Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 346

September 16, 2015

At the Broad Museum, the Architecture Rivals the Art

Los Angeles’s newest contemporary art museum, the Broad, sits across the street from Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall. Few buildings could be expected to rival the space-age angles of Gehry’s iconic 2003 structure, but the Broad certainly tries, presenting itself as a work of art on par with the contemporary masterpieces it was built to house.

When it opens on September 20, the Broad will become the city’s second richest museum behind the Getty—its endowment of $200 million is more than the endowments of the neighboring Museum of Contemporary Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art—as well as the latest edition to the developing downtown arts district. Commissioned by the billionaire philanthropist Eli Broad and his wife Edythe, the $140 million museum will showcase and store the couple’s more than 2,000-piece collection.

Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the New York architecture firm best known for the High Line in Manhattan and the Contemporary Institute of Art in Boston, designed the 120,000-square-foot museum with the dominating Walt Disney Hall in mind. In contrast to Gehry’s smoothly curved titanium panels, which make up a haphazardly layered, extroverted facade, the Broad is solidly square with an asymmetric base and a matte exoskeleton of an exterior made of fiberglass-reinforced concrete. The honeycomb facade diffuses natural light inside the building and compliments the skylights on the roof while keeping the Broad’s considerable collection of post-war art safe from overexposure.

Iwan Baan / The Broad

Iwan Baan / The Broad The cavernous lobby, finished with undulating walls, is stark, with attention directed toward a massive escalator that takes visitors up to the third floor gallery, the museum’s main exhibition space.

Iwan Baan / The Broad

Iwan Baan / The Broad On their way out, visitors descend through a staircase that was constructed so that works stored in the museum’s central vault can be glimpsed—a tease to inspire future visits and reveal the extent of the Broads’ collection.

Iwan Baan / The Broad

Iwan Baan / The Broad Christopher Hawthorne, the architecture critic at The Los Angeles Times, finds the museum’s “veil and vault” design—referring to the “veil” of the external honeycomb and the “vault” of the building’s central storage and administrative areas—“perfectly clear, if rather prescriptive.” The Broad, he says, is “a far more rational and constrained building than it initially appears.” However, Hawthorne commented that the museum’s design has personality on the periphery: in the museum’s glass elevator, in the small gallery adjacent to it, and in the delicately lifted edges of the building’s facade.

The Washington Post’s architecture critic Philip Kennicott has praised the building’s architecture despite its imperfections, calling it “a narthex for the age of distraction, allowing the mind to rebirth itself into a state of greater focus and spiritual expectation.” The problem isn’t the building, he’s noted, but its collection.

Iwan Baan / The Broad

Iwan Baan / The Broad The art—the ostensible main event of the museum—hasn’t yielded positive reviews, despite the museum’s housing one of the most anticipated private collections of contemporary art. The Broad’s art checks all the “blue-chip-masterpiece” boxes, with works from the likes of Jeff Koons, Roy Lichtenstein, Joseph Beuys, Damien Hirst, Sharon Lockhart, Kara Walker, and Andy Warhol, not to mention the world’s largest collection of Cindy Sherman pieces. But it’s precisely this overwhelming presence of “universal collection staples,” argues Holland Cotter in The New York Times’s review of the museum, that shows that the Broad is old-fashioned rather than forward-thinking; it has been built to “preserve a private collection conceived on a masterpiece ideal” rather than making room for the “under-known, offbeat, less than neat.”

Still, the museum will be open to the public for free, part of a growing trend for museums to lower their barriers to public enjoyment. “We have been deeply moved by contemporary art and believe it inspires creativity and provokes and stimulates lively conversations,” Eli Broad said in a statement. “We hope visitors from Los Angeles and around the country and the world visit and are similarly enriched by this art.”

Warren Air / The Broad

Warren Air / The Broad The Broad’s opening is the first of several large-scale projects in L.A. over the next few years, including a movie museum funded by the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, a redesign of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and a new 100,000-square-foot art space from Hauser & Wirth, the contemporary art powerhouse.

“I think there’s a recognition that the city matters, that the people aren’t just there for the weather,” Kathy Halbreich, the associate director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, told The Washington Post last year. “You see a level of ambition that’s been ratcheted up.”

September 15, 2015

Elton John's Special Relationship With Russia

Among the more pressing international disputes of the week is the question of whether Vladimir Putin rang up Elton John. John’s Instagram post on the matter is pretty unambiguous—“Thank-you to President Vladimir Putin for reaching out and speaking via telephone with me today,” he wrote Monday. “I look to forward to meeting with you face-to-face to discuss LGBT equality in Russia.” But a representative for the Kremlin later said that the call never happened.

The alleged communication would have followed a conversation between John and the Ukranian leader Petro Poroshenko about the subject of gay rights, after which the singer told the BBC he wished he could have a similar chat with Putin about Russia’s laws targeting “gay propaganda.”

If Putin did indeed reach out to Elton John, rather than to any of the many other Western celebrities who have decried Russia’s treatment of gays in the past few years, it wouldn’t be the strangest thing in the world. John has a long relationship with the country—historical roots, many fans, musical compatibility. In 1979, he became the first major Western pop star to perform in there, and Cold War tensions were high. “I knew we were being watched all the time: I had an interpreter that they’d clearly set up,” John recalled to The Guardian in 2013. “Actually, I ended up having sex with him on the roof of my hotel.”

“Russians heartily embrace performers that embody anything other than the country’s avowed heteronormative ideals.”In recent years, John has resisted calls for Western stars to boycott the country—and defied Russian antigay protestors—by making pro-LGBT political statements during his tour stops there. “‘On one hand, I want to say, ‘I’m not going and you can go to hell, you guys,’” he told Terry Gross two years ago. “But that’s not helping anyone who’s gay or transgendered over there … I’ve always had a wonderful rapport with the Russian audiences and with the Russian people … I, as a gay man and a gay musician, cannot stay at home and not support these people who have been to lots of my concerts in the past.”

Is it strange that an openly gay performer like John would have a fervent fanbase in Russia, given its reputation for homophobia? Not necessarily. As The Atlantic’s Olga Khazan has written, “whereas flamboyant artists might be marginalized in other, similarly conservative nations, Russians heartily embrace performers that embody anything other than the country’s avowed heteronormative ideals. From Sergey Zverev, who sings decked out in long blond tresses and blush, to Zemfira, a fierce tomboy rumored to be having an affair with an actress, many of the country’s most renowned musicians are (or appear to be) gay, bisexual, or cross-dressing.”

Another point: Putin plays piano.

Sanders and Kennedy at Liberty, 32 Years Apart

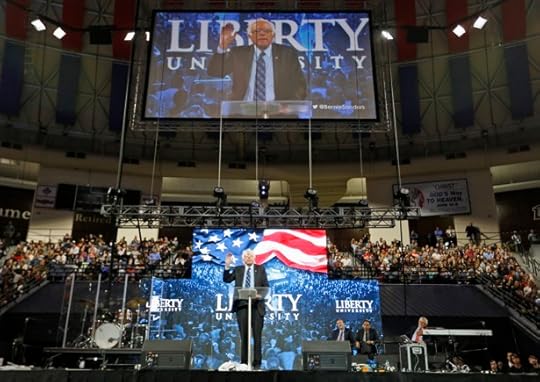

When Bernie Sanders stepped to the podium on Monday at Liberty University, he was not the most famous liberal to speak at the well-known bastion of Christian conservatism.

That title still belongs to the late Ted Kennedy, who delivered an address there on religious tolerance 32 years ago at the invitation of the Reverend Jerry Falwell, the founder of both Liberty Baptist College (as it was then known) and the nation’s ascendant “moral majority.” Kennedy’s appearance in Lynchburg was even more surprising at the time; while he was the bête noire of conservatives during the Reagan era, he was three years removed from his presidential run and had already decided not to seek the White House in 1984.

Despite their reputations as Democratic partisans, both politicians were received warmly by the student crowd. Kennedy broke the ice by opening with a series of jokes about the unlikely invitation from Falwell. (He invited Falwell to deliver the invocation at the inauguration “of the next Democratic president” in 1985, and he quipped that in exchange for Falwell allowing the Liberty students “an extra hour before curfew on Saturday night,” he had agreed to watch the reverend’s “gospel hour” on Sunday morning.)

Below is Falwell’s introduction and the opening of Kennedy’s speech. The full audio of the address is available here.

Falwell died in 2007, and it was his son and namesake, Jerry Falwell Jr., who introduced Sanders on Monday. The Democratic presidential upstart skipped the humor, but he had an advantage that Kennedy didn’t have: As Falwell Jr. noted, the university made room for Sanders’s supporters to sit in the front rows of the arena, giving him cheering sections that suggested, at least on video, a more enthusiastic response to his speech than might have been the case.

In substance, the speeches were most similar in what Kennedy and Sanders chose not to do: Neither liberal tried to persuade the conservative crowd of the wisdom of abortion rights or gay rights. They each acknowledged their differences, extolled the importance of preaching beyond the choir, and then turned to topics where they believed they might find common ground. Yet the two liberal-in-the-lion’s-den speeches were fascinating as reflections of two particular and divergent political moments.

In the mid-1980s, there seemed to be little dispute that Falwell’s Moral Majority was just that. With strong support from the Christian Right, Reagan won a convincing victory in 1980, and when Kennedy spoke in 1983 (the “Year of the Bible,” as declared by Reagan), the Republican was heading toward an outright electoral landslide in 1984. In that context, Kennedy’s tone bordered on the defensive. He made little attempt to win over the crowd to his issues, instead arguing merely that they should let dissenters be heard. Religious conservatives may have a majority, but no one has “a monopoly” on the truth, Kennedy insisted.

While arguing that religious institutions should weigh in on policy debates that hinge on questions of morality, Kennedy issued a reasoned defense of the separation of church and state and warned that without it, “today's Moral Majority could become tomorrow's persecuted minority.”

In short, I hope for an America where neither "fundamentalist" nor "humanist" will be a dirty word, but a fair description of the different ways in which people of goodwill look at life and into their own souls.

I hope for an America where no president, no public official, no individual will ever be deemed a greater or lesser American because of religious doubt -- or religious belief.

I hope for an America where the power of faith will always burn brightly, but where no modern Inquisition of any kind will ever light the fires of fear, coercion, or angry division.

I hope for an America where we can all contend freely and vigorously, but where we will treasure and guard those standards of civility which alone make this nation safe for both democracy and diversity.

Three decades later, Sanders spoke at Liberty under very different circumstances. Surging in the polls as he seeks to succeed a Democratic president, he has the political wind at his back. Religious conservatives, by contrast, have just suffered a generational defeat with the nationwide legalization of gay-marriage, and supporters of abortion rights have successfully fended off each major challenge to Roe v. Wade for 40 years.

While Sanders steered clear of those issues until the question-and-answer part of his appearance, he made a much more assertive case for liberal economic policies. Indeed, what was most notable about his speech to the conservative Liberty crowd was how little he deviated from the core message of his candidacy. Sanders sought directly to enlist the support of evangelicals in his fight against income inequality, framing his support for the poor in moral terms.

Amos 5:24, "But let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream." Justice treating others the way we want to be treated, treating all people, no matter their race, their color, their stature in life, with respect and with dignity.

Now here is my point. Some of you may agree with me, and some of you may not, but in my view, it would be hard for anyone in this room today to make the case that the United States of America, our great country, a country which all of us love, it would be hard to make the case that we are a just society, or anything resembling a just society today.

Sanders returned to the concept of “justice” throughout his nearly 30-minute speech. “In my view, there is no justice, and morality suffers when in our wealthy country, millions of children go to bed hungry,” he said. “That is not morality and that is not in my view is not what America should be about.”

Along with other Democratic politicians, Sanders has cited approvingly the critique of financial greed by Pope Francis, and he did so again at Liberty. Kennedy, by contrast, spoke during an era when the poor were often blamed for their lot in life, and he made only a glancing reference to the idea of helping the needy as a moral imperative. “We are sometimes told that it is wrong to feed the hungry, but that mission is an explicit mandate given to us in the 25th chapter of Matthew,” he said.

Just because Sanders felt confident enough to deliver a progressive stump speech to conservatives at Liberty University doesn’t mean that he was effective in winning them over. He received enthusiastic cheers from some in the crowd of nearly 12,000 throughout his speech, but the loudest and lengthiest ovation of the appearance came not when Sanders was speaking, but when Liberty’s senior vice president, David Nasser, pressed him on whether his desire to care for the nation’s children extended to those “in the womb.” Sanders responded by appealing to the conservative belief in limited government as an argument for leaving the question of abortion to women and their doctors. It received a much more subdued reaction.

The political overlap between a liberal Democrat and the evangelicals of Liberty University may be greater in 2015 than it was in 1983, but it’s not an alliance just yet.

Facebook Says It's Introducing a 'Dislike' Button

For more than six years, every Facebook status, photo, or page has had a little “Like” button hovering next to it. Want to show your approval? Click that button.

But not everything in the world is meant to be approved. And—nearly since the “Like” button first saw the light of day—users have clamored for an “Unlike” button. Now, they may be getting their wish.

On Tuesday, Mark Zuckerberg, the company’s founder and CEO, told an internal corporate Town Hall that Facebook would soon be rolling out the feature.

“I think people have asked about the dislike button for many years,” Zuckerberg said, according to Re/Code and Business Insider. “Today is a special day because today is the day I can say we’re working on it and shipping it.”

Zuckerberg added that the “Dislike” button wouldn’t work like Reddit’s up- and downvote mechanism, which is probably the most famous “dislike” button on the Internet. Instead, he said, users would now have a technical way to express regret or sympathy in a situation.

“What they really want is the ability to express empathy. Not every moment is a good moment,” he said.

Zuckerberg’s commitment to shipping such a button is new, but his interest in giving users an option other than “Like” is not. Late last year, he said he wanted to build a non-like button but hadn’t settled on the right language yet. And back in December 2013, programmers at Facebook’s compassion-themed hackathon proposed introducing a “Sympathize” button.

Designing for all the moments in life—not just the happy ones—has also been the subject of some thought from major technology companies lately. Last year, a post by the early web developer Eric Meyer about the “inadvertent algorithmic cruelty” of Facebook’s year in review feature went viral and prompted an apology from the company. And last month, many critics (including myself) argued that Twitter and Facebook’s auto-playing video feature failed to account for the full scope of events (and horrors) that could be captured on film.

So will “the Dislike button” that Zuckerberg is discussing take the form of an actual “Dislike” button adjacent to the thumbs-up of “Like”? I’m not sure. Will Oremus, a technology reporter at Slate, hypothesizes on Twitter that he’s “pretty sure it’s going to be like a suite of alternatives to ‘Like,’ one of which may or may not actually be the word ‘Dislike.’” The original Re/Code report wonders if Facebook’s feature will resemble Slack’s new emoji responses, which allow any user to respond to a message with any emoji.

Myself, I wonder if the message that Facebook really wants to convey with a “Dislike” button—which is something like I’m sorry, I sympathize, I feel you—is best conveyed by a heart. The company already slides a thumbs-up next to all its posts, a universal symbol of approval. Why not also insert a cartoonish heart? In various situations, ♥ can represent joy, anguish, empathy, and adoration. Much like the word “friend,” in other words, it is already wonderfully multivalent—an ambiguity that Facebook can exploit, as it becomes a messenger of thought and feeling for more than 1 billion people every day.

Breyer v. Colbert

U.S. Supreme Court justices don’t typically appear on late-night TV, so Justice Stephen Breyer’s visit to the Late Show with Stephen Colbert could have been something special. Instead, it felt like a missed opportunity.

Breyer, fresh off one of the Supreme Court’s most historic terms in decades, received second billing to Emily Blunt, who promoted her upcoming action film. The justice’s slow, measured tone didn’t really gel with Colbert’s bantering interviewing style. Breyer didn’t get a chance to discuss his new book, which ponders the Supreme Court’s evolving (and controversial) relationship with foreign legal thinking. Questions about jurisprudence or recent decisions were neither asked nor answered. But Breyer had a chance to give a convincing argument against cameras in the courtroom, and he emphatically defended the Court’s collegiality from Colbert’s hints of acrimony.

Journalistic interviews with the justices are increasingly common and often good, but rarely great; New York magazine’s 2013 conversation with Antonin Scalia is a delightful exception. All nine of them speak often in public, although their audiences are usually law schools, state bar associations, judicial conferences, or similar law-related organizations. Some justices occasionally make unconventional appearances, like Sonia Sotomayor’s visits to The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and Sesame Street. But lawyers talking to lawyers is the norm.

That could change, however. UC Irvine law professor Rick Hasen provided some interesting data about their public appearances in a recent study. All of the current justices have been more public than their predecessors, save for Justice Arthur Goldberg, who spoke frequently about anti-Semitism during the 1960s. Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg tend to receive more press for their remarks, but Breyer actually holds the record for the most public appearances by a justice since 1964.

Are these public appearances good for the Court? Judge Richard Posner, a popular federal appellate judge in the Seventh Circuit, disapproves of what he calls the justices’ “public intellectual” activities. At the same time, he doesn’t see them as a threat to the Court’s legitimacy, since institutional support for the Court remains relatively high. Besides, he adds, few Americans can even identify individual justices. Colbert also observed before his chat with the justice that 3 percent of Americans know who Breyer is. The rest, he joked, confuse him with Mr. Burns from The Simpsons, with whom the justice shares a vague resemblance.

But by my count, Breyer has elevated two significant legal issues within the past year: the death penalty, in his dissent last term renouncing it in Glossip v. Gross, and—in his new book—the globalization of American law. Breyer also appeared alongside Justice Anthony Kennedy at a House Appropriations Subcommittee hearing on the federal judiciary’s budget in March. There, Breyer criticized mandatory-minimum sentences and Congress’s piecemeal approach to sentencing. Kennedy also criticized mass incarceration and solitary confinement more broadly.

The nine justices are—for better or worse, whether you agree with them or not—America’s most important public intellectuals. Breyer and Kennedy’s remarks in March seem salient amid the current national debate over mass incarceration, but they’re not new arguments for either justice. Breyer told the subcommittee he has frequently criticized mandatory minimums before. Imagine if he had critiqued it for a national TV audience a decade ago. Imagine if he had been asked about it now.

The Oscar Hopefuls Gathering Early Buzz in Toronto

For a film director craving highbrow acclaim or status, the Toronto International Film Festival isn’t necessarily the most important date on the culture calendar. But in recent years, it’s become a valuable staging area for the winter Oscar season. At Toronto, the biggest film festival in the world, big-budget studio pictures and the year’s most-hyped indies jockey for press attention and for the chintzy-sounding People’s Choice Award—an incredibly reliable bellwether for award-winners. It’s not hard for a surprise crowd-pleaser to get anointed as a Best Picture favorite and then later actually win the golden statuette.

Related Story

No More Superheroes: A Fall Film Preview

The biggest debuts this year included Ridley Scott’s space thriller The Martian and Tom Hooper’s transgender-history drama The Danish Girl, but unlike previous festivals, no single film has managed to run away with the buzz. In 2008, Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire won the People’s Choice and then the Oscar, as did Tom Hooper’s The King’s Speech in 2010, as did Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave in 2013. But this year, as Katey Rich put it in Vanity Fair, critics are bemoaning “the lack of a five-star, shout-it-from-the-rooftops masterpiece.”

The most scrutinized premiere was The Martian, a hard sci-fi adaptation of a bestselling novel in which Matt Damon plays a NASA astronaut stranded on Mars waiting to be rescued by his fellow scientists on earth (played by a huge ensemble of stars). Scott, the director, is responsible for two of the most beloved sci-fi films of all time—Alien and Blade Runner—but Toronto critics expressed relief that The Martian didn’t turn out like his underwhelming Prometheus. Variety’s Peter Debruge praised the film’s “rigorous realism,” while The Hollywood Reporter’s Todd McCarthy lauded its surprising cheeriness, a rarity for the normally downbeat director, whose filmography includes Thelma & Louise, Gladiator, and Black Hawk Down.

It seems likely The Martian will become a commercial hit, but it’s harder to predict awards success for a genre thriller, no matter how intelligent. The Danish Girl, on the other hand, seems guaranteed to spark Oscar interest just for being a mainstream film that deals with transgender rights. It tells the story of Lili Elbe, the first-known recipient of gender-confirmation surgery. A swirl of controversy around the casting of Eddie Redmayne in the lead role has only attracted more press, but the film apparently strives above all to respect its subject, lending it the kind of “worthy but safe” vibe of many Oscar-nominated biopics. The emerging star Alicia Vikander, who made a splash in Ex Machina earlier this year, has also attracted raves in her role as Elbe’s supportive wife.

Though no film quite stands out as a clear favorite, several performances have been earmarked as standouts, including Johnny Depp’s transformation into the Irish mobster Whitey Bulger in Black Mass, which goes into wide release Friday. Along with Damon, Redmayne, and Vikander, the biggest draws have been Brie Larson, the lead in Lenny Abrahamson’s Room (an adaptation of Emma Donoghue’s novel); Idris Elba, who plays an African warlord in the upcoming Netflix film Beasts of No Nation; and Tom Hardy, whose role as both of the notorious Kray Twins stands out in Brian Helgeland’s gangster film Legend.

As the festival winds down, one other surprise critical hit has emerged—Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight, a true tale about Boston Globe investigative journalists digging into a major Catholic Church scandal—that features the meaty ensemble of Mark Ruffalo, Michael Keaton, John Slattery, and Rachel McAdams. Though the film isn’t the wide-screen epic affair of some of the festival’s most-publicized premieres, Time Out’s Dave Calhoun called it “a movie that’s both important and engrossing” and Vanity Fair’s Richard Lawson praised its sober, economical approach, avoiding sensationalism to tell “a knotty story with boundless intelligence, wit, and insight.” The film, barely noticed on the fall schedules before its festival debut, may end up being Toronto 2015’s surprise success.

The awards-season machine can be a depressing part of the film world, highlighting mainstream and worthy works at the expense of more radical approaches. But, at the very least, it stills prompts an industry increasingly dependent on worldwide grosses to fund small-scale work less guaranteed to turn a profit. Every year, some films seemingly designed to generate Oscar slobber succeed at their goal (plenty don’t), while deserving micro-budgeted efforts find acclaim against the odds. In that respect, this year at Toronto is no different.

Just How Bad Is the 2015 Fire Season?

Compassion fatigue and disaster fatigue are just as potent in the U.S. as they are with the refugee crisis in Europe. Each summer, it seems like the news fills up with headlines about enormous wildfires across the West, tearjerking anecdotes of residents who have lost their homes, and spectacular photos of firefighters and flames. Each year, the stories include new “worsts” and historical records. At some point, especially for those far away from the fires, it becomes hard to tell just how bad a given fire season is. So how does 2015 stack up? Does it just feel worse because it’s happening right now?

The truth is this year is among the worst in recent memory, according to statistics kept by the National Interagency Fire Center. Helpfully, the center tracks fires up to this point in the year going back a decade, so it’s easy to make an apples-to-apples comparison.

The number of fires is actually down in recent years—but look at the number of acres burned and the picture changes. More land has burned so far in 2015 than in the same period in any year in the past decade.

The staggering 8.8 million acres burned represents a serious reversal from earlier in the season. When Climate Desk checked in on fires in April, they found that 2015 had one of the lowest totals in a decade, lagging far behind 2006. Since then, massive fires, particularly in California, have closed the gap and then some.

That’s not unexpected. Even in the spring, officials were predicting an awful year for fires. California, which has received the most attention, is in a long and painful drought that has led the state government to take unprecedented water-conservation measures. But Washington and Oregon are also in the midst of droughts, and active fires have burned nearly three times as many acres in Washington as they have in California.

Droughts can be cyclical, and aren’t necessarily tied to climate change. But scientists note that the warming trend means that forests have lost moisture, so they’re more susceptible to fires when they come. Higher temperatures have also led to dwindling snowpack, so that dry conditions reach into increasingly higher altitudes. My colleague Alana Semuels recently reported from Alaska, where the state has been hit with record fires, even as it had to reroute the famous Iditarod race for lack of snow.

Meanwhile, there are increasingly urgent questions about the way the U.S. approaches fire management. Fighting fires can break natural cycles of burn and recovery, but as people move into potential burn areas, it’s harder for firefighters to make the case for standing back and letting the flames go. One result of this strategy is hotter and larger fires. Fire managers refer to anything larger than 100,000 acres as a “megafire,” and before 1995, there was an average of less than one per year. But that number has begun steadily climbing. At this moment, there are five active megafires.

In other words: Yes, those headlines every year about the growing danger from fires aren’t just fearmongering or a failure to contextualize numbers with recent history. The danger from wildfires really is larger now than it used to be. If there’s any good news, it’s that NIFC expects fire potential from central California north to decrease in October—but Southern California still faces an elevated risk of burning. It could be a hot and painful fall.

The Mindy Projection

[Small spoilers ahead.]

“The Mindy Project,” Mindy Kaling writes in her new book, Why Not Me?, “is most inspired by Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.” The show is a rom-com. Its male lead, Danny Castellano, is basically a Staten Island-raised version of Fitzwilliam Darcy. And while its female lead, Mindy Lahiri, is “much less like Elizabeth Bennet than she is a combination of Carrie Bradshaw and Eric Cartman,” the show also features miscommunication and confusion and mutual arrogance and mutual humblings and supporting characters both well-meaning and meddling, all of these things having the combined effect of preventing—or almost-preventing—the central couple from getting together.

With “getting together” meaning, in the Austenian sense, “getting married.”

Given all that, Kaling initially envisioned The Mindy Project, she writes, going something like this:

Boy meets Girl. Boy hates Girl. Girl is not that crazy about Boy either. Eventually Girl wears Boy down with friendliness. Boy and Girl become confidantes. Boy grows to love Girl but can’t express it. Boy and Girl get very close to marrying other boys and girls. Boy realizes he was being kind of dick. Girls realizes she was being judgmental and superficial. Boy and Girl have sex. Boy and Girl accidentally get pregnant. Boy and Girl love each other as best they can and live happily ever after.

It’s a formula that could easily become boring/frustrating/saccharine. It doesn’t, though. The Mindy Project manages to inject both heart and humor into its bare-bones, borrowed plot structure. The final scenes of last season’s finale, in particular—the last episode aired by Fox before The Mindy Project moved to Hulu for the current season—found Mindy and Danny, pregnant and in love, talking about getting engaged. Mindy wanted that. But Danny didn’t. Not because he didn’t love Mindy—not because he didn’t want to be with her, in the almost-Austenian way—but because, being both a child and a man of divorce, he was deeply suspicious of marriage.

Mindy empathized, but refused to compromise.

“It’s not weird to want your boyfriend to get down on one knee, and to meet your parents, and to get you a ring,” she told Danny, tearfully, sticking to her guns.

“Marriage means nothing!” he protested.

“It means something to me,” she replied.

The episode ended with Danny flying to India to meet Mindy’s parents, with him going to Mindy’s parents’ apartment building, with a door opening, and with … well, we didn’t know, really, what happened after that. The season ended, abruptly.

The newest episode of The Mindy Project combines that opening door with a Sliding one. Mindy, not sure where her boyfriend is and assuming the worst (“Why would Danny run away? When all I wanted was to get married? I mean, I’m pregnant with his child!”), murmurs angrily that “my life would be so much better if I’d just fallen in love with someone else.”

The Mindy Project manages to inject both heart and humor into its bare-bones, borrowed plot structure.Cue the dream-sequence-that-doubles-as-an-alternate-reality-exploration—one that is, she’ll later say, “like It’s a Wonderful Life,” except “in color” and “not boring.” Mindy finds herself waking up in a strange, beautiful bed. (“Where am I?” she wonders, at first. “Oh no, did I break into Mariah Carey’s penthouse and fall asleep again?”) It turns out that she is home—in a sprawling apartment with a view of Gramercy Park and an absurd variety of wall treatments—and married. Not to Danny, but to a guy named Matt (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), who is a producer for the Real Housewives franchise, and who has not only met Andy Cohen, but is best friends with him, and who is also an amazing cook, and who also got her an enormous engagement ring. Mindy still works as a doctor at Shulman & Associates; instead of founding her own fertility clinic, though, she has created, as a side gig, a company called “Delectable Desires” (which provides, Matt reminds her, “slutty girdles for the sexually active obese”).

Dream-Danny, Mindy soon learns, treats her with the distant, only vaguely affectionate disdain he treated her with when The Mindy Project first started. Dream-Danny is also dating Freida Pinto, whom he met at spin class when their “quads brushed,” erotically.

While all this is going on, in the “real” world Danny is in India, pretending to help Mindy’s parents arrange a marriage for her so he won’t have to tell them that he’s the one who got her pregnant. Morgan, being Morgan, finds a way to fly to India and inject himself into the proceedings. The Big Bang Theory’s Kunal Nayyar, thoroughly de-nerded for the role, guest-stars as a young widower who ends up being the team’s likeliest candidate for Mindy-marrying.

There is, it should go without saying, an extra-absurdist element to all of this. But there’s also a deep and very real anxiety—a very Austenian anxiety—at its core, which has to do with the basic truth that luck and fate are inextricably intertwined. There’s an element of chance, always, that determines the people we love, the people who in turn determine the courses of our lives. Mindy, had things gone very slightly differently for her, very well could have ended up with a reality-show producer who makes her croissant-based breakfast sandwiches and happily displays her South Park-themed pinball machine in their otherwise Adler-ized living room. Danny very well could have ended up with Freida Pinto.

But love has a way of conferring the luck with a sense of destiny. Being with him, Mindy tells Dream-Danny, was “what was meant to happen.” And “I don’t care if we’re not married,” she tells the real one, finally, when he comes back from India and interrupts her crazy dream. “I just want to be with you, okay?”

Luckily, he feels the same way.

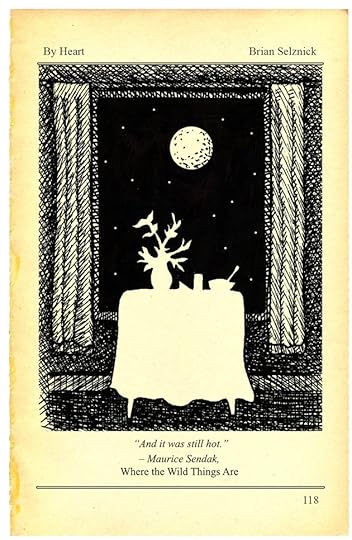

The Magic of Where the Wild Things Are

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

Doug McLean Brian Selznick, the author of The Marvels, never intended to make books for kids. Today, his ambitious, immersive picture books become New York Times bestsellers, but years ago, as a young Rhode Island School of Design graduate, Selznick tended to dismiss the entire genre. Then Where the Wild Things Are changed his life. In our conversation for this series, Selznick gave a brilliant close reading of Maurice Sendak’s classic, explaining how the subtle interplay between text and image enhances and deepens the story. Then, he shared how the book inspired a 15-year artistic exploration that culminated with The Invention of Hugo Cabret, Selznick’s Caldecott Medal-winning breakthrough.

Selznick’s books aren’t like anyone else’s: His 500-plus page epics alternate between illustrations and text, rarely featuring both at the same time. (In a 2012 profile for The Atlantic, I described how Selznick used the form—indebted equally to silent film and the “wild rumpus” section of Wild Things—to create new narrative possibilities.) His latest book, The Marvels, opens with 400 pages of mostly wordless illustration, chronicling 150 years of family history—all before the first chapter of prose. It’s a story about loss working its way across generations, as a young runaway looks toward the past to find a home.

Selznick is also the author of Wonderstruck and many other illustrated books; The Invention of Hugo Cabret was adapted by Martin Scorsese into an Oscar-winning film, Hugo. He lives in Brooklyn and San Diego, and spoke to me by phone.

Brian Selznick: Early on, I never thought I’d want to illustrate children’s books. In high school, I associated them with cute, talking animals—and when people suggested I might grow up to illustrate books for kids, as they often did, I always felt vaguely insulted. Later, when I went to art school, there were many famous illustrators on the faculty, but I never took classes with them. Even Maurice Sendak visited, but I didn’t go to hear him speak. I had never read his work as a child, and I wasn’t sophisticated enough to think about what else the form might be able to do.

I went through college thinking I was going to be a set designer for the theatre. But after graduation, I ended up getting a job at Eeyore’s Books for Children on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. There, my life took a very different direction than I had anticipated. It was at Eeyore’s that I first sat down with Where the Wild Things Are, and fell completely in love with it. The key to everything I wanted to do, it turned out, was between the covers of that book.

I felt drawn to Where the Wild Things Are even before I opened it. The title is so intriguing, and the cover is beautiful. The book is a great size, with nice matte paper on the jacket, and it feels good in your hands. It is, of course, a great fantasy story: A boy goes to this place where the wild things are, conquers them, becomes king of them, and then makes the decision to leave and go home to the place where he’s loved best. I found myself deeply affected by the way the page-turns work, by the way the illustrations themselves change in size and shape as the story progresses.

On that first reading, I think I intuitively understood the way the book’s layout and its story play off each other, two equally important parts—how the structure of the book is in many ways the same thing as the story being told.

If you go back and look at Where the Wild Things Are, you’ll notice that every element of the book’s design helps to tell the story of this little boy named Max. The very first drawing, which depicts Max misbehaving in his house, is just a little tiny rectangle on a big sea of white space. The adjacent text says:

The night Max wore his wolf suit and made mischief of one kind

As you turn the page, the illustration is another small rectangle, with text that says:

and another

But as he is sent to his room, and as his room begins to transform into the forest around him, the drawings themselves begin to take up more space. Each time you turn the page, they grow and grow. By the time he is in the land of the wild things, the text has been pushed to the edge of the page. And when the wild rumpus begins—the famous, wordless section where Max and the wild things revel in the woods—there is no more white space, and no more text. The drawings themselves have taken over and are bleeding over all four sides of the open book.

It’s up to you, the reader, to move through the wild rumpus at your own pace. Then, when you come out of it, the text reappears—and Max makes his decision to head back home. As he sails back in and out of a day, and through a week, and in and out of a year, the images become progressively smaller again. But you’ll notice that, when he finally arrives, something has changed. The drawing of his room—which, when we last left it, had been a small rectangle in a sea of white—now takes over half the book. It’s a full bleed on half of the spread. His home is larger now. Max has been enlarged by the adventures he’s been on, by what he’s experienced in the land of the wild things. The physical space that he occupies in the book has grown.

Then, most profoundly, as you turn the page, the drawings disappear altogether. For the first time, we have no drawings on the spread. There is just a single line, referring to the dinner that Max’s mother has left for him:

and it was still hot.

It’s that un-illustrated last page, with that simple last line, that I think most affects us. Because one of the brilliant things about Maurice Sendak as an illustrator is he knows what not to illustrate. You should never illustrate poetry, he used to say—referring, I think, to instances when an illustration might have a reductive effect on the text. So, you don’t see Max happily eating his hot soup. You don’t see his mother with her arm around him. By not illustrating that line, we, the reader, are asked to understand and see that line for ourselves. It trusts us—whether we’re three years old or a grown-up looking back—to understand its meaning and bring our own emotions and associations to it.

For me, it means I love you. For me, it means you’re safe. It means all the things that Max’s mother, the parent, is feeling towards the child—no matter how angry the child gets, or how frustrated. No matter how much Max might lash out, or have a tantrum, or chase his dog with a fork. Ultimately, the child is still loved. All of that is encapsulated in those un-illustrated five final words: And it was still hot.

Illustrating a children’s book, I realized, isn’t just drawing a picture that goes with the story on each page. It’s thinking about the entirety of the book as part of the experience of the story. All of the structural elements that go into Where the Wild Things Are are not necessarily meant to be noticed. But we feel them. And it’s the fact that they’re there that makes the book as powerful and everlasting as it is.

I spent many years illustrating books after that, trying to figure out new ways to draw pictures. I did nonfiction books, shorter stories, novels, some of which I wrote myself, always trying to keep in mind how I might make the illustrations specific to each project. It took about 15 years of exploration before I was able to make a book like The Invention of Hugo Cabret—the roots of which, in many ways, you can see in the wild rumpus section of Where the Wild Things Are.

Illustrating a children’s book, I realized, isn’t just drawing a picture that goes with the story on each page.When I started work on Hugo I wrote the story with no pictures—I was just writing it as a novella. I wanted the illustrations to do something different, but I wasn’t sure what. Since the story was going to be about the history of cinema, I started thinking about how movies tell their stories. I thought about the moment I love in The Wizard of Oz, where Dorothy opens her door from the black-and-white world of Kansas into this technicolor dreamscape. And I doubled back to books like Where the Wild Things Are, where the pictures are intrinsic to the telling of the story—where each page-turn has the potential to be as exciting and dramatic as Dorothy opening her door into the full-color world of Oz.

I began to wonder if the mechanics of a picture book could hold up over 500 pages in a novel for older readers. So I went back to my novella, removing text that could be replaced with illustrations: descriptive scenes, action, things that we could watch unfold. I began to experiment with the idea that a single story could go back and forth between language and pictures without using them at the same time. It all goes back, in a way, to that division in Where the Wild Things Are: the wordless wild rumpus section, and the un-illustrated “and it was still hot.” That is where Hugo and Wonderstuck and The Marvels really got their start—though it was 15 years of watering the ground before those seeds could sprout.

As I wrote Hugo, I wasn’t always sure my instincts were correct. It was a weird story, after all: a boy who lives in the walls of a train station and is obsessed with French silent movies. Though I loved those elements, there was nothing about the story that indicated anybody would want to read it. Nobody watches silent movies. And kids, certainly, don’t watch French silent movies.

During this time, I turned to Maurice for advice. He helped me understand that the most important thing is to tell your story and to be true to the things that are most important to you. There was a certain fearlessness with Maurice and his work, especially in terms of what you might think is appropriate or inappropriate for children. Spike Jonze made a wonderful short documentary about Maurice, Tell Them Anything You Want, when he was working on his movie version of Where the Wild Things Are. In this wonderful series of interviews in his home, Maurice talks about the fact that children are smart, and children are brave, and children understand much more than you think they do. If you’re telling them something that’s true, they can handle it. They’re very often several steps ahead.

Essentially the experience of being a child is unchanged: It’s hard to be a kid, and it’s scary to be a kid, and it’s exciting.So, when I’m writing, I don’t think about writing for children—even though I’m very proud of the fact that I’m a writer and illustrator of children’s books. Other than the fact that I know I’m probably not going to use any cursing, and there’s probably not going to be a sex scene, I’m just writing the stories that I want to write, and I’m writing the characters who interest me. It’s less about the fact that it’s for kids than it is about trying to write the most satisfying version of the story that is coming to me over the three or four years that it takes me to make these books.

Often, that means thinking about things I loved when I was 10—magic, and movies, and monsters. These motifs, in various forms, are still the things that most interest me. And the feeling kids have when they’re trying to figure out their families, the people at school, and the world all around. When everything is a mystery, and everything is strange, and everything seems somewhat incomprehensible.

Maurice’s own childhood was so present in his working life. I remember going to his house when he was working on Bumble-Ardy, one of the last books he published. He was drawing this crazy parade on a piece of paper, all these figures marching across his desk. I’d point to the faces in the crowd—these weird, grotesque faces—and I would say, Maurice, where did this face come from? Where did that face come from? He told me they were resurfacing from things he had seen as a kid. It was like the person he was when he was just a scared, vulnerable, sickly child in Brooklyn had stayed with him. His art was a way to work through those fears, and was a constant source of comfort.

If I learned anything from Maurice, it was very much that it’s okay: The form is a place to work through those fears. The things that scared you as a kid are still scaring children. The world is very different from when Maurice was a kid, which is very different from when I was a kid, which is very different from the world of children today. But essentially the experience of being a child is unchanged: It’s hard to be a kid, and it’s scary to be a kid, and it’s exciting. All of that can be expressed in this incredible art form of children’s books.

The Bastard Executioner: A Study in Violence

Why do people kill and torture? Sadism, fanaticism, social contagion, hatred, anger, honor codes, survival—all reasons seen in the real world, explained in horrifying headlines and cool-eyed histories and some of the more perceptive works of art and literature in history. In other kinds of fictional works, though, the motivations for mayhem are bizarre, removed, ornate—plot contrivances allow for bloody entertainment that prompts only minor twinges of queasy recognition from the audience.

Related Story

The Most Disturbing Thing About Game of Thrones' Most Disturbing Scene

FX’s new series The Bastard Executioner offers an extreme version of this phenomenon, needing a twisty-and-turny two-hour debut to establish what could turn out to be the most reliable killing-and-maiming machine TV has ever seen. Set in 14th-century Wales, its hero is a “punisher,” someone whose job it is to flay and de-fingernail and behead those who’ve crossed his lordly employers. The twist—not enacted till the end of the premiere, though not hidden in FX’s ads for the show—is that he’s a reluctant punisher, an undercover one, living out a version of The Prince and the Pauper where instead of faking erudition he must fake a knack for making people scream.

To arrive at this premise, the show brings together not one but three of the most classic tropes about damaged men who must cause violence. Vengeance required by extravagant harm befalling women and/or children in his care? A struggle against oppression from unambigiously evil institutions? A mysterious Chosen One prophecy? All of this, plus the actor Lee Jones’s surprisingly kindly face and affect, combines so that when his character Wilkin Brattle performs his first public execution, it’s pure payoff: We’re to marvel at the grim weight of his mission, the nifty swordsmanship he uses, and the gore.

The show, from Sons of Anarchy creator Kurt Sutter, isn’t oblivious to the psychic toll of violence, but nor is it shy about milking it for righteous, video-gamey thrills. The first episode opens with a dream sequence, featuring super-saturated colors and metal music and Brattle in battle. Eventually, a naked angel-girl and a CGI demon show up—it’s the most bitchin’ telegraphing of PTSD you’re likely to see this on prestige TV this week. Another, more experienced punisher on the show has an even worse case of soul damage from his career; he abuses his wife, his son, and himself, ritualistically scarring his body at night. And when innocents are killed—as happens a lot—the show lingers on the tragedy of the situation, though with so much fake blood and entrails that it’s natural to wonder whether the camera is trying to tap into sadness or voyeurism.

The show is not oblivious to the psychic toll of violence, but nor is it shy about milking it for righteous, video-game-y thrill.Perhaps this is the point—to indulge in the primal allure of violence but also its horrible consequences. With its historical-medieval setting, the show can be defended for portraying harsh truths in much the same way that Game of Thrones can; even more than on HBO’s show, The Bastard Executioner wallows in nasty period details—castle latrines, consumption, socially acceptable sheep buggery. But on Thrones, each flaring of brutality feels like the result of a Rube Goldberg-like allegory about cause and effect. In Executioner, the bad-guy/good-guy divide is less ambiguous, and the murder-to-purpose calculations more disproportionate; passion, not realpolitik, drives a lot of the plot. This might actually be truer to life’s messiness than the careful, morally weighted storytelling of Thrones. But it also feels baser, crasser, cheaper.

Or perhaps that’s just because of the quality of the show more generally. It isn't all bloodletting; there’s dialogue in faux-old-timey lingo laying out palace intrigue and explorations of Middle Ages Christianity. But with visibly second-tier production values, The Bastard Executioner feels a bit more like people playing dress up than the best works in its genre should. The only characters to not fall into cliched dichotomies of rag-tag rebels and power-mad gentry are the women—a mystic of unclear purpose and unclear accent, played by Katey Sagal, and a demure but calculating baroness, played with quiet intelligence by Flora Spencer-Longhurst. Outside of them, the intrigue factor is low; while Thrones’s first episode offered a buffet of engaging personalities, here, you’re not that curious about anyone’s backstories. For now, the entertainment value of the show is one of the oldest and darkest there is.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower