Ethel Rohan's Blog, page 11

October 25, 2013

We Always Know Why, If We Listen Long Enough to Ourselves

I don’t know why I didn’t post this interview here that I did a few weeks back with the wonderful Brad Listi over at Other People’s Podcast. I feel so grateful to be included in this literali-studded, award-winning series, but I’ve been reluctant to share the interview beyond my writing community and with my personal communities. I also haven’t yet been able to bring myself to listen to the interview.

I think most of us find it difficult to listen to ourselves or to see our photos without the internal rush to criticize. I’m tried of criticizing myself. These days, I’m trying to talk to and about myself just as I would talk to and about my daughters–with nothing but love.

They say we can’t love others if we don’t love ourselves. Thus far in life, I haven’t found that to be entirely true.

There’s also a part of me still trying to hide myself, in particular my writing self, from certain people and communities. I’m still clinging to compartmentalizing myself. Here’s Ethel: Wife, Mom, School Parent, Irish woman, Immigrant, San Franciscan, Upright Citizen, Writer, Rebel, Struggler, The She’s So Together, The She’s Falling Apart. That’s something I’m also trying hard to work on these days: Here everyone, this is me, all of me. Like or leave, Amen.

It is with this at long last new meview that I give you my interview with Brad Listi. Like or leave, Amen: http://otherpeoplepod.com/archives/2394

October 19, 2013

In Its Jaws

Just last night I went to bed thinking, At least the grief has eased some. It’s six months since Mam died and almost three months since Dad died. The grief is less sharp now, less like it has me in its jaws. Yet this morning I’m hit with a fresh wave of pain and feel caught all over again between grief’s teeth.

I think of my parents every day, my Dad especially. Dad’s death is still shocking to me: How soon he died after Mam. How much more living he had to do. How horribly wrong his surgery went. How slowly and terribly he died over those six weeks.

I’m still asking empty rooms how is it better to allow someone starve and thirst to death over four weeks, as Dad did, than it is to give him or her a lethal injection? How is it humane to allow someone waste away over five years dependent on complete 24/7 care and emptied of everything except body, as my Alzheimeric mother did?

I return to Ireland in December to teach a writing workshop in Lismore Castle. It is hitting me now how hard the return will be. No Dad to answer the door to my Dublin home and hug me. No mother to visit, to stroke her hair and face and hold her warm hand. Dad’s beloved back garden gone–its maintenance too much for my sister and paving put in instead. Two roommates now living in our parents’ home with my sister, to help pay the mortgage and bills, so all sense of home gone. The first return to my parents’ grave since I helped my brothers and sisters lower Dad’s coffin in on top of Mam’s. To see both my parents’ names on the temporary cross.

Doing all that will be so much harder than it would have been to give permission, when all hope was gone, to inject both my parents with a lethal concoction and to let them go with dignity and in peace.

September 30, 2013

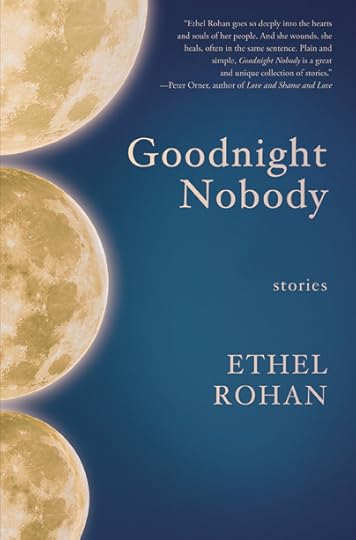

Official Publication of Goodnight Nobody Today

Today is the official publication date for Goodnight Nobody. I am deeply grateful to my wonderful publisher, Erin McKnight at Queen’s Ferry Press. Erin has proved a dream to work with and I couldn’t have asked for a better publication experience.

I remain deeply grateful also to Siobhan Fallon, Roxane Gay, Peter Orner, and Chad Simpson for their generous blurbs and spirits.

My thanks to Myfanwy Collins, Mary Miller, and Mya Spalter for reading the manuscript and providing excellent feedback.

Steven Seighman delivered a stunning book cover, with fancy French flaps, that I’m thrilled with.

From my heart, my thanks to the readers who have and will read Goodnight Nobody. I feel supported by so many and that’s a true blessing and source of joy.

It’s been a tough few months. I lost my mother, father, and father-in-law over a three month period. My deep thanks go to my parents-in-law for being such great grandparents and raising a great son, my husband. My deepest thanks go to my parents for doing your best, for bringing me here.

“I’ve learned that no matter what happens, or how bad it seems today, life does go on, and it will be better tomorrow. I’ve learned that you can tell a lot about a person by the way he/she handles these three things: a rainy day, lost luggage, and tangled Christmas tree lights. I’ve learned that regardless of your relationship with your parents, you’ll miss them when they’re gone from your life. I’ve learned that making a “living” is not the same thing as making a “life.” I’ve learned that life sometimes gives you a second chance. I’ve learned that you shouldn’t go through life with a catcher’s mitt on both hands; you need to be able to throw something back. I’ve learned that whenever I decide something with an open heart, I usually make the right decision. I’ve learned that even when I have pains, I don’t have to be one. I’ve learned that every day you should reach out and touch someone. People love a warm hug, or just a friendly pat on the back. I’ve learned that I still have a lot to learn. I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”― Maya Angelou

August 28, 2013

Dynamic Writing Workshop in Magnificent Lismore Castle–Registration Open

The class runs December 11-13th, 2013, from 10:30am to 4:30pm. This workshop is for writers of both fiction and creative non-fiction and is suitable for all levels. We will read at least one craft essay and deconstruct several compelling short-short narratives. Our goal is to hone the art of selectivity and write our best and briefest work. In-workshop writing will encourage fearless enjoyment of the process and the careful construction of the narratives we’re most burning to tell.

Participants will study and write amidst a fun and dynamic collective spark, and in a magnificent castle no less. Your time is now. Take the leap. Other writers teaching at the conference include: Robert Olen Butler; Karen Joy Fowler; Mariel Hemingway; Claire Keegan; Jane Smiley; Lily Tuck; and many more. Just think of all that creative genius gathered under one majestic and historic roof amidst one of the most beautiful landscapes on earth. Come. Join me in Lismore. We will do great things together.

Over the past decade, I’ve previously lectured and taught in private workshops and at Books Passage, Inc.; San Francisco Writers’ Grotto; and the Cork Int’l Short Story Festival. Going forward, I will also lecture on revision in the MFA program at San Francisco State University. To register for the “Brilliance of Brevity” workshop please email Nancy Gerbault at abroadwriters at yahoo.com. Workshop cost is $500 (approx. €379 Euros). In addition to accommodations in the Castle and in the town’s hotels and B&Bs, affordable housing in Lismore and its environs is also available and again email Nancy at abroadwriters at yahoo.com for details.

Lismore is an idyllic heritage town located in picturesque County Waterford. Lismore Castle and its spectacular gardens are situated in Blackwater Valley and overlook Blackwater River, rolling wooded hills, and the Knockmealdown Mountains. The gardens, laid out over eight acres within the Castle walls, are believed to be the oldest in Ireland and retain much of their original Jacobean form. Originally built in 1185 by King John, Lismore Castle was owned by Sir Walter Raleigh and later Richard Boyle, First Earl of Cork, before passing to the Fourth Duke of Devonshire in 1753. In recent years, the Castle has been lovingly and extensively upgraded by successive Dukes while retaining the Castle’s historic charm and beauty.

August 26, 2013

Winners Announced of Abroad Writers Conference Flash Fiction Contest

Heartfelt congratulations to the following winners of the Abroad Writers Conference Flash Fiction Contest. Robert Olen Butler, Pulitzer Prize Winner & F. Scott Fitzgerald Award for Outstanding Achievement in American Literature, selected the three winners:

1st Place: Darothy Durkac — “What He Did with the insides”

2nd Place: Kelly Creighton — “Until They’ve Hatched”

3rd Place: Hugh McQuillan — “Music To Drive By”

1st Prize: Free Admission to my 3 Day “Brilliance of Brevity” Workshop. Single room for seven nights, conference & a celebratory dinner in the castle with Judge, Robert Olen Butler. Total value $1, 085.

2nd Prize: A scrumptious full banquet dinner at Lismore Castle with conference luminaries: Robert Olen Butler, Karen Joy Fowler, Sarah Gristwood, Mariel Hemingway, Edward Humes, Claire Keegan, Jacquelyn Mitchard, Anne Perry, Michelle Roberts, Alex Shoumatoff, Patricia Smith, Jane Smiley, and Lily Tuck. And, yeah, I’ll be there too.

3rd Prize: A complimentary pass to conference events at Lismore Castle.

The three winning stories will be published in 2014 in Ireland’s premier literary magazine, The Stinging Fly.

Shortlist:

Soojin Kim — “You Sound Well”

Ellen McCarthy — “In The Rain”

Darothy, Kelly, Hugh, Soojin, and Ellen–I very much look forward to meeting at least some, if not all, of you in Lismore Castle in December and to congratulating each of you in person. My deep thanks to everyone who entered the contest.

From Robert Olen Butler:

I was truly impressed with the high quality of submissions in this contest. The decision process was arduous and nuanced. The top twenty or so would have been among the winners of more than a few flash fictions contests I’ve judged. And I saw real potential in virtually all of them. Ireland must have been a powerful lure for nascent talent. That I might have a chance to work with some of these writers is very exciting for me as a teacher.

And please send all the submitters my warmest regards. There’s not a one of them I wouldn’t be sincerely delighted to work with. Honestly, given my years of experience judging contests, that surprises the hell out of me.

I still can’t quite believe my good fortune to return to Ireland in December to teach a writing workshop in Lismore Castle on short-short stories and the brilliance of brevity. I will teach a three day course December 11-13 from 10:30 am to 4:30 pm.

The course will be packed with reading, writing, and workshopping, and all infused with enthusiasm and passion. To register email Nancy Gerbault at abroadwriters at yahoo.com. Workshop cost is $500 (approx. €379 Euros). Affordable housing in Lismore and its environs are available and again email Nancy at abroadwriters at yahoo.com for details.

Please join me in Lismore. We will do great things together.

August 20, 2013

The Places He Brought Us

After the nurses removed Dad’s life support and feeding tube, he was transferred from the ICU to a small single room in AB Cleary ward, allowing us privacy and 24/7 access. Think ABC I told my brothers and sisters, on the fourth floor. While staff transferred Dad, I walked outside, exhausted and melting in the record Irish temperatures but glad of the fresh air and the reminder there was world beyond the hospital. Inside the dim and cool cover of the pub, I inspected the corridor of carvery and ordered the grilled salmon with roast and mash potatoes and a mound of cabbage and also julienne carrots and turnips heaped like fingers. I paid with my credit card, thinking how this trip was costing me thousands. Seated at a table next to a window and away from everybody else, I ate the entire meal, all those colors, even though the vegetables tasted burnt. I drank a glass of cold, tart white wine. After, I sat out back of the pub and ate a large whipped ice cream cone with a fat stick of chocolate pushed through, all while listening to the water fountain make its music. I’d read once that people lose weight with grief, without fail.

Dad worked as a barman in Dublin for over fifty years. Mam said to never marry a barman, they are never home. Throughout most of my childhood, Dad’s two days off work each week were Tuesdays and Fridays. Fridays, he cooked fish and chips for dinner. He peeled and handcut the potatoes, then placed the salted chunks into the fryer of rolling fat. The secret to his delicious chips, he maintained, was lifting the almost fried potatoes from the fat and letting them breathe for a few seconds before returning them to the fryer for another minute to bring them to golden. The eight pieces of cod, he’d coat those in flour and salt and ease the school onto the frying pan, into inches of melted butter. Tuesdays, Dad cooked burgers and chips. He fed the sirloin steaks into this large silver mincing machine that took center-stage in the kitchen while he prepped. As he turned the handle, came ribbons of meat. That mincer was to him what a Rolls Royce would be to most. “This way you know exactly what you’re eating.” Dad had a paranoia about food hygiene, about being conned. During the recent horse meat scandal in Europe and in America, Dad said down the phone to me, “Didn’t I always say.” Dad added salt, pepper, and chopped onions from his garden to the eight burgers and sealed the lot with egg and a fine dusting of flour before placing the rounds of meat inside the frying pan and its bubbling butter. That salad, too, that he made from his garden–the scallions, butter lettuce, boiled beets, sweet tomatoes, and hard-boiled eggs–all mixed with Hellmann’s Salad Cream. Sometimes, Dad also made us goulash, a spicy Hungarian beef stew I actually liked. I liked even more that no one else I knew had ever heard of goulash, let alone how to cook it well.

I finished my ice cream cone, feeling too full and a little sick. Just as I was about to leave the pub and return to Dad, a plane roared overhead, drowning out the fountain. When we were kids, Dad drove us the few miles from our house and to the road behind Dublin airport, to eat ice cream and watch the planes land and takeoff. I remember feeling very small and worrying the planes would make me deaf, would drop on us. Other times, Dad often drove us to Donabate beach where we’d enjoy more ice cream, and also sandwiches and warm red lemonade. Dad had a dread of sand in his food, taught us to hold our sandwiches up high and never to eat on the beach when there’s a breeze. Unable to swim, Dad would crouch inside the ocean with bent knees and straight back and teach us how to pretend the breaststroke. Regular trips also to his home county of Wicklow and his beloved village of Lacken where he grew up, and where many years later my husband and I would obtain special permission to marry in its by then disused church–cause I was always pulling stunts to show Dad how much I loved him. “Look, Dad, see me. I love you.” Throughout our childhood, Dad drove us city kids to lots of remote and tiny country churches and to holy wells and shrines. We’d light candles and say prayers and buy holy water and watch the sun set the stained glass windows alive.

When I returned to the hospital, I found Dad alone inside Room 3 of AB Cleary ward. The stink from his bowel bag stopped me still. I pushed myself deeper into the room, seeing Dad had an oxygen monitor clipped hard to his first finger, but not attached to any machine, and a blood pressure cuff wrapped around his arm tight. His urine bag looked about to explode. I removed the cuff and finger clip, made more furious by the red marks on Dad’s puckered skin and the beginnings of a purple bruise below his fingernail. I stood in the corridor with evil eyes, searching out an available nurse amidst so many patients, visitors, and staff. I waited to get someone’s attention, a sense of panic rising. Trapped I felt inside the back and forth swell of rushing and shuffling, of wheelchairs, stretchers, medicine carts, food trolleys, and portable stands attached by tubes to the sick. The tall, thin, young nurse said she was sorry, there was nothing to be done about the stink. An electric fan, I demanded, and more air fresheners. I didn’t mention the cuff, finger clip, or brown-yellow urine bag about to go off like a bomb. Too coward.

The stink and record summer temperatures shrunk Dad’s room, made its air thick, choking. The hospital windows wouldn’t open beyond a few inches. So people can’t jump. I rubbed lavender lotion into my palms and held my hand to Dad’s nose, told him to smell the flowers. Told him about the white orchid I’d brought him. Dizzy, feeling I might vomit everything from the pub, I told him I was sorry it had come to this. The nurse appeared with the electric fan and I asked if I could please remove the anti-clot stockings that bound Dad’s feet and calves. I didn’t tell her that my last trip home, less than three months earlier and just days after Mam had died, I’d thrown out a little hill of Dad’s socks. Socks with jagged tears in the cuffs. Dad, dismayed, explained that he liked his socks split at the tops, cut with scissors so the cuffs wouldn’t cling to his legs. I should have known, I realized. Dad had always cut off the sleeves of his shirts and cardigans, wanting his arms out. Always drove with his driver’s window cracked open. Always paced the floors of the house at night before bed, enough times to cross the city and back, enough times to rid himself of his restlessness. These were the things my brothers and sisters and I thought of when we decided to turn off Dad’s life support. We could have let him live, but he was paralyzed from the chest down, had suffered several small brain strokes, had a bowel that couldn’t be turned off, and he would never ever leave the hospital care system. That, that would be like dropping Dad inside an enormous sock and cinching its cuff above his head.

August 17, 2013

Crazies

Dad’s married, middle-aged neighbors two doors up are deaf and dumb and they beat on one another. The beaters have two teenage daughters, aged maybe 14 and 18. In the past almost two decades, during my annual visits to Ireland, I’ve overheard what I’m told are just a few of the couple’s constant fights: Rage rising like fire from their house or from their car parked in the driveway–thuds, door slams, guttural screams, and amputated curses out of mostly the man, “fu…fu…fu…fu…fu”–, and always the high-pitched sounds building from both him and her like music made for torture, like the noise of two dogs on the ground tied to ropes getting dragged.

Almost two decades, and I’ve only ever seen the deaf and dumb mother going to and from her car or working clothes on and off the drying line or moving across her front windows like she’s inside a film screen. Until Mam died. When Mam died, just as the undertakers were about to take her coffin from the house and out to the flower-bright hearse, the deaf and dumb mother appeared at the bottom of our front path and, her hand rubbing large circles on her chest, grunted sorry. My sister and I thanked her. “Da?” she managed. No, I smiled small, smug. Dad was fit, healthy. Dad had years left in him. Dad wasn’t going anywhere for ages. Ages would in fact turn out to be three months. Our mother, I said. She’d likely forgotten our Alzheimeric mother in the nursing home for eight years, likely thought Mam had died long ago. And so Mam had in all but body.

Often over the years, though, I saw the deaf and dumb father. Saw him going to and from his work at whatever wherever in his car, saw him jogging and sweating on the street, saw him walking the black-and-white family dog, a dog with an eye tic. Felt such rage and loathing for the deaf and dumb father. Wanted to hit him. To beat him into stop. Always, I snubbed him.

The beaters’ oldest daughter now has a live-in boyfriend. She also has her parents’ rage. One evening, after a long day at the hospital, hours of leaning in to Dad as he lay dying and stroking his head, feeling his heartbeat through his scalp, I sat on Dad’s front stone wall, my bare feet pushing into his scorched grass, my face tipped to the sun that belongs to us all. The oldest daughter and her live-in boyfriend charged from the house, her shouting at him. They sat into the car in the driveway, blared the radio, shouted some more. Next the daughter ran at her front door, kicked at it until it opened. Minutes later, the live-in boyfriend turned-off the car radio blare and followed the oldest daughter into the house. More shouts, thuds, door slams.

Another day, the youngest daughter sent up screams and wails from the house like she was trapped in a fire. I said to my sister, how do you and Dad stand it? She said, crazies.

The evening I saw the deaf and dumb couple rough each other up and down their back garden, I wanted to shout at them, “Aren’t you tired? Don’t you just want it over with?” Instead I phoned the police on my cell while still watching. Their fight made me shake. Made me a girl again. Brought me back to Mam and Dad fighting, their words the fire that would burn down our house. Dropped me inside the flames that were my Dublin ex and me. The beaters made me feel I was on the motorway in heavy traffic, about to be smashed. The policeman said he’d send a car around. No car came. I phoned again. Another promise. Another no show. My sister said, that’s the way.

That night I lay in bed imagining myself screaming, imagining no one coming. Then I saw myself at the beaters’ front door, facing the five of father, mother, daughter, boyfriend, and youngest daughter, even the dog is lying there at their feet, like they’re all posing for a picture, and I lift my right hand, the hand thumping with the memory of Dad’s heartbeat, and I rub large circles on my chest.

August 16, 2013

Intensive Care Unit

Dad’s surgeon, a vascular professor, is also a singer-songwriter. Jaysus, don’t tell me that, Dad had said, he’ll be thinking more about his singing than me on the table. I pictured the singer-songwriter surgeon with a knife and fork aimed at Dad, a white napkin stuck in the collar of his blue scrubs, a large tissue diamond on his chest.

In the hours following Dad’s surgery, a surgery to address an about-to-burst abdominal aortic aneurism (a “bulge” to quote the no-nonesense man who gave me life), Dad suffered massive internal bleeding. His singer-songwriter surgeon stayed through the night working on him. My baby brother phoned from the Dublin ICU to the redwoods of Yosemite, told me get on a plane quick. Said they’d begged the singer-songerwriter surgeon, told him our mother had died just two months earlier, to the day.

The first time I met Dad’s singer-songwriter surgeon, I wanted to like him, to thank him. He’d stayed through the night. Had operated on Dad four times in 18 hours. Was the reason Dad was now on life support and not in the hospital morgue. Doctor also bore acne scars, hollows in his face that reminded me of my awful hide-my-head years of pimples, creams, scrubs, antibiotics, yeast infections, and squeezing and bursting and scars and pores still with too much hole. Reminded me of the deeper, worser, widespread pink-red hollows on Dad’s arms and back, scarred from when he was so horribly scalded as a boy.

Wanted to like the singer-songwriter surgeon because when the male nurse took the last remaining seat in the ICU waiting room, leaving his female colleague standing, the surgeon asked that male nurse to get up and let the lady sit. But something stopped me from liking the singer-songwriter surgeon. He was playing a part. Talking through his scalpel. Strumming his ego. He said Dad was trapped in a minefield, said he missed some mines just to hit others. Said maybe more mines will explode. Or not. Said his heart, his lungs, his kidneys. Said we owed a lot to machines and the ICU nurses. To 46 units of blood. Said Dad had a long, long road ahead. Said disastrous with the emphasis on ass. Said he didn’t come to work every day to do disastrous.

Watched, cringing, the singer-songwriter surgeon on YouTube. Next time we met, I disliked him more. Believed he’d botched Dad’s surgery just like he’d botched his songs. Singer-songwriter surgeon said Dad had improved, his heart, his lungs, his kidneys. Said there was hope. Said maybe there was something with Dad’s brain function, maybe something with his legs not moving. Said every day Dad stayed in ICU was a day too long. Third time we met the singer-songwriter surgeon we learned Dad was paralyzed from the chest down, had suffered several small brain strokes, had a bowel that couldn’t be turned off. I said, says I, if we had known all the damage we wouldn’t have spent 21 days in the ICU telling Dad to fight, telling him he was coming home. Why, said I, the diagnosis so late. Thought, thought I, singer-songwriter surgeon sing me that.

The fourth and final meeting with the singer-songwriter surgeon, after he’d supported our family’s hard-won decision to turn off Dad’s life support and remove his feeding tube, he said he was surprised to see me still there: Didn’t I live in San Francisco? Wasn’t I married with children? Didn’t I have a life and work and income I needed to get back to? I said I had. Said, regardless, I’d stay the course. He looked at me for several beats. Inside the left lens of his glasses, reflected a tiny rainbow. Then my Dad’s sister sitting amongst us in the borrowed hospital wheelchair, his last surviving sibling of six, my senile aunt, her unwashed odor, the repeated phrase, “I’m 85. He’s 78. He was the baby. He can’t go yet.” The singer-songwriter surgeon held her hand, spoke kind, told her in his experience women are stronger than men. Said, “You know your brother is very, very low.”

I watched singer-songwriter surgeon walk away for the last time. Thought so he’s an actor. We’re all actors. Thought so he could play worse roles. Could chase worse dreams. Thought so aren’t we all just watching for mines. Thought singer-songwriter surgeon good luck out there.

Singing

It would be wrong not to tell you how much I laughed with my brothers and sisters in the six weeks while Dad lay dying, in the week while he lay dead. How much we sang together. Laughed and sang together in a way we hadn’t since we were kids, and maybe not even back then so hard and long. Sang Dad’s favorite songs, the ones we’d played for him in the hospital, our phones on the pillow next to his head, at other times an iPod on top of his bedside locker. We sang every song we knew. I’m a rotten singer, even mime “Happy Birthday” in groups. But I sang for those seven weeks in Dublin. Because of the whiskey. Because I didn’t care. Because I did care.

I thought of the ballads my Dublin ex sang. Thought of how he’d attended Mam’s funeral services three months earlier. Thought how that was the first time I’d seen him, talked to him, in years. Thought back two decades and how crazy-hard I’d loved him. Thought how terrible-great we used to be together. Thought how I hoped he’d attend Dad’s funeral services as well. Thought of him holding me. Thought all this next to Dad’s dying bed. Thought God and my Dad and my husband to please forgive me. Thought how grief makes us crazy, makes you yearn.

We waked Dad at home for two days and a night, him so thin and shrunken inside the coffin, almost unrecognizable until we realized if we sat on the couch where we could only see him in profile, see just his face beyond his ear and not those sunken cheeks and those bones pushing, then he looked like Dad. The white lining of his coffin trimmed with glittery gold that I hated, loose white threads that I wanted to scissor, speckles of gold on the new black suit we’d bought Dad for Mam’s funeral that I scratched off with my trigger nail.

Family and mourners wanted me to put Dad’s glasses on him. “Ned always wore his glasses.” I resisted. It’s not Dad, I wanted to tell them. Dad always wore his glasses. This isn’t Dad. But upstairs I went and back down again and placed Dad’s glasses on his face. Glasses on with eyes closed. The thin eyelids instantly discolored. Made him look like he’d two green holes in his head. Before the undertaker closed the coffin, I removed Dad’s glasses. I have them still. All the better to see you, my dear.

So few pieces of Dad to give. His cap to my sister. His huge potted hydrangea to another sister. His wedding ring and good shoes to our baby brother, Dad’s mirror-image in so many ways. The Wicklow jersey and his watch to the oldest. His gardening tools to the third brother. Me, I got his glasses and his gold house key. Key. Lock. Turn. Open. Mam. Dad. Home. I would fight with lions to keep that key.

I sang Amazing Grace to Dad in his open coffin. Sang with my brothers and sisters and the rest of our family and the mourners, my gifted young red-haired nephew the strongest voice in the throng, mine the weakest. Sang while looking at Dad’s face for the last time. Sang as I wondered if he could see us, hear us. Rise it, we Irish tell our singers. Rise it, I like to think Dad told us.

August 15, 2013

Never Seen the Like

My three brothers, two sisters, and I carried our mother’s coffin into the church on a Monday last April and out to the flower-filled hearse on the Tuesday. We carried her on our shoulders, raised her up. People said they’d never seen the like, women carrying a coffin. Dad, he said, it made him proud. I imagined his chest swelling, enough air to blow out all the church candles.

Three months later, of a Tuesday, I also wanted my three brothers, two sisters, and I to carry Dad’s coffin into the church and out again on the Wednesday. No breath left in him then to swell his chest, to quench light. But, yea, I wanted. Our brothers and husbands said we couldn’t. Too weak. Too emotional. Dad too heavy, his coffin too big. I said, too, by God.

My sisters and I, we tested our strength. On the Tuesday, with our brothers, we carried Dad’s coffin from his house and out to the shiny hearse. Inside voice said fool, said we’d drop him, said coffin crack asunder, said he’d roll and break, said serve you right for wanting spectacle. Serve. You. Right.

We carried. From the house to the hearse. From the hearse across the church yard up the stone steps and along the aisle to the altar. Heavy. Heavy nothing like my mother. Heavy hard to breathe. Heavy hard to keep my eyes open. Heavy hard to stay standing. To keep walking.

After, a red line marked my shoulder, that summit right at the meeting of the neck. Later that night, pain and tenderness, and in the days that followed bruising.

The next morning, on the Wednesday, to take Dad out of the church and into the hearse and to the cemetery and into the grave on top of our mother, I carried Dad on my left shoulder, marking it too with a hot line, with tenderness, with a bruise that never ripened beyond red. I thought, too, by God.

Gone. The coffin. The flowers. The mourners. The hole in the ground. Both bruised shoulders. Gone.

Heavy. Heavy stayed.