Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 304

November 6, 2015

The Long, Slow Death of the Keystone XL Pipeline

Updated on November 6, 2015, 12:44 p.m.

President Obama finally killed the Keystone XL pipeline on Friday, waiting until the last drop of suspense had drained from a debate that pitted environmentalists against champions of economic development and domestic oil production.

“The pipeline would not make a meaningful, long-term contribution to our economy,” Obama said. “So if Congress is serious about wanting to create jobs, this was not the way to do it.”

By the time the president made the announcement with Secretary of State John Kerry and Vice President Joe Biden standing by his side, the administration’s almost comically-long deliberation over the proposal—some seven years—overshadowed the pipeline itself, which would have stretched nearly 1,200 miles from Canada to the Gulf Coast. Republicans and centrist Democrats long held up Keystone as a job-creator that would be a boon to the nation’s ailing economy, but that argument began to lose steam as the economy strengthened in recent years.

Obama himself had cited studies finding that Keystone would create few permanent jobs, and as if to underscore his dim view of the economic argument, he rejected the project just hours after the Labor Department reported that U.S. employers had created 271,000 jobs in October and that the unemployment rate had dropped to 5 percent, a seven-year low.

On Friday, the president said that Kerry had met with him that morning and told him that the department’s review had concluded that construction of the pipeline “would not serve the national interests of the United States.”

“I agree with that decision,” Obama said. The decision is a blow to Canada, which had lobbied hard for the U.S. to approve the pipeline. The president said Canada’s new prime minister, Justin Trudeau, had expressed “disappointment” when the two spoke on Friday.

As the State Department proceeded with its long review of the proposal, the president had been gradually signaling his sympathy for the argument of environmentalists, who said the tar-sands pipeline would undermine the legacy of a president committed to combatting climate change. Still, he repeatedly rejected calls to speed up the review process. When Republicans made a Keystone bill their top priority upon winning full control of Congress earlier this year, Obama used his veto pen for just the third time in his presidency. Yet the administration’s delay in deciding on the project became too much even for Hillary Clinton, who announced her opposition in September when she said she could wait for Obama no longer.

In explaining his decision Friday, the president bemoaned that the Keystone had taken on “an overinflated role” in the nation’s politics. “It became a symbol too often used as a campaign cudgel by both parties rather than a serious policy matter,” he said. “All of this obscured the fact that this pipeline would neither be a silver bullet for the economy, as was promised by some, nor the express lane to climate disaster claimed by others.”

Obama argued that, in effect, the passage of time had showed that the economy could improve without the modest benefits offered by the pipeline. He cited the sterling jobs numbers and the fact that gas prices had dropped significantly in the last year—refuting another early claim by Keystone proponents. Finally, Obama said that approval of the pipeline would undercut a central premise of his administration’s economic agenda—that the U.S. could take aggressive action to combat climate change and protect the environment without sacrificing jobs and growth.

Republicans, of course, were unmoved. “This decision isn’t surprising, but it is sickening,” said the new House speaker, Paul Ryan.

By rejecting this pipeline, the president is rejecting tens of thousands of good-paying jobs. He is rejecting our largest trading partner and energy supplier. He is rejecting the will of the American people and a bipartisan majority of the Congress. If the president wants to spend the rest of his time in office catering to special interests, that’s his choice to make. But it’s just wrong.

Earlier this week, TransCanada, the company seeking to build the $8 billion pipeline, asked the State Department to suspend its review of the project. Critics suspected the request was not made because TransCanada was giving up on the pipeline, delaying the decision until after the 2016 presidential election, when a Republican victor might approve it. But the State Department rejected the plea, probably because its decision had already been made.

There Won't Be a Keystone XL Pipeline

President Obama has rejected the Keystone XL pipeline, killing the long-stalled project to bring oil from the Canadian tar sands to Texas.

“The State Department has decided that the Keystone XL pipeline would not serve the national interests of the United States,” Obama said. “I agree.”

The announcement, during which the president was flanked by John Kerry, his secretary of state, and Vice President Joe Biden, is the culmination of years of debate—much of it rancorous—over the Canadian company TransCanada’s proposed 1,661-mile pipeline. On Thursday, the State Department rejected TransCanada’s request to put a review of the project on hold until a dispute in Nebraska over the project’s proposed route was resolved.

The State Department, which had final say because the project crossed an international border, had been reviewing the pipeline for more than six years, working to determine whether it was in the national interest. Congressional Republicans had tried—unsuccessfully—this year to circumvent that process and grant the project a permit immediately. Friday’s decision effectively kills all those efforts.

Environmentalists, some landowners in Nebraska, and liberal Democrats had long opposed the project, arguing the negative environmental impact outweighed any positive contribution. But supporters of the project—including politicians from both parties, some unions, and energy companies—said the pipeline would create jobs and reduce U.S. dependence of oil from the Middle East. (You can read about the debate here.) Both those arguments have been eroded since the project was first proposed: The price of oil is at multi-year lows amid a supply glut, and the U.S. is now one of its top producers. Add to those factors Friday’s jobs numbers: The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the U.S. added 271,000 jobs last month —far higher than 180,000 figure estimated by economists. The unemployment rate held steady at 5 percent.

Obama’s announcement is likely to have an impact on the presidential race. Hillary Clinton, the Democratic front-runner, had already come out against it, as has her main rival, Bernie Sanders. The Republican candidates support the project.

Spotlight: A Sober Tale of Journalism Done Right

For much of its running time, Spotlight holds its audience at arm’s length. Its plot follows one of the most upsetting topics conceivable: Child abuse in the Catholic Church, and institutional efforts to cover up the crimes. Tom McCarthy’s film follows investigative reporters at The Boston Globe who helped uncover the story in 2002, and recreates their painstaking process with great attention to detail—the journalists gather information, pester sources, and take notes on first-hand accounts of molestation, but only at the very end of the film does the impact of it all fully hit them, and the viewer.

Related Story

Truth: A Terrible, Terrible Movie About Journalism

Like any good reporting job, Spotlight slowly builds momentum from nothing, gathering disparate bits of information into an emotional juggernaut of a story. But unlike most directors making films about journalists, McCarthy doesn’t indulge in the usual Hollywood claptrap to cast them as flawed superheroes. The central cast isn’t the motley crew of self-destructive drunks and grandstanders you’d usually see—this is a film about the methodical process of reporting, not the stirring heroism behind it, and at the end of the film, it’s the story itself, not the journalists’ personal achievements, that stands triumphant.

McCarthy has never been a visual wizard, and Spotlight lacks much flair in that regard. The film takes place largely in the stodgy offices of The Globe’s investigative team, and in coffee shops and lawyer’s offices around the city. But the movie returns the director and co-writer (he scripted with Josh Singer) to his greatest area of expertise: characters whose emotional arcs play out almost entirely under the surface. His best films—The Station Agent, The Visitor, and Win Win—told quietly moving stories without leaning on dramatic outbursts. McCarthy’s most recent release, the more whimsical The Cobbler (starring Adam Sandler), was a catastrophe, but Spotlight returns him to solid ground.

The film boasts a fine ensemble: Michael Keaton plays Walter Robinson, the Spotlight team’s venerable editor, who commands the reporters Michael Rezendes (Mark Ruffalo), Sacha Pfeiffer (Rachel McAdams), and Matt Carroll (Brian d’Arcy James) under the eye of their managing editor Ben Bradlee Jr. (John Slattery) and The Globe’s new editor-in-chief Marty Baron (Liev Schreiber), who’s pushed them toward the unenviable task of investigating the diocese in a largely Catholic city.

Each character feels emblematic of a certain recognizable type of journalist without resorting to caricature. There’s Ruffalo’s live-wire agitator who seems disinterested in having a personal life, and Slattery’s hand-wringing deputy advising caution at every turn, and McAdams’s rigorous interviewer who exudes a warmth that gets strangers to spill their darkest stories to her. Keaton is the star, though, continuing the career renaissance that arguably began with his bravura work in last year’s Birdman. There was little subtlety to his last role, but as Robinson, Keaton projects his understated torment over the fact that his team could have tackled the story sooner but subconsciously avoided it.

This is a film about the methodical process of reporting, not the heroism behind it.But this isn’t a film that coasts on the work of its actors, who provide few moments of bombast. Nor is it a stern lecture on the evils of the Church, or the institutional powers that kept the voices of the abused silent for so many years, though it hardly shies away from those subjects. Spotlight instead shows how such a well-orchestrated secret can be uncovered: not through the will of one editor or reporter, but through the combined efforts of a well-run, well-staffed journalistic organ not beholden to moneyed interests, and with enough will to push past any political or social pressures.

Which might make the film sound like a manifesto, but Spotlight’s lack of polemic makes the message that much clearer. Ironically, on the fifth season of HBO’s The Wire, McCarthy (who also acts from time to time) played a fictional Baltimore Sun reporter who won a Pulitzer Prize by exaggerating his reporting on various city issues. The show’s creator David Simon seemed to be railing against perceived enemies of real journalism by creating this straw-man character, and the story consequently fell flat. But by quietly celebrating the work of The Globe’s reporters, McCarthy makes a far more consequential argument for the value of smart reporting and robust local newspapers.

There is perhaps a strange timewarp quality to Spotlight: It presents a Boston Globe recently acquired by The New York Times, not yet sweating layoffs and buyouts, as it and so many papers nationwide have weathered in recent years. But McCarthy does well not to turn his story into a larger rant on the state of modern journalism. The journalists’ work speaks for itself, and the film succeeds by letting it stand on those merits.

Sweet Relief: A Strong October Jobs Report

After three consecutive months of disappointing jobs reports, October finally delivered the strong numbers economists had been hoping for.

The report from the Labor Department shows that the unemployment rate fell to 5 percent, and the economy added 271,000 jobs in October—beating expectations of 180,000. That’s the strongest showing in 2015 thus far.

Hiring surged in professional and business services, health care, retail trade, food services, and drinking places, and construction sectors. The September jobs-added numbers have been revised down to 137,000 from 142,000, while August’s numbers have been revised up—from 136,000 to 153,000. In the past three months, job gains have averaged 187,000 per month.

By all measures, the October jobs report quiets the fears that the U.S. economy is slowing. And October’s strong performance has reignited speculation that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates at its December meeting.

The Federal Reserve has been looking for a strong jobs report before making what would be the first interest-rate hike in nearly a decade. Federal Reserve chairwoman Janet Yellen has mentioned that achieving full employment post-Great Recession has been difficult, though the Fed considers an unemployment rate of 5.0 to 5.2 percent to be full employment, a feat that was achieved over the summer. Despite this, many economists believe there’s still room for growth since the labor-participation rate remains at 62.4 percent, the lowest level since 1977.

Last week, Yellen testified before the Financial Services Committee of the House of Representatives. She noted that the U.S. economy was performing well, and that if the good news kept coming, “December would be a live possibility.”

The Fallout From the Russian Plane Crash

Updated on November 6 at 9:33 a.m.

President Vladimir Putin has agreed to suspend all flights to Egypt while an investigation determines what caused a Russian passenger jet to crash last weekend in the Sinai, a Kremlin spokesman said Friday.

The decision came following a recommendation earlier Friday by Aleksandr Bortnikov, the head of the FSB, Russia’s internal-security service. Dmitry Peskov, the Kremlin spokesman, said Putin also ordered the safe return of Russians in Egypt and cooperation with Egyptian authorities on air-traffic security, Russia Today, the state-run broadcaster, reported.

Egypt is a popular tourist destination for many Russians, and it was the Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh that many Russian tourists were leaving last Saturday when Metrojet Flight 9268 crashed shortly after takeoff. A claim of responsibility by an affiliate of the Islamic State was quickly dismissed while Egyptian and Russian officials began an investigation into the crash.

But that didn’t stop speculation into what downed the plane—speculation that only intensified after Britain suspended flights from Sharm el-Sheikh, citing fears of terrorism. Prime Minister David Cameron said it was “more likely that not” that terrorism was behind the crash—comments echoed by President Obama.

Egypt and Russia reacted angrily to the speculation, saying it was premature while an investigation was ongoing, but Russia’s decision Friday to suspend its flights to all of Egypt are likely to only increase speculation about what downed Flight 9268.

Updated on November 6 at 9:07 a.m.

Here’s the latest:

BREAKING: Russian President Putin has agreed to a recommendation to suspend all Russian flights to Egypt.

— The Associated Press (@AP) November 6, 2015

This is a developing story and will be updated based on new information.

Updated on November 6 at 9:00 a.m.

The head of the FSB, Russia’s internal security service, is recommending that all Russian flights to Egypt be halted while an investigation determined what caused a Russian passenger jet to crash last weekend, killing 224 people.

“As long as we haven’t established the causes of the incident, I consider it appropriate to suspend the flights of Russian aircraft to Egypt,” FSB director Aleksandr Bortnikov told a meeting of the Russian Anti-Terror Committee on Friday. “This primarily applies to the tourist flow.”

The British airline EasyJet says two of its flights have left the Egyptian Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh with 379 passengers, while Egyptian authorities aren’t allowing seven others to operate. EasyJet and other British airlines are trying to return an estimated 19,000 Britons home after the U.K. suspended outbound flights from the resort city following last weekend’s crash of a Russian plane.

Egyptian and Russian investigators say it’s too early to conclusively say what caused the crash, but Western officials, including President Obama and British Prime Minister David Cameron, say it looks increasingly likely the plane was downed by terrorism. All 224 people on board were killed.

U.K. officials said they were working with their Egyptian counterparts to ensure the scheduled flights leave.

“Our aim is to get as many people home as soon as possible,” John Casson, the British ambassador to Egypt, said at Sharm el-Sheikh airport.

It’s unclear why Egyptian authorities prevented the eight Easyjet flights from operating—Egyptian officials say the Sharm el-Sheikh airport was being overwhelmed—but Britain’s quick attribution of a cause—terrorism—for the Russian plane crash angered both Egypt and Russia. Both countries said the diagnosis was premature since an investigation was ongoing.

But concerns about terrorism could hurt the Egyptian economy, which relies heavily on tourism to places such as Sharm el-Sheikh for revenue. Russia was also angered because of its involvement in the Syrian civil war, in which it is carrying out airstrikes on behalf of President Bashar al-Assad against rebel group, including the Islamic State. It was an Islamic State affiliate that initially claimed responsibility for the Russian crash—a claim that was quickly dismissed by Russia and Egypt.

Western officials have publicly, and through leaks, suggested terrorism downed Metrojet Flight 9268. On Friday, the BBC reported that investigators believe a bomb was placed in the plane’s hold prior to takeoff. Cameron, the British prime minister, said Thursday it was “more likely than not” the plane was downed by terrorism; and Obama, in an interview Thursday with Seattle’s KIRO, said while there is an ongoing investigation, “I think there is a possibility that there was a bomb on board. And we are taking that very seriously.”

American Qu’ran Makes a Sacred Text Familiar

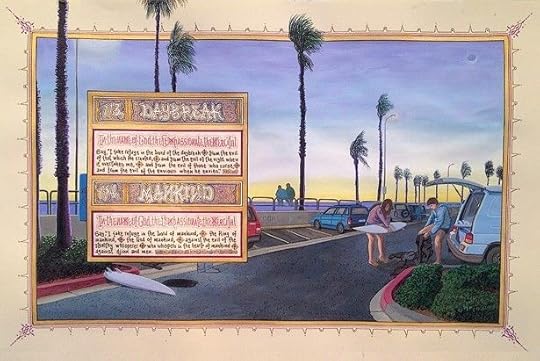

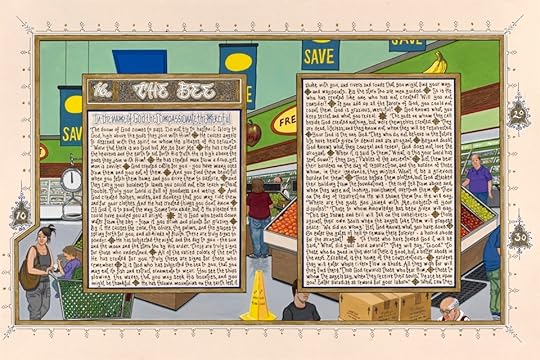

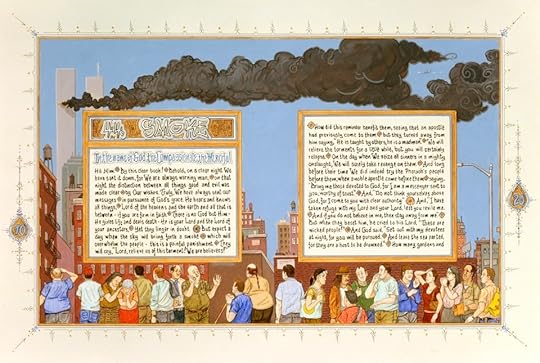

Sandow Birk spent the last nine years creating an illuminated manuscript of the Koran in English. He didn’t do it for religious reasons—he’s not a Muslim. Instead, the American artist wanted to undercut cultural prejudices about one of the world’s most important religious texts, which Americans tend to associate with the Middle East and with violent extremists like ISIS. (The situation hasn’t been helped by negative portrayals of Muslims in the media.) Birk’s American Qur’an, which was exhibited in several gallery shows before being released this week in its entirety as a book, places translated passages next to cartoon-like illustrations, connecting the work with some of the most quotidian of American experiences: shooting hoops after school, fixing a flat tire, burying a loved one.

“You could make the argument that the Koran is the most important book in the world right now, and it has been for the last 20 years,” Birk says. “And for Americans to not know what it says is a mistake.” While Christianity is seen as a universal message, he says, despite its Middle Eastern origins, Christian Americans don’t see Islam in the same way.

The urge to unpack this paradox ignited Birk’s interest in the Koran. His version can’t be considered authentic because it’s not in Arabic; but his main goal was to create a cultural, not religious, text. He hand-transcribed the entire book using a calligraphy inspired by graffiti from his neighborhood in Los Angeles. But he kept the traditional formatting and structure, including margin size, ink color, page headings, and the medallions marking each verse. For the illustrations themselves, he flouts one of the fundamental laws of Islamic art: no representations of humans or animals. Instead, his illustrations feature an array of people who reflect the diversity of America.

Sandow Birk

Sandow Birk For Birk, maintaining harmony between his own drawings and the passages was one of the most vital aspects of the project. To do that, he had to focus on the words themselves. He found that many of the Koran’s stories and morals resonated with his knowledge of the Bible, which he studied in art history class.

Sandow Birk

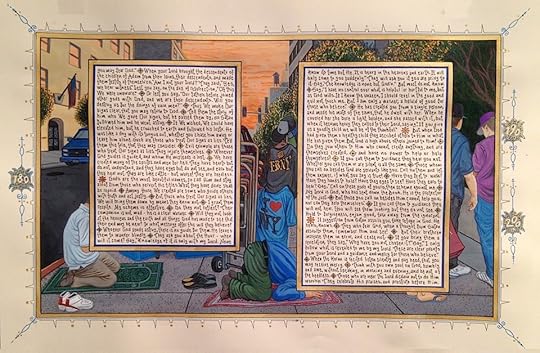

Sandow Birk As the Yale professor Zareena Grewal writes in an essay that opens American Qur’an, Birk is driven in part by the question, “Why can’t Islam be an American religion?” In one illustration, two Muslim men kneel on prayer rugs on the street in New York next to a vendor selling “I Love NY” t-shirts. Their faces are hidden, their ethnicities ambiguous. With this scene, Birk asks his audience to disentangle stereotypes of racial and religious identity. As Grewal notes, “Birk insists that we cannot know who is or is not Muslim just by looking at the people who populate the American Qur’an; the same holds true for the people who populate America.”

Sandow Birk

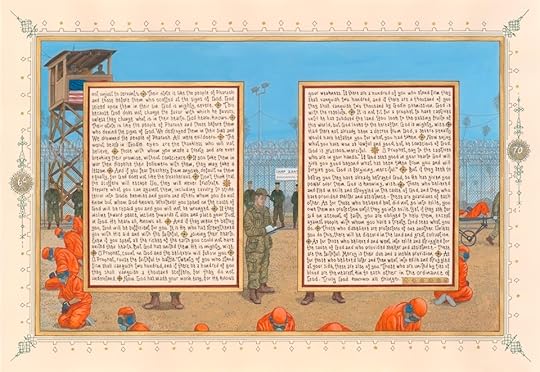

Sandow Birk Other illustrations comment on American foreign policy. Birk paired parts of the Koran that discuss preparing for war—passages often cited as proof Islam is violent—with scenes of Americans invading Iraq or of prisoners detained in Guantanamo Bay. In doing so, Birk wanted American readers to recognize the double standard implicit in the assumption that Islam condones fighting more than any other religion.

Sandow Birk

Sandow Birk  Sandow Birk

Sandow Birk Another particularly haunting image depicts the Twin Towers on 9/11—Birk acknowledged that the project wouldn’t be complete if he didn’t address the attacks. The chapter, titled “Smoke,” includes a passage about “a day when the sky will bring forth a smoke which will overwhelm the people,” and focuses on the reactions of people on the ground. The scene, one of his earliest drawings, stretches across two pages.

Sandow Birk

Sandow Birk “I’ve been more hesitant and self-doubting about this project than anything else I’ve ever done,” Birk explained to The New York Times in 2009. “I think the consequences of it being misunderstood are extreme.” Now, however, he’s less worried because the project has been generally well-received in the Muslim American community, especially among teenagers and young adults. He recalled how a group of Muslims was looking at his work in a gallery during mid-day prayer time, so they prayed on the floor beside his illustrations.

Still, some Muslim religious leaders have spoken out against the project, including Mohammad Qureshi of the Islamic Center of Southern California, who refused to visit the California gallery where Birk was showing several pages of American Qur’an in 2009. “The Koran is accessible the way it is,” Qureshi told Art Daily. “It's been accessible for 1,400 years.” Usman Madha, the director of public relations at the King Fahad Mosque in Culver City, told The New York Times in a critique of Birk’s work, “There is no such thing as an American Koran, or European Koran, or Asian Koran.”

But for Birk, the project is more than just a conversation starter or political statement. It fundamentally questions the role of a painter in the 21st century: to create something that is meaningful, relevant, and thought-provoking. “The idea of making an entire illuminated manuscript like the monks did in the Middle Ages—it’s something that only an artist can do,” he says. “My occupation is 500 years old: All my neighbors work in Hollywood, and here I am transcribing ancient texts. I’m very aware of the irony of that.”

Spectre: Bond Doesn’t Need an Origin Story

“The dead are alive.”

The words that flash across the screen at the beginning of Spectre have two distinct sets of meaning, one of which is apparent immediately and one of which will become so soon enough. The first is literal: As the words fade, the scene opens in Mexico City on the Day of the Dead.

The streets throng with crowds of dapper skeletons and chthonian floats. The camera finds its way to one elegant couple—the man’s skull mask only accentuates his air of intensity—and it follows them down the avenue. And into their hotel. And into the elevator. And into their room. And then, following a not-entirely-unexpected reveal, it follows the man out the window and onto the rooftops.

Long tracking shots may be a tad oversold in the wake of Birdman and season one of True Detective, but this one is a dazzler. Indeed, the entire pre-title sequence of Spectre—which also includes fisticuffs in a wildly spiraling helicopter over a crowded square—is magnificent, perhaps the best in the entire 24-film history of the franchise. At its conclusion, I turned to the friend seated next to me and whispered, “I could leave the theater happy right now.”

From there, the movie leaps from London to Rome to the Austrian Alps to Tangier and the Sahara, the plot trundling on along two parallel tracks which inevitably will bend to intersect. Abroad, a rogue James Bond (Daniel Craig) is trying to track down information about a diabolic global crime syndicate, Spectre, and its mysterious leader (Christoph Waltz). Back home, M (Ralph Fiennes), Q (Ben Whishaw), and Moneypenny (Naomie Harris) must contend with a smarmy young bureaucrat who’s overseeing the launch of a panoptically comprehensive new global surveillance system. About all you need to know about this character is that he is played by the actor Andrew Scott. I mean fine, launch your dangerous new technology that will make all human privacy a thing of the past. But for God’s sake, don’t put Moriarty in charge of it. (And yes, this is exactly the same plot as Captain America: The Winter Soldier, right down to many of the particulars, including a snazzy, Triskelion-ish intelligence HQ on the bank of the Thames.)

Sam Mendes, who directed the previous installment of the franchise, Skyfall, returns for an encore and once again gives the proceedings an upscale gloss. But while there are plenty of pleasures to be found scattered across Spectre’s exorbitant two-and-a-half-hour running time—this is, after all, a Bond film starring Daniel Craig—the movie loses momentum at each stop and is flagging by its conclusion. Moreover, it makes a number of substantial narrative missteps, falling into some old bad habits and developing a few new ones.

Begin with the second meaning of “the dead are alive,” which is advertised as early as the title sequence. There, amid the customary naked ladies—here ickily accoutered in octopi—flash images of previous Bond villains Le Chiffre (Casino Royale) and Silva (Skyfall), along with Bond’s deceased love, Vesper Lynd, and deceased boss, the previous M (Judi Dench). In essence, Spectre is an elaborate retcon job, a bid to turn the Craig movies into a unified trilogy (yes, technically a tetralogy; bear with me). This is achieved principally by revealing that Spectre was secretly (and rather murkily) behind all the evil plots that took place in the earlier films. Or, as Waltz’s character explains to Bond late in the movie, “It’s always been me, James, the author of all your pain.”

The backward references to previous films are almost innumerable, and act as an accumulating drag on the current one. Dench even has a cameo in one of those “watch this video only after my death” scenes. Given the extent of the nostalgia-fest, it’s amusing that the film’s producers seem eager to have us forget about Craig’s less-successful second outing as Bond, Quantum of Solace. Among the literally dozens of references to Le Chiffre, Silva, Mr. White, Lynd, and M, they left in—perhaps accidentally?—just one glancing mention of “Greene,” Quantum’s villain.

This tying together of Craig’s Bond oeuvre—by the end, literally: as in, with string—is a decidedly poor idea, and its logic doesn’t hold up to even the most cursory scrutiny. But this is, I fear, a consequence of our current heyday of novel series, serialized television, and cinematic “universes.” It’s no longer sufficient for a movie to have a “plot.” Now it must have an “arc”—or rather, multiple arcs both within and spanning sequential films and even interrelated series. I tremble for the day when some enterprising young exec has the bright idea of cross-pollinating Bond with fellow Sony property Spider-Man.

Bond is best left a cypher, beyond the realm of causal psychology.Related to this too-tidy interweaving of the last few films is the decision by Bond’s custodians to give 007 an elaborate, tragic-orphan backstory. This intent was suggested in Skyfall, but Spectre takes it a great deal further. This movie’s villain is inserted into that tale, too, such that he is the author not only of Bond’s spyhood pain, but of his boyhood pain as well. Here I must voice a strenuous dissent: Bond is not Batman; he does not need an origin story. Ian Fleming himself described 007 as “an anonymous, blunt instrument wielded by a government department.” (Or as my friend and colleague James Parker memorably characterized him, “a bleak circuit of appetites, sensations, and prejudices, driven by a mechanical imperative called ‘duty.’”) He is, in any case, best left a cypher, beyond the realm of causal psychology.

Even as Spectre offers dubious new wrinkles to the franchise, it unlearns some of the crucial lessons of its recent success. One of the chief delights of the Casino Royale reboot was how aggressively it pushed back at the tropes that had been weighing down Bond movies for decades: the endless womanizing, the gadget-laden cars, the secret lairs. As Le Chiffre told 007 before smashing his groin with a knotted rope, “I never understood all these elaborate tortures.” Spectre backslides on virtually every one of these fronts: the women, the super-car, the villain’s secret hideout in an arid crater (!), and his endless monologuing as he subjects Bond to the most elaborate torture since Auric Goldfinger threatened him with a Lasik circumcision.

Are there enough good moments to make up for these lapses? Yes, there are: a dizzying car chase in Rome, a Spectre meeting that falls just this side of camp (it’s like an Eyes Wide Shut party in which everyone keeps their clothes on), an alpine chase in an aircraft fuselage, that astonishing opening sequence. Dave Bautista is a solid heir to the brotherhood of Bond heavies such as Oddjob, Jaws, and Robert Shaw’s underrated peroxide assassin, Donald “Red” Grant. Fiennes does a creditable job of trying to fill Dench’s fundamentally unfillable shoes. And Monica Bellucci is beguiling as a beautiful widow. (Her: “Can’t you see I’m grieving?” Bond: “No.”) By contrast, the movie’s principal love interest, played by Lea Seydoux, alas makes almost no impression at all.

But ultimately, of course, it all comes back to Craig himself. This is likely his last outing as Bond—part of the reason, no doubt, for all the wrapping-up—and the question of whether he or Sean Connery most owned the role can now begin to unfold in earnest. But regardless of who next buttons the tux and holsters the Walther, the lesson of Spectre is a simple one: Let Bond be Bond and the mission be the mission, without the need for connective arcs and tragic backstories. Next time, let the dead stay dead.

The Messy, Improbable History of SPECTRE

Ian Fleming was afraid the Cold War would end too soon.

While serving as a British Naval Intelligence officer during the Second World War, he’d begun to think about writing a spy novel. By the end of the 1950s, his James Bond series was a huge success. Fleming met with several collaborators, chiefly the filmmaker Kevin McClory and the playwright Jack Whittingham, to brainstorm an original screenplay based on the exploits of his hard-living creation. But movies take a long time, and the conspirators worried that relations between the West and the East could improve so much in the interim that a scenario pitting Bond against Soviet spies like the ones he battled in Fleming’s early books would be old hat before the film’s prints were dry.

Their future-proof solution was SPECTRE, an organization that used Space Age, acronym-generating technology to ally itself not with any political or economic system, but to assorted malign abstractions. Decoded, the name stood for SPecial Executive for Counterintelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, and Extortion. While the legal battle over which creator had dreamt up what would outlive them all, one thing was clear: No one could think of a suitably menacing word that began with the letter “P.”

That the 24th “official” James Bond film is called Spectre feels like a promise kept. The last scene of 2012’s Skyfall, the most lucrative and critically admired entry in the always profitable, suddenly venerable franchise, teased a restoration. Six years earlier, Casino Royale had given the (re)boot to decades of accumulated shark tanks and volcano lairs and disposable women with names like Pussy Galore and Holly Goodhead and Plenty O’Toole. In their place was the closest that action-adventure cinema ever gets to a character study. Daniel Craig’s leaner, greener, deadlier 007 was a “blunt instrument,” in the withering description of his boss, Judi Dench’s M. But the 38-year-old actor’s command of the role turned out to eclipse even Sean Connery’s.

In Spectre, Craig seems more Connery-like—fearless, entitled, and inscrutable—than ever. Meanwhile, the series’s brief detour into something approximating realism is concluded. SPECTRE is no longer an acronym, or if it is, no one troubles themselves to spell it out. The organization has its tentacles in phony pharmaceuticals and human trafficking, it’s revealed, but it doesn’t declare allegiance to abstraction, because under the regime of the director Sam Mendes and the writer John Logan (both returning from Skyfall), the Bond film franchise is now more than ever an abstraction unto itself. If Casino Royale was recognizably an adaptation of an Ian Fleming novel, Spectre is more like an attempt to film the Bond franchise’s Wikipedia page.

Its reintroduction of SPECTRE-the-organization is a miscalculation based on two things: A market-driven determination that Bond films should be more like the tradition-embracing Skyfall (worldwide gross $1.1 billion) than Casino Royale ($599 million), and the 2013 conclusion of a legal battle that had (mostly) kept the evil organization out of the Bond pictures for 40 years. No one had really missed it, and the filmmakers had already solved the problems of its absence in an unloved entry that took its clunker of a title from an unrelated Fleming short story: 2008’s Quantum of Solace. Reviving SPECTRE now, while playing to the unquenchable nostalgia of Bond devotees, only clarifies how ridiculous the institution has always been.

* * *

Skyfall, Craig’s third outing in the role, is set much later in Bond’s career than his first pair of appearances. Early on in the movie, MI6 believes that Bond’s been killed by friendly fire, and he’s in no rush to let the agency know he’s survived. When he finally reports for duty (by breaking into M’s flat, a fun callback to Casino Royale), he’s out-of-sorts, out-of-shape, and addicted not just to booze, but pills. Still, M covers for him, and by the end of Skyfall’s deflating, rather too Home Alone-inspired final act, nearly all the familiar characters and tropes that Casino Royale had stripped away have regenerated. Once again, Bond is receiving equipment and derision from Q, flirting with Miss Moneypenny, and—for the first time since 1989’s grim Licence to Kill—taking orders from a man. That this new M is played by Ralph Fiennes is small compensation for Dench’s departure after a seven-picture tour of duty, but still a promising development.

Even so, the keepers of the Bond flame—Barbara Broccoli, the daughter of the original series producer Albert “Cubby” Broccoli, and her half-brother, Michael G. Wilson—didn’t have all the materials to fully return Bond to his Beatles Invasion-era primacy until two years ago, after Skyfall had become the highest-grossing film of all time in Britain. Late in 2013, a series of lawsuits that had ricocheted around courts in the U.K. and the U.S. for half a century was finally settled. This at last allowed 007’s greatest (and most oft-parodied) nemesis, the cat-stroking Ernst Stavro Blofeld, and his organization, SPECTRE, to return.

If Casino Royale was an adaptation of an Ian Fleming novel, Spectre is more like an attempt to film the Bond franchise’s Wikipedia page.The new movie’s long-con promotional campaign has played coy about the fact that the character played by the Academy Award two-timer Christoph Waltz, one Franz Oberhauser, is in fact—spoiler alert—Blofeld, even if putting a shot of Waltz in a nehru jacket in the trailer was a clear provocation.

Waltz is more than equal to the task of contributing yet another colorful and inexplicably polite rogue to 007’s gallery, of course. Craig’s Bond already had two films behind him by 2009, when Waltz’s performance as the Nazi Colonel Hans Landa in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds snagged him a Best Supporting Actor Oscar and substantially elevated his profile. So why the filmmakers chose to have him play a goofy character now best remembered as the inspiration for Mike Myers’s Dr. Evil in Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery is a mystery beyond even the code-cracking resources of MI6.

* * *

Blofeld and SPECTRE entered the world with the publication of Thunderball, Fleming’s eighth Bond novel, in 1961. Confusingly, Fleming based the book on the unproduced screenplay he’d hashed out with McClory and Whittingham—without crediting his collaborators. McClory sued and eventually got an out-of-court settlement that included the film rights to Thunderball.

It was no small prize. Because the rights to Casino Royale, Fleming’s first Bond adventure, were unavailable thanks to a little-remembered, 48-minute TV version from 1954, Cubby Broccoli and his partner Harry Saltzman had eyed Thunderball as their first Bond feature. But the legal fracas—plus the fact that Thunderball’s grand scale, including extensive underwater scenes, would make it too pricey for their first at-bat—pointed them toward the more modest Dr. No instead.

By the time they circled back around to Thunderball three years later, Bond was the biggest thing in movies, and money was no object. They gave McClory sole “produced by” credit on Thunderball, and licensed his rights—which had been generously interpreted to apply not just to the characters and concepts in whose creation McClory had participated, but to James Bond and all the other Fleming-created characters in the novel, too—for a full decade, just to be safe. Surely the Bond fad would run its course by 1975.

MGM Studios

MGM Studios SPECTRE was a part of the Bond films from the beginning, 1962’s Dr. No, wherein Joseph Wiseman’s titular antagonist revealed himself to be a member of the organization intent on disrupting a U.S. space launch with a giant nuclear reactor. After helpfully breaking down his organization’s secret recipe—Counterintelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, Extortion—he proclaims these ingredients to be “the four great cornerstones of power.” As if the acronym weren’t swell enough, in 1965’s Thunderball, SPECTRE associates wear conspicuous matching rings bearing the organization’s sigil: an octopus. (In any fiction where the spy didn’t make a big deal of introducing himself, in public places, by his real name, twice, this might perhaps seem indiscreet.)

Despite its love of logo-branded bling and high-ceilinged conference rooms with incinerator pits, SPECTRE operates in the shadows, playing the Cold War superpowers against one another. “World domination, the same old dream,” sighs Sean Connery when the claw-handed Dr. No volunteers his motives, as every one of 007’s opponents would be weirdly obliged to do.

In its sequel, From Russia With Love, Blofeld makes his film debut, though his face remains out-of-frame. He likens the U.S. and the Soviet Union to the Siamese fighting fish he keeps in a jar on his desk, who brawl until they’re both too spent to repel a patient third party. But SPECTRE doesn’t appear in the novels Dr. No or From Russia With Love at all. The cabal was a much bigger presence in the first decade of Bond films (1962-71) than in the books from which they had been very freely adapted.

While Eon Productions, the company Broccoli and Saltzman had co-founded when they got into the James Bond business, had intended from the start to build a spy-flick franchise, their thinking was shockingly short-sighted by contemporary standards. Franchises barely existed in the 1960s. 1934’s The Thin Man had spawned five sequels, and Universal’s monster movies shared a loose fictional universe that even permitted the occasional crossover, like 1948’s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. But the consistency of casting and fidelity to the source material that fans demand of, say, The Hunger Games pictures or the modern adaptations of born-in-the-60s Marvel superheroes were a nonissue right until the 21st century.

Eon filmed Fleming’s novels out of order and never thought twice about it, even when this made the continuity of the movies impossible to reconcile. And while Bernard Lee’s M, Desmond Llewelyn’s Q, and Lois Maxwell’s Moneypenny were all regular players, other recurring roles, like Bond’s C.I.A. buddy Felix Leiter, were recast willy-nilly.

But sidekicks are one thing. Nemeses are another.

* * *

Blofeld appeared in four consecutive films between 1965 and 1971, played by a different actor each time. The last of these, Diamonds Are Forever—the film for which Connery was expensively coaxed back after breaking his contract four years earlier—belatedly explains Blofeld’s ever-changing appearance by saying the character regularly received plastic surgery and also had underlings surgically altered to resemble him, to confuse would-be assassins, a detail also present in Fleming’s books.

The movie offers no such reason for why Connery’s Bond had turned into the Australian model George Lazenby for one movie, then reverted to his thicker, grayer, more Scottish shape. (It didn’t help that Connery couldn’t be bothered to hide his boredom in the role this time, though given Diamonds’s awful script, you couldn’t blame him.)

Audiences’ willingness to suspend disbelief allows for casting changes, of course. But it still makes no sense that Blofeld doesn’t recognize Bond (Lazenby) in 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, when 007 infiltrates his Swiss “allergy clinic” (bioweapons plant) in the guise of a genealogist investigating Blofeld’s claim of noble parentage. They were face-to-face just one movie ago, but Blofeld (Telly Savalas) behaves as though he and Bond are meeting for the first time. Is it because Bond’s disguise included an uncharacteristic ensemble of frilly shirt, kilt and glasses? It couldn’t be because the actors playing both Bond and Blofeld in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service were making their first-and-only appearances.

MGM Studios

MGM Studios Just to show how little Broccoli and Saltzman sweated the small stuff—like casting—Diamonds’s Blofeld is played by Charles Gray, who had previously appeared in You Only Live Twice as one of Bond’s allies. (Donald Pleasance served as that film’s Blofeld.) They didn’t bother to change Gray’s look before reusing him; with his beady gray eyes and fist-sized cleft chin, he looks more like a mannequin than a man anyway. And his hilariously polite and unthreatening Blofeld was the least of the film’s problems.

Once the Thunderball option expired in the mid ’70s, McClory again busied himself trying to get his own Bond movie going. This would eventually result in 1983’s Never Say Never Again, a remake of Thunderball that stands outside the already-loose canon of Eon 007 films despite the presence of 53-year-old Connery in his seventh and final outing as Bond. (His public swearing-off of the role inspired the title, a suggestion of his wife.) Though it grossed a little less than Octopussy, the Moore-starring 007 flick released all of four months earlier, it’s a more enjoyable movie. It featured Max von Sydow as Blofeld, marking the character’s only appearance in a Bond movie between 1971 and today.

Except one.

In what could only be interpreted as a very public middle finger to McClory, Broccoli resurrected the unnamed-but-clearly-recognizable Blofeld for the pre-title sequence of 1981’s For Your Eyes Only. The film opens with Moore’s Bond visiting the grave of his wife Tracy, who was married to him for just minutes before being gunned down by Blofeld and his henchwoman Irma Bunt in the shocking final scene of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Bond is summoned to a helicopter, which a bald, nehru jacket-wearing, wheelchair-confined fiend hijacks via remote control, intending to crash it with 007 inside. After enduring some impressively staged near-misses with various buildings and/or the ground, Bond seizes control of the helicopter, then skewers Blofeld’s wheelchair on one of its landing skids and climbs into the air.

While For Your Eyes Only is remembered (if it’s remembered) as one of the less ostentatious Bonds, this bit is as silly as anything in Austin Powers. Blofeld’s final words in the series take the form of a bizarrely specific plea for mercy:

BLOFELD: We can do a deal! I’ll buy you a delicatessen! In stainless steel!

BOND (reaching through the cockpit window to pat what is clearly a dummy’s bald head): All right, keep your hair on.

According to the co-screenwriter and executive producer Michael G. Wilson, it was Cubby Broccoli himself who came up with the line. The director John Glen, who would helm all five Bond pictures made in the 1980s, thought it was just too good not to use. Unswayed by this invitation to enter the food-service industry, Bond drops Blofeld’s wheelchair and its occupant down a chimney of the Beckton Gas Works.

* * *

McClory made a few more attempts to get back into the spy game before he died in 2006. In 1997, Sony Pictures announced they were going into business with him not only on yet another Thunderball remake—to be called Warhead 2000—but an entire Bond series, to compete with the Eon films then enjoying a resurgence with Pierce Brosnan as 007. MGM, the studio releasing the Eon movies, took Sony to court and won, but Sony laughed last: It led a consortium that acquired MGM in 2004. The current crop of Craig-starring films have all borne Sony’s logo.

The least well-received of them, Quantum of Solace, introduced its own shadowy cabal in lieu of SPECTRE, whose rights were still the subject of legal wrangling. Its plan was modest by the standards of Bond films, maybe even plausible: Its members were going to assist a Bolivian coup d’etat to further their long-term aim of controlling the world’s water supply. Its name, the Quantum Group, sounded more like an investment firm co-founded by Bono than an outfit that would electrocute operatives caught skimming in front of their colleagues.

By bringing back SPECTRE, the Bond people have once again reduced their hero to an idea, a silhouette in a tuxedo.Largely reviled upon its release seven years ago, Quantum has aged well, especially if you watch it with a fresh memory of Casino Royale. (They’re really two halves of a 410-minute movie, the only time two Bond pictures have been so closely tied.) In its most memorable scene, the villainous conspirators confer in plain sight, using earpieces, at an outdoor performance of Tosca. Bond does what he can to disrupt the meeting and identify its participants, but his efforts are largely futile—Quantum has cut a deal with the C.I.A. That development keeps the movie rooted in the dirty world of 21st-century espionage, while the rest flies in the face of the rationale often given for Bond’s 1960s ubiquity: Women wanted him, men wanted to be him. Quantum’s Bond was not a man whose life would inspire envy.

But he was recognizably a man, one in whose fate audiences could feel invested. By bringing back his abstraction-defined nemeses, the Bond people have once again reduced him to an idea, a silhouette in a tuxedo. And Spectre, for all its attempts to keep up with the Marvel movies and the Missions: Impossible and all of the other big-budget franchises Bond wrought, remains—forgive the pun—a period piece.

November 5, 2015

What Happened in Kunduz?

On October 3, the U.S. bombed a hospital run by Doctors Without Borders, (MSF), the Nobel Peace Prize-winning humanitarian group, in Kunduz, Afghanistan, killing at least 30 people. In the aftermath of the bombing, MSF called for a never-before-used mechanism of the Geneva Conventions to investigate the strike, and General John Campbell, the senior-most U.S. commander in Afghanistan, said the “hospital was mistakenly struck”—an apparent evolution of the U.S. position on what happened that day in Kunduz.

The bombing came amid the backdrop of the Taliban’s capture—since reversed—of Kunduz. It was the Taliban’s biggest prize since the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan ousted the militant group from power. The fighting was bloody and the civilian toll high. Many of the injured—civilian, Afghan military, and Taliban—were treated at MSF’s Kunduz hospital.

At a news conference in Kabul on Thursday, Christopher Stokes, MSF’s general director, said it’s “quite hard to understand and believe” the hospital was mistakenly hit. The group released an initial internal review of the strike that pointed out that U.S. and allied militaries were given the GPS coordinates of the hospital, and though Taliban members were treated at the facility, there were no weapons inside—in keeping with the organization’s rules. The report makes for chilling reading. One excerpt: “Patients burned in their beds, medical staff were decapitated and lost limbs, and others were shot by the circling AC-130 gunship while fleeing the burning building.” In its report, MSF said:

View noteThe report detailed the week prior to the U.S. attack, starting September 28, when the MSF team launched a mass-casualty plan to receive an expected large number of people wounded in the fighting between the Taliban and Afghan forces.

The next day, September 29, MSF says it informed the U.S. and others of its exact GPS locations because fighting had intensified.

View noteOn Wednesday, September 30, MSF says it received two Taliban patients, who “appeared to have had higher rank.” They were brought in by several combatants, and there were regular inquiries about their medical condition “in order to accelerate treatment for rapid discharge.”

The following day, October 1, the group says it received a query:

View note View noteOn October 2, the night of the airstrikes, two MSF flags were placed atop the facility, which was one of the few buildings in Kunduz still to have electricity. A nightly security check, conducted shortly after midnight, found the area “calm.” And, the report appeared to dismiss Afghan government claims that the hospital complex was being used by the Taliban in their fight.

View note View noteThe attacks began 2 a.m. and 2:08 a.m. on October 3, the MSF report said. At the time, the hospital was treating 105 people. Between three and four were government combatants, MSF said. About 20 were wounded Taliban. Also present: 140 MSF national and nine international staff, and one delegate from the International Committee for the Red Cross. The airstrikes continued for a little more than one hour, and ended between 3 a.m. and 3:15 a.m., the MSF report said.

Here’s a log of calls made by MSF during the airstrikes:

View noteAnd here’s what MSF says about the attack itself:

View note View note View noteIn Washington on Thursday, Captain Jeff Davis, a Pentagon spokesman, said MSF had shared its report with the military.

“We have worked closely with MSF to determine the facts” surrounding the attack, he said, adding the U.S. would continue to work closely with the group to identify both those killed and wounded “so that we can conclude our investigations and proceed with follow-on actions to include condolence payments.”

You can read the full MSF report here.

A Century of Hot-Dog Production Comes to an End in Madison, Wisconsin

In 1883, Oscar Mayer opened a meat shop in Chicago where he made sausages and ham with his brother. They were quickly successful, a fact attributed to both the excellence of the Mayer brothers’s sausages and the growing ranks of German-American immigrants eager to eat them. By 1919, the Mayers’ meat business had gotten so big that the company bought a slaughtering plant in Madison, Wisconsin, in order to source raw materials. By 1955, sales were in the millions and the company moved its headquarters from Chicago to Madison.

Oscar Mayer (the company, not the man) was still being run by Mayers until it was sold to General Foods Corporation in 1981. Eight years later, the company was merged with Kraft at the order of its parent company, Philip Morris. On Thursday, Kraft Heinz Food announced that it would close down the Oscar Mayer headquarters and plant in Madison, after 96 years. The news, though somewhat expected, has been hitting Madison residents hard. Madison’s mayor Paul Soglin estimated that the economic impact will be at the cost of “hundreds of millions of dollars."

The Oscar Mayer closure is part of a bigger Kraft Heinz downsizing plan to save $1.5 billion in the next two years. The company is shuttering plants in California, Maryland, New York, Wisconsin, and Ontario; all told, an estimated 2,600 jobs will be eliminated. Since Heinz acquired Kraft Foods in July (in an estimated $45-billion deal), the resulting gigantic company has been expected to consolidate its production factories and corporate staff. The best guess has been that this “new era” for Kraft Heinz will involve layoffs: In August, 2,500 workers in Kraft’s North American operations—including 700 corporate staff—were let go. Including what was called for in Thursday’s announcement, the company has reached its expected target, after shedding 10 percent of its 46,000 workers during restructuring.

The backdrop for all these changes is that Americans are becoming wary of processed foods. One report found that the market shares of packaged-food companies have been dropping by billions of dollars as consumers drift towards organic and “natural” offerings. For Oscar Mayer in particular, it doesn’t help that recent studies have linked processed meats to premature death and cancer.

But Americans still love hot dogs, consuming close to a billion packages a year, and summer barbecues and sports venues continue to be responsible for massive sales numbers. Around the world, demand is even looking up. The hot dog is definitely sticking around, but whether Oscar Mayer will be able to capture some of that growth will depend on whether it’ll stick to its classic branding, for international consumers who want classic, “American-style” food, or try to conform to America’s new food preferences.

In Photos: An Oscar Mayer Ending

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower