Sam Newman's Blog, page 5

June 22, 2015

Answering questions (from Devoxx) on Microservices

I'm at Devoxx Poland this week, and my session was first up after the keynote. I got a load of questions via the Q&A system which I couldn't answer during the talk and which require more space than Twitter allows to respond to, so I thought I'd reproduce them here along with my responses.

I've tweaked some of the questions a bit for the sake of brevity, but I hope I haven't misinterpreted anything.

Sharing Code

I had a few questions on this, including:

Is it OK to share some code between multiple microservices? - Mariusz

And:

What is the best practice for sharing object like 'customer' between bounded contexts: model copy-paste, shared lib or just correlation Id? - Piotr ��ochowski

In general, I dislike code reuse across services, as it can easily become a source of coupling. Having a shared library for serialisation and de-serialisation of domain objects is a classic example of where the driver to code reuse can be a problem. What happens when you add a field to a domain entity? Do you have to ask all your clients to upgrade the version of the shared library they have? If you do, you loose independent deployability, the most important principle of microservices (IMHO).

Code duplication does have some obvious downsides. But I think those downsides are better than the downsides of using shared code that ends up coupling services. If using shared libraries, be careful to monitor their use, and if you are unsure on whether or not they are a good idea, I'd strongly suggest you lean towards code duplication between services instead.

Communication

How microservices should talk to each other? Is service bus best way to go? Can we somehow do p2p connections without loosing decoupling? - Dominik

Don't start with technology, start with what sort of interactions you want. Is it request/response you're after? If so, synchronous or asynchronous? Or does event-based collaboration make more sense in this context? Those choices will shrink your potential solution space. If you want sync request/response, then binary RPC like Thrift or HTTP are obvious candidates. If using async request response some sort of message passing tech makes sense. Event-based collab is likely to push you towards standard messaging middleware or newer stuff like kafka. But don't let the tech drive you - lead with the use case.

What's your take on binary protocols? - Tomasz Kowalczewski

I prefer textual protocols for service-to-service comms as they tend to be more hackable and they are less prescriptive (generally) in terms of what tech services need to use. But they do have a sweet spot. Protocols like Thrift and Google's Protobuffers that make use of schemas/IDL make it easy to generate client and server stubs, which initially can be a huge boon in getting started. They can also be quite lean on the wire - if the size of packet is a concern, they may be the way to go. Some of these protocols can be terrible though - Java RMI is very brittle for example and requires both client and server are Java-based systems. But start with what interactions make sense as above, then see if a binary protocol fits in that space. And if you do decide to go this route Protocol Buffers or Thrift are probably where you should start as they handle expansion changes pretty gracefully.

Size

How big should be microservice? - Prakash

And:

Can you give some advice on how big a micro service should be? - Marcin

42.

Seriously though, it does depend. LOC don't help us here as different languages are more or less expressive. I'd say how small a service should be for you is more down to how many services you can manage. If you are fairly mature in your automation and testing story, the cost of adding additional, smaller services might be low enough that you can have lots of them, with each one being pretty small. If everything is deployed manually on one machine with lots of manual testing, then you might be better off with a smaller number of large services to get started with.

So 'how big is too big' will vary based on your context.

Ownership

Do you agree with: "one microservice per team"? - Prakash

In general, yes. Services need clear ownership models, and having a team own one or more services make sense. There are some other ownership models that can work where you cannot cleanly align a service to a single team which I discuss in more detail in Chapter 10 of the book, and also on this site where I discuss different ownership models.

DDD & Autonomy

What's the key difference or decision making fact considering domain driven model and decentralization. seem to be contradictory when defining model & types - anonymous

Good question! I see DDD as helping define the high-level boundaries, within which teams can have a high degree of autonomy. The role of the architect/team leads is to agree the high level domain boundaries, which is where you should focus on getting a consensus view. Once you've identified the boundaries for services, let the teams own how you handle implementation within them. I touch on these ideas when discussing evolutionary architecture in Chapter 2 of the book.

