Martin Lake's Blog, page 20

September 11, 2012

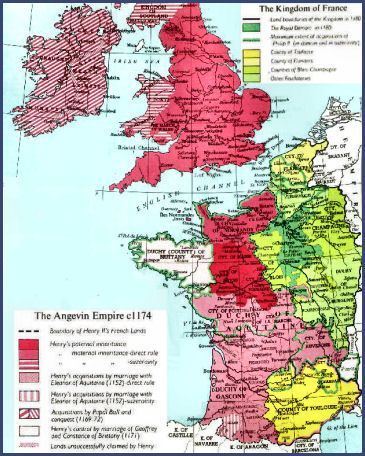

The Heart of the Norman and Angevin Realms

When I was young I idolised King Richard I of England, the Lion Heart. I loved the television series starring Dermot Walsh and was enthralled as my father carefully put together an Airfix model of my hero.

Later, when I found out that Richard spent only six months of his ten year reign in England I felt disappointed. Later still, when I found out how he had used the kingdom and people as a vast treasury to fund his dynastic wars and crusade I felt almost a sense of betrayal.

Yet now in that I am writing the third book in my The Lost King I begin to understand things a little better.

During the course of the third book Edgar has been forced to leave his sanctuary in Scotland. He spends several years in northern France, taking his war into William the Conqueror’s Dukedom of Normandy.

As I have researched it I began to see why William, like the later Richard, spent so little time in the kingdom he had so recently conquered.

It was because for both men the centre of their power and certainly the focus of their concerns lay not in England but in France. Normandy was only one of a number of powerful territories all owing suzerainty to France. There was constant warfare and conflict between the lords of these lands and with the king himself.

The conquest of England gave William the right to call himself King and therefore, believe he was in some sense the equal of Philip I of France. Yet the heart of his rule was and remained Normandy. Once he had quashed the resistance to his rule in his new kingdom he turned his attention to Europe once again and only returned to England for short and infrequent visits.

I realise now that Edgar can and will operate on a far grander canvas than hitherto.

September 9, 2012

The Artful Dodger meets the Fowler household. #SampleSunday #Kindle

Dr Fowler commanded Jack to sit on the stool and remain silent. All four turned expectantly towards the door as it opened and Surgeon Wills walked into the room.

He beamed upon Fowler and Beatrice and bowed cordially to Lambert who had quietly stood up and taken a place beside the fire-place.

Wills had been in the house a number of times and he found it very pleasant after a life spent mostly upon board ship. He cast his gaze upon the comfortable furniture, the homely knick-knacks, the pleasant paintings and the rows of books.

Then his gaze alighted upon Jack. His eyes stopped for the briefest moment and moved on towards the sideboard. His eyes returned once more to Jack. They moved on once again, to Beatrice. Once more, however, they were inexorably dragged back.

He peered closely, sought out his pince-nez and peered even more closely.

‘My goodness,’ he cried. ‘It’s young Dawkins.’

Jack sprang to his feet and rushed across to the surgeon, grabbing his hand and shaking it enthusiastically.

‘Hang on, Jackie,’ Wills said. ‘I’m not a water-pump.’

‘Sorry, Mr Wills,’ said Jack. ‘It’s just that I’m real pleased to see you.’ He turned towards Lambert, bristling with vindication.

‘It seems we owe the boy an apology,’ Fowler said.

‘Possibly,’ said Lambert. He turned to Wills. ‘It’s clear that you know the boy,’ he said. ‘But he claims that he assisted you in the infirmary. Is there any chance that this is true?’

‘Every chance,’ answered Wills. ‘He was invaluable to me. Better than some of my paid assistants. The boy is quick-witted and nimble-fingered. He was adept at putting on dressings. Once, as I recall, he even stitched a convict’s wound.’

‘Told yer,’ Jack said triumphantly.

‘I’m sure he’s nimble-fingered,’ said Fowler. ‘It’s probably the reason he’s in New South Wales.’

‘That’s true for certain,’ Wills said. He gave Jack a look which was a mixture of the stern and the fond.

‘This, my dear friends,’ explained Wills, ‘ is the notorious Artful Dodger. He was the chief lieutenant of one of the worst criminals in London. No doubt, had he not been caught, he would have become an equally infamous criminal chief in due time.’

‘Artful Dodger?’ said Beatrice. ‘What a peculiar title.’

‘Artful because he was the most adroit picker of pockets in the Capital,’ said Wills. ‘And Dodger because once he’d made his steal he would duck, dive and dodge faster than any policeman could follow. It’