Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 150

June 4, 2016

Muhammad Ali and Vietnam

Muhammad Ali’s stand against the Vietnam War transcended not only the ring, which he had dominated as the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world, but also the realms of faith and politics.

“His biggest win came not in the ring but in our courts in his fight for his beliefs,” Eric Holder, the former U.S. attorney general, said Saturday.

On March 9, 1966, at the height of the war, Ali’s draft status was revised to make him eligible to fight in Vietnam, leading him to say that as a black Muslim he was a conscientious objector, and would not enter the U.S. military.

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America,” he said at the time. “And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father. … Shoot them for what? How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

A little more than a year later, on April 28, 1967, Ali, then 25 years old, appeared in Houston for his scheduled induction into the U.S. military. He repeatedly refused to step forward when his name was called—despite being warned by an officer that he was committing a felony offense that was punishable by five years in prison and a fine of $10,000. His refusal led to Ali’s arrest and eventual conviction—though he stayed out of prison while his case was appealed. His license to box was suspended in New York the same day, and his title stripped; other boxing commissions followed. Ali was unable to obtain a boxing license in the U.S. for the next three years.

The remarks and actions were even more controversial than the former Cassius Clay’s conversion to Islam in 1964. The Vietnam War was popular at the time in the U.S., and the sight of man, especially a black man, who not only refused to serve—but did so eloquently—incensed the sporting, media, and political establishments. Ali instantly became a national pariah—perhaps the most hated man in the country, as can be evinced in this monologue from David Susskind, the American television host, who was addressing Ali: (The link itself is worth following for Susskind’s obvious antipathy toward the man on the television screen.)

I find nothing amusing or interesting or tolerable about this man. He’s a disgrace to his country, his race, and what he laughingly describes as his profession. He is a convicted felon in the United States. He has been found guilty. He is out on bail. He will inevitably go to prison, as well he should. He is a simplistic fool and a pawn.

Nor was Susskind the only man, nor whites alone in opposing Ali’s actions: Jackie Robinson, the first black man to play in the major leagues, said Ali’s stand was hurting African Americans who were, unlike him, fighting in Vietnam.

“He’s hurting, I think, the morale of a lot of young Negro soldiers over in Vietnam,” Robinson said. “And the tragedy to me is, Cassius has made millions of dollars off of the American public, and now he’s not willing to show his appreciation to a country that’s giving him, in my view, a fantastic opportunity.”

Ali, though, didn’t see it that way: “I would like to say to those of the press and those of the people who think that I lost so much by not taking this step, I would like to say that I did not lose a thing up until this very moment, I haven’t lost one thing,” he said. “I have gained a lot. Number one, I have gained a peace of mind. I have gained a peace of heart.”

Still, Ali’s continued refusal to go to Vietnam—despite repeated pressure—coincided with the war’s growing unpopularity in the U.S. And in the three years he didn’t fight, Ali became a prominent speaker at college campuses across the U.S., as the anti-war movement grew in strength, silencing those who told him to participate with his compelling arguments:

Eventually, state boxing commissions did grant Ali licenses to fight. And when he returned to the ring, on October 26, 1970, he knocked out Jerry Quarry in the third round. The road to legal exoneration took longer. My colleague Matt Ford explains what happened:

When Ali appealed his case to the U.S. Supreme Court for the final time in 1971, liberal stalwart Justice William Brennan convinced his colleagues to hear the case. Justice Thurgood Marshall recused himself because he had been solicitor general when Ali was prosecuted. That left eight justices, who on a first vote sided with the Justice Department in a 5-3 decision.

Ali claimed he qualified for conscientious-objector status because he opposed the war as a black Muslim. The Justice Department challenged that status, citing his statements that he would fight the Vietcong in a “holy war” if they fought Muslims. The justices began drafting their opinions when one of Justice John Marshall Harlan II’s clerks convinced him to take home Elijah Muhammad’s Message to the Blackman in America. Harlan returned to the Court the next day and, convinced of Ali’s sincerity after reading the text, switched sides.

Harlan’s move raised the prospect of a 4-4 split, which would preserve Ali’s conviction and send him to jail without explaining why. The justices instead chose to resolve it on narrow technical grounds and unanimously vacated the conviction.

Ali triumphed, but his victory came at great personal cost. As Angelo Dundee, his trainer, said Ali’s beliefs cost him “the best years of his life.” Before he was prevented from fighting, “it seemed impossible to hit him,” he said. The man who returned to the ring “was more flat-footed.”

“Nevertheless, he was so great that he still was the best among all of his opponents, which is something that must be taken into account when talking about Ali,” Dundee said. “He was robbed of his best years, his prime years.”

Ali once proudly declared: “I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me—black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own. Get used to me.”

President Obama, in his remarks Saturday on Ali’s death, echoed those sentiments and spoke of the personal cost of the champion’s stance during the Vietnam era.

“It would earn him enemies on the left and the right, make him reviled, and nearly send him to jail,” Obama said. “But Ali stood his ground. And his victory helped us get used to the America we recognize today.”

Feed the Beast: A Hot Mess of a Restaurant Drama

Feed the Beast, AMC’s new drama about two friends compelled by fate, financial ineptitude, and dramatic necessity to open a restaurant in New York, is a lot of things, but it isn’t afraid of metaphor. There’s its title, for one thing, which contains multitudes (but could also possibly be overworked TV writers making a point). There’s the way scenes are punctuated with close-up shots of flames being ignited. Most of all, there are the show’s parallels between food and addiction: the perpetual sniffing of a coked-up chef versus the exaggerated inhalations of a sommelier, the butcher who doubles as a drug dealer, the sense that being a restaurateur, like being an addict, is something you never recover from.

That it’s not a good show is clear fairly early in the first episode, but it is occasionally an interesting one. Tommy (David Schwimmer) is a widower struggling to raise his son after his wife was killed in a car accident, who’s declined from being an advanced sommelier to an alcoholic wine salesman. Dion (Jim Sturgess) is Tommy’s childhood best friend, a brilliant chef fresh out of jail who’s also a stupidly reckless cocaine addict in trouble with the mob. There are questions the show fails to answer right off the bat: Why does Tommy live in a vast empty warehouse? Why would anyone agree to do anything for or with Dion, a violent lunatic who burned down his last restaurant on purpose? Why is every primary adult character in a show set in the Bronx white? Answers are sacrificed in Feed the Beast’s quest to be 18 different things at once: a Bourdain-esque tale of bad-boy chefs made good, a gritty crime drama, a superhero show, a touching tale of familial reception.

For the viewer at least, it’s exhausting. In the first four episodes, Schwimmer and Sturgess operate on totally different levels, with Schwimmer adding subtle pain to the sad-sack befuddlement he mastered earlier this year playing Robert Kardashian in The People v. OJ Simpson, and Sturgess using every over-the-top affect he can to make Dion annoying (brash accent, overbearing machismo, pathological sniffing and wheezing). Apparently appearing in a different show altogether is Mad Men’s Michael Gladis as Patrick Woichik, a gangster known as the Tooth Fairy for his habit of extracting people’s incisors. The character feels like Feed the Beast’s attempt to bring some Marvel-lite villainy to proceedings (Gladis plays the Tooth Fairy like a subdued version of Daredevil’s Kingpin), but his looming presence in an armchair in the back of a Mercedes van only ever feels absurd.

Feed the Beast is based on a Danish show, Bankerot, with Dexter’s Clive Phillips as showrunner and Bankerot’s Henrik Ruben Genz and Malene Blenkov on board as executive producers. This, along with its parent network, perhaps explains the maddening tonal inconsistency: It has all the performative dour masculinity of an AMC drama, but also moments of pure Scandinavian realism. Tommy’s relationship with his son, TJ (Elijah Jacob), who’s refused to speak since his mother died, is one of the show’s highlights. His relationship with Pilar (Lorenza Izzo)—a magical widow who meets Tommy in his grief-counseling group but seems blithely and cheerily unaffected by the death of her husband, and mostly functions so Tommy and Dion can explain the intricacies of fine dining to a haute-cuisine rube—is not.

Then there’s the dialogue. “Now we nose the wine,” Tommy tells Pilar. “That’s wine jargon. Smell it.” Later, after he’s described the history of his friendship with Dion, she remarks, “You guys punch each other in the dick a lot,” to which he responds, totally straightfaced, “We do. We’re friends.” Clearly, Phillips has invested heavily in getting the details of the restaurant industry right—Sturgess went to cooking classes, and AMC brought in the chef Harold Dieterle as a consultant to make the food scenes authentic. That they couldn’t finesse the script a little more is a pity, but it wouldn’t have saved a show that can’t figure out whether its spirit animal is August Escoffier or Guy Fieri.

Embracing the Greatest

I do not remember much of Muhammad Ali’s life firsthand. The sharpest memories that come to me are of the middle-aged man, slowed and bowed by a crippling disease, who lit the flame at the ‘96 Olympics in Atlanta. Part of my life has been spent watching Ali’s in reverse; watching his godlike physique and hellfire oratory return, trying to figure out just how the figure of dignified defiance, one whom my elders treated with utmost deference, had been forged.

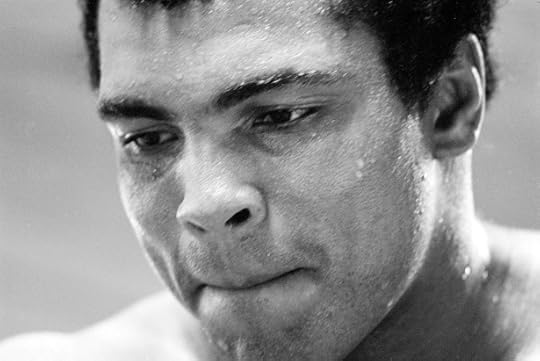

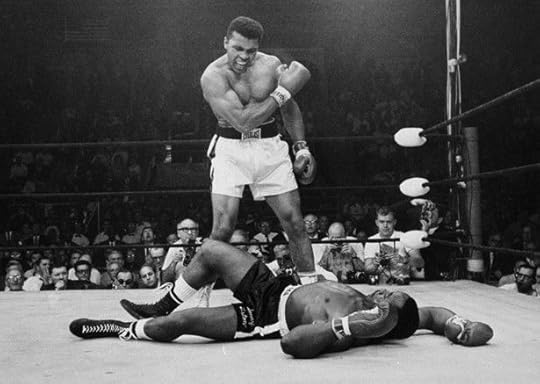

The photograph of his stunning upset knockout of Sonny Liston in 1964––the greatest sports photo of all time––hung over the wall of my uncle’s bedroom. In summers at my grandmother’s house, I would take his poster, taking care to roll it up just right, and pin it to my own bedroom wall with a handful of multicolored tacks. He watched over me in my sleep, and during the day I listened to old records, interviewed family members, and read and watched what I could of the past. My question then was simple, but dictated how and on what terms I came to appreciate him: Who was Muhammad Ali?

Maybe the first answer is that the person we knew as Muhammad Ali was a gestalt of identities. There was the dominating youthful warrior-poet, his most enduring mode, who floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee, and who rumbled until he was no longer a young man. Then there was the leather-tough veteran, a rope-a-doping, slippery, taunting tower of a man. There was the philosopher, the warrior, the conscientious objector, the firebrand, the Black Power icon, and the nonviolent pacifist. There was the man who rejected his “slave name” and scrutinized other black people for not doing the same. There was the elderly man who condemned Donald Trump’s contempt for Islam. There was the patriot, the exile, the Nation of Islam sectist, the Sunni, the father, the brother, the husband, and the ex-husband. There was Cassius Clay, Baptist chrysalis, and then Muhammad Ali, Muslim man. He contained multitudes.

Each of those identities was welded together, though, by Ali’s enduring love for and contemplation of blackness. Ali’s idea of blackness––not merely a skin color or ancestry, but a resistance to white supremacy itself––without an iota of apology was part of his beauty, as George Foreman’s heartbreaking Twitter memorial remembers. But it was also existentially dangerous. There were death threats and jeers. After Ali was made eligible for the draft in 1966, he was convicted and sentenced to prison for his refusal on religious and racial grounds. He was stripped of his boxing license and his passport and essentially exiled for his resistance. His response was defiant. “They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn't put no dogs on me, they didn't rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father,” Ali said of the Vietcong. “Shoot them for what? How can I shoot them poor people?”

Ali was one of the greatest boxers of all time, no doubt, but I’ve found his true skill to be his role as a public intellectual, expressing his unapologetic blackness in the face of life-threatening danger. He bridged the old gap between disparate branches of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, embracing Malcolm’s religion while veering closer to King’s vocal anti-war nonviolence. He was a face of the Black Power movement and inspired organizations such as the Black Panthers and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Perhaps more than anyone, Muhammad Ali provided the public voice for a race seeking to move forward in movement after losing King in 1968.

That voice reverberates today. Even in death, Muhammad Ali is everywhere. He is in Mike Tyson’s fast-talking menace. He is in Michael Jordan’s singular greatness and arrogance. He is in Russell Westbrook’s scowl, Steph Curry’s public religiosity, and Cam Newton’s smile. He is in Serena Williams’s dominance. He is in President Obama’s swagger. He is in hip-hop; his quotes have been pretty much the bedrock for the art’s boasts of masculinity. His anti-war stance, racial philosophy, and confrontation as praxis are directly evident in black millennial protest today. Fanciful a thought as it may be, I like to envision that some of him speaks through me as well.

Understanding Ali is vital in figuring out how to honor him. He was a man who stood against a racist and militarist state. It is not possible for warmongers to celebrate him in good faith, nor it is possible for a man who threatens to ban Muslims from entering the country to do so. It is not possible for people who condemn Serena Williams for arrogance to fairly eulogize Ali. It is not possible for those who are “colorblind” or see blackness as a thing to be “transcended” to truly see a man who saw his blackness as a central and enduring part of his identity. And it is not possible for those turn a blind eye to America’s white supremacist sins to truly ponder the greatness of the Greatest.

To embrace Muhammad Ali is to embrace a radical, a man of contradictions and convictions who would still not be looked on kindly today if his rise and rhetoric were repeated. It is to grapple with arrogance as a therapy; with resistance as a default mode. Embracing him is embracing his multitudes.

American Ninja Warrior and Hustlers: The Week in Pop-Culture Writing

Is American Ninja Warrior the Future of Sports?

Jason Gay | Wall Street Journal

“American Ninja Warrior has earned that 21st-century buzzy buzzword, relevance, and it made me wonder if there was something about this wacky obstacle-course show that could be applied to older games to make sure they thrive in the future. What if legacy sports just need some ninja lessons?”

Requiem for a Hustler

Justin Tinsley | The Undefeated

“At its most powerful, rap is a series of artists detailing the battle zones many called home. The poverty, and the soundtrack of gunshots in Brooklyn’s Marcy Housing Projects when he was growing up, when he was surviving and manipulating situations during the crack-cocaine era—all of that, even now as we see him on yachts and such, stays with him. A recurring symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder is flashbacks, and Jay Z’s cocaine dreams are, in their own way, his version of PTSD. Working through it is a lifelong process.”

Inside the BeyHive

Alyssa Bereznak | The Ringer

“The BeyHive is massive — more than 17,000 members strong, and that’s just the active participants on the forum, not the hangers-on (one must apply for access to the group). But the club’s intense organization and tactical offense suggest it is a well-oiled machine. So how does such a huge, entirely remote body move with such precision, and what technology does it use to do so?”

Fandom Is Broken

Devin Faraci | Birth Movies Death

“But there’s something else going on now. Once upon a time the over-identification was between the fan and the creator—it’s why so many celebs get stalked ... The corporatized nature of the stories we consume has led fans—already having a hard time understanding the idea of an artist's vision—to assume almost total ownership of the stuff they love.”

The Clique Imaginary

Alana Massey | The New Inquiry

“‘Clique-y’ is the pejorative used to describe young women in a friend group that is perceived to be exclusionary. But this dismissal dehumanizes them and disregards their personal reasons for maintaining a tight-knit circle of friends. The suspicion aimed at cliques targets female intimacy, particularly when it shared between women with social capital.”

We R Cute Shoplifters

Tasbeeh Herwees | Good

“Like the original Bling Ring—immortalized in the 2013 Sofia Coppola film of the same name—Tumblr’s lifters captivated outsiders not just because they were criminals but because they were, purportedly, teenage girl criminals. The effeminate nature of their crimes—the stolen lipsticks and bras, purses and panties—as well as the exhibition of their criminality online lent a glamour to what they did.”

Actually, Criticism Is Literature

Jonathan Russell Clark | Lithub

“Critics have struggled to develop their voices and dealt with the same humbling critiques of their work that they offer to others. They are—if my point’s not hitting home—just like the people they write about. In fact they are so similar that the gap between critic and non-writer is much more substantial than that between critic and artist.”

Surrendering

Ocean Vuong | The New Yorker

“I had read books that weren’t books, and I had read them using everything but my eyes. From that invisible ‘reading,’ I had pressed my world onto paper. As such, I was a fraud in a field of language, which is to say, I was a writer. I have plagiarized my life to give you the best of me.”

All the Songs Are Now Yours

Dan Chiasson | The New York Review of Books

“In fact, ‘listening’ was not enough; Copland wanted his readers to ‘listen for’ what he called the ‘sound stuff’ of music: to clear the mind not only of external distractions and mental obstacles, but of all nonessential sonic wadding that surrounded it. Music required targeted attention, the state of mind you might enter when doing a word-find or watching, through binoculars, for a migratory bird.”

The Tributes to Muhammad Ali

Updated on June 4 at 11:01 a.m. ET

He stood with leaders, was adored by the common man, became arguably the most famous face of the 20th century, and when Muhammad Ali died Friday at age 74, the tributes poured in from as far afield as Louisville, Kentucky, where he was born in 1942 and the Philippines where he fought one of his most stories contests.

“The values of hard work, conviction and compassion that Muhammad Ali developed while growing up in Louisville helped him become a global icon,” said Greg Fischer, the Louisville mayor. “As a boxer, he became The Greatest, though his most lasting victories happened outside the ring.” Flags in Louisville will fly half-staff to honor Ali.

Ali’s influence, as Fischer pointed out, was felt far outside the ring. He was an important voice during the civil rights era and became an icon for the movement against the Vietnam War in which he refused to fight, saying: “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on Brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?”

That stand earned him much disdain at the time, as well as cost him his heavyweight title and, in his words, millions of dollar, but it’s a position for which he was ultimately vindicated.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the NBA great, said Ali’s willingness to “stand tall and fight for what he believed was right” came during an era where many African Americans who spoke about injustice “were labelled uppity and often arrested under one pretext or another.” Ali’s stand, he said, “made all Americans, black and white, stand taller.”

“I may be 7ft 2in,” Abdul-Jabbar wrote on Facebook, “but I never felt taller than when standing in his shadow.”

The tributes from the world of boxing reflected the status of the man dubbed The Greatest of All Time.

Floyd Mayweather, the current five-division boxing champion, said on Instagram:

A photo posted by Floyd Mayweather (@floydmayweather) on Jun 4, 2016 at 12:00am PDT

And Mayweather’s rival, Manny Pacquiao, the Filipino boxer, said: “We lost a giant today. Boxing benefitted from Muhammad Ali’s talents but not nearly as much as mankind benefitted from his humanity.”

Mike Tyson, who dominated the sport a decade after Ali, wrote:

God came for his champion. So long great one. @MuhammadAli #TheGreatest #RIP pic.twitter.com/jhXyqOuabi

— Mike Tyson (@MikeTyson) June 4, 2016

And George Foreman, Ali’s rival in the Rumble in the Jungle said he, Joe Frazier, and Ali “were 1 guy. A part of me slipped away. The greatest piece.”

It's been said it was Rope a dope, Ali beat me with no his beauty that beat me. Most beauty I've know loved him pic.twitter.com/G64WX3eyZC

— George Foreman (@GeorgeForeman) June 4, 2016

Don King, the boxing promoter behind some of Ali’s biggest fights, including the “Rumble in the Jungle” and the “Thrilla in Manila,” told Fox News: “Ali will never die. He was a fighter for the people and to become a champion of the people he demonstrated the type of character he was.”

The stars of the NBA, NFL, soccer, and entertainment paid their tributes, as well—as did those from the world of politics. President Obama reiterated what Ali himself knew: that the champ was the greatest. But the president added:

In my private study, just off the Oval Office, I keep a pair of his gloves on display, just under that iconic photograph of him – the young champ, just 22 years old, roaring like a lion over a fallen Sonny Liston. I was too young when it was taken to understand who he was – still Cassius Clay, already an Olympic Gold Medal winner, yet to set out on a spiritual journey that would lead him to his Muslim faith, exile him at the peak of his power, and set the stage for his return to greatness with a name as familiar to the downtrodden in the slums of Southeast Asia and the villages of Africa as it was to cheering crowds in Madison Square Garden.

“I am America,” he once declared. “I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me – black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own. Get used to me.”

That’s the Ali I came to know as I came of age – not just as skilled a poet on the mic as he was a fighter in the ring, but a man who fought for what was right. A man who fought for us. He stood with King and Mandela; stood up when it was hard; spoke out when others wouldn’t. His fight outside the ring would cost him his title and his public standing. It would earn him enemies on the left and the right, make him reviled, and nearly send him to jail. But Ali stood his ground. And his victory helped us get used to the America we recognize today.

Here’s the statement from Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee:

Muhammad Ali is dead at 74! A truly great champion and a wonderful guy. He will be missed by all!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 4, 2016

Former President Clinton in a statement said he and his wife, Hillary Clinton, the Democratic presidential candidate, “are saddened by the passing of Muhammad Ali.”

“From the day he claimed the Olympic gold medal in 1960, boxing fans across the world knew they were seeing a blend of beauty and grace, speed and strength that may never be matched again,” Clinton said.

Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton’s rival for the Democratic nomination, called Ali the “greatest, not only an extraordinary athlete but a man of great courage and humanity.”

Asked once about how he’d like to be remembered, Ali replied: “I would like to be remembered as a man who won the heavyweight title three times, who was humorous and who treated everyone right. As a man who never looked down on those who looked up to him...who stood up for his beliefs...who tried to unite all humankind through faith and love.

“And if all that's too much, then I guess I'd settle for being remembered only as a great boxer who became a leader and a champion of his people. And I wouldn't even mind if folks forgot how pretty I was.”

Muhammad Ali (1942-2016) achieved that and far more. A funeral will be held in Louisville, where the city will hold a memorial service on Saturday.

June 3, 2016

Remembering Muhammad Ali, the Greatest of All Time

Muhammad Ali, the fleet-footed, trash-talking, butterfly-floating, bee-stinging heavyweight boxing champion of the world, died Friday evening. He was 74.

The cause of death was a respiratory illness aggravated by Parkinson’s disease, the debilitating affliction from which he suffered in the latter decades of his life.

Provocative, polarizing, and passionate, Ali rose to the upper strata of the boxing world in the turbulence of the 1960s, claiming the heavyweight title in 1964. But his conscientious refusal to serve in the Vietnam War led to his criminal conviction on draft-evasion charges and the stripping of his title.

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously reversed his conviction, and Ali returned to the ring. He reclaimed the title in 1974 against Big George Foreman in the legendary Rumble in the Jungle in Zaire, then went on to defend it against Smokin’ Joe Frazier in the Thrilla in Manila in 1976. As age and illness steadily took their toll, Ali retired for the fourth and final time in 1981.

A full obituary will follow.

Muhammad Ali Is Hospitalized

Muhammad Ali, the former boxing heavyweight champion, is battling respiratory issues at a hospital in the Phoenix area. He is 74 years old, and his condition is complicated by the Parkinson’s disease with which he was diagnosed in the 1980s.

The Associated Press, citing two anonymous sources whom it identifies as people familiar with Ali’s condition, reported the boxing legend’s “condition .. may be more serious ... than his previous hospital stays.” Bob Arum, the boxing promoter, told ESPN: “I know it’s not looking good. He’s a fighter and he’s going to continue to fight.” NBC News, meanwhile, reported the boxer was in “grave” condition, adding his family has gathered by Ali’s bedside.

Ali was admitted to hospital on Thursday. At the time, Bob Gunnell, his spokesman, said the boxer’s condition was fair and that the hospital stay was short. On Friday, he told the AP there was no update on Ali’s condition. Ali previously spent multiple days in hospital in January 2015.

Reaction to Ali’s hospitalization led to wishes for his speedy recovery from his fellow boxers:

Prayers & blessings to my idol, my friend, & without question, the Greatest of All Time @MuhammadAli ! #GOAT

— Sugar Ray Leonard (@SugarRayLeonard) June 2, 2016

Our Prayers and thoughts are with @MuhammadAli and his family #AliBomaye

— Amir Khan (@amirkingkhan) June 3, 2016

Why Is Donald Trump So Angry at Judge Gonzalo Curiel?

Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee for president, escalated his unprecedented verbal attacks on Federal District Judge Gonzalo Curiel on Thursday night. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Trump claimed the judge could not fairly preside over the Trump University cases because of Curiel’s “Mexican heritage.” (Curiel is from Indiana; his parents are Mexican immigrants.) “I’m building a wall, it’s an inherent conflict of interest,” he added.

Read Follow-Up Notes

Watch Trump repeatedly call Curiel a Mexican on CNN; Fallows reacts

As my colleague David Graham noted, there’s no precedent for judges to recuse themselves from a case because of their race, gender, faith, or sexual orientation. Trump’s racist remarks follow speeches in which the candidate said he was being “railroaded” by a “rigged” legal system. He simultaneously singled out Curiel as “hater of Donald Trump,” called him a “disgrace,” said he should “be ashamed of himself,” and said other federal judges “ought to look into Judge Curiel.”

Corrosive personal attacks aren’t new behavior for the presumptive Republican nominee. But unlike other targets of Trump’s ire, Curiel cannot defend himself in any forum. He acknowledged in an order last Friday that Trump had “placed the integrity of these court proceedings at issue,” but will almost certainly go no further than that observation. Curiel is bound by the judicial code of ethics, which says that federal judges “should not make public comment on the merits of a matter pending or impending in any court,” including their own. The code also says judges “should not be swayed by partisan interests, public clamor, or fear of criticism.”

That would suffice in almost any other circumstance. A judge’s orders and rulings are in the public record; those writings can speak for themselves. But Trump is more than the typical scorned defendant. His accusations against Curiel’s integrity are serious, the platform from which he hurls them is massive, and he seems unwilling to relent in making them. A growing chorus of American legal scholars from the left, right, and beyond says his remarks threaten the rule of law.

The real-estate businessman also has another problem: There’s no evidence whatsoever in the public record to support Trump’s claims about Curiel.

We’ll start at the beginning. Curiel is presiding over two separate class-action lawsuits about Trump University. One of them, Low v. Trump University, was filed in April 2010 under the name Markaeff v. Trump University. The other, Cohen v. Trump, was filed in October 2013. (A third case brought by New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman in 2013 is also under way in that state.) Trump is named as a defendant in both cases.

The plaintiffs in Low and Cohen portray Trump University as a basically fraudulent endeavor, one that promised Trump’s secrets to real-estate success but instead dispensed generic advice for tens of thousands of dollars. They’ve amassed a collection of evidence and testimony that seems to support their claims. Trump strongly denies the allegations and often cities numerous positive testimonials the seminars received from former customers of Trump University.

In his public remarks, Trump appears to make no distinction between Low and Cohen. But there are crucial differences between the two civil class-action lawsuits. The Low plaintiffs sued Trump University and Trump himself under various consumer-protection laws in California, Florida, and New York—a relatively standard class-action lawsuit.

Cohen, on the other hand, targets Trump through a provision of the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, more commonly known as the RICO Act—the same statute federal prosecutors use to bring down mob bosses. In essence, Low accuses Trump University of engaging in fraudulent business practices, while Cohen frames Trump University itself as a criminal enterprise with Trump as the orchestrator of a racketeering scheme.

As you can imagine, Trump strongly opposes that characterization. In a motion for summary judgment in Cohen filed in March, he condemned the “pervasive abuse of civil RICO” that he says the case represents. “Indeed, if this case is allowed to proceed, it would represent an unprecedented and unprincipled expansion of civil RICO and transform virtually every alleged violation of consumer protection laws into a civil RICO claim,” Trump argued.

Beyond Curiel’s ethnicity, Trump’s most specific grievance against the judge is that he wrongly denied summary judgment in Trump’s favor. This assertion is only partially accurate. Trump asked Curiel for it separately in each case, filing the motion for Low in February 2015 and for Cohen in March 2016. The Cohen motion is still pending, with a hearing scheduled for July 18. Trump’s frustration likely springs from Curiel’s ruling against him last November on most of the Low summary-judgment motion.

Summary judgment is granted when both sides in a case agree on the facts. Under those circumstances, a jury trial becomes pointless since there aren’t any factual disputes for jurors to deliberate and resolve. The judge’s role when addressing a summary-judgment motion is to determine whether there are any factual disputes.

In Low, the plaintiffs’ case centers on three misrepresentations allegedly made to them by Trump and Trump University: “(1) Trump University was an accredited university; (2) students would be taught by real estate experts, professors and mentors hand-selected by Mr. Trump; and (3) students would receive one year of expert support and mentoring.”

When asking for summary judgment, Trump said he did not personally make these claims to the customers and never entered into any contracts with them. Therefore, he argues, he isn’t liable for them under state consumer-protection laws. The plaintiffs countered they were persuaded to purchase Trump University products by promotional videos featuring Trump and by print advertisements bearing his image and assertions about the program’s quality. Curiel denied the motion.

“Based on the foregoing, the Court concludes that Plaintiffs have raised a genuine dispute of material fact as to whether Mr. Trump can be personally liable for the alleged misrepresentations and misconduct,” Curiel wrote about one of Trump’s assertions. “For example, Plaintiffs have provided evidence that Mr. Trump reviewed and approved all advertisements. These advertisements included the alleged core misrepresentations, such as that Mr. Trump ‘hand-picked’ the instructors and mentors.”

This doesn’t mean Curiel sided with the plaintiffs on the facts of the case. It means that Curiel determined a factual dispute existed between Trump and the plaintiffs—nothing more, nothing less. He therefore denied summary judgment so a jury could weigh the evidence offered by each side and determine the facts of the case from it. Trump may not like Curiel’s decision, but it’s neither a surprising nor an egregious one.

Some Trump supporters have also criticized Curiel’s May 27 order to unseal some of the Trump University internal documents in the case. Those criticisms also seem to lack merit. Curiel’s order came in response to a public-interest motion filed in April by the Washington Post. The public is presumed to have the right to access court documents barring “compelling reasons” to keep them sealed, but Trump argued against their release by citing the existence of trade secrets within the internal “playbooks.”

After a line-by-line review, federal magistrate judge William Gallo found that “in isolation, nothing appears to be unique, proprietary, or revolutionary” about the documents. He also noted that the 2010 Trump University Playbook, which shared a large portion of its contents with the other documents, had already been made public two years ago. (The Atlantic even wrote at length about their contents in 2014.) Curiel agreed with Gallo’s findings and ordered the documents released with some redactions at around 12:40 p.m. local time. Trump launched a verbal tirade against Curiel at a rally across town later that night.

In short, if Curiel is a “hater of Donald Trump,” there is no evidence of it in this case. There’s nothing unusual or suspicious about his rulings so far in the lawsuits. While Curiel has allowed the case to proceed to trial, he has granted Trump some partial victories along the way on the size and scope of the cases. And instead of letting the trial unfold alongside Trump’s bid for the White House, Curiel delayed its start until after the election.

Indeed, what’s not in the public record is telling. Trump has publicly complained about Curiel since at least 2014, when one of his lawyers claimed Trump would ask Curiel to recuse himself based on his alleged (and unspecified) “animosity toward Mr. Trump and his views” after Curiel rejected his motion for dismissal. Almost two years later, no motion for recusal can be found on the docket of either case, then or now.

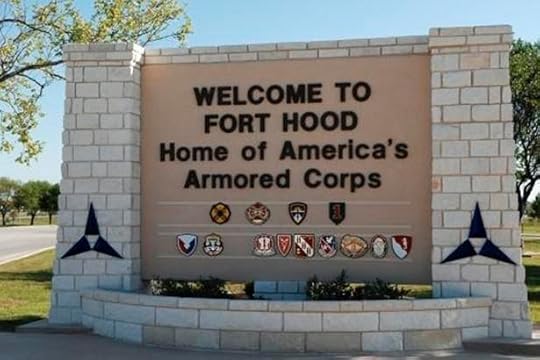

Texas Floods: Nine Fort Hood Soldiers Are Dead

Updated on June 3 at 8:30 p.m. ET

The death toll from the floods in Texas that swept away a truck carrying a dozen soldiers from Fort Hood has risen to nine, after the bodies of the four missing soldiers was recovered Friday evening.

BREAKING: Army says bodies found of four missing Fort Hood soldiers who were swept away in rain-swollen creek.

— The Associated Press (@AP) June 4, 2016

Earlier in the day, rescue workers found the bodies of two other soldiers who were on the truck. The search began after a 2 ½-ton truck carrying a dozen soldiers overturned Thursday while crossing Owl Creek, which had been flooded because of the heavy rains that have hit Central Texas recently.

Right now @Owl Creek Park. Search continues for missing soldiers. Hear from agencies assisting recovery on @KCENNews pic.twitter.com/32OGFTXJpW

— Amanda del Castillo (@AmandaDTV) June 3, 2016

The soldiers had tried to cross part of Owl Creek, about 12 miles north of Forth Hood. Three soldiers found alive shortly after the accident were taken to the hospital on Fort Hood.

More than half of Texas is under flood watch as rains have caused rivers and reservoirs to overflow. It’s not clear exactly how the truck overturned, but a spokesman for the Army post told the Austin American-Statesman the soldiers were in the proper place, and doing what their training exercise called for.

The Secret Bonus Pool For FIFA’s Top Leaders

A group of top leaders in FIFA paid themselves tens of millions of dollars in secret bonuses and salary increases, according to contracts that investigators revealed Friday.

Three people at FIFA, the organization that governs global soccer, have been implicated for hiding bonuses they approved for one another, totaling nearly $80 million. They are former FIFA President Joseph Blatter, former Secretary General Jérôme Valcke, and former Chief Financial Officer Markus Kattner, who also served as deputy secretary general. All three men have either been suspended or fired from the organization.

The news comes just a day after Swiss police raided FIFA’s offices in Zurich. With this evidence, the three men are accused of approving bonuses for each other, then hiding the evidence of those payouts in a bonus pool, as The Wall Street Journal reported:

A person familiar with the investigation said the payments were concealed in FIFA’s financial results as part of a general bonus pool, without any details on who might be receiving them or the specific amounts.

Their existence was also kept hidden from all but a few senior officials at FIFA, all of whom had the power to approve them for each other, people familiar with the investigation said.

According to a statement released on FIFA’s website, the payouts took place from 2011 until 2015. The contracts that revealed the financial details were found in a safe in Kattner’s office at FIFA, the Journal reported.

FIFA said it would share the results of its internal investigation with the Swiss Attorney General’s Office, and with the U.S. Department of Justice, which indicted top FIFA officials last may on charges of racketeering, conspiracy, and corruption. That led to the arrest of several top FIFA officials at a hotel in Zurich the same month. Since then, FIFA has been in turmoil, as its own investigation reaches deeper into corruption at the very top levels of the organization.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower