Deborah Swift's Blog, page 20

October 19, 2020

On the Record – The Permanence of History through Fiction #amwriting

“Language is very powerful. Language does not just describe reality. Language creates the reality it describes.” – Desmond Tutu

Mr Swiftstory and I have been watching The Secret History of Writing on TV. If you live in England you can watch this programme on ‘catch up’ and it’s well worth a look. One of the things that surprised me was how places like Turkey changed their written language from Arabic letters to Latinate letters overnight, and how this affected their society. Writing meant the unstoppable spread of ideas, and to me as a writer, this is its first appeal.

The Permanence of Speech

But it’s not only the printed word that is permanent. Yesterday I gave a zoom chat along with some other authors and discovered afterwards that it had been posted on Youtube here. It made me realize that now, even the words you speak – far from being transient, are now indelible on the internet for everyone to see/hear. So they have gained a kind of longevity. (But no-one knows for exactly how long). Making a gaffe could be painful, and worse, it could be around for very long time. So now, instead of the written word being recorded, the spoken word is also being made less ephemeral through podcasts, youtube and other types of recording equipment.

Pic from Encyclopedia Britannica

Pic from Encyclopedia BritannicaThe Urge for Permanence

When we write books, often we are looking to give our words some weight and permanence, and this is why authors love to be published in a paperback or hardback edition. Digital words are only on loan to us, and so the kindle versions of books might be lost to us if no physical copy ever exists. So why do we want our words to be permanent? One obvious answer is, as a salve to the ego. A sort of proof that you were here on Earth and had made a big enough impression to leave a physical object behind.

The Inside Story

Yet its more than that, because books actually come from INSIDE us. They are a form of direct transmission experienced like an intravenous drug from one vein to another. And the fact you have experienced that journey is evidenced by the physical object, the book. This is why we can’t bear to part with books that have meant something to us, even if we never read them again. A novel transports us from the surface to the interior of who we are, and helps us understand why others behave the way they do.

It isn’t just the words but the story they carry. The novel can be a record of lived experience. In fiction the experience is an imagined one. This often makes it more of a reality for the reader than a non-imagined history. When writing A Plague on Mr Pepys, I turned to Daniel Defoe’s book Journal of the Plague Years, even though it was written years after the event and he must have had to re-imagine it all. The re-imagined history was stronger than the bare facts.

Historical fiction seeks to render realities of the past into present lived experience. But will historical fiction be permanent?

Pic by Guillaume Henrotte

Pic by Guillaume HenrotteArchivists will probably not save historical fiction from the fire or flood. They have to decide which documents contain intrinsic value for future generations and so deserve permanence, and often this decision is based on whether the documents are ‘true’ or ‘first-hand’ accounts, and so there becomes a hierarchy of sources:

“One word in the archival lexicon used repeatedly without reflection is the word permanent. Archivists speak almost instinctively of their collections as being the permanent records of an individual or entity. The materials in archives are separated from the great mass of all the records ever created and are marked for special attention and treatment because they possess what is frequently identified as permanent value. Whether by accident or design—and the distinction is at the heart of the modem idea of appraisal—certain materials are selected by archives for preservation into the indefinite future. They are in that sense permanent.’’

On the Idea of Permanence – James M O’Toole American Archivist 1989

Re-presentation

Our interpretation of the past shifts with every generation, so historical fiction needs to tap the archives anew for new fresh ways of re-presenting the same stories from history and then by making sure those interpretations are as widely available as possible.

In the programme The Secret History of Writing, much was made of the impact of printing on the permanence of ideas.

The Massachusetts Historical Society declared in 1806:

“There is no sure way of preserving historical records and materials, but by multiplying the copies. The art of printing affords a mode of preservation more effectual than Corinthian brass or Egyptian marble.”

So by printing multiple copies, we ensure that our re-presentations of history are never lost, even if archivists don’t save it, and despite any dystopia where there is no wifi, electricity, or wind-up radio.

The post On the Record - The Permanence of History through Fiction #amwriting first appeared on Deborah Swift.

October 12, 2020

‘Changing the dream’ – An interview with author Joan Schweighardt #ecology

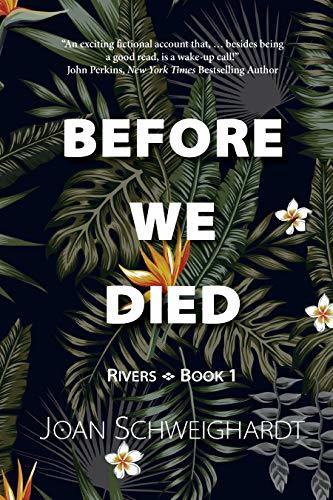

I am thrilled to welcome Joan Schweighardt, author of The River Series to my blog today, to talk about her fascinating journey into the rainforests of South America and how it inspired her books.

I am thrilled to welcome Joan Schweighardt, author of The River Series to my blog today, to talk about her fascinating journey into the rainforests of South America and how it inspired her books.

Hi Joan, first off, tell me about your travels to South America and what made it an ideal setting for your historical novels.

My journey actually began with a freelance job I did for a local publisher wherein I was asked to read backlist books and write a short piece on each for their website. One of the books was a slim annotated presentation of the edited diaries of a rubber tapper (from Brooklyn, NY) working in the Brazilian rainforest in the early 1900s. I read it twice and afterwards I began to research the South American rubber boom to learn more. Then one evening I found myself watching a PBS special in which a journalist traveling through the South American rainforest asked an indigenous shaman what “northerners” could do to help save the rainforest from the constant threat of destruction, particularly from oil drilling. The shaman said we northerners could “change the dream.” What did that mean? I googled the phrase and found those same words used as a tagline by a not-for-profit called Pachamama Alliance. In exchange for supplying legal support to indigenous tribes hoping to push back on oil companies, the tribes were allowing small groups of people traveling with Pachamama principles to visit their villages and learn about their way of life. I signed up. My experience was life-changing. As soon as I got home I began researching for what would become the first of three novels connected to South American rubber boom.

When I finished the first draft of book one, I went to South America again, this time to Manaus Brazil, which was the headquarters for the rubber boom. I visited the city and then spent several days on a small boat with a private guide to see, among other things, rubber trees.

The natural world of the rainforest and the challenge of how to use its resources seems to be a theme in your books. What fact or feature about the rainforest did you find the most surprising?

Virtually everything. I went in curious and came out shocked. I didn’t know, for instance, that during the boom, rubber barons began enslaving indigenous people to tap for rubber, because the men they recruited were dying left and right…from snake bites, malaria, starvation, all things the indigenous people know how to avoid.

Did you think you would be writing a trilogy when you first set out, or did the other two books grow from the first? What gave you the impetus to keep the story alive?

Did you think you would be writing a trilogy when you first set out, or did the other two books grow from the first? What gave you the impetus to keep the story alive?

I was so impacted, not only by my two trips to South America but by all that I was learning about the rubber boom, the history of Manaus, the flora and fauna of the rainforest, its indigenous inhabitants, etc., that my pleasure in the project would not confine itself to one book. As I wanted to stay immersed, I kept writing.

Tell me about the different protagonists in your books. In the first book the main character is a man, and in the third the story has more focus on the daughter; how has this made this third book different from the first ?

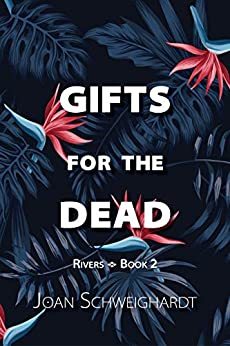

Actually all three books have different protagonist narrators and two are women. The first book, Before We Died, is narrated by Jack Hopper, an Irish American dock worker from the New York area who travels with his brother Baxter to the rainforests of Brazil where they become rubber tappers. The second book, Gifts for the Dead, is narrated by Nora Sweeney, the young woman who is the love interest of both brothers in book one and who marries Jack Hopper in book two. The third book is narrated by Estela Euquério Hopper, Jack Hopper’s daughter. Collectively, the story spans 1908 to 1929.

How much does the world of the rainforest impact on the psychology of your main characters, and how much does New York have in common with the rainforest?

Each of my three narrators is affected differently by the rainforest. Jack Hopper cannot help but see it in terms of its inherent dangers and the tremendous losses he suffers there. Nora is affected by the beauty of the rainforest and the sense of balance she discovers in herself during her time there. Estela is born and raised in Manaus, Brazil. Her ancestors on her mother’s side are a mix of European and Indian blood. For her, the rainforest is home. The tie to New York is that Jack and Nora Hopper live there—actually they live in Hoboken, New Jersey, just across the river from Manhattan. They make trips to Brazil in both books one and two. In book three, Estela travels to New York.

How does Opera feature in your new book?

As the worldwide demand for rubber increased in the late 1800s, would-be rubber barons realized that the sleepy fishing village of Manaus, located at the center of the world’s largest rubber-yielding rainforest, was perfectly positioned to become the headquarters for the industry. Europeans came in droves to take advantage of the financial opportunities the industry promised. There was nothing there, so they built mansions, hotels, restaurants, shops, all with tile and marble and even bricks from Europe. The centerpiece of their construction was the Teatro Amazonas, the opera house, completed in 1896. For some years the Teatro Amazonas was operational, though many opera stars became ill traveling to it. Then, in 1912, the rubber boom in the region came to an abrupt end—because rubber plantations had begun to produce in English territories in Southeast Asia—and the Europeans fled Manaus en masse. The Teatro Amazonas became a symbol of failure.

In River Aria, a Portuguese voice/music instructor comes to Manaus post boom, with the intention of teaching opera to some of the “river brats” from the city’s poor fishing community, and local officials allow him to use the grand lobby of the Teatro Amazonas for his instruction. Estela, Jack Hopper’s daughter, is one of his students.

In River Aria, a Portuguese voice/music instructor comes to Manaus post boom, with the intention of teaching opera to some of the “river brats” from the city’s poor fishing community, and local officials allow him to use the grand lobby of the Teatro Amazonas for his instruction. Estela, Jack Hopper’s daughter, is one of his students.

In the process of writing, what matters to you personally as a novelist the most?

I want to have an intense writing experience and of course I want readers to have an intense reading experience.

Brief Biography:

Joan Schweighardt is the author of eight novels, a memoir, two children’s books and several magazine articles.

“The author transports us to a fascinating, hardscrabble, well-researched world, and compels us to want to live there for every word … I just love this story.”

—Lynn Vannucci, Publisher, Water Street Press

The post 'Changing the dream' - An interview with author Joan Schweighardt #ecology first appeared on Deborah Swift.

October 4, 2020

Never A Cross Word – The history of crosswords with Liz Harris

I’m thrilled to welcome Liz Harris to my blog today to enlighten us about crosswords. Over to Liz!

Liz Harris

Liz HarrisIf you heard someone claim that in their relationship that they’d never had a cross word, you’d raise your eyebrows in disbelief. ‘Pull the other one!’ you’d exclaim. At least, I would. And had ‘cross’ and ‘word’ been joined together, your response might still have been the same.

A lover of cryptic crosswords, I’d rather assumed that there’d never been a time when newspapers hadn’t included a crossword. But I was wrong. The first known published crossword that shared features with crosswords today, appeared in a Sunday newspaper, the New York World, in December 1913.

I discovered this when planning a verbal exchange between Charles Linford and his wife, Sarah, characters in The Flame Within, a novel set in the 1920s. I saw bored banker Charles as the sort of man who’d do a crossword when hidden away in his office. Before writing their exchange, I thought I ought to check that The Times, the newspaper I wanted Charles to be reading, did indeed have a crossword. To my surprise, it didn’t. Curious, I found myself looking back into the development of the crossword.

The WordCross

The word-cross, as it was then called, which first appeared in New York World, had been created by one of their journalists, Arthur Wynne, who’d been born in Liverpool. Wynne’s word-cross was published in the newspaper’s eight-page ‘Fun’ section as a mental exercise. An illustrator later reversed ‘word-cross’, which became ‘cross-word’.

Above: Fun’s First Crossword Puzzle, by Arthur Wynne, in New York World.

Above: Fun’s First Crossword Puzzle, by Arthur Wynne, in New York World.

The diamond shape being eye-catching, and the clues easy, it was an instant hit with readers, and what seems to have been intended for children or as a light bit of fun, gradually developed into a serious adult pastime. Within ten years, most American newspapers included a crossword.

The first puzzles didn’t have any internal black squares, but as they became more popular, they developed the form with which we’re familiar – a grid made up of black and white squares, with all the white squares appearing in horizontal rows or vertical columns, but not always separated with black squares.

Anyone who’s done an American crossword knows that they’re different in style from crosswords in the UK. In the US, every letter is part of both an ‘across’ word and a ‘down’ word, and there are usually at least three letters in every answer. Shaded squares form about one-sixth of the total. Whereas, on average a traditional crossword grid in the UK has about 25% of shaded squares, and half the letters in an answer are unchecked.

So when did crosswords reach the UK?

Forms of crosswords had existed in Britain in the 19th century. These were derived from the word square – a group of words arranged with the letters reading both vertically and horizontally – and they were printed in children’s puzzle books and periodicals. There are differences of opinion about the exact date of the first appearance in a newspaper of a crossword as we know it, but there was certainly one in Pearson’s Magazine in February 1922, in the Sunday Express in November 1924, and in The Times in February 1930. The word ‘crossword’ first appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1933.

Unlike in the US, cryptic crosswords took hold in Britain, and rapidly gained in popularity. A famous cryptic crossword enthusiast was none other than Inspector Morse. His creator, Colin Dexter OBE, was a huge fan of cryptic crosswords, and delighted in characterising Morse as such, too.

A Love of Crosswords

Some years ago, I was introduced to Colin Dexter at a party given by the Oxford Writers’ Group. During our conversation, much of which focused on The Archers, we found that we both loved cryptic crosswords. A few days later, Colin gave me a book he’d written, Cracking Cryptic Crosswords, and he gave a talk at the Waterstones Oxford launch of my debut novel, The Road Back.

Liz Harris and Colin Dexter

Liz Harris and Colin DexterMy favourite cryptic crosswords are those in the Daily Telegraph, but rather than buy the newspaper, I buy their books of cryptic crosswords. The first book of crossword puzzles was published by Simon & Schuster in 1924, following a suggestion from co-founder Richard Simon’s aunt. Initially sceptical about the book, Simon printed only a small run at first, promoting the book by attaching a pencil to it. To his amazement, it was an instant hit.

Characters and crosswords

Characters and crosswordsI was determined to use what I’d found out about crossword puzzles in the body of The Flame Within, and this is how I used it. Sarah Linford is nagging her husband, Charles, over his lack of ambition, as she habitually did at breakfast:

‘That’s you all over, Charles—anything for an easy life.’ Sarah spread a thick layer of butter on her toast, her movements brusque. ‘Reading the Daily Express says it all,’ she added, nodding towards his newspaper. ‘Most people in your position would read The Daily Telegraph or The Times. On second thoughts, not The Times. I dislike the way they were all in favour of the war, and also their comment three months ago that Jewish people were the world’s greatest danger. That was quite appalling. No, The Daily Telegraph should be the paper of choice for someone like you.’

‘But it doesn’t have a crossword, does it? Whoever came up with the idea of a crossword in a newspaper is a genius. By having the Daily Express, when I’m bored in the day, all I have to do is take out my paper and do the crossword.’

‘Ah, but if you read The Daily Telegraph, you might see an advertisement for a job that would actually challenge you, and interest you, so there’d be no need to kill time with a crossword.’

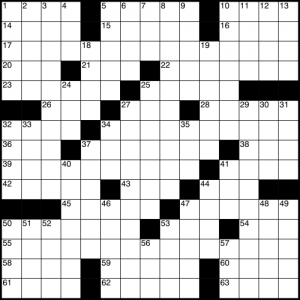

Liz’s just started crossword is above. Hope she solved it all!

About The Flame Within

LONDON 1923

Alice Linford stands on the pavement and stares up at the large Victorian house set back from the road—the house that is to be her new home.

But it isn’t her house. It belongs to someone else—to a Mrs Violet Osborne. A woman who was no more than a name at the end of an advertisement for a companion that had caught her eye three weeks earlier.

More precisely, it wasn’t Mrs Osborne’s name that had caught her eye—it was seeing that Mrs Osborne lived in Belsize Park, a short distance only from Kentish Town. Kentish Town, the place where Alice had lived when she’d been Mrs Thomas Linford.

Thomas Linford—the man she still loves, but through her own stupidity, has lost. The man for whom she’s left the small Lancashire town in which she was born to come down to London again. The man she’s determined to fight for.

Website: www.lizharrisauthor.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/lizharrisauthor

Twitter: @lizharrisauthor Instagram: liz.harris.52206

The post Never A Cross Word - The history of crosswords with Liz Harris first appeared on Deborah Swift.

September 25, 2020

Death in Delft by Graham Brack – a #17thCentury murder mystery

This is the first Master Mercurius novel I’ve read, but it won’t be the last. Set in the immaculately detailed setting of 17th Century Delft, Master Mercurius is a character it is easy to warm to. An undercover priest as well as a protestant cleric, he is keen to do the right thing in the spirit rather than the letter of the law, and has a dry sense of humour that is a good foil for the beastly business of solving murders.

In this case we have a dead girl and some other missing girls we fear for, and it’s a race against time for Mercurius to discover and flush out the kidnapper, before the dastardly murderer kills another.

One of the joys of this book is all the supporting characters we meet along the way. We get an intimate view of Vermeer described as having: an intensity of gaze I found unsettling, as if he really saw all there was to see, open or concealed.

We also get a view of scientists of the time such as the ‘polite’ Van Leeuwenhoek who is just experimenting with lenses to view what lives in our saliva – to Mercurius’s amazement. Of course there are plenty of clues for him to follow and a satisfactory wrap-up to the plot.

A well-researched, tightly-plotted treat. I highly recommend, and will be reading another soon.

The post Death in Delft by Graham Brack - a #17thCentury murder mystery first appeared on Deborah Swift.

September 20, 2020

Author in Search of a Character – Why James Burke?

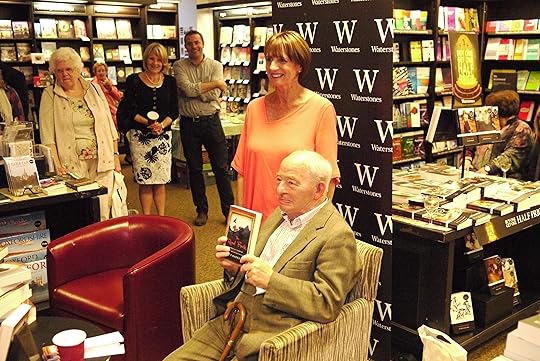

I’m delighted to Welcome Tom Williams to my Blog today to tell us about how he came to write the Burke series, described succinctly by Paul Collard as ‘James Bond in Breeches.’ Over to Tom:

I’m delighted to Welcome Tom Williams to my Blog today to tell us about how he came to write the Burke series, described succinctly by Paul Collard as ‘James Bond in Breeches.’ Over to Tom:

Why James Burke? Would it make any sense to say I did it for the money?

If I’m being honest, it can’t really have been for the money, because I know that writing fiction (and particularly historical fiction) is never going to make you rich. But I started writing about Burke as a (sort of) commercial exercise.

Let me explain.

My first novel was The White Rajah. It was based on the life of James Brooke, the first White Rajah of Sarawak. Like most would-be novelists with my first book, I desperately wanted to write the Great British Novel. I was fascinated by Brooke’s character and the history of how he had come to rule his own kingdom in Borneo and I tied this in with ideas about colonialism and the morality of British rule around the world. Just in case I hadn’t weighted the book down with enough “significance”, Brooke was almost certainly gay and there’s a whole subplot about that. And, as the cherry on the cake, the whole thing is written in the first person and (given that this first person was writing in the mid-19th century) not in the most accessible language.

Despite this, I got an agent! And the agent got rejections from every major publisher he approached. It was, they all claimed, “too difficult” for a first novel. “Why don’t you,” he suggested, “write something more accessible? Still historical, but more the sort of thing people are going to want to read?”

I was stumped. I asked friends for ideas. I even asked Jocelyn, an Alaskan tango dancer I’d met in Buenos Aires (as you do).”Why don’t you,” she said “write about the early European settlers in South America? They have some brilliant tales to tell.”

Jocelyn does not like stories with a lot of violence. I think she was looking more at the explorers and the politicians, or even the ordinary people who left Europe in vast numbers to build a new world in the New World. But when I started randomly looking for European figures in the early colonial history of South America, the one who caught my eye was James Burke.

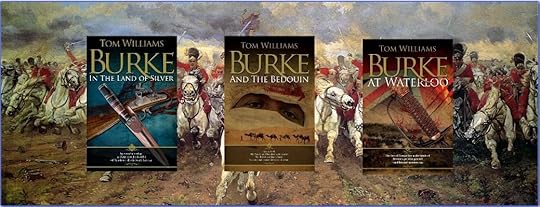

Burke was a soldier, but we have good reason to believe that he spent most of his time as a spy. The first book I wrote about him, Burke in the Land of Silver, is very close to his true story. Sent to Buenos Aires to scout out the possibility of a British invasion, he explored what is now Chile, Peru and Bolivia, returning to Buenos Aires to assist with the British invasion when it finally came.

Burke was a soldier, but we have good reason to believe that he spent most of his time as a spy. The first book I wrote about him, Burke in the Land of Silver, is very close to his true story. Sent to Buenos Aires to scout out the possibility of a British invasion, he explored what is now Chile, Peru and Bolivia, returning to Buenos Aires to assist with the British invasion when it finally came.

I’ve obviously never met Burke, but the little we know about him still gives a strong idea of his character. He was an Irish Catholic who had joined the French army because the British Army did not offer an impecunious Irishman much possibility of advancement. We know he was something of a snob, at one stage changing his name to something that sounded more prestigious than Burke. He ingratiated himself with rich and powerful men, but he does seem to have been good at his job. In any case, there was a James Burke on the Army list long after the Napoleonic wars were over, so he did seem to be kept busy doing whatever it was that he was doing.

It’s this uncertainty about his career that makes him an ideal candidate for a series of books. (If you want to sell nowadays, it’s best to write a series – like Deborah’s excellent trilogy based around Pepys’ life.) He was a spy. He moved in the dark and nobody is quite sure what his missions were. So I can make them up. And what a brilliant period of history it is to make up spy stories about. I’m in a long tradition of sales of derring-do about spies during the wars with France, from the Scarlet Pimpernel to O’Brian’s Stephen Maturin and Iain Gale’s James Keane.

Each Burke story is set around a different Napoleonic campaign. After the British invasion of Buenos Aires (Burke in the Land of Silver) we see him in Egypt’s during Napoleon’s invasion that country (Burke and the Bedouin) and in Paris and Brussels during Napoleon’s textile and returned to power (Burke at Waterloo). The latest story (though not told in chronological order) finds him fighting in the Peninsular War, specifically around the battle of Talavera.

The Burke of Bedouin and Waterloo is entirely fictional, but his adventures in the peninsula are based on another real-life spy, Sir John Waters. In all the books, whether Burke’s adventures are entirely fictional or based on fact, the military and social background is as accurate as I can make it. In fairness I can’t make it all that accurate, but I have gradually found a network of people who really understand the Napoleonic Wars and who have been generous enough to share their understanding with me.

I like James Burke as a hero because he is often far from heroic. Cynical, snobbish, and an inveterate womaniser with an eye for the main chance, it’s easy to dismiss him as an arrogant officer who relies on the solid good sense of his servant, William Brown, to achieve anything. But Brown will be the first to disagree with you, pointing out that when the chips are down Burke will, often reluctantly, always do the right thing. The fact that the right thing isn’t always what his military masters would want him to do, just makes it more interesting. When push comes to shove, he is not only physically but morally brave.

I have come to be quite fond of James Burke. His next adventure will see him in Ireland in 1793 where he is charged with infiltrating the Irish nationalist movement. Perhaps this early mission explains much of his cynicism, for it is his darkest and most morally dubious adventure in the series. But that’s to come. For now, we can relax and enjoy the fun as his schemes, fights, and romances his way through the chaos that is the Peninsular War.

Burke in the Peninsula will be published on 25 September. It is available on Amazon at £3.99 on Kindle and £6.99 in paperback.

You can read more by Tom Williams on his blog, http://tomwilliamsauthor.co.uk/. His Facebook page is at https://www.facebook.com/AuthorTomWilliams and he tweets as @TomCW99.

And The White Rajah did eventually see publication and is worth your time. Here’s the link: mybook.to/TheWhiteRajah

The post Author in Search of a Character - Why James Burke? first appeared on Deborah Swift.

September 19, 2020

Introverts and Extroverts in Historical Fiction

Photo Credit: Wikipedia Frank Kovalchek from Anchorage, Alaska, USA

Photo Credit: Wikipedia Frank Kovalchek from Anchorage, Alaska, USAI recently came on a discussion in a facebook group about introverts and extroverts in fiction. (Sorry to whoever started this thread; I can’t find it again now!) But it really made me stop and think, because as a reader I have always been a fan of what I call ‘quiet books’. The more page-turning a book is, the less memorable. So as a writer I need to find a balance between the speed my reader devours the book, and the feeling or memory that the book leaves behind, both of which rely on slowing the pace.

Stakes

The fashion these days in books on the craft of writing is to tell you to concentrate on high action and drama and to have plenty at stake in an external way. This is what we see a lot of in film and TV drama, when the focus is on the physical demonstration of action. In these media, it’s necessary because we have no access to the interior thoughts of the characters.

But novels are different, and as a novelist I’ve always been much more interested the in motivation of my characters. They act, but not necessarily in a high stakes way. The suggestion that some readers might prefer to read about introverted characters, but that most fiction is aimed at extroverts, is a refreshing idea.

What is an introvert, and what might they want to read?

According to Healthline Carl Jung wrote that introverts and extroverts could be separated based on how they regain energy. Introverts prefer a less stimulating environment, and need time on their own to recharge their energy levels, whereas extroverts recharge by social interaction and being with other people.

It made me wonder if introverts prefer reading books written in the first person, where the ‘I’ conveys the inner feelings of the protagonist, and it is as if you are the only person through whom the story is being told. Perhaps a more extrovert reader would prefer multiple points of view and multiple characters which would mimic their preferred way to refuel?

Drawing Room Drama

In historical fiction, the history that has survived is often of the ‘high stakes’ variety. War, bitter battles for control over crown or state, murderous religious divides. Yet one of the most enduring historical fiction periods is the Regency period, presided over by the giant Jane Austen, whose quiet wit, and focus on the drawing room intrigues of societies marriage market, prove endlessly popular.

The Spectrum

As a reader I enjoy both types of fiction, but I couldn’t read an endless diet of historical thrillers. The non-stop breathless action makes me long for a quieter book. I suspect that like most readers, I am on the spectrum between introvert and extrovert, but heading more towards the introvert. As a writer, I need to recharge often after my most dramatic scenes, as I am literally living them as I write.

What do you think? Are you an introvert or an extrovert? Do you like to read about introverted characters, or must they always be the ‘go-getting’ adventurous type? What type of books do you like to read, and would you categorize yourself as an introvert or extrovert?

The post Introverts and Extroverts in Historical Fiction first appeared on Deborah Swift.

September 18, 2020

Historical Fiction – the joy of writing extraordinary commoners

I’ve just started a new book and after quite a bit of research, this is the first week of actually typing anything for my new project, book two of a series set in Italy. I’m a pantser, so I just launch straight in and then try to write my first draft as quickly as possible, and allow a lot of time afterwards for editing, refining and re-structuring the story. I have an overarching view of the story in the form of two sheets of A4 paper which are my only outline, plus of course the memory of what happened in Book 1. So far this week I’ve managed just over 7000 words, which is average for me. It gets slower as the story develops in complexity and as I figure out where the characters are taking me and what new research I need to do.

The piles of books on my desk (above)represent the things I am working on. On the left – things I’d like to write about – the writing wish-list. In the middle, books about my last series (in case anyone asks me awkward research questions!) and the next two piles are books about the stories I’m working on right now. There’s a lot about poisons as my main protagonist is a poisoner.

Again, the second book in my ‘Italian’ series is about a commoner. Publishers are often keen that novelists should write about ‘marquee names’ – which means to say people they’ve heard of. They know they can sell any number of books about Anne Boleyn. If the book is about someone people have heard of, its much easier to sell.

This is not actually true. The Girl with the Pearl Earring sold well, despite having an unknown woman at its heart. As did The Miniaturist. Besides, Royal courts have never much interested me. Instead I’m interested in individuals who have made their mark in history despite being supposedly ‘nobody special.’ My job as a novelist is to make them special and unforgettable. This is a joy, as unlike Anne Boleyn, where there are thousands of interpretations of her life, each of my characters can shine out from her historical past like a gem in a very direct way.

The three women I wrote about from Pepys’ Diary were women he mentioned in passing. Yet now I have re-imagined rich and vibrant lives for Deb Willet, Bess Bagwell and Mary Elizabeth Knepp. You won’t know who they are because they are footnotes in history. The only portrait of them that exists, is in Pepys’ Diary and my books, and so to me these characters are unsullied by other interpretations. I got to know them through my own internal imagination and Pepys’ direct descriptions rather than through some other biographer’s lens. These women now live as more than footnotes and have been given imaginary voices, and I hope voices that concord with their status in the period.

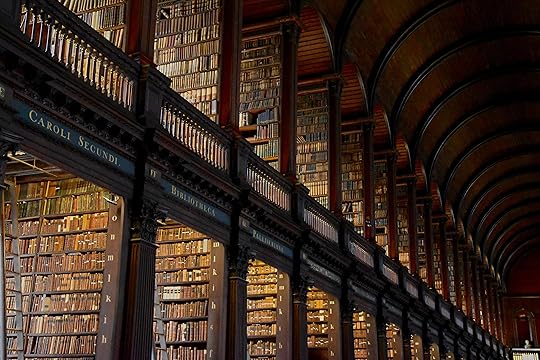

Pepys Library in Cambridge

Pepys Library in Cambridge

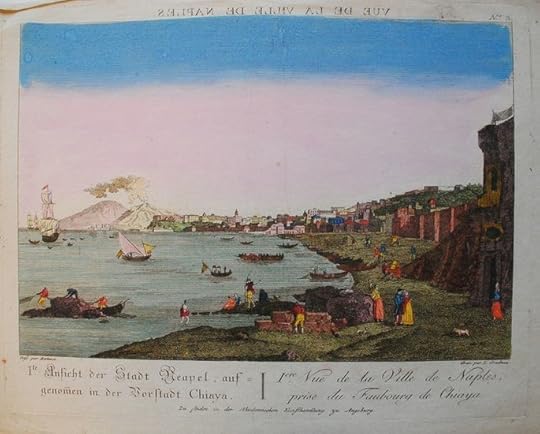

Because of the fact my characters have no biographers, my research is mostly background. I read very few books that pertain directly to my main characters. I love old maps and take great care with the settings to make them as authentic as possible. Here’s one of old Palermo I used in Book I of my new series. Historical events, and their impact on the people in my stories are my main interest. The cities of Palermo and Naples at that period was subject to earthquakes, rebellions and the eruptions of Mount Vesuvius. Politics always looks very different from the bottom, rather than from the point of view of those who make the decisions.

My new series is based around the life of Giulia Tofana, an Italian 17th Century poisoner. She allegedly killed 600 men in the cities of Rome and Naples. She is half legend, half real person. Her story has been embroidered and changed over the centuries, but no-one has written a biography of her. So I had to find an internal way to bring her to life, and one of the ways I attempt to do that is to give her a strong setting, and within that to furnish her with a strong set of opinions. For her poisonings to be convincing, her view of the world has to be skewed in some way by her life’s events. In the first book we see these events brought to life, but by book 2 she is now in a very different situation. From being a courtesan in the first book, she now finds herself a nun in charge of a family of young women incarcerated against their will.

The first novel in the series, ‘The Poison Keeper’, is finished and has been contracted to Sapere Books for publication early in 2021. In my first week writing Book 2, I’m wrestling with how much backstory a new reader needs to jump them into the story. I’m also researching the history of the silkworm which will play a big part in the unfolding events. And as always I’m enjoying breathing life into Giulia Tofana, a woman who has not yet been voiced in an English-speaking novel.

Thank you for reading. Comments welcome.

My new WW2 novel will be published soon, and my latest book is here

The post Historical Fiction - the joy of writing extraordinary commoners first appeared on Deborah Swift.

September 15, 2020

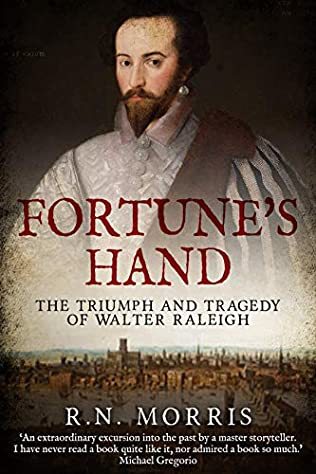

Fortune’s Hand – a novel of Walter Ralegh

The Boyhood of Raleigh 1870 Sir John Everett Millais

The Boyhood of Raleigh 1870 Sir John Everett MillaisI knew nothing about Walter Ralegh, except the legends I’d been told at school; about how he lay down his cloak for Queen Elizabeth I. Was this legend true? Read more here on History Extra to find out.

In his novel, Fortune’s Hand, R N Morris treats us to a visceral interpretation of Ralegh’s life. This is an extraordinary novel. We experience it from multiple points of view, from the acorn that will grow to become the oak timbers of the ship he will sail in, to the teeming life within an old ship’s biscuit. Much of Elizabethan life on board ship is ugly and brutal. We are shown a thief having his hand cut off, and later we witness a massacre in Ireland, and wince at the way a horse might pick its way across a corpse-strewn field. Yet the writing of it is always lyrical, and Morris gives these events a strange kind of beauty. What impresses is that Raleigh experiences these things as part and parcel of his life – to him they are every day occurrences. We are really treated to the mind-set of an Elizabethan man.

Ralegh is of course obsessed with gold, and we see his ambition and his turbulent relationship with the Queen. Yet his literary ambitions are also on show – the novel includes a whole scene after a tennis match written in blank verse, where the dialogue zips back and forth like a tennis ball as if we are in a Shakespeare play. Above all, this is a novel that explores what it is to be a historical novel. It is unlike any other historical novel of the period, and its skilful research and execution are much to be admired.

The post Fortune's Hand - a novel of Walter Ralegh first appeared on Deborah Swift.

September 14, 2020

Ten authors you should know about, who write about the 17th Century #HistFic

The Seventeenth Century is undergoing a bit of a revival, with best-selling authors like Philippa Gregory and Tracy Borman, all getting in on the act. Here is my first of two posts recommending authors who write about this period in European history.

Of course in England the 17th Century is rich pickings with the over-turning of the monarchy, a bitter civil war, new advances in science and medicine, not to mention the witch-hunts and religious persecutions. And London, England’s capital was besieged by war, plague and fire.

But there are many other authors writing about this period whose books should not be overlooked. Here’s a list of ten I can heartily recommend. Click on their names to find all their books.

L.C Tyler – the John Grey mysteries are wonderful who-dunnits and there is a lovely wit and irony to these books.

Alison Stuart – Her Guardians of the Crown series set in the English Civil Wars is full of swashbuckling, difficult choices, and romance.

M J Logue – Her ‘Uncivil War’ series and her Thomazine and Major Russell books have an insider’s view of the period and great characters.

Anna Belfrage – if you like time-travel you will enjoy being transported back to 17th Century Scotland in her gripping nine book series The Graham Saga.

Graham Brack – The Master Mercurius books of the 1670’s featuring a cleric who is both Catholic and Protestant are intricate well-researched mysteries with a dash of humour.

Cryssa Bazos – Her acclaimed romances in the ‘Knot’ series are much more than that. Expect impeccable research plenty of action and a thrilling ride.

Elizabeth St John – lovingly authentic reconstruction of a family’s difficulties through the 17th Century, rich with the real intrigue and political strife of the day.

J G Harlond – The Chosen Man Trilogy is chock full of seafaring, spies and treachery in the 1630s and beyond.

Linda Lafferty – her books about Caravaggio and Atremisia Gentileschi shows us the 17th Century movers and shakers in the art world.

Pamela Belle – The Heron Quartet and The Wintercombe Series provide us with fantastic insights into the life of the English Manor and the changing allegiances of its inhabitants during the 17th Century.

The post Ten authors you should know about, who write about the 17th Century #HistFic appeared first on Deborah Swift.

September 6, 2020

Two books with #WW2 connections

Of Darkness and Light is an engaging mystery of art and artists set in WW2 Norway. Heidi Eljarbo has certainly given herself a challenge – to write two historical periods in one novel which flow seamlessly from one to another, but the narrative works well and the two timelines inform each other beautifully. We begin the story in WW2 Norway where Soli works in an art shop. We see the shock of the invasion of Norway by the German army and what that means for Soli’s close family and friends.

Of Darkness and Light is an engaging mystery of art and artists set in WW2 Norway. Heidi Eljarbo has certainly given herself a challenge – to write two historical periods in one novel which flow seamlessly from one to another, but the narrative works well and the two timelines inform each other beautifully. We begin the story in WW2 Norway where Soli works in an art shop. We see the shock of the invasion of Norway by the German army and what that means for Soli’s close family and friends.

As the book progresses, the art shop where Soli works is frequented by Nazi collectors of fine art, although the owner does his best to hide the most precious works from these men. When a murder happens right outside the shop, Soli finds herself irresistibly drawn into the mystery of who killed her colleague and why, and the puzzle deepens when Soli discovers that the victim, who she thought she knew well, is also known by another name.

At the same time a painting is missing from auction and Soli must uncover what has happened to it before the Nazis do. I can’t reveal too much of the plot without revealing all the twists and turns, but suffice it to say, Soli and her Art Club are drawn into the Resistance in their bid to save the art world’s cultural heritage from being stolen by the Nazis. Soli is an engaging protagonist, with the skill to tell a real painting from a fake, and the author makes the most of Soli’s ‘eye’ in giving us detailed descriptions of people and places. The reveal of what is inside the walnut and gilded frame is a highlight for me in descriptive writing.

As well as finely drawn detail within WW2 Norway, We are taken back to 17th Century Valetta, Malta, to the studio of Michelangelo known as Caravaggio, and his model Fabiola, again all described in sumptuous detail. If you love the art world and a good mystery, you will really enjoy this well-written book which has plenty of excitement and intrigue to keep you turning the pages.

Find out more about Heidi and her other books.

Endless Skies by Jane Cable is a contemporary romantic novel that harks back to memories of WW2. Archaeologist Rachel Ward’s relationships with men have always been a disaster. Short-lived, and lacking in commitment. This novel begins to unlock why by gradually letting us into her past. Brought up by her grandmother, Rachel has a natural empathy with Esther, an elderly woman in a care home near where she is working. I really enjoyed the character of Esther, and thought she was drawn well without too much sentimentality.

Endless Skies by Jane Cable is a contemporary romantic novel that harks back to memories of WW2. Archaeologist Rachel Ward’s relationships with men have always been a disaster. Short-lived, and lacking in commitment. This novel begins to unlock why by gradually letting us into her past. Brought up by her grandmother, Rachel has a natural empathy with Esther, an elderly woman in a care home near where she is working. I really enjoyed the character of Esther, and thought she was drawn well without too much sentimentality.

The men in Rachel’s life are the dreadful, manipulative Ben, one of her students, and Jonathan, who is a property developer. An affair with Ben was always going to be a bad idea, but it also causes Rachel to look back at why she always makes such bad choices. Jonathan asks Rachel to do some work surveying what used to be a local airbase. This links up to Esther’s story, but I won’t give too much away.

One of the delights of the book is the atmospheric setting of the flat Lincolnshire countryside, and the deserted airfield which contributes to the idea that the ghosts of the past still have a bearing on what happens in the present. A thoroughly enjoyable read with multiple interesting strands.

Read more from Jane about the book.