Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 251

January 19, 2016

The Promise of Flawed Characters

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

Doug McLean Flannery O’Connor’s short stories are famously harrowing. But Paul Lisicky, the author of The Narrow Door, says they’re much more than little, mean-spirited torment chambers (and not just because she’s funny). In his essay for this series, he looks closely at “Revelation,” in which a narrow-minded woman responds to public humiliation with surprising generosity. In this, Lisicky sees O’Connor’s vision emerge: The author subjects her characters to humiliation, betrayal, and violence to move them beyond their limitations, giving them the chance to emerge better from the wreckage of what they once were.

Related Story

How Fiction Can Survive in a Distracted World

The Narrow Door is Lisicky’s ode to two loved ones who left him, for very different reasons: About a year after a best friend lost her fight against cancer, his then-husband fell in love with someone else. Lisicky admits that as a memoirist, the temptation is to “turn darkness into light”; especially when writing about death, we tend to burnish painful memories until they shine, trying to offer something redemptive from the ashes. As in O’Connor’s writing, pain here offers an opportunity—it’s a chance to avoid the easy outs of sentimentality and false comfort, and to speak honestly about two difficult kinds of love, two complicated forms of hurt.

Paul Lisicky is also the author of the memoir Famous Builder and the novels Lawnboy and The Burning House. He teaches graduate writing at the University of Rutgers-Camden.

Paul Lisicky: I didn’t have to train myself to love Flannery O’Connor back when I first encountered her work in a creative-writing workshop. She wasn’t an acquired taste, such as Jane Bowles or Virginia Woolf, writers whom I came to love after several tries. Instantly I got O’Connor’s irreverence, her vitality, her play, her infatuation with human absurdity: snobbery, complacency—all of it. She was a writer who sounded like she was having fun. Bleak fun, to be sure. I could just picture her cracking herself up in front of the typewriter.

And yet the fun never felt easy or slight. I sensed that the work was written by a pretty grave person, someone who didn’t take human foibles lightly. She believed that actions mattered, had consequence. The fun here was never for the sake of an easy laugh. The fun was poised over an abyss, or under a thunderhead—it was hard to know for sure.

The first story I read of hers was “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” in which a family confronts a serial killer on a road trip to Florida. As a young writer I was riveted by its division into two halves: the first broadly comic, the second outright devastating, as each member of the family is shot, one by one by one. In workshops I’d been taught to value control and consistency. So much of what was praised in class seemed to be in sync with some imaginary command to strictness, as if characters weren’t allowed to be messy, chaotic creatures on the page. Weren’t we just reinforcing the social order with all these rules? Why weren’t we questioning them? But O’Connor’s story violated all that. It unleashed some anarchy—part God, part Devil—and made a new kind of story. Sure, it had the look of a linear story but it also managed to demolish such a story. Her example gave me permission to be bolder on the page, though it would take me years to make use of that permission.

I loved “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” for its ability to shake me into my bones—try reading the whole thing aloud sometime and you’ll hear exactly what I mean. But the story that really got to me was “Revelation.” Its effect might not be as dramatic as “A Good Man”—after all, no one is murdered—but a different kind of violence takes place. Here, a 47-year-old woman is humiliated by a young, college-educated woman in front of strangers.

It’s so easy to see O’Connor’s stories as little punishment machines that intend to flatten the characters until they behave as they’re supposed to.The bulk of the story transpires in a doctor’s waiting room, in which the central character, Ruby Turpin, accompanies her laconic husband, Claude, to his doctor’s appointment. She’s one of those people who’s uncomfortable with silence, terrified of self-examination, though she doesn’t yet know that about herself. She talks and talks and talks and talks and talks. She needs to be the center of attention and makes sure that happens by addressing everyone in the room, enfolding them into her little monarchy. But she isn’t exactly interested in making connections with others. The scene is about all about her desire to perform a certain version of herself: respectable, quick to laugh, grateful, blessed by Jesus for her “good disposition.” The small space contains a cross-section of 1960s small-town Georgia society: a “leathery, old woman,” in a cotton print dress; a mother with “snuff-stained lips” and her little boy; a “stylish, pleasant” lady; and her scowling daughter, Mary Grace, head buried in a textbook titled Human Development.

Most of the people in the waiting room are unfazed by the racist, cringeworthy things coming out of Ruby’s mouth. Maybe they’ve all heard it before; it’s been in the air and Ruby is simply playing her part. But it’s different for Mary Grace. She’s been away to college and now she’s stuck at home, trapped in what she now realizes is a brutal and provincial backwater. Ruby certainly represents everything she loathes about the place and fears for herself. Will Mary Grace become Ruby one day? Well, maybe home is powerful enough to do that do a person.

Maybe it’s the raw fear of that that prompts her to throw that heavy textbook at Ruby’s forehead.

The doctor is called in. Mary Grace is on the floor; a syringe slides into her arm. The room goes quiet, while Ruby sits frozen in her chair.

There was no doubt in her mind that the girl did know her, know her in some intense and personal way, beyond time and place and condition. “What you got to say to me?” she asked hoarsely and held her breath, waiting, as for a revelation.

The girl raised her head. Her gaze locked with Mrs. Turpin’s. “Go back to hell where you came from, you old wart hog,” she whispered. Her voice was low but clear. Her eyes burned for a moment as if she saw with pleasure that her message had struck its target.

For many readers, the story pivots on one single line of dialogue. In the long, steady aftermath of this eruption, Ruby looks out from high spot over her pasture, her cotton field, the “dark green dusty wood” beyond. “Who do you think you are?” she yells to a silent, indifferent God. An outrageous question, especially coming from the mouth of a self-professed Christian. The audacity of it would be hilarious if Ruby weren’t in the deepest turmoil, which she seems to have experienced bodily, all the way down into her flesh. Words have sliced through her, and everything she’s ever understood about herself has been carved up, within full sight of spectators.

But the description I keep coming back to takes place several paragraphs later than that. It’s funny that you can live with a story for years and not take in an image so central to its vision. It reverberates with the authority of a painting and practically has a life of its own, outside the narrative. It could be a little story all by itself, standing up on its own hind legs.

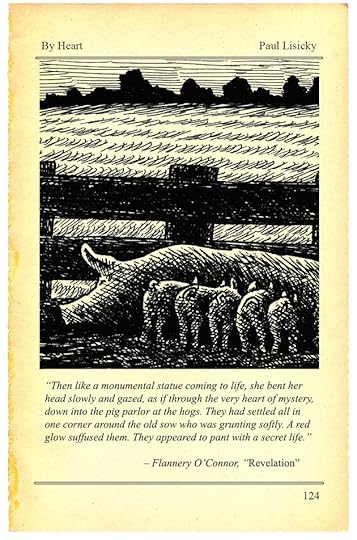

Then like a monumental statue coming to life, she bent her head slowly and gazed, as if through the very heart of mystery, down into the pig parlor at the hogs. They had settled all in one corner around the old sow who was grunting softly. A red glow suffused them. They appeared to pant with a secret life.

Up until this point, pigs stand as a metaphor to Ruby. Though she defends her hogs to the snuff-stained woman (“our hogs are not dirty and they don’t stink”), they’re still livestock. They’re still creatures who need to be hosed down. So it’s no surprise that Ruby would be shocked to be called a warthog; the shaming of it hurts far more than the physical attack. We already know some details about Ruby’s appearance—her little black eyes, her “very large” presence, which made the already small waiting room “even smaller”—but this comparison ends up overriding everything we’ve imagined. We now picture her with stray hairs on her face, wide nostrils, little bumps.

And yet Ruby changes in this passage. Her perceptions become active, personal, dynamic. For a fleeting moment, the pigs aren’t simply a mirror for herself. She’s seeing the pigs, as, well, pigs. They’re beyond metaphor. They aren’t clouded by the expected perceptions of them. They don’t need to be hosed down. And aren’t they a little beautiful, these pigs, leaning into one another, musical, grunting softly? A mother beside her children, safe, tight, in a contained space. And that glow about them, not just any glow, but suffused with red.

A narrative, when it’s really alive, will always disturb you when you’re there to seek comfort.It’s ironic that once Ruby sees the pigs as pigs, the pigs seem to move outside space and time. The story is quiet about this second transformation: to do anything more than that would be to break the spell. They’re at the center of the mystery. They’re creatures of another consciousness, beyond language, transcending our capacity to name and understand. They pant not just with life, but with secret life. And that word seems to mean everything here. Secrecy is something to treasure: inexhaustible, vast, and larger than ourselves.

This awful Ruby, whom we’ve been so quick to judge and make fun of, has confounded us again.

It’s so easy to simplify O’Connor, to see the stories as little punishment machines that intend to flatten the characters until they behave as they’re supposed to. Even sophisticated readers are prone to missing out on all the nuances in the work. The aim of these stories is certainly satirical, but that’s only part of the plan. Her characters always have the capacity to morph, not just once but many times, and that’s the lesson I take into myself: into my own writing, and into what I value about the work of other writers who matter to me. That people, no matter how inert they seem to be, contain the capacity to surprise us, to change.

Growth doesn’t happen without destruction—that one too. To miss out on that fact is to miss out on everything. Yes, O’Connor destroys some of her characters—subjects them to humiliation, degradation, violence. But maybe that’s because she understands human stubbornness, how we cling to our limitations until events of great force alter us. Maybe this attitude stems from her Christian vision—of a savior made holy through the horrors of crucifixion—or from the plight of her own tormented body, tortured by illness for much of her too-short life. In any case, O’Connor shatters her characters so they can see.

If Ruby Turpin stayed rooted in her horribleness, the story would be small and mean, a minor curiosity, not really worthy of our extended consideration. Instead we have something riskier and more volatile. O’Connor’s stories seem to start out small, realist, and regional, but it’s a fake-out: She knows that, ultimately, she’ll shake her characters to the core, and in the process challenge us. A narrative, when it’s really alive, will always disturb you when you’re there to seek comfort, and sing in two contrary voices when you just want to hear a single, pure melody. But it is impossible not to be lifted by such a strange and beautiful animal. Lifted and destroyed.

The Fate of Obama's Immigration Plan

The U.S. Supreme Court announced Tuesday that it would consider a legal challenge to President Obama’s immigration plan, setting up a decision on one of the president’s most extensive executive actions just months before he leaves office.

The Court will decide whether Obama’s program intended to shield millions of undocumented immigrants from deportation, announced in November 2014, can be implemented across the country. Texas and 25 other states led by Republican governors quickly filed a lawsuit against the unilateral actions, calling them unconstitutional and accusing the president of sidestepping Congress.

Since then, federal courts several times have blocked the program from moving forward. In February 2015, a federal judge in Texas entered an injunction shutting down the program. The U.S Justice Department appealed that decision, but the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans upheld the ruling last November.

The program, known as Deferred Action for Parental Accountability, or DAPA, would allow nearly 4.3 million immigrant parents of U.S. citizens and permanent residents to register with the government and begin working legally without the threat of deportation. Obama’s action also expanded the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, to provide the same protections to people who were brought to the United States from other countries as children and raised there.

The case will be heard in April, in the throes of the presidential primary season. Democratic candidates have vowed to defend or expand the president’s actions, while Republican candidates have promised to end protections for undocumented immigrants.

A decision is expected in June. If the Court rules in favor of the actions, the Obama administration would have seven months to implement the policy before the end of Obama’s term next January.

January 18, 2016

What Led American Ships Into Iranian Waters?

The U.S. military has released its first official account of Iran’s capture and release of 10 American sailors whose vessels entered Iranian waters in the Persian Gulf last week.

U.S. Central Command, or CENTCOM, on Monday provided a timeline of the events, but did not say how the two U.S. Navy boats ended up in foreign waters on their journey from Kuwait to Bahrain in a routine exercise. The sailors are currently in “good health,” CENTCOM said.

CENTCOM said the small boats stopped in the Gulf because of a “mechanical issue in a diesel engine” in one of the vessels. “This stop occurred in Iranian territorial waters, although it’s not clear the crew was aware of their exact location,” the statement said.

The two riverine command boats departed Kuwait at 9:23 a.m. GMT on January 12, the statement said. They were scheduled to stop and refuel alongside the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Monomoy at about 2 p.m. But at approximately 2:10 p.m., Navy command received a report that the sailors were being questioned by Iranians. By 2:45 p.m., the military lost all communication with the boats.

Navy command launched search-and-rescue operations soon after, deploying aircraft from USS Harry S. Truman and nearby Navy vessels. The Navy tried to contact Iranian military units operating near the Gulf’s Farsi Island over marine radio and telephoned Iranian coast guard units. At 6:15 p.m., U.S. Navy cruiser USS Anzio got word from the Iranians that the sailors were in Iranian custody and were “safe and healthy.”

CENTCOM said armed Iranian personnel boarded the U.S. boats and led the sailors at gunpoint to a port facility on Farsi Island. The Americans were held for about 15 hours and were not physically harmed. They were released at 8:43 a.m. GMT the next day to the Navy, and another group of U.S. sailors took over their vessels.

All weapons, ammunition, and communication gear on the boats were untouched, but two SIM cards appeared to have been removed from two handheld satellite phones, CENTCOM said.

The Navy has launched an investigation into the incident, which was seen as a test case for newly improved U.S.-Iranian relations. U.S. and Iranian officials were quick to hail the diplomacy that resulted in the release of the sailors. President Obama said Sunday that increased cooperation between the two nations prevented the capture from escalating into “a major international incident.”

“Some folks here in Washington rushed to declare that it was the start of another hostage crisis,” Obama said. “Instead we worked directly with the Iranian government and secured the release of our sailors in less than 24 hours.”

The incident preceded a couple of breakthroughs in U.S.-Iran relations. Days later, international inspectors formally certified that Tehran had dismantled most of its nuclear program in accordance with the historic deal brokered last year between Iran and six world powers. In exchange, the Obama administration lifted a swatch of economic sanctions that have crippled Iran’s economy for years. The two nations also agreed to a prisoner swap that would release four Americans, including a Washington Post reporter, held prisoner in Iran for months or years. A fifth American was also released, but not as part of the exchange.

What Tinder and Halo Have in Common

A familiar modern scenario: You spend hours in matchmaking waiting to get picked for a quick game of Halo, but see no results. You’re swiping right all day on Tinder, but nobody swipes back. In the 21st century, browsing for dates can seem a lot like being stuck while looking for matches in a multiplayer game lobby. Even when you’re itching to play, you can’t get started until the game shows you a match you might be interested in.

Comparisons between dating and gaming are commonplace in modern culture, and thanks to a recent profile on Tinder from Fast Company, it turns out this connection is less superficial than many might think. Just as more matches become available when a Call of Duty player “ranks up,” Tinder queues mysteriously start to fill with prospects when the app’s users deem you “more desirable.” So how does this happen?

More From Our Partners The Rise of Dating Sims for Women This Glados-Inspired Robot Brings Science to Dating Apps The Year in Weird

The Rise of Dating Sims for Women This Glados-Inspired Robot Brings Science to Dating Apps The Year in Weird According to its CEO, Jonathan Badeen, Tinder uses a variation of ELO scoring to determine how members rank among the site’s userbase, and therefore, which profiles to suggest and whose queues profiles show up in. Invented by the physics professor Arpad Elo to determine rankings among chess players, ELO assigns ranks by judging players’ presumed skill levels against each other. If two players with the same ELO rank play each other, their rank should stay the same regardless of the outcome of the match, to reflect their similar skill level. If a player with a high ELO rank plays a lower-ranked player, though, then the system uses the difference between their ELO scores to recalibrate their rankings.

If the high-ranking player beats the low-ranking player, then her ELO score will only go up a small amount, to reflect the suspected ease of the matchup and suggest more challenging opponents in the future. But if a higher-ranking player loses to a lower-ranking player, her ELO score will drop significantly, to reflect the severity of the upset. As a result, she may find herself matched against lower ranking players until she can prove she’s ready for a tougher opponent.

“I used to play a long time ago, and whenever you play somebody with a really high score, you end up gaining more points than if you played someone with a lower score,” explained Badeen, recalling his days playing Warcraft. “It’s a way of essentially matching people and ranking them more quickly and accurately based on who they are being matched up against.”

The result is a system where rankings are determined by how users compare to other people rather than their personal stats. The system has since been adapted for use in football, baseball, and even video games such as League of Legends and Warcraft. So when translated to Tinder, the algorithm can be understood on a basic level as one where who you match with determines who the app shows to you. Get matched with those with a high ELO, and the site will start populating your queue with the people Tinder as a whole finds more desirable. Get matched with those sporting a lower ELO, and the site will only show you people who don’t get as many matches from high-ranking users. Your ELO is determined by the supposed desirability of the people who think you’re worth dating.

Browsing for dates on Tinder can seem a bit like being stuck while looking for matches in a multiplayer game lobby.If you want Tinder to think more highly of you, you need to match up with a greater number of popular users and fewer unpopular users. The data analyst Chris Dumler calls it a “vast voting system,” and the site asserts that it’s different from attractiveness ranking app Hot-or-Not because profile pictures aren’t the only factor in who might match with you. Workplace, education, and other self-summary sections play just as important a role. Essentially, the key isn’t how many people find you attractive, but which people think you’re worth dating.

For a competitive system where everyone is trying to achieve the same goal—win—this makes sense. But attraction is a personal thing, and a system like this might leave many feeling under-served. What if higher-ELO people match with you, but you’re actually interested in the type of people who normally have lower-ELO ranks? Just because other high-cheekboned and full-lipped ELO titans aren’t interested in them doesn’t mean you wouldn’t be. You might even be driven away by traits that Tinder as a whole finds more attractive. But because the high-ELO community has deemed you worthy, your queue will be filled with them while the type of people you’re actually interested in remain out of reach.

And then there are the users who have trouble finding matches at all, the Tinder equivalent of ELO Hell. Coined by the League of Legends community as being stuck in lower-level matches or not even being able to find opponents, ELO Hell is when a player is stuck below what they consider to be their skill level (which is often blamed on incompetent teammates). Because these players’ options for matchups are so limited to begin with, they feel their rank is being kept lower than it should be simply because they don’t have the chance to prove themselves in the first place.

Dating is often framed as a competition, where one has to strive to attract as many people as possible. In this context, it might make sense to use a system born out of competition to rank which “leagues” people fall into. But the end goal of dating is one of the biggest cooperative endeavors people can take on together. Which raises the question: Is a system born out of a war game like chess really the most appropriate way to judge compatibility?

This post appears courtesy of Kill Screen.

January 17, 2016

Close, but No Rocket Landing

If at first you don’t succeed at landing a rocket on a ship floating in the middle of the ocean, try, try, try again.

That’s the plan for SpaceX, which on Sunday afternoon narrowly missed a full touchdown of its Falcon 9 on an ocean platform in the Pacific Ocean on its return trip from delivering a satellite to space earlier in the day.

“Definitely harder to land on a ship,” tweeted Elon Musk, the billionaire founder of the private spaceflight company. “Similar to an aircraft carrier vs land: much smaller target area, that’s also translating & rotating.”

Musk said that the Falcon 9 successfully slowed down enough to make a solid landing, but one of the rocket’s legs failed to lock, leading the spacecraft to tip over. It could have been worse, of course: SpaceX’s last two attempts at such ocean landings ended with the rockets exploding.

SpaceX made aerospace history last month, when it launched a Falcon 9 rocket into space and brought it back to Earth in one piece, landing it upright. But that touchdown happened on a launch pad, and not on what is effectively a giant, flat buoy.

The ocean platform—about 300 feet by 100 feet, with wings that add 70 more feet to its width—is equipped with thrusters to help it stay in place in the water, but is not anchored to anything. The Falcon 9 is 14 stories tall and must go from traveling at nearly 1,300 meters per second—or just under 1 mile per second—to just two meters per second before it lands. Stabilizing the rocket for reentry, SpaceX explains, “is like trying to balance a rubber broomstick on your hand in the middle of a wind storm.”

The Falcon rocket successfully carried a U.S.-European satellite from California to low-Earth orbit Sunday morning. Jason-3 will float around 830 miles above the planet, tracking the rate of global sea-level rise, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Here it is in its new home:

#Jason3 satellite in orbit to monitor sea level rise! Solar arrays deployed & power positive https://t.co/3avbEwM8gF pic.twitter.com/SUL22dTzqs

— NASA (@NASA) January 17, 2016

The Search for Missing Americans in Iraq

The U.S. State Department is investigating reports by Middle Eastern media that American citizens are missing in Iraq, officials said Sunday.

Al Arabiya, a Saudi-owned Arab news outlet, reported Sunday that three Americans have been kidnapped by “militias” in Baghdad, citing its own sources.

State Department spokesman John Kirby said that the agency is aware of the reports.

“The safety and security of American citizens overseas is our highest priority,” Kirby said in a statement. “We are working with the full cooperation of the Iraqi authorities to locate and recover the individuals.”

The State Department would not say how many Americans are reported missing. The U.S. Embassy in Baghdad told the Associated Press that “several” Americans were kidnapped.

The Americans, all contractors, went missing two days ago, reported CNN, citing a senior security official in Baghdad. Their disappearance was reported by the company where they worked, CNN wrote.

The kidnapping report comes amid a worsening security situation in Baghdad and the surrounding area, and nearly one week after armed attackers stormed a mall in the Iraqi capital and detonated suicide and car bombs, killing at least 18 people and injuring 50 more. Following the assault, which lasted about an hour and a half, authorities shut down the city’s Green Zone, a heavily guarded area that is home to several foreign embassies, including that of the United States, and Western private military contractors.

This is a developing story and we’ll update as we learn more.

Can Clinton Stop Her Slide?

Don’t tell anyone, but there’s a Democratic primary debate tonight.

The Democratic National Committee has understandably been mocked for suspiciously scheduling most of the party’s debates during times when few people are likely to be watching. The last two were on Saturday nights, and this one—in South Carolina and airing on NBC at 9 p.m.—comes in the middle of a holiday weekend.

It’s a shame, because the race between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders is actually getting interesting—or as Clinton has been saying, it’s the “get real period” of the primary. Sanders is closing the gap with Clinton both in national polling and in Iowa while maintaining his lead in New Hampshire. The increasingly plausible prospect that Clinton could lose the first two early-voting states has prompted her campaign to challenge Sanders more aggressively on the issues. She has picked a fight with him over one of his core issues, Wall Street reform, and she has stepped up attacks on his gun record. And in Clinton’s most unusual move, her campaign deployed Chelsea Clinton to criticize Sanders’s support of a single-payer health-care plan from the right, arguing that it would mean gutting Obamacare and kicking people off their insurance.

Sanders, in turn, has drawn a sharper contrast as well. While the Vermont senator has vowed not to run attack ads, he filmed a commercial implicitly criticizing Clinton over her ties to Wall Street. “There are two Democratic visions for regulating Wall Street,” he says in the ad. “One says it’s okay to take millions from big banks and then tell them what to do.” Even though Clinton’s name wasn’t mentioned, her campaign accused Sanders of running an “attack ad” and breaking his pledge against negative campaigning. Meanwhile, Martin O’Malley was probably just miffed that he was left out of the whole kerfuffle.

Speaking of the former Maryland governor, he will be in Sunday night’s debate, having just barely cleared NBC’s threshold for inclusion. That came as a bit of a surprise to NBC’s own Jimmy Fallon, who had Clinton on his show Thursday and was under the impression that only she and Sanders would be debating—until Clinton rather awkwardly reminded him that O’Malley would be there, too. It has been clear for a while now that O’Malley probably won’t win the Democratic nomination, but as my colleague Nora Kelly noted, the tightening of the race between Clinton and Sanders actually makes O’Malley more relevant in Iowa, where because of the complicated caucus format, his voters could help break a tie.

For Clinton, however, the start of 2016 has been a nightmarish flashback to this time eight years ago, when Barack Obama’s victory in Iowa gave him the momentum to upend her bid for the Democratic nomination. The most concerning numbers for Clinton are not those that show a closer head-to-head race with Sanders; they’re the ones that have Sanders, who is six years older than Clinton, drawing more support among younger voters and performing better in hypothetical match-ups with Republicans. For all the talk about how a self-described Democratic socialist could never win a general election, the polling snapshot makes Sanders look like he could be the party’s best bet in the fall. Clinton’s struggle has sent Democratic bigwigs into a fairly predictable tizzy as they worry that despite the general-election polling, he’d be a far weaker candidate than Clinton. “I’m deeply concerned that in November swing voters are not going to vote for a socialist,” Representative Steve Israel, the retiring former Democratic campaign chairman, told The Washington Post.

As she did eight years ago, Clinton has put up a strong front. Her campaign always expected a close race, she’s said, and she told Fallon on The Tonight Show that her much bigger lead for much of last year was “artificial.” But the campaign’s more aggressive posture toward Sanders speaks even louder. Clinton hasn’t hesitated to go after Sanders in the first three Democratic debates—will she punch even harder on Sunday night? And will she continue to go after him on the issues, or will she shift to an electability argument? Whatever the strategy, it’ll be the last opportunity for Clinton and Sanders to confront each other before both the Iowa and New Hampshire contests. The debate might be buried in the middle of a three-day weekend, but it should be one to watch.

Obama's Diplomacy Days

Updated on January 17 at 1:09 p.m. EST

President Obama on Sunday hailed the release of Americans from Iranian custody and the implementation of an historic accord to curb Iran’s nuclear program, pointing to the breakthroughs as products of diplomacy.

“The United States has never been afraid to pursue diplomacy. We could advance by engaging directly with the Iranian government,” Obama said in a statement from the White House. “We’ve seen the results.”

The organization tasked with inspecting and monitoring Iran’s nuclear stockpiles and sites formally certified Saturday that Tehran had fulfilled the commitments of the nuclear deal brokered last year and dismantled most of its nuclear program. Inspectors of the International Atomic Energy Agency said the country had taken concrete steps to scale back its nuclear infrastructure over the past three months—quite literally, as my colleague Matt Ford pointed out, as in the case of the nuclear reactor core at Arak, which was covered in concrete.

Administration officials say that if the Iranian government were to go back on the deal now, it would take more than a year for the country to create a nuclear bomb.

In exchange, President Obama signed an executive order that revoked or amended five earlier executive actions, lifting economic sanctions against Iran that have crippled the nation’s economy for years. The European Union and the United Nations also removed sanctions against the country.

“We’ve achieved this through diplomacy without resorting to another war in the Middle East,” Obama said.

The administration imposed new sanctions, however, against some Iranian citizens and companies in response to Tehran’s recent testing of ballistic missiles, which U.S. officials say violate United Nations resolutions.

Obama said negotiations on the nuclear deal sped up talks on other matters, like Iran’s imprisonment of several Americans. Four Americans were released Saturday and will make their way to the U.S. Sunday as part of a prisoner swap between the two nations. They were Jason Rezaian, a Washington Post reporter who was captured in July 2014 and convicted of espionage last year; Amir Hekmati, a former U.S. Marine captured in 2011 and sentenced to death for espionage in 201; Saeed Abedini, a Christian pastor held by Iran since 2012; and Nosratollah Khosravi-Roodsari, whom the administration only identified as a hostage this weekend. A fifth American, Matthew Trevithick, a researcher imprisoned for 40 days, was released separately of the swap; his name was also not previously reported.

As part of the swap, Obama granted clemency to seven Iranians indicted or imprisoned violating U.S. sanctions against Iran, which he described Sunday as “a one-time gesture to Iran, given the unique opportunity offered by this moment and the larger circumstances at play.” The U.S. also dropped cases against 14 other Iranians it sought to extradite from other countries.

Obama said Iran has agreed “to deepen our coordination” in the search for Robert Levinson, a former FBI agent who disappeared in Iran in 2007, and who, according to his family members, was part of the discussion that led to the prisoner swap. The president also announced that the two nations had reached a settlement on a financial dispute dating back to the 1980s that would save the U.S. “billions of dollars.” As part of this resolution, the U.S. will send back $400 million to Iran, plus $1.3 billion in interest, according to ABC News.

Obama said that, despite the prisoner swap and the implementation of the nuclear deal, “there are profound differences” between the two countries. Various U.S. sanctions against Tehran remain in place, and Iran remains on the State Department’s list of state sponsors of terrorism.

Obama’s remarks on Sunday close out a big week for U.S.-Iran relations, which have come a long way since the U.S. joined talks on Iran’s program for the first time in 2008 under the Bush administration. On Tuesday, the Iranian military detained 10 U.S. sailors on two small Navy vessels that had crossed into Iranian waters in the Persian Gulf, prompting critics of closer U.S.-Iran ties to accuse Iran of aggression. But the situation was resolved within 24 hours by diplomats on both sides, and the sailors were allowed to go on their way.

Son of Saul and the Intimate Mechanisms of Genocide

“I will.”

“I will.” This is the first line spoken by Saul Ausländer (Géza Röhrig), 11-and-a-half minutes into Son of Saul, the Hungarian Holocaust drama of which he’s the protagonist. And these two brief words, when they finally come, are freighted with contradictory meanings.

Saul is a member of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz, the Jewish prisoners who were tasked with escorting their fellow Jews into the death chambers and disposing of their corpses afterward. Though the status was presented by the Nazis as a privilege—the Sonderkommando could remain alive somewhat longer than their condemned brethren—it was in fact a deeper curse: they, too, would be exterminated in a matter of time, but only after being forced to collude in their own genocide.

In this sense, Saul’s “I will,” is merely the acquiescence of the enslaved, the acceptance of yet another in an endless series of grotesque duties. Yet given their context, the words are also a gesture of quiet defiance. Saul has seen the dead body of a boy he believes to have been his son: In volunteering to take responsibility for the corpse, he is setting in motion a plan—one which will serve as the central thread of the film—to spare the boy from the ovens and give him a proper Jewish burial.

Son of Saul is the debut film of 38-year-old director László Nemes, and it is a work of remarkable power, a chilling investigation into the intimate mechanics of mass murder. We watch as the Sonderkommando herd unknowing victims into the “showers,” while German officers promise a hot meal on the other side. When the doors close, we watch them immediately begin to collect the belongings of the doomed, even as the latter begin to scream inside. Afterward, we watch them drag out the naked bodies and scrub down the floors for victims yet to come. We watch them shovel coal for the ovens; we watch them shovel human ashes into a river.

Most of all, we watch Saul. The camera hugs him close throughout almost the entire film, peering over his shoulder such that it presents the camp from his perspective while keeping his face (and the large red X on his back that marks him as Sonderkommando) in the frame. Nemes uses shallow focus both to keep the audiences’ eyes on his protagonist and to keep the horrors surrounding him—the arbitrary executions, the ever-present corpses—at a slight remove that’s simultaneously humane and disconcerting. The narrow, box-like frame of the film emphasizes a profound sense of claustrophobia and containment.

The movie is at once clinical in its accumulation of small details and dreamlike in its execution, a waking nightmare through which Saul somnambulates, the audience right alongside him. Röhrig, a poet as well as an actor, is fascinating in his opacity. Though the discovery of the boy has given him a goal, it’s clear that any larger sense of purpose he might have harbored has long since been extinguished. Survival itself seems hardly worth the effort.

The movie is at once clinical and dreamlike, a waking nightmare through which Saul somnambulatesNuggets of genuine horror abound. The German guards refer to Jewish corpses as “pieces” (“Move the pieces!” “Burn the pieces!” “One Jew for one piece!”). The initial reason why the boy whom Saul believes to be his was singled out is that he didn’t quite perish in the gas chamber. In a cruel inversion, a white-jacketed Nazi doctor places a stethoscope on the boy’s chest to listen to his vitals, before covering his mouth and nose to end his breathing. An autopsy is commanded not in order to determine the cause of death but rather to determine the cause of non-death.

Even as Saul pursues his solitary mission, an uprising is being plotted around him. (There was, in fact, a Sonderkommando revolt that took place at Auschwitz in 1944.) It’s here that Nemes perhaps offers more detail than is necessary. The elements of the insurrection and the power dynamics between the various Sondercommandos—the kapos and oberkapos, the competing units—all remain decidedly hazy. Though perhaps that’s precisely the point.

Son of Saul has already won the Grand Prix at Cannes and the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film, and it’s a clear favorite at the Oscars next month. It is not—if my description has somehow failed to make this clear—an easy film to watch. But it is a forceful and unsettling addition to the cinema of the Holocaust, a film that digs deeply into the gruesome workings of the death camps and ponders questions about duties to the living and duties to the dead.

My Grandmother, My Mother, My Sister, and Me

Renowned street photographer Arlene Gottfried has created her most intimate work to date for her new book, titled

Mommie

. A collection of portraits of her mother, grandmother, and sister over the course of the last 40 years, it features them eating, getting dressed, and getting old. They share everything, from clothes to cheekbones. The effect is of more than a series of pictures of a family; it becomes a portrait of time. “I wanted to try and capture them more,” Gottfried said to The Atlantic. “To stop time and hold onto them.”

Renowned street photographer Arlene Gottfried has created her most intimate work to date for her new book, titled

Mommie

. A collection of portraits of her mother, grandmother, and sister over the course of the last 40 years, it features them eating, getting dressed, and getting old. They share everything, from clothes to cheekbones. The effect is of more than a series of pictures of a family; it becomes a portrait of time. “I wanted to try and capture them more,” Gottfried said to The Atlantic. “To stop time and hold onto them.”

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower