Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 164

May 17, 2016

The Senate's Unanimous Vote to Let 9/11 Victims' Families Sue Saudi Arabia

A bill that would allow the families of 9/11 victims to sue Saudi Arabia for any role in the attacks is one small step closer to law Tuesday, after the Senate passed it unanimously. The bill goes on to the House, but the White House has promised to veto it.

So far, there’s been no public information linking the Saudi government to the attacks. But there are 28 pages of documentation from a congressional inquiry, which are said to detail links between Saudi officials and the hijackers. The Obama administration, pressured by former Senator Bob Graham and the families of victims, has promised to release those pages soon, though it hasn’t given a date yet. (Other officials suggest the pages may not really offer much of a smoking gun at all.)

In a statement, the families of several 9/11 victims applauded the Senate’s passage of the measure:

The American people, as well as our families, deserve the truth about 9/11 and those responsible deserve to be held to account. JASTA promises us the truth, accountability and a strong warning that the United States finally will stand behind its promise of justice to those who were injured and the survivors of the three thousand children, mothers, fathers, wives and husbands who were murdered in our homeland on 9/11.

But the White House has remained staunchly against the bill. While Obama has broken with the Saudis on key issues recently, administration officials warn that the proposed law could expose U.S. officials and members of the armed forces to prosecution overseas. That means that even if the House follows suit, the bill’s path to law remains a tough one.

An Indictment For 20,000 Gallons of Oil Spilled in the Pacific

The company operating the oil pipeline that burst in May 2015 near Santa Barbara, California, and spilled more than 100,000 gallons of crude near a protected state beach park has been indicted, the company announced Tuesday.

Plains All American Pipeline, based in Houston, Texas, said it and one of its employees have been indicted on 46 counts related to the spill. In a statement, the company defended itself, saying:

Plains believes that neither the company nor any of its employees engaged in any criminal behavior at any time in connection with this accident, and that criminal charges are unwarranted. We will vigorously defend ourselves against these charges and are confident we will demonstrate that the charges have no merit and represent an inappropriate attempt to criminalize an unfortunate accident.

The company’s pipeline broke May 19 near Refugio State Beach, which is just west of Santa Barbara and surrounded by the Los Padres National Forest. The pipeline had deteriorated to such a point that it’d worn down to 1/16 of an inch in some places, and also had a six-inch crack, federal investigators with the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. Of the 101,000 gallons spilled, more than 20,000 found its way into the Pacific Ocean and killed more than 120 birds, and 65 marine mammals.

The the Los Angeles Times reported that in the 12 years before the Santa Barbara spill, Plains All American Pipeline had been connected to dozens of spills releasing almost 2 million gallons “of hazardous liquid” in Canada and the U.S.

In its defense, Plains All American Pipeline said it’d spent $150 million in cleanup-costs and spill-related matters.

Why American Sanctions on Burma Are Easing

Following Burma’s historic elections last November and the transition of power away from the military to a new ruling party in April, the United States is ready to start lifting sanctions against the Southeast Asian country.

Recognizing Burma’s strides toward a democratic government, the Obama administration announced Tuesday it was lifting sanctions on 10 state-run companies and banks in the country that is also known as Myanmar. In April, the party of former political prisoner Aung San Suu Kyi took power. But the military, which ruled for five decades, still has political and economic influence.

Announcing the lifting of sanctions, President Obama said in a statement:

The Government of Burma has made significant progress across a number of important areas since 2011, including the release of over 1,300 political prisoners, a peaceful and competitive election, the signing of a Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement with eight ethnic armed groups, the discharge of hundreds of child soldiers from the military, steps to improve labor standards, and expanding political space for civil society to have a greater voice in shaping issues critical to Burma's future.

The president, however, did say that despite the progress, Burma poses an “extraordinary threat” to U.S. interests and will keep trade and investment restrictions on the military.

U.S. businesses have complained there hasn’t been enough room to invest in Burma because of sanctions. As the Associated Press reports:

Although several major U.S. firms like Coca-Cola, General Electric, Chevron and Caterpillar are now operating in Myanmar, U.S. investment of $248 million represents less than 1 percent of total foreign investment there, a much lower proportion than in other Southeast Asian countries.

Further, the AP reports there are still concerns among U.S. lawmakers and humanitarians that ethnic minorities will continue to be targeted in the country.

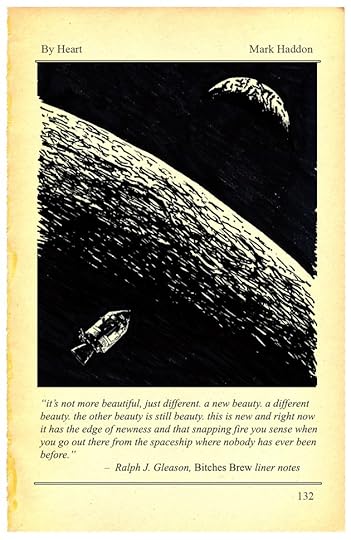

Art Should Be Uncomfortable

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Karl Ove Knausgaard, Jonathan Franzen, Amy Tan, Khaled Hosseini, and more.

Doug McLean

Mark Haddon, the author of The Pier Falls, likes art that makes people uncomfortable. He’s felt that way ever since he first fell in love with Miles Davis’s 1970 masterwork Bitches Brew—a divisive, brilliant record that continues to both thrill and alienate listeners. In a conversation for this series, he explained how the album and its Ralph J. Gleason-penned liner notes helped him develop a taste for singular and unsettling work that feels like stepping out onto an unfamiliar planet. He discussed his attraction to works that stake out radically new terrain, even though that usually means losing some people along the way.

Haddon’s own writing seems to grow out of discomfort, too. He described his process as a kind of willful isolation, a grueling self-imprisonment he’s learned will yield results. Maybe it’s no accident that the characters in The Pier Falls, Haddon’s first story collection, tend to find themselves trapped in confining physical spaces: an ominous island, a depressing apartment, the bottom of a cave. In “The Woodpecker and the Wolf,” the astronaut protagonist battles hunger and malaise inside a tiny capsule, the last surviving member of a failed Martian colony. “That was why they’d been chosen, wasn’t it,” she reminds herself, “their ability to accept, to be patient, to endure.”

Mark Haddon is the author of the best-selling novels A Spot of Bother, The Red House, and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, which won a Los Angeles Times Book Prize and was recently adapted into a Tony Award-winning play. He lives in Oxford, England, and spoke to me by phone.

Mark Haddon: Growing up, I should have been listening to the Sex Pistols and The Clash like everyone else under 18 in the U.K. But I was sent away to a boarding school as a teenager, so I was pretty cut off from the mainstream youth culture. It was a pretty unpleasant place, and I never felt at home, which is one of the reasons why I’ve never been a joiner, a belonger. In that strange, hermetically sealed little world in the middle of the English countryside, I think I was seeking out a music of my own—something I could like that no one else liked. Outsider’s music.

Having heard very little music beyond my father’s mild jazz collection and “Top of the Pops” every Thursday night, I hadn’t had too many formative listening experiences, but on two occasions, I heard a piece of music that changed the way I saw the world. The first was Benjamin Britten’s “Hymn to St. Cecilia,” which was performed at school by the choir. And the second was hearing Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew.

Now, I know Miles Davis is hugely popular, but he wasn’t popular in the English shires of the late 1980s. I think I understood at the time that I was listening to something absolutely extraordinary: the sound of someone inventing a completely new language, one that was nevertheless totally whole and articulate.

It wasn’t just the music that struck me; it was also Ralph J. Gleason’s liner notes. The music and the liner notes together were a guide to an entirely new world. There’s a passage at the end that moved me then and still moves me now:

it’s not more beautiful, just different. a new beauty. a different beauty. the other beauty is still beauty. this is new and right now it has the edge of newness and that snapping fire you sense when you go out there from the spaceship where nobody has ever been before.

This is the definition of art that has always most excited me: the feeling of being taken to the boundary of the universe, then beyond that boundary into the surrounding darkness, and you’re the first person to ever be there. It’s not an experience that happens very often, but I’m willing to wait. I’ve never been someone who’s enjoyed music in general, or contemporary fiction in general, or films in general, or theater in general. I feel I’m standing on the runway waiting for the next big one to come in, carrying some of that outer darkness with it.

Just reading the liner notes lines again, I realize there was something else that was clearly important for me about this passage. I was born in ’62 and, like a lot of kids of that generation, the space program was hugely important in our imaginations. I wanted to be an astronaut—we all did. Of course, it rapidly dawned on me that I was too anxious and oversensitive to be an astronaut. Besides, you had to become a military pilot, and I had a lazy eye and wasn’t that keen on learning how to kill people. But reading this passage is a reminder that there are other ways to get to far-flung places at the edge of the universe.

I feel I’m standing on the runway waiting for the next big one to come in, carrying some of that outer darkness with it.

I also love the fact that the liner notes are all written in lower case. I’d forgotten this until recently. Whenever possible, I still write in lower case. I always curse at modern word-processing programs, which assume you want a capital letter at the beginning at every sentence, a capital letter for everyone’s name, a capital letter every time you say “I”. Occasionally, when I have the time, I’ll actually go back and meticulously take them out because they look so untidy to me. It all goes back to that music and those liner notes. It still feels like a radical way to write sentences.

There’s only one passage in the liner notes that fails to ring wholly true for me. Gleason writes, “we can always listen to ben play funny valentine, until the end of the world it will be beautiful and how can anything be more beautiful than hodges playing passion flower?” He’s saying that new forms don’t invalidate the old forms, which retain their power. And maybe that’s true for some listeners, but less so for me. As I grew older, I stopped listening to most jazz that was recorded before Bitches Brew, and quite a lot recorded after it. It took me a while to formulate exactly why. It think it’s this: If I can imagine something being played in a hotel foyer, it’s not the kind of music I want to listen to.

Sadly, a lot of jazz—which was intimately interwoven with the experience of slavery and subsequent continuing oppression of black Americans, a music of protest, a celebration of pride and difference—was co-opted by commerce. As most things are, eventually. It’s become background music for most of us, and for me it kind of lost that angry beauty. I’ve come to realize that much of the music I like is music that is going to annoy people sitting in that metaphorical hotel foyer. Not lyrically but musically. Bitches Brew passes that test—it’s beautiful, but it’s not bland.

When a writing student shows you a piece of writing that’s not working, it’s relatively easy to help them improve. But it’s very hard—if not impossible—to tell someone positively how to write brilliantly. After all, there would be more brilliant writing if you could. I think it’s because the best writing—like the best music, the best theater, the best art—always does something you don’t expect, in a way that you don’t expect. It doesn’t have to be radical, it doesn’t have to be a wholly new invention, but is has to surprise you in some way. If it’s merely an improvement on what went before—that’s just craft, isn’t it?

I’ve come to realize that much of the music I like is music that is going to annoy people sitting in that metaphorical hotel foyer.

I think it was Jean Cocteau who said fashion is what seems right now and wrong later. Art is what seems wrong now and right later. Great art has that slight discomfort to start with: It takes you a while to think, yeah, this is right. I just didn’t realize that it was right at the time. I think art grows out of a place of discomfort, too—for me it does, at any rate. I’ve come to accept that I’m going to be bored and frustrated for long periods. I’ve come to accept that I’ll be regularly dissatisfied and that I’ll have to throw a lot of stuff away. I have to be patient and slog onward and trust that something better will come along. It’s not a kind of moral strength, I don’t think. It’s a necessary balance between grandiose self-confidence and withering self-criticism. I spend a lot of time pacing up and down getting absolutely nothing done, but it seems to pay off in the end.

I often say to people when I’m teaching, if you’re having fun it’s probably not working. And for me, the job of writing is pretty uphill most of the time. It’s like climbing a mountain—you get some fantastic views when you pause or when you get to the top, but the actual process can be tough. I’m sure there are people out there who enjoy writing, and I wish them all the best, but I’m not like that. I wish I could enjoy the process more, but I think I’ve come to accept that for it to work, I have to be uncomfortable.

The liner notes and music from Bitches Brew are connected in my mind as they are connected for no one else on the earth: with a little illustration which I first saw in a science book I had when I was a little kid. It was a reproduction of an engraving from Camille Flammarion’s 1888 book L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire, which depicts a fake medieval landscape, and a guy in a gown who has walked to the edge of the picture, to the edge of the earth. He’s somehow managed to poke his hand under the bottom of the lowest, nearest of the bounding spheres, and behind it he sees the machinery of the universe: the cogs and the wheels and the smoke and the fire. That’s what I want art to feel like, and for me it’s always connected with Gleason’s image of stepping outside the spaceship.

The Ancient Military Barracks Hidden Under Rome’s Streets

Workers in Rome will have to change the design of a new subway station after discovering military barracks that date back to the second century during the rule of Emperor Hadrian.

The ruins at the Amba Aradam station span 9,700 square feet and lie 30 feet below street level. They once housed the Praetorian Guard, the emperor’s bodyguards, according to archaeologists. The area includes a hallway and 39 rooms, where archeologists have found bronze bracelets, mosaics, and human remains.

