Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog, page 124

July 11, 2016

The Pokémon Go Armed Robbery

NEWS BRIEF Teens and nostalgic millennials have spent the past few days losing their minds over the reincarnation of Pokémon, the classic game and cartoon from the early 2000s, as a new mobile app that allows them to catch ’em all. But a handful of users in Missouri found another, more sinister purpose for the app over the weekend.

At about 2 a.m. Sunday, police in the city of O’Fallon responded to a report of an armed robbery. They arrested four people in connection with the crime, confiscated a handgun, and learned the suspects had used Pokémon Go to lure their victims. The O’Fallon Police Department described the robbery in a Facebook post, which quickly confused readers.

“Many of you have asked how the app was used to rob victims, the way we believe it was used is you can add a beacon to a pokestop to lure more players,” the department wrote in an update to its post. “Apparently they were using the app to locate ppl [sic] standing around in the middle of a parking lot or whatever other location they were in.”

What?

Let’s start with what Pokémon Go is: It’s a free app for iOS and Android devices, developed by California-based Niantic. It was released last week in the United States, Australia, and New Zealand and quickly rose to the top of Apple’s free apps list. So many people were using it in its first few days that its servers crashed repeatedly.

Players exist as avatars, and to move those avatars around in the game, they have to walk around in the real world—through their homes, offices, city streets, anywhere—traveling across the land, searching far and wide. Pokémon Go uses GPS to figure out where players are. Eventually, a wild Pokémon appears. And this is the part that has people squeeing with joy: When players encounter a Pokémon on screen, they can choose to see it in augmented reality. The app taps into the phone’s camera, and the character is shown against the backdrop of the real world. Players can then “photograph” the Pokémon. To capture it, chuck a Pokéball at it.

As for how the suspects in the Missouri armed robbery might have used the app to their advantage, let’s go to Bryan Menegus at Gizmodo, who explains the app’s GPS-related features:

Aside from wandering around to catch monsters, the game involves walking to “gyms” and “PokéStops”, which are where Pokémon battle each other and where items are collected, respectively. Gyms and PokéStops are supposed to be linked to local landmarks. The trouble is that Niantic imported these “landmarks” from their earlier game, Ingress, where those locations were created and tagged by players, and seemingly never reviewed before becoming an integral element of a game for children.

Menegus says the app has led players to some strange places, including strip clubs and cemeteries. On Thursday, the app led a teenager in Wyoming to a bridge, where she discovered a body face down in the river below it.

Pokémon Go could also lead to injury, if some players are not careful. Mike Schultz, a 21-year-old from New York, told the AP last week he fell off his skateboard while using the app and cut his hand on the sidewalk. “I just wanted to be able to stop quickly if there were any Pokémons nearby to catch,” he said. “I don’t think the company is really at fault.”

Back in O’Fallon, Missouri, police have identified and released the mug shots of three adult male suspects in the armed robbery. They have been charged with first-degree robbery and armed criminal action.

One Secret Ingredient of Great B-Movies

Small talk, many argue, is the worst—a tedious practice that makes personal encounters shallow. In January, an actuary named Tim Boomer wrote a Modern Love column in The New York Times that waxed lyrical about the joyful possibilities of abandoning the custom altogether. Others disagree: Slate’s Ruth Graham argued in February that conversational pleasantries aren’t only necessary, but can also be enjoyable and quite revealing.

Whatever side of the debate you fall on, it’s difficult to ignore the uniquely American dimensions of small talk. In the 19th century, Alexis de Tocqueville marveled at how citizens of the young country could talk so much without really saying anything. Last week, Karan Mahajan wrote in The New Yorker about how it took him a decade to master the kind of culturally mandated casual friendliness that Americans expect in places like shops or restaurants. And as anyone who’s worked in the U.S. knows, office chit-chat is an unavoidable part of professional life.

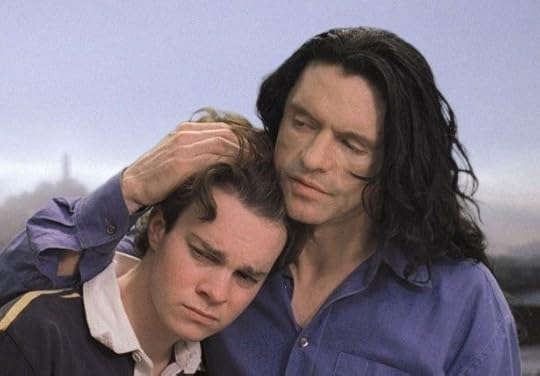

It’s no surprise then, that small-talk culture has been thoroughly depicted in American motion pictures—particularly in cult movies written and directed by foreign filmmakers. Works such as The Room, Birdemic: Shock and Terror, and Samurai are regular entries on lists of the best bad movies ever made, thanks in part to their logic-defying plots, risible acting, terrible scripts, and enthusiastic fan bases. But much of their subtler charm comes from how they capture—in bizarre, messy fashion—the contradictory nature of American small talk as a phenomenon that’s at once gloriously mundane and necessary to human connection.

You could dismiss the peculiar dialogue of these movies as a direct consequence of the filmmakers’ inexperience with the English language or screenwriting itself. But plenty of works exist to prove that being a native speaker or veteran writer isn’t an obstacle to bad writing. The appeal of these particular B-movies, rather, lies in the filmmakers’ strenuous efforts to overcome not just a linguistic barrier, but also a fundamentally cultural one. In daily American life, small talk is at best a mindless, learned habit; at worst, it’s evidence of a vapid society. But filtered through an outsider perspective, this social nicety—intended to be, well, nice and unobtrusive—becomes something horrible, conspicuous, and often hilarious.

Perhaps no film better embodies this idea than the 2003 monstrosity-come-masterpiece The Room, most simply described as a romantic drama about a love triangle. The film’s writer, director, producer, and star, Tommy Wiseau, is notoriously secretive about his nationality (he’s likely of Eastern European stock), but he’s notoriously un-secretive about his affection for America. According to the book The Disaster Artist, the director imposed a five-minute moment of silence on the Room set after the 9/11 attacks, before going on an expletive-filled rant about Osama bin Laden and leading a chant of “USA! USA!” In explaining to his Room co-star Greg Sestero why he celebrated Thanksgiving Month instead of Thanksgiving Day (by eating turkey for all 30 days of November), Wiseau said, “We live in America. Anything is possible. I love living American life.”

It’s reasonable, then, to think that Wiseau’s love of all things America would also extend to the nuances of American conversation, including small talk. The Room features plenty of idle chatter, the dialogue a strange mix of stilted and casual, vanilla and crude. Take one memorable (and frequently quoted) exchange between Wiseau’s character, Johnny, and Sestero’s character, Mark, Johnny’s best friend:

Mark: How was work today?

Johnny: Oh, pretty good. We got a new client, and the bank will make a lot of money.

Mark: What client?

Johnny: I cannot tell you; it’s confidential.

Mark: Aw, come on. Why not?

Johnny: No, I can’t. Anyway, how’s your sex life?

Mark: I can’t talk about it.

Johnny: Why not? Oh god, I have to run.

Mark: Already?

Johnny: Yeah, I’m sorry.

The entire conversation takes place in under a minute, in the middle of the day, at a coffee shop. What’s more, shortly after ordering their drinks and sitting down at a table, Johnny abruptly leaves with no explanation. Where an American filmmaker might not think to include such an apparently pointless discussion (the scene adds nothing to the plot), Wiseau seems to think the scene lends everyday realism to the movie. The baffling dialogue is what fans tend to mock (Anyway, how’s your sex life?). But the exchange crucially understands the comforting ritualism of small talk between friends, as well as the utter dispensability of such moments—which makes the film endearing despite its flaws.

There are countless other awkward scenes like this that at first feel like unnecessary padding, but that serve to flesh out the portrait of a typically “American” man and his group of friends. At one point, Johnny goes into a flower shop to buy roses for his fiancee, Lisa, and has a rushed exchange with the owner that feels like a list of non-sequiturs (“Can I have a dozen red roses please?” “Oh, hi, Johnny. I didn’t know it was you. Here you go.” “That’s me!” … “You’re my favorite customer!”). The brief encounter is usually laughed off as nonsense, but it quietly reinforces the idea that trivial banter acts as a social glue—an idea that an American writer might take for granted or over-intellectualize, but that Wiseau, as a foreign filmmaker, presents quite plainly.

Sometimes in The Room, lighthearted small talk veers uncomfortably into serious subject matter, even if the easy tone persists. Like in the scene where Lisa’s mom, Claudette, shares some bad news: “I got the results of the test back. I definitely have breast cancer,” Claudette says, as though reporting that it’s definitely going to rain on Saturday. “Thanks for paying for my tuition,” Johnny’s college-aged ward, Denny, tells him offhandedly in another scene, as if graciously thanking a waiter for bringing a drink refill. Such lines brand themselves in the minds of viewers, in part because of how they violate the unspoken rules that govern polite conversation. Rather than humanizing the film’s characters as intended, they come off as dissonant and eerie. At times, in its quest for authenticity, The Room spectacularly misses the mark and falls right into the uncanny valley.

* * *

Birdemic: Shock and Terror, too, has some profound insight to share on chit-chat culture. The 2010 film, written and directed by James Nguyen, a Vietnamese filmmaker, blends romance and horror with a pro-environmentalist message to tell the story of a young couple in Silicon Valley who have to fight to survive after birds start murdering humans. The movie leans heavily on American Dream idealism, with its protagonist Rod going from software engineer to millionaire overnight after his company is acquired for “a billion dollars.” It also contains some of the most cringeworthy American-style small talk ever committed to celluloid, mostly taking place between Rod and his love interest, Nathalie. Like the following phone conversation:

Rod: Nathalie?

Nathalie: Who is this?

Rod: It’s Rod.

Nathalie: Oh, the guy from the restaurant! What’s up?

Rod: Hey, it was nice running into you at Half Moon Bay.

Nathalie: Yeah, it was nice meeting you.

Rod: So. How’s your day?

Nathalie: My day’s going well. How’s yours?

Rod: Great. I made a big sale today.

Nathalie: Good! Fantastic!

Rod: Thanks.

Nathalie: I, uh, closed a big job offer today with Victoria’s Secret.

Rod: Wow, congratulations. I think you’ll look great in those lingerie.

It’s precisely the kind of conversation Boomer railed against in his Modern Love column—“dull droning” that people see as a prerequisite for true intimacy. The same goes for a later scene when Nathalie and Rod are on a date at a Chinese restaurant, and she asks him what he does for fun. “Watch football,” he replies. “Especially the 49ers. Also part-time Eagles fan. And a little exercise. Tennis. How about you?” The same goes, yet again, for when Rod meets Nathalie’s mom for the first time. “I really like retirement,” she tells him pleasantly. “I like to travel. I like to cruise. And I enjoy watching television.”

On screen, these scenes are boring and repetitive—Ugh, who cares? is a common response. They also smack of unbelievability, at least to viewers used to seeing more artfully scripted interactions. But the truth is, most pop culture imbues informal chatter with far more dignity (and entertainment-value) than the average person is likely to experience in real life. Like Wiseau, Nguyen seems invested in conveying how all-American his characters are. Look how normal and relatable they are! he seems to be saying. And he’s right. On Mad Men, that pinnacle of TV writing, every scene is lousy with gems (like Hollis the elevator operator saying, “Every job has its ups and downs”). But Nguyen’s relative lack of pretense—awful as the cinematic result is—is what helped make Birdemic a classic in its own right.

* * *

Slightly less of an obvious fit into this pattern is the 1991 cult hit Samurai Cop. Written and directed by the late Iranian filmmaker Amir Shervan, the movie blends procedural and martial-arts genres, and stars Joe Marshall as a man trained to fight by “the masters in Japan,” brought to Los Angeles to help the police bring down a Japanese drug gang. The film expresses a preoccupation with American ideals (“This is America, land of freedom and law,” the gang leader declares at one point, while his lawyer threatens to sue the police for harassment), which suggests Shervan’s interest in broadly capturing cultural nuances.

Samurai Cop features much less aimless dialogue than The Room or Birdemic, but most of the film’s small talk feels like a vehicle for flirting or casual racism. “What’s an All-American girl like you doing with a geek like this?” Joe asks an attractive blonde sitting next to the Japanese gang leader in one scene. Later, he shows up at her office unannounced and after some empty chatter confesses, “Let’s just say I think you’re very pretty. Jeez, where are my manners. I haven’t even introduced myself.” Not much earlier in the film, Joe indulges some lighthearted sexual banter with a nurse who places her hand down his pants.

With such exchanges, the film seems to be innocently aiming for humor or romance, but ends up showing how small talk that relies solely on first impressions can be inappropriate or insensitive. After confronting the drug cartel at a restaurant, Joe and his partner Frank stop a flamboyant, heavily accented, Costa Rican waiter and try to get information out of him by indulging in a quick chat. He tells them his first name (“Alfonso Rafael Federico Sebastian”), but before he can say his last name, Joe gets annoyed and rushes Frank out. “Aw come on, man,” Joe tells Frank. “His last name would’ve made a book.” Polite conversation with strangers can, of course, be irritating, but Samurai Cop captures the uglier traits that can surface from forced interaction. The film captures the ways in which not everyone in America is deemed equally worthy of routine civility—in other words, pretty white women can generally expect more leeway than a gay Latino man.

It’s always odd discovering a level of depth in works that, quality-wise, don’t invite generous interpretation. The Room, Birdemic, and Samurai Cop aren’t so much exhaustive ethnographic studies of the average American as they inadvertent comedies of manners. Their ridiculousness might render our own habits that much more ridiculous (I think you’ll look great in those lingerie)—but, occasionally, they can make them seem more sympathetic.

Writers and movie fans have spent plenty of time unpacking all the ways “so bad they’re good” films endure, at least among a subset of cultural consumers, and one reason that continually crops up is: earnestness. It’s an especially apt reason when it comes to these B-movies: Their odd charm lies in how sincerely they try to depict a tradition held up as the apex of insincerity. Movies, TV, and literature have long excoriated and celebrated small talk as an American institution, but in the hands of a foreign filmmaker, such portrayals don’t feel mean-spirited or remotely self-aware. Ironically, Nguyen, Wiseau, and Shervan’s cultural remove brought them—and by extension their audiences—closer to reality. However distorted the mirror, or scornful the laughter, the image they reflected back felt nothing short of genuine.

Why Ethiopia Blocked Social Media

NEWS BRIEF National exams in Ethiopia began on Monday, but until they conclude on Wednesday, Ethiopians will remain without social media.

The East African nation has already postponed university entrance exams for 254,000 students since tests were leaked online back in May. But now, to prevent further cheating, the government has blocked social media sites like Facebook and Twitter until the exams are over.

The ban has been in place since Saturday because, according to the Daily Mail:

Government officials said the sites have been blocked for the first time ever to ensure an “orderly exam process” and prevent students from becoming “distracted.”

Getachew Reda, Ethiopia's communications minister, said: “It’s blocked. It’s a temporary measure until Wednesday. Social media have proven to be a distraction for students.”

But some Ethiopians have found ways of getting around the ban. One blogger, Daniel Berhane, created one of those tools, saying the government’s actions were “unconstitutional” and had “no legal basis or procedural defense to deny the freedom of expression and communication of millions of citizens.”

Banning social media to ensure smooth national exams is not limited to Ethiopia. In June, the Algerian government also blocked access to social media sites in an attempt at preventing cheating on baccalaureate exams. Students there were apparently posting exam papers online, leading to dozens of arrests.

Unrest Returns to Indian Kashmir

NEWS BRIEF At least 30 people are dead in Indian Kashmir after a weekend of violence prompted by the killing of a separatist militant leader by government troops.

Those killed in the violence include 29 civilians and a policeman whose vehicle, authorities say, was pushed Sunday by protesters into the Jhelum river, drowning him. (The BBC reports the driver lost control of the vehicle as he was trying to avoid stone-throwing protesters).

The Indian Express newspaper has more:

Even as the strict curfew is in place for the third consecutive day, there are reports of people defying the curfew and taking to streets at different places in central and south Kashmir. Kashmir valley erupted after the killing of Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Muzaffar Wani in an encounter on Friday evening.

While the government imposed curfew in all the major towns and villages of Kashmir, people took to streets in large numbers. The security forces fired bullets and pellets to disperse the protestors…

That action resulted in the civilian deaths, the newspaper added.

Wani, the young Hizbul Mujahideen commander, had become the face of the militancy in Jammu and Kashmir, predominantly Hindu India’s only Muslim-majority state. He was active on social media and, news reports say, his posts on Indian security forces’ actions in Kashmir drew a wide following.

Both India and Pakistan have claimed Kashmir in its entirety since their almost-simultaneous independence from Britain in 1947. India controls a little less than two-thirds of the region; Pakistan a little more than one-third, and China a small portion.

The northern Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir has three main parts: The Kashmir valley, which is predominantly Muslim; Jammu, where Hindus are in a majority; and Leh, where Buddhists and Hindus together form the largest population bloc. Consequently, most people in the valley favor union with Pakistan or independence while those in Jammu and Leh support union with India. The valley’s Hindus, many of whom have been forced out of their homes by separatist militants, also support staying with India.

Violence in the region has subsided since its peak in the early 2000s, but there have been periodic flare-ups, including the current unrest.

July 10, 2016

A Very Murray Wimbledon

NEWS BRIEF

Andy Murray of Great Britain claimed his second Wimbledon singles title Sunday, defeating Milos Raonic of Canada in straight sets.

Murray’s 6-4, 7-6, 7-6 victory comes three years after he became the first British man in 77 years to win the singles title at the same tournament. Raonic did make history: he is the first Canadian man to reach a singles final in the Grand Slam tournaments, the four most important annual professional tennis events——Wimbledon and the U.S., Australian, and French opens.

Murray gave his trophy plenty of kisses while on the court, as is tradition, and then brought it with him to his ice bath:

Holding this bad boy makes the ice bath that little bit more bearable

The Hundreds Arrested in Protests Over Police Shootings

NEWS BRIEF

Protests against police killings of black men led to road closures, clashes with police, and hundreds of arrests in cities across the United States on Saturday night.

About 100 demonstrators were arrested each in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and St. Paul, Minnesota, NBC News reported Sunday, the sites of two fatal shootings last week that have sparked widespread protests and renewed debate over racial disparities in American law-enforcement practices. DeRay McKesson, a prominent activist in the Black Lives Matter movement who ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Baltimore this year, was among those arrested in Baton Rouge.

It was the third straight day of widespread demonstrations after police shootings that occurred within a day of each other, and which were captured on video that was widely circulated online. On Tuesday, Alton Sterling, 37, was killed by police in Baton Rouge, where he was selling CDs in the parking lot of a food mart. Bystanders filmed his death on their cellphones. Sterling allegedly had a gun in his pocket, but it was not visible when an officer shot him. On Wednesday, Philando Castile, 32, was killed by police in Falcon Heights, a suburb of St. Paul, Minnesota, during a traffic stop for a broken taillight. Castile’s partner, Diamond Reynolds, streamed the aftermath of the shooting on her cellphone using Facebook. In the video, Reynolds said the officer shot Castile after Castile said he was carrying a gun and had a permit.

On Thursday, the first night of nationwide protests, a gunman opened fire on police officers at a demonstration in Dallas, killing five officers and wounding seven others. The gunman, identified as Micah Johnson, a 25-year-old Army veteran who served in Afghanistan, was killed by a remote-controlled robot bomb after an hours-long standoff with police. Officials said Johnson said he was upset by the shooting deaths in Louisiana and Minnesota and “wanted to kill white people, especially white officers.”

Protests took place Saturday night in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Nashville, and other cities. Dozens were arrested in New York and Chicago, CNN reported Sunday. In Baton Rouge, demonstrators chanted and carried signs that read “I can’t keep calm I have a black son” and “am I next?” In St. Paul, dozens of people marched along Interstate 94, a major highway, shutting it down to vehicle traffic. Some protesters threw rocks, bottles, and other objects at police, injuring at least three officers, Reuters reported Sunday. Photos from the scene show police officers using pepper spray against demonstrators. Around midnight, police deployed smoke bombs in an attempt to clear the demonstrators blocking the highway.

Burn It Down: How to Set a Fire and Why Makes Teenage Angst Literal

If fire is a metaphor for man’s primal nature, it can also describes a child’s innocence: Only kids stare directly at the sun, or try to touch a candle’s flame, because they don’t know any better. The narrator of Jesse Ball’s latest novel, How To Set A Fire And Why, is a young woman named Lucia for whom fire signifies both naiveté and power. She’s a high schooler who suddenly loses her parents, rendering her hapless and vengeful; she also has pyromaniacal tendencies. As Lucia confesses partway through the book: “When I think about what my future holds, it is a bit like looking into the sun. I flinch away, or I don’t and my eyes get burned down a bit, like candles, and then I can’t see for a while.”

In How To Set A Fire And Why, Ball is once again experimenting with bold characters. But in making Lucia an arsonist, he possibly extends the metaphor too far. Yes, Lucia has been burned, but her impulse to set fire to everything in response feels too literal, making her yet another destructive, impossibly precocious teenager in literature. Writers have long used young narrators—especially brilliant, angry, or misunderstood ones like Lucia—to offer surprising insights, and to comment on the flaws of the adult world. But How To Set A Fire And Why deliberately keeps Lucia at a distance from readers, and the result is that she sometimes feels more like a too-clever trope than a person.

Like some of Ball’s earlier and equally creative works (Silence Once Begun, The Way Through Doors), the novel is told in first person. This approach should make it easier for Lucia to establish a rapport with the audience, but she’s brusque from the opening pages: “I live with my aunt—dad = dead, mom in lunatic house.” As Ball explained in an interview with The Paris Review two years ago, “I think a book is often an account, or a series of accounts, that create a world that is sort of half of the world. There are references to a world, and then the reader supplies the other 50 percent.”

But Lucia’s abrupt tone makes it challenging for the reader to create a larger context for her behavior—or to supply “the other 50 percent.” Her father has died suddenly, though it isn’t clear why; her mother lives in a mental asylum There’s Helen, Lucia’s babysitter-turned-bartender, who makes Lucia cocktails after she has visited her mother, and then drives her underage drunken charge home. It seems that the one anchor in Lucia’s life—and ours, as readers—is her aunt, Lucy, whose relative maturity, stability, and humor help readers better understand the girl telling the story.

For most of the book, Lucy is the only adult who shows any kind of understanding and patience for Lucia. She, in turn, connects with her aunt’s loneliness and peculiar gardening habits:

The garden is poorly kept. The garden is full of dead things. The garden does not get as much sun as it should. When you are in the garden you can still occasionally hear noise from the street. The garden is inexpert. It appears abandoned.

In sum: the garden has excellent character, and it knows all the right people.

How To Set A Fire And Why opens with a “pretty ugly scene” in the principal’s office—the first of many—where Lucia is expelled for biting a student after he steals her lighter. When she does finally connect with a teacher at her next school, he recommends that she apply to an exclusive higher-education program. Not surprisingly, she delivers on the IQ test, the oral interview, and the essay. Because underneath all of Lucia’s rage is—of course—a smart, attentive young woman.

Young narrators like Lucia can be vehicles for powerful, honest stories—they can get away with holding innocent beliefs, or making hugely ambitious decisions. In Moby Dick, only Ishmael can discover the grand meaning of life while at sea. Only Proust the child can confess just how much he wanted his mother to kiss him goodnight. Only the Compson children can grieve over their family crises with such searing language in Faulkner’s The Sound And The Fury.

Many of Ball’s young characters in How To Set A Fire And Why possess this energy: Lucia’s rowdy classmates, the orderly who looks after her mother, the members of the arson club she joins three days after starting her new school. Lucia explains that “there are clubs forming all over the country … for people who want to set fires, for people who are fed up with wealth and property, and want to burn everything down.” Whether or not every high school is a gathering place for arsonists, Lucia quickly meets other students who are restless to destroy property and leave their mark—a universe of restless youth too smart for their own good.

At their best, young narrators reflect on aspects of the human experience—childhood, growing up, self-discovery—that analytically minded adults often overlook. Though Lucia has striking moments of clarity (like her aforementioned looking-into-the-sun line), these instances are distributed too widely across the nearly-300 page book to have a lasting impact. Readers learn about her love for reading through the titles she mentions—Barbarian in the Garden by Zbigniew Herbert, the French surrealists Antonin Artaud and Alfred Jarry, and Rumi’s poetry—but her name-dropping often feels like a juvenile attempt to signal an inquisitive mind. Like any teenager, Lucia is searching for answers. But she doesn’t like to ask questions; instead, she acts. She doesn’t ask what happened to her mother, even for her readers’ benefit; she simply visits her every week. She doesn’t talk about her father, instead she keeps him in her pocket, in the form of his old Zippo that she can light on command and bring to life.

Ball argues that building a story is a shared duty. But it’s an impossible task if the characters refuse to meet their readers halfway. Perhaps he wants readers to struggle to connect with an arsonist teenager, even if she is fictional, and even if she controls the narrative, but it doesn’t always make for gratifying reading. To Ball’s credit, Lucia at least subverts the angry young man trope by being female. But for all of the author’s earlier literary triumphs, keeping pace with Lucia is frustrating, especially when she seems to be laughing at readers’ attempts to do so. In her own snarky words, “I have no intention of entering the sweet land of fiction, wherever that is.”

July 9, 2016

Serena's Wimbledon Victory

NEWS BRIEF Serena Williams claimed a record-tying 22nd Grand Slam singles title on Saturday, vanquishing Angelique Kerber in the women’s singles final at Wimbledon and avenging a loss to her at the Australian Open earlier this year.

Williams' 7-6, 5-3 victory—her seventh singles title at tennis’s most prestigious contest—matched Steffi Graf’s Grand Slam record in the Open era. The New York Times has more:

Williams, 34, has insisted that “22 has never been my goal,” but despite reaching three Grand Slam finals in a row this year, she had not been able to reach it.

She had not won a major championship since last year’s Wimbledon, losing in the semifinals at the 2015 United States Open and the finals at the Australian and French Opens this year.

Margaret Court holds the overall record for Grand Slam titles, with 24 from 1960 to 1973.

Williams exulted in her historic victory on Instagram:

A photo posted by Serena Williams (@serenawilliams) on Jul 9, 2016 at 10:32am PDT

A few hours later, Williams and her sister Venus defeated Timea Babos and Yaroslava Shvedova to win the Wimbledon women’s doubles championship, taking their 14th Grand Slam doubles title.

A Black Police Chief on the Dallas Attacks

In the hours following the shooting death of five police officers in Dallas during an otherwise peaceful demonstration, opinions blared from social media, televisions, and newspaper front pages. In the din of it all, I reached out to the retired police chief Donald Grady II, who served as chief in Santa Fe, New Mexico, among other cities, and also trained police forces abroad in managing racial and ethnic strife among the ranks and with civilians. His 36 years on the force, as a black American, were marked by some familiar tensions and themes—racial targeting, police brutality, unwarranted hostility, lack of cooperation, and mutual paranoia. In a candid and expansive conversation, Grady unpacked for me some of the complexities of wearing a blue uniform while living in brown skin. An edited version of our conversation follows.

Juleyka Lantigua-Williams: What was your reaction?

Donald Grady II: Disappointment. Heartache. I’m disappointed that anyone would decide that the way to resolve issues that we have between the public and the police, in particular minorities and the police, is through additional violence. I don’t understand how anyone could rationally believe that perpetrating violence against the police would somehow endear the police to the rest of society. Heartache because we’ve got people dying all over this country. We’ve got civilians dying at the hands of the police and police dying at the hands of civilians. And rather than talk about things reasonably, logically, we have the police ratcheting up the rhetoric and we’ve got members of the community ratcheting up the rhetoric and that doesn’t resolve any issues at all. It bothers me any time we lose a citizen or we lose a police officer We have to recognize that police officers are citizens too.

Lantigua-Williams: What do we do now? How do we show that we value blue and black lives?

Grady: We have to get police administrators and police officers to recognize that just because they put on a blue uniform does not mean that they’ve divorced themselves from being citizens. They were citizens before they ever became police officers. They don’t lose that status just because they put a uniform on. For years, there’s been a line between the police and the public, and its perpetuated oftentimes by the police--that’s an unfortunate thing to say but it’s true. We perpetuate it by having an us versus them attitude.

Police officers begin to think that the only good people in the world are police officers, and that everybody else is somehow the enemy. I’m not saying every police officer does it, I’m not saying that everyone is guilty of it, but there’s a preponderance of people in the police profession that really do draw a line between the police and the public and they see themselves as an occupying army, as someone that has to be the champions for what they consider the good people.

Unfortunately, being the good people oftentimes translates into being a non-minority. Minorities are typically viewed as the dangerous classes, and they’re seen by too many police officers as symbolic assailants. Society has perpetuated that myth forever. We attribute things to minorities that don’t exist but we make ourselves believe that they do … Police officers buy into that. I’ve done policing for 36 years of my life, so it’s not as if I’m not anti-police. I’m very pro-police, but I’m pro democratic police. I’m not pro autocratic authoritarian police.

Lantigua-Williams: The same way there might be within the police culture a generalization that adds automatic criminality to certain populations, there are black and brown communities that say the police are not responsive to us, so some of our relationships with them are preempted by our not receiving adequate security or not having the same response times. In your experience, how has that played out? Is it a factor in the tension between police and communities.

Grady: Of course it’s a factor. But the problem here is that it’s true. Minorities are not making it up that police are not responsive to their communities, that police are overly aggressive when they’re dealing with minorities. That’s not an illusion on the part of minority communities. That’s real. As a police chief, I have been stopped numerous times by police officers claiming that there was some violation with my car until they realized that I’m just a law-abiding citizen. I don’t identify myself as a cop when I’m in those circumstances, I just let them do what they are going to do. And like so many other African Americans I just say “yes, sir,” “no, sir” and let it go at that. But after a while you get tired of being stopped for doing nothing. After a while, even as a police chief, you get really tired of being put upon. There’s a thing that we call freedom of movement which is really revered in this country--that we should have the right to move freely without impingement from the police simply because.

Lantigua-Williams: How would you handle the unfolding events if you were the Dallas police chief today, as a man in blue and as an African American man?

Grady: I have been in those circumstances. The first, and most important thing that I do, is I refuse to lie. I will not fabricate. I will not falsify information. I will not do anything that makes the circumstance any different than what it actually is. The second thing is I’m willing to accept absolute responsibility for what I do and what the people who work for me do. I have an obligation to ensure that it doesn’t happen or that it doesn’t happen again … If my people did something wrong, we’ll fit it.

At the same time, if my people have done something right, I will let them know why it was right and why they did it. We have been so insular as police that we have put people off. You go to a police department it’s like going into a gulag, we barricade ourselves off from the public. We have bullet-proof glass if you go up to even complain about a parking ticket. That’s unreasonable. That’s not the way a democracy should work. If we’re open and honest, if we do what we know to be right, and we’re truthful with the people you don’t have an us versus them attitude.

Lantigua-Williams: Chief Brown said that the police department is hurting, that the profession hurting, that they need to feel supported by the city of Dallas and the whole country. There’s a notion of a “war on cops” that’s entered the conversation while many maintain that certain ethnic populations have been historically unduly targeted. Where’s the line, if we’re trying to be honest and speak in realistic terms, where’s the line between those two conflicting ideas?

Grady: I don’t necessarily see them as conflicting ideas. I see them as a misunderstanding of what’s actually taking place. We have to recognize that the very nature of policing in a democratic society creates a dynamic tension. You have freedoms in a democracy, these rights, but with every right comes an obligation. What sometimes the police forget is that there’s an obligation that’s associated with those rights. If I have a right to demonstrate, you have an obligation to allow me to do so uninterrupted.

Lantigua-Williams: That appears to be what was what was happening last night before the shooting began.

Grady: I understand that, and I applaud them for the way they were handling that before the shooting took place. I applaud them. They were doing just fine and I saw that as an example of the police being responsive to its community. But, as I told you, the very nature of policing in a democratic society creates a dynamic tension, there are always people that will not like what they see, what they hear, they’re not going to want to respond favorably to any imposition of the law. In a democracy, we have to have a contract with the police. We’re going to allow you to enforce the laws on us. If I break the law, you have the authority to enforce the law against me.

One of the things that we do when we grant them that authority we also grant them the authority to use force. We have granted the police the authority to use force to control our society when it’s deemed necessary. Most of us accept that with no problem. There are going to be segments of the population that will never agree to that. When you abuse that authority on certain segments of the population you have to expect that there will be pushback. No one can argue honestly that we have police officers, generally speaking, treating people of color equally to those people that are not of color or that we treat people in the lower socioeconomic brackets equally to those in the middle, upper and affluent brackets.

Lantigua-Williams: Might there be a rationale that some people have adopted that leads them to see a systemic issue in access to the instruments of social and economic mobility, and because police officers mitigate between the law and the citizenry, they have become a target?

Grady: I sometimes get really disillusioned when people use the word ‘perception.’ If in fact something exists, if it’s real, and someone believes it to be real because they see all the indicators that it is in fact real then that’s not a perception, it’s reality … It hurts my heart to know that my son could walk out the door and not come back because he’s been shot by a police officer and the police officer shot him to death because he was scared. There are cops that will tell you I’m not scared of blacks, but I told you about the symbolic assailant. All of our lives it’s drummed into us subliminally that you need to fear people of color. It’s not an illusion, it’s real … If you recognize that this is built in--because that’s the nature of institutional racism--and that we react unconsciously to things that we have heard all of our lives.

Lantigua-Williams: You have a son, and you had ‘the conversation’ with him?

Grady: The conversation I had to have with my son is the same conversation most black and minority parents have to have with their children. You have to understand that you have to interact differently with people—not just police officers, but with non-minority people—than most people that you would interact with. What he sees his friends do, he can’t necessarily do. And sometimes it doesn’t work.

A clear example is what happened with Philandro Castile in Minnesota. You can comply, you can do everything they tell you to do, you can do everything you’re asked, and there’s no guarantee that you’ll still come out okay. I’ve had to have that conversation. And you need to understand that if you do the wrong things it will almost guarantee you a negative result. My son is no longer with me so it’s not as if I can tell you how that turned out in the long term.

Lantigua-Williams: What happened to your son?

Grady: My son died when he was 14 due to a suicide. He was with me 14 years and it was a very pleasant experience so I have to feel blessed that he was with me for that amount of time.

Lantigua-Williams: I’m sorry. How old was he when you had the conversation?

Grady: He was only about nine, ten.

Lantigua-Williams: What precipitated the conversation?

Grady: We were talking about some things and that just happened to come up in one of the discussions. I’d been a cop for a long time. I was a cop when we were talking, and I had to let him know that all cops aren’t like me. All cops don’t see policing the same way I do. So while he understands how he can interact with me and what he sees me do with other people, that’s one thing. But what he can expect from other police officers will not necessarily be the same thing, and he needed to be aware of that

Lantigua-Williams: What was his reaction?

Grady: Remember, for those ten years, he had grown up black, so he had experienced some things already that told him that things weren’t quite right, not everybody gets treated the same. People forget that the n-word is a very hurtful word, but children start to hear that very early. He was in kindergarten when he first heard that word used at him. When students would pick on him and call him the n-word, the teacher would tell him that he had to have a thicker skin. Why would we let people tell our children that? But that’s the kind of response he would get from his non-African American teachers, which most of them were.

He had grown up with that. And that’s part of how we ended up with the conversation, and him having to recognize that it’s different for us. We grow up differently. We have to live differently and expect things to be done differently. Sometimes it will be fair, not everybody gets treated unfairly, but sometimes you do. You just have to understand how to deal with that so that you come out okay.

Bagpipes: A Rock-and-Roll History

A few years back, when a friend asked me to play the bagpipes in a concert marking the 15th anniversary of Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, I was thrilled. In my experience, most people see bagpipe music as fitting for only two types of occasions: weddings and funerals. So it was heartening to be asked to use the instrument to help recreate that defining work of late-1990s hipster quintessence. But there was one problem. “Those aren’t my kind of bagpipes,” I told my friend. I tried to explain to him how the album features uilleann pipes, or Irish pipes, which look and sound very different from their more recognizable Scottish cousins, and also tune to a different key. But my friend waved my words aside. “We just need them for the noise,” he said.

With his casual remark, my friend inadvertently made a profound point about the instrument: The history of the bagpipes’ inclusion in rock music is, in many ways, a history of noise. Dozens of kinds of bagpipes exist throughout the world, but it’s the loud Scottish variety that are prominent in popular culture and that many associate with an iconic kind of racket. Scottish bagpipes are the noisiest unamplified instrument on earth: A single set of pipes produces between 95 and 110 decibels of sound, putting them closer to a jackhammer (95 decibels) than to a piano (60 to 70 decibels).

Unlike with other instruments, this volume range is static, making the noisiness of the Scottish bagpipes both very public and impossible to ignore. The bagpipes don’t simply request your attention—they hold it hostage, which is why they work for ceremonial events like weddings and funerals. It’s also why they’ve historically worked so well with rock music. AC/DC’s first big hit, “Long Way to the Top,” notably used bagpipes during the era of its frontman Bon Scott, whose birthday is still celebrated in Scotland every year (he would have turned 70 today). In addition to being spectacularly anarchic-sounding, bagpipes have long been part of a tradition of protest—one that’s perfectly in line with the disruptive ethos rock was founded on.

For decades, rock musicians have been using bagpipe noise to amplify political messages in their work. Sometimes, this artistic choice works on two levels: First, there’s the visceral impact of the instrument’s unique sound, and second, there’s the bagpipes’ more subversive history of being associated with protest. Take, for example, Eric Burdon and The Animals’ 1968 hit “Sky Pilot,” which includes a full 60 seconds of Scottish bagpipes. The single was released in January of 1968, during a time that also marked the launch of the Tet Offensive and the escalation of the Vietnam War. In order to include pipes on “Sky Pilot,” Burdon covertly recorded a practice session of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards pipe band—one of many groups that retains its links to British military units today. But the song the pipe band was playing was “All the Blue Bonnets Are Over the Border,” a tune linked with the Scottish Jacobite rebellion. The Jacobites were members of a Scottish rebel militia that rose against British forces in 1745, and historians commonly cite their resulting defeat as the end of the Scottish clan system and of traditional Gaelic culture in general.

The Animals’ inclusion of the pipes on “Sky Pilot” speaks to the way the instrument has been historically used to critique colonialist enterprises, in spite of its contemporary ties to those very enterprises. But so far as the use of bagpipes in rock music is concerned, “Sky Pilot” constitutes more of an exception than a rule. The song stands alone in permitting the bagpipes to function as an instrument, rather than simply as noise or backdrop. In “All Is One,” the final track on The Animals’ album The Twain Shall Meet, the bagpipes appear again, but this time as part of a discordant soundscape that also contains sitar (another instrument summoning histories of colonial oppression), electric bass, and drums.

For decades, rock musicians have been using bagpipe noise to amplify political messages in their work.

Most rock records, if they use bagpipes at all, tend to downplay the instrument. The result is that people hear chaos in these recordings without really recognizing the bagpipes. The Patti Smith Group’s 1978 album Easter is one such record. I listened to it for years before I even noticed the bagpipes, which appear amongst the din of the title track. The bagpipes in “Easter” sound a lot like the pipes in The Animals’ “All is One” and, for that matter, like the uilleann pipes in Neutral Milk Hotel’s “Holland, 1945.” In these songs, bagpipes form but one part of a many-layered cacophony, and so are downplayed to the point of inconspicuousness. Which prompts a question: Why include them at all?

Easter is probably best remembered as the album that finally got Patti Smith on the radio. Smith’s recording of “Because the Night,” which she co-wrote with her fellow New Jerseyan Bruce Springsteen, was a Top-20 hit. But the rest of Easter stays true to the kind of anti-authoritarian critique that has made Smith a central figure in punk rock. The bagpipes, which surface at the tail end of the very last track, cap off a record in which Smith rails against social sanction, proclaiming that “outside of society / that’s where I want to be.” And at the close of the title track “Easter,” the bagpipes sound a final, rebellious note against a wall of church bells and organ, symbols of institutionalized religion. The resulting dissonance is intentional on Smith’s part: The bagpipes can only play in one key, B-flat, whereas Smith’s “Easter” is in the key of C. That there’s a whole step of interval separation between Smith’s guitar and the bagpipes amounts to pure sacrilege in the eyes of music theory.

In this way, the bagpipes have earned a reputation for being impolite. The B-flat key setting means that they just don’t play nice with other instruments, and, with their range limited to only nine notes, that key setting is not negotiable. This is why AC/DC, on what is probably the most famous rock single featuring bagpipes, opts to meet the instrument on its own terms. 1975’s “Long Way to the Top” was written and recorded in the key of B-flat to accommodate Bon Scott’s bagpipe breakdown, which appears mid-song and features a kind of “call and response” between the pipes and the guitar.

Scott, being Scottish-born and Australian-bred, had grown up playing in Scottish pipe bands (though as a drummer), and his inexpert performance on the pipes forms the core of “Long Way to the Top.” In the bagpipe world, the lawnmower-like entrance of the bagpipes’ drones would mark the player as an amateur, but this song seems engineered to complement Scott’s vocals. After all, we’re talking about a track that celebrates the virtues of the hard-rock lifestyle in all its demented, self-destructive glory. To commemorate Scott, his hometown of Kirriemuir in Scotland erected a statue of him this year—grinning widely, with a set of bagpipes tucked under his left arm.

The bagpipes have earned a reputation for being impolite.

Renegade aesthetics also prove par for the course with Tom Waits, a singer who has staked his career on probing the boundaries of musical acceptability. Scottish bagpipes crop up halfway through Waits’ album Swordfishtrombones (1983), where they seem to ooze out of a sonic blackness and then to loop and overlap, the result of double-tracking. Here, as elsewhere in rock history, a bagpipe intro sets the tone for the song which, in the case of “Town with No Cheer,” is about a small Australian town that has run out of alcohol. Waits, though, has admitted his frustrations about working with the instrument. “It’s hard to play with a bagpipe player,” he explained in a 1983 interview with Rock Bill Magazine. “It’s like an exotic bird.”

It’s fitting that rock music has repeatedly embraced the “exotic” qualities of the bagpipes in spite of the practical difficulties involved. This pattern suggests a natural affinity between the instrument and the genre. “True” bagpipe music—or piobaireachd, as it’s called in Gaelic—also has a history of defying aesthetic norms in the service of political subversion. Piobaireachd music descends from an oral tradition and so doesn’t conform to standard musical time signatures or systems of notation. In this way, it pushes against the comparatively more modern, institutionalized reputation of the bagpipes, the one that includes military pageants and St. Patrick’s Day parades. The piobaireachd tradition fell into decline at the end of the 18th century following the Jacobite defeat but, recently, it has been enjoying a revival, as has Gaelic culture more generally. This leads one to wonder if Patti Smith and her ilk saw something in the bagpipes that even pipers themselves had, for years, been encouraged to forget.

“Listening to music,” observes the French theorist Jacques Attali, “is listening to all noise, realizing that its appropriation and control is a reflection of power, that it is essentially political.” The bagpipes speak the language of power in its many forms; that’s why even mainstream figures like Rod Stewart and Paul McCartney have found a use for them in their music. But the history of the instrument means that, with regards to rock, they are still most at home among the Patti Smiths and Tom Waits of the world—that is, among those branches of culture that seek to buck the status quo and give it a swift kick in the ear.

Atlantic Monthly Contributors's Blog

- Atlantic Monthly Contributors's profile

- 1 follower