Fredric H. Jones's Blog, page 2

May 8, 2013

GOING TO THE BOARD

When trying to come up with cheap and easy ways of learning by doing, it can be useful to learn from those who have gone before. I grew up with the most time-honored (or vilified) version of Say, See, Do Teaching.

My classroom had three walls of slate chalkboards. Throughout my grade school years, I did almost all my lessons — vocabulary, arithmetic, sentence structure, verb tense — at the board.

Working at the board provided the involvement and precision of one-on-one coaching. In addition, that format prevented a lot of squirrelly behavior because it enabled us to get out of our seats, stretch our legs, and do something.

A half-dozen times a day, I’d hear the teacher announce the beginning of a lesson by saying, “All right class, let’s all go to the board.”

Imagine the lesson was math. She would write a problem on the board, and we would copy it. Then she would say, “Class, let’s do this first problem nice and slow so we all get it.”

The teacher would explain and model step one, and then we would do step one. It was easy for her to monitor our work from the front of the class because it was written large in chalk.

Corrective feedback was given immediately, often by way of partner pairs standing next to each other. “Robert, would you check your partners multiplication on that last step?”

The teacher coached the class through the new skill just as a basketball coach might coach a team through a new play. With continual monitoring and corrective feedback, there was little worry about getting it wrong. Board work was relaxed. And, since kids enjoy writing on the board with chalk, it didn’t seem much like work.

After completing the first problem, we would erase it and do another problem. The process would be the same, but we would pick up the pace, because we now were familiar with the steps. Then we would erase and do another problem, then another. By that time, we were in the groove. Then the teacher would say, “Let’s do one last problem for speed, and then we’ll take our seats.”

Once we were at our seats, the teacher might say,

“All right class, would you please open your math books to page 67 and look at the practice set at the top of the page. Do you see anything familiar?”

There would be a few giggles, as we realized once again that we had done problems 1-5 at the board. Then the teacher would say, “I think you know how to do these by now. Let’s do problems 6-9 just for practice, and I will come around to check your work. When you have done all the problems correctly, I will excuse you to work on your science project.”

Doing lessons at the chalkboard had some real advantages for the teacher, as well as for the students. It was simple and cheap and never got old. And we were busy doing throughout the lesson — which kept us focused.

for more information about Say, See, Do Teaching, please visit http://www.fredjones.com

April 30, 2013

In One Ear, Out the Other

Have you ever been introduced to someone only to have that person’s name slip your mind before the end of the conversation? Welcome to your brain. That’s how it works. We have very little long-term memory in the auditory modality.

Now let’s apply that simple reality to education. What’s the primary modality used for instruction in every subject area at every grade level? Whoops! We have a problem.

At the secondary level, we have lectures. But even in third grade, teacher presentations often run ten minutes or more. Too much talking. Too much sitting. Not enough doing.

LEARNING BY DOING

Step one: Reduce the amount of stuff you give kids before asking them to do something with it.

Step two: Have the kids do something with it immediately before they have time to forget.

Successful instruction has a lot to do with packaging. There are only two ways to package student activity during a lesson. The first is the one we grew up with:

Input, Input, Input, Input Output

The second is the one that characterizes learning by doing.

Input, Output, Input, Output, Input, Output

Learning by doing focuses on performance. The teaching of performance is usually referred to as coaching.

You explain what to do next. You model what to do next. Then you have the student(s) do that step while you watch like a hawk. If there is error, you fix it immediately before it becomes a bad habit. You might repeat that step a few times to iron out the kinks. Then, when you are satisfied with performance, you proceed to the next step.

If lessons are packaged in that fashion, problems of cognitive overload and forgetting are nearly eliminated, while student engagement is maximized. In addition, assessment is continuous, not something that’s separated from performance and delayed until its relevance is lost.

for more information, please visit www.fredjones.com

April 23, 2013

Incentives vs Bribery

Motivation is managed through the use of incentives. Incentives answer the question, “Why should I?” By managing incentives, we can increase the motivation of students to work hard while working conscientiously.

But incentives must be used correctly, or they can create more problems than they solve. They must be used in conjunction with checking work as it is being done and providing immediate feedback. Otherwise, incentives drive students to work fast and sloppy.

It is, therefore, time for us to learn more about the technology of incentive management. To use incentives effectively, you must have fun. The principle that ties incentives and motivation together is, “No joy, no work.”

Most incentive systems in life are informal. The universal incentive in child rearing and family life is love. Love is both a bond and a motivator. Children who love their parents will often do things to please their parents.

For example, if you ask your twelve-year-old to carry the groceries in from the car, and he or she says, “Okay,” realize that your child has just given you a gift. But that gift is based on solid experience. You have just received a small dividend check from all the love and good times you’ve put into the bank over the years.

Some incentive systems in life are formal. They represent an agreed upon exchange of goods and services. Your paycheck is such an incentive.

But around the house, most of the formal incentive systems that we use as parents are embedded in routines to get the kids to do things that need to be done. The one I remember most clearly from my childhood was “the bedtime routine.” My mother would say, “All right kids, it is 8:30 — time to get ready for bed. Time to wash your face, brush your teeth, and get your pajamas on. As soon as you are in bed, it will be story time. But, lights out at 9:00.”

As you can see, the terms of the arrangement were no mystery. The faster we moved, the more time we had for snuggles and stories. Formal incentives and informal incentives work together. No matter what the formal incentive, we always try harder for someone we love.

Due to the overuse of formal incentives in classrooms during the past several decades, educators have become understandably concerned about “bribery.” We have become wary of the overuse of points, tokens, treats, and meaningless rewards. Many teachers have overgeneralized, however, to the point where they consider all incentives to be bribes. In order to avoid throwing the baby out with the bath water, we need to examine the appropriate and inappropriate use of formal incentives. Within this context, it is helpful to categorize formal incentives as either proactive or reactive.

A proactive incentive system is an exchange that is established in advance. These exchanges are typically innocuous, every-day events. Effective parents and teachers have always been instinctive incentive managers. They have a knack for pairing treats with chores in order to get work done. Here are some time-honored examples:

You have to finish your homework before you can watch TV.

You have to practice your piano before you can go out and play.

A reactive incentive system, on the other hand, is an exchange that is established in the heat of the moment. Imagine a situation in which your child will not cooperate with you. From his or her perspective, there is no good reason to do so. In frustration, you react to the dilemma by offering the child a reward if he or she will do as you want. This reactive incentive is a bribe. Take, for example, the following argument:

Mother: “Billy, I want you to clean your room.”

Billy: “I don’t want to.”

Mother: “Now, I want that room cleaned. It is a mess!”

Billy: “I want to go outside and play!”

Mother: “Not until you get this room cleaned!”

Billy: “I’m not doing it!”

Mother: “Oh, yes you are!”

Billy: “You can’t make me!”

Mother: “Listen, I’ll give you fifty cents when this room is clean, and then you can go outside and play.”

Unfortunately, when you use incentives incorrectly, they blow up in your face and give you the opposite of what you want. In this example the mother has just reinforced Billy for noncooperation, rather than for cooperation. By digging in his heels and saying “No,” Billy has been rewarded with fifty cents. If he had simply cleaned his room without an argument, he wouldn’t have gotten a penny. What do you suppose will be going through Billy’s mind the next time his mother asks him to do some chore around the house?

To put it simply, bribery is the definition of malpractice in incentive management. Nobody who is well trained in the technology of incentive management would even consider offering an incentive in that fashion.

In the classroom teachers need both informal and formal incentives to motivate students. Students naturally will work harder for teachers they like. But, formal incentives will play a more prominent role in the classroom than they do in family life.

For one thing, the students don’t know you, much less love you, on the first day of school. And, for another thing, some students resent you just because you are an adult authority figure. For those reasons, any teacher will need to develop technical proficiency in the design and implementation of formal incentive systems.

Simple classroom incentive systems are straightforward applications of Grandma’s Rule, which says: You have to finish your dinner before you get your dessert.

A simple incentive system is the juxtaposition of two activities:

A simple incentive system is the juxtaposition of two activities:

the thing I have to do; and

the thing I want to do.

The first activity is the task. The second activity is the preferred activity. The heart of an incentive system is the preferred activity. It answers the question, “Why should I?” It gives the student something to work for and look forward to in the not-too-distant future.

The simplest and most common way to schedule preferred activities is on a lesson-by-lesson basis. Grandma’s Rule implies the juxtaposition of two activities, one that you have to do (the task) and one that you would rather do (the preferred activity). Those two activities are typically scheduled back-to-back. When you finish the first activity (correctly, of course), you can work on the second activity until the period is over. Sometimes, however, that arrangement leaves the teacher and the students feeling as though the day is too chopped up, with never enough time to really get into the preferred activity. In such situations, the teacher might want to consider a work contract.

A work contract is simply a preferred activity that follows the completion of a series of tasks. Teachers in self-contained classrooms might leave the end of the day open for preferred activity time after all the day’s assignments have been completed. Teachers in a departmentalized setting might have preferred activity time on Friday.

You cannot have preferred activity time without having fun. Some teachers just naturally have a sense of fun. They bring it with them into the classroom and find ways of making it happen.

Yet, we all would like to have more control over the level of student motivation in the classroom. Understanding and using incentives is, therefore, a necessary part of our professional repertoire. Having fun with learning amounts to enlightened self-interest.

But implementing preferred activity time also must be affordable for the teacher. Work check must be cheap, organization must be simple, and a repertoire of preferred activities must be readily at hand.

Using preferred activities becomes much easier when faculty members work together to gather preferred activity ideas and materials in a central “PAT Bank.” Discovering more and more ways of making learning fun is a hallmark of our professional growth as teachers.

For more information about PAT Banks, please visit http://www.fredjones.com. The book, Fred Jones Tools for Teaching is also available on that site, also available in ebook form.

April 17, 2013

What do you do when a student swears at you?

Staying calm in the face of whiny backtalk is a piece of cake compared to staying calm in the face of nasty backtalk. If we can think of discipline management as a poker game in which the student raises the dealer (you) with increasing levels of provocation, then nasty backtalk is going “all in.” The student is risking it all for the sake of power and control.

What separates nasty backtalk from whiny backtalk is not so much the words, but rather, the fact that it is personal. The backtalker is probing for a nerve ending.

Experienced teachers understand the following rule:

Never take anything a student says personally

If you take what was said personally, you are very likely to be wounded and respond emotionally. If you do, the student has succeeded.

There are two major types of nasty backtalk: insult and profanity.

Insult

There are a limited number of topics that students can use for insults. The main ones are:

• Dress

Say, where did you get that tie, Mr. Jones? Goodwill?

Hey, Mr. Mickelson, is that the only sport coat you own?

• Grooming

Hey, Mr. Gibson, you have hairs growing out of your nose. Did you know that? Whoa, Mrs. Wilson! You have dark roots! I didn’t know you bleached your hair. Hahaha.

• Hygiene

Hey, don’t get so close. You smell like garlic.

Hey, Mrs. Phillips, your breath is worse than my dog’s!

Are you ready to wring the kid’s neck yet? That is the point, after all.

Take two relaxing breaths. When the sniggering dies down, the kid is still on the hook. If you are in your cortex, you can make a plan. Right now, I am not so much concerned with your plan as I am with the fact that you are in your cortex.

Profanity

There are a limited number of swear words that students can use in the classroom. Chances are, you are familiar with all of them. There are your everyday vulgarisms, and then there are your biggies.

Now, ask yourself, what is the real agenda underlying vulgarity? As always, it has to do with power. The question of power boils down to a question of control. Who controls the classroom? This in turn boils down to the question of who controls you.

Can a four-letter monosyllable control you and determine your emotions and your behavior? If so, then the student possesses a great deal of power packaged in the form of a single word.

If you give a high roller this much power, he will use it. And, if such power comes quickly and predictably, he will use it again and again.

To understand the management of backtalk, and especially nasty backtalk, you must conceptualize your response in terms of two time frames, short-term and long-term. As described in last month’s segment, the short-term time frame is very short — two or three seconds.

Short-Term Response

To review, the correct short-term response has to do with the fight-flight reflex. Take two relaxing breaths, remain quiet, and deliver some withering boredom.

If you are in your cortex, you can use good judgment and choose a long-term response that fits the situation. If, however, you are in your brainstem, judgment is out of the question. Consequently, if you succeed in the short-term, you will probably succeed in the long-term.

Your lack of an immediate response is very powerful body language. It tells the student, among other things, that you are no rookie. You have heard it all a thousand times.

If the student runs out of gas and takes refuge in getting back to work, count your blessings, and consider getting on with the lesson. You can always talk to the student after class.

Do not worry that students will think, “Mr. Jones didn’t do anything about Larry’s profanity.” Give them some credit for social intelligence. They just saw Larry try the big one and fail. They saw you handle it like an old pro. And they learned that profanity is useless in this classroom as a tool for getting the best of the teacher.

Long-Term Response

Your short-term response does not foreclose any management options. It simply gives you time to think while avoiding the Cardinal Error.

In the long-term, you can do whatever you think is appropriate. You know your options. If, in your opinion, the student should be sent to the office or suspended, then do it. Just do it calmly.

If you are calm, your actions come across with an air of cool professionalism. You are above the storm.

This calm helps students accept responsibility for their own actions. Of course, that is the last thing they want to do. They would love to have a nail upon which to hang responsibility so it is not their fault. If you are the least bit out of line by becoming upset, you have just provided that nail. However, it is hard for students to blame someone else when they are the only ones acting badly.

If you want to expand upon this information and learn more about the pieces of the puzzle that comprise classroom management skills, read about it in chapter 18 of Fred Jones’ Tools for Teaching. Now available through Amazon in ebook form! www.fredjones.com

April 9, 2013

Open your mouth, slit your throat.

Management of discipline problems in the classroom is first and foremost emotional. You will never be able to control a classroom until you are first in control of yourself.

When you are calm, you can bring all of your wisdom, experience, and social skills to bear in solving a problem. But, when you are upset, you can only focus on the threat that is upsetting you, and your response will be primitive – a fight-flight reflex with an angry voice.

The Cardinal Error in dealing with backtalk is backtalk – your backtalk. The student is talking to you in order to get you to talk to them. If you go for the bait, you’re dead!

When you were four years old, you already had the social skills required to have the last word in an argument if you wanted it badly enough. To watch two children arguing is fairly common. To watch a child and a teacher arguing is disappointing, to say the least – which brings us to our first rule of backtalk:

It takes one fool to backtalk.

It takes two fools to make a conversation out of it.

The first fool is the child, of course. What worries me is the second fool. The second fool is always the teacher. It is the teacher’s backtalk that will get this student sent to the office.

Here is the standard scenario for a student being sent to the office:

• The student mouths off.

• The teacher responds.

• The student mouths off.

• The teacher responds.

• The student mouths off.

• The teacher responds.

• The student mouths off.

By this point in the conversation, teachers usually realize that they have dug their hole so deep that the only way out is to pull rank. That is why backtalk is the most common complaint in office referrals.

Think of backtalk as a melodrama that is written, produced, and directed by the student. In this melodrama, there is a speaking part for you. If you accept your speaking part in the melodrama, it is show time. But if you do not, the show bombs. That brings us to our second rule of backtalk:

Open your mouth, and slit your throat.

Imagine the conversation between teacher and student described earlier if the teacher had had the good sense to keep his or her mouth shut.

• Teacher: Vanessa, I would like you to bring your chair around and get some work done.

• Student: I wasn’t doing anything.

• Teacher: (silence)

• Student: Well, I wasn’t.

• Teacher: (silence)

• Student: Well

• Teacher: (silence)

• Student: (silence)

Students might try to keep the show going for a while, but they cannot keep it going all by themselves. When they run out of material, embarrassment usually sets in. When students begin to feel foolish, they fold. Getting back to work suddenly becomes the quickest way to disappear.

If you talk, you actually rescue backtalkers from their dilemma. It is like mud-wrestling with a pig. You both get dirty, and the pig loves it. And by playing off whatever you say, the student can keep the show alive.

Ironically, no matter how much you may hate backtalk, when you speak, you become the disruptive student’s partner. That brings us to our third rule of backtalk:

If the students want to backtalk, at least make them do all of the work. Don’t do half of it for them!

Think of backtalk as self-limiting. You have to feed it to make it grow. If you do not feed it, it will starve. Or, think of it this way: Opening your mouth is like throwing gasoline on a fire. Do you want the backtalk to die down or blow up in your face?

Beware! Your fight-flight reflex has a voice. It screams in your ear:

You have to do something! Now! You can’t just stand there and take it! Everybody is watching! What are you going to do!??

Your fight-flight reflex is calling you to your doom. Take a relaxing breath. Clear your mind. Hang in there. Chances are, the student will run out of gas.

Regardless of what happens next, most important is the fact that you are calm. If you can think clearly, you can put your intelligence and good judgment to use.

After all, only the students who lack skill are clumsy enough to get into trouble.

March 29, 2013

Enough of the Philosophy – How Do You Do It?

In our first blog, we talked about how Coach John Wooden ran a practice with no lectures or long harangues. We talked about the fact that effective coaching builds performance. We need to look at our end product of a teaching lesson as a performance – something we want the student to be able to do successfully.

Here is a brief introduction of where to start in rethinking teaching as coaching and lessons as building performance.

Giving Corrective Feedback

For starters, corrective feedback must be brief — a simple prompt that answers the question, “What do I do next?” Giving them a prompt for what to do next focuses the student’s attention, while avoiding cognitive overload.

Next, the student must perform the prompt immediately. That avoids forgetting.

At this point, having given them the next step, the teacher needs to move on and let them practice. The eternal enemy of corrective feedback is teacher verbosity.

Jones refers to this series of prompts as Praise, Prompt, and Leave. Check out the full picture in Chapter Six of Fred Jones Tools for Teaching: Discipline, Instruction, and Motivation.

March 27, 2013

March Madness question: How is John Wooden a “natural” teacher?

One of the clearest examples of a master coach is John Wooden, legendary UCLA basketball coach, who won nine national championships in ten years. Wooden would teach an entire move and then break it down into elements. His teaching utterances were short, punctuated, and numerous. There were no lectures and no extended harangues. When researchers analyzed Wooden’s practices, they found that 75% what he taught was pure information, i.e. what to do.

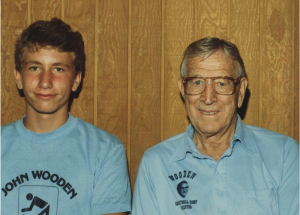

Patrick Jones, co-author of Fred Tools for Teaching, is also a passionate basketball coach. At an early age he experienced Wooden’s coaching as have so many other boys at a John Wooden Camp.

As Jones trains teachers in classroom management, he incorporates Coach Wooden’s skills of effective coaching as they apply to the classroom. The focus is always in building correct performance as efficiently as possible – one-step-at-a-time with immediate feedback.

Coach Wooden did not let players practice bad habits. Instead, he gave them the precision coaching needed to do it right. Teachers will also need a system by which they can build correct performance. As always with coaching, this will involve careful skill building and immediate feedback so that error is eliminated as soon as it occurs.

Patrick Jones with John Wooden at basketball camp, 1985

Pat coaching boy’s basketball 2013