Rossella Rea of Italy’s Culture Ministry, in announcing the discovery on Monday, told the Associated Press:

It’s exceptional, not only for its good state of conservation but because it is part of a neighborhood which already included four barracks. And therefore, we can characterize this area as a military neighborhood.

Officials told the BBC that work on the city’s third subway line would not be delayed and is on schedule to open in 2020. Workers will construct around the ruins. The station will be located near an interchange at the Colosseum.

Elon Musk Is Sorry Foreign Workers May Have Built His Factory For $5 an Hour

The owner of Tesla Motors has vowed to investigate news reports that found foreign workers hired by a subcontractor to build a Tesla factory in California were paid just $5 an hour.

Elon Musk on Monday acknowledged a recently published investigation by The San Jose Mercury News that found a company hired to build a paint shop for Tesla in Fremont, California, underpaid more than 140 workers it brought to the United States on visas for temporary business visitors. The report centers on a Slovenian man, Gregor Lesnik, who was paid less than minimum wage by ISM Vuzem, a construction company based in Slovenia.

Musk said Monday he did not know about the situation and would investigate. Here’s part of his statement:

There are times when mistakes are made, but those are the standards to which we hold ourselves. With respect to the person at the center of this weekend’s article in the Mercury News, those standards were not met. We are taking action to address this individual’s situation and to put in place additional oversight to ensure that our workplace rules are followed even by sub-subcontractors to prevent such a thing from happening again.

… Assuming the article is correct, we need to do right by Mr. Lesnik and his colleagues from Vuzem. This is not a legal issue, it is a moral issue. As far as the law goes, Tesla did everything correctly.

The San Jose Mercury News reported Lesnik was injured on the job after he fell three stories from a roof, and that ISM Vuzem tried to get Lesnik out of the country to cover up issues with its visas and working conditions.

ISM Vuzem was contracted by Eisenmann, a German-based industrial systems manufacturer, which Tesla hired to build its new paint shop. The workers from Slovenia and Croatia had been promised nearly $13 an hour (still a fraction of the $52 an hour paid to Americans for similar work), and when they arrived they logged up to 70 hours a week with no overtime pay, and hourly earnings beneath the minimum wage. Lesnik has sued all companies involved, claiming he and the other workers are owed $2.6 million for their promised pay and overtime.

'Preventable Tragedy': Amtrak 188 and the Case for Positive Train Control

In the aftermath of Amtrak 188’s deadly derailment one year ago, investigators, journalists, passengers, and the public all sought some explanation for how Brandon Bostian, an experienced, skilled, and meticulous engineer, crashed his train in Philadelphia. Had there been a mechanical failure? Was Bostian too tired, or impaired for some reason, to concentrate? Had he been speaking on a cellphone? Was the locomotive hit by rocks?

But the National Transportation Safety Board, in findings revealed Tuesday morning, has concluded the cause of the crash was far simpler: Investigators believe Bostian was distracted by radio traffic about rocks striking another train at the worst possible moment, leading him to run the train far too fast through a curve and derail. NTSB Chairman Christopher Hart used that conclusion to make an impassioned call for full implementation of Positive Train Control, a technological fail-safe that’s intended to prevent collisions and derailments.

Related Story

“An engineer who is not fatigued, distracted, or impaired is not infallible on their best day,” Hart said. “Our investigation is to see whether the engineer was backstopped by safety technology such as PTC, or positive train control. At the time of the accident, PTC was not implemented on the portion of track where the derailment occurred. If a PTC system has been active, this treatment not have derailed. Close to 200 passengers would not have been injured and 8 other passengers would still be alive today.”

The NTSB released a huge tranche of documents in the public docket for the case in February, but offered little in the way of conclusions about the cause of the accident.

The theory that Bostian might have been affected by rocks hitting the train emerged early on. There’s a logic to it: Trains are often struck by rocks, especially in the urbanized corridors of the Northeast. Besides, another train—a regional Philadelphia SEPTA train—had been “rocked” the same evening, and Amtrak 188 passed that train where it had pulled off, in part because the engineer had been injured by glass after being struck. NTSB concluded that though the windshield of Amtrak 188’s locomotive was cracked, the train had not been rocked.

Instead, Bostian was distracted by the radio traffic concerning the SEPTA train, which apparently prevented him from throttling down at a crucial moment. The area where Amtrak 188 derailed features several stretches where a train speeds up and slows down, but instead of slowing down when it should have, the train sped up to 106 miles per hour just before derailing. Investigators speculated that though Bostian knew the route well, his distraction might have led him to believe he had already passed the curve, so that he sped up too soon.

Bostian remains an enigma—the tragic figure at the center of the disaster. He cooperated with investigators, and reported having no memory of the time leading up to the crash, though the NTSB reported that the engineer had been moving the throttle during that stretch. He was concussed in the accident. Obsessed with trains since his childhood, Bostian had worked to achieve his dream job as engineer. Colleagues interviewed after the crash recalled him as an excellent engineer, toxicology tests came back negative, and his phone was turned off at the time of the derailment. The train was on time, and there was no indication that Bostian was trying to make up for lateness, a factor in some legendary train wrecks.

While the NTSB ruled out mechanical failure as a cause for the crash, it also found that windows on the train popped out, and that if the windows had remained in place, some passengers would not have been ejected, and might not have been as badly injured.

The fact that an engineer like Bostian could be at the controls for a horrific accident is chilling, but as Hart noted, it’s not the only case. There were deadly rail crashes in California in September 2008 and the Bronx in December 2013, both of which would likely have been avoided by PTC. In total, NTSB has calculated that PTC would have prevented 145 accidents since 1969, in which 288 people were killed and nearly 6,600 were injured.

Amtrak has since implemented PTC on the stretch in Philadelphia where the crash occurred, as well as throughout most of the Northeast Corridor. Generally, however, the United States has been slow to adopt the technology. In 2008, Congress mandated that every railroad with intercity passenger service, commuter service, or hazardous materials install PTC by the end of 2015. But railroads have pushed back on the mandate. Amtrak, which is perpetually strapped for cash, said it could not afford to meet the deadline. Commercial railroads have lobbied aggressively against the deadline as well, and late last year Congress agreed to extend the timetable by at least three years, to the end of 2018.

“As we discussed our findings regarding this preventable tragedy, let us keep in mind the deadline that matters is not 2018. It is not some later date made possible by a conditional extension,” Hart warned on Tuesday. “The deadline that really matters is the date of the next PTC-preventable tragedy.”

As the board voted on conclusions, in fact, Vice Chair Bella Dinh-Zarr, citing the importance of PTC, suggested relegating engineer error from the probable cause of the accident to contributing cause, while naming the lack of PTC as the probable cause. NTSB staff, however, opposed the switch, as did Hart, noting that the engineer is still responsible for following rules and that PTC is a safety net; Dinh-Zarr’s attempt was defeated.

That minor disagreement aside, the takeaway from the NTSB hearing was the importance of the new technology. But as Dinh-Zarr pointed out, NTSB has been advocating for PTC since 1970. So far, neither railroads nor regulators are listening closely.

May 16, 2016

What Killed Burlington College?

The end of the school year doesn’t just mark graduation at Burlington College, the small Vermont institution led by Jane Sanders from 2004 to 2011. The school announced on Monday that it will shut down later this month, facing insurmountable financial difficulties. The closure comes after years of difficulty for Burlington College, a small school founded in 1972 for nontraditional students.

“It is with great sense of loss to the educational community that Burlington College's progressive and unique educational model will no longer be available to students,” the school said in a statement.

Many of the school’s financial difficulties date to Sanders’s tenure as president. She has been a frequent presence alongside her husband, Senator Bernie Sanders, on the presidential campaign trail. In announcing the closure, the school blamed the "crushing weight of the debt" from the purchase of a new campus in 2010, during Sanders’s tenure. Burlington said its bank had pulled the school’s line of credit. The college was already at risk of losing its accreditation—which is essential for receiving federal funds and conferring legitimacy—if it could not resolve its financial difficulties.

When Jane Sanders became Burlington College’s president in 2004, she had previously served as interim president at Goddard College, her alma mater, about an hour east of Burlington. Bernie Sanders served as Burlington’s mayor from 1981 to 1989. (Jane Sanders holds a a doctorate in Leadership and Policy Studies from the Union Institute, a nontraditional school that critics sometimes call a diploma mill. Union made national headlines during the 2012 campaign because Marcus Bachmann, husband of then-Representative Michele Bachmann, also received his doctorate there.)

In an in-depth report on the school’s struggles earlier this year, Politico’s Maggie Severns laid out her approach:

In an interview with the Burlington Free Press at the time, she cited building enrollment and expanding the school’s small endowment as priorities. The college adopted a plan to offer more majors and graduate-degree programs, renovate its campus and grow enrollment a couple of years later. And in 2010, Sanders and the board went further: She brokered a deal to buy a new plot of lakefront land with multiple buildings from the Roman Catholic Diocese to replace the college’s cramped quarters in a building that used to house a grocery store. The college used $10 million in bonds and loans to pay for the campus, according to reports by the Burlington Free Press.

The land was 33 acres on the shores of Lake Champlain. Ironically, the diocese was selling the land at the time because it was cash-strapped. The purchase was huge—especially for a school whose annual budget didn’t crack $4 million. Jane Sanders plan was to bet big. To finance the deal, Burlington issued tax-free bonds, took a $3.5 million loan from the diocese, and received a $500,000 bridge loan from Tony Pomerleau, a wealthy local real-estate developer and close friend of the Sanderses.

But the land deal proved to be a white elephant. The school did increase its enrollment, slightly (on Monday, administrators said they had 70 students after last week’s graduation, plus another 30 who had placed deposits to join the incoming class), but not enough to make up the difference. Nor did donations rise enough to remain solvent.

Sanders left her post in 2011, for reasons undisclosed. Her successor Christine Plunkett tried to bring more financial stability but failed, and in 2014, its accreditor placed it on probation. Plunkett resigned. In November 2014, interim President Mike Smith sold 25 of the original 33 acres to a local developer for $7.5 million. Of that, $4 million went to the diocese to pay for the land—Burlington College hadn’t paid for all of it yet—and the rest went to the school’s bank.

That wasn’t enough, leading to today’s announcement. Burlington College was always a fragile concern. Its website notes that in the early days, it “had no financial backing, paid its bills when they came due, and paid its President when it could.” Jane Sanders’s plan to place a big bet on expansion in order to put the school on a more solid long-term footing was similar to decisions made by other college presidents, and sometimes those bets simply don’t work out.

But several questions at a press conference held by the school’s president and dean elicited surprising replies. Asked whether Jane Sanders was to blame for the closure, President Carol Moore and Dean Coralee Holm declined to answer, even as they acknowledged that that the college’s press release, in naming the land purchase as the reason for the closure, implicitly pointed a finger in her direction. Smith and Holm also declined to comment on whether there was a federal investigation into the college, or whether the FBI or other authorities had interviewed faculty, staff, or administrators, or if they’d sent any subpoenas. Those “no comments” may raise eyebrows, since it’s generally assumed that if the answer was no, administrators would simply have said so.

A spokesman for Bernie Sanders’s campaign said the campaign would not be commenting on Burlington College’s closure. Jane Sanders could not immediately be reached for comment.

There is no small irony to the fact that even as Bernie Sanders has made the crushing weight of student debt on many U.S. students a centerpiece of his campaign, the college his wife led has succumbed to its own crushing debt. Bernie Sanders has called for free tuition at public colleges and universities, which he says he would provide by increasing federal funding to cover two-thirds of the cost—in large by through a tax on the financial sector—while asking states to provide the final third. (Many observers have labeled that reliance on states unrealistic.) Sanders would seek to prohibit the federal government from profiting on student loans.

Burlington College, of course, is a private college, rather than a state-supported one. Politico noted that the average annual cost of more than $25,000 is more than $10,000 higher than the average for private colleges in the United States. Even as tuition has risen across the U.S., many smaller schools have struggled to keep up financially, and some have been forced to shutter. Burlington is now the latest member of that roll.

Network TV’s Future Is All About the Past

Every year, advertising and programming executives come together for an old-school gathering known as the network-TV upfront. And every year, amid discussions of the upcoming season of shows, there’s always talk of innovation. 2016 was no different. NBC has said it’s planning to cut back on Saturday Night Live’s ad breaks in favor of more “native” advertising, or branded content that appears within episodes. Meanwhile, ad firms continue to use data to figure out just how many people use their DVRs to fast-forward through commercials. Both sides are navigating ever-narrowing avenues of relevance, but you wouldn’t know that from the shows making it to the screen.

As the TV world grows more diffuse, the “Big Four” networks—which once took more risks on shows with iffy ratings potential in hopes of Emmy attention—have retreated to what they know will work. Crime procedurals, spinoffs, adaptations of famous films, and reboots of popular old shows matter most. Streaming networks like Netflix and Amazon are throwing money at original programming that can defy the strictures demanded by commercial breaks and timeslot competitors. Meanwhile, CBS, Fox, NBC, and ABC are going back to their glory days: a monoculture where the Law & Order creator Dick Wolf was the most important person in the business, and a TV version of the Lethal Weapon films might have actually appealed to young people.

That’s not to say the golden age of network TV was filled with creative triumph; the schedules presented at upfronts have always included cheaper cash-ins. But the already announced lineups from NBC and Fox are heavy with supposed “safe bets” that harken back to the days before cable and streaming networks started crowding the market. Meanwhile, more daring work like The Carmichael Show, a marginal hit on NBC, struggled to even get renewed, while CBS (perhaps the fustiest of the “Big Four”) apparently passed on a modern update of Nancy Drew because it skewed “too female.” That’s how risk-averse these networks have become: They’re afraid of shows that might appeal to half of the viewing audience.

CBS’s full lineup hasn’t yet been announced, but for years the network has thrived by embracing classic staples like procedural crime dramas (the CSI, NCIS, and Criminal Minds franchises) and broad laugh-track sitcoms (like Two and a Half Men, Two Broke Girls, and The Big Bang Theory). The approach has kept CBS at the top for more than a decade—though its programming doesn’t skew young (the 18-49 age bracket is the most crucial to advertisers), it’s broadly popular enough for that not to matter. Which explains the network’s reluctance to take chances: The female-led Supergirl, which debuted to big ratings that later declined, is being shuffled over to The CW, which already airs several superhero shows. That move, coupled with the fear that a Nancy Drew reboot was too niche for the network, casts a harsh light on CBS’s fierce commitment to the middle of the road.

Yet it isn’t an approach other networks are looking to copy. NBC’s lineup includes one exciting prospect, The Good Place (from the Parks & Recreation creator Michael Schur), a comedy set in the afterlife starring Kristen Bell and Ted Danson. But other than that, the network looks nothing like its more creatively adventurous days, when its schedule included low-rated but critically acclaimed shows like Community, Friday Night Lights, and 30 Rock. The bulk of new shows are related to existing hits, so the silly spy thriller The Blacklist gets a spinoff called The Blacklist: Redemption, while Dick Wolf’s empire of Chicago procedurals (Chicago Fire, Chicago P.D., Chicago Med) gets a fourth entry called Chicago Justice. NBC has also taken to sprucing up hoary old pieces of intellectual property: There’s the Wizard of Oz-inspired epic drama Emerald City, a Game of Thrones knock-off that transforms the world of Oz into a darker copy of Westeros, filled with magic and political intrigue.

As the TV world grows more diffuse, the “Big Four” networks have retreated to what they know works.

Fox’s lineup is even more reboot-happy. Along with existing adaptations like Gotham and Lucifer, the network is trying out new versions of Lethal Weapon and The Exorcist. Reworking film franchises that haven’t been popular since the mid-’90s may not make a lot of sense, but in the world of Peak TV, any kind of brand recognition is key—that’s probably how a misguided adaptation of Uncle Buck is making its way to the airwaves this summer. Fox has good reason to believe the nostalgia hype: One of its biggest hits last season was its six-episode reboot of The X-Files, which got great ratings with viewers young and old. It also capitalized on the show’s streaming resurgence (the original episodes are all available on Netflix) to get huge attention online, even though reviews were generally negative.

So this year Fox is bringing back 24 (though not in its classic 24-episode format) and Prison Break, as if to remind viewers of the mid-2000s when it was a champion of high-concept genre TV. The network’s also continuing its run of live musical spectaculars after the success of Grease Live, with The Rocky Horror Picture Show (starring Laverne Cox) due sometime this fall. The recurring theme across every major network is a bet on big brand names and must-see TV events that demand to be watched live. It seems to be working. According to advertising insiders, prices could spike this year after a long plateau, as a flurry of investments in digital advertising have yielded mixed results.

That’s why the Big Four are chasing down well-tested projects: Any griping about NBC’s shift away from bolder television can be easily countered by citing the network’s steadily improving ratings. The firing of ABC’s chairman Paul Lee, who took creative risks on low-rated shows like Galavant and American Crime, was a sad reminder that companies value consistent ratings over good reviews, but it was a defensible decision nonetheless. This year, ABC is doubling down on its biggest name—Shonda Rhimes—adding a loose Romeo & Juliet adaptation called Star-Crossed from the mega-producer of Scandal, Grey’s Anatomy, and How to Get Away With Murder.

For all the focus on reboots and spinoffs, that seems like the smartest middle ground: betting on smart creators who make memorable, bombastic dramas that demand to be watched as quickly as possible. Though it’s not exactly prestige TV, Fox’s Empire remains one of the most-watched shows among young viewers and consistently trends across social media any time it features a major twist (i.e. almost every week). It’s the perfect mix of network nostalgia and forward-thinking programming, taking a classic genre (the Dynasty-esque soap) and giving it a contemporary setting and a diverse cast. By contrast, this year’s upfronts mostly seem firmly mired in the past.

The Cultural Revolution's Legacy in China

When the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, it didn’t matter that future Chinese President Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun, was a veteran and leader in the Communist Revolution. He was a representative of the bourgeoisie that China needed to purge, Mao Zedong said. The elder Xi was jailed for 16 years, while the future president was sent to the countryside to grow up and perform hard labor, leaving his life as an intellectual to realize Mao’s revitalized vision of communism.

The 10-year period began May 16, 1966, as Mao inspired the country’s youth to turn on their parents and teachers, often violently. These so-called Red Guards targeted the elites who were driving the country toward capitalism. During that period, 16 million children, like Xi, were sent to the countryside, while top leaders who were perceived as being against the Communist Party were either jailed or killed.

While there is no official count for the number of people who died during that period, one scholar estimated the number as between 500,000 to 8 million, and the number of people persecuted in the tens of millions. As The New York Times describes:

During the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards targeted the authorities on campuses, then party officials and “class enemies” in society at large. They carried out mass killings in Beijing and other cities as the violence swept across the country. They also battled one another, sometimes with heavy weapons, such as in the city of Chongqing. The military joined the conflict, adding to the factional violence and killing of civilians. The pogroms even included cannibalization of victims in the southern region of Guangxi.

That period, which ended with Mao’s death in 1976, is a controversial part of China’s history, one that current top officials would rather look past than celebrate. Monday marks the 50th anniversary of that start of the Cultural Revolution and there is no official celebration or recognition from state media.

Xi, though rarely, has talked about the turbulent decade. Speaking to state-run CCTV in 2003, he said:

“In the past when we talked about beliefs, it was very abstract. I think the youth of my generation will be remembered for the fervor of the Red Guard era. But it was emotional. It was a mood. And when the ideals of the Cultural Revolution could not be realized, it proved an illusion.”

The anniversary leaves the Chinese government in a predicament. It clearly wants to look past what the Communist Party in 1981 said was “the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the party, the country, and the people.” It also wants to quell any concerns that China may be heading toward another Cultural Revolution.

That fear was highlighted earlier this month when a symphony played several “red songs” at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, celebrating the Communist’s Party’s socialist past. One of those songs was “Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman,” the anthem of the Cultural Revolution. “Mao Zedong Thought is the sun that forever shines,” reads one line of the song.

Though the party’s Central Committee quickly distanced itself from the performance, critics still said a group inside the country wants a return of the repressive period.

Xi has led a crackdown in recent years on dissent, censoring media and the Internet. He has also gone after civil society, giving security forces control over foreign non-governmental organizations that deal with human rights, public health, and education.

Like Mao during the Cultural Revolution, there’s also been an increase in Xi’s cult of personality, as his face dons the front page of newspapers and propaganda across the country. There are even pop songs that celebrate him.

Xi even gave himself a new title as Chinese military power grows and regional tensions increase with disputed islands in the South China Sea. In April, donning a camouflaged uniform, the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party also became the commander in chief of the joint battle command.

Meanwhile, Mao is still a celebrated as one of the key figures in Chinese history. On the 120th anniversary of Mao’s birth four years ago, Xi called him “a great patriot and national hero.” As The Sydney Morning Herald reports:

But 40 years on from his death, Mao remains central to the Communist Party's narrative of ruling legitimacy. His embalmed body lies in state in a mausoleum overlooking Tiananmen Square, while his portrait smiles over the Forbidden City and graces every Chinese banknote.

By Mao's own measure, the mass campaign was his greatest achievement after leading the Communists to victory over the Japanese and the Kuomintang government which was exiled to Taiwan.

The Chinese government’s actions today is eclipsed by the events of that 10-year period, but as Xi tightens his grip over the country, comparisons are being made with a dark period in China’s history.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower