approval. Curtis has to hide to make sure they don’t catch him using magic at all, let alone to try and find two others who might be willing to defy the Families and join him to create a viable coven.

A Bit More ExplanationIf you’re familiar with Mutants & Masterminds, you’ll see Curtis alone isn’t actually particularly tough. In fact, at this point in his life, he’s still figuring it all out, reading anything and everything he can find on magic, and working his spells in secret. He has made his enchanted glasses that let him see if other supernaturals are around—though as in the story, I added “Concentration” to them as a flaw as well as “Tiring” to represent them giving him headaches if he tries to use them too much. Similarly, Curtis can fling around some impressive sorcery—what he calls the more “shot-gun” approach to magic—but that well runs dry pretty quick, which I represented by giving the incredibly flexible Sorcery the “Fades” flaw.

Those represent the limits as I wrote him: he’s capable of quite a bit, but he also gets tired when he pushes himself—especially at the start, when he’s on his own and hasn’t bound himself to any others to create a coven.

That also plays out in his Complications, where I tucked orphan as a Complication, rather than a fully-fledged game mechanic, or at least, partially so. His orphan status is also why I used PL 8 for this version of Curtis. And were I running the game as a Gamemaster, Curtis would only be PL 8 because he’s definitely a player character—I think I’d stat out most random Orphans as PL 6 opponents—but you get the idea. Once Curtis meets Luc and Anders and they create their bond?

Well. He won’t be PL 8 at that point.

Let me know if you’d like to see more along these lines. I’m for sure intending to at least drop Luc and Anders into the mix—both before and after their form their Triad—but if people like the idea of this, I’m happy to keep going. And as always, if you’ve got nerdy news to share, drop it in the comments!

February 11, 2025

Tabletop Tuesday — Frosthaven

Since I chatted about Gloomhaven: Buttons & Bugs a couple of weeks ago, I’ve had thoughts about Frosthaven in my head. When we first got Frosthaven, we were super excited (seriously, even just opening the box had me giddy because of how Frosthaven, very unlike Gloomhaven, was able to go back into the box!), and I’ve mentioned previously how I struggle with Legacy games because, y’know, they make you change the game itself—stickers!—but I was happy I bought the reusable stickers for Frosthaven rather than the permanent ones. When Frosthaven arrived, I was so excited! And myself, my husband, and the two players we’ve played all the other Gloomhaven games with gathered and began our trek to the frozen wilds of this world to play this legacy game, which was the latest in the series of games we’d (mostly) really enjoyed (except for Forgotten Circles, which was so bad).

Frozen!

Okay, for the most part, now we’ve played three years worth of in-game timeline (and have been playing Frosthaven itself in the real-world for going on two years) the answer to “What do you think of Frosthaven?” is… it’s complicated.

Let me go back to our experience with what we disliked most about Forgotten Circles (which was a lot): the complicated scenarios that had you flipping back and forth through a book while playing, pausing to decode things mid-game (which ground everything to a halt), and a new character (which unfortunately I was playing) that was basically the antithesis of “fun” because every other scenario (or more) was designed with having stuff that only that character could even possibly attempt to do, which railroaded my playing experience down to “I have to be the move from this pressure plate to the next one rather than choosing to do anything else, or we lose.” It’s quite telling that in what they called the “second printing” they changed almost every single card for that character—I don’t call that a second printing, I call that a second edition.

Frosthaven is not as bad as all that. But it also hasn’t been as fun as Gloomhaven was. It’s in the middle.

The starting characters were all fun to play, and there hasn’t been one yet we haven’t enjoying playing (even the ones we’ve unlocked, although more on that in a moment). Each character is interesting, and the perk system has been adjusted slightly—there are more ways to gain the checkmarks you need (the battle goal draw deck is much larger, offering you way more challenges to play your character a certain way to earn those checkmarks and tweak your battle deck)—but there’s also “masteries” (which for me fall under the ‘caveat’ category below).

The scenarios do fall somewhere between Gloomhaven (where they were mostly “defeat all the enemies” with a smaller percentage of “here’s a nifty mechanic to apply to the game that changes the goal to something more than defeat all the enemies”) and Forgotten Circles (where it felt like every single scenario was awash in, “okay, so here’s all the rules we’re changing for this particular scenario, try to keep it in your head while you play.”) So, while we were hoping for a more Gloomhaven-like experience with scenarios, it’s more like a third of them? To the point where when it’s time to choose which scenario we want to play next, over the last two years we’ve gotten into a bit of a “brace yourselves” feeling when we see we’ve run out of 1- or 2- complexity options, and it’s time to crack a scenario that’s listed as complexity level 3. Oddly, though, now and then some of those higher-complexity ranked scenarios just… aren’t difficult. But that’s to be expected with four players bringing four different character skillsets to a given game. There are combos that just work for some scenarios. So, overall, the scenarios are okay. We aren’t grinding our teeth through them like we did with Forgotten Circles, but we’re not having as much fun as we had with Gloomhaven where I didn’t have to explain winning conditions at the start of scenarios very often.

One other major update we all like is the loot deck. Instead of just picking up coins when enemies fall, you pick up a loot token and draw from a loot deck which offers coins, yes, but also potentially metal, wood, hide, six different types of plants, or a random item (each scenario has its own combination thereof). Especially early on, when your characters need to craft equipment, those crafting supplies are important (but more on crafting later). It’s definitely more fun than coins, though, is what I’m saying.

The difficulty level feels like it spiked, too, though that could also be a function of not having access to the same solid levels of gear you have in the first game—that aforementioned crafting mechanic, rather than just flat-out buying equipment—and the scenarios having more complexity than “defeat the enemies” far more often. Especially when there’s a new (and therefore lower-level) character in a group with longer-played characters, we’ve found ourselves playing on “Easy” a lot more often than we did in Gloomhaven—and some of those issues are still there for four player games where bad enemy actions drawn on round 1 are just beyond punishing (one player getting pummelled by a half-dozen or more attacks before they even get to act, for example). Now, more difficult isn’t the end of the world, and we haven’t lost a tonne of scenarios, so it’s been okay—but as I said, we’ve definitely lowered our threshold for dropping to “Easy.”

Speaking of easy, I love the division between the Scenario Guide and the Section Book (which is where blocks of unlocked text or secondary locations in scenarios are kept)—huge improvement over Forgotten Circles. You do end up flipping through the Section Book multiple times, but the original scenario remains open the entire time, which makes all the difference in the world, and as yet there have been zero “now stop playing and decode this message” incidents, which huzzah.

Also, Enhancement is really improved, using shaped dots on the cards so when you apply (in my case, reusable) stickers, there’s some sense to what can be modified how, which allows for much more enhancment options (since some cards will only let you add a +1 on a basic symbol, say, but other symbols will let you add +1s, elements, or statuses). But—once again—more on the reusable stickers below.

The Caveats (and there are quite a few)I mentioned that we’ve enjoyed the characters we’ve played and unlocked, and that’s true, but after two years of playing, we’ve still got five characters to unlock. Gloomhaven was far, far more streamlined in giving you new character options, and it’s frustrating to see those boxes still unopened. We know part of that is likely because we’ve been avoiding the higher complexity scenarios when we’re just not up for it Unlike Gloomhaven, you unlock characters in Frosthaven not when you achieve your character life goals, but… randomly at other times. Sometimes it’s upgrading or building a new location in Frosthaven, sometimes it’s at the end of a particular scenario. But there’s no clues to it, so our experience is possible: you can play, and play, and play… and be unlucky enough not to crack open new characters, even as you’re building up your version of Frosthaven and progressing your way through the game.

Also? Masteries. I loathe them. Frosthaven already has multiple ways that challenge your characters during scenarios, one being the battle goal deck, and another one is introduced once you build a particular building that creates an extra condition during each scenario, which I won’t explain because it’s a spoiler, but suffice it to say as you progress, you’ll end up with even the most basic scenario potentially getting quite a bit more difficult because of a drawn card. On each individual character sheet, however, there are also two “masteries.” If you complete a mastery during a scenario, you get a perk. Which sounds great, except the “masteries” aren’t. They’re not about mastering your abilities in a way that makes you more effective or useful to the party, they’re about using your cards in a specific way—one almost never effective or useful for the scenario goal—that leads to a frustrating experience for everyone else (or you, if you’re getting close and then someone else messes it up for you unknowingly). One of our group really likes the masteries, so your mileage may vary, but in the starter-class Geminate, for example, one of the masteries was to “swap forms” every single turn, and that led to three scenarios in a row of utter frustration for the rest of us while the Geminate’s turn seemed to consistently amount to “I move here, and swap forms, that’s it, that’s all I can do!” while we all got pummelled by the monsters. If the “masteries” were more consistently (or even often) something that helped the party, rather than making one player make bizarre choices, it might have been more fun, but for me, they quickly became something I ignored and hoped the other players would ignore, too.

Similarly: potions and crafting were hugely frustrating for the first year or so we played. Adding in a crafting mechanic was an interesting idea, but it had two problems we bumped into. One: there are only two of every crafted item card, which means for four players, we somehow run out of things we’re making out of raw materials we’re collecting. Make it make sense, please, that we can only craft two plain wooden shields when we’ve got the wood and the time? I understand the actual real-world reason—it would double the number of cards—but in-game it’s just bizarre, and especially when you start unlocking potion recipes with the herbs you gather and everyone wants a healing potion but you’ve only got the ability to brew two because… uh… um. Reasons.

Speaking of potions, that was the single most frustrating part of the crafting experience for us in the early game. We unlocked crappy potions first. Truly. It was so frustrating to go from a game where you could buy a healing potion for everyone to a game where we couldn’t even brew up one of the two we’d get access to—eventually. This is just crap luck, to be clear: the loot cards we drew gave us certain herbs, and we were unlocking new potions as soon as we were able on the little potion chart, but it took us ages to finally unlock some of the more basic potions just as a matter of poor luck, and those early games had a layer of unnecessary frustration because of it. Or, put another way, it wasn’t fun to unlock potions because we kept getting potions none of us wanted—we’d use them, grudgingly, but they weren’t what we were hoping for, and the grind to get enough ingredients to “try again” felt entirely like that: a grind.

And, speaking of grind—there’s the post-scenario “Outpost phase.” This is meant to be the “you get back to Frosthaven, what happens?” and while it’s not necessarily a bad thing—there are outpost event cards—sometimes Frosthaven gets attacked and it turns our you’re not done playing for the night, as there’s more card-flipping and a battle and decisions to make rather than a quick post-scenario “okay, let’s stock our loot, craft and buy things, and get ready for the next session.” We ended up “fixing” this (that’s over-stating) by just skipping it once until our next session, when we played it out. We do the Outpost Phase first, then head off to our Scenario, then stop again. So, we’re kind of doing “the last half of the previous session, then the first half of this one” every time we play, but it works for us and doesn’t feel like tacked on homework after a session.

Finally, the reusable stickers, which I bought because I wanted to be able to return the game back to its unplayed form to pass it forward to someone else, or just to start over completely. For whatever reason, in the pack of reusable stickers, there’s everything except the stickers you place in the rulebook, which defeats the entire purpose of the reusable stickers: you can’t actually “reset” the game by removing all the stickers, because the rulebook will have all the stickers you need to add throughout gameplay, and the only option for those are the permanent stickers that came with the game. Annoying.

But Are you Enjoying It?We’re still playing it, so yes.

I know that list above seemed very heavy on the frustrations—and they did frustrate us—but some of those have faded (we’ve now unlocked a wide range of potions, figured out how to home-rule the Outpost phase so it doesn’t feel like post-game homework, and most of us ignore masteries). The still-locked new characters is still annoying, but we’ve replayed some and also used some of the original Gloomhaven characters (for which there are also updated character sheets for using them in Frosthaven, which is nice).

We’re enjoying it enough. But unlike the original Gloomhaven, we also take occasional weekly breaks on Tuesday Gaming Night when we’re not feeling up to it—we’ve played some other board games, some Pathfinder, I also have my Star Trek Adventures groups—and then we go back to Frosthaven again after a week off.

February 4, 2025

Tabletop Tuesday — The Hourglass Sector

Hello! It’s Tuesday, which for me means I’ve got nerdy gamer thoughts on the brain, and today I’m going to delve into some Tabletop Role Playing Game thoughts—this time for Star Trek Adventures. I’ve talked about Star Trek Adventures a few times before—how much I love the Support Crew mechanic, and how the game has a supplement designed for larger-scale war, and how great the 1st Edition Tricorder Boxed set is. While Star Trek Adventures has moved on to a second edition—I’ve got the books, but have only cracked and perused them—as right now both my groups are happily in the groove with 1st Edition, so I’m still using those books. Which brings me to the results of a day where I decided to sit down with the random charts included in the 1st Edition Core Rulebook and the Shackleton Expanse Campaign Guide, and detail a sector.

Narendra Station, Ancient Technology, and Klingons, oh my! See what I mean about the bottleneck by Narendra Station?

See what I mean about the bottleneck by Narendra Station?One of my two ongoing Star Trek Adventures games is set in Beta Quadrant Federation space, aboard the USS Bellerophon, an Intrepid-class starship, working out of Narendra Station and delving into the Shackleton Expanse, a vast area of space behind an odd, nebula-like barrier known as “the Endurance Divide” and inside of which are disturbances in subspace, odd dimensional effects, and hints of an ancient race with incredible technology. About one in three of our adventures have come pretty much out of the aforementioned Shackleton Expanse Campaign Guide, which has a campaign of ten TNG-era episodes that’ll explore the Expanse.

In between, I’ve been writing my own adventures, sometimes drawing on the “Mission Briefs” included in the Campaign Guide (which are great, one-page inspiration pages with ideas for episodes to explore the setting further). It took a while for us to really get to visit Narendra Station (which is maybe worth a blog post of its own about the Shackleton Expanse campaign, come to think of it) but as my group approaches the mid-point of 2372, things are going south with the Klingons, and on the maps of Federation Space in the Beta Quadrant, something becomes clear: without permission from the Klingons to move through their space, Federation territory in the Beta Quadrant is quite cut off from the greater Federation as a whole.

And even worse? There’s a bottleneck right near Narendra Station that could make that bad situation even worse, splitting Beta Quadrant Federation space into two halves. Which would definitely be something an enemy would like to do. As the Gamemaster, I can’t help but look forward to making this area of space important during the upcoming Klingon-Federation War—and I decided that bottleneck created a nickname for the sector among the Starfleet crews: “the Hourglass Sector.”

Just Add DiceThe Star Trek Adventures’ Shackleton Expanse Campaign Guide has a chapter devoted to random sector generation, with the idea that sectors are twenty-light-year cubes, and one of the first things you determine is how many systems “of note” are included in a sector. There are actually hundreds of stars and systems in any given sector, but only so many have something particularly interesting, basically. I threw a dice and learned there were nine star systems of note in that little square up there in the centre I’m calling the Hourglass Sector. There are only two noted locations on the map: the star system that includes Narendra Station, and Klach D’Kel Brackt, a Klingon location of a famous battle.

So I’d be needing seven more star systems. As a prompt for game-masters, the charts in the guide help you roll up stars (determining their spectral class, spectral-subclass, and luminosity)—so three dice later, for example, you’ll know your first star is a G4IV—A G-type (a yellow star) mid-way through the temperature range, with a luminosity of IV (making it a sub-giant)—or, something like that. I’m not a scientist, and this is Star Trek, so all I need is the dialog to sound right when my science officer asks me details about the star system.

Once you know your primary star, you need to decide if you’re looking at a multiple system (binary or more) and while the charts offers an easy “choose or maybe roll for it” I made up my own process using the first edition “challenge dice” (which are six-sided dice with two blank sides, two sides with Starfleet “deltas”, a side with a 1 and a side with a 2) where I count the number showing after rolling two dice, which gave me results consistent with the current theory that a third of star systems out there are multiple, given nine of the thirty-six results will be a 2 (a binary star system), two of the results will be a 3 (a trinary star system), and one result will be a 4 (a quaternary star system). Otherwise, it’s a single-star system (twenty-four results out of thirty-six). Oh, and if I roll a 2 and one of those “delta”s, I decide it’s a rare binary with planets following an S-type orbit—meaning rather than the planets orbiting both stars at once, there are planets orbiting each star, separately, as those stars swing around each other.

There are more charts for planets, randomly determining how many planets the system of note has (it’ll always have at least one, given it’s, y’know, a system of note, but there are some nods to science in terms of nudging down how many planets binary star systems have, or depending on the age of the star, but—again—this is Star Trek so we’re only following science so far). Once you’ve rolled up your planets determining their types (in Star Trek terms, Class M and the like)—which includes figuring out which planet in particular is “of note” and even has a chart to roll on to explain why it’s interesting, though it doesn’t have a large number of options and you’d likely have more luck on that front with the Captain’s Log charts, or my trusty favourite: Deck of Worlds—you carry on with more dice rolls to assign moons.

Then, if you’re wanting to get specific with your sector, you can roll d20s again to create X, Y (and even Z) co-ordinates inside your twenty-by-twenty light-year sector cube, and… ta-da!

Welcome to the Hourglass Sector

So, a bunch of dice-rolls later—and then some zipping about on Memory Alpha—and what did I end up with? A much better picture of the Hourglass Sector for my campaign, and more than a few ideas for making Narendra Station take centre stage, a better idea of nearby Klingon space, and systems I can use later when I play out the Klingon-Federation War of 2372-2373.

Hegh Hur’q—Binary Star System, G8V and M2III, which orbit in a close pairing and share a single system of six planets and an asteroid belt. The system name translates roughly into “Outsider’s Death,” in a reference to the Hur’q artefacts discovered on the fourth planet, which is M Class and contains remnants of the Hur’q invasion of Klingon Space, which is good for an archeological story or two.

chal toj—A K7VI star with three planets. The system’s name is a reference to the extremely volatile weather found on the third planet, and roughly translates to “deceptive sky.” Said planet, which is Class M also has two Class D (barren, rocky) outer moonlets but one larger Class M Habitable moon, making it a two-for-one system of interest, and maybe somewhere useful for a “crash-landing” and “survival” type story during war-time.

Yattho—Binary Stars System, M6V and M1VI, which orbit in a close pairing and share a single system of four planets, the fourth of which is a low-G inhabited planet, the Yattho homeworld. I’ve already introduced the Yattho in my campaign (you can read about them on Continuing Mission, in fact), based off a throwaway line from a Star Trek Voyager episode, but when the roll came up “peaceful technological inhabitants” I decided this was where they lived. In Klingon records, a prefix of “jegh” denotes the Yattho’s jeghpu’wI’ status (“a conquered people”).

Hafgufa—A single K6V star with one large ocean planet. When the prompt came up “exceedingly dangerous animal or plant life” I went with aquatic animal life given it’s a Class O planet, rolled a d20 to see how much landmass there was and rolled a 1, and thus decided only 1% of the planet’s surface is terrestrial, entirely made up of volcanic high islands. The sheer variety of deadly ocean creatures discovered by the crew of the USS Bjarni, the first starship to survey the planet in 2293, had them naming the star system after a Norse mythological ocean beast.

Jökull—A single M5IV star with one Class P (glacial) planet. Tribes of primitive inhabitants were discovered during the planet’s initial survey by the USS Bjarni in 2294, but as the population was pre-warp, and the climate difficult, they limited their findings to orbital scans. Starfleet sent an embedded anthropological team of Andorians for covert duckblind observation of the locals in the 2330s. The largest group of local humanoids refer to their species as the Amyra, which roughly translates to “People of the Ice,” and the planet itself simply as Yra (“Ice”). The planet has only 13% terrestrial surface area, though the Amyra population also inhabits various locations on and in the glacial ice, much like Andorians do. When I rolled up this right after Hafgufa and got a result of a glacial planet with pre-warp and primitive—and also violent—natives, I decided to continue with the USS Bjarni and its Norse naming theme.

Arev-Vokau—Binary Stars Arev (M1V) and a Brown Dwarf (Vokau), orbiting widely; this distance allows both stars their own planetary systems in S-type orbits. The M1V star, Arev, has seven planets, the Brown Dwarf, Vokau, has one. Named by a Vulcan astronomer, the name translates roughly to “The Desert Wind’s Memory,” something I decided when I kept rolling desert planets for Arev’s inner planets, and decided the planet of note, Arev IV, was mineral rich, including deposits of dilithium, but has near-constant sandstorms with kelbonite and fistrium particulates, which limit or prohibit transporter use on a regular basis (the prompt I rolled). As a Class K world, the planet could become habitable with terraforming, and I’ve already introduced a group of miners in my campaign. This could be somewhere for them to go, and, of course, get in trouble and need aid.

G’Shalia—A single G4IV star with two planets and an asteroid belt, the prompt I got for the third planet was it was Class M, but had “off-world visitors.” I decided that since it was outside of both Federation and Klingon space, that it belongs to the Nyberrite Alliance, a group mentioned once in passing by Worf on DS9, that I’ve been fleshing out for my campaign. That makes G’Shalia somewhere that could be—in a pinch—a place to fall back to, but the Nyberrite Alliance maintain a politically neutral stance, which makes heading there potentially a problem during times of conflict with the Klingon Empire.

And there you have it. Seven star systems all rolled up and suddenly the Hourglass Sector feels more alive—including multiple worlds with potentially tactically important qualities, different political situations, and different allegiances to handle during the upcoming Klingon-Federation War. All with rolls of some dice.

Have you got any tools you use to world-build? Hit me up with them.

January 28, 2025

Tabletop Tuesday — Gloomhaven: Buttons & Bugs

Hey all! It’s Tuesday, and I’ve got one more gaming gift from under the tree from Christmas to chat about today. It’s the latest in the Gloomhaven series, which we’ve (mostly) loved, with only a single real caveat—looking at you, first edition Forgotten Circles—and I’m thinking I might do an update on how we’re feeling about Frosthaven next week (spoiler: it’s… a mixed experience for us). Jaws of the Lion, which was designed as a “starter” version of Gloomhaven (but came out after Gloomhaven) was a great addition and one I whole-heartedly suggest you start with if you’re thinking of hopping on the Gloomhaven train, and honestly these games are the closest I’ve really found to an RPG-like/lite that plays out on a tabletop board game but still scratches most of the RPG itches, but now we’ve got a single player option.

It’s All You, Baby He’s riding a button palanquin!

He’s riding a button palanquin!Buttons & Bugs is a one-player, portable* boxed Gloomhaven experience with a campaign you can play with one of the six original character types from Gloomhaven itself, and the core conceit is you’ve been shrunk and you’re trying to make your way across a long-abandoned inn to get to someone who can help you. Yep. You’re literally bug-sized (and this is in a game where sentient bug colonies form collective consciousnesses, so it’s probably serious business!)

Quite a bit of the game follows the basic rules of the games that came before it: each turn you pick two cards, do the top action of one and the bottom action of the other (including adjusting them to basic moves and attacks if you don’t want to do what’s on the card), but the first “streamlining” to make this game box-sized is you only have four cards to work with for each character (though they get substituted for “better” cards as you level up), and there’s a different mechanic at play with them. They all start with their “A” sides face-up, and when you use a card with an “A” side on your turn, those “A” side cards are flipped to their “B” sides and returned to your hand instead of being discarded, but when you use “B” side cards, those are discarded like in regular Gloomhaven. That took a bit to get used to—it’s not intuitive, especially if you’ve played the other Gloomhaven games—and how elements are handled is also different, but it’s all in the name of streamlining.

The other difference is the relegation of a lot of the randomness of Gloomhaven (the battle decks, what enemy actions will be) has been shifted from decks—because that’s bulky—to a single dice roll. The dice has two plus sides, two minus sides, and to zero sides. Functionally, this changes enemies the most: they now only have three possible actions in a given turn: a plus, a zero, and a minus, to match the dice (elite enemies, instead of being generally tougher, instead act on two of those three possible actions every turn). The dice also replaces everyone’s battle decks, instead moving you down a track with each roll choosing from three possible alternatives each round. I should note I quite like this, as this version of a battle deck has the added advantage of you knowing exactly when that dice roll means you’ve got access to your 1-in-3 chance of drawing your miss or your critical hit, so it’s an extra level of planning you can work with. Advantage allows you to roll twice and choosing the best, Disadvantage is rolling twice and taking the worst.

Equipment is handled really cleverly, with strips of text at the bottom and top of every scenario you’ve completed representing loot from said scenario (including adorable things like using a literal button as a shield), and you choose your equipment from everything you’ve got access to during each scenario by tucking it under your character so only the loot text shows.

Elements, which are key for some characters more than others, are a bit fiddlier in this version of the game. You’ve got no chart of elements being infused, waning, or exhausted—instead, if any of your cards in your hand or in play show an element-is-infused icon, you (or an enemy) can use it—once. This is different from regular Gloomhaven for the enemies (in regular game, all enemies of the same type get the benefit of an element if any one of them uses it, but in Buttons & Bugs only one of them does), but plays out the same for a character in the sense of “if an element is there, you can use it up, but it’s gone for the rest of the characters and enemies.” It’s a pretty elegant solution and keeps the flavour.

In fact, most of the mechanics are like that—simplified, but in keeping with the theme and tone of the original game. I’m only a few scenarios in, as is my husband, but so far? Buttons & Bugs is pretty fun.

The CaveatsTo start with, let’s address the asterisk up there when I introduced Buttons & Bugs as portable. Technically, it’s true—to the end of the first scenario. At that point, the rules run out. See, the complete rulebook for Buttons & Bugs is only available online and—this is the part I can’t wrap my head around—there’s no downloadable .pdf version you can print for yourself. It’s online as a website. There are downloadable scenarios in .pdf, and sure, you could use your browser to make a .pdf from the website, but that leads to funky printing results (lines of text can be half on one page and half on the next). It’s a glaring omission.

Next? The difficulty level. Oof. This game is unforgiving, and a great deal of that comes down to having only four cards to work with and needing to balance when you need your character to rest—which costs you a card—and how many enemies are going to pummel you in the meanwhile. It took me three tries to succeed at the first scenario because I just kept rolling poorly for myself and well for the enemies, and that’s unfortunate. Then again, Gloomhaven had the same balances issues now and then, too—Oozes, I’m looking at you.

Finally—and I’m aware this is nitpicky—it’s a bit too small. The box being 7.75 cm x 10.5 cm and 7 cm tall makes it portable, but it’s not quite “put it in your pocket” portable so I think I would have preferred a bit more size if that meant I wasn’t trying to move tiny plastic cubes (representing the enemies) on a small hex-grid card map where it’s all to easy to bump or nudge the card or cubes and accidentally move everything. Going somewhat larger would have been appreciated for me and my clumsy/damaged hands.

January 21, 2025

Tabletop Tuesday — 25th Century Games’s Color Field

As I mentioned two weeks ago and last week, this year I backed the kickstarter on a trio of games from 25th Century Games which we’ve since had the opportunity to play a couple of times. They’ve all got something pretty cool going for them—not the least of which being they’ve lived up to their “20-40 minutes” playtime—and while last two weeks we were talking donuts and umbrellas, this week we’re painting an abstract masterpiece. Or, okay, we’re mushing paint around on a canvas.

Turquoise, Coral, Lemon, and Navy Don’t get excited, you will not be mixing coral with lemon to make tangerine.

Don’t get excited, you will not be mixing coral with lemon to make tangerine.The basic concept behind Color Field is pretty simple: you’re an artist, you’re painting an abstract, and you are using four colours to do this: turquoise, coral, lemon, and navy—and you are not mixing them to make any other colours, to be clear. Just blobs of absolutely not light blue, pink, yellow or dark blue, but—I must stress this—turquoise, coral, lemon, and navy. Because we’re artists here.

Okay, but for real, we constantly forgot what the colours were called and it didn’t matter, even though all the cards refer to them by those names. It’s cool.

Each player gets a canvas (which has space for a 2×3 grid of tiles) and already has colours painted all around the edges, and you set up “starting” tiles at random on your canvas, and then you take three rounds drawing tiles from three different stacks (one for each round) while building up your painting. When you choose a tile, you have a choice between three that are face-up on a palette, or a blind draw, and you can swap what you draw with one of the six tiles on your board, and you can place a newly drawn tile in any direction you want, which is the key thing, as you want to match the blobs of up to four colours against as many of the neighbouring tiles and the border of the canvas itself as you can.

You score points for matching edges at the end of each of the three rounds, as well as points for the longest streak of a particular colour, and also there are cards that randomize some of the rules or scoring each game or round for replayability. Between each round, there’s also a bit of a rubber-banding in place—the people with the most points reset more of their board than the people lagging behind as you move to the next round, so they can choose to give themselves got a bit of a head-start or just keep a tile or two that’ll be useful where it is. We found that an extra wrinkle in the strategy that was welcome: getting a lead way out in front isn’t always the best choice for the later game.

There’s also a mechanic called “inspiration” where up to three times in any given game you can spend one of your inspiration tokens to rotate/swap/move some tiles to adjust your painting, but that’s about it. Each turn you’re drawing a tile, swapping it with one on your canvas, and trying to create a better number of matches for higher points (with an eye on any goal cards that’ll adjust what scores better in any given game).

Much like Águeda: City of Umbrellas, this one doesn’t feel as “versus” as a lot of other games, with the exception that everyone is drawing from three face-up tiles, which means sometimes it’s possible the best move for you is to stymy someone else’s tile that would be great for them, but honestly it felt to us like most of the time, you’re trying to do what’s best for your painting, not complicating what another artist is doing with their yellow, say.

Sorry, I mean lemon. Lemon. Ahem.

It’s fun, but of the three games I backed and we’ve played, this one definitely goes longer than the other two in our experience, because tile selection involves a lot of “hrm, what if I put it here, wait, no, if I rotate it and put it here? Oh, no, that’s not quite right… hang on…” time, which is fine, but I can’t imagine anyone actually finishing a game in 20 minutes unless they’ve got some serious mental imaging abilities. Even though you’re literally limited by the number of draws you take each round and are only making a certain number of decisions, 20 minutes seems really, really unlikely to me, especially if you’ve got more than two players.

As with Águeda: City of Umbrellas and Donut Shop, we got the deluxe edition of Color Field, and the only additions there are some complexity-increasing cards, and wooden tokens for the inspiration tracking, both of which are fine. To be honest, we’ve yet to really play with much of the community cards because just rotating the tiles and keeping track of the basics is enough, and those cards do thinks like making one of the four colours “wild” for scoring matches and if I can’t remember it’s lemon instead of yellow, I really don’t trust myself to remember all the lemon blobs are actually whatever colour I want them to be.

January 14, 2025

Tabletop Tuesday — 25th Century Games’s Águeda: City of Umbrellas

As I mentioned last week, this year I backed the kickstarter on a trio of games from 25th Century Games which we’ve since had the opportunity to play a couple of times. They’ve all got something pretty cool going for them—not the least of which being they’ve lived up to their “20-40 minutes” playtime—and while last week we were talking donuts, this week we’re talking umbrellas.

I’m Not Singing Unless There’s Rain Under my umbr-ella ella ella…

Under my umbr-ella ella ella…Águeda: City of Umbrellas has the players in the role of artists, decorating the city in question for the umbrella-themed celebration (with the goal of attracing tourists). Through game-play, you decorate your street (with some input from the managers of the various storefronts), put together a mural, and hang those umbrellas for maximum impact (and tourist dollars). There are six colours of umbrellas (each with a handy pattern in white for those of us with colour issues), little tourist markers (you start with four tourists unlocked and can gain up to three more if you’re careful with your umbrella placement), and there are two randomized elements in the form of tourist tiles and shop cards (the aforementioned “what the store owners want”).

Every turn you decide whether you want only one umbrella (and gain a coin), two umbrellas, or want to spend a coin to gather three umbrellas, but those choices are taken from a market area where the current umbrellas are laid out for sale, and this means you don’t always get your ideal choice, and you’re working with what’s available. Umbrellas are blindly replaced from a bag, and you do have to take at least one umbrella on each of your turns. You’re decorating your street in three rows of umbrellas, and you can only place any umbrellas you picked up in one of your rows on any given turn (if you have extra once that row is full, they get tossed back into the bag).

Particular spaces on the those rows have little paintbrush symbols on them to unlock your street’s mural—you’re aiming to get one umbrella of each colour onto those paintbrush symbols, but that can be impossible if the wrong colours of umbrellas are available on your turn—and freeing up pairs of this six-part mural unlocks extra tourists.

You’re also attempting to make the shop-owners happy (the cards, which explain how points are gained in any particular game, and are different every time, so in one game you might want a balance of two colours, in another game you might want no more than three of a particular colour, and other variations that make each game different).

Once you’ve placed umbrellas, you get to draw a tourist to any of your three rows (up to two tourists can visit a particular row) which is where those random tourist tiles come into play: each tile has two colours of umbrella on them, and you’ll gain a number of points equal to the number of umbrellas matching one or both of those colours, depending on if you send one tourist or two to snap photos. Or, you can take a rest, send all the tourists back to your holding zone, and then adjust the tiles into new positions (which you’ll want to do at the right time to maximize the next tourist visit thereafter…)

Once someone fills in their street with umbrellas, everyone else gets their last turn, points are tallied, and you’ve got a winner. This game felt less competitive than Donut Shop, but there are still moments where you realize the smartest move for you is to stop someone else from getting a particular umbrella colour, but for the most part, you’re more likely going to be concerned with what’s the best move for you. If the above rules sound complicated, they’re not: you basically do only four things every turn: pick umbrella(s), place umbrella(s), update the murals if you covered a paintbrush symbol (and maybe unlock a tourist), and then either attract a tourist (or two) to a row, or take a break and reset the tourists and move the tourist tiles. Once you’ve got the flow down, it goes quickly.

It reminded me of an Azul with more complexity from the point of view of how points are scored.

As with Donut Shop, this was the deluxe edition, and I’ll repeat: sometimes, less is more. I’ll never consider metal coins as an upgrade (we play on a glass dining table, and it’s (a) loud, and (b) makes us nervous we’re going to scratch the surface) and honestly I’d rather just use little cardboard tokens. We also found the plastic umbrella tokens to be a bit fiddly—they’re shaped like umbrellas looking down from above, but they’re not flat, and quite easy to bump or knock—so this one needs you to pay attention while you’re playing.

January 7, 2025

Tabletop Tuesday — 25th Century Games’s Donut Shop

Christmas at our house tends to mean board games, and while we didn’t do nearly any gift-purchasing or gift-giving this year (everyone wasn’t really feeling it, and we decided to do destress the holidays as much as possible), we did pick up a few board games for each other. And this included a trio of kickstarted games I backed from 25th Century Games which we’ve since had the opportunity to play a couple of times, and they’ve all got something pretty cool going for them—not the least of which being they’ve lived up to their “20-40 minutes” playtime.

Okay But Who Thinks Sprinkles Are Upgrades? Seriously, who thinks sprinkles make donuts better?

Seriously, who thinks sprinkles make donuts better?First up is Donut Shop. This one is a tile-placement game with a couple of little twists, but themed around running a donut shop and working the counter. There are five kinds of donuts: Boston Cremes, Custard Filled, Honey Crullers, and two glazed donuts (one blue, one white), but for the most part we found ourselves just referring to them by colour: “blue, white, yellow, brown, and… cruller.” Each tile is made up of a combination of four of those five types of donuts in a 2×2 arrangement on trays, and some of those tiles also have piles of donut-holes in one of the four positions as a wild card. The game starts with a plus-shaped starting tile (the equivalent of five tiles, three horizontal wide and tall). When you place a tile, you count up how many donuts are orthogonally connected of one kind (including donut hole wild cards) and gain 5 cents per donut sold.

So, y’know, clearly this is what, 1940s-1950s-ish?

Anyway! Once you’ve placed your first tile and collected your nickels, you’ll draw a replacement tile (either one of the two face-up, so you can plan your next move, or one that’s face down and random) alongside an order card. The different types of donuts are all represented on the order cards (one type of donut per card), along with potential bonuses like a cup of coffee, or extra money if the donut has sprinkles (ew), and the use of these order cards, alongside different sizes of donut “to-go” order boxes—and this is where the strategy really starts to be added to the game.

You pack up “to go” donut orders by covering the donuts on the tiles with the boxes: a small box is just four donuts (2×2), but there’s also 6-packs (2×3), 8-packs (2×4), 9-packs (3×3) and the largest box holds a dozen (3×4). To place a box tile overtop of the donuts on the ever-expanding placed tiles, you have to have cards that match every type of donut you’ll be covering with the box tile, but if you do, you can box up an order at the end of each of your turns once you’ve got order cards to work with. The larger the box, the more the price, but by covering the tiles, you’re also blocking areas of the ever-growing game board, as those donuts are “gone” and now can’t be counted during the placement of a tile.

And there are various bonuses on the order cards, like I said (including—for some unholy reason—bonus cash if you’ve got sprinkle-covered-donuts), but that’s the basics, and since you have one tile to play every turn, and only really have those order cards to work with for planning—and if there’s a face-up order card you really want, you’ll be taking a random face-down tile to place next turn (or vice-versa).

It sounds simple, but it’s just complex enough to be fun—do you keep building a large contiguous area of one type of donut because that pays out immediately when it also likely offers up even more profit if the next player can build on it even further? Not to mention the ongoing tension of choosing whether or not to wait one more turn in hopes of getting an order card you need to box up a really big order of donuts is always at odds with knowing another player could get to some of those donuts before you if you do.

The game ends when there aren’t any more tiles or order cards to draw, and then everyone gets their last turn with whatever they have in their hands. After that, all that’s left is to lick your fingers, count the cash to see who won, and flick away the gross sprinkles.

We got the deluxe editions of the three games and therein lies one of my only criticism of the game: sometimes, less is more. I didn’t really need the donut hats (no, really, you get a four-pack of white cloth old-timey cloth hats) and a small expansion to the game rules via some extra tiles and order cards. This game also has cardboard standees you assemble to hold onto the tiles and order cards and we did build them but when it came time to put the game away, the box doesn’t really work well with those components, and there’s so much empty space in the box. This could have been a smaller, tighter game, which given it’s quick, would have made it a great “grab-and-go” game in a more portable package.

December 19, 2024

Tonight — PT’s Outspoken Reading Series: December Edition

December Will Be Magical Again

December Will Be Magical AgainHey all! I am super chuffed to be on an awesome lineup tonight in New York (alas, virtually in my case) with some fantastic authors courtesy of The Publishing Triangle’s OUTspoken Reading Series, and hosted by The Bureau of General Services: Queer Division. Now, if you’re lucky enough to be in New York right now, that’s happening in-person at the Bureau itself (Room 210 of the LGBT Community Center, 208 West 13th Street, NYC; tonight, December 19th at 7:00pm), but also it’s being streamed (which is also how I’m porting in via technology) and you can catch that live-streaming at YouTube.com/@BGSQD.

Said awesome line-up? Well, like it says above, you’ve got: Christopher Bram, Joy Ladin, Greg Herren, Christian Baines, Michael McKeown Bondhus, Finnian Burnett, Fiona Riley, and, oh, hey, there’s me there: myself, ‘Nathan Burgoine.

I’m going to be reading from Upon the Midnight Queer (though I’m still waffling over which story) and I’ve heard at least half of the other readers performing before and they’re awesome, so if you’ve got the spoons, the free time, and an internet connection? Ta-da! Plans! (And introverted, you-can-wear-your-PJs-plans at that! Don’t say I never did nothing for you.)

December 14, 2024

Wonder

Every December 14th for the past nine years, I’ve re-written a holiday story through a queer lens, retelling it as a way to retroactively tell stories to my younger self that include people like me. The first year, I wrote “Dolph,” (a retelling of Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer). Then I wrote “Frost,” (a retelling of Frosty the Snow-Man), “Reflection,” (a retelling of “The Snow Queen”), “The Five Crowns and Colonel’s Sabre,” (a retelling of “The Nutcracker and Mouse King”), “The Doors of Penlyon” (a retelling of “The Christmas Hirelings”), “A Day (or Two) Ago” (a retelling of “Jingle Bells”), “The Future in Flame,” (a retelling of “The Little Match Girl”), “Not the Marrying Kind,” (a retelling of “The Romance of a Christmas Card.”), and then last year, “Most of ’81” (a queer story inspired by “Christmas Wrapping”).

All of those stories are now included in a collection I released last month, Upon the Midnight Queer, alongside a new Little Village Novella included in the collection, “Folly,” which is a queer romance inspired by the poem “Jolly Old Saint Nicholas.” When I released Upon the Midnight Queer, and wrote “Folly,” I figured that would be this year’s retelling, but then I started to receive notes from people who’ve been reading this series of queer retellings for the last decade, and one or two of them said they couldn’t wait to see what story I chose for my blog this year, as reading the yearly retelling was something they looked forward to every year.

This goes to show I’m (a) open to flattery, and (b) hadn’t maybe thought through the reality of “Folly” being something you had to purchase if you wanted to read it. That’s on me, but this year, I’d also signed up for a writing retreat in the week leading up to today (I got home yesterday) and I devoted all that time to writing a new Village Novella, so I thought the window for coming up with a new story for the blog was closing before I could even open it.

The reason for this season’s offering is Giancarlo Herrera and Hannah Schooner’s wonderful performances in this collection’s audiobook.

The reason for this season’s offering is Giancarlo Herrera and Hannah Schooner’s wonderful performances in this collection’s audiobook.But then two things happened, really. The first was directly because of the writing retreat. Because of my injured arm and propensity for migraines, I forced myself to take breaks that would normally happen via Max (huskies are very good at putting you on a schedule where you leave your keyboard to walk them four times a day). While I was on those breaks, since I was working on a Village story, I decided to re-listen to the audiobook versions of the Village stories that came before: Handmade Holidays, Faux Ho Ho, and the new Upon the Midnight Queer (all performed by Giancarlo Herrera, joined by Hannah Schooner for Upon the Midnight Queer’s audio version, and he and they did such an amazing job on that I cannot even tell you). And I’d been listening to “A Day (or Two) Ago” while getting lost on foot on my way to an Arnprior Bakery (long story) but when I found the bakery, the second thing happened: “Walking in a Winter Wonderland” was playing on the stereo there and…

Well. This year’s story was scribbled in a notebook when I wasn’t at the keyboard, and when I got home, I rested my arm enough to make it possible to transcribe it today, so here’s the first of these queer retellings of holiday stories, carols, and songs to also be a sequel.

All thanks to a bakery, coincidence, and the wonderful talent and skill of Giancarlo Herrera and Hannah Schooner, I bring you “Wonder,” a queer retelling of “Walking in a Winter Wonderland,” and a revisit of Master Samuel Brunswick from “A Day (or Two) Ago.”

Wonder

WonderI’d been in my study working on a new tale when the winter night’s silence was broken by the softest trace of sleigh bells. At the barest hint of their crystalline, joyful noises, I lifted my gaze to the window, looking beyond the Manor grounds to the lane beyond, where snow glistened under the moonlight in the most delightful way, and felt a happiness rising in my chest alongside the wisps of golden light forming in the corners of my vision.

Spirits, I always thought of them, and they arrived more often than even before since Christmas last, when I’d made the acquaintance of a particular russet-bearded handler of horses. He was one Mr. Henry Wilson, the protege to the now late Mr. Edmund Pierpont, and as of the start of the previous holiday season—or three starts, if you counted things a certain way—he’d taken over the yearly tradition of my family hosting a series of sleighs the village could ride at their leisure.

In the morning, no doubt my eldest brother, who had returned for the season with his wife and daughter and the news of another child on the way, would claim his traditional right to the first sleigh ride. Likely, my middle brother and his new wife, the former Miss Fanny Bright, now Mrs. Fanny Brunswick, would claim the second sleigh for themselves, thereafter.

My parents didn’t often partake of the sleighs these days, both being of an age where the comfort of the indoors and fireplaces were of a greater draw, but I would find my way down to the stables as soon was proper.

After which propriety would be the last thing on my mind.

There! My first glimpse of that first sleigh and a powerful horse to pull it. I itched to go down to the stables right this very moment, though I knew I could not. My family might afford me some wilful dismissal over my career as a writer of some fame and monied successes enough to even make mention of it among the peerage, but wandering down to the stables on a cold winter’s night just to say hello the local horse breeder?

Likely that would be seen as odd, even for me.

As the sleigh bells rang and the brilliantly gliding sleigh and horse both cleared the final rise and came up the lane towards the already opened gate, I did, however, move my lantern to my window, and I raised a hand.

The figure in the sleigh waved back. The ringing bells, louder now, conjured golden spirits and ignited my muse as always. This time, they appeared as a whole murmuration of new, gold and shining birds, birthed of the wonderful sound of the sleigh bells, and swirling in an ever-changing cloud of light and joy and all of it orbiting Mr. Henry Wilson’s hand as he waved in my direction.

Oh, how sleep would evade me tonight.

*

The morning brought a wondrous land of winter perfection like those painted on the Christmas Cards my mother had purchased and written and sent with her wonderful mix of decorum and pious cheer. She’d confessed to have been unable to choose between two designs this year, and had instead ordered printings of both. Upon their arrival, my father had gently teased her, for to his eye they were so similar as to be identical, and I had to admit his point: two cards, both with pictures of the same cabin, though the latter from further away and framing the woods behind where the former had come up close and peeked through an open door to see a woman waiting at a table for a visitor.

They were perhaps a bit overtly sentimental for me, but deftly painted and charming, and my mother liked them, and it seemed to amuse her to choose which of the two variations to send to each of our peers.

But as I turned my gaze out the window to the layer of white glistening snow, and my eldest brother and middle brother did indeed announce their intentions to take the first two sleighs, it wasn’t the coziness of my mother’s paper cabins I imagined.

“I might take a walk later this morning,” I said, laying a foundation of deceit and rather enjoying the game of it. “I had some musings last night, and I need to allow them to settle properly in my mind before I attempt to put them to paper.”

My parents made noises that were assent enough, if of a variety best described as bemused, a state I confess I often drove them to. Neither John nor James paid much attention to my career, but the former Miss Fanny Bright leaned forward, engaging me in discourse in a way none of the rest of my family or in-laws tended to do, which had frankly been one of the truly most delightful things about her marrying my brother James.

“Another tale of adventure, or a fable?” she asked.

“I confess I haven’t even made it that far,” I said, trying not to gesture too wildly with my toast as I recalled the murmuration of bird-like spirits from the night before. “But I believe it will involve a new bird.”

“Delightful,” she said, while James eyed her with an expression I often spotted on his features since marriage: a sort of befuddled expression that I rather thought denoted he’d made at least some of the journey to understanding he had been outclassed, outsmarted, and outdone by his wife and should consider himself rather bloody lucky on all accounts.

I’d had a hand in that, truth be told, though perhaps it best be described as a finger.

The former Miss Fanny Bright had certainly handled most of it herself.

*

I waited until the fourth sleigh had left our stables, for it was always a quartet Old Mr. Pierpont had maintained, and I knew full well Mr. Henry Wilson would offer nothing less, and then bundled myself up for the winter air, exited the manor with as little fanfare or attention as I might gather, and headed for my “walk.”

That said walk entailed little more than a trek to the stables was of no concern to anyone else, frankly.

Henry looked up as I entered, and his gaze flitted past me, out into the snowy courtyard beyond, and though there were none behind me and none in earshot, he teased me with the most polite of greetings, and measured tone of respectability both.

“Ah, Master Samuel,” Henry said, putting his hands behind his back and squaring those wonderfully broad shoulders of his. “Good morning.”

Two could play this game.

“A good morning, Mr. Wilson,” I said, dipping my chin, though I confess no matter how much effort I put into attempting that cool, politeness my family had of speaking with those below their own social standing, I rather ruined my effort by allowing my eyes to speak as well.

My eyes, it must be understood, had more or less already professed I was there for the lips visible in Mr. Henry Wilson’s russet beard, and the rest could follow the bluebirds, which is to say, anything but those lips of his could simply go away, and not think of returning until at least spring.

Presently, we found a nook tucked to the side of the stables and greeted each other much more honestly, with a stolen kiss that had me rising somewhat on my toes—I need not repeat that I am not a tall man, as I am sure you recall this fact—but once stolen, that kiss did little to want me to return my feet fully to the ground again.

We stood there a moment together, until Henry let out a soft laugh, a noise of his I delighted in being the cause of. “Well,” he said. “These days are going to be a trial.”

He wasn’t wrong. Over the months, I’d managed to procure several interviews with him for my writing—I was half-way through a sextet of tales featuring man and horse, and they’d proven quite popular among my readers—and if those interviews had often required us to take to his private stables for me to ensure my details remained accurate, none had found fault with my determination for correctness.

Those interviews, however, occurred on the land he leased, rather away from the eyes of my family, the Manor servants, any villagers who might come along, or anyone else, for that matter.

“Meet me here tonight,” I said. “After all are asleep.” He’d be staying with the servants for the duration of the few days he and his sleighs were available for the Villagers, and I’d managed to arrange for him to have a room to himself, rather than a duet, and while I knew it was not possible to guarantee he wouldn’t be seen, he could likely invent a reason to be checking in on the stables at any hour of the night, were he pressed.

Henry put his warm, strong hand around the back of my neck and stole another kiss.

I confess I rather took it as agreement, but he followed it up with a barely breathed, “Tonight,” which was thoughtful and communicative on his part.

*

I often stay up later than the rest of the Manor and just as often dismiss the few servants to still feel an obligation to tend for my wayward self and my odd ways of settling at a desk and writing for hours upon end by lamplight.

As such, no real effort nor obfuscation was required for my plan, and while I confess to a single moment of setting my heart to a gallop when I thought I spotted someone in the kitchen, which instead turned out to be an apron on a hook, I availed myself of the delivery door and was outside under not a sky full of moonlight and stars as it had been the evening before, but one of fat flakes of snow that fell and chilled the nose and clumped together delightfully under ones boots.

Ideal, in fact, as any trace of my exit and return would both be covered by the morning. The notion struck me as particularly thrilling, and I aimed a festive smile of gratitude at the sky, to be delivered on my behest to the spirits of winter itself.

“Your complicity is appreciated,” I said.

The snow didn’t reply, of course, but I rather believe the flakes danced in a way best described as devilish.

I found Henry in the stables, as bundled as myself, his own nose already a trace pink, and he took my hand in his and tugged me through the rear of the stables and we walked amongst the snowflakes, hand in hand.

“It may be cold,” I noted, after we’d walked far enough from the Manor our voices wouldn’t carry. “But your company does lend ones spirit a boost.”

Henry laughed. “Oh, I love your way with words.” He paused our walk, turning me to face him. “I’m happy, too.”

This kiss was not stolen, but freely given, returned in kind, and compounded with interest at a most successful rate. Enough time was spent with it, in fact, that when he did pause for breath, his strong eyebrows had been dusted with the fat flakes that were falling all around us, and I reached up to stroke them clean again.

He turned his beared lips to my palm, and we invested a little more.

Finally, we walked again, neither of us wanting this evening to end, but both realizing upon reaching the meadow that this should be our farthest point. As children, it had been the same. My parents had often noted we were not to go further than here, which neither John nor James took as a particularly firm rule, but one to which I remained devotedly observant.

With a sly smile that tilted his beard to one side, Henry knelt, and gathered some snow in his gloved hands.

“If that is intended to become a projectile, Mr. Wilson, I shall have to throw myself at your mercy, for I’ve no skill in the art of war, not even with snow,” I said, holding up both hands in immediate surrender, the ghosts of snowball fights past with my brothers lining up in a series of humiliating reenactments.