Moira Butterfield's Blog, page 63

May 10, 2015

The Fifties - Didn't we have them once already? - Jonathan Allen

Well, fashions come and go in the world of children's books. I've been only vaguely aware of it throughout my time in the business, but recently it has really become much more obvious. We are in the middle (or the end, please. . .) of a 1950s obsession, and it's starting to get depressing. it's pretty universal, not just children's books, but this is a grumpy rant about Picture Books so I won't go into fabric and interior design. . . ;-)

Not that the style in question is depressing per se, just that the unoriginality of a lot of the stuff out there is depressing. It's the law of diminishing returns, people mindlessly copying people who are copying people who are copying people who are aping particular 1950's styles like that of the wonderful Miroslav Sasek -

http://www.miroslavsasek.com/index.html

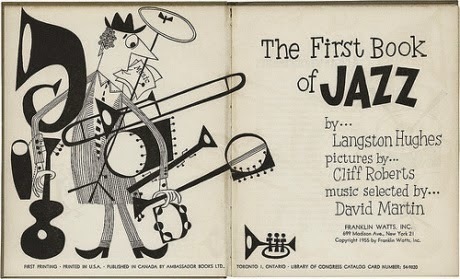

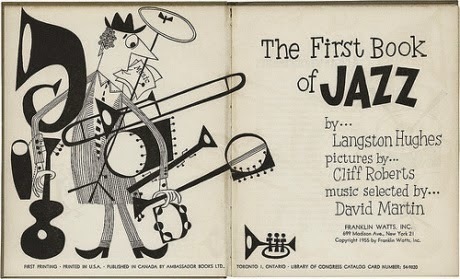

http://www.miroslavsasek.com/index.html– and Cliff Roberts -

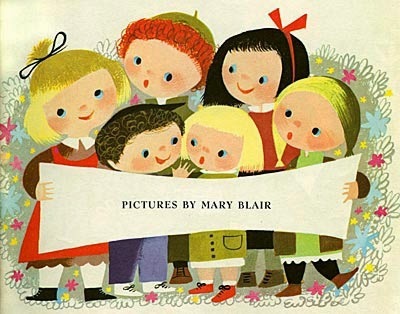

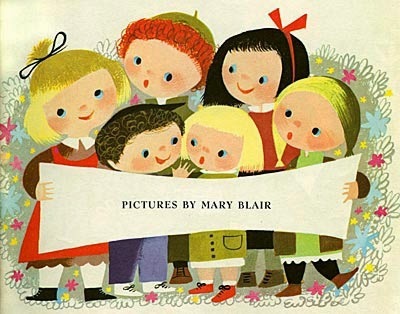

and Mary Blair -

and the also wonderful Margaret Bloy Graham -

And Jim Flora -

Don't get me wrong, I love those original artists, and I love the best of the current artists that are influenced by them. There is nothing wrong with being influenced by others, even copying if it leads to your own style.

But. . . . I lose the will to live when I see a style being done to death by those who really should be trying to work out their own style and their own take on the world. Why do they do it? Is it a lack of confidence, or of self respect?

I never understood unthinking fashion following in the first place so it puts me at a disadvantage I guess. Not that I'm trying to occupy some sort of moral high ground. Well, maybe I'll claim a molehill's worth of hieght. After all, we all see ourselves as paragons of discernment, however delusional that view might be, I'm no different ;-)

Is it wholly market led? It may be that the market has pushed artists in this direction. If something is doing well, publishers will want more stuff like it of course.

Is there some correlation between our times and the fifties that leads people to this abstracted, flat, design led style? To the distance these styles keep the viewer from their subject? The fifties seems to have been a time when Modern was seen as good. Now in our more pessimistic times are we nostalgic about that idea and view of The Modern?

Are things so tough and uncertain that we want to stand a safe distance from the world, especially the world we present to our kids? I'm not any kind of psychologist so I don't know the answer to these questions, but I find the idea interesting.

What I do know is that I for one am getting bored sick of it. It's the illustration world's equivalent of all those young men with big beards, shaved sides of heads and plaid/check shirts ;-) That's getting really old too.

Talking of 'old', put the word 'grumpy' and 'man' in there too and you've defined me absolutely. . .

So as a card carrying Grumpy Old Man confronted by this Fifties obsession, I will say, as I've heard Americans say, 'Stick a fork in it and turn it over, it's done!'

Published on May 10, 2015 00:00

The Fifties - Didn't we have them once already?

Well, fashions come and go in the world of children's books. I've been only vaguely aware of it throughout my time in the business, but recently it has really become much more obvious. We are in the middle (or the end, please. . .) of a 1950s obsession, and it's starting to get depressing. it's pretty universal, not just children's books, but this is a grumpy rant about Picture Books so I won't go into fabric and interior design. . . ;-)

Not that the style in question is depressing per se, just that the unoriginality of a lot of the stuff out there is depressing. It's the law of diminishing returns, people mindlessly copying people who are copying people who are copying people who are aping particular 1950's styles like that of the wonderful Miroslav Sasek -

http://www.miroslavsasek.com/index.html

http://www.miroslavsasek.com/index.html– and Cliff Roberts -

and Mary Blair -

and the also wonderful Margaret Bloy Graham -

And Jim Flora -

Don't get me wrong, I love those original artists, and I love the best of the current artists that are influenced by them. There is nothing wrong with being influenced by others, even copying if it leads to your own style.

But. . . . I lose the will to live when I see a style being done to death by those who really should be trying to work out their own style and their own take on the world. Why do they do it? Is it a lack of confidence, or of self respect?

I never understood unthinking fashion following in the first place so it puts me at a disadvantage I guess. Not that I'm trying to occupy some sort of moral high ground. Well, maybe I'll claim a molehill's worth of hieght. After all, we all see ourselves as paragons of discernment, however delusional that view might be, I'm no different ;-)

Is it wholly market led? It may be that the market has pushed artists in this direction. If something is doing well, publishers will want more stuff like it of course.

Is there some correlation between our times and the fifties that leads people to this abstracted, flat, design led style? To the distance these styles keep the viewer from their subject? The fifties seems to have been a time when Modern was seen as good. Now in our more pessimistic times are we nostalgic about that idea and view of The Modern?

Are things so tough and uncertain that we want to stand a safe distance from the world, especially the world we present to our kids? I'm not any kind of psychologist so I don't know the answer to these questions, but I find the idea interesting.

What I do know is that I for one am getting bored sick of it. It's the illustration world's equivalent of all those young men with big beards, shaved sides of heads and plaid/check shirts ;-) That's getting really old too.

Talking of 'old', put the word 'grumpy' and 'man' in there too and you've defined me absolutely. . .

So as a card carrying Grumpy Old Man confronted by this Fifties obsession, I will say, as I've heard Americans say, 'Stick a fork in it and turn it over, it's done!'

Published on May 10, 2015 00:00

May 5, 2015

The Tiger Who We All Wish Would Come To Tea With Us, by Pippa Goodhart

Last Saturday I had a treat. I went to hear Judith Kerr talking about her work in Cambridge Union. Judith Kerr is a hero of mine for sharing her remarkable child refugee life with us all in her 'When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit' series of books, for her wonderful picture books, and just for being such an inspiring and nice person. Still publishing picture books now, in her nineties, she's a role model! But what I wanted to hear about most of all was her first, and I think, her best picture book of them all - The Tiger Who Came To Tea.

Judith and small daughter used to get ‘terribly bored’. So she made up bedtime stories. Judith felt that some of her other stories were at least as good as The Tiger One, but her daughter insisted on that Tiger One more than any other. "Talk the tiger' is what she would demand. One can imagine how such repeated tellings honed the wording of the story to perfection.

It was only once her daughter, Tacy, and the son who came later, were both at school ‘and staying there for their dinners’ that Judith had time for her own creative work once more, and she began that with the tiger story she knew so well. That was in 1966.

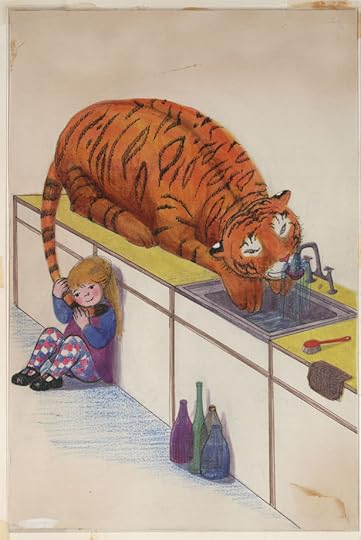

The prospective publisher liked the story, but questioned ‘how realistic’ it was that the tiger drank from a tap. Anyone with a cat knows that they do drink from taps, certainly more than they knock on front doors! And the glory of that drinking moment is that the Tiger ‘drank all the water in the tap’. I think that's the moment in the story we all remember the most. Incidentally, I couldn’t resist a little homage to that moment in one of my Winnie the Witch stories (written under the fake name of Laura Owen). When Winnie gets a new kitten, much to Wilbur’s annoyance, in a story in ‘Winnie The Bold’, it’s a tiger cub she’s got by mistake, rather than a kitten. That tiger causes havoc, eating everything in the larder and the fridge, and then, of course, drinking all the water in the tap. I’m so glad that Judith held strong and kept that tap-drinking!

The other problem perceived by the publishers was with one aspect of Judith’s artwork. ‘And they were quite right,’ said Judith. She had modelled the father figure on her husband, but he looked very different in different spreads. So she tried to get him to sit for her properly so that she could get the images right, but he was too busy … so she used an out of work actor friend instead, and, she says, that you can see that Daddy is distinctly ‘different’ on different pages. I’d never noticed that, but now I've gone back to look, I do see it!

Michael Rosen has a theory that the tiger knocking at the door, then coming in and helping itself to everything, represents the Gestapo who were doing their worst in the Germany that the Kerr family fled as the Nazis came to full power. But Judith Kerr says that’s quite wrong. The story grew the way it did because she and her daughter got bored with just each other for company whilst ‘Daddy’ was at work. They used to long for somebody to come and visit, and so that’s why the story grew out of a visitor coming to tea. Why a tiger? Simply because they had been to the zoo together, and both fallen in love with the tiger they saw there. She says they hadn’t at all contemplated how dangerous a tiger might be; just that they were so very beautiful, and they made you want to stroke that wonderful orange fur. So to have a tiger visiting, and letting you lean against its orange fur strength and warmth wasn’t a scary prospect at all. It was wonderful. I doubt any read it as a scary story. And, besides, the tiger is so very polite, he’s not at all a nasty intruder!

But that’s one of the beauties of stories, and especially those which are simply told. They leave room for you to bring your own interpretation to them. They become your story, individual to each one of us because we each ‘read’ and complete the story in our own unique way.

Published on May 05, 2015 00:00

April 30, 2015

Martin Salisbury discusses five great picture books

We're delighted to have this guest blog from Professor Martin Salisbury, course leader for the prestigious MA course in Children's Book Illustration run by Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge. An illustrator himself, Martin has written a number of important books about picture books for children and here he looks at five great picture books.

HansiBy Ludwig Bemelmans

Published by The Viking Press,

Published by The Viking Press,

New York, 1934Though best known for his subsequent, hugely popular Madeline books, of which there were five, Bemelmans’ first picturebook was this clearly semi-autobiographical tale of a childhood holiday in the Tyrol. Hansi is packed by his mother onto a little train and journeys up into the mountains where he stays with Uncle Herman, Aunt Amelie and their daughter, cousin Lieserl for the Christmas holidays. Various adventures are described through words and pictures in a generously sized format with alternating colour and black and white pages.

Born in 1898, the author had experienced a troubled upbringing in what was then Austrian territory (now Italian) and was sent to the United States at the age of eighteen to work in the hotel industry, eventually opening his own restaurant. This first venture into writing and illustrating came at the suggestion of friends and was well received by reviewers. It marked the beginning of a successful career as a humorist, novelist and artist. His work was characterized by an idiosyncratic, occasionally sentimental approach to the anecdotal.

There is far more text here than would be found in a modern picturebook. It falls somewhere between an illustrated book and what we now think of as a picturebook, with several beautiful double page spread illustrations in colour. Hansi was printed in the United States. No further details are given about the printing but it is clearly produced autolithographically. Bemelmans presumably would have needed to acquaint himself with this process, producing separations for each colour directly onto the plate and in places overlaying colours to create further hues, thereby maximizing the potential of the process. He appears to have used both lithographic crayon and inks. The first edition was issued with a dust jacket. Bemelmens’ extremely limited, at times appalling, draftsmanship is somehow always surmounted by the exuberance and charm of his vision.

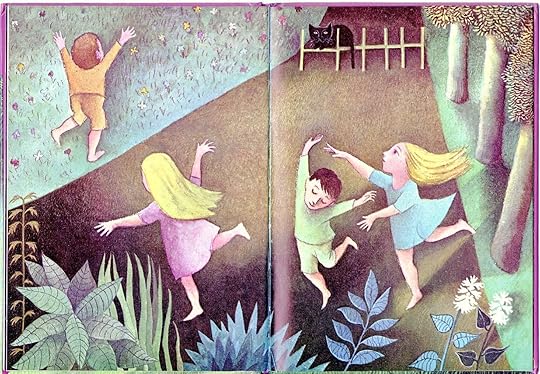

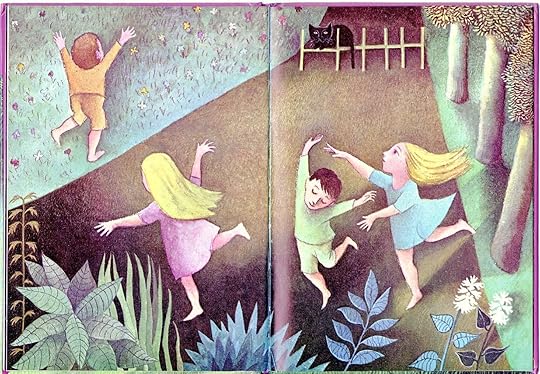

The Moon Jumpers

By Janice May Udry

Pictures by Maurice Sendek

Published by Harper & Row Inc.,

Published by Harper & Row Inc.,

New York, 1959This copy, 1st UK edition

(The Bodley Head, 1979)One of Sendak’s less well-known titles, this is a book that finds the great master in lyrical, sensual mode. Udry’s richly evocative text tells of a sultry, moonlit summer night, from the perspective of a group of children, out playing before bedtime. Sendak’s images give an almost pagan, ritualistic layer to the book as he uses heavily opaque paint to create formalized shapes of trees, buildings and children in intense moonlight. Using an almost pointillist technique, the artist eschews representational interest in architecture or flora in order to create a primitive, Rousseauesque atmosphere. The children seem to float and dance ritualistically across the pages in an operatic performance, brought to a close only by the call from the house: Mother calls from the door, “Children, oh children.” But we’re not children, we’re the Moon Jumpers!“It’s time,” she says.

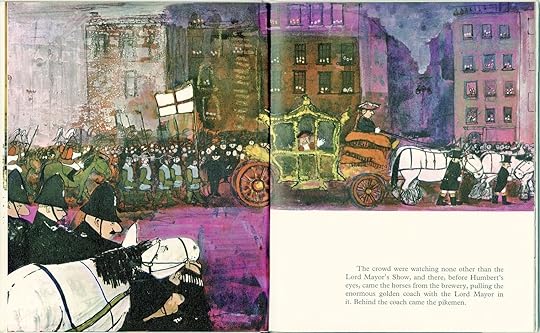

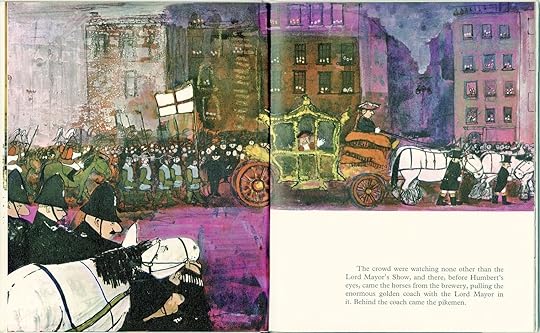

Humbert

By John Burningham

Published by Jonathan Cape, London, 1965

Published by Jonathan Cape, London, 1965

One of the greatest picturebook innovators of his generation, Burningham has consistently pushed at the boundaries of the medium with works such as Grandpa and Come Away from the Water Shirley. His precocious, Greenaway Medal-winning debut, Borka: The Adventures of a Goose with no Feathers, which was published in 1963, just over three years after receiving his diploma from the Central School of Art in London, gave notice of a unique talent that was emerging at a key time for illustration and in particular the picturebook. The development of new methods of lithographic printing and the vision of important figures in UK publishing such as Tom Maschler at Jonathan Cape and Mabel George at Oxford University Press helped initiate a ‘great leap forward’ in expressive picturebook art.

Humbert was Burningham’s fourth picturebook in these early post art school years. The book tells of a humble working horse in London whose owner trundles him daily through the city, collecting scrap onto his cart. One day, the Lord Mayor’s parade comes by and Humbert leaps into action to save the day as the mayor’s grand coach breaks down. More than anything though, the book is a visual celebration of London, a tour through the deep browns of dirty Victorian buildings and the heavy, smog laden nights, lit by a yellow moon.

Doctor De Soto

By William Steig

Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

New York, 1982Steig died in 2003 at the age of 95 after an illustrious career as a humourist, writer and illustrator. He did not begin making picturebooks until into he was into his sixties after working for many years as a cartoonist. Having managed to sell his cartoons at a very early age and become the family breadwinner, he went on to produce over 1600 drawings and 117 covers for the New Yorker magazine alone, characterized by his a highly distinctive, sardonic sense of humour. Of his children’s books, it is Shrek! that has become the most widely known in recent years, thanks to the success of the Hollywood film. Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (Simon & Schuster, 1969), the Caldecott Medal winning story of Sylvester’s the donkey’s discovery of a magic pebble that can make wishes come true has also become a Twentieth Century classic. It also caused some controversy due to the casting of pigs as police, a derogatory association that was particularly prevalent in the hippy era. Although Steig insisted no offence had been intended, the book was banned in some places.

As with all of Steig’s books, Doctor De Soto is firmly underpinned by a profound and meaningful narrative yet delivered with an easy lightness of touch, and great humour. A fox is suffering from acute toothache and begs the dentists, who happen to be mice, to remove the painful tooth. Despite their stated policy of ‘Cats and other dangerous animals not accepted for treatment’, the mice take pity on him and perform an extraction. Throughout the story, the fox is faced with the dilemma of whether or not to eat the mice after his dental surgery is complete. Steig’s text is hilariously matter of fact: “On his way home, he wondered if it would be shabby of him to eat the De Sotos when the job was done.”

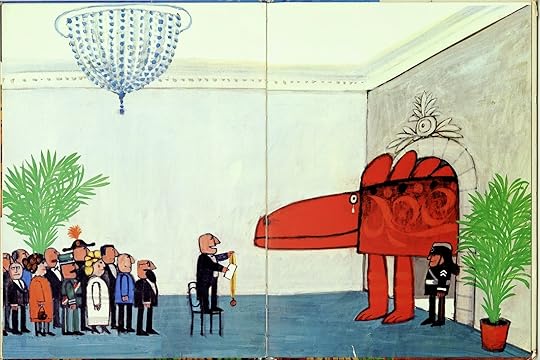

The Monster from Half-way to Nowhere

By Max Velthuÿs

Published by Nord-Sud Verlag, Mönchaltorf,

Published by Nord-Sud Verlag, Mönchaltorf,

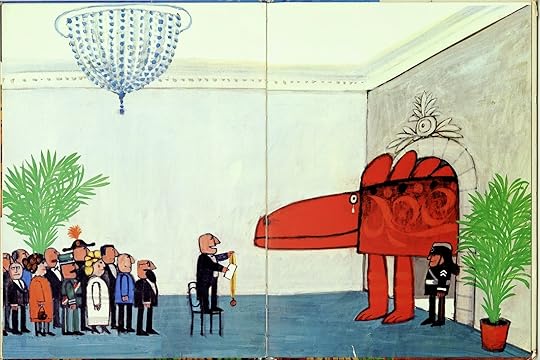

Switzerland, 1973

This copy: 1stUK edition, A&C Black, London, 1974Born in The Hague in 1923, Max Velthuÿs studied painting and graphic design at the Academie voor Beeldende Kunsten (Academy of the Visual Arts), before working for some time as a graphic ‘all-rounder, designing for advertising, TV and film. He came relatively late to picturebook making but found great success with the Frog books, beginning with Frog in Love, which was championed by the legendary Klaus Flugge at Andersen Press. Flugge went on to publish numerous subsequent tiles in the series. Velthuÿs’s Frog books are characterized by a graphic economy and an ability to address complex existential themes in an elegant understated manner, always stressing the innate nobility of human kindness.

The Monster from Half-way to Nowhere was one of the artist’s earlier picturebooks but already displays this lightness of touch and quietly philosophical approach. The page designs are masterful in their use of space and distribution of weight and colour. A fire-breathing monster arrives in a village to the consternation of the inhabitants, whose firemen immediately douse him with water. They try to put him to work as a military weapon but his natural good nature prevents him from wishing harm on anyone. Eventually he harnesses his fire to the newly built power station, providing electricity to the village.

Max Velthuÿs received the Hans Christian Andersen award for his contribution to children’s literature in 2004, a year before his death.

A discussion on further great picture books can be found in Martin Salisbury's 100 Great Picture Books, published by Laurence King in April 2015.

A discussion on further great picture books can be found in Martin Salisbury's 100 Great Picture Books, published by Laurence King in April 2015.

We wonder what you think of the intriguing selections? What books would be in your personal top three?

HansiBy Ludwig Bemelmans

Published by The Viking Press,

Published by The Viking Press, New York, 1934Though best known for his subsequent, hugely popular Madeline books, of which there were five, Bemelmans’ first picturebook was this clearly semi-autobiographical tale of a childhood holiday in the Tyrol. Hansi is packed by his mother onto a little train and journeys up into the mountains where he stays with Uncle Herman, Aunt Amelie and their daughter, cousin Lieserl for the Christmas holidays. Various adventures are described through words and pictures in a generously sized format with alternating colour and black and white pages.

Born in 1898, the author had experienced a troubled upbringing in what was then Austrian territory (now Italian) and was sent to the United States at the age of eighteen to work in the hotel industry, eventually opening his own restaurant. This first venture into writing and illustrating came at the suggestion of friends and was well received by reviewers. It marked the beginning of a successful career as a humorist, novelist and artist. His work was characterized by an idiosyncratic, occasionally sentimental approach to the anecdotal.

There is far more text here than would be found in a modern picturebook. It falls somewhere between an illustrated book and what we now think of as a picturebook, with several beautiful double page spread illustrations in colour. Hansi was printed in the United States. No further details are given about the printing but it is clearly produced autolithographically. Bemelmans presumably would have needed to acquaint himself with this process, producing separations for each colour directly onto the plate and in places overlaying colours to create further hues, thereby maximizing the potential of the process. He appears to have used both lithographic crayon and inks. The first edition was issued with a dust jacket. Bemelmens’ extremely limited, at times appalling, draftsmanship is somehow always surmounted by the exuberance and charm of his vision.

The Moon Jumpers

By Janice May Udry

Pictures by Maurice Sendek

Published by Harper & Row Inc.,

Published by Harper & Row Inc., New York, 1959This copy, 1st UK edition

(The Bodley Head, 1979)One of Sendak’s less well-known titles, this is a book that finds the great master in lyrical, sensual mode. Udry’s richly evocative text tells of a sultry, moonlit summer night, from the perspective of a group of children, out playing before bedtime. Sendak’s images give an almost pagan, ritualistic layer to the book as he uses heavily opaque paint to create formalized shapes of trees, buildings and children in intense moonlight. Using an almost pointillist technique, the artist eschews representational interest in architecture or flora in order to create a primitive, Rousseauesque atmosphere. The children seem to float and dance ritualistically across the pages in an operatic performance, brought to a close only by the call from the house: Mother calls from the door, “Children, oh children.” But we’re not children, we’re the Moon Jumpers!“It’s time,” she says.

Humbert

By John Burningham

Published by Jonathan Cape, London, 1965

Published by Jonathan Cape, London, 1965One of the greatest picturebook innovators of his generation, Burningham has consistently pushed at the boundaries of the medium with works such as Grandpa and Come Away from the Water Shirley. His precocious, Greenaway Medal-winning debut, Borka: The Adventures of a Goose with no Feathers, which was published in 1963, just over three years after receiving his diploma from the Central School of Art in London, gave notice of a unique talent that was emerging at a key time for illustration and in particular the picturebook. The development of new methods of lithographic printing and the vision of important figures in UK publishing such as Tom Maschler at Jonathan Cape and Mabel George at Oxford University Press helped initiate a ‘great leap forward’ in expressive picturebook art.

Humbert was Burningham’s fourth picturebook in these early post art school years. The book tells of a humble working horse in London whose owner trundles him daily through the city, collecting scrap onto his cart. One day, the Lord Mayor’s parade comes by and Humbert leaps into action to save the day as the mayor’s grand coach breaks down. More than anything though, the book is a visual celebration of London, a tour through the deep browns of dirty Victorian buildings and the heavy, smog laden nights, lit by a yellow moon.

Doctor De Soto

By William Steig

Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux,

Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 1982Steig died in 2003 at the age of 95 after an illustrious career as a humourist, writer and illustrator. He did not begin making picturebooks until into he was into his sixties after working for many years as a cartoonist. Having managed to sell his cartoons at a very early age and become the family breadwinner, he went on to produce over 1600 drawings and 117 covers for the New Yorker magazine alone, characterized by his a highly distinctive, sardonic sense of humour. Of his children’s books, it is Shrek! that has become the most widely known in recent years, thanks to the success of the Hollywood film. Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (Simon & Schuster, 1969), the Caldecott Medal winning story of Sylvester’s the donkey’s discovery of a magic pebble that can make wishes come true has also become a Twentieth Century classic. It also caused some controversy due to the casting of pigs as police, a derogatory association that was particularly prevalent in the hippy era. Although Steig insisted no offence had been intended, the book was banned in some places.

As with all of Steig’s books, Doctor De Soto is firmly underpinned by a profound and meaningful narrative yet delivered with an easy lightness of touch, and great humour. A fox is suffering from acute toothache and begs the dentists, who happen to be mice, to remove the painful tooth. Despite their stated policy of ‘Cats and other dangerous animals not accepted for treatment’, the mice take pity on him and perform an extraction. Throughout the story, the fox is faced with the dilemma of whether or not to eat the mice after his dental surgery is complete. Steig’s text is hilariously matter of fact: “On his way home, he wondered if it would be shabby of him to eat the De Sotos when the job was done.”

The Monster from Half-way to Nowhere

By Max Velthuÿs

Published by Nord-Sud Verlag, Mönchaltorf,

Published by Nord-Sud Verlag, Mönchaltorf, Switzerland, 1973

This copy: 1stUK edition, A&C Black, London, 1974Born in The Hague in 1923, Max Velthuÿs studied painting and graphic design at the Academie voor Beeldende Kunsten (Academy of the Visual Arts), before working for some time as a graphic ‘all-rounder, designing for advertising, TV and film. He came relatively late to picturebook making but found great success with the Frog books, beginning with Frog in Love, which was championed by the legendary Klaus Flugge at Andersen Press. Flugge went on to publish numerous subsequent tiles in the series. Velthuÿs’s Frog books are characterized by a graphic economy and an ability to address complex existential themes in an elegant understated manner, always stressing the innate nobility of human kindness.

The Monster from Half-way to Nowhere was one of the artist’s earlier picturebooks but already displays this lightness of touch and quietly philosophical approach. The page designs are masterful in their use of space and distribution of weight and colour. A fire-breathing monster arrives in a village to the consternation of the inhabitants, whose firemen immediately douse him with water. They try to put him to work as a military weapon but his natural good nature prevents him from wishing harm on anyone. Eventually he harnesses his fire to the newly built power station, providing electricity to the village.

Max Velthuÿs received the Hans Christian Andersen award for his contribution to children’s literature in 2004, a year before his death.

A discussion on further great picture books can be found in Martin Salisbury's 100 Great Picture Books, published by Laurence King in April 2015.

A discussion on further great picture books can be found in Martin Salisbury's 100 Great Picture Books, published by Laurence King in April 2015.We wonder what you think of the intriguing selections? What books would be in your personal top three?

Published on April 30, 2015 00:00

April 24, 2015

Patience, patience… by Jane Clarke

Like many children's authors, I've been visiting a lot of schools recently. In a couple of schools, we've even had the time to make books. It's made me realise that when I'm writing a picture book text, I have a lot in common with the kids. It's exciting when your head is fizzing with ideas that might make a book!

Inspired? Fantastic! But now you need to make it into a story and write it down….It's hard to get your thoughts down on paper so that someone else can read and understand them.

The danger is that some of the fizz evaporates somewhere along the way between mind maps, story plans, and writing, so it really helps when people are enthusiastic about your ideas.

Thanks to all the fantastic, enthusiastic and dedicated teachers I worked with.

It's hard to be patient and polish up your work.

Oh yes. But it's worth taking time so that the finished book is as good as it can be.

Congratulations to all the children who made wonderful books.

Making a book is a l-ooo-ooo-ooo-ng process. When asked to guess how long one of my picture book texts takes to write, edit, be illustrated and appear in the shops, children will often guess 'a week.' When I tell them it takes at least two and a half years, and sometimes up to five years, they think that's an eternity.

Sometimes if feels like an eternity, too! But the fizz when you get a new idea you just have to put down on paper somehow makes it all worthwhile, especially if that idea turns into a book!

Jane's impatiently awaiting the publication of 4 toddler board books, 3 picture books and 2 more books in her Dr KittyCat series and has recently been lured onto Twitter@JaneClarkeWrite https://www.facebook.com/JaneClarkeChildrensAuthor

Published on April 24, 2015 23:30

April 20, 2015

Do you want to earn more money writing? Moira Butterfield

I expect the answer to that title is yes. Nicola Morgan recently wrote a great blog about it, with practical and positive suggestions, and I’ve put a link to that blog at the bottom of this one. One of her suggestions is the possibility of writing more by taking on paid fee work. That’s what I do and have done for many years. For picture book authors there are opportunities to do this in board books and early-years educational books. Some of you will be old hands at doing this but for those who like the idea but haven’t tried it, or are new to writing as a career, here are some points I thought might be helpful.

It’s a craft, like journalism

Writing paid fee work is not the same as writing your own stuff with royalties promised down the line. It’s a different discipline. It’s more akin to journalism because you are commissioned by an editor to provide what they want, and your work can be altered.

It has serious deadlines

Fee work has set schedules, often very tight. They aren’t to be messed with. You can’t decide to add on time because you needed to do this or that away from work, and you can’t plead writer’s block. I was once an editor who commissioned fee work, and if someone let me down schedule-wise I never commissioned them again because I had to carry the can for it. If I ever missed a print date the sales team and the production team would kick my boss who would kick me twice as hard because it would cost my company money. If you can’t, hand on heart, write under pressure to meet a date, you shouldn’t take on fee work.

Having said that, suggested fee work schedules can be ridiculous. Say no to those. They bring only stress and bitterness. (Ask if there is more time before you say no, though, just in case).

Fees – don’t roll over and do it for nothing Fees are tight and getting tighter, and some publishers try to take the mickey. There’s no pot of gold. For an insight into the money side, and into working with fee-paying editors, read the excellent ‘tell it like it is’ blog by Anne Rooney - Again I've added a link at the bottom of this blog.

To work out if a fee is fair, get out your calculator and punch in the hours you think you will need. Multiply this by your hourly rate (you don’t need to tell the publisher what that is, by the way. It’s your business, no theirs.)

You sign away rights You will be asked to sign away rights in flat fee work. There’s some excellent material about this on the UK NUJ website, also with a useful guide to fees being paid in the UK. If there are similar sites in other countries, and you know of them, please do let us know about them in the comments section.

http://www.londonfreelance.org/feesguide/index.php?language=en&country=UK§ion=Print+media&subsect=Books&page=Advice

You don’t get the last sayYour editor may ask for changes. The sales team may ask for changes. You can point out why you think they’re wrong but in the end they get to do what they want. If you hate what they’ve done, you do have the option of making sure your name does not appear on the work.

You may wish to use a pseudonym for fee work, and a different name for your own work. I'm hoping to do this myself in the near future for fiction-writing.

There is often hassle

There is often hassle because fee-based projects sometimes evolve in-house as you’re writing. You need to be professional on these occasions, however unreasonable demands may be. It’s sometimes very tempting to shout ‘stuff it’ but never ever do. It’s always better to have dignity on a professional situation.

Here’s a little taste of things that have happened to me in just the last couple of months. It’s normal for fee work.

* Page counts were changed more than once. It’s ok. I can handle it. * Foreign publishers buying rights from my UK publisher demanded changes at a late stage (this has happened twice in the last 2 months). In both cases it turned out not to be too onerous, just annoying.* An incorrect brief was sent to me by an editor, and so a big bookplan had to be redone. It’s ok. We all make mistakes, and I hadn’t begun writing.* One editor was unpleasant to work with. Some people need to be avoided and you tend to find out the hard way, but that's the same in most professions I guess.

You have to stay calm and did what you can to move the job on, within reason. If you take on fee work, be prepare to handle a bit of messing about (no need to roll over, but best not to throw hissy fits, however deserved).

You may work with lots of editors, some great and some not. When people ask me ‘who’s your publisher’ the answer is ‘many’. Some are great – polite, focused and creative – and I’d do anything for them. Some are not. You’re likely to come across more of both types if you work with more than one company.

Publishing parties, book tours and festival appearances organized by your publisher. Forget it. Doesn’t happen. You’ll even have to check they got your name right on Amazon, and the date your book is published. However, you can do your own school tours and earn money on the back of the books you’ve done, royalties or not. See Nicola Morgan’s blog for advice on that. And you can get PLR for library-borrowing in the UK, which over time can really make a difference to the fee. Other countries have their own schemes for this.

A non-picture book I wrote this year. A lot of fun to do.

A non-picture book I wrote this year. A lot of fun to do. Time to do your own writing? Er…. Doing fee work sucks up your time and your creative energy. So if you take on lots, don’t expect to have much time left for your own projects. You need to find a balance, and I haven’t, which is why I’m manically writing this blog at the last minute. I’ve just counted up the books I wrote from April 2014 to April 2015 and even I am shocked and a bit too embarrassed to write the number. Some are history books, some are sets of board books for under-5s. There’s part of a poetry book, a practical nature guide, a body book and a book on the weather... That doesn’t include the editing work I’ve done on other people’s projects, and the development work I’ve done. It’s no wonder I’m struggling to finish the novel I’ve been trying to write. Just bear this in mind before you plunge into fee work.

I regularly write educational history.

I regularly write educational history. You get to have a lot of funI get some fantastic projects offered to me that I really enjoy. This last year I’ve discovered the incredible worlds of the Stone Age and the Bronze Age – and now I’m really hooked on them. I’ve been offered a poetry commission for the very first time. I got to write a guide to Barcelona. I’m currently writing a series on children around the world, and loving it (though the schedule is nuts).

I contributed to this new poetry

I contributed to this new poetry anthology, published by Collins

…and I’ve had a picture book accepted, so I can still hold my head up (just) on this marvellous blogsite. Now all I need to do is find a way to stay awake through the night to get that novel done….

Would love to hear your views/experiences on taking fee work, and ask me any questions you want. It's not for everyone, that's for sure.

Here is Nicola Morgan's extremely helpful blog on earning more money:

http://awfullybigblogadventure.blogspot.co.uk/2015/03/how-writers-can-earn-more-by-nicola.html

Here is Anne Rooney's blog on working with editors and costing a project:

http://www.stroppyauthor.com/2015_02_01_archive.html

Moira Butterfield www.moirabutterfield.com

@moiraworld

Published on April 20, 2015 00:32

April 15, 2015

Perfection in Picturebook - the art of Charlotte Zolotow, by Malachy Doyle

I want to write about perfect picture books. I want to write about Charlotte Zolotow.

Charlotte was born nearly 100 years ago, on June 26 1915. She almost made it to a hundred, but on November 19 2013, at the grand old age of 98, she died.

I was looking through my collection of picture books the other day, searching for ones that come closest to my idea of perfection - that intangible quality that we as writers are always trying to achieve, but always find slipping out of reach. I need to remind myself, every now and again, that perfection is achievable. I need to remind myself what it looks like.

I came across a few: Frog and the Birdsong by Max Velthuijs, Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present by Charlotte Zolotow (illustrated by the incomparable Maurice Sendak), Dogger, The Tiger who Came to Tea, Where the Wild Things Are, Owl Babies, Something Else...

And then there she was again: Charlotte Zolotow - The Summer Night.

How did she do it? How did she write two of my all-time favourite picture books, two of the books that somehow found their way onto my bookshelf long before I became a writer, two that were read, over and over again to my own three children as they grew. I knew nothing of perfection then. I knew little about picture books. Just that these two stories were a joy to read, over and over. And that my children loved them.

The Summer Night was originally published in 1958, under the title 'The Night When Mother Was Away'. But the copy my family know and love was a re-issue, re-titled and with new illustrations, this time by Ben Schecter. When I look at them now the illustrations seem sketchy, almost amateurish - but they work - they simply work. Soft charcoal drawings, so it's basically black and white, but with pink and blue washes, almost like a child has coloured them in. They have a simplicity, an unfussy warmth, a total gentleness that perfectly captures the tone, the setting, the character (and characters) of the writing. And what writing!

The little girl's father took care of her all day. In the evening he bathed her and put her to bed. but the little girl wasn't sleepy. 'I'm thirsty,' she said. He brought her a cup of water.

So simple. So effective. He brings her an apple, he opens the window...

She looked out into the darkness. The sky was full of stars. The little girl's eyes were bright as the stars, and her father could understand why on this soft summer night she wasn't sleepy.

He carries her downstairs:

the gold clock on the mantelpiece seemed to say, night-time-night-time-night-time

He reads her a story, but she still isn't sleepy, so...

He sat down on the piano bench and the little girl leaned against him and he played some soft night-time music, so gently the sounds hung like little birds in the air, warm and feathery and sweet.

(A thirty-seven word sentence! I'd never dream of writing a thirty-seven word sentence in a picture book, but it works. It so works!)

But the little girl still isn't sleepy, so he takes her outside.

The screen door closed behind them like a whisper in the night.

They sit by the pond. Two rabbits stare at them

before they bounded into the bushes and were gone.

White ducks are sleeping on the opposite bank.

The moon reflected in the pond, seemed so close the little girl felt she could reach into the water and hold it in her hands.

The father throws a pebble and they watch the circles rippling out and out in the black water...

They head back to the house, hearing the cat's bell tinkle, an owl hooting, before they have warm milk and bread and butter with brown sugar.

Sugar on bread - just imagine!

Now the father saw that the little girl's eyes were dreamy and sleepy at last.

So he carried her upstairs and put her to bed again. He bent down to kiss her and the little girl kissed him back.

Outside the night owl cried again. Whoooooo Whooooooooooo WHOOOoooooooooooooo....

But this time the little girl didn't hear. She was fast asleep.

And so were my children - many, many times.

Sheer perfection in 700-ish words. (Despite a thirty seven word sentence, sugar on your bread, and not even bothering to name your lead characters!)

Charlotte wrote lots of other wonderful books but, as if that wasn't enough, she was also a revered children's book editor. I'll leave you with a great quote from her, one you might choose (or not) to hold on to as you strive towards perfection.

"Being both a writer and editor affects different expressions of the same personality. Writers must shut out everyone else while they write. They must forget outside suggestions, or the temptation to follow suggestions separate from their own visions.

Editors must resist the desire to insert their own idea of how and where the story goes. They must resist the temptation to offer their own words as a solution when something is weak; instead they should alert the writer to this weakness, so that if the writer agrees, she may solve the problem in her own words and way."

Malachy's latest picture book:

Malachy's latest picture book:

The Nose that Knows (Parragon Books, illustrated by Barroux)

Charlotte was born nearly 100 years ago, on June 26 1915. She almost made it to a hundred, but on November 19 2013, at the grand old age of 98, she died.

I was looking through my collection of picture books the other day, searching for ones that come closest to my idea of perfection - that intangible quality that we as writers are always trying to achieve, but always find slipping out of reach. I need to remind myself, every now and again, that perfection is achievable. I need to remind myself what it looks like.

I came across a few: Frog and the Birdsong by Max Velthuijs, Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present by Charlotte Zolotow (illustrated by the incomparable Maurice Sendak), Dogger, The Tiger who Came to Tea, Where the Wild Things Are, Owl Babies, Something Else...

And then there she was again: Charlotte Zolotow - The Summer Night.

How did she do it? How did she write two of my all-time favourite picture books, two of the books that somehow found their way onto my bookshelf long before I became a writer, two that were read, over and over again to my own three children as they grew. I knew nothing of perfection then. I knew little about picture books. Just that these two stories were a joy to read, over and over. And that my children loved them.

The Summer Night was originally published in 1958, under the title 'The Night When Mother Was Away'. But the copy my family know and love was a re-issue, re-titled and with new illustrations, this time by Ben Schecter. When I look at them now the illustrations seem sketchy, almost amateurish - but they work - they simply work. Soft charcoal drawings, so it's basically black and white, but with pink and blue washes, almost like a child has coloured them in. They have a simplicity, an unfussy warmth, a total gentleness that perfectly captures the tone, the setting, the character (and characters) of the writing. And what writing!

The little girl's father took care of her all day. In the evening he bathed her and put her to bed. but the little girl wasn't sleepy. 'I'm thirsty,' she said. He brought her a cup of water.

So simple. So effective. He brings her an apple, he opens the window...

She looked out into the darkness. The sky was full of stars. The little girl's eyes were bright as the stars, and her father could understand why on this soft summer night she wasn't sleepy.

He carries her downstairs:

the gold clock on the mantelpiece seemed to say, night-time-night-time-night-time

He reads her a story, but she still isn't sleepy, so...

He sat down on the piano bench and the little girl leaned against him and he played some soft night-time music, so gently the sounds hung like little birds in the air, warm and feathery and sweet.

(A thirty-seven word sentence! I'd never dream of writing a thirty-seven word sentence in a picture book, but it works. It so works!)

But the little girl still isn't sleepy, so he takes her outside.

The screen door closed behind them like a whisper in the night.

They sit by the pond. Two rabbits stare at them

before they bounded into the bushes and were gone.

White ducks are sleeping on the opposite bank.

The moon reflected in the pond, seemed so close the little girl felt she could reach into the water and hold it in her hands.

The father throws a pebble and they watch the circles rippling out and out in the black water...

They head back to the house, hearing the cat's bell tinkle, an owl hooting, before they have warm milk and bread and butter with brown sugar.

Sugar on bread - just imagine!

Now the father saw that the little girl's eyes were dreamy and sleepy at last.

So he carried her upstairs and put her to bed again. He bent down to kiss her and the little girl kissed him back.

Outside the night owl cried again. Whoooooo Whooooooooooo WHOOOoooooooooooooo....

But this time the little girl didn't hear. She was fast asleep.

And so were my children - many, many times.

Sheer perfection in 700-ish words. (Despite a thirty seven word sentence, sugar on your bread, and not even bothering to name your lead characters!)

Charlotte wrote lots of other wonderful books but, as if that wasn't enough, she was also a revered children's book editor. I'll leave you with a great quote from her, one you might choose (or not) to hold on to as you strive towards perfection.

"Being both a writer and editor affects different expressions of the same personality. Writers must shut out everyone else while they write. They must forget outside suggestions, or the temptation to follow suggestions separate from their own visions.

Editors must resist the desire to insert their own idea of how and where the story goes. They must resist the temptation to offer their own words as a solution when something is weak; instead they should alert the writer to this weakness, so that if the writer agrees, she may solve the problem in her own words and way."

Malachy's latest picture book:

Malachy's latest picture book: The Nose that Knows (Parragon Books, illustrated by Barroux)

Published on April 15, 2015 00:01

April 10, 2015

Bringing the picture book retreat experience back home by Juliet Clare Bell

I’m just back from a wonderful week away writing in the middle of nowhere in Yorkshire.

(The only downside, I had a Kate Bush ear-worm all week...)

It was fantastic for recharging my batteries and writing, but possibly the best part of it was time and head space to think about writing and how I can change what I do at home in order to write better.Here are some things I’ve learned…

[1] ComputersUntil now, when I’ve written, I’ve always used a computer. It’s my default. If I’m going to work, I open up my computer. I type faster than I write and I’ve got really used to writing straight onto computer. But for a picture book, with very few words, how much does that actually matter? After spending way less time even within sight of a computer on retreat, my default when working on picture books from now will be with my laptop out of sight. I’ll use it when I need it.

[2] FacebookI had over a week without looking at Facebook. Did I miss the thing that I feel compelled to check many times a day whilst writing at home? Not one bit. Because the vast majority of my Facebook friends are children’s writers and all of the groups I’m in are children’s writing based, I’ve tried to trick myself in the past that there’s more of an element of work about it than there is. So, I have now banned myself from Facebook during the day, during the week. I’ve given myself permission to check it in the evening for a maximum of half an hour if I really want to. But since I’m way more drawn to it when I’m struggling with some writing and want a quick distraction, I think I may be about to have a much more casual relationship with Facebook.

[3] Writing big –and messyI love using lining paper to get ideas down onto but I can go months without doing it sometimes. Not any more. I bought rolls of wallpaper lining paper to the retreat –and I used it. Lots of it. It feels like such a happy, creative way to work.

One of the best uses I found for it was for ten-minute brainstorms, where you take an idea for a picture book and then just brainstorm –big- for ten minutes, setting a timer, and then stopping and moving onto the next one. It’s like speed-dating for ideas. You realise very quickly if you might be onto something. I’ve done it before with hour-long brainstorming sessions for each idea, but what I found on retreat was that I probably got almost as much out of a ten-minute session as an hour-long one, and certainly, it’s an easy, fun and -now even quicker!- way to work through all those hundreds of ideas (think of all those PiBoIdMo ideas generated every year!) that in my case at least, rarely go beyond the initial idea.

[4] Type 2 fun… My daughter has recently started referring to Type 2 fun to describe something that you’re really satisfied with after the event, but you don’t necessarily enjoy it wholeheartedly at the time. She was talking about an adventure course in a forest, high up. She really wanted to do it with her friends but doesn’t actually like heights –definitely Type 2 fun.

Whilst I was away, I decided to take apart the process of how I create a picture book and divide the stages into Type 1 and Type 2, with a view to seeing if I could make the process as fun as possible. It was really useful -and quite challenging…

Type 1 fun: the bits I enjoy when creating a picture book (at the moment):

Brainstorming -it provides instant visual gratification (since I don’t do the pictures, I have to get my visual gratification where I can!); it feels really creative; there's no censoring; it's empowering; messy; stress-free, and slightly magic (at the end of a short session, you’ve come up with loads of ideas that didn’t even exist just ten minutes before)

Research - (often only a small amount is needed in a fictional picture book, but I’ve needed to do loads more recently as I’ve done more non-fiction) it's fascinating; I learn loads; and there's the exciting challenge of getting it across in a really lyrical and accessible way

Structuring – turning the free and easy brainstorming into something that works within the many constraints of the picture book form

Questioning my characters –discovering their motivations; getting to know why they’d do certain things and how they feel about what’s happening. I am inherently nosy (I used to be a psychologist and I’m fascinated by people, including characters). Until now, this has often happened after the event, where I go back over drafts and ask those questions and discover new things about my story’s characters. Although I will still do that at a later time, I’m now incorporating it more into the structuring of the book)

Critiquing –I do a lot of critiquing of other people’s manuscripts, both professionally and as part of critique groups. It turns out I really enjoy critiquing my own manuscripts as if they were someone else’s. It’s very freeing. What I’ve also discovered works well for me is taking other people’s critiques of my manuscript, reading them carefully and then doing a full critique of my own manuscript. The points that fellow writers made which I really agreed with are all incorporated into my own critique, but in my own words

Making rhymes work well

Type 2 fun –the bits I’ve discovered I’m not enjoying so much at the moment

Starting the actual writing – for whatever reason, I’m finding this bit stressful at the moment.

Writing –although this challenges my notion of myself as a writer, when I thought about it carefully, I think that I’m not massively enjoying the writing part at the moment. When it all flows and it feels Zen-like, I love it, but too often at the moment, there isn’t that flow and it doesn’t feel so good. A fellow picture book writer and good friend of mine said last year that she doesn’t actually enjoy writing her picture books. I was shocked –she’s completely dedicated to it, and I thought that we were really different in that respect. But I think she was just being more self-aware than me, and just saying what it’s taken me an extra year or so to realise of myself.

Actually making the edits once I’ve done the self-critiquing

So what can I do to make the writing process a more enjoyable one based on those realisations?

I need to re-remember that writing is way more than the actual act of writing the words. I enjoy so many of the other parts of writing, and I want to maximise the Type 1 fun bits and minimise the Type 2 bits. So I can fully justify spending plenty of time brainstorming and structuring before I write a single word of the actual manuscript –and that’s still writing. And since I don’t like starting, I need to make the writing part of the first draft really quick. Where I can, I need to get a first really, really rough first draft done in a single sitting. That way, I only have to start once for each project. This doesn’t necessarily mean I’ll be completing a picture book more quickly, but it does mean that the bits I struggle to motivate myself to do are a much smaller part of the whole process.

And I haven’t written a rhyming manuscript for eighteen months, which I definitely need to rectify.

My decision to use a computer less means that I’m going to print out manuscripts more. In the last couple of years, I’ve written whole manuscripts through to final edits without once printing the story out. Now, I can do a lot of the final editing straight onto paper, which it turns out, is a nicer process (who knew?).

And actually, just getting on with it and doing it quickly means that I’ll get into better habits and some of those Type 2 activities may well move back over to Type 1 ones.

A writer friend of mine said recently “Writing doesn’t always look like writing”. It’s very true, but without having the option of Facebook during the day, more of the things I'm doing now that aren't physically writing are genuinely part of the "writing doesn't always look like writing" writing.

Use positive distractions. I know that I need to distract myself sometimes and Facebook has often been my distraction of choice, in the way that chocolate is my snack of choice if it’s in the house. But I know that I’m much better off having healthier snacks easily accessible and not having an unhealthy alternative available. My post-retreat healthy option distraction is a (non-story) book. I’m keeping it near me when I write, and if I really need a quick procrastinating dip into something, that’ll be it.

[5] More writing outside (Whoops, that last point was so long I forgot I was doing a list!)- I really enjoyed the opportunities I had to work outside –researching, brainstorming, structuring and actual physical writing by hand.

It wasn’t often warm enough to be stationery outside for long but when it was, I was out, even when I had to be in several jumpers, a coat, hat and scarf and woolly fingerless gloves…

I need to do that more. And now with less emphasis on my computer, I can –and will- do that.

[6] Make the most of the stillness. I loved it in the morning when I wrote before having spoken to anyone or listened to anything on the radio etc. I used to do this at home by getting up at 6am and getting an hour in before anyone woke up. And I’m determined to go back to that again, having reaped the benefits of the stillness of it on retreat.

[7] Recognise that this all happens in real life. I was able to go on retreat for a week but in real life, I have three amazing and highly distracting children who need to be loved, fed, played with and taken to, and collected from, school every day. I need to make all these changes within my real life and be more efficient whilst I’m working so that once they’re home, I’m theirs alone until they go to bed. More efficient includes using a separate (A4 hardback unlined) notebook for every project I do from now on, so I don’t lose any of my thoughts because they’re in one of twenty or thirty notebooks that are on the go at the same time.

I’m starting a reflection journal so I can work out what’s working well and what could work better. This is so useful for best practice, particularly with school visits, but I think it’ll be good for writing, too. And I think that keeping my computer out of view means that I can be much more present in work and life (and I hope it’ll help my children to grow up not thinking that on-line life is more interesting than real life).

And finally, I’ve found a way to recreate the retreat experience as closely as possible one day a week, when the children are not here. I will have a computer-free day where I don’t actually speak to anyone at all, in person, or on the phone or online from when I wake up until I pick the children up from school. No radio, no internet, no opening up a computer, no voices at all apart from my characters’.

I made a plan whilst I was away and it still looks completely doable now I’m back. I’m going to stick to it. I’m going to take more risks and make more mistakes, and though I’ll make myself do some Type 2 fun every day, I reckon there’s going to be an increasing amount of Type 1 fun on its way.

A story, brainstormed, structured and written as a really rough first draft, mostly outside, and not going near a computer until I'd handwritten THE END, and all in one day...

Thanks to fellow writers, Ali and Annie, for a fab week.

What about you and your writing? Which parts of the book creating process are currently Type 2 fun for you?

www.julietclarebell.com

(The only downside, I had a Kate Bush ear-worm all week...)

It was fantastic for recharging my batteries and writing, but possibly the best part of it was time and head space to think about writing and how I can change what I do at home in order to write better.Here are some things I’ve learned…

[1] ComputersUntil now, when I’ve written, I’ve always used a computer. It’s my default. If I’m going to work, I open up my computer. I type faster than I write and I’ve got really used to writing straight onto computer. But for a picture book, with very few words, how much does that actually matter? After spending way less time even within sight of a computer on retreat, my default when working on picture books from now will be with my laptop out of sight. I’ll use it when I need it.

[2] FacebookI had over a week without looking at Facebook. Did I miss the thing that I feel compelled to check many times a day whilst writing at home? Not one bit. Because the vast majority of my Facebook friends are children’s writers and all of the groups I’m in are children’s writing based, I’ve tried to trick myself in the past that there’s more of an element of work about it than there is. So, I have now banned myself from Facebook during the day, during the week. I’ve given myself permission to check it in the evening for a maximum of half an hour if I really want to. But since I’m way more drawn to it when I’m struggling with some writing and want a quick distraction, I think I may be about to have a much more casual relationship with Facebook.

[3] Writing big –and messyI love using lining paper to get ideas down onto but I can go months without doing it sometimes. Not any more. I bought rolls of wallpaper lining paper to the retreat –and I used it. Lots of it. It feels like such a happy, creative way to work.

One of the best uses I found for it was for ten-minute brainstorms, where you take an idea for a picture book and then just brainstorm –big- for ten minutes, setting a timer, and then stopping and moving onto the next one. It’s like speed-dating for ideas. You realise very quickly if you might be onto something. I’ve done it before with hour-long brainstorming sessions for each idea, but what I found on retreat was that I probably got almost as much out of a ten-minute session as an hour-long one, and certainly, it’s an easy, fun and -now even quicker!- way to work through all those hundreds of ideas (think of all those PiBoIdMo ideas generated every year!) that in my case at least, rarely go beyond the initial idea.

[4] Type 2 fun… My daughter has recently started referring to Type 2 fun to describe something that you’re really satisfied with after the event, but you don’t necessarily enjoy it wholeheartedly at the time. She was talking about an adventure course in a forest, high up. She really wanted to do it with her friends but doesn’t actually like heights –definitely Type 2 fun.

Whilst I was away, I decided to take apart the process of how I create a picture book and divide the stages into Type 1 and Type 2, with a view to seeing if I could make the process as fun as possible. It was really useful -and quite challenging…

Type 1 fun: the bits I enjoy when creating a picture book (at the moment):

Brainstorming -it provides instant visual gratification (since I don’t do the pictures, I have to get my visual gratification where I can!); it feels really creative; there's no censoring; it's empowering; messy; stress-free, and slightly magic (at the end of a short session, you’ve come up with loads of ideas that didn’t even exist just ten minutes before)

Research - (often only a small amount is needed in a fictional picture book, but I’ve needed to do loads more recently as I’ve done more non-fiction) it's fascinating; I learn loads; and there's the exciting challenge of getting it across in a really lyrical and accessible way

Structuring – turning the free and easy brainstorming into something that works within the many constraints of the picture book form

Questioning my characters –discovering their motivations; getting to know why they’d do certain things and how they feel about what’s happening. I am inherently nosy (I used to be a psychologist and I’m fascinated by people, including characters). Until now, this has often happened after the event, where I go back over drafts and ask those questions and discover new things about my story’s characters. Although I will still do that at a later time, I’m now incorporating it more into the structuring of the book)

Critiquing –I do a lot of critiquing of other people’s manuscripts, both professionally and as part of critique groups. It turns out I really enjoy critiquing my own manuscripts as if they were someone else’s. It’s very freeing. What I’ve also discovered works well for me is taking other people’s critiques of my manuscript, reading them carefully and then doing a full critique of my own manuscript. The points that fellow writers made which I really agreed with are all incorporated into my own critique, but in my own words

Making rhymes work well

Type 2 fun –the bits I’ve discovered I’m not enjoying so much at the moment

Starting the actual writing – for whatever reason, I’m finding this bit stressful at the moment.

Writing –although this challenges my notion of myself as a writer, when I thought about it carefully, I think that I’m not massively enjoying the writing part at the moment. When it all flows and it feels Zen-like, I love it, but too often at the moment, there isn’t that flow and it doesn’t feel so good. A fellow picture book writer and good friend of mine said last year that she doesn’t actually enjoy writing her picture books. I was shocked –she’s completely dedicated to it, and I thought that we were really different in that respect. But I think she was just being more self-aware than me, and just saying what it’s taken me an extra year or so to realise of myself.

Actually making the edits once I’ve done the self-critiquing

So what can I do to make the writing process a more enjoyable one based on those realisations?

I need to re-remember that writing is way more than the actual act of writing the words. I enjoy so many of the other parts of writing, and I want to maximise the Type 1 fun bits and minimise the Type 2 bits. So I can fully justify spending plenty of time brainstorming and structuring before I write a single word of the actual manuscript –and that’s still writing. And since I don’t like starting, I need to make the writing part of the first draft really quick. Where I can, I need to get a first really, really rough first draft done in a single sitting. That way, I only have to start once for each project. This doesn’t necessarily mean I’ll be completing a picture book more quickly, but it does mean that the bits I struggle to motivate myself to do are a much smaller part of the whole process.

And I haven’t written a rhyming manuscript for eighteen months, which I definitely need to rectify.

My decision to use a computer less means that I’m going to print out manuscripts more. In the last couple of years, I’ve written whole manuscripts through to final edits without once printing the story out. Now, I can do a lot of the final editing straight onto paper, which it turns out, is a nicer process (who knew?).

And actually, just getting on with it and doing it quickly means that I’ll get into better habits and some of those Type 2 activities may well move back over to Type 1 ones.

A writer friend of mine said recently “Writing doesn’t always look like writing”. It’s very true, but without having the option of Facebook during the day, more of the things I'm doing now that aren't physically writing are genuinely part of the "writing doesn't always look like writing" writing.

Use positive distractions. I know that I need to distract myself sometimes and Facebook has often been my distraction of choice, in the way that chocolate is my snack of choice if it’s in the house. But I know that I’m much better off having healthier snacks easily accessible and not having an unhealthy alternative available. My post-retreat healthy option distraction is a (non-story) book. I’m keeping it near me when I write, and if I really need a quick procrastinating dip into something, that’ll be it.

[5] More writing outside (Whoops, that last point was so long I forgot I was doing a list!)- I really enjoyed the opportunities I had to work outside –researching, brainstorming, structuring and actual physical writing by hand.

It wasn’t often warm enough to be stationery outside for long but when it was, I was out, even when I had to be in several jumpers, a coat, hat and scarf and woolly fingerless gloves…

I need to do that more. And now with less emphasis on my computer, I can –and will- do that.

[6] Make the most of the stillness. I loved it in the morning when I wrote before having spoken to anyone or listened to anything on the radio etc. I used to do this at home by getting up at 6am and getting an hour in before anyone woke up. And I’m determined to go back to that again, having reaped the benefits of the stillness of it on retreat.

[7] Recognise that this all happens in real life. I was able to go on retreat for a week but in real life, I have three amazing and highly distracting children who need to be loved, fed, played with and taken to, and collected from, school every day. I need to make all these changes within my real life and be more efficient whilst I’m working so that once they’re home, I’m theirs alone until they go to bed. More efficient includes using a separate (A4 hardback unlined) notebook for every project I do from now on, so I don’t lose any of my thoughts because they’re in one of twenty or thirty notebooks that are on the go at the same time.

I’m starting a reflection journal so I can work out what’s working well and what could work better. This is so useful for best practice, particularly with school visits, but I think it’ll be good for writing, too. And I think that keeping my computer out of view means that I can be much more present in work and life (and I hope it’ll help my children to grow up not thinking that on-line life is more interesting than real life).

And finally, I’ve found a way to recreate the retreat experience as closely as possible one day a week, when the children are not here. I will have a computer-free day where I don’t actually speak to anyone at all, in person, or on the phone or online from when I wake up until I pick the children up from school. No radio, no internet, no opening up a computer, no voices at all apart from my characters’.

I made a plan whilst I was away and it still looks completely doable now I’m back. I’m going to stick to it. I’m going to take more risks and make more mistakes, and though I’ll make myself do some Type 2 fun every day, I reckon there’s going to be an increasing amount of Type 1 fun on its way.

A story, brainstormed, structured and written as a really rough first draft, mostly outside, and not going near a computer until I'd handwritten THE END, and all in one day...

Thanks to fellow writers, Ali and Annie, for a fab week.

What about you and your writing? Which parts of the book creating process are currently Type 2 fun for you?

www.julietclarebell.com

Published on April 10, 2015 10:06

April 4, 2015

MY PICTURE BOOK JOURNEY by Saviour Pirotta

I have to confess that I had never seen a picture book till I moved to England in the early 1980s. I was given, and treasured, quite a few heavily illustrated classics when I was a boy but they weren’t really picture books. They were what David Lloyd at Walker Books would call illustrated stories. Take away the pictures and the story would still work.

Then one day I walked into Swiss Cottage Library and there, stacked up in enormous wooden crates on legs, were hundreds of them. I felt like Tom the chimney sweep’s boy when he beheld his first water baby. It was love at first sight. Here was a world I was desperate to be part of.

I bought a notebook and a Bic and started writing my own picture books there and then. It was the start of a learning curve that is still curving twenty five years later.

I was really lucky with my first text, called Let The Shadows Fly. I sent it to Hamish Hamilton and they bought it. It didn’t sell very well but it got me some fantastic reviews and a real horrible one in The Guardian where the critic said it would give her three year old nightmares. The book was aimed at 4 – 7 year olds so she hadn’t done her homework [and nearly thirty years later I’m still hoping she’ll write a children’s book so I can get mow own back on amazon]. That first book taught me two valuable lessons I have never forgotten. No matter how many good reviews you get, it’s always the bad ones you’ll remember. We’re sensitive creatures.

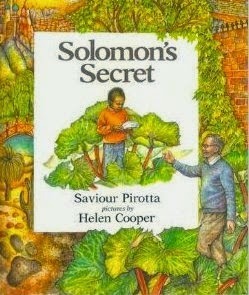

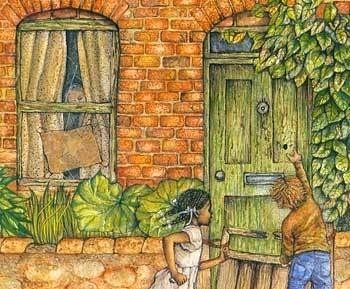

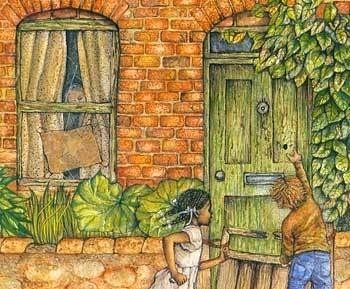

But, seriously, the second lesson was a tougher one. Don’t write picture books if you want to be lauded as a real author. People will tell you, ‘we love the pictures,’ but they’ll never comment on your text. Not even if they’re a head teacher introducing you at assembly as their book-week author. You might have the initial idea for the book, you might write a text that flows with the force of the Nile in inundation, but your book will stand or fall on the pictures. Indifferent illustration will ruin a good story but great illustrations never seem to save a limp text. My first ‘breakthrough’ picture book was Solomon’s Secret in 1988.

It was illustrated by Helen Cooper before her Kate Greenaway awards and published by the wonderful Janetta Otter-Barry at Methuen before she left to set up the children’s list at Frances Lincoln. This book taught my third and perhaps most valuable lesson. Only work with an editor you trust. She will make or break your book. If she has vision, if she can see the end result, go with her vision not yours. She’ll come through for you.

Solomon’s Secret sold very well, got numerous foreign co-editions and was one of the very first books with a black child on the cover to be published in South Africa after the end of apartheid. And right there, was lesson number four: a lot of publishers will only go ahead with a project if they can get foreign co-editions. Full colour books are prohibitively expensive to produce and many publishers can only afford to take them on if they can share the costs with their foreign counterparts. That rules out stories that would only work in one country, and illustrators who style does not ‘travel’.

In the end, I got lured away from picture books into the gift book market where I continue to do really well. I still couldn’t get head teachers to comment on my writing at the start of assemblies but at least there were so many words in the books they couldn’t be ignored.

I never gave up on picture books entirely though and when four years ago Templar invited me to write a text for the incredible Catherine Hyde, I jumped at the chance. Last year I attended the Scattered Authors society writer’s retreat at Folly Farm in Bristol and found out that some of my writing pals [Abie Longstaff, Jane Clarke and Rebecca Lisle] were holding a picture book session. I was struggling with a text I somehow couldn’t nail down and asked if I could join them.

The session proved incredibly fruitful. There’s something magical and empowering about sharing half-formed ideas and stories with your peers. I soon found out my story had a major flaw that I couldn’t mend. But during the session [actually during a trip to the loo half way through the workshop] I had another idea, which sent my picture book writing in a totally different and unexpected direction. The story is now with my agent who loves it. Watch this space! I might have some good news soon.

Saviour Pirotta is the best-selling author of many books for children, including The Orchard Book of First Greek Myths, The Orchard Book of Grimm's Fairy Tales and Firebird, winner of the Aesop Accolade 2010.

Find out more about Saviour at www.spirotta.com or follow him on twitter @spirotta.

Then one day I walked into Swiss Cottage Library and there, stacked up in enormous wooden crates on legs, were hundreds of them. I felt like Tom the chimney sweep’s boy when he beheld his first water baby. It was love at first sight. Here was a world I was desperate to be part of.

I bought a notebook and a Bic and started writing my own picture books there and then. It was the start of a learning curve that is still curving twenty five years later.

I was really lucky with my first text, called Let The Shadows Fly. I sent it to Hamish Hamilton and they bought it. It didn’t sell very well but it got me some fantastic reviews and a real horrible one in The Guardian where the critic said it would give her three year old nightmares. The book was aimed at 4 – 7 year olds so she hadn’t done her homework [and nearly thirty years later I’m still hoping she’ll write a children’s book so I can get mow own back on amazon]. That first book taught me two valuable lessons I have never forgotten. No matter how many good reviews you get, it’s always the bad ones you’ll remember. We’re sensitive creatures.

But, seriously, the second lesson was a tougher one. Don’t write picture books if you want to be lauded as a real author. People will tell you, ‘we love the pictures,’ but they’ll never comment on your text. Not even if they’re a head teacher introducing you at assembly as their book-week author. You might have the initial idea for the book, you might write a text that flows with the force of the Nile in inundation, but your book will stand or fall on the pictures. Indifferent illustration will ruin a good story but great illustrations never seem to save a limp text. My first ‘breakthrough’ picture book was Solomon’s Secret in 1988.

It was illustrated by Helen Cooper before her Kate Greenaway awards and published by the wonderful Janetta Otter-Barry at Methuen before she left to set up the children’s list at Frances Lincoln. This book taught my third and perhaps most valuable lesson. Only work with an editor you trust. She will make or break your book. If she has vision, if she can see the end result, go with her vision not yours. She’ll come through for you.

Solomon’s Secret sold very well, got numerous foreign co-editions and was one of the very first books with a black child on the cover to be published in South Africa after the end of apartheid. And right there, was lesson number four: a lot of publishers will only go ahead with a project if they can get foreign co-editions. Full colour books are prohibitively expensive to produce and many publishers can only afford to take them on if they can share the costs with their foreign counterparts. That rules out stories that would only work in one country, and illustrators who style does not ‘travel’.

In the end, I got lured away from picture books into the gift book market where I continue to do really well. I still couldn’t get head teachers to comment on my writing at the start of assemblies but at least there were so many words in the books they couldn’t be ignored.