Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 70

June 8, 2014

The importance of fairy tales by Abie Longstaff

On the 5th June, Richard Dawkins caused a bit of a fuss by making a number of comments about fairy tales. In an interview with Richard Bacon about fairy tales and fantasy, Dawkins posed the question: “Is it a good idea to go along with the fantasies of childhood?” and added: "I think it's rather pernicious to inculcate into a child a view of the world which includes supernaturalism." http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p020dvd7

This provoked a media storm, resulting in a number of articles misrepresenting his comments such as: ‘Fairy tales and believing in Father Christmas could cause children harm. This is according to controversial biologist Richard Dawkins who warned an audience at the Cheltenham Science Festival about the dangers of make-believe.’ (The Daily Mail) ‘Reading fairy stories to children is harmful, says Richard Dawkins’ (The Telegraph)

Dawkins later clarified his position on fairy tales in an interview with the Guardian, saying "What I actually think is that fairy tales can be wonderful. They are part of childhood, they are stretching the imagination of children...about ten years ago I raised the question whether a diet of supernatural magic spells might possibly have a detrimental effect on a child's critical thinking. I genuinely don't know the answer to that, and what I repeated at Cheltenham is that I think it is a very interesting question. I actually think there might be a positive benefit in fairy tales for a child's critical thinking" (http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/jun/05/richard-dawkins-fairytales-not-harmful)

Following all this kerfuffle, Channel 5 news invited me to come on and discuss the importance of reading fairy tales to children.

It was one of those days when your opportunity comes at the worst possible time: my kids had been up in the night with colds, I hadn’t washed my hair in days, I was on my way to my day job where I had a meeting with the Treasury about the future of policing, my phone wasn’t fully charged, I had no make-up on and, worst of all, I was wearing green (a big no-no in TV world). So I rushed around like a mad thing stressing about it all.

My segment was really short and there was so much I wanted to say that I couldn’t fit everything in!

My 3 minutes of fame is here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSWz_Jk-Drw

I wanted to say:

Fairy tales deal with difficult and dark themes. They provide a vehicle for children to explore those themes within the safe space of a familiar tale, with fantasy characters. They help children come to terms with real fears and they encourage empathy for others with less fortunate lives.

They are not particularly about magic. They are stories of human behaviour – of struggle, of survival, of hope. They deal with the enduring concepts of love and friendship and the triumph of good over evil. They carry morals (love someone for who they are) as well as warnings (don’t talk to strangers).

As adults we read and watch a lot of fantasy, from genre shows like Games of Thrones, to action films like James Bond. We don’t constantly need to remind adults that 007 couldn’t really have jumped out of a plane and opened his parachute the second before a plane exploded, or that The Matrix doesn’t comply with the laws of physics. As adults we know that fantasy is escapism and fun. And we can distinguish easily between fact and fiction. We should accord children that same level of intelligence – we shouldn’t patronise them. I don’t know a single child who really believes that a frog could turn into a prince if you kissed it! Children understand allegory and they recognise the moral portrayed in the story.

I believe that, for the most part, we should let children choose what they want to read and what stories they want to listen to. There is a reason fairy tales have lasted so many years and are still being made into blockbuster films in 2014 – they are exciting and adventurous and they deal with issues that are still relevant today.

And as for me: I’ve learned that I need to carry a phone charger and a little make-up bag with me everywhere I go!

P.S. Philip Pullman has written a much better article than mine on Dawkins and Fairy tales here: http://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2014/06/imaginary-friends-philip-pullman-fairy-tales

Abie's latest book, The Fairytale Hairdresser and Snow White, is in book shops now.

Published on June 08, 2014 23:00

June 3, 2014

How much to charge for fee-only picture book text

Moira Butterfield

Before you read this, I just want to point out that I’m not intending to depress you. I’m out to offer some sensible tips. All the examples mentioned below have happened to me in the past, so learn from my mistakes. A number of major mass-market UK publishers have recently declared their intention of moving ‘upmarket’. They are producing picture book material which they hope will compete with the picture books published by more traditional publishers, possibly in the same outlets. These mass-market publishers are big players internationally, selling rights to other similar publishers around the world. If you’re reading this in, for example, the US or Australia, you will see the material I’m talking about in due course. These publishers are now aiming to produce ‘upmarket’ picture books. I’ve put that word in inverted commas because, although these picture books are structured in the classical way, and are deliberately designed to compete with what might be described as ‘classy’ picture books, the economics behind them are not the same. Mass-market publishing companies do not pay royalties. They want to own content so they can exploit it financially in any way they wish to make as much revenue as possible and- importantly for them - have an asset that they could perhaps sell at a future date. Owning content is the 21st century buzz phrase of media conglomerates. What does this mean for picture book authors? I’m not going to say whether these fee-only books are good or bad, and I can’t predict how they will affect sales of more traditionally-modelled picture books. They are a lot cheaper and it’s unlikely the public will differentiate in a shop between the two. But that’s not my thread here. It’s up to the traditional publishers to defend their market sector, I guess. What I want to say is this. If you are asked to provide a picture book text and you are offered a fee- only deal - and you want to consider it - be prepared. Be aware and do it with your eyes open. (I know that there will be people out there who will howl at the idea of doing fee-only work, and congratulations to them if they can make a living and pay all their bills on royalty projects alone. This is advice for those who might wish to say yes.)Why would you say yes? Well, you might be a new author or illustrator who wants to get into print. This may be a valid way for you to do it. Assume, however, that you won’t be informed of sales figures and you won’t be publicized as a star author. The publisher owns the content, not you, and they’re not interested in paying anything extra for a ‘star author’. Follow-up titles are not guaranteed, and if they do turn up it’s possible that someone else could be asked to do the text. In other words, don’t offer a fee-only picture book publisher your most cherished ideas. I don’t mean do a shoddy job. I mean don’t give them your prize idea. The one you’ve been working on for two years. The one you think is brilliant. The same rules apply if you are an experienced author with a track record, but you need the income. No problem there, but don’t hand over your most precious ideas. You might, in this case, want to consider working under a pseudonym. You’re not going to get paid extra for your name. On the other hand it could be valuable for you to have your name visible on book covers all over the place – supermarkets, for instance. That judgement is up to you. If you have an agent, chat to them about it. You might get a great editor, but you may instead find yourself dealing with a very inexperienced and heavily-overworked young editor (many older more experienced editors having been made redundant from all sorts of publishers during the recession, to save on wage bills). In the case of a fee-only job this situation could have consequences. That young editor might start messing up your text and you don’t actually have any rights to say ‘no’ to changes. However, you can point out, in a positive and helpful way, why the suggested changes might be bad. It’s possible that nobody else is going to be helping that young editor learn their work. When you agree to the job, make it clear that you want to discuss changes made (that you want to help and you will not slow down the schedule, which is likely be very tight). You might also want to point out if you have built a rhythm into the text (it sounds crazy, but believe me, very inexperienced editors may not notice). You may be asked to do publicity. You’re not going to generate any extra royalty money from the effort, but you are going to raise your profile by doing so. This is a valid reason for agreeing, but make sure you get fair expenses (see Society of Author rates). The fee….the big question. What is fair? Well, publishers should not pay board book rates for picture books. By that I mean the rates they might pay for a 4 or 5-spread mini story or learning text (around about £300-£500, say, but of course it varies). Picture books, as we know, are more complicated delicate mechanisms and should be properly valued. We can do that as best we can collectively but, having said that, we are up against the ‘I fancy a go at writing’ brigade. A leading UK art agency has done a deal with one of the publishers I’m thinking about, offering them the picture book ideas of all their illustrators. In the deal, the text itself hasn’t been given any value, basically. Presumably the editors are going to try to bash the ideas into shape. Yup, sorry, I did say I wasn’t going to depress you….But there’s nothing we can do about that sort of deal. All we can do is value our work as best we can. It’s up to you to say yes or no to a fee, and it will depend on your individual circumstances. But if you want to say ‘yes’, don’t agree to a board book rate. These publishers are likely to be doing costings on big sales figures. You could even ask your editor what the projected sales figures are before you say yes. Why not? They will have a figures spreadsheet with the information on it. I don’t see why you shouldn’t know before you agree to your fee. As a ballpark figure I’d make a suggestion of £1500. That seems eminently reasonable. You could even go in higher and see what happens. Perhaps you’d be prepared to take a tad less. But if the publisher scoffs and offers you a board book fee my advice would be to say no.

www.moirabutterfield.com

@moiraworld

Before you read this, I just want to point out that I’m not intending to depress you. I’m out to offer some sensible tips. All the examples mentioned below have happened to me in the past, so learn from my mistakes. A number of major mass-market UK publishers have recently declared their intention of moving ‘upmarket’. They are producing picture book material which they hope will compete with the picture books published by more traditional publishers, possibly in the same outlets. These mass-market publishers are big players internationally, selling rights to other similar publishers around the world. If you’re reading this in, for example, the US or Australia, you will see the material I’m talking about in due course. These publishers are now aiming to produce ‘upmarket’ picture books. I’ve put that word in inverted commas because, although these picture books are structured in the classical way, and are deliberately designed to compete with what might be described as ‘classy’ picture books, the economics behind them are not the same. Mass-market publishing companies do not pay royalties. They want to own content so they can exploit it financially in any way they wish to make as much revenue as possible and- importantly for them - have an asset that they could perhaps sell at a future date. Owning content is the 21st century buzz phrase of media conglomerates. What does this mean for picture book authors? I’m not going to say whether these fee-only books are good or bad, and I can’t predict how they will affect sales of more traditionally-modelled picture books. They are a lot cheaper and it’s unlikely the public will differentiate in a shop between the two. But that’s not my thread here. It’s up to the traditional publishers to defend their market sector, I guess. What I want to say is this. If you are asked to provide a picture book text and you are offered a fee- only deal - and you want to consider it - be prepared. Be aware and do it with your eyes open. (I know that there will be people out there who will howl at the idea of doing fee-only work, and congratulations to them if they can make a living and pay all their bills on royalty projects alone. This is advice for those who might wish to say yes.)Why would you say yes? Well, you might be a new author or illustrator who wants to get into print. This may be a valid way for you to do it. Assume, however, that you won’t be informed of sales figures and you won’t be publicized as a star author. The publisher owns the content, not you, and they’re not interested in paying anything extra for a ‘star author’. Follow-up titles are not guaranteed, and if they do turn up it’s possible that someone else could be asked to do the text. In other words, don’t offer a fee-only picture book publisher your most cherished ideas. I don’t mean do a shoddy job. I mean don’t give them your prize idea. The one you’ve been working on for two years. The one you think is brilliant. The same rules apply if you are an experienced author with a track record, but you need the income. No problem there, but don’t hand over your most precious ideas. You might, in this case, want to consider working under a pseudonym. You’re not going to get paid extra for your name. On the other hand it could be valuable for you to have your name visible on book covers all over the place – supermarkets, for instance. That judgement is up to you. If you have an agent, chat to them about it. You might get a great editor, but you may instead find yourself dealing with a very inexperienced and heavily-overworked young editor (many older more experienced editors having been made redundant from all sorts of publishers during the recession, to save on wage bills). In the case of a fee-only job this situation could have consequences. That young editor might start messing up your text and you don’t actually have any rights to say ‘no’ to changes. However, you can point out, in a positive and helpful way, why the suggested changes might be bad. It’s possible that nobody else is going to be helping that young editor learn their work. When you agree to the job, make it clear that you want to discuss changes made (that you want to help and you will not slow down the schedule, which is likely be very tight). You might also want to point out if you have built a rhythm into the text (it sounds crazy, but believe me, very inexperienced editors may not notice). You may be asked to do publicity. You’re not going to generate any extra royalty money from the effort, but you are going to raise your profile by doing so. This is a valid reason for agreeing, but make sure you get fair expenses (see Society of Author rates). The fee….the big question. What is fair? Well, publishers should not pay board book rates for picture books. By that I mean the rates they might pay for a 4 or 5-spread mini story or learning text (around about £300-£500, say, but of course it varies). Picture books, as we know, are more complicated delicate mechanisms and should be properly valued. We can do that as best we can collectively but, having said that, we are up against the ‘I fancy a go at writing’ brigade. A leading UK art agency has done a deal with one of the publishers I’m thinking about, offering them the picture book ideas of all their illustrators. In the deal, the text itself hasn’t been given any value, basically. Presumably the editors are going to try to bash the ideas into shape. Yup, sorry, I did say I wasn’t going to depress you….But there’s nothing we can do about that sort of deal. All we can do is value our work as best we can. It’s up to you to say yes or no to a fee, and it will depend on your individual circumstances. But if you want to say ‘yes’, don’t agree to a board book rate. These publishers are likely to be doing costings on big sales figures. You could even ask your editor what the projected sales figures are before you say yes. Why not? They will have a figures spreadsheet with the information on it. I don’t see why you shouldn’t know before you agree to your fee. As a ballpark figure I’d make a suggestion of £1500. That seems eminently reasonable. You could even go in higher and see what happens. Perhaps you’d be prepared to take a tad less. But if the publisher scoffs and offers you a board book fee my advice would be to say no.

www.moirabutterfield.com

@moiraworld

Published on June 03, 2014 22:00

May 29, 2014

The Rather Perplexing Picture Book Quiz, by Malachy Doyle

I’ve been rootling through my picture book collection and come up with twenty seven questions to provoke and perplex you. Some are easy; some are, hopefully, stinkers. A prize for whoever gets the most right. (The prize is me saying WELL DONE YOU!)

Put your answers in the comments section and I shall reply with how many are correct. I won’t say which ones, or that’ll make it too easy for the people coming after. But as the number rises, feel free to keep trying till we get as close to twenty seven as possible. Have fun!

1.Who am I, and what are my two grannies called?

2. Name Fungus the Bogeyman’s wife and son.

3. Who did the Tiger come to have tea with?

4. Who's this handsome man?

5. What’s hidden in each picture of Masquerade?

6. What two colours does Wally always wear?

7. And who do we have here?

8. What's the sweetshop called in The Giraffe and the Pelly and Me?

9. Where did Yertle the Turtle live?

10. Name Olivia’s little brother, who's always copying her.

11. Who's this Little White Rabbit with Wings?

12. Who does Handa go to visit?

13. What is the Paper Bag Princess's real name?

14. What did someone dream up to stop cavemen looking rude?

15. Who falls through the dark and into the light of the night kitchen?

16. By what name is Prince Amir of Kinjan better known?

17. How did Rabbit save a little bit of winter for Hedgehog?

18. Name Orlando's three kittens.

19. How did Bella get Dogger back?

20. In what village did The Little Train and The Little Fire Engine live?

21. What did Big Mamma say when she made the world?

22. Name Captain Slaughterboard’s pirate ship?

23. Who is this car? And what's its more formal name?

24. Green Frog, Green Frog, what do you see?

25. What should you not do if you want to walk in peace on a Summery Saturday Morning?

26. How does Big Bear eventually get Little Bear to sleep?

27. and finally... what are the only two words other than HUG?

27. and finally... what are the only two words other than HUG?

Published on May 29, 2014 23:44

May 24, 2014

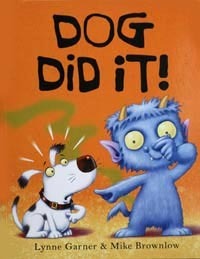

Do The Words Just Come? - Lynne Garner

Uncle Albert during his national serviceA few days ago I was on the phone to my Uncle Albert - all my close friends have heard of Uncle Albert. He's an ace with wood (he was a cabinet maker in a former life and the queen has apparently made him a cup of tea - although in truth I think she got someone else to make it), has a great sense of humour and sometimes asks some very probing questions. Anyway we were discussing the weather, what the dog was up to and how my writing was going. Then he came out with "do the words just come?" I asked him what he meant. "Well do the words just come as you write or do you plan everything first?"

Uncle Albert during his national serviceA few days ago I was on the phone to my Uncle Albert - all my close friends have heard of Uncle Albert. He's an ace with wood (he was a cabinet maker in a former life and the queen has apparently made him a cup of tea - although in truth I think she got someone else to make it), has a great sense of humour and sometimes asks some very probing questions. Anyway we were discussing the weather, what the dog was up to and how my writing was going. Then he came out with "do the words just come?" I asked him what he meant. "Well do the words just come as you write or do you plan everything first?"After a few moments of thinking (I only do that thinking stuff in short bursts. I don't want to burn myself out with too much of it) I realised it depends on what words he was asking about. By that I mean dialogue or action. I never used to be a planner but a few years ago I attended a couple of weekend writing retreats organised by the Scattered Authors Society and from that time forward I started to plan (although very loosely).

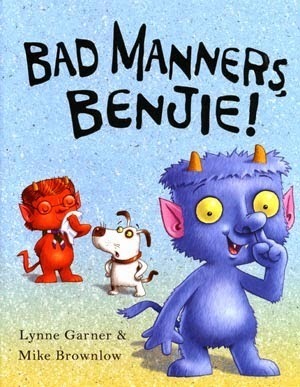

However after looking at my current work in progress and the plan for my last published picture book (Bad Manners Benjie!) I discovered I plan the action. I know what's going to happen and when but the conversation I leave to the characters to write.

However after looking at my current work in progress and the plan for my last published picture book (Bad Manners Benjie!) I discovered I plan the action. I know what's going to happen and when but the conversation I leave to the characters to write.For example for my latest work in progress (a collection of shorts stories rather than a picture book) I have the following scribbled in a book (I do my writing directly onto my laptop but my ideas and planning are done in one of my many note books. I've a growing collection of them with some of the really lovely ones still empty, as I just haven't had the heart to write in them yet). Sorry I digress. These are the notes for one of my short stories:

Character A is out for an evening stroll when he overhears a conversation between characters B, C and DThey are planning revenge for a trick he'd played on them the day before.Characters B, C and D agree to meet in a few days once they've had time to come up with some ideas. At this time they'll agree which is the best idea and start to plan their revenge. Character A decides to break into homes of characters B, C and D to see if he can discover what their ideas are.etc. etc. etc. As you can see I know what is going to happen but I haven't a clue what the characters are going to say. This includes the internal conversations my characters might have. You see by the time I get to the writing stage I know my characters (I've live with them in my head and often have conversations with them), so when it comes to writing what they say they can do the work for me.

Therefore my answer to Uncle Albert was a bit of both, which seemed to satisfy him as we moved onto another subject.

So my question to the writers reading this is the one I was asked, "do the words just come?"

Regards

LynneI also write for Authors Electric - a collection of writers who have self-published some or all of their work.

Published on May 24, 2014 23:00

May 20, 2014

Food for Thought by Charlotte Guillian

Perhaps it shouldn't have been a surprise to us at the Picture Book Den, but until now we'd never realised how many picture books were about food. Thanks to our guest blogger, children's author Charlotte Guillian (and co-author Adam Guillian), we'll now see food everywhere!

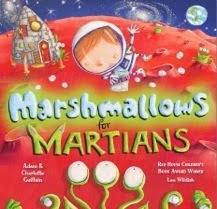

Adam and I recently looked through the picture book ideas we have come up with together and were struck by how many of them involve food! Our first published picture book was Spaghetti with the Yeti, which will be followed later this year by Marshmallows for Martians – and there are other delicious adventures to come in the same series. This got me thinking about the picture books I read growing up and then to my own children – so many great stories involve food, usually of the yummiest kind.

Adam and I recently looked through the picture book ideas we have come up with together and were struck by how many of them involve food! Our first published picture book was Spaghetti with the Yeti, which will be followed later this year by Marshmallows for Martians – and there are other delicious adventures to come in the same series. This got me thinking about the picture books I read growing up and then to my own children – so many great stories involve food, usually of the yummiest kind.

One of the first foodie picture books I remember from my own childhood is Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar. I can remember poring over the spread ‘On Saturday he ate through one piece of chocolate cake…’, wondering what Swiss cheese and salami tasted like (this was the 1970s and Sainsburys didn’t have quite the range it does now…) and deciding whether I’d prefer the chocolate cake or the cherry pie. I was fascinated by the bright pink slice of watermelon and repulsed by the green pickle!

One of the first foodie picture books I remember from my own childhood is Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar. I can remember poring over the spread ‘On Saturday he ate through one piece of chocolate cake…’, wondering what Swiss cheese and salami tasted like (this was the 1970s and Sainsburys didn’t have quite the range it does now…) and deciding whether I’d prefer the chocolate cake or the cherry pie. I was fascinated by the bright pink slice of watermelon and repulsed by the green pickle!

Other childhood favourites for me were John Burningham’s Mr Gumpy books. The spread at the end of Mr Gumpy’s Outing, where everyone sits round the table and enjoys tea together, needs no words as the scene is just so satisfying. I can remember looking at this picture for ages thinking about who I’d like to sit next to! What can be better than a story that ends with a picnic or special tea?

Other childhood favourites for me were John Burningham’s Mr Gumpy books. The spread at the end of Mr Gumpy’s Outing, where everyone sits round the table and enjoys tea together, needs no words as the scene is just so satisfying. I can remember looking at this picture for ages thinking about who I’d like to sit next to! What can be better than a story that ends with a picnic or special tea?

And of course there was Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea. I must have had a deep-seated fear of ever having to miss tea because I can remember the anxiety I felt every time we got to the part when there is no food left in the house. But the wonderful, cosy ending with a trip to a café was just perfect.

And of course there was Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea. I must have had a deep-seated fear of ever having to miss tea because I can remember the anxiety I felt every time we got to the part when there is no food left in the house. But the wonderful, cosy ending with a trip to a café was just perfect.

More recently I’ve enjoyed other food-focused books with my own children. John Vernon Lord’s The Giant Jam Sandwich was a big favourite for us – we loved the ingenious ways the villagers bake a huge loaf of bread and find industrial quantities of butter and jam. And all just to get rid of some wasps! ‘Don’t they want to eat it?’ my daughter would always ask.

More recently I’ve enjoyed other food-focused books with my own children. John Vernon Lord’s The Giant Jam Sandwich was a big favourite for us – we loved the ingenious ways the villagers bake a huge loaf of bread and find industrial quantities of butter and jam. And all just to get rid of some wasps! ‘Don’t they want to eat it?’ my daughter would always ask.

I’ve lost count of the times we’ve read Helen Cooper’s Pumpkin Soup. The illustrations and the text are both equally beautiful and the story sums up perfectly how some friendships are built over sharing (and cooking) delicious food together. We can probably all identify with the way one of the characters behaves in the kitchen – I think I’m probably mostly squirrel but there is definitely at least one duck in our house!

I’ve lost count of the times we’ve read Helen Cooper’s Pumpkin Soup. The illustrations and the text are both equally beautiful and the story sums up perfectly how some friendships are built over sharing (and cooking) delicious food together. We can probably all identify with the way one of the characters behaves in the kitchen – I think I’m probably mostly squirrel but there is definitely at least one duck in our house!

Then of course there’s Lauren Child’s I Will Never Not Ever Eat a Tomato, a modern classic that is so much fun to read aloud as an adult. We still talk about moonsquirters in our house and it’s years since this book featured at bedtime.

Then of course there’s Lauren Child’s I Will Never Not Ever Eat a Tomato, a modern classic that is so much fun to read aloud as an adult. We still talk about moonsquirters in our house and it’s years since this book featured at bedtime.

Another great book that looks at the food children refuse to eat is Caryl Hart’s The Princess and the Peas (illus by Sarah Warburton). The rhyming text is so much fun to share and the story features one of the loveliest dads in picture books!

Another great book that looks at the food children refuse to eat is Caryl Hart’s The Princess and the Peas (illus by Sarah Warburton). The rhyming text is so much fun to share and the story features one of the loveliest dads in picture books!

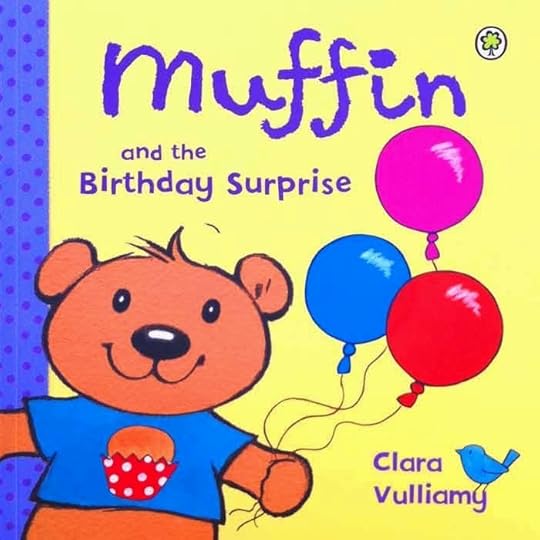

We’ve been trying to think of more books with very child-friendly food in them – chocolate, ice cream, cake, chips… Carla Vulliamy’s Muffin and the Birthday Surprise springs to mind – it captures perfectly that compelling urge to keep trying just a little bit more of something delicious. There must be others out there – what are your favourite foodie picture books?

We’ve been trying to think of more books with very child-friendly food in them – chocolate, ice cream, cake, chips… Carla Vulliamy’s Muffin and the Birthday Surprise springs to mind – it captures perfectly that compelling urge to keep trying just a little bit more of something delicious. There must be others out there – what are your favourite foodie picture books?

Charlotte Guillian

www.tinnedspaghetti.co.uk

Marshmallows for Martians, by Charlotte and Adam Guillian, illus by Lee Wildish,

Marshmallows for Martians, by Charlotte and Adam Guillian, illus by Lee Wildish,

will be published by Egmont,

early June, 2014[image error]

Adam and I recently looked through the picture book ideas we have come up with together and were struck by how many of them involve food! Our first published picture book was Spaghetti with the Yeti, which will be followed later this year by Marshmallows for Martians – and there are other delicious adventures to come in the same series. This got me thinking about the picture books I read growing up and then to my own children – so many great stories involve food, usually of the yummiest kind.

Adam and I recently looked through the picture book ideas we have come up with together and were struck by how many of them involve food! Our first published picture book was Spaghetti with the Yeti, which will be followed later this year by Marshmallows for Martians – and there are other delicious adventures to come in the same series. This got me thinking about the picture books I read growing up and then to my own children – so many great stories involve food, usually of the yummiest kind. One of the first foodie picture books I remember from my own childhood is Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar. I can remember poring over the spread ‘On Saturday he ate through one piece of chocolate cake…’, wondering what Swiss cheese and salami tasted like (this was the 1970s and Sainsburys didn’t have quite the range it does now…) and deciding whether I’d prefer the chocolate cake or the cherry pie. I was fascinated by the bright pink slice of watermelon and repulsed by the green pickle!

One of the first foodie picture books I remember from my own childhood is Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar. I can remember poring over the spread ‘On Saturday he ate through one piece of chocolate cake…’, wondering what Swiss cheese and salami tasted like (this was the 1970s and Sainsburys didn’t have quite the range it does now…) and deciding whether I’d prefer the chocolate cake or the cherry pie. I was fascinated by the bright pink slice of watermelon and repulsed by the green pickle!  Other childhood favourites for me were John Burningham’s Mr Gumpy books. The spread at the end of Mr Gumpy’s Outing, where everyone sits round the table and enjoys tea together, needs no words as the scene is just so satisfying. I can remember looking at this picture for ages thinking about who I’d like to sit next to! What can be better than a story that ends with a picnic or special tea?

Other childhood favourites for me were John Burningham’s Mr Gumpy books. The spread at the end of Mr Gumpy’s Outing, where everyone sits round the table and enjoys tea together, needs no words as the scene is just so satisfying. I can remember looking at this picture for ages thinking about who I’d like to sit next to! What can be better than a story that ends with a picnic or special tea? And of course there was Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea. I must have had a deep-seated fear of ever having to miss tea because I can remember the anxiety I felt every time we got to the part when there is no food left in the house. But the wonderful, cosy ending with a trip to a café was just perfect.

And of course there was Judith Kerr’s The Tiger Who Came to Tea. I must have had a deep-seated fear of ever having to miss tea because I can remember the anxiety I felt every time we got to the part when there is no food left in the house. But the wonderful, cosy ending with a trip to a café was just perfect. More recently I’ve enjoyed other food-focused books with my own children. John Vernon Lord’s The Giant Jam Sandwich was a big favourite for us – we loved the ingenious ways the villagers bake a huge loaf of bread and find industrial quantities of butter and jam. And all just to get rid of some wasps! ‘Don’t they want to eat it?’ my daughter would always ask.

More recently I’ve enjoyed other food-focused books with my own children. John Vernon Lord’s The Giant Jam Sandwich was a big favourite for us – we loved the ingenious ways the villagers bake a huge loaf of bread and find industrial quantities of butter and jam. And all just to get rid of some wasps! ‘Don’t they want to eat it?’ my daughter would always ask. I’ve lost count of the times we’ve read Helen Cooper’s Pumpkin Soup. The illustrations and the text are both equally beautiful and the story sums up perfectly how some friendships are built over sharing (and cooking) delicious food together. We can probably all identify with the way one of the characters behaves in the kitchen – I think I’m probably mostly squirrel but there is definitely at least one duck in our house!

I’ve lost count of the times we’ve read Helen Cooper’s Pumpkin Soup. The illustrations and the text are both equally beautiful and the story sums up perfectly how some friendships are built over sharing (and cooking) delicious food together. We can probably all identify with the way one of the characters behaves in the kitchen – I think I’m probably mostly squirrel but there is definitely at least one duck in our house! Then of course there’s Lauren Child’s I Will Never Not Ever Eat a Tomato, a modern classic that is so much fun to read aloud as an adult. We still talk about moonsquirters in our house and it’s years since this book featured at bedtime.

Then of course there’s Lauren Child’s I Will Never Not Ever Eat a Tomato, a modern classic that is so much fun to read aloud as an adult. We still talk about moonsquirters in our house and it’s years since this book featured at bedtime. Another great book that looks at the food children refuse to eat is Caryl Hart’s The Princess and the Peas (illus by Sarah Warburton). The rhyming text is so much fun to share and the story features one of the loveliest dads in picture books!

Another great book that looks at the food children refuse to eat is Caryl Hart’s The Princess and the Peas (illus by Sarah Warburton). The rhyming text is so much fun to share and the story features one of the loveliest dads in picture books! We’ve been trying to think of more books with very child-friendly food in them – chocolate, ice cream, cake, chips… Carla Vulliamy’s Muffin and the Birthday Surprise springs to mind – it captures perfectly that compelling urge to keep trying just a little bit more of something delicious. There must be others out there – what are your favourite foodie picture books?

We’ve been trying to think of more books with very child-friendly food in them – chocolate, ice cream, cake, chips… Carla Vulliamy’s Muffin and the Birthday Surprise springs to mind – it captures perfectly that compelling urge to keep trying just a little bit more of something delicious. There must be others out there – what are your favourite foodie picture books?Charlotte Guillian

www.tinnedspaghetti.co.uk

Marshmallows for Martians, by Charlotte and Adam Guillian, illus by Lee Wildish,

Marshmallows for Martians, by Charlotte and Adam Guillian, illus by Lee Wildish,will be published by Egmont,

early June, 2014[image error]

Published on May 20, 2014 00:00

May 14, 2014

The first picture book I bought for my first grandchild by Jane Clarke

I'm a grandma! Yaaay!

My granddaughter, currently known as Peanut, arrived a month early, and she can’t keep her eyes open for long yet - but I can't wait to introduce her to picture books. Here she is in my son's hands.

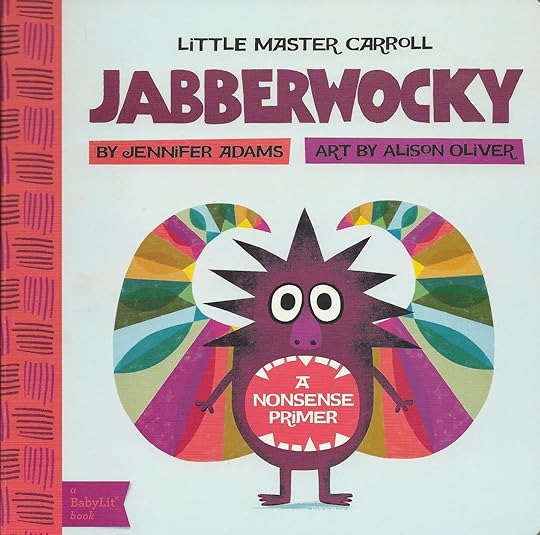

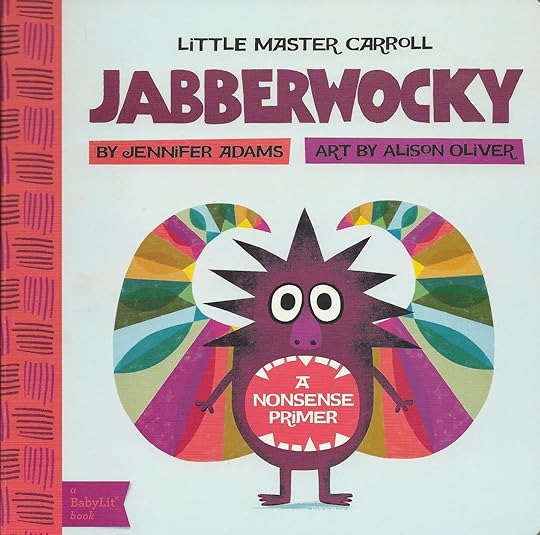

I bought her a picture book when she was just a bump. It wasn't planned – I was browsing aimlessly in the shop in the British Library and this jumped out at me:

So, out of all the wonderful picture books in print today, why did I choose this little board book?

It's a heavily edited, lighthearted version of Jabberwocky by Lewis Carol - a poem Peanut's grandfather, my late husband Martin, had to lean by heart when he was at school. I have very happy memories of Martin reciting the lines (often in the wrong order) in a funny voice and making our sons chortle when they were tiny.

I hope this book with its daft verse and surreal illustrations will make Peanut giggle too - and hear an echo of the grandpa she will never meet.

And of course – it's only the start of a big collection. So back to the rejoicing…

What was the first picture book you bought for your child or grandchild?

My granddaughter, currently known as Peanut, arrived a month early, and she can’t keep her eyes open for long yet - but I can't wait to introduce her to picture books. Here she is in my son's hands.

I bought her a picture book when she was just a bump. It wasn't planned – I was browsing aimlessly in the shop in the British Library and this jumped out at me:

So, out of all the wonderful picture books in print today, why did I choose this little board book?

It's a heavily edited, lighthearted version of Jabberwocky by Lewis Carol - a poem Peanut's grandfather, my late husband Martin, had to lean by heart when he was at school. I have very happy memories of Martin reciting the lines (often in the wrong order) in a funny voice and making our sons chortle when they were tiny.

I hope this book with its daft verse and surreal illustrations will make Peanut giggle too - and hear an echo of the grandpa she will never meet.

And of course – it's only the start of a big collection. So back to the rejoicing…

What was the first picture book you bought for your child or grandchild?

Published on May 14, 2014 23:30

May 11, 2014

What We've Learned Along The Way - Group Post Part One

Back in the mists of time we were all unpublished authors. Some of us had a background in publishing before we gained the 'label' of author, some of us did not. However one thing we all share is that we have all learned something along the way. In this post some of our team share one of the things we learned.

Abie Longstaff Play. Sometimes we get caught up in the business side of writing: we write 'for the market' or because a publisher has asked us to write a particular story they have a slot for. But the best stories often come from simply playing with an idea just for the idea itself. You can work it and rework it; change theme or character or word length and it becomes something very different. If I get stuck I often draw - it helps me keep the story light and fun and reminds me to keep playing.

Jane Clarke

You can take a very simple, ordinary idea that develops out of something that happens to you or your family and and twist it so it becomes something special. Gilbert the Hero, illustrated by Charles Fuge, is based on how my older son reacted to the arrival of his baby brother.

Lynne Garner Enjoy playing with words. When writing a picture book try exploring rhyme, rhythm or repetition. Using any or all can change a good story into one that captures the imagination and is a joy to read.

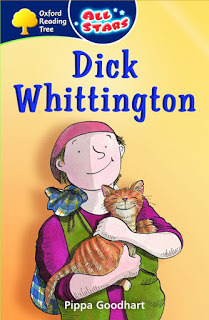

Pippa Goodhart

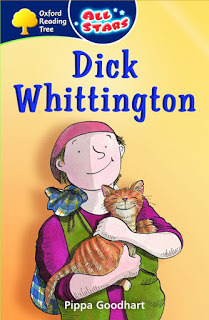

Develop a strange personality that is part-arrogant, part-modest. You need the arrogance to believe in your best ideas, even when others, including publishers, don't. You need persistence to keep trying, working out how you might make those vital publishing minds see your vision in the same way that you do. But you also need the modesty to recognise when your ideas are not strong enough to compete with all those wonderful pictures books already published, or simply don't suit the format or the market ... at which point the arrogant side kicks in again, and you see if you can use that precious idea in some other way that WILL excite publishers and book buyers! So, for example, the wonderful large full colour picture book story of Dick Whittington that I loved ... became a much smaller and simpler little book that is published as in OUP reading book.

We hope you have enjoyed reading about our experiences. We've enjoyed sharing.

Abie Longstaff Play. Sometimes we get caught up in the business side of writing: we write 'for the market' or because a publisher has asked us to write a particular story they have a slot for. But the best stories often come from simply playing with an idea just for the idea itself. You can work it and rework it; change theme or character or word length and it becomes something very different. If I get stuck I often draw - it helps me keep the story light and fun and reminds me to keep playing.

Jane Clarke

You can take a very simple, ordinary idea that develops out of something that happens to you or your family and and twist it so it becomes something special. Gilbert the Hero, illustrated by Charles Fuge, is based on how my older son reacted to the arrival of his baby brother.

Lynne Garner Enjoy playing with words. When writing a picture book try exploring rhyme, rhythm or repetition. Using any or all can change a good story into one that captures the imagination and is a joy to read.

Pippa Goodhart

Develop a strange personality that is part-arrogant, part-modest. You need the arrogance to believe in your best ideas, even when others, including publishers, don't. You need persistence to keep trying, working out how you might make those vital publishing minds see your vision in the same way that you do. But you also need the modesty to recognise when your ideas are not strong enough to compete with all those wonderful pictures books already published, or simply don't suit the format or the market ... at which point the arrogant side kicks in again, and you see if you can use that precious idea in some other way that WILL excite publishers and book buyers! So, for example, the wonderful large full colour picture book story of Dick Whittington that I loved ... became a much smaller and simpler little book that is published as in OUP reading book.

We hope you have enjoyed reading about our experiences. We've enjoyed sharing.

Published on May 11, 2014 12:03

May 4, 2014

A Change of Character by Michelle Robinson

Characters have always felt like a chink in my armour. When I’m writing a picture book, I tend to work roughly like this:-

- Concept- Work out the best beginning, middle and end- Write it down(Ah, I make it sound so simple! Trust me, there's always plenty of brain ache involved along the way).

Sometimes the order I work in changes, and there’s usually a lot of revisiting any one - or all three - of those steps to find the right voice and whatnot, but that’s really about it. I’ve always known there’s something missing in my approach: CHARACTER.

Oops.

Characters are what publishers want to see and who readers want to meet. Yes, they want great stories, but the key to really hooking people is who that story belongs to. Who's unique voice are we hearing? Who are we going to side with? Fall in love with? Worry about? Tut at? Snuggle up with by the glow of our night light?

The trouble with my natural approach writing is this: characters are often just the person (or chicken/gorilla/mammoth) the plot happens to. That’s not to say they aren’t good or believable characters, because I usually manage to get the reader to bond with them emotionally. But they're certainly not as strong as they could be; not multi-book-TV-series-and-a-cuddly-toy strong. That's often what lets my stories down at acquisitions meetings, if they make it that far.

No merchandise? Get your illustrator's mum to make it. Thanks, Mama Hindley!

No merchandise? Get your illustrator's mum to make it. Thanks, Mama Hindley!

Not one to mope over criticism, especially when it echoes something I already know, deep down, I recently took myself on a one day course in 'Character Mapping'.

I had to smile to myself as I sat in the lecture theatre, taking notes as the inventor of 'Character Mapping', Laurie Hutzler passed on her wisdom - and she really is wise (and perceptive, fast and funny - highly recommended). Sure, Laurie comes from a screenwriting background, but her approach to storytelling translates to picture books, too. I found myself smiling wryly as she spoke about characters needing to face up to their fears instead of holding back from becoming their truest, bestest selves. She may as well have been talking about me.

I took 26 pages of workshop notes. TWENTY SIX.

I took 26 pages of workshop notes. TWENTY SIX.

I do hold back. I worry that I can’t create great characters, so I don’t risk trying. I stick to what I know - concepts, plotting, word play. Not any more!

Now I have new, improved SUPER POWERS and the knowhow to create stories that start and end with characters - authentic ones who act just the way they ought to as individuals. Even if they are completely made up, even if they do live on the moon and have five legs, they will behave in a way that is totally real and - in true picture book style - totally relatable.

I like to think I had something to do with creating the characters in

I like to think I had something to do with creating the characters in

There's A Lion In My Cornflakes, but I suspect it was all Jim Field's doing.

So I'm going to try breaking the habit of a lifetime, starting with character rather than concept. It can't hurt to try. I won't necessarily use the full 'Character Map' to do it - although I would certainly use it for longer fiction - but I'll use some of the lessons I learned along the way. Lessons like:-

- 'TELL ME MORE!' the required response from a reader when they first meet a character

- THE DEFINITION OF 'TO BE ENTERTAINED' IS TO FEEL SOMETHING if the reader isn't feeling something, they're not being entertained - and they'll lose interest

- To that end: NOTHING IS MEMORABLE UNLESS THERE'S A FEELING ATTACHED

- To create emotional connection you need VULNERABILITY and VERISIMILITUDE

- And in comedy, IF IT DOESN'T HURT, IT ISN'T FUNNY

I love that last one. I also wrote down 'DELIVER SOMETHING EXPECTED IN AN UNEXPECTED WAY'. That sounds awesome, if quite a challenge. My unexpected way is going to start with the writing process itself, by putting character at the heart of my stories. What's the worst that can happen? If I do find I'm naturally, incurably concept-driven, from now on at least I'll always write with much more awareness of character and they won't just fall out of a plot ever again. (I might at least add one sentence that shows I've thought about them...)

You can read about Laurie Hutzler's 'Character Mapping' in detail here. You'll want to free up some time and get yourself a whole pot of tea first, it's quite detailed and lengthy, but it's very good.

Thanks for reading, I hope it helps you think about the way you write. I'm off to enjoy today's Bank Holiday with two very real, very chirpy characters who have been acting true to form by bouncing on the bed next to me while I typed. Please excuse any typos.

For more on Michelle Robinson, including writing advice, colouring sheets and free audio games to accompany her picture books, visit her website.

- Concept- Work out the best beginning, middle and end- Write it down(Ah, I make it sound so simple! Trust me, there's always plenty of brain ache involved along the way).

Sometimes the order I work in changes, and there’s usually a lot of revisiting any one - or all three - of those steps to find the right voice and whatnot, but that’s really about it. I’ve always known there’s something missing in my approach: CHARACTER.

Oops.

Characters are what publishers want to see and who readers want to meet. Yes, they want great stories, but the key to really hooking people is who that story belongs to. Who's unique voice are we hearing? Who are we going to side with? Fall in love with? Worry about? Tut at? Snuggle up with by the glow of our night light?

The trouble with my natural approach writing is this: characters are often just the person (or chicken/gorilla/mammoth) the plot happens to. That’s not to say they aren’t good or believable characters, because I usually manage to get the reader to bond with them emotionally. But they're certainly not as strong as they could be; not multi-book-TV-series-and-a-cuddly-toy strong. That's often what lets my stories down at acquisitions meetings, if they make it that far.

No merchandise? Get your illustrator's mum to make it. Thanks, Mama Hindley!

No merchandise? Get your illustrator's mum to make it. Thanks, Mama Hindley!Not one to mope over criticism, especially when it echoes something I already know, deep down, I recently took myself on a one day course in 'Character Mapping'.

I had to smile to myself as I sat in the lecture theatre, taking notes as the inventor of 'Character Mapping', Laurie Hutzler passed on her wisdom - and she really is wise (and perceptive, fast and funny - highly recommended). Sure, Laurie comes from a screenwriting background, but her approach to storytelling translates to picture books, too. I found myself smiling wryly as she spoke about characters needing to face up to their fears instead of holding back from becoming their truest, bestest selves. She may as well have been talking about me.

I took 26 pages of workshop notes. TWENTY SIX.

I took 26 pages of workshop notes. TWENTY SIX.I do hold back. I worry that I can’t create great characters, so I don’t risk trying. I stick to what I know - concepts, plotting, word play. Not any more!

Now I have new, improved SUPER POWERS and the knowhow to create stories that start and end with characters - authentic ones who act just the way they ought to as individuals. Even if they are completely made up, even if they do live on the moon and have five legs, they will behave in a way that is totally real and - in true picture book style - totally relatable.

I like to think I had something to do with creating the characters in

I like to think I had something to do with creating the characters in There's A Lion In My Cornflakes, but I suspect it was all Jim Field's doing.

So I'm going to try breaking the habit of a lifetime, starting with character rather than concept. It can't hurt to try. I won't necessarily use the full 'Character Map' to do it - although I would certainly use it for longer fiction - but I'll use some of the lessons I learned along the way. Lessons like:-

- 'TELL ME MORE!' the required response from a reader when they first meet a character

- THE DEFINITION OF 'TO BE ENTERTAINED' IS TO FEEL SOMETHING if the reader isn't feeling something, they're not being entertained - and they'll lose interest

- To that end: NOTHING IS MEMORABLE UNLESS THERE'S A FEELING ATTACHED

- To create emotional connection you need VULNERABILITY and VERISIMILITUDE

- And in comedy, IF IT DOESN'T HURT, IT ISN'T FUNNY

I love that last one. I also wrote down 'DELIVER SOMETHING EXPECTED IN AN UNEXPECTED WAY'. That sounds awesome, if quite a challenge. My unexpected way is going to start with the writing process itself, by putting character at the heart of my stories. What's the worst that can happen? If I do find I'm naturally, incurably concept-driven, from now on at least I'll always write with much more awareness of character and they won't just fall out of a plot ever again. (I might at least add one sentence that shows I've thought about them...)

You can read about Laurie Hutzler's 'Character Mapping' in detail here. You'll want to free up some time and get yourself a whole pot of tea first, it's quite detailed and lengthy, but it's very good.

Thanks for reading, I hope it helps you think about the way you write. I'm off to enjoy today's Bank Holiday with two very real, very chirpy characters who have been acting true to form by bouncing on the bed next to me while I typed. Please excuse any typos.

For more on Michelle Robinson, including writing advice, colouring sheets and free audio games to accompany her picture books, visit her website.

Published on May 04, 2014 23:00

April 29, 2014

Events for the picture book age group by Abie Longstaff

I do lots of events: in schools, in shops and at lit fests. Performing was really scary at first but I've got better over the years and I've learned a few tricks along the way!

1. Pre-event

The more effort the event organiser puts in, the better your reading will be. If a shop books me I try to engage with them in the run-up to the show, making sure there are advertisements, posters in the window, notices on local forums; anything to get the message out to parents.

Sometimes the shop needs a bit of a nudge to do this - I often ask my lovely publicist at my publisher to help here. Publishers can make a range of fantastic posters and showcards.

2. Prepare

What are you going to do?

I start by reading a story

I talk about how I make a book: where my ideas come from, my writing process, the editing stages.

then we play games - for The Fairytale Hairdresser we play salons.

I have some great dolls with really strong hair that can be brushed, pulled and pinned and we spend ages putting in clips and ribbons. I also have pirate outfits for Pirate House Swap and some fantastic puppets for The Mummy Shop.

There are colour-in activity sheets...and sometimes we even have cake!

Work out your event in chunks of time. It's really important to know how long each segment takes so you can plan and so that, on the day, if you only have ten minutes left, you know which segment to do.

3. Know your age group

Children of 2-6 don't sit still for long! You have to work hard to engage them. I find sitting with them on the floor really helps because it keeps you in their eye-line and you can hold their attention more easily. I ask them lots of questions as I read: about the pictures and what they can see; about how they think a character feels; about what might happen next. I try to make it a bit like being read to at home, a chatty cosy time so they feel at ease and confident.

Don't forget, along with your target age group will come their parents (who also need to be engaged with and chatted to) and often a much younger sibling.

If you watch the audience you can see when the children start getting wriggly and itchy - spot trouble before it happens and change to another activity.

4. Think about actions, pictures and sounds

When you are reading it is very easy to get caught up in the words. Don't forget to points things out in the illustrations. Ask the children to make sounds - horns, doorbells, rain, animal noises; whatever suits your texts. I get to hear some pretty evil witch cackles! The same applies for actions - we spend time plaiting Rapunzel's hair along with the fairytale hairdresser.

If I'm lucky enough to have the illustrator (Lauren Beard) with me there is a whole new dimension to the event - she draws as I talk and the children can really see the story come to life!

5. Questions

This age group come out with some fantastic questions. They often don't understand that a book is printed - I'm usually asked how I make my writing so neat in the printed books and if it took me ages to write out each book by hand! I ask them how long they think it takes between my first idea and the book ending up on the shelf in a shop. If I really could make that process happen in a day or a week I'd be a very prolific author indeed!

They also tend to spot tiny elements of the illustration that can pass adults by. Be prepared to explain the drawings as well as the words in the story. Get to know every inch of your book. And be prepared for off the wall comments. My favourite question has to be from the little boy who put up his hand to say proudly:

"I had pineapple for breakfast"

I'd love to hear your tips on events!

Have a look on my website for my future events

Book to see Lauren and me at Hay-onWye Lit Fest here

1. Pre-event

The more effort the event organiser puts in, the better your reading will be. If a shop books me I try to engage with them in the run-up to the show, making sure there are advertisements, posters in the window, notices on local forums; anything to get the message out to parents.

Sometimes the shop needs a bit of a nudge to do this - I often ask my lovely publicist at my publisher to help here. Publishers can make a range of fantastic posters and showcards.

2. Prepare

What are you going to do?

I start by reading a story

I talk about how I make a book: where my ideas come from, my writing process, the editing stages.

then we play games - for The Fairytale Hairdresser we play salons.

I have some great dolls with really strong hair that can be brushed, pulled and pinned and we spend ages putting in clips and ribbons. I also have pirate outfits for Pirate House Swap and some fantastic puppets for The Mummy Shop.

There are colour-in activity sheets...and sometimes we even have cake!

Work out your event in chunks of time. It's really important to know how long each segment takes so you can plan and so that, on the day, if you only have ten minutes left, you know which segment to do.

3. Know your age group

Children of 2-6 don't sit still for long! You have to work hard to engage them. I find sitting with them on the floor really helps because it keeps you in their eye-line and you can hold their attention more easily. I ask them lots of questions as I read: about the pictures and what they can see; about how they think a character feels; about what might happen next. I try to make it a bit like being read to at home, a chatty cosy time so they feel at ease and confident.

Don't forget, along with your target age group will come their parents (who also need to be engaged with and chatted to) and often a much younger sibling.

If you watch the audience you can see when the children start getting wriggly and itchy - spot trouble before it happens and change to another activity.

4. Think about actions, pictures and sounds

When you are reading it is very easy to get caught up in the words. Don't forget to points things out in the illustrations. Ask the children to make sounds - horns, doorbells, rain, animal noises; whatever suits your texts. I get to hear some pretty evil witch cackles! The same applies for actions - we spend time plaiting Rapunzel's hair along with the fairytale hairdresser.

If I'm lucky enough to have the illustrator (Lauren Beard) with me there is a whole new dimension to the event - she draws as I talk and the children can really see the story come to life!

5. Questions

This age group come out with some fantastic questions. They often don't understand that a book is printed - I'm usually asked how I make my writing so neat in the printed books and if it took me ages to write out each book by hand! I ask them how long they think it takes between my first idea and the book ending up on the shelf in a shop. If I really could make that process happen in a day or a week I'd be a very prolific author indeed!

They also tend to spot tiny elements of the illustration that can pass adults by. Be prepared to explain the drawings as well as the words in the story. Get to know every inch of your book. And be prepared for off the wall comments. My favourite question has to be from the little boy who put up his hand to say proudly:

"I had pineapple for breakfast"

I'd love to hear your tips on events!

Have a look on my website for my future events

Book to see Lauren and me at Hay-onWye Lit Fest here

Published on April 29, 2014 22:59

April 24, 2014

Ten Really Cool Picture Book Openings and Why They Matter

By Natascha Biebow

I bet you are reading this first line thinking where is this blog post going and is it worth my while reading on?

I know. I’m the kind of person who picks up a book, glances at the back cover and flips right to the opening page. Once I’ve read the opening lines, I can tell right away if I am hooked, whether I want to read on. Because the opening line gives me a really clear idea of the journey that the author is proposing.

I quickly decide: is this a journey upon which I want to spend my precious time?

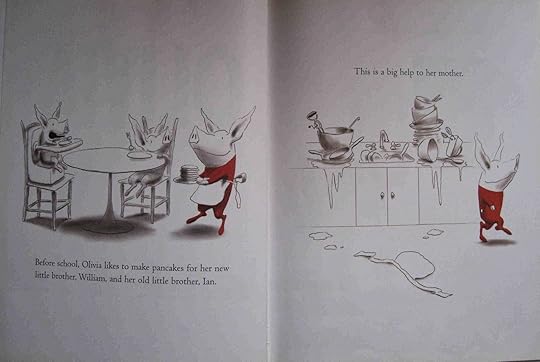

For instance, here's an opening I love, from Olivia Saves the Circus by Ian Falconer:

"Before school, Olivia likes to make pancakes for her newlittle brother, William, and her old little brother, Ian.

This is a big help to her mother."

Olivia Saves the Circus © Falconer

Olivia Saves the Circus © Falconer It sets up right away that Olivia is quite a character –- one that I'd like to spend time with! Also, I am intrigued by the voice which uses phrases like "old little brother". Importantly, the opening sets up that Olivia unwittingly equals trouble and, as a reader, I want to find out what she'll get up to next. (She goes on to do amazing circus acts with cool aplomb).

Editors and agents, who receive hundreds of submissions, are the same -- they have got to love the opening of a book to want to publish it.

But picture book openings are notoriously difficult to get right. They are so few words for a start . . . Plus how will a story grab so many different people -– children, parents, elusive editors and agents -- at once?!

Importantly, a fantastic opening contains the premise and situation of the whole book. In the classic We're Going on a Bear Hunt by Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury, the opening line states right off the bat: "We're going on a bear hunt". Then, the author invites readers on an adventure that appeals to children and grown-ups alike.

We're Going on a Bear Hunt © Rosen & Oxenbury

We're Going on a Bear Hunt © Rosen & OxenburyAlmost immediately, we encounter our first challenge -- long wavy grass. Oooh, we've got to wade through it . . . We want to join in! This opening also sets out the mood, tone and authorial voice. Do we want to go on this adventure? Of course we do -- we want to find out what the bear is like!

There are three key elements to every good opening: who, what and where?

1. Who? introduces the main character and tells readers who's going on the journey

In Penguin by Polly Dunbar, the book opens with the main character, Ben, receiving a penguin as a present. Why does Ben get a penguin, we wonder? What if this were us? What will happen next?

Penguin © Dunbar

Penguin © DunbarThe opening in The Pig Who Wished by Joyce Dunbar and Selina Young is equally intriguing. Though the phrasing is more traditional ("Once ..."), it quickly sets up that the main character is a pig with a difference, plus it promises a story with magic!

The Pig Who Wished © Dunbar & Young

The Pig Who Wished © Dunbar & Young2. Where? sets the scene for the story, including the setting and the circumstances of the main action.

In the classic The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle, readers are enticed into the world of the little egg. We know we are in the natural world, full of promise and wonder.

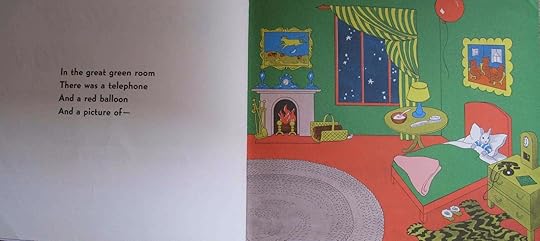

The Very Hungry Caterpillar © CarleBy contrast, the setting in Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd is very domestic, but filled with interesting details. The rhythm of the voice is quickly established and the familiarity of the child's world promises a comforting journey with this narrator.

The Very Hungry Caterpillar © CarleBy contrast, the setting in Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd is very domestic, but filled with interesting details. The rhythm of the voice is quickly established and the familiarity of the child's world promises a comforting journey with this narrator. Goodnight Moon © Wise Brown & Hurd

Goodnight Moon © Wise Brown & Hurd3. What? sets up the main conflict and motivation of the character (what do they need?) that is going to drive them forwards.

In the first spread of Eat Your Peas by Kes Gray and Nick Sharratt, we meet Daisy and her mum at loggerheads over dinner -- how will they resolve their differences?

Eat Your Peas © Gray & Sharratt

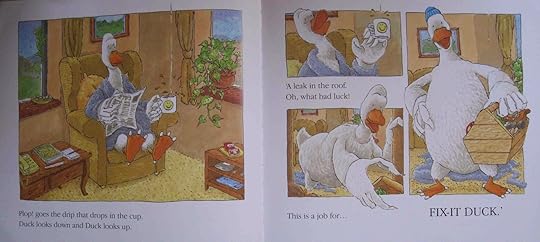

Eat Your Peas © Gray & SharrattSimilarly in the opening lines of Fix It Duck by Jez Alborough, we meet the main character, Duck, who has a pressing problem -- a leak in the roof -- and whose fixing prowess, we later discover, is decidedly dodgy. Readers are immediately drawn into the rhythmical storytelling of this author's voice.

Fix It Duck © Alborough

Fix It Duck © AlboroughOften, authors will employ a few spreads to set up the story, but the really clever openings can do this in just a couple of lines and even on one page. Here are five great ways to grab readers in the opening lines:

1. Give a hint of things to come

Emily Brown and the Elephant Emergency © Cowell & Layton

Emily Brown and the Elephant Emergency © Cowell & LaytonIn the first spread of Emily Brown and the Elephant Emergency by Cressida Cowell and Neal Layton, we meet Emily, Stanley and their friend Matilda. We jump right into an exciting adventure (one of many to come) and are intrigued to find out what will happen next.

2. Start in the middle of the action

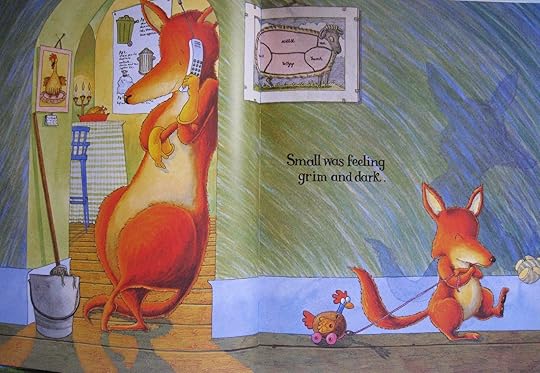

No Matter What © Gliori

No Matter What © GlioriIn this opening from No Matter What by Debi Gliori, the reader is thrown right into the middle of a situation -– Small is feeling grumpy. We want to know why he is grumpy and how will it be resolved. More than likely, we have been there ourselves, too, so we can empathise!

3. get readers’ attention so they want to know what’s next

The Tiger Who Came to Tea © Kerr

The Tiger Who Came to Tea © KerrIn The Tiger Who Came to Tea by Judith Kerr, readers are invited into a comfortingly ordinary scenario, but the promise of someone at the door (and the hint in the title) are intriguing enough to get readers to want to read on.

4. allude to familiar situations (we’ve all been there type scenarios)

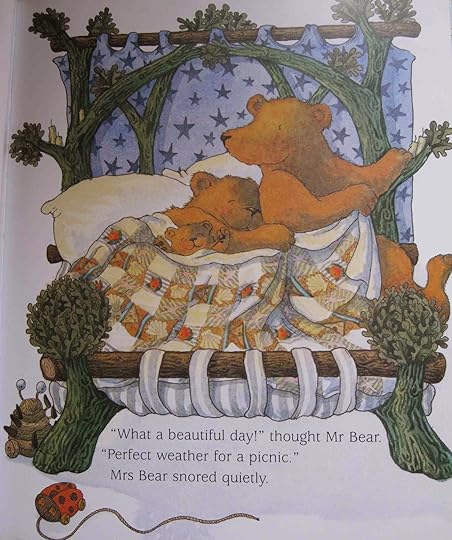

Mr Bear's Picnic © GlioriDebi Gliori is a master at capturing domestic situations in a light-hearted and poignant way that appeals to adults and children alike. In Mr Bear's Picnic, the prospect of a sunny day with children is a great opportunity for a picnic. But Mrs Bear, who has two little ones, is determined to catch some extra shut-eye. The role of Mr Bear as the adult leader and the source of humour is set up in just a few lines.

Mr Bear's Picnic © GlioriDebi Gliori is a master at capturing domestic situations in a light-hearted and poignant way that appeals to adults and children alike. In Mr Bear's Picnic, the prospect of a sunny day with children is a great opportunity for a picnic. But Mrs Bear, who has two little ones, is determined to catch some extra shut-eye. The role of Mr Bear as the adult leader and the source of humour is set up in just a few lines. 5. introduce really intriguing characters and situations

If You Give a Mouse a Cookie © Numeroff & Bond

If You Give a Mouse a Cookie © Numeroff & Bond Laura Numeroff and Felicia Bond's bestselling classic If You Give a Mouse a Cookie sets up straight away a set of unusual characters in an intrguing situation.

Why would you offer a mouse a cookie and what would happen if you did?

If You Give a Mouse a Cookie © Numeroff & Bond

If You Give a Mouse a Cookie © Numeroff & Bond Well, the mouse would want a glass of milk, which would lead to a whole host of other things and back to a cookie. The circular structure of the story is skillfully crafted and really satisfying, but what really grabs you is the premise.

So, with just a few words (and great illustrations!), picture book authors can create openings that make readers want to read on. But what all these openings do is pique readers' curiosity. If readers are saying 'so what?' then the author has lost them . . . Now, about that blank page staring at you . . . What will its opening lines be?

Natascha BiebowAuthor, Editor and Mentor

Blue Elephant Storyshaping is an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Natascha is also the author of Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Regional Advisor (Chair) of SCBWI British Isles. www.blueelephantstoryshaping.com

Blue Elephant Storyshaping is an editing, coaching and mentoring service aimed at empowering writers and illustrators to fine-tune their work pre-submission. Natascha is also the author of Elephants Never Forget and Is This My Nose?, editor of numerous award-winning children’s books, and Regional Advisor (Chair) of SCBWI British Isles. www.blueelephantstoryshaping.com

Published on April 24, 2014 23:00