Ann Pearlman's Blog, page 6

January 3, 2013

How I Write

I’m often asked how I write, how I am sufficiently disciplined to actually get books completed, so I thought I’d share some of my tricks and routines.

First, I’ve been writing since eighth grade, jonesing for the feeling I received completing an assignment. We were asked to write thank you notes for a painting our school received. The painting was of two girls sitting on a beach, behind them was the sea, stretching to the horizon. As I wrote about the sea I was transported into a sensation of taking dictation from the universe. Re-experiencing that sensation propels my writing. I write because I love it; I write because I want that feeling again. Weeks later, when I’m editing, I cannot tell which prose was awe-inspired and which was written prosaically.

For years, I didn’t have the luxury of writer’s block, stealing time to scribble notes in between my job, and running my kids around various activities after school. Each moment stolen to write was precious.

Then I discovered the glory of automatic writing: Get up early, before anyone else is up, and immediately write, do not edit yourself, just inscribe the words that come to you. The only experience between dreams and writing were brushing my teeth and coffee. My language was richer so I habituated myself to write first thing in the morning. Slowly, I rescheduled my life around my writing, instead of pushing it between the edges of my other requirements. My kids growing up made that easier.

So I wake with the sun. I write at least five days a week. At least four hours a day. I don’t let myself be interrupted until I’ve done several hours. Then I’ll eat breakfast, answer calls, emails, twitters, etc.

Other tricks: I have words that I have forgotten, igonored in a bowl. I notice them once again in something I’ve read, write them down, and put them in a bowl. Occasionally, I pick one out to flutter (see, that was one…) into my prose.

If I get stuck, I drum. Yes, I play a Djembe hand drum and the repetitive rhythm seems to encourage ideas. So does jumping up and down on a trampoline.

I work out. This is important. After years on the computer, if I didn’t work out, do yoga, and use an ergonomically correct keyboard, I suspect I’d be crippled by carpal tunnel syndrome.

Music provides an added layer of texture to my setting. Writing Inside the Crips, I listened to the hip hop and gangsta rap ( Snoop Dog, Ice T, N.W.A. ) that set the rhythm and the texture of Colton’s life. Writing a scene that takes place in Detroit in the 70’s, I listen to The Jackson 5, Aretha Franklin, Martha Reeves, etc. Sometimes when I’m writing, sometimes when I’m driving or working out my ipod surrounds me with sounds that ebb the time and place into my soul. I ended up so entranced by the rhythm and rhymes of rap that Tara in A Gift for My Sister became a rap artist.

Writing is as much a part of me as breathing. Writing, even if it’s in my journal, imparts meaning to each day.

The piece first appeared as a guest post on Girl Who Reads. It was the sixth most frequently read blog of 2012. Thank you, Donna.

December 10, 2012

A Different Cookie Club this year

Last Monday, we had our cookie exchange, and I was sick! I sat in a corner so I didn’t infect my friends, passed out my goodies and left heartbroken to miss one of the highlights of my year. Any of you who’ve read The Christmas Cookie Club have a sense of how much fun the cookie exchange can be!

This year, especially, I started thinking about the party as soon as the watermelons were ripe. Why watermelons? What do they have to do with Christmas? Well my favorite Christmas treat is fruitcake and a particularly delicious one contains sweet pickled watermelon rind. For years, I preserved the rind in August, baked the cakes the weekend after Thanksgiving so they could marinate in liquor for a month before the holiday.

When I started going to the Christmas cookie club, I baked cookies instead. Now, I didn’t get complaints from my family about this switch. They all love cookies and look forward to the bounty of twelve dozen home made treats. Fruitcake has become, alas, a joke with a terrible reputation as a hard, tasteless confection filled with indecipherable red and green things. But this year, I missed the fruitcake and wanted to share it with my cookie ladies. So I preserved the the watermelon rind, and then I decided to make amaretto liquor to sprinkle over the cake every week from the time it is baked until the time it is served.

This will be a special Holiday because my entire family will be together. Next year, my son, who lives less than an hour from me, will be accepting a position more than 500 miles away. It will not be so easy for him to stop over for lunch, or drive up with his family so we can walk in the park, watch the ducks and geese in the river, and swing in the playground. Since everyone will be home and it is uncertain when this will happen again, I wanted to return to the early traditions.

So, a week before Thanksgiving, I made the fruitcakes:

Watermelon Rind Fruit Cake

3 cups sifted all-purpose flour 12 ounces white raisins

1 ½ t. Baking powder 6 ½ ounces pecans

½ t. salt 1 cup butter

2 cups drained watermelon pickle shredded 2 cups sugar

6 ounces candied pineapple shredded 5 eggs

7 ounces of your favorite other dried or candied fruit ½ cup amaretto

5 ounce almonds, blanched and coarsely chopped

Marinate the fruits and nuts overnight in some of the liquor.

Preheat oven to 300. Grease 2 9x 12 loaf pans or one bundt cake pan. Or 7 small loaves. I spray well, butter and then spray with oil again. You can also line with wax paper and grease it.

Sift together flour, baking powder, salt. Mix several teaspoons into fruits and nuts.Cream the butter until smooth, adding the sugar gradually. Add the eggs, one at a time, beating well after each. Stir in the flour mixture alternately with the liquor. Mix in fruit and nut mixture.

Transfer batter to pans and press down.Bake two hours. Cool.

Wrap the cakes in cheesecloth and store in an airtight container about a month. Sprinkle weekly with a light shower of liquor.

I bought small bottles to tuck beside each loaf which I filled with the amaretto.

Everything was ready. I was excited.

And then I got sick. Really sick. As sick as I remember ever being. Not sick dangerous. Just sick miserable. Chills. Flushed. Fever of 102. Sore throat. Drippy eyes and nose. Coughs that hurt my ribs.

Well, I went to the party to give out the fruitcakes. I sat in a corner so I couldn’t contaminate anyone. And then left.

A few days later, Marybeth brought over the cookies placing the bag of great and colorful treats in my entryway without bothering me or risking infection.

Another partygoer was unable to attend, ill with the same thing. We’ve been commiserating and sharing home remedies over the phone.

I missed the fun of the party. Passing out the cookies and hearing the stories. The introduction of a new cookie virgin. Dancing. Singing a compromised (and, I understand, slightly dirty) version of the 12 days of Christmas.

Instead, I placed the gaily-wrapped packages of yummies on my table to bring good cheer. When my appetite returned, I ate cookies. Every day I get a little better, by the time the holiday comes I should be well. I made an additional fruitcake for my family to eat soaking in the amaretto. Next year, there will be another cookie party and I’ll see my friends at various events throughout the year. Meanwhile, I witness the bright colors of their packages, and envision my friends’ cheery voices and excitement as I share our bountiful talents.

Enjoy your family and friends everyone!

October 9, 2012

The Old Fashioned Publisher’s Book Tour

Phil Donahue and me!

When A Gift for my Sister hit the stands in May, its marketing was done via the Internet. Traditionally published, Emily Bestler Books, an imprint of Atria, part of the Simon and Schuster publishing empire, sent out promo packets to print and Internet reviewers via email. My appearances were local. Two years ago, when The Christmas Cookie Club launched , I was told I was going on a blog tour. “What’s a blog tour?” I asked. The good news: I could do it at home in my bathrobe, at my own schedule.

They didn’t know I would miss the thrills of the old-fashioned book tour, back when radio and television had local programs, and authors journeyed from city to city promoting books and meeting fans. This was more likely for nonfiction books if the subject was interesting to the TV or listening audience. I was lucky; two of my books were on hot topics. Sex! (Keep the Home Fires Burning: How to have an Affair with your Spouse and Infidelity: a Love Story). I appeared on most of the big time and local TV shows, and many (well over 100) radio shows.

My first appearance was a baptism by fire: Donahue, the national talk show. I had given birth a few months previously, still nursing and still carrying extra baby weight. It was the first time I was away from my baby overnight.

I was both thrilled and terrified. The producer flew me in the night before and housed me in a hotel with the other guests for the next day’s program. I tossed and turned all night answering every question in the world anyone could ask and hoped my baby was sleeping through the night. I added an extra layer of pads in my bra to catch seeping milk, afraid of leaking two wet spots on my dress.

Donahue is magnetically warm, wearing jeans in the green room, prepping us for our appearance. I was made up, powdered to prevent glare. So far, no stains on my dress. I knew there would be no crying baby in the audience. I didn’t even want to think about one.

The audience, prepped to be thrilled that I was there, madly applauded as I walked across the stage and took my seat. Suddenly, I was a celebrity. I glanced down at my dress at every commercial. The pads worked. My fellow panelist’s hands visibly shook throughout the entire hour.

“Don’t be so polite,” Donahue told me. “Interrupt the other panelists when you have something you want to say.” I took his advice. By then, too, the audience asked questions during the breaks. A connection was established and a sense of exhilaration took wing. “I can do this. I am doing this,” I thought. “I’m actually loving it!”

When I watched the show, I realized that TV takes everything down a notch. The shuddering hands and arms of the man sitting next to me were not visible. My excited euphoria was dampened to cheerfulness.

Donahue and Oprah love their audience. You feel it the minute you sit on the set. It’s not about you, or even them. It’s about the people: both the live audience and the unseen millions watching. Since this focus on people is right up my alley, too, I was thoroughly thrilled being on their shows.

The publisher’s publicist books the shows, the hotels, the flights. All I had to do is be away from my kids, reschedule my psychotherapy patients, pack, take a cab to the airport, look as beautiful as possible and sound smart and enthusiastic. Difficult enough!

This is what a day is like: rise early, five-thirty or six, and shower, dress in my new TV appropriate wardrobe, do my hair, grab coffee. I throw everything in my suitcase, police the room, wait for the hotel phone to ring informing me the publisher’s representative is in the lobby. However, on my very first day, the representative is late! I had received an itinerary with all my appointments and am supposed to be picked up at six-thirty for a radio show at seven. It’s five minutes to seven. I panic. I reach the publicist at home; the representative calls and tells me that the radio show is cancelled because the host learned I’d be his competitors guest at eight-fifteen.

Sometimes the host has read the book, or skimmed through a chapter since the book and a publicity packet has been sent from the publisher with a list of suggested questions. If I’m lucky, the show accepts telephone calls from listeners. I love talking to the audience, and having a chance to answer their questions, maybe even help them. It’s why I’m a therapist.

I’m impressed by the radio hosts verbal juggling, accompanied by a finger ballet as they slide tapes or CD’s, push buttons for various music interludes, advertisements, etc. They are enthusiastic about everything, time their speech to the millisecond as they watch the clock then plug in an ad or go to the news. They’re able to BS about any topic if something falls apart.

Then a later morning radio show and drive toward the newspaper. By now it’s 10:00 and on the way, we buy bagels and coffee. We stop at a bookstore; I’m introduced to the owner and sign the available copies of my book. The print interview is a full hour. The interviewer is hilarious and has actually read the book. He gets me chuckling and the photographer snaps a picture of me laughing so hard my mouth is wide open in glee.

Look at those Glasses!

Off for a noon TV show. TV is the apex of these tours; the presumption is more people will be exposed to your book and you can hold it up for them to see the cover. Sometimes there’s an audience, but usually no televised interaction. For a noon TV show, I’d be on for fifteen to thirty minutes.

A little more about TV. I did many of the big TV shows that were popular during that time like Donahue, Sally Jesse Raphael, Sonya Freedman, and Oprah. Did Oprah two times. It helps that they have make up men to make you look spectacular. Somehow, Oprah’s make up man, Michael, gave me a full upper lip, and lectured me that my eyebrows were the frames of my soul. When you walk on the stage, the audience roars with the thrill of you. For a few seconds you almost believe you’re a star. For a moment you are. It’s quite a different sense of yourself than sitting in front of a computer in your bathrobe madly typing. Because of the breaks and the fact the audience gets to ask questions, a real dialogue develops between you and the audience. I looked forward to commercials.

After the TV show are more radio shows. Sometimes these are longer talk shows with call-ins. Each interval between the TV, radio shows are timed to the minute so that I can be driven from radio station to TV to newspaper with a few minutes to spare etc.

Then, we stop for dinner at a local restaurant. I don’t realize how famished I am.

At around seven, I hit a bookstore for a reading. A few people are already nestled in the chairs, coats draped around them. I carry my book well marked with both Post-Its as well as words underlined so I don’t read in a monotone. I meet my audience, my fans, some with personal concerns and sign the books.

Unfortunate things happen: I was supposed to appear on a big national morning TV show. The day before, doing too many push-ups and holding my breath with the strain, a blood vessel ruptured in my eye. My kids told me I looked like Satan. The doctor could do nothing to make my eye white again. I flew into NY for the express purpose of the show. That night, Siamese twins were born: the TV show would try to fit me in, they said. But they never did, and I think my blood eye was part of that. My editor, there for the interview, sags in disappointment, but pretends to be cheery.

In one day, I could do four radio shows, a print interview, two TV shows, and a book reading. I couldn’t do it with out the publisher’s rep driving, prepping me about the hosts, reminding me I need lipstick. It’s hard being ‘on’ fourteen hours a day, smiling, talking intelligently, saying the same things with renewed enthusiasm and novelty, and somehow staying well groomed. I’m drained at the end, tired of answering the same questions with fresh emotion. My cheeks are weary from smiling. I just want to read a good night story to my children and snuggle.

Then I’m off to the airport for the next city. On the plane, behind me, sits the radio jockey from my last show. We’re both going to DC. He’s commuting to his job and going home for a long weekend, missing his wife and children. He asks if I’d be willing to do more radio shows via my phone.

“Sure,” I tell him.

“Hey, I don’t know if I should tell you this, ‘cause it’s not really p.c., but at the end of every week we vote and you won the most attractive woman, well sexiest, of the week.”

“What?” Maybe I was the only woman. I would hope I’d be voted the most interesting.

“This week, it’s actually quite an honor because you beat out the playmate of the year.”

“You’re kidding.”

“The producer thought you were really hot. And interesting.”

And no one could see her sexiness. It was radio, I think.

Ah, Scheherazade. Talking is sexy!

When I arrive home, I drag the garbage to the curb. A book tour is thrilling and exhausting, anxiety provoking and gratifying, but then it’s over. The enormous stress and enormous fun ends. Ordinary life resumes its daily grind, excitement, and sweet domesticity.

Does that kind of tour increase sales more than the blogging/Internet tours that are common today? I don’t know.

In both, the fun for me is hearing from people. Now, your fans can easily reach you, neither they nor you need to go farther than your computer. I read their the various thoughts and feelings about A Gift for my Sister. Whether a tweet, an email message, a question or comment from the live TV audience, it’s gratifying learning the ripples your books make.

This piece first appeared as a guest blog as part of BestSeller’s Sandbox with Terri Guiliano Long. Thank you, Terri for the great fun we had!

September 21, 2012

Hold Fast to Your Dreams – Guest Post by Terri Giuliano Long

“Hold fast to dreams for if dreams die, life is a broken-winged bird that cannot fly.” – Langston Hughes

Hold Fast to Your Dreams - Guest Post by Terri Giuliano Long

Since fall 2010, as I prepared to publish my debut novel, In Leah’s Wake, through the long, tedious marketing process, I learned a lot about myself. I’ve learned what it takes—and how exhilarating it feels—to hold onto your dreams. Early on, a former agent—then selling editing services—told me my book had no merit. “You’ll never sell 500 books,” she assured me, never mind the 5000 I dreamed of selling. That day, and many times along the way, frustrated, exhausted, I considered quitting. But I’d already taken the leap. And I didn’t know if I could do it again.

Despite the odds, the internal demons telling me I was no good, I kept moving forward.

Following a prescribed course is the most probable path to success—and it’s important. Staying on track, being in tune with the culture feels comfortable and safe. But to realize your dreams, sometimes your only option is a leap of faith. That’s hard. It’s scary to move out of your comfort zone, creep into unfamiliar territory. Until you’ve had a chance to reach out and build a community, you’re alone. You’re forced to learn new things—and there’s always a learning curve. You may not be good at everything you try. You may fail. That thought can paralyze you. Yet if you never take a risk, you may never reach your full potential. You’ll never know what you might have accomplished.

For years, I’d hoped to publish a novel, but for a long time I was that broken-winged bird Hughes refers to.

Dave and I had married early, at 18 and 19, and we had four daughters. After graduating college, at 38, I enrolled in a master’s program in creative writing. I wrote the first draft of In Leah’s Wake for my master’s thesis and spent two years revising. My former agent, a lovely person, shopped the book; we had several close calls and received encouragement from some of the most prominent editors in the industry; unfortunately, we received no offers.

I continued to believe in the book and, in 2005, sold it to a small publisher. At last, my dreams would come true! I spent another year revising and countless hours researching markets and media outlets and preparing a marketing plan. Weeks before the launch, unresolvable problems arose and the contract fell through. My attorney suggested self-publishing, but I had no interest. I’d come of age in the traditional world—all my friends were traditionally published—and, like everyone else I know, I stigmatized self-publishers. Self-publishing was for people who couldn’t make it in the traditional world, I thought. If I couldn’t publish traditionally, I wouldn’t publish at all.

For three years, I tried to revise, thinking, if only I can get this right, make it perfect, the novel will find a publisher. But there is no such thing as perfect. Truth: I was writing in circles, floundering. My concerned family, watching me sink increasingly closer to depression, begged me to put the book away, try something new. Reluctantly, I did.

By 2010, the publishing landscape had changed. The stigma was alive, well, and thriving in the mainstream, but traditional publishers had begun to take notice of self-published books. By then, I’d made headway on a new novel, and I saw self-publishing In Leah’s Wake as a step in the process—an audition, if you will. If I could sell 5000 books, a daunting, but impressive feat for a debut novelist, I might, I thought, attract a publisher for my new novel.

Embarrassed of self-publishing, I told no one what I was up to. Not even my parents knew I’d published. Between October and February, I sold about 200 hundred books. In late-February, with sales on the decline, I realized I could either market my book or watch it die—and watch my dreams die along with it! In early March, I started a blog and activated my Twitter account. Within a few weeks, I met Emlyn Chand, founder of Novel Publicity. For two months, we worked on building my platform and we prepared the book for market (revising the description, adding a book club discussion guide, creating a video trailer). In May 2011, I embarked upon my first blog tour.

The bloggers were wonderful – kind, generous, supportive. Social media marketing is not about shameless self-promotion; it’s about forming relationships, connecting with people. I loved this aspect of marketing. Excited about this new prospect, meeting and connecting with bloggers and readers, I put my heart and energy into marketing. In June, I sold 45 books, in July 2000, in August 20,000. Since May 2011, I’ve appeared on hundreds of blogs—and sold over 120,000 books. In Leah’s Wake has won numerous awards, most recently the prestigious Indie Discovery Award, for best literary fiction, and a Global eBook award for best popular fiction. Today, I’m a contributing writer for IndieReader and Her Circle eZine. I’ve appeared on the Jordan Rich national radio show and been interviewed on over a terrific dozen blog talk radio shows. I’ve also been featured in stories in the Newton Tab and Boston Globe and I’ve recently been invited to appear as a guest on an inspirational radio show on Voice of America.

I’m proud of my accomplishments. I’ve worked hard and taken control of my career. I won’t lie: it hasn’t always been easy. Before I could find the confidence to do any of this, I had to stop listening to the inner demons, telling me self-publishing is for losers. I was lucky – Emlyn and I worked well together, and we supported one another. Being part of a supportive community can sustain you. This is something I’ve focused on throughout my tenure as a self-published author. On my blog, we host regular community-oriented events: Indie Week, for instance, celebrated self-publishers and the industry that supports us. Authors, bloggers and industry leaders contributed posts that highlighted their experience and philosophies. Last week, we hosted a charity event to celebrate bloggers and their tireless efforts to support the indie community. I’ve written dozens of articles and news stories about the industry, geared toward informing and educating authors about self-publishing. Building a community pulled me out of myself. I stopped listening to naysayers, focused instead on the tremendously positive energy in the indie community and the exciting changes—many led by self-publishers!—in the evolving publishing industry.

Reaching out, I became an industry leader. People now look to me for help and support. Taking this leadership role reshaped my perception of myself. I used to feel like a loser. Suddenly, I was accomplishing things I never dreamed I’d accomplish – and helping other people. This confidence feeds my soul as well as my work and gives me energy.

Any worthwhile endeavor is hard. Success takes time, energy, and patience. Hold onto your dreams! No matter how frustrated you may be, don’t ever give up: the success you’ve dreamed of may be just around the next corner.

Believe in yourself. Work hard. Hold your head high. You really can make your dreams come true!

Author BIO Terri Giuliano Long is a frequent blog guest, with appearances on hundreds of blogs. She’s written news and feature articles for numerous publications, including the Boston Globe and the Huffington Post. She lives with her family on the East Coast and teaches at Boston College. Her debut novel, In Leah’s Wake, was a Kindle bestseller for more than 6 months. For information, please visit her website: www.tglong.com. Connect with Terri via her Blog, Facebook, or Pinterest. OR tweet her at @tglong

Author BIO Terri Giuliano Long is a frequent blog guest, with appearances on hundreds of blogs. She’s written news and feature articles for numerous publications, including the Boston Globe and the Huffington Post. She lives with her family on the East Coast and teaches at Boston College. Her debut novel, In Leah’s Wake, was a Kindle bestseller for more than 6 months. For information, please visit her website: www.tglong.com. Connect with Terri via her Blog, Facebook, or Pinterest. OR tweet her at @tglong

In Leah’s Wake

WINNER, Global eBook Award, Popular Literature, 2012

WINNER, Indie Discovery Award, Literary Fiction, 2012

Recipient of the CTRR Award for excellence

2011 Book Bundlz Book Pick

Book Bundlz 2011 Favorites, First Place

At the heart of the seemingly perfect Tyler family stands sixteen-year-old Leah. Her proud parents are happily married, successful professionals. Her adoring younger sister is wise and responsible beyond her years. And Leah herself is a talented athlete with a bright collegiate future. But living out her father’s lost dreams, and living up to her sister’s worshipful expectations, is no easy task for a teenager. And when temptation enters her life in the form of drugs, desire, and a dangerously exciting boy, Leah’s world turns on a dime from idyllic to chaotic to nearly tragic.

As Leah’s conflicted emotions take their toll on those she loves—turning them against each other and pushing them to destructive extremes—In Leah’s Wake powerfully explores one of fiction’s most enduring themes: the struggle of teenagers coming of age, and coming to terms with the overwhelming feelings that rule them and the demanding world that challenges them. Terri Giuliano Long’s skillfully styled and insightfully informed debut novel captures the intensely personal tragedies, victories, and revelations each new generation faces during those tumultuous transitional years.

Recipient of multiple awards and honors, In Leah’s Wake is a compelling and satisfying reading experience with important truths to share—by a new author with the voice of a natural storyteller and an unfailingly keen understanding of the human condition…at every age.

Praise for In Leah’s Wake

“An astounding story of a family in transition.” — Tracy Riva, Midwest Reviews

“A powerful and intimate portrait of a family in disarray.” — Margot Livesey, award-winning author of The Flight of Gemma Hardy

“Terri Long’s accomplished first novel takes the reader on a passionate roller-coaster ride through contemporary parenthood and marriage. Sometimes scary, sometimes sad, always tender.” — Susan Straight, National Book Award finalist, author of Take One Candle, Light A Room

“An incredibly strong debut, this book is fantastic on many fronts.” — Naomi Blackburn, top Goodreads reviewer worldwide, Founder Sisterhood of the Traveling Book

“A very moving and, at times, heartbreaking story which will be loved by many, whether they are parents or not.”– A. Rose, Amazon UK, TOP 100 REVIEWER

“Pulled me right along as I continued to make comparisons to my own life.”– Jennifer Donovan, 5 Minutes for Books, Top 50 Book Blog

“A masterpiece of psychological tension and unbearable suspense, a portrait of America in the present day.” — Frederick Lee Brooke, author of Doing Max Vinyl

“Multiple ripples of meaning contribute to the overall intensity of this deeply moving psychological drama.”– Cynthia Harrison, author of The Paris Notebook

September 14, 2012

Invisible Lives: Hunting for Slave Quarters at Montpelier

After the day digging, we’re taken on an archeologist tour of the plantation starting with the slave cemetery. There are at least thirty-five people buried there, probably many more because of the ritual of filling in the depressions formed by the sinking soil so the earth is level. Headstones are large rocks. Several hundred slaves died at Montpelier, but, at this point, their burial places are as invisible as they are. A tree fell over the cemetery, but has not been moved to prevent disturbing sacred resting places. An active group of the descendants of Madison’s enslaved people has organized to advise the archeologists. Do they want to learn the tales their ancestor’s bodies might tell? DNA tests could reveal their origin; forensic work could enable a portrait, and speak of illnesses, beatings, and their nutrition. The progeny will decide if they want to investigate. Then the archeological foundation will need the money.

We visit the original home of Ambrose Madison from 1730’s that burned to the ground. During the civil war, the grounds of the plantation were used as a Confederate war encampment after the army retreated from Gettysburg during the coldest winter on record.

Near it, is the Gilmore cabin. Gilmore had been one of Madison’s slaves. After emancipation, he bought land from Madison’s brother’s grandson and built a house using some the material the Confederate army abandoned. He became a farmer with an orchard and pigs; his wife was a seamstress, and they raised 8 children. Their children occupied the cabin into the 1930’s and remain involved in its archeology and restoration.

Day three: This time I break through the sod. The grass is interspersed with thick clusters of wild onion. My leg resounds with each strike of the spade. Then it’s the usual dirt dirt dirt, but very clayey. Very red. Find a few rocks. Then I unearth a knife or saw blade, handle gone, tip gone.

While we dig and scrape, when we’re not talking about food, Sam tells me about her Master’s thesis, which is, ironically, about food! She worked on Jefferson’s retirement plantation, Poplar Forest, that he inherited from his wife’s family and where the Hemings lived before Monticello. He had over 100 slaves there and it, too, originally grew tobacco. He built a two-bedroom cottage and retreated from his many visitors. Sam is studying pollen and plant materials to learn how the diet of the slaves changed. When the major crop was tobacco, there was a preponderance of wheat in their diets as part of their provisions. But when wheat became the cash crop, there was much less evidence of wheat.

“What was their main grain, then?” I ask.

“Corn had always been important.”

“Imagine what it would be like to be a slave working a field where wheat is all around you, and you can’t pick it and eat it. How hard would that be, especially since you might be hungry.”

“The woods surrounding their homes gave them food and they grew some too— veggies, chickens. This was probably their most important food source, not the provisions their masters gave.”

“They ate wild plants and berries and animals from the forest?”

“Like dandelion greens, opossum, and berries.”

The slaves sometimes sold a chicken or vegetable back to the masters so they could have some cash. Slaves worked from dawn to dusk, six days a week. On Sunday, they tilled their own gardens, built their houses, hunted and gathered in the forest, and sewed their clothes. But we have few slave narratives, some of which are propaganda, of what that life was like for a field slave in the 1820’s. Archaeologists seek a more total understanding from the dirt.

In my daughter’s unit, which is next to ours, they find a quartz point that may be associated with a religious ritual since similar ones were found in hearths. This one is very pretty, with an obvious crystal tip. It’s put in a special bag to be immediately examined, along with a most interesting copper figure that looks like a bear to me, and a handle from an iron. Then she finds a bone that has been split and the marrow sucked out. It is the most intimate sign of the people who lived here.

We work from 7:30 – 3. We have two 15-minute breaks, and one lunch break during which we always eat. We look forward to our snacks breaks: apples and peaches, and crackers, and pistachios and chocolate and yogurt and power bars. We talk about what we’re going to eat while we’re working, describing the sandwich or salad we brought. When we’re screening, we describe cookies, jelly rolls, and brownies, and pies, and Ruben sandwiches and enchiladas. Various favorite beers. Great restaurants within short driving distance. One would think we hadn’t eaten in days instead of a just a few hours ago. Even while we’re eating our highly anticipated lunches, we share what we’re going to make for dinner. I’ve never been with a group that spent so much time talking and fantasizing about food.

Day four is my day in the lab where I’ll see the next step of our artifacts. I need a day off from digging. My left hip and knee are in pain, the kneeling and the hitting the shovel to cut through the sod have taken their toll.

At the lab, we water screen the soil samples. The gallon of dirt is divided into three buckets; water and baking soda are added. Then it is stirred and poured through a ¼ gauge window screen; the clay/dirt is washed away until the water is as pale as weak tea.

The resulting pebbles and charcoal and artifacts are wrapped in very fine mesh screen and left to drip dry. The contents of each bag are sifted through ½ ,1/4,1/8 inch gauge and put in the different bags. Of course, everything is labeled in triplicate. They know what dirt, what carbon, what pebbles came from which unit at which site, and which layer. It took an entire morning for my partner and me to screen 8 gallons of dirt. The seventh one is the sample that Sam and I had dug from our first unit. I find another small triangle of green glass like the one we found in the square.

In the afternoon, I pick through the various pebbles to find artifacts and then put them in artifact bags. So what did I find? Bones. A pig’s tooth. A piece of a shell, perhaps of tremendous value, perhaps of curiosity, perhaps proof of trade so far from the sea. Lots of nails. A small iron hook, charcoal. It’s always fun finding things. The tooth was pretty exciting. And so was the iron hook.

Fifth Day: Sam and I return to our second unit, the knife blade waiting surrounded by the rocks. We clean up the unit, snap its photo, and conserved the knife blade by burying it in soil, wrapping it like a burrito in tin foil, and putting it in a plastic bag. Back to digging. The day at the lab has decreased the soreness in my body. We’re ready for layer B, the second layer of earth. Sam immediately finds some white ceramics, the glaze chipped off in irregular places revealing dark reddish brown clay. Then a shard of green glass appears in the red soil, glass like the bottles that Madison used for wine. More white ceramic. Some with dark blue and light blue rim. Some with dark blue stripes. I sift out a yellow piece with a jagged blue stripe. Sam recognizes the pattern and tells me the blue is the branch of a tree. The colors of the stones and ceramics pulsate in contrast to the dark red earth.

We uncover a bone that has been split, and a pig’s tooth, and a shell. Fragments of quartz and stone flaked away by the Native Americans who lived here before the English and the Africans. Nails caked in the red clayish earth.

All artifacts point to the fact that Madison’s field slaves lived here around 1820 during his presidency and retirement at Montpelier. More than a hundred people worked here for a hundred years, then lived here for a hundred years, but I have not really felt anything from them. I imagined a scenario with the knife, the handle broke off and it was still used. And then the point. And someone- a man? a woman?- threw it away shrugging angrily and thinking this damn thing’s no good for nothing. But an iron knife must have been a prize possession, handled, and saved, and honored as an important utensil.

The bone was split, but it looks like fresh split done by the dirt or our digging rather than 200 years ago. But that’s all I feel. The people are long gone and hidden.

My body is still sore, so I wake up stiff. I say something to my daughter and she says, hers is, too. For hours we are bent over scrapping, lugging buckets of soil. I try to imagine an entire life working from dawn to dusk six days a week. Year after year. Decade after decade. Always sore. Always hungry. And I notice that we too obsess about food while we are on this field. Maybe that is the only way we feel the energy of the people who worked here. Our sore bodies and constant hunger and fascination with food.

The enslaved people who lived here were captives for a long time. Maybe they don’t want to be captured in any way for anyone else’s designs.

My roommate drives me to the field on this last morning and she wonders about the people who lived here, too.

“It seems so unknowable. There’re no buildings at all. When I was digging in the southwest I saw the ruin. This is all invisible,” I say.

“Maybe it’s a metaphor. Slavery is buried underground. And we struggle to find out the basics,” she replies.

Yet, in the 1800’s they were visible. Madison and all his visitors saw his hundred slaves toiling in the wheat field. A few feet from his mansion were the small quarters for families of house slaves; they were a constant presence in his home. It was very visible. A hundred and six black people worked for the wealth and comfort of two.

Both Jefferson and Madison were well aware of the hypocrisy in which they lived. Madison called it the serpent in the Garden of Eden, and Jefferson, who was the progenitor of a biracial family, said in his Notes in the State of Virginia, “It will probably be asked, Why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expence of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.”

But neither of them, in spite of their own beliefs, freed their slaves. Their need for money was primary and slaves provided liquidity. ButJefferson was wrong; black and white Americans are learning to live together, melding into one family. So archaeologists will keep squaring off the field and digging and eventually they, we, will find where the houses were and how big they were and more about what the enslaved people ate, their religious rituals, their treasures. Perhaps we will learn the richness with which they endowed their own lives regardless of the fickle or cruel masters. One day, there will be structures revealing where the 100 + slaves that Madison owned, most of them field slaves, lived. Maybe we’ll even learn from the bodies in the cemetery. American slavery with all its hidden tentacles branching through our country will not be hidden by earth and sod anymore. It is as much a story of our founding as the ‘founding fathers’ and made possible much of our wealth. We will have given voices to the enslaved families, the ancestors of my children and so many of us.

September 12, 2012

Invisible Lives: Hunting for Slave Quarters at Montpelier

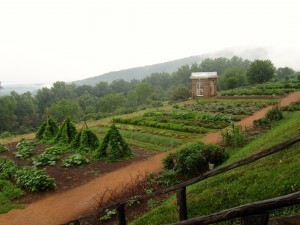

On a sunny, but not too hot morning, the entire team gathers on the Tobacco Field. There are six of us volunteers, five interns who obtain additional field experience before entering graduate school, three field staff who have completed some graduate school in archaeology, and three permanent archaeologists: one in charge of the lab, one a forensic expert, and one in charge of the archaeology department who oversaw the restoration of the mansion itself. We – the interns and volunteers—stay in a house filled with dormitories. Mine has seven beds, but I share only with one woman, an elementary school teacher.

Hundreds of slaves lived and worked on this land since 1720’s, but only a handful of Madisons; during his presidency, there were 2 Madisons and 100 slaves.

The location and sizes of the dwellings of the house slaves and those who worked in the crafts industries (blacksmithing, carpentry, etc.) have been located. Framing had been completed for the dwelling of those who worked a few feet from the mansion. We’re searching for the homes of the field slaves. The site, called the tobacco quarter, abbreviated as TBQ, was the original land that had been cleared for Ambrose Madison (James’ grandfather) by ten slaves and an overseer who spent a decade cutting down the trees, getting rid of the stumps, turning over the soil, and building a house for him. It was the labor of these slaves that allowed Ambrose Madison to claim ownership. It was planted with tobacco until tobacco used up the soil. After 1800, the parcel was used as the dwelling place for the field slaves.

Blue flag markers poke from the ground where metal has been located. This spring, the archeologist thought they had found a dwelling, but, alas, it turned out to be a storage shed for a threshing machine with hand made iron teeth. What is called the South Site is the next most promising place. So far, lots of artifacts have been found, and a barrow pit where people dug out clay to wedge between logs in the dwellings and to prevent the wooden chimneys from catching fire. Afterward, it was used for trash. But no evidence of postholes to support a dwelling, or a hearth has been found.

The site is littered with 5 x5 ft squares that are dug down 6-8 inches. The archeologist block out squares, dig through sod, roots, cobbles of rocks, artifacts and clay soil to find evidence of dwellings. Some show the cobbles of rocks, some only the dark red brown earth, some with hole dug in the middle that is a shovel test.

It’s 7:30 on a Monday morning and I’m partnered up with Sam, one of the staff. She is completing her masters in biological archeology. A baseball cap firmly on her head, her ponytail flows through the space in the back. I’m given a trowel that looks more like an implement for plaster or mudding when dry walling than any gardening tool.

We kneel on kneepads, and scrape away topsoil, struggling against roots. As the day heats and the sun rises, we set up tents to shade us. It is a cooler week in Virginia than it is in Michigan; the arch warnings about the heat and blasting sun have been in vain. We scoop the dirt into dustpans and pour it into buckets, carry them to the screening house, shake the dirt through a ¼ inch mesh hardware cloth, examine the stuff that doesn’t go through the screen. It’s mostly bulbs like a wild onion and pebbles. We do that for 4 hours.

I find a small piece of ceramic, half the size of my pinkie nail, with a bright blue pattern on one side. List it and bag it. The bag lists the site, the day, the square’s designated number, the level of dirt, and Sam’s and my initials.

The next day, we return to the same square, red dirt and white straggles of roots, a hole in the middle where the shovel test was made.

“Let’s clean it out and take its picture,” Sam says. So we scrape it with curving motions of our trowels, scoop the dirt, and get a ladder, a measuring stick to discover depth of the soil, camera, and a chalk board to list the numbers of this particular square, date, the layer. Nothing but red dirt, and a sprig of green grass over the hole.

We start in again. My knees, hips, shoulders and wrists complain as I resume the crouched position. Then, low and behold a rock. A beautiful rock of quartz. One of the cobbles. The people who lived here had small houses, 16X16, that were used primarily for sleeping. All the work was done outside. Stones kept everything from getting too muddy, so there are rocks (not gravel, but cobblestones) placed outside their homes. Stones were also used for the hearth. Within minutes I find a piece of ceramic, white, with a blue flower, and a rim on the other side. And then a few minutes later, another one, and they actually mend together. I’m thrilled. Now these pieces are not very big, maybe a half inch, but a half inch of ceramics from 1820’s is much more exciting than endless red dirt.

Then a perfect triangle of green glass. A few minutes later, a piece of stoneware pottery in a greenish glaze. Now this is big enough to recognize as the curve of the lip of a bowl or pitcher. Almost as big as the palm of my hand.

As the day wears on, kneeling on kneepads, bent over a 5 foot square of red dirt, we uncover more cobbles, eleven more pieces of the stoneware ceramic, and more glass. Each find is a treasure unearthed from the dirt, as though a message from the past. We find nails, bent broken, and burned. Enslaved people were responsible for building their own homes, they were given nails handmade in the craft section. They were given flax or cotton to weave and sew their own clothes.

So we scrape, and sift, and there are rocks, and weeds. More glass, more ceramics, scads of nails. We take it down another layer. Then there’s a big discussion whether we should continue. The pattern of the cobbles is used to learn where the people lived. How large their houses, how many, what they ate, how many people lived in each house, how they were made, etc. The bits of ceramics and glass only offer a small part of the picture and aren’t what they seem. For example, a beautiful but broken dish. Was it given to the slave as a present because it was only slightly chipped and then later broken? Or did the slave break it, and then try to hide the accident from the mistress? A secret wine bottle stash in the kitchen – was it a way to hide a bottle of wine and then pick it up on the way home? It was filled with layers of ashes and dirt. Maybe it was part of a ritual ceremony? No one knows.

At the end of the day we put a gallon of unscreened soil in a special bag and label it with the site, and square name, date, level of soil, and our initials.

Tomorrow I find out if we continue with that square or if we open up a new one. I am attached to continuing in this one, hunting for more broken bits, but I may never see the artifacts I found again, and the earth may not be worked to discover if the rest of the pieces of the stoneware bowl are uncovered. Maybe we will dig finding additional artifacts. Maybe we will open up the earth in another square to see what secrets treasures the green sod hides.

September 10, 2012

Invisible Lives: Hunting for Slave Quarters at Montpelier

Part III: James Madison- A 2012 look at a Founding Father

Archeology played a crucial role in the restoration of the mansion of Montpelier now returned to its glory when Madison was president. Domestic slaves lived near the mansion; archeologists uncovered the size and form of their dwelling close to a kitchen, as well as two smoke houses. Frames waiting for funds to fully restore them illustrate their size and location. Two enslaved families lived in a duplex that was 16 X 20.

James Madison studied and dreamed of democracy and equality. Our marvelous constitution with its intricate checks and balances has preserved our democracy and our self-government. But it had a flaw and the flaw was slavery. As he lay dying, he wrote, in his open letter to my country, “Don’t let the serpent destroy the Garden of Eden” and the serpent was slavery.

James Madison and Thomas Jefferson were best friends and colleagues, their lives intertwined in striking ways. They both switched from tobacco to wheat as their cash crop, which was true for most of the other planters. Madison’s wife, Dolley, entertained with Jefferson when he was President. They had difficult family lives and both died penniless. They chose the same blue and white Chinese imported porcelain as dinnerware.

In this important election year, a year in which much of the constitution and our founding fathers’ words and thoughts are quoted, both the conflicts in their lives as well as their ideas have wisdom for our modern times. I did not anticipate, nor was it one of my motives, to be absorbed in the life, thought or ideology of Madison and Jefferson. There was no way that I could have anticipated that their ideology would be adored anew. I had come to investigate the life of their slaves; surely not their most proud moments. Yet, I was immersed in their passion for freedom, equality, and their own awareness of irony before they were reclaimed and reinterpreted in the heat of the current political struggle. History is alive and relevant to our time, especially, Madison’s passion for separation of church and state as politicians use religious values as justification for laws and positions.

As a delegate to the Virginia Convention in 1776, Madison suggested profound changes proclaiming the right, rather than merely tolerance, to the free exercise of religion. He worked with Jefferson to disestablish the Anglican Church from the state. Religious belief was “precedent, both in order of time and in degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society.” Thus, he placed freedom of conscience prior to and superior to all other rights, and gave it the strongest political foundation possible including acceptance of liberty of conscience for people who are atheists.

Separation of church and state was guaranteed by the first amendment of our constitution. More than any other person, Madison is responsible for the religious freedom that is so crucial to our values. We assume, and politicians proclaim, we are a Christian country. Madison and Jefferson worked hard to form a state that was not tied to a religion. They did not want the state to control religion, or religion to control the state. We are not a Christian country; rather we are a country where most of its people are Christian of many different denominations and beliefs.

James Madison was a complete nerd. Only 5’4”, frail with a whispery voice, he loved books and completed Princeton in two years. He became involved in the burgeoning freedom movement, took his concerns back home to Virginia and spent the next few years working for religious freedom with Thomas Jefferson. Aware of the weakness in the 1781 articles of Confederation, Madison devoted several years studying every recorded attempt at self-government, rule by the people rather than a monarch. Thomas Jefferson shipped him books from Paris and Madison’s fluency in several languages allowed him to read in Greek and Latin and French and Hebrew. Madison pondered: Why had all the past democracies failed? How could the interests of individuals, states, and national authority be balanced? And he came up with our Constitution sitting in his library in Montpelier with a view of his plantation, and beyond that, the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Madison led the Constitutional Convention and, in spite of his tiny voice, his big ideas and persuasive arguments won the convention to many of his ideas.

Ironically, Madison had a slave, Billey, with him. Billey was privy to the discussions and questioned Madison. Madison realized Billey couldn’t return to the plantation because he might spread the ideas of equality and freedom to the other slaves. “I do not expect to get near the worth of him; but cannot think of punishing him by transportation (further south) merely for coveting that liberty for which we have paid the price of so much blood, and have proclaimed so often to be the right, and worthy the pursuit of every human being.” So Madison sold him to someone from Philadelphia where slavery lasted only seven years. This incident elucidates Madison’s own awareness of the inherent hypocrisy, but money and power trumped his own ideals.

Madison didn’t get married until he was 43, adopting Dolley’s son (who was a gambler and alcoholic and ended up driving him to bankruptcy and both Madison and Dolley into poverty so she had to sell Montpelier). They never had any children. Madison went on to become President for two terms and then retired to Montpelier at 66, founding, with Jefferson, the University of Virginia. He died at 85, his slave, Paul Jennings, by his side.

It was Madison’s grandfather who sent ten slaves there to clear the land that became the plantation. Then, if you cleared land and built a house, you owned the property. The field they cleared was planted with tobacco. Madison’s grandfather was poisoned (a slave was hung for his murder) and his wife managed the thriving tobacco plantation until her son was able to take it over. James Madison was the eldest of his eleven children.

When the tobacco boom ended, the field became the space for the homes of those slaves who worked wheat fields. This is the field where we would dig.

September 8, 2012

Invisible Lives: Hunting for Slave Quarters at Montpelier

We drive south from Michigan on a sunny day, angling through the hills of Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Beside us are cliffs of shale, signaling the coal that once was there, mountaintops carved away, their heads chopped off and their guts—the coal—shipped, sometimes on trains driven by my son bound for China. As this crossroads election heats up, angry signs are plastered at the regulations curtailing the destruction of the mountains and rivers for the gold of coal. What is left are trees curtained with kudzu, and skirted with dense ferns. To capture the America away from the highway, we drive back roads, noting the picturesque towns, some with old-fashioned buildings of stone, or artfully patterned bricks, flowery hanging planters. But poverty. White rural poverty. And signs about coal everywhere.

We start down Skyline drive, a curvy road through the Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. Off to the right, at the edge of the mountain lays the plain of rich green squared off crops and farms, ponds, lakes. We hike on the ridge, climb a rock pile and reach the highest summit of the Appalachian trail to overlook the Piedmont. Beyond the ancient hills are the double blue ridges of mountains ringed with clouds.

“Look at this, this rich, magnificent land. This is where they dreamed up the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights. Here. This is the land they fought for, wanted the freedom to have and own,” my daughter says. I do not consider until then that we are voyaging to the place where America democracy and freedoms were envisioned. Or that this land shaped their desires and our destinies. The richness of the land was not able to be harvested, not able to be turned into cash crops without slaves. They were necessary for the massive growing of tobacco, a labor-intensive crop. Tobacco wore out the soil almost as quickly as it did its laborers, testament to greed of mankind.

On the way down the mountains, a baby black bear walks beside the road. An eagle soars next to us.

The next day, we visit Thomas Jefferson’s mansion, Monticello. Jefferson’s relentless curiosity, constant inventions as well as his timeless artistic sensibility are apparent everywhere. Indian history robes from the plains, European art, bones of mastodons, crazy clocks that tell the time and the day of the week by intricate weights, a set of French doors that both close when one closes, a polygraph that automatically copies what he writes. His bed is between his library and his writing room; from it, he can he gaze through a series of French doors into the garden. He figured out how to have indoor privies and improved plants with his knowledge of botany. All this. And of course the Declaration of Independence and his supreme belief in science and rationality as a way to make life better. All men are created equal and have the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. In his day, all men meant white males who owned property.

Jefferson lived in one of the more bizarre, and difficult family situations, indicative of the complex relations slavery engendered. He inherited his father-in-law’s slaves and plantation. Included in this were the Hemings family and several children including the infant, Sally, who were his wife’s half siblings. His wife died. When Jefferson was in Paris, Sally came to take care of his daughter, Martha. Sally became pregnant and gave birth to 6 children fathered by Thomas Jefferson over the next thirteen years; two died before reaching adulthood. The tour of the house and museum reveal scads of stories about the Hemings family who worked in the house, his blacksmith and furniture crafts, and helped Jefferson build and design the mansion, and gardens. The stories of their lives could—and have—been retold as novels.

When Jefferson retired, he wanted his daughter and her eleven children to live with him and cloistered the dining room, inventing a doubled-doored closet so that no servants would interrupt the conversation. Except for two eight and ten-year-old slaves who happened to be Hemings, related to the people they served. Thus both Jefferson’s families were around him, his white family as well as his slave family. I wonder if Jefferson felt smug about the irony in this as if he were getting away with something and arrogant in his power, or if he were merely exposing his slave children to the discussions of ideas and books. And I wonder what Jefferson’s slave family thought about their free relatives.

It’s impossible to know what Jefferson felt about Sally or their four children. Or to presume how she felt about Jefferson: was she doing what she was forced to do, what was expected of her, to guarantee her children the easier life of house slaves? Did she love him? He freed his four living children with Sally; the daughters moved into the white world. Jefferson’s sons ended up taking care of Sally and, after she died, moved to Ohio. One of his grandsons, endowed with Jefferson’s red hair and grey eyes, was a Colonel in the Union army.

Jefferson died penniless. He had inherited debt along with the slaves from his father-in-law and tobacco as a cash crop was no longer profitable.

Though he believed in the slaves should be free, Jefferson feared for the safety of whites at the mercy of former slaves who had, in his words, been subjected to “unremitting despotism” and “degrading submissions.” I wonder if those degrading submissions were Sally’s.

His daughter sold his slaves to pay debts. Ultimately, the slaves, even those who were related to her, were property, a way to get cash when necessary.

September 6, 2012

Invisible Lives: Hunting for Slave Quarters at Montpelier

American racial ideology is as original an invention of the Founders as is the United States itself. Those holding liberty to be inalienable and holding Afro-Americans as slaves were bound to end by holding race to be a self-evident truth. Thus we ought to begin by restoring to race—that is, the American version of race—its proper history…Barbara Jeanne Fields

Part I: Warnings Before I leave

When I tell my friends and family that I’m going on an archeological dig in slave quarters on a tobacco field that is part of James Madison plantation, I’m met with a wide variety of reactions. Several friends narrow their eyes and say, “Virginia? In August? You know how hot it will be, right?”

My hairdresser offers tips on greasing my hair with jojoba or olive oil and turning the occasion into a heat treatment instead of risking hair torture by the sun. Other people nod slowly or wave a hand and comment, “That’s something you would really like” with the clear understanding that they would never sign up for hard labor, in the heat, and dirt, but it fit me.

A friend whose mother had worked on a tobacco field cautions, “My mom had to squish the worms between her fingers. There were poisonous snakes, too. But she was terrified of the worms.”

Another, who’s an artist, becomes very quiet, and concentrates on her fork poking her salad.

“Whatcha thinking?” I ask.

She raises serious brown eyes, “You might be disturbing old souls. And pick up gloom from their tragedy. Imagine the horror.”

“I hope to give a voice to their lives. So we’re reminded again. The issues resulting from slavery have not been erased from our country. Who knows, maybe I’ll even be inspired with a new character.”

“It’s like visiting the holocaust museum or Auschwitz. You’re inviting nightmares, you expose yourselves to torture, death. It might blanket you for months.”

Her reaction is most similar to a friend who is in prison in California. He becomes very quiet, then says, “People contribute a degree of compassion to slave owners that doesn’t exist. You can’t work someone to death and have a degree of compassion. This—prison—is a cakewalk compared of how slaves were treated. It’s hard being in handcuffs but that’s nothing compared to a five pound shackle around your neck. This is a result of a bad decision and life mistake I made. There are no slaves who made a bad decision and ended up in America.” He continues, “When you’re walking through those tobacco fields remember that a couple hundred years ago those tobacco fields were fertilized by human lives. Because the whites captured a people they didn’t respect and forced them to do work they couldn’t or wouldn’t do. They decimated a group of people and they’re scared there will be 400 years of payback.

“This country was built on the back of backs of slaves. Don’t excuse the slaveholders.”

The husband of one of my dear cookie club friends says, “Well you’re going to learn a lot about the constitution and history. Can’t wait to hear all about it.”

Yes, it is through history that I learned about this program. My daughter and her fiancé are both American historians, his area of concentration is the Revolutionary period, my daughter is passionate about modern American history, 1965-1985. They were at Monticello, Jefferson’s plantation, and took the thirty mile trip to James Madison’s plantation where they stumbled across the archeological lab. Excited, they call me up and suggest that the three of us go. “August will be when they’re finding the most important stuff,” my daughter promises. “This will be sooo exciting.” (She speaks like me) “We thought it would be a great trip for us to do together.”

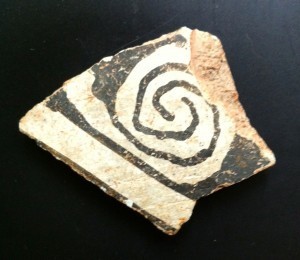

They know me and my interest in archeology, which comes from the love of Egyptology and having been on several digs in the American southwest. There I dug in a midden—a garbage pit—beside the ruin of crumbling adobe bricks. I had a sense of the people who lived there, the walls they walked between, the doors they entered, the kiva where they performed rituals and prayers. My most exciting find was a potshard with a fingerprint. I placed my finger over the small print, the whirls still embossed by the clay. I imagined the woman who made the bowl sitting in the same spot, seeing the same desert, the far away mesa, the unbelievably blue sky, and felt her presence, this woman from a thousand years ago. Before they knew that the white man and white diseases existed.

But it isn’t only an abstract love of archaeology that drives me. As many of my readers know, we are a biracial family. Some of my daughter’s ancestors were slaves in the American south. We are seeking understanding of their lives. And a closeness with the least understood or examined group during the formation of our country.

We sign up, and the archeology department sends a forest green tee shirt, and two books: one on James Madison and one on the archeology program at Montpelier.

Of course I don’t read them. I ready myself for the launch of A Gift for My Sister, my second novel which has as a major theme the formation and acceptance of a biracial family, and a trip to Croatia where I give a copy of the Croatian translation of Christmas Cookie Club to a family there. Meanwhile, I fantasize about what I’ll find on a tobacco field in Virginia in the heat of August.

This is the first of a five part series on an Archeological dig at James Madison’s Plantation, Montpelier.

August 16, 2012

Spaghetti Squash and Fresh Tomato Sauce

Here’s a fresh, easy to make, low cal, low fat dinner that will particularly appeal to those who like to improvise their recipes. The key element is the tomatoes you chose. Pick flavorful ones: heirloom, the new dry farmed , cherry or a combination. My farmer’s market still has good tomatoes, but this might be the last week. This is how you make the dish:

Sauté onions (one large one, chopped) and three or four cloves of garlic, chopped, in 1 T. of olive oil.

Add a chopped green pepper (and jalapeno if you like it spicy. )

Add sliced mushrooms.

Let this mixture cook until everything is soft.

Now add three or four large tomatoes. You don’t need to peel them, just chop them up and throw them in.

Add salt and pepper to taste. And fresh basil.

Cover and let simmer for five or ten minutes.

Meanwhile, take a whole spaghetti squash, pierce it , and microwave it for five minutes. Turn it over and microwave for another 4minutes. Check to see if it’s slightly soft. Let it cool for 5 minutes. Then cut it in half, scrape out the seeds, and use a fork to ‘comb’ strands. It’s a great low cal, low carb substitute for pasta.

Now, taste your sauce. What does it need more of? Wine? Red pepper? You can add ground meat, or Italian sausage, or Soy burger if you want.

Put the squash on plates, cover with sauce, sprinkle parmesan cheese on top.

Enjoy!