Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 78

September 15, 2016

Snowden Isn’t Paranoid Enough

The most dynamic scene of Oliver Stone’s film career—certainly the most electrifyingly bonkers speech he’s ever shot—came in 1991’s JFK. “It’s as old as the crucifixion, a military firing squad,” Donald Sutherland rants, laying out the conspiratorial case for the military-industrial complex assassinating the president. Cutting between Sutherland’s minutes-long monologue and sterling black-and-white footage of generals meeting in smoke-filled rooms, the sequence is a bravura display of paranoid filmmaking; the kind of work that means Stone is still being approached to make movies like Snowden, another tale of conspiracy at the heart of government in theaters this week. So it’s strange that his latest feature feels so devoid of both passion and paranoia.

Snowden is probably the most competent film Stone has made in a decade. It does a perfectly serviceable job retelling the story of Edward Snowden, the NSA contractor who leaked classified information about global surveillance programs and sparked an international conversation about government access to information in a digital age. But if you want a deep dive into the Snowden case, there’s already Citizenfour, Laura Poitras’s Academy Award-winning documentary that rigorously lays out the Snowden story. The substantial, proven details that drive the story of Snowden—the fact that the government can and has been spying on people through their cameras, phones, and computers for years—should be the spark to light Stone’s touchpaper. Instead, he’s delivered a solid, watchable biopic that utterly lacks the over-the-top flourishes that once made his films so compelling.

Stone has never imitated the staid, fact-oriented style of most biopics. Some of his best works (JFK, Nixon, and even Any Given Sunday, his take on the NFL) have taken real stories of shadowy abuses of power and blown them up to operatic proportions. But he had less fun with W., his George W. Bush opus that had a strange, chummy affection for its protagonist, and in recent years he’s seem lost, making a pointless Wall Street sequel in 2010 and the grimy, unmemorable drug-runner drama Savages in 2012. The Oliver Stone of the ’90s, who had such a good grip on the distrust of his post-Vietnam generation, might have done great work with his latest film. But the Stone of recent years, who has struggled to remain relevant in a more understandably fearful post-9/11 America, didn’t seem to know what to do with Snowden’s fascinating life and career.

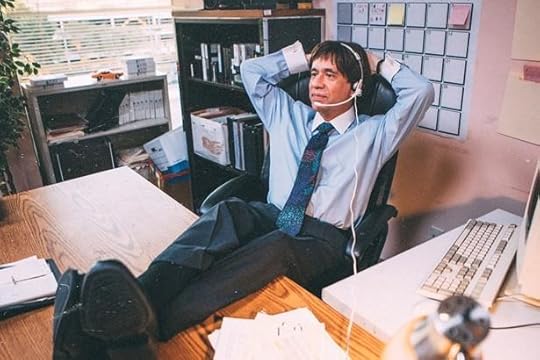

Still, he’s lucky to have Joseph Gordon-Levitt in the title role. Affecting a flat, croaky monotone and a shifty, withdrawn posture, the actor still manages to find some charm in the character, making the movie’s 140-minute running time much more bearable. Gordon-Levitt is best when he’s playing loners and weirdoes; his Snowden recalls the grumpy gumshoe of the high-school drama Brick, or the type-A dream-thief in Inception. He gave it his all as French acrobat Philippe Petit in last year’s The Walk, but his incessant exuberance for death-defying stunts came off as mostly creepy; as Snowden, where that same intensity is instead directed inward, he’s somehow alluring.

Because of that, you can see what the documentarian Poitras (here played by Melissa Leo) saw in Snowden as a filmmaking subject, and why the journalists Glenn Greenwald (a hilariously mean Zachary Quinto) and Ewan MacAskill (a grandfatherly Tom Wilkinson) almost instantly took Snowden at his word when he handed over reams of encrypted NSA data. Stone, who also co-wrote the film with Kieran Fitzgerald, cuts between Snowden dramatically handing over the data to journalists in 2013 and the ups and downs of his career in the intelligence community. The former has real stakes, but like any true story it’s hampered by viewers already knowing the outcome; the latter is seriously meandering.

Snowden feels trite in its efforts to depict America’s ensnarement in the creepy web of online spying.

There’s the spine of a great story in Snowden’s national service, beginning with an abortive attempt to join the Marines (he was discharged after breaking his legs during training), then switching to a promising career in the CIA. Snowden has its hero bump into spies who range from wildly unethical (Timothy Olyphant as a slick field agent) to staunchly principled (Nicolas Cage as an inspirational teacher at the academy). Rhys Ifans stands out as Snowden’s mentor, Corbin O’Brien, who is occasionally sinuous but more often happy to justify the agency’s creeping surveillance techniques as a necessary sacrifice for national safety. Though he quits the CIA out of ethical disgust, Snowden eventually becomes an NSA contractor, forever part of the swirling maw of tech experts paid to keep the nation safe.

Snowden does well to portray how middle managers in the intelligence community might come to these rationalizations; it’s just surprisingly even-handed for the typically skeptical Stone. The film feels irredeemably trite in its efforts to depict America’s ensnarement in the creepy web of online spying. As Edward realizes the reach of the NSA’s warrantless wiretapping, and its constant email surveillance, Snowden zooms out to horrendous CGI maps of glowing strings connecting people around the world, like some off-brand Windows 95 demo. At one point, as Edward has sex with his girlfriend Lindsay (Shailene Woodley), he eyes the gazing webcam of their open laptop with sweaty terror as the film blurs and fractures. These B-movie moments are supposed to help justify Snowden’s later decision to betray his country, but onscreen they’re blandly ineffective.

Woodley is perhaps the most under-served: A relatively stalwart presence at Snowden’s side, Lindsay puts up with a lot from him (he can’t talk about his job, appear in any pictures she takes, or really ever be cheerful about anything). In return, she’s handed the bulk of the story’s most boring material, designed to humanize a hero that Stone has already decided to canonize (the film literally ends with an audience giving Snowden a standing ovation). It’s Snowden’s scenes with the journalists, and his more subtle flickers of horror on the job at the NSA, that make him seem worth rooting for. Much of his personal life is just cruddy Hollywood padding for a movie that should be lean, angry, and focused. Stone used to be fearless in both the stories he told and the way he told them: Now, it seems, he’s just the former.

The Case Against Banning Offensive Words

This week, Instagram rolled out a new functionality: Users can now block specific keywords from appearing in their comments sections. The service is selling the tool (and users are celebrating it) as a “bully-blocker”—an acknowledgement that words can be weaponized to empower humanity’s worst tendencies. “Bitch”? “Stupid”? “Slacks”? Whether the words you don’t want to see are abusive or profane or simply empirically icky, you can now simply inform Instagram that you don’t want to see them, and any comments that contain them, regardless of their author or their grammatical context, won’t show up in your feed. Pooooof: gone.

The new capability whiffs on the one hand of what you might call civility theater. Instagram has been, as have its fellow social media services, hesitant to legislate among its users’ activities even when clear abuse has been involved (recall the racist depths to which @nero plummeted before Twitter finally kicked him out of its party). Here it is, now, essentially outsourcing its housekeeping responsibilities to its users. But the move, with its embrace of subjective censorship, also acknowledges a broader linguistic phenomenon: “Offense” itself is—and to some extent has become—a deeply individualized affair. Instagram’s ban-your-own-words functionality is tacitly endorsing one of the arguments that Benjamin Bergen, a UC San Diego cognitive science professor, makes in the new book What the F: What Swearing Reveals About Our Language, Our Brains, and Ourselves. Offense, like so much else, is relative.

Related Story

Swear Words, Blasphemy, and Justin Timberlake

Compare Instagram’s à la carte solution to, say, the workings of the FCC, which is empowered to decide on behalf of all Americans which words constitute a public “nuisance.” Or to those of the NFL, which regularly fines players for the f-bombs they drop on the field. Or to those of the MPAA, which via its partially language-based movie ratings system has been effectively issuing trigger warnings since long before it became politically complicated to do so. Instagram’s individualized anti-lexicon (lexi-non?) may be a superficial solution, considering the underlying problems that ultimately give offensive words their power; it is also, however, a deeply revealing one. Here is Instagram, taking the libertarian impulses of Silicon Valley to their logical linguistic conclusion: One man’s crass is another man’s treasure.

What the F’s title, much like its predecessors in the books-about-profanity genre, revels revealingly in its own cheeky euphemism. It’s a sweeping book, exploring not just the history of English profanity in words and in gestures, but also the impact that swears and other taboo words can have on the human brain. Even thinking about profanity, studies have suggested, can make people sweat more than they would otherwise. Employing it can increase people’s ability to withstand pain. Profanity can increase sexual arousal.

All of that is interesting, making What the F a valuable addition to the literature about profanity (which, Bergen notes, has been unfortunately scant). But it’s Bergen’s discussions of slurs, in particular, that form the most compelling, and urgent, sections of the book. Words may be innocent, as George Carlin put it—it may be their human context alone that give them their moral power—but slurs carry their own kind of violence. While we live, as Michael Adams argues, in “the age of profanity,” with Tumblrs like Fuck Yeah Kale and Twitter feeds like Shit My Dad Says (rendered on network TV as $#*! My Dad Says) and the many sheeeeeeits of The Wire, a slur still has the power to shock and abuse. To employ one, Bergen argues, “is the linguistic analog of closing your eyes and swinging in full knowledge that there’s a nose within arm’s reach.”

That would seem to make a good argument for banning slurs outright in public spaces, as has been the standard practice of the FCC and the NFL. But blanket bans of “indecent” language will almost always be self-defeating, Bergen argues. That’s because language, particularly in the age of the Internet, moves so quickly. (Take the speed at which suck and douche lost their shock value, and the speed at which contextually epithetic terms—queer, fag, slut—have been re-appropriated by the people they were meant to denigrate. Take, too, the haste with which recently novel terms—on fleek, yolo, basic-as-an-insult—now seem decidedly stale.) The story of swearing, Bergen suggests, is a story of serendipitous cyclicality: Words will sharpen, and then lose, their edges. “Dick” was a common English name for baby boys until, in the early 20th century, it obtained its anatomical associations. Archaic swears like swive (“to screw”) and fart-sucker (self-explanatory) were edged out of the standard English vernacular in favor of more modern innovations. Words meant to offend lose their luster when they become common; with their shock value thus smoothed and tempered, speakers and writers simply come up with new words to take their place.

So Instagram, yes, could have gone the way of the FCC, attempting to preserve decency from [bleeeeep] to shining [bleeeeep]. It could have issued a blanket ban on the words fuck and shit and their ilk. At which point millions of users, with intentions ranging from the cheeky to the malicious, would almost inevitably have responded with a flurry of “fvck”s and “shIt”s and revived “fart-suckers.” Instagram, basically, would have initiated an ongoing game of Whac-a-Mole against millions of endlessly creative human brains. It would have found itself permanently applying the Sisyphus filter.

So that’s one argument against blanket word-banning. But there’s another one—one that takes into more direct account the dynamics of offense relativity. Attempts to define “bad words” from the top down, Bergen argues, and particularly attempts to censor slurs, run the risk “of causing disproportionate and unfair injury to the very people it aims to protect.”

Had it gone the way of the FCC, Instagram would have initiated an ongoing game of Whac-a-Mole.

Take the n-word, and the many wide-spread and well-meaning attempts to ban it from public use in the name not just of some fuzzy notion of “decency,” but of empathy and respect and, you know, actual decency. In 2014, Colin Kaepernick, before he became the topic of national debate for words left unuttered, was fined for a word he (allegedly) did say: one that began with n. Context is key, as always, but the NFL, a private organization, decided that the 49er had indeed violated its policy against the use of “abusive, threatening, or insulting language or gestures,” and punished him accordingly.

What that policy doesn’t account for, however, is the linguistic variety of the n-word: It can be the most despicable, hated-filled term in the current iteration of the English language … but it can also be a term of endearment, and a verbal gesture of inclusion. (Indeed, so profoundly has the word evolved, Bergen points out, that some speakers have recently reconfigured it as its own pronoun.)

And yet: Kaepernick was fined. And so, who was harmed by the NFL’s attempt to regulate its way out of racial inequality? Colin Kaepernick. The policy meant to ensure that he be treated with respect ended up doing something that would seem to be decidedly disrespectful: punishing him simply for speaking. Here, again, offense is relative. As Charles Barkley put it in 2013, “I’m a black man ... I use the n-word. I will continue to use the n-word among my black friends and my white friends.” And as Bergen sums things up: “If someone thinks banning words is a silver bullet that will eradicate racism, sexism, heterosexism, or any other offensive ism, with no downside, he or she is mistaken.”

Which brings us back to Instagram and its insta-bans. The service’s workaround is not necessarily satisfying—it puts the onus on the abused, after all, to prevent future abuse—nor is it, scaled to television or other mass media, terribly practical. But it is, in its way, sensible. And more importantly it anticipates the direction that English—and the people who, in their varied ways, use it every day—is going. This is a cultural moment that is newly respectful of the individual experience, of the individual voice, of the individual truth. It is a moment that is grappling, belatedly, with the many flaws of mass media and monoculture; it is a moment that is respecting, finally, how varied people’s sense of the world can be. All of that involves, intimately, the words people choose to share that world with each other. In that landscape of fast-moving language, one person’s slur is another’s term of endearment. The regulatory body with the most authority to determine what will offend you is, in the end, you.

Glenn Beck's Payment to the Saudi Student He Accused of Financing Terrorism

NEWS BRIEF Glenn Beck, the conservative radio host, has settled a lawsuit brought against him by a Saudi Arabian man whom Beck accused of financing the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, despite strong evidence to the contrary.

Abdulrahman Alharbi, a Saudi student in Boston, was injured near the marathon’s finish line during the attack, in which two brothers planted bombs that killed three people and wounded 260 others. Less than a week after the bombing, Beck said his team had found a very “bad, bad, bad, man,” who was involved in the attack. He then threatened the government that if it did not reveal the man’s identity, Beck would. "I don’t bluff,” he said. “I make promises. The truth matters.”

Beck eventually singled out Alharbi as the “money man” behind the attack. To support this claim, Beck insisted he had received an inside tip from two Department of Homeland Security agents saying Alharbi was involved. When Beck was challenged on this information, he refused to name his sources.

Alharbi sued Beck in 2014, saying the radio host had damaged his reputation with his accusations, even though the FBI said Alharbi was not a suspect the day after the attack. The judge in the case said last month Beck must provide information to back up his claims. On Tuesday, he decided instead to settle out of court for an unknown amount of money.

As Politico reported, a statement included in the filing said:

No party has admitted any fault, wrongdoing, or responsibility as part of the settlement. Defendants have agreed to settlement of the pending action in furtherance of fundamental principles of journalistic integrity by preserving the confidentiality of their sources consistent with their rights and privileges under the First Amendment. The Plaintiff has pursued this action for the reasons set forth in his Complaint and believes those interests have been served by this resolution.

The case prompted debate over First Amendment rights, particularly over whether journalists should have to identify confidential sources, and the way the media treats private figures. Beck had resisted turning over his sources, and argued Alharbi was a public figure because he gave media interviews in the aftermath of the bombing. Judge Patti Saris, of the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts, ruled Alharbi was a private figure, which tipped the case toward Alharbi’s favor. The distinction between “private” and “public” is key here. If he were ruled a private figure Alharbi would only need to prove Beck acted negligently when he reported Alharbi financed the bombing; whereas if he were ruled a public figure, Alharbi would need to prove Beck intentionally falsified the information, or acted with reckless regard.

In Saris’ 61-page decision released last month, she said Beck had to offer some evidence to back his claims. A freedom-of-information-records request to the Department of Homeland Security offered no evidence linking Alharbi to the bombings. According to the Saris’ decision, Beck couldn’t turn over his notes because Beck’s producer, Joe Weasel, had written the tip on Post-It notes he later threw away.

September 14, 2016

The Trump Surge

Do you smell that in the air? No, it’s not the first breezes of fall. It’s the aroma of Democratic panic.

The latest trigger is a poll that CNN released late Wednesday afternoon. The poll shows Donald Trump beating Hillary Clinton 46-41 in Ohio, with Gary Johnson taking 8 percent, and Trump winning 47-44 in Florida, with Gary Johnson at 6 percent. Both figures are based on screening for likely voters, not just registered voters. A national CNN poll last week showed Trump winning by a point 49-48.

“This shouldn’t be close, but it’s close,” President Obama said at a fundraiser Tuesday night.

CNN’s poll of those two crucial battleground states is the latest in a series of polls that have shown good news for Trump. The gap between the two candidates has shrunk to one of its smallest points so far. Not since Trump’s post-Republican National Convention bump has the GOP nominee seemed to be in such a strong position. Certainly, mid-September has been decisive in presidential elections before. John McCain had built a lead over Barack Obama before the economy collapsed on September 15, 2008; McCain never recovered.

Of course, Trump also had farther to go to close that gap: With the exception of that bump, Trump has trailed in the race all along, and what’s changing here is momentum. Polling averages still show Clinton leading, and the forecasts from both FiveThirtyEight (64 percent change of Clinton win) and The Upshot (78 percent chance of Clinton win) show her with the edge. But those numbers have shrunk, and if the current trend continued, she could easily lose. As a Citibank analyst noted, in a comment that seems like it ought to be unnecessary but is not, “35% probability events happen frequently in real life.”

It’s that sort of idea that has some liberals flipping out. After all, this was supposed to be an easy contest! How can it be that a candidate who has lied repeatedly and blatantly, insulted minority groups, not bothered to learn anything about policy, and proposed banning Muslims from the country be even close to winning? Just a few months ago, even straight reporters were speculating that the race might be over, and that Trump had practically no way to win. Now, it looks like a nailbiter.

Or maybe all of this is wishful thinking from Trump fans and a classic example of what Obama adviser David Plouffe described as bedwetting, the tendency among Democrats to freak out and panic at the slightest sign of trouble. But privately, many Republicans who are horrified by Trump but have taken solace in the expectation that he would lose by a wide margin are starting to freak out too.

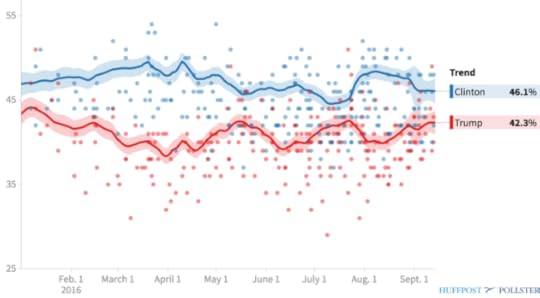

One interesting way to think about this is to look at Huffington Post Pollster’s polling average:

Clinton vs. Trump

What sticks out here is the Trump side of the graph. Clinton’s standing bounces up and down, but Trump follows a regular pattern. First, he has a ceiling right around 42.5 percent, and he’s never exceeded that. Second, at more or less regular intervals, he climbs up to that ceiling, and then he commits a grievous gaffe. In mid-May, he was flying high, but then the Trump University scandal and his attacks on Judge Gonzalo Curiel knocked the wind out of his sails. (Remember that? When Trump endorser Paul Ryan called his comments textbook racism? Strange times.) He then regained his standing at the RNC, just in time to pick a fight with Khizr and Ghazala Khan and tumble again.

One way to think through the current Trump boom is to watch and see whether he’s able to break through the magical 42.5 percent ceiling. Based on past experience, the key to that is whether he’s able to avoid committing another catastrophic error.

After months of failed “pivots” and “resets,” the newest Trump team does seem to have done a better job of keeping their candidate on message and, most importantly, on script. A campaign synonymous with bumbling has started to look nearly professional.

In part, that’s a triumph of bar-lowering, and it doesn’t mean Trump hasn’t said some bizarre things; there’s the burgeoning Trump Foundation scandal, too. It may be that there’s some fatigue setting in with Trump’s many outlandish comments, or it may be, as many progressives insist, that this is all the media’s fault for covering Clinton too harshly. But whatever the reason, he’s mostly managed to let the focus stay on Hillary Clinton, from her failure to hold press conferences to her continued email troubles to her recent illness. It turns out that staying out of the public eye helps Trump, just like it helped her during the weeks when she sat back and let him self-destruct.

In the meantime, will Clinton pick up on the panic among Democrats and panic herself? After a volatile 2008 campaign, she has run a low-key, stable operation this time around, other than rumors of a shakeup, never executed, after her poor showing in the New Hampshire Democratic primary.

Despite the run of strong polls, Trump faces some serious structural deficits. He’s struggling even among white voters, trailing behind Mitt Romney’s pace. He also has to contend with an electoral map weighted against a Republican, which means that Clinton can afford to lose a few swing states, while Trump has to be nearly perfect. It’s also common for Republicans to gain some ground when pollsters switch from measuring registered voters to polling likely voters, but it’s tough to know just what a likely voter is, especially because Trump has made little effort to build a large-scale get-out-the-vote operation.

Just as it was far too early to declare Clinton a prohibitive favorite two weeks ago, it’s far too early to declare Trump is on a path to victory now. But recent polling provides a useful corrective. Trump is still the underdog, but yes, he can win.

The NFL's $100 Million Investment in Concussion Research

NEWS BRIEF Following intense scrutiny over its handling of football players’ head injuries, the National Football League said Wednesday it would spend $100 million to fund research for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of concussions.

“The NFL has been a leader on health and safety in many ways, and we’ve made some real strides in recent years,” Roger Goodell, the NFL commissioner, said Wednesday in a letter. “But when it comes to addressing head injuries in our game, I’m not satisfied, and neither are the owners of the NFL’s 32 clubs. We can and will do better.”

Goodell said 60 percent of the $100 million will go toward improving football equipment, like helmets. The remaining funds will go toward medical research examining the long-term effects of concussions and treatment methods. The NFL previously donated $30 million to the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health for medical research in 2012.

The NFL has long been criticized for its inaction regarding the long-term health effects the game has on its players. A PBS Frontline report last year found that NFL players experienced 199 concussions in the 2015 season. And after 5,000 former NFL players filed a lawsuit against the league in 2014 for allegedly concealing the dangers of concussions from them, the league stated in court that nearly one-third of its retired players are expected to develop some kind of long-term neurological trauma.

The NFL’s announcement comes days after the league’s season opener, in which Carolina Panthers’ quarterback Cam Newton stayed in the game despite suffering repeated helmet-to-helmet hits. As my colleague Matt Vasilogambros noted, not a single penalty was given.

The Petrobras Scandal's Biggest Target

NEWS BRIEF Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the man who remade modern Brazil as its president from 2003 to 2010, has reportedly been charged in the country’s biggest-ever corruption scandal. The development comes two weeks after Dilma Rousseff, his political protege, was removed from office over a separate scandal.

Prosecutors allege that Lula, as he is widely known, and his wife did not disclose they owned a luxury, three-floor apartment in Guaruja, a resort town near São Paulo, that was built by a construction company implicated in the Petrobras scandal, which has ensnared some of the biggest names in Brazilian politics. Lula, his wife, Marisa Leticia, and six others have been charged in connection with the scandal, according to Reuters.

Politicians across the political spectrum, including from Lula’s Worker’s Party, have been implicated in a money-laundering scheme at Petrobras, the state-run oil firm and largest company in Brazil. In 2014, investigators uncovered an alleged decade-old, secret network of bribes and kickbacks at the energy firm, in which executives overcharged the company for construction contracts and funneled the extra cash to themselves, others, or politicians.

Brazilian police first alleged in March that Lula had benefitted from the Petrobras scheme. Last month, police recommended prosecutors bring the corruption charges against Lula and his wife for accepting bribes and laundering money. They alleged Lula received 2.4 million reals, or more than $700,000, in perks from the construction firm that built the Guaruja residence. Lula has denied any wrongdoing, and says he does not own the apartment in Guaruja. But the scandal is a serious blow to both his legacy, as well as that of his handpicked successor, Rousseff, who was removed from office last month because of a separate scandal—this one involving allegations she fudged budget figures ahead of presidential elections to make the economy seem healthier than it was.

Rousseff had served on Petrobras’s board of directors at the time of the alleged crimes, but she has not been directly implicated or charged with any wrongdoing. In March, while still in office, she named Lula her chief of staff, a Cabinet position that would grant him immunity from prosecution. A prosecutor in the Petrobras scandal then released tapped phone calls that suggested Rousseff gave Lula the job to help shield him from prosecution in the scandal. Days later, Brazil’s highest court suspended Lula’s nomination. The impeachment proceedings against Rousseff also began, marking the beginning of the end of her presidency.

In June, Eduardo Cunha, the legislator who led the impeachment movement against Rousseff but was later kicked out of office himself, was charged with money laundering in the same scandal. Lawmakers voted this week to ban him from running for public office.

The Year's Strongest Storm Sweeps by Taiwan

NEWS BRIEF Typhoon Meranti gathered in strength as it swept close to Taiwan on Wednesday, and with maximum winds of 230 miles per hour it has been called the strongest storm of the year.

Meranti was classified as Category 5, the highest on the scale. The storm has brought not only high winds, but also heavy rain, and many Taiwanese cities have flooded. Trains and shipping services in some southern cities had stopped, and most flights were grounded. As of Wednesday, there were only a few injuries. More than half-a-million people lost electricity.

Here's a look from a Typhoon Meranti from satellite, with Taiwan outlined in white:

Last #Meranti loop: check out the interesting gravity wave action likely in response to winds interacting w/ terrain pic.twitter.com/Xs1h5FEdE8

— Dan Lindsey (@DanLindsey77) September 14, 2016

And here's how strong some of the winds were:

So dangerous outside now in #Kaohsiung, stay inside people! #Meranti pic.twitter.com/JB3xiHMXJA

— Dave Flynn 茶米 (@DaveFlynn) September 14, 2016

Meranti did not directly hit Taiwan, but it came just two months after typhoon Nepartak hit the island. The worst storm to hit Taiwan in recent times came in 2009, when Morakot killed 700 people and caused about $3 billion in damage.

Typhoon Meranti is expected to travel north toward China, near the provinces of Guangdong and Fujian. It's predicted to reach land there by Thursday. If it does, it will be the strongest typhoon to hit the areas since 1969.

Ford's Mexico Move

NEWS BRIEF Ford Motor Company will transfer its U.S.-based small-car production to Mexico “over the next two to three years,” CEO Mark Fields said Wednesday.

The decision will send production of the Ford Focus and Ford C-Max Hybrid outside of the United States. Both models are currently manufactured at the Big Three automaker’s assembly plant in Wayne, Michigan.

A Ford representative told CNN the company plans to transfer production of other vehicles to the Wayne facility, and that no U.S.-based jobs will be lost as a result of the move.

Fields revealed the transfer during an investor briefing in Michigan. The Detroit Free Press has more:

"Over the next two to three years, we will have migrated all of our small-car production to Mexico and out of the United States," Fields said.

The industry has known for decades that domestic manufacturers struggle to make a profit on small cars. Shifting their assembly to Mexico can reduce costs to a point. But some of these cars are over-engineered.

For example, Field said the current Ford Focus can be ordered in 300 different configurations of options and colors. Ford wants to reduce that to 30, which will make the production process simpler and less expensive.

Ford’s move will likely provoke more criticism from Donald Trump. The Republican presidential candidate frequently denounced “bad” trade deals and the loss of manufacturing jobs to foreign countries on the campaign trail, and has often singled out Ford’s Mexico-based operations. The automaker previously drew his ire in April 2015 after it announced plans to build a $1.3 billion assembly plant there.

“This transaction is an absolute disgrace,” Trump told CNBC at the time, two months before announcing his presidential bid. “Our dishonest politicians and the special interests that control them are laughing in the face of all American citizens.” He later said he would impose up to a 35 percent tariff on Ford if they refused to bring foreign production back to the U.S.

Ford executives countered at the time by pointing out the company builds 80 percent of its North American vehicles in the U.S., and that it builds more vehicles in the country than any other automaker.

Documentary Now Is a Parody That Knows the Power of Nostalgia

IFC’s anthology series Documentary Now will always be a show of niche appeal, with its highly specific parodies of works ranging from Grey Gardens to Vice news docs. Its directors, Rhys Thomas and Alex Buono, pay such close attention to the films they’re mimicking that viewers can watch the original and the caricature side by side and detect choices as subtle as the use of jump-cuts, the font of the opening credits, or the lighting of an interview subject. The show’s stars, Fred Armisen and Bill Hader, elevate every episode with their performances, but it’s a comedy that wrings laughs mostly with its rigorous attention to detail.

The first episode of Documentary Now’s second season, airing Wednesday, is a twist on 1993’s The War Room called “The Bunker” where details as small as Armisen’s way of winking flirtily at the camera or Hader’s colorful assortment of garish sweaters manage to be spit-take worthy. The episode, written by the comedian John Mulaney, is a canny piece of nostalgia that captures the core of Documentary Now’s appeal: “The Bunker” virtually teleports viewers back to Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign in 1992, down to the wood-paneled walls and grainy VHS visuals. The series is a throwback whose humor hinges on unbelievable accuracy—both when it comes to the superficial elements and the deeper essence of the works being parodied.

In “The Bunker,” Armisen plays the campaign hotshot Alvin Panagoulious, analogous to George Stephanopoulos, a dreamy political whiz kid in 1992. Hader is Teddy Redbones, a toned-down version of his Jimmy Carville impression from his Saturday Night Live days. Together, they’re working on an Ohio gubernatorial campaign with the intensity of their real-life counterparts, though their client seems barely interested in attending the debates. While the War Room directors D. A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus wrought drama from dingy town-hall meetings and community events, its mockumentary version turns the sleepiest race possible into a viper’s nest of backstabbing and skullduggery as Redbones resorts to extreme tactics to get his man elected.

The best episode of Documentary Now’s first season was “The Eye Doesn’t Lie,” a parody of the true-crime masterpiece The Thin Blue Line. There, Armisen and Hader took the real people featured in Errol Morris’s film and dialed them up just slightly. Unlike when they were on Saturday Night Live, the actors seem to relish avoiding big catchphrases or obvious comedic tics. In “The Bunker,” Armisen’s Stephanopoulos impression boils down to a Beatles haircut and a baleful grin; “You think I’m a cute hunk?” Alvin asks his colleagues, resting his chin on his hand balefully. “I feel like I’m shy.” Redbones lacks the cartoonish snicker of Hader’s Carville impression, tutting quietly at campaign workers who disapprove of him hiring forgers to change his opponent’s yearbook quote.

The period details recall eras that viewers know and love, or works of cinema so famous their jump-cuts have become clichés. Even season one’s “Kunuk Uncovered,” a take on the documentary about the landmark 1922 work Nanook of the North, found a way to shake up a staid formula. Along with the graininess of The War Room, this season is tackling the sumptuous documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi (which becomes “Juan Likes Rice & Chicken”); the Maysles Brothers’ aching tale of Bible hawkers, Salesman (now “Globesman,” about door-to-door globe sellers); and the Talking Heads concert movie Stop Making Sense (“Final Transmission,” a music parody featuring Maya Rudolph).

In a Peak TV world, there’s an audience (however modest) for the kind of obsessiveness on display in every week of Documentary Now, especially since three Saturday Night Live alums are behind it. Even viewers unfamiliar with the original works being parodied will find plenty to enjoy, but the show’s chief draw is undoubtedly tied to its source material. Every mini-movie has a strange humanity to it, looking to echo the heart of the subject, as well as the style. “Juan Likes Rice and Chicken” recognizes that Jiro Dreams of Sushi was a story of sons grappling with the legacy of their father’s genius. “The Bunker” knows that viewers have some affection for an era of politics where battles weren’t fought online, but in grimy campaign offices. There’s an art to parody that goes beyond imitation, but doesn’t work without it, and Documentary Now is one of the only shows on TV these days that understands that.

Australia's Same-Sex Marriage Debate

NEWS BRIEF Malcom Turnbull, the Australian prime minister, introduced legislation Wednesday to enable a public plebiscite on same-sex marriage in February. But without the support of the opposition, center-left Labour Party, it remains unclear if such a vote will take place.

“Our opponents argue that the Australian people are too immature and to reckless to be trusted with this debate,” Turnbull said of the plebiscite in a statement Wednesday. “This insults and disrespects the Australian people.”

Turnbull, the leader of Australia’s conservative Liberal Party, has advocated for giving all Australians a say in whether existing laws on same-sex marriage, which is illegal in Australia, should be changed. Though the vote, which would be compulsory for all voting-eligible Australians, is non-binding, Turnbull said a “yes” vote would respected by Parliament.

Opposition leaders have voiced concern over the plebiscite, arguing instead Parliament should legalize same-sex marriage without a referendum, which they say would only result in a divisive—and expensive—public debate. The state-run Australian Broadcasting Corporation reports the Cabinet has agreed to allocate $7.5 million each—$15 million total—to the “yes” and “no” campaigns.

Bill Shorten, Labour’s parliamentary leader, condemned the plebiscite and accused Turnbull of being a “fraud on marriage equality,” suggesting his party would block the vote, which requires support from at least nine senators to pass the Senate.

“I am gravely concerned about the plebiscite and over the coming days and weeks, we will be sitting down with people affected, families and mental-health experts about the harm a plebiscite will cause,” Shorten said Tuesday in a statement. “Malcolm Turnbull has no idea of the harm this could inflict on so many people and their families.”

Several LGBT groups echoed similar concerns in a joint statement Wednesday, calling on Parliament to respect the views of the majority of Australians who support marriage equality by legislating in their favor, instead of deferring to a national vote. They said:

Our shared goal is simple—we want marriage equality as soon as possible at the lowest cost. … The Government proposes a plebiscite which we believe is unnecessary, costly and divisive, when the law can be changed through a straightforward vote in parliament. No Australian should have to witness a national debate on their worth or the value of their relationship.

According to a study by Essential Report, 57 percent of Australians support changing the law to permit same-sex marriage, with 28 percent voting against and 15 percent voting as unsure. The majority of those supporting same-sex marriage are between the ages of 18 and 34, and overwhelmingly belong to either the Green or Labor parties.

Australia is one of the few Western countries where same-sex marriage isn’t legal.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower