Simon J. Cook's Blog, page 17

June 10, 2014

Governing Philosophy

Back in the 1970s the New Left used to ask why England had never produced a Durkheim, a Marx, or a Weber. The point of the question was to draw attention to the presumed poverty of theory in the English intellectual tradition (thereby bolstering the importation of those Continental theorists who now form the postmodern canon of undergraduate life). But the presumption was wrong and the question wrong-headed.

It is true that late-nineteenth-century England did not produce any one great social thinker; but it did produce a governing philosophy; albeit a philosophy all but forgotten today.

I stumbled upon this realisation only in the last few days, and very much by accident. A while back I agreed to attend a conference on the obscure Victorian philosopher John Grote (1813-1866). I was asked because I’m one of the few people who have studied Grote’s writings, having identified his thought as key to Alfred Marshall’s reformation of political economy. Thinking again about Grote, I recalled recently encountering the mark of his thought in the writings of the classical archaeologist William Ridgeway (1853-1926). Over the last few days I’ve been juxtaposing Grote’s philosophy, Marshall’s political economy, and Ridgeway’s theory of the origin of ancient Greek tragedy. By now I am convinced that when all three are (as it were) placed together and held up to the light what appears is something like England’s governing philosophy.

I suspect that this is a theme I’ll have to return to several times; but let me attempt here to sketch the very basic ideas at hand.

In mid-Victorian Cambridge, Grote’s challenge was to allow a scientific study of humanity without undermining traditional religious belief. His solution was a dualistic philosophy of the human mind that distinguished between (on the one hand) ordinary mental life, which was to be studied by science, and (on the other hand) self-conscious reflection, the study of philosophy and (he argued) the path to knowledge of God.

Marshall and Ridgeway adopt Grote’s dualism in a very particular way. In a nutshell, they develop historical accounts (i.e. of the behaviour of some human system in time) that turn upon an internally inexplicable evolutionary leap. On close inspection, that leap is revealed to be the product of intervention by a ‘higher mind’.

Let me briefly sketch three such evolutionary leaps; only then will I appraise the nature of the external intervention that supposedly caused them.

Ridgeway on the birth of tragedy: the primitive inhabitants of the Aegean worshiped the ghosts of dead chiefs and heroes, performing hymns and dances at their tombs. Naturally, such primitive beliefs about ghosts would evolve into beliefs about gods (who are no longer tied to one location). Tragedy is the product of a non-natural development of these death rituals, with the dancers and songs transforming into a drama and chorus.

Marshall on the birth of imagination: in the late 1860s Marshall developed a two-level mechanical model of the mind. The first level is composed of automatic responses or mental habits (e.g. see red light, foot presses on brake). There is little more to the minds of all animals and primitive humans than this first level.

At some point in human history a second level of the mechanical mind has emerged, which allows the picturing of different possible outcomes of an action: imagination, deliberation, and foresight are born.

Marshall on classical political economy and neoclassical economic science: by the 1870s Marshall is seeing British society as composed of an elite, who possess imaginative minds, and the working masses, whose productive activity demands only lower level automatic responses. Classical political economy, with its emphasis upon deterministic laws of production, is appropriate for such a society.

But Marshall now proposes a new economic theory founded upon the novel assumption that the masses have been taught to think. In his neoclassical economics the primary economic activity is decision-making in the market, and all economic agents are assumed to deliberate by imagining different possible futures.

In each of these three cases the lower level system is transformed by way of external intervention.

For Ridgeway the key to the birth of Greek civilization was, first of all, an invasion of Greece by a spiritually superior race from the North, and, subsequently, political legislation in Athens that injected this Northern culture into the still primitive Athenian social system.

For Marshall the initial emergence of the second level of the human mind was the product precisely of the intervention of Grote’s self-consciousness or ‘higher mind’. But the transformation of society that would validate the transformation of economic theory was to be achieved by way of a massive state provision of universal higher education.

Overview: what is emerging into view is a scientific approach to the human world that embodies a hierarchy of values and a faith in elite intervention for the benefit of ‘primitives’. The key scientific assumption (which I do not think is found in Grote) is that progress is not necessarily natural, that primitive humans are unlikely to progress without external intervention. Such intervention may take the form of conquest and colonial rule abroad or the establishment of a welfare state at home.

Looking further, one can begin to understand the peculiar reverence that, for the last century, has attached itself to the Cambridge supervision system, whereby one don engages directly with one or two undergraduates: here is the internal reproduction of the ‘higher mind’, the cultivation of a new elite. Or on a different note, the General Theory (1936) of John Maynard Keynes, which introduced the idea that the capitalist system might get stuck in a permanent depression the only way out of which being state intervention, comes into view as but a late instance of this Cambridge governing philosophy.

May 29, 2014

Aliens or immigrants? Watching by the threshold

For an exercise in irony, try asking some British Jews about Muslim immigration. Perhaps because I live in Israel (and my sympathy is thereby assumed) I’ve heard a lot on this score. But almost every stereotype leveled is a modification of accusations hurled against Jewish immigrants to Britain a century ago.

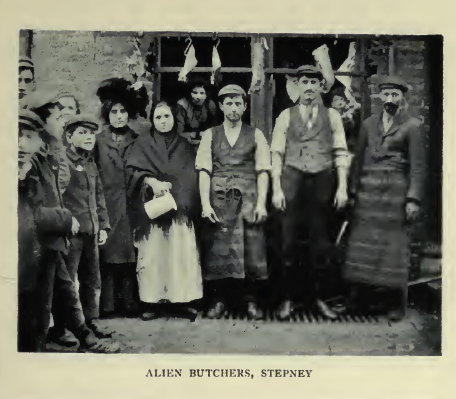

A series of pogroms in Russia in the 1880s set in motion several waves of mass Jewish emigration. Domestic unquiet in the face of this ‘alien invasion’ and the new ‘ghettos’ of East London sparked intense public debate, culminating in the Aliens Act of 1905, the first modern legislation restricting immigration.

From ‘The Alien Immigrant’ by Major Evans-Gordon, M.P. (London, 1903)

The echo today of the prejudices of the past is astonishing: suspicion of Kosher/Halal butchers, fear of halacha/sharia law, belief that Jews/Muslims possess a unique resistance to assimilation into British culture. At root is a common conception of an alien community inherently antithetical to British society.

But the parallels go deeper, and bringing them to light may illuminate a more general feature of the modern immigration debate.

British Jews who complain about Muslims in Britain today do not deny their own descent from immigrants; they simply imply that their forefathers were good immigrants. Oddly enough, the same kind of attitudes were fostered by the British who legislated against Jewish immigration a century ago.

As newspaper editorials and members of parliament debated Jewish immigration, Britain’s scholars were reevaluating the ethnological history of the British Isles. To see the shift in thinking that occurred at just this time look at the these two depictions of ancient British history:

From ‘Our Island Story. A History of England for Boys and Girls’, by H.E. Marshall, illustration by A.S. Forrester (London, 1905)

The picture above reflects the traditional nineteenth-century conception of ancient British history: ’native Britons’ watch the arrival of the Roman fleet of Julius Caesar (a sort of ancient ‘close encounters’ moment). Contrast these primitive Britons, with their black hair, animal skin clothing and lack of shoes, with the blond giants below.

From ‘Beric the Briton. A Story of the Roman Invasion’, by G.A. Henty, illustrator unknown (London, 1893)

Although this second picture was published earlier, it embodies the newer historical thinking. The ancient Britons are still ‘Celts’, but the Celts are now understood to be Aryan warriors, racially akin to the Anglo-Saxon invaders who came after them, the forefathers of the English.

At the heart of these (entirely typical) representations is a sharp dichotomy between aborigine and newcomer. For much of the nineteenth century it was assumed that the Celts were the original inhabitants of the British Isles. As such, the Celts were the passive victims of British history: invaded and pushed aside by new and more vigorous races. By the end of the century, however, it was believed that the British Isles had once been inhabited by pre-Celtic Neolithic farmers. The Celts thus became invading immigrants in their own right, on a par with the Anglo-Saxons.

Who were the newly discovered natives? With precious little archaeological or philological evidence to work with, scholarly and literary imaginations turned to racial anthropology, evolutionary theory, and fairy tales.

As the Celts became larger and blonder, so the posited British aboriginals became smaller and darker. Definitely non-Aryan, the aboriginals were connected to modern Basques and an ancient ‘Mediterranean race’.

Give these aboriginals a coat of bodily hair and an evolutionary missing-link was at once established: here is the origin of the queer-thinking but peaceful Neanderthals of William Golding’s 1955 novel The Inheritors.

But the most scholarly depictions of the original settlers of Britain were derived from the study of folklore. In 1900, John Rhys, the Oxford Professor of Celtic, proclaimed that Welsh fairy stories contained dim memories of Britain’s aborigines, who he inferred to have been a ”small swarthy population of mound-dwellers, of an unwarlike disposition, much given to magic and wizardry.”

John Buchan’s short story ‘No-Man’s-Land’ combines the second and third of these themes. An Oxford scholar of Northern Antiquities (like Rhys perhaps, or one of his students), on holiday in the remote Highlands of Scotland, encounters – and is then taken captive by – the Hidden People:

Then suddenly in the hollow trough of mist before me… there appeared a figure. It was little and squat and dark; naked, apparently, but so rough with hair that it wore the appearance of a skin-covering… in its face and eyes there seemed to lurk an elder world of mystery and barbarism, a troll-like life which was too horrible for words.

John Buchan, ‘The Watcher by the Threshold’, 1902

‘No-Man’s-Land’ appeared in Buchan’s collection of stories The Watcher by the Threshold, which was published in 1902, just as the debate over Jewish immigration was gathering momentum.

Clearly, what we witness here is the simultaneous construction in Britain of several opposing identities. First and foremost, Celt and Saxon are being melded together into a more unified British identity: inhabitants of the land descended from various invading warriors, all masters of their own history.

As such, the British contrast themselves with the victims of history, be they the weak and passive aborigines who hide in the face of successive invasions, or those who are blown across the earth by the bitter winds of war, poverty and oppression – those we now call refugees.

A more comprehensive picture would bring into view that flourishing Edwardian invasion literature that imagined the German army attempting to invade Britain (a classic of this genre being Erskine Childers’ 1903 novel, The Riddle of the Sands). Here the Germans provide another kind of opposite to the British – rivals for mastery, enemies but equals.

Further analysis of the similar representations of aborigines and Jews would also be illuminating. Buchan’s Oxford don is held captive in a mean, squalid and crowded cave, a sort of prehistoric ghetto. More generally, both groups (as with the Muslim immigrants of today) are imagined as communities that willfully place themselves outside the mainstream society, composed of individuals who care only for their own. Victims of history they may be, weak perhaps in mind and spirit, but they are cunning and devoid of scruple when it comes to their interactions with the honest British public.

But all I want to highlight here is the fairly straightforward fact that the newly constructed British identity was, ultimately, an immigrant identity. The British of 1905 who pioneered state immigration controls saw themselves as descended from a mixed bunch of immigrants.

What frightened people, then as now, was not the immigrant but the alien. As Buchan’s story shows, the alien need not be the immigrant. And as the new British history demonstrated, the immigrant need not be an alien.

This British response to the Jews of 1905 is echoed a century later by the great-grandchildren of those same Jews, or at least those who have now assimilated: “we too were once immigrants to this land; we do not dislike you because you are immigrants, but because you declare yourselves different to us and bear the mark of the alien.”

Of course, not all Jews did assimilate into British culture (and assimilation itself has its degrees). Some retained their traditional religious identities, replete with that Eastern European form of dress that today in Israel and North London mark out the orthodox ‘yeshiva bochur’. Others, concluding that the ‘goyim’ or nations of the world would never allow the Jew to live in peace among them, left Britain for Israel. To such Zionists, the mark of the alien was ineradicable, assimilation an impossibility. Today in Israel the orthodox and the secular are engaged in a bitter struggle to claim the Jewish identity for their own. The mark of the alien may be claimed as a badge or pride as well as hurled in complaint; and those who claim it may contest bitterly its essential nature.

Notes

My understanding of the Edwardian debate over Jewish immigration is much indebted to the excellent research of Yoni Eshpar.

My discussion of changing British identities in light of new theories of prehistory draws upon my forthcoming article in the Journal of the History of Ideas: ‘The Making of the English’.

I would like to assure my British-Jewish friends and relatives, as well as any Anglo readers in Israel, that the first paragraphs above do not refer to any opinions that they have expressed, but rather reflect the prejudices of others, perhaps like them, but less wise.

May 26, 2014

Beowulf and UKIP

Two events of the last couple of days have arrested my attention: the much hyped launch of J.R.R. Tolkien’s translation of Beowulf and the astonishing electoral success of the anti-EU British political party, UKIP.

What do these two events have in common? From the more or less (mainly less) interesting media pundits I’ve been reading, nothing at all. But a better awareness regarding the first might have helped stem the tide of the second.

Let’s agree that some (certainly not all) of the UKIP electoral success arises from a smoldering English nationalism. Well, Tolkien was a great English nationalist; one of the greatest. His fantasy writing was bound up with his desire to rediscover (read: create) a lost English mythology. But a moment’s reflection upon the content of Tolkien’s English nationalism reveals it as inextricably bound up with Continental myths, legends, and history. Middle-earth is not ancient England, it is ancient Europe; the Shire is not even separated from the Continent by a salt-water channel.

Let’s agree that some (certainly not all) of the UKIP electoral success arises from a smoldering English nationalism. Well, Tolkien was a great English nationalist; one of the greatest. His fantasy writing was bound up with his desire to rediscover (read: create) a lost English mythology. But a moment’s reflection upon the content of Tolkien’s English nationalism reveals it as inextricably bound up with Continental myths, legends, and history. Middle-earth is not ancient England, it is ancient Europe; the Shire is not even separated from the Continent by a salt-water channel.

Beowulf illustrates this perfectly. This English epic, the most splendid poem composed in Old English, concerns a monster named Grendel who terrorizes the King of Denmark. The hero Beowulf is a Geat, who sails to the aid of the Danes from his home in what is now southern Sweden.

Tolkien’s own stories weave together distinct parts of an English mythology that, he wanted to believe, were once told by the ancient ancestors of the English nation who inhabited the shores around the North Sea and the Baltic. Tolkien’s English mythology is a Continental mythology.

Today, very few study these Old English stories from Tolkien’s perspective. In most scholarly circles English nationalism is a dead letter; and few self-respecting scholars of English literature are going to give it a sympathetic treatment.

But English nationalism is alive and kicking in the wider world of good old England; as the recent electoral results make only too clear.

If today’s young Tolkien experts were a little less concerned with what is politically correct and a little more concerned with the wider world beyond their (very) narrow specialisms, discussion of Tolkien’s Beowulf might have spoken to the public at large. In place of wide-eyed media hype we might have heard how pride in an English identity can embrace – rather than fear and loathe – the idea of belonging to Continental Europe.