Authorisation & Authentication

What is the Best way to profile one authorisation system for all Microservices? - Antanas

Technically, you can do this using a web server local to the microservice to terminate auth (authentication and authorisation), so using a nginx module to handle API key exchange or SAML or similar. This avoids the need to reproduce auth handling code inside each service.

The problem is that we don't really have a good fit for a protocol for both user auth and service-to-service auth, so you might need to support two different protocols. The security chapter of the book goes into more depth, but this is a changing field - I'm hopeful that OpenID Connect may be a potential solution that can help unify the worlds of human and service-to-service auth.

Transactions

How to go about transactions within microservice world? - anonymous

Avoid! Distributed transactions are hard to get right, and even if you do can be sources of contention & latency. Most systems at scale don't use them at all. If you're decomposing an existing system, and find a collection of concepts that really want to be within a single transaction boundary, perhaps leave them till last.

Read up on BASE systems and eventually consistency, and understand why distributed locks (which are required for distributed transactions) are a problem. To move from a monolithic system to a distributed system may mean dropping transactional integrity in some parts of your application, which will have a knock-on effect on the behavior of your system. That in turn can lead to difficult conversations with your business. This is not easy stuff to do.

Maintenance

When system goes into maintenance, isn't it more difficult to handle "polyglot" micro services than an ugly monolith using the same stack of technologies? - Pawe�� J

It can be. If the service is small enough, then this problem can be mitigated, as even if the tech stack is alien for the person picking it up they can probably grok it if it's a few hundred lines of code. But it is also a trade-off that each organisation needs to make. The benefits of polyglot services are that you can find the right tool for each job, embrace new tech faster, and potentially be more productive as a result. On the other hand in can increase the cost of ownership. Which choice is right for you should be based on the goals of your company, and your context. What's right for one company isn't right for all.

NodeJS

So we should more carefully go to nodejs? - anonymous

Personally, I am not a fan. Operationally, many people picked up NodeJS for microservices due to its ability to handle large numbers of concurrent connections and very fast spin-up time, an itch that Go scratches for me along with other benefits I don't get from Node. That said there is no smoking gun that says to me that NodeJS is a bad choice. Debugging is difficult, error handling can be fraught, and of course there is NPM and the crazy pace of change in the build tool and general library space, but lots of people use it, and love it, including many colleagues and clients.

So please feel free to put down my dislike of nodejs to a personal preference thing!

User Interfaces

In what way UI could be decomposed to microservices? - anonymous

Some argue that each microservice should expose a UI, which is then aggregated into a whole. For many reasons I think this pattern works in a very small number of cases. More often you'll either be making API calls from the API itself to pull back data/initiate operations, as this gives much more flexibility in terms of UI design.

In general, view UIs fundamentally as aggregation points. Think of your services as exposing capabilities, which you combine in different ways for different sorts of UIs. For web-based UIs this means making API calls to services to perform the required operations and return the appropriate data. There is lots of nuance here - this is unlikely to work well for mobile. Here using aggregating backends for your UIs can be required. I need to write up some patterns on this (I discuss them briefly in chapter 4 of the book) but it is an emerging space where there is no one right answer.

Versioning Endpoints

Why you version your endpoints on uris (v1,v2 example) not on accept header level ? - anonymous

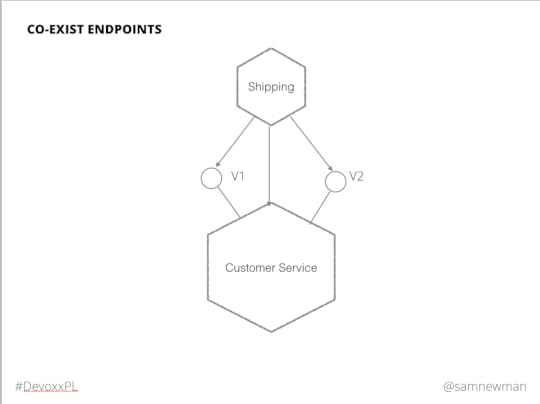

Here is the slide in question:

A slide form my 'Principles Of Microservices' talk where I show co-existing endpoints

This wasn't meant to define any specific implementation, and how you implement this pattern will depend on the underlying technology. For RPC this may need a separate namespace, or even a separate RPC server bound to a different port. For HTTP you have many options. You could do this using an accept header for example. However I tend to prefer having a version number explicitly in the path as it is much more obvious, and can be more straightforward to route., but I know many purists might be horrified at that thought!

Caching

Where to cache? Client or service itself? - anonymous

Cache in as few places as possible to start with. Caches are an optimisiation, so treat them as such, and only add them when needed. In general, I prefer caching at the server, as this centralises the cache and can avoid the need to cache the same data in lots of places, which can be efficient. However depending on the performance characteristics you are trying to meet, and the problems you have, this may or may not be the right answer. Sometimes you might want to do both!

Do though make sure you have metadata on any entities/resources you expose via APIs to aid caching, especially if you want to enable client-side caching. HTTP has very rich semantics for example to support this.

Performance

I also got a question via Twitter which I thought I'd fold in here too���

microservices increase latency due to network calls. How to solve for it? - @Aravind Yarram

Well, in a way you can't. You may be replacing what were in-process method calls with calls over the network. Even if you pick lightweight protocols and perhaps even go for non-blocking async calls, it will still be much slower, potentially by several orders of magnitude. We need to mitigate this by avoiding chatty services, and local caching, but even so there are limits.

I would turn this around. How fast does your app need to be? How fast is it now? By moving to microservices the additional latency due to network calls might end up slowing the app down (assuming this call is on the critical path), but if your app is still fast enough, that's OK. Microservices give, and they take away. Introducing them may make some aspects of your application slower. It's up to you to judge if that is an issue, and if you get enough benefits from them to make things worthwhile.

May 4, 2015

Coming Soon To A Conference Near You (Probably)

I seem to have bad luck recently...

And I thought March was a busy month���

Two weeks ago I was doing some work in Santiago, Chile, which coincided with a volcano eruption. From there, I headed to the enjoyable SATURN 2015 conference in Baltimore, which coincided with protests sparked by the tragic death of Freddie Gray. It was pointed out to me that when I went to XP Days Kiev last year, there was an incident at a nuclear facility just as I flew in, and given this worrying trend that perhaps I should let people know where I'm going to be for the next few months to ensure that people can make the appropriate travel plans. So here we go.

May

On Saturday, I fly out to the UK for my first SDDConf, in London. I'll be delivering a longer form of my "Principles Of Microservices" talk, as well as a one day version of the microservices tutorial. While in town I'll be doing a ThoughtWorks' hosted talk in the evening on operational concerns for Microservices. Then I'm off to Krakow, Poland, I'll be speaking for the 4th time at GeeCon. Aside from my talk I'll also be hosting a panel on microservices where I attempt to get people to say inflammatory things that work great as tweets which they will later regret.

Before heading home to Australia, I'll be making a pit-stop in Amsterdam for a Goto Nights talk on the 18th.

After a quick turnaround I'll be heading out again to my first time at Velocity in Santa Clara. It's been a goal of mine to speak at that conference, as for many years I've siphoned off the excellent videos O'Reilly put together after the conference, so to be speaking there is a real thrill. I'm also hoping to host an office hour there as well, but that hasn't yet been confirmed.

June

In June, I head back out to Europe. Firstly. I have NDC in Oslo where I'll be delivering tutorials on microservices, Continuous Delivery, and also finding time to do a talk too. I'm presenting at the local DevOps group as well. Then it's back to Krakow again for Devoxx Poland (the re-branded 33rd Degree conference). I had to pull out of talking there a couple of years ago so I'm very happy to be able to make it this time.

July

July is fairly quiet. I'm still hoping to squeeze in a visit to the local DevOps Days, this year hosted in Melbourne. I've attended the last two events (hosted previously in Sydney and Brisbane) but I might not be able to make it this time around given other commitments. I urge you to go along though if you're in Australia as it is an excellent event. But I will definitely be at UberConf in Denver, where I'll be delivering both a talk and a tutorial on microservices.

Rest Of The Year

Things quieten down a bit then, with only one confirmed conference so far which I'll share once the organisers announce the line-up. I do plan a couple of new talks to debut in the later half of the year as normal, probably on the topics of security and deployment. If you are interested in having me speak at your conference, then please do get in touch. I'm already booking things into October and November, so now is a good time to reach out!

Here's hoping my luck with local disturbances when I'm in town get a bit better for the rest of the year���

Multi-tenancy vs Single Tenancy

Previously, I spoke about a project some of my colleagues are working on, codenamed Asterix. The team are re-implementing a subset of functionality of an existing product on a new platform to create a cloud-based SAAS product. In my last post on the project I talked the thinking that was going on as to whether or not microservices make sense for Asterix, which is ostensibly a greenfield project. One of the things I didn't cover at the time was how decisions about how fine-grained to make your architecture can play into whether or not you go for a multi-tenant or single-tenant setup.

With a full Single Tenancy model, each customer runs on their copy of the system, with their own copies of the processes. The more customers you have, the more copies of the processes you need to manage. The more moving parts your system has, the more processes you'll need for each customer. This can be a reason against having finer-grained architectures - as the more fine-grained you go, the more processes per customer you need to manage. And those processes all need to run somewhere.

Most products, when moving from a traditional download model to a SAAS product offering, end up going with some flavor of multi-tenancy setup. The reason is efficiency. You can support more customers on fewer nodes, and fewer nodes means reduced cost. A single client setup might require lower-powered machines, but with more customers, you can provision higher-powered machines, which tend on the whole to provide more resources (CPU, Memory, IO) per $. A fully multi-tenant setup is more amenable to a microservice architecture than a single-tenant setup as the operational maintenance overhead doesn't scale linearly with customers. But they also allow you to scale individual parts of the system independently, allowing for a more cost-effective scaling too.

Containers have shifted things a bit. More than one SAAS provider has used containers in order to segment individual customers on their own instance of a particular service. Containers allow you to more densely pack isolated operating systems onto larger machines (which may themselves be virtual), albeit in a much cheaper way than standard virtualisation allows. The flip side is that you still have lots of processes running - those processes need to be managed just like any other, and now you have the added complexity of handling the container system itself, all of which have their challenges.

Containers can more easily open up hybrid models , where you might mix multi-tenant services with single-tenant isolated containers. It's far too easy to tell if that's a model that makes sense for Asterix. One aspect where this might come into play is that of data privacy. The issue is that a container-based model to isolate customer data can be problematic depending on the threat model, as most containers cannot be considered to be fully isolated.

Currently, the assumption is that Asterix will be using a standard multi-tenant model, but once we know more about the non-functionals regarding customer data the team may need to look at other options.

I've captured some patterns associated with these ideas, which I'll continue to update over time:

Single Tenancy

Multi-Tenancy

Hybrid Tenancy

You can find other patterns over in their own section on the site.

April 19, 2015

Microservices On Trial

I'll be delivering my Principles Of Microservices talk at SATURN 2015 in Baltimore. While there, I've been talked into being part of 'Microservices On Trial' which is being held on Tuesday evening. I'm sure Len Bass, Simon Brown and I will have some fun with the topic! I'm hoping it will be filmed, and if it is I'll post links to the video once it's available.

April 7, 2015

Capturing Patterns

While writing and presenting about microservices for the last few years, I realised I was seeing the same set of solutions (or problems) come up over and over again. While I was writing the book, I gave some of these reoccuring ideas names, but stopped short of calling them out as patterns in their own right. Increasingly however I realised that I needed some canonical references to the terms I have been using, and so the time was right to start writing up some of the patterns I have seen.

I already have a blog here at the site (you're reading it!), but a pattern and a blog post feel like very different things. A blog post is typically of it's moment. I tend not to go back and change a blog post unless there is a need for clarification, to fix a spelling mistake or because I got something very wrong. However the discussion and evolution of a pattern is a very live thing, and I wanted a cannonical URI that I could use to point people to these ideas.

This means that I'm going to be capturing the patterns on this website as a stand-alone place. I will revisit them, update them with examples and change them as I get feedback. I'm also terrible at naming things, so I suspect a few renames will occur too. One thing I do need to resolve is how to make people aware when there are changes to existing patterns. An ATOM feed which updates only when a new pattern is created is going to miss changes I make to existing patterns, but I also probably don't want the feed to spam everyone whenever I make a minor spelling correction. I'll have to think on that some more.

For the first batch of patterns I've written up a few different service ownership models. The Roving Custodian , Open Service Ownership and Temporary Service Ownership patterns cover off different ways of handling making changes to services that may not be owned by any one team, all of which can be useful when dealing with an Orphaned Service . I have a healthy backlog of other patterns to cover off on a range of topics including backlog management, security, and deployment models. Hopefully it'll keep me busy for the next few months!

April 6, 2015

Microservices For Greenfield?

I was having a chat with a colleague recently about the project (codename: Asterix) that they were working on. She was facing the question: Do we start monolithic, or start with microservices from the beginning of a greenfield project? While I do cover this off in a few places in the book, I thought it might be worth sharing the trade-offs we discussed and the conclusion we came up with to give you a sense of the sorts of things I consider when people ask me if they should use microservices. Hopefully this post will be a bit more informative than me just saying "It depends!".

Knowing The Domain

Getting service boundaries wrong can be expensive. It can lead to a larger number of cross-service changes, overly coupled components, and in general could be worse than just having a single monolithic system. In the book I shared the experiences of the SnapCI product team. Despite knowing the domain of continuous integration really well, their initial stab at coming up with service boundaries for their hosted-CI solution wasn't quite right. This led to a high cost of change and high cost of ownership. After several months fighting this problem, the team decided to merge the services back into one big application. Later on, when the feature-set of the application had stabilized somewhat and the team had a firmer understanding of the domain, it was easier to find those stable boundaries.

In the case of my colleague on the Asterix project, she is involved in a partial reimplementation of an existing system which has been around for many years. Just because a system has been around for a long period of time, doesn't mean the team looking after it understands the key concepts in it. This particular system makes heavy use of business rules, and has grown over time. It definitely works right now, but the team working on the re-platforming are new enough to the domain that identifying stable boundaries is likely to be problematic. Also, it is only a thin sliver of functionality that is being reimplemented to help the company target new customers. This can have a drastic impact on where the service boundaries sit - a design and domain model that works for the more complex existing system may be completely unsuited to a related but different set of use cases targeted at a new market.

At this point, the newness of the domain to the team leads me strongly towards keeping the majority of the code in a single runtime, especially given the changes that are likely to emerge as more research is done into the new potential customers. But that's only part of the story.

Deployment Model

Picture source, license

The cloud, only in your office

The existing platform is a system which is deployed at multiple customer locations. Each customer runs their own client-server setup, and is responsible for procuring hardware for the deployment, and has some responsibility for installing the software (or for outsourcing this to another party). This type of model fits quite badly for a microservice architecture.

One of the ways in which we handle the complexity of deploying multiple separate services for a single install is by providing abstraction layers in the form of scripts, or perhaps even declarative environment provisioning systems like Terraform. But in these scenarios, we control many variables. We can pick a base operating system. We run the install ourselves. We can (hopefully) control access to the machines we deploy on to ensure that conflicts or breaking changes are kept to a minimum. But for software we expect our customers to install, we typically control far fewer variables.

We also ideally we want a model where each microservice is installed in it's own unit of operating system isolation. So do our customers now need to buy more servers to install our software?

A couple of people at microxchg in Berlin asked me about this challenge, and I told them that until we see more commonly-available abstraction layers over core infrastructure (mesos, Docker, or internal PAAS solutions etc) that can reduce the cost of end-user installs of microservice-based systems, that this was always going to be a fraught activity. If you are operating in such an environment I would generally err towards again keeping the system more monolithic.

Picture source, license

Some modules are easier to reuse than others

Many vendors in this space look for module-based systems to provide the ability to hot-deploy new components as opposed to requiring multiple independent processes. Some of these module systems are better than others. I worked with a team on a content system based heavily on DayCQ (now part of Adobe Experience Manager) which made use of OSGI. One of the promises of OSGI is that you can download new modules or upgrade existing modules without having to restart the core system. In reality, we found this isn't always the case. Frequently it would be non-obvious what sort of module changes would require a restart, and much of the burden fell to module authors to ensure that this hot-deployment capability was retained. We felt that much of this was due to the problems associated with trying to shoehorn a module system into a platform that doesn't support it by way of a library. I really hope Java 9's Jigsaw module system will change things here.

Luckily for my colleague, one of the driving reasons behind them building a new version of the existing system is to roll out a multi-tenant, SAAS product, removing the need for customers to have to install and manage their own software. In fact, the client is open to the idea of deploying on to a public cloud provider like AWS, which has additional benefits as these platforms offer significant support in the form of APIs to help provision and configure our infrastructure. The one wrinkle in the case of the Asterix project is that there are some regulatory requirements about how data can be handled which may limit how readily we could use a public cloud. The team is investigating these requirements, but for the moment is working under the assumption that this will be hosted on a cloud provider somewhere, either public or private. Assuming this remains the case, it doesn't seem like constraints on our deployment model are going to be a barrier to using microservices.

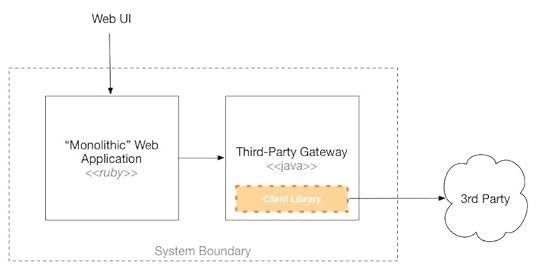

Technology

Multiple service boundaries allow you to use different technologies for different problems, giving you more chance to bring the right tool to bear to solve a particular solution. It also allows us to adapt to constraints that might exist in our problem space. One aspect of the Asterix project is the fact that there are significant integration requirements with a third party. This third party provides both C and Java libraries, and using the provided client libraries is a fairly hard requirement due to the complexity of interaction with the underlying service provider. If we were adopting a single, monolithic runtime, we'd then either need to use a stack that can integrate with the C library, or a Java platform where we could just use the Java library. Much of the rest of the system though really fits a simple web application structure, for which the team would lean towards a Ruby-based solution, using something like Rails or Sinatra.

The third-party handles sensitive data, and it is important this gets where it is going. In the current customer-installed, single tenancy system, when the third-party integration fails, it is obvious to the operator, the impact is clear, and they can just try again later. With a multi-tenancy approach, any outage or problem with this integration could have wide-reaching impact, as a single component outage could affect multiple customers.

The importance of this integration point, and the asynchronous nature of the comms with the 3rd party, meant that we may have to try some different things in terms of resiliency and architecture. By making this a service in its own right we'd be opening up some more possibilities in how we handle things.

The nature of the integration point itself also is a very clear boundary for us, one that is also unlikely to change given how stable it is for the existing product. This was what led my colleague to think of keeping this component as a separate, Java-based service. The rest of the standard web stack would then communicate with this service. This would allow us to handle resiliency of service to the third party within this stable unit, keeping the rest of the faster-moving technology stack in Ruby-land.

Ownership

As a consultancy, we have to handle the fact that the systems we build will need to be handed over and owned by the client in the long term. Although the clients existing system has been around for a fairly long time, their experience is in the design, development and support for a customer-installed client-server application, not a multi-tenancy cloud-based application. Throwing a fine-grained architecture into the mix from the off felt like a step too far for us. While working with the client we'll continue to assess their ability to take on this new technology and new ways of thinking, and although they are very keen it should still be a phased approach.

Another mark against going too fine-grained, at least at the beginning.

Security

This particular application has very sensitive data in it. We talked about some models that could protect it, including pulling out the especially sensitive data so that could be stored on a per-customer basis (e.g. single tenant one part of the application stack) or at the very least have it stored somewhere with encryption at rest. The industry this application is used in is highly regulated, and right now it is unclear what all the requirements are. The team plan to go and investigate what the regulator needs. It may well be that by decomposing the application earlier that we reduce the scope of the system that needs to be audited which may be a significant bonus.

Right now though these requirements weren't clear, so it felt premature to decide on a service boundary which would manage this data. Investigating this further remains a high priority though.

A Monolith, Only Modular

The initial view of what Asterix may look like

In the end it turns out that my colleague had already come up with the same thinking I did. Given what they currently know, the team is keeping the core system as a 'mostly monolithic' Ruby application, with a separate Java service to handle integration to the third-party integration point.

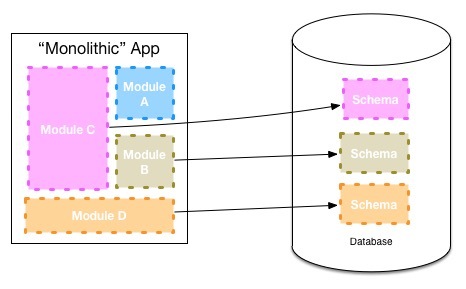

The team are going to look at is how to make it easy to split the ruby application at a later date. When deciding later on to make an in-process module a separate microservice, you face two challenges. The first is separating the code cleanly, and creating a coarse-grained API that makes sense to be used over a network rather than the fine-grained method calls we may permit inside a single process. The other challenge though is pulling apart any shared persistent data storage to ensure our two newly separated services don't integrate on the same database. This last point is typically the biggest stumbling block.

Keeping DB schemas separate for different modules

To deal with this, one of our internal development teams inside ThoughWorks decided that it made sense to map modules which they felt could at some point in the future become services in their own right to their own data schemas, as seen above. This obviously has a cost. But by paying this cost they kept their options open - pulling the service apart at a later date becomes easier as a result. The Asterix team are going to consider using the same approach within their ruby application.

The Asterix team will need to keep a close eye on the module boundaries within the main application code base. In my experience it is easy for what starts off as clear modular boundaries to become so intermingled that future decomposition into services is very costly. But by keeping the data models completely separate in the application tier and avoiding referential integrity in the database, then separation further down the line shouldn't be hugely challenging.

Better Brownfield?

I remain convinced that it is much easier to partition an existing, "brownfield" system than to do so up front with a new, greenfield system. You have more to work with. You have code you can examine, you can speak to people who use and maintain the system. You also know what 'good' looks like - you have a working system to change, making it easier for you to know when you may have got something wrong or been too aggressive in your decision making process.

You also have a system that is actually running. You understand how it operates, how it behaves in production. Decomposition into microservices can cause some nasty performance issues for example, but with a brownfield system you have a chance to establish a healthy baseline before making potentially performance-impacting changes.

I'm certainly not saying 'never do microservices for greenfield', but I am saying that the factors above lead me to conclude that you should be cautious. Only split around those boundaries that are very clear at the beginning, and keep the rest on the more monolithic side. This will also give you time to assess how how mature you are from an operational point of view - if you struggle to manage two services, managing 10 is going to be difficult.

It should be noted that this blog post outlines a discussion at a single point in time. As the Asterix team learn more, and the direction of the product they are creating changes, my colleague and her team may well find themselves having to change direction again. Architectural decisions like this are not set in stone - we just make the best call we can at the time. Having some framing for the decision making process though, as I have outlined above, gives you some mental models to use when assessing 'so what do we do now?'. It'll be fun to see where Project Asterix ends up - I may well blog about it again in the near future.

March 3, 2015

Three Simple Questions

At ThoughtWorks at the moment, I'm working with some of our internal teams and we're having a discussion around monitoring and alerting. A number of the systems we look after don't need 24/7 uptime, often only being required for small periods of time, for example around the end of month payroll systems. There are other systems we develop and maintain that are useful to our every day business, but again aren't seen as "Can't go down!" applications. This means that for a lot of our systems we haven't invested in detailed monitoring or alerting capabilities.

However, we really want to raise our game. Just because a system doesn't need to be up 24/7, it doesn't mean you shouldn't also clearly communicate when a system is down. We already do an OK job of alerting around planned downtime for many of our systems (although we are looking to improve), but we're more interested in getting better around the unplanned outages.

Now when the topic of monitoring and alerting comes up with delivery teams, especially when they are new to owning operational aspects of the applications they designed and implemented, this can seem like a daunting prospect. Both the technology landscape in this area and the number of things we could track are both large. The converstion investiably degenerates into discussions as regards to what metrics we should monitor, where they should be stored, which tool is best capable of storing them etc.

But, as a starter, I always ask the same few questions of the team when we start looking at this sort of thing. I feel they get fairly quickly to the heart of the problem.

What Gets You Up at 3am?

It's a very simple question. What would have to go wrong with your system for you to be woken up at 3am?

This is what gets to the heart of the matter. Talk about monitoring CPU levels fall by the wayside at this point. Generally the answer is "if the system isn't working". But what does that mean?

For a website it might need a simple ping. Or you could need to use a technique like injecting synthetic transactions into your system to minic user behaviour to spot when a problem occurs, something I detail in the book.

If the answer is "nothing", then this isn't a mission critical system. It's probably enough that every morning someone checks a dashboard and say "there's a problem!". Although the delivery team are far from the only stakeholders, as we'll discuss in a moment.

But if you are the unfortunate soul who has indeed been woken up in the early hours of the morning, there is another important question we have to ask.

When Someone Gets Woken Up at 3am, What Do They Need To Know To Fix things?

Telling them "What broke?" is obvious. But what do they need to do to find out why it broke, and what do they need to do to fix the problem? This is where you need drill-down data. They may need to see the number of errors to try and see when the problem started happening - seeing a spike in error rates for example. They may need to access the logs. Can they do that from home? If not, you may need to fix that.

This is where information which is one or two steps removed from an application failure is useful. Now is when knowing if one of your machines is pegged at 100% CPU is important, or seeing when the latency spike occured. This is why we need tools that allow us to see information in aggregate, across a number of machines, but also dive into a single instance to see what is going on.

The poor, bleary-eyed techie who got the wake-up call needs this information at their fingertips, where they are now.

Who Else Needs To Know There Is A Problem?

You may not need to be woken up at 3am to fix an issue, but other people may need to know there is a problem. This is especially true in ThoughtWorks, which is a global business with offices in 12 countries all over the world. For a non-critical system we may be completely happy for it to be down until the delivery team comes back to work, but we do need to at least communicate with people and let them know there is an issue and that it will be worked on.

Services like https://www.statuspage.io/ can help here. Automatically sending a 'serice down' notification at least helps people understand it's a known issue, and also prompts people to report a problem if the status page doesn't show an issue too. Things like http://www.pagerduty.com/ can also help, in terms of alerting out of hours support people to flag a ticket and indicate it's being looked at.

For a modern IT shop, even for non-mission critical software, being relentlessly customer-centric means communicating clearly with our customers via whatever channel they prefer. Find out who needs to know, and what the best is to get that information to them. They may be completely OK with you taking a day to fix an issue if you communicate with them clearly, but will be much less tolerant if they see nothing happening.

And The Rest

These three questions help drive out the early, important stuff around monitoring and alerting. It'll get you started. But there are a host of other things to consider. For example by doing trend analysis you may be able to predict failures before they happen. You may be able to monitor key customer-related metrics before and after the release of software that can help detect bugs in software. Or you could use all that lovely data to determine when your system will need to grow, or shrink.

You may also want to start thinking of game day excercises where you simulate failure and remediation mechanisms. This is a really interesting field, and I hope we can experiment with this ourselves more this year.

All that can wait though. Start with the easy stuff. Ask yourself three, simple questions.

Sam Newman's Blog

- Sam Newman's profile

- 172 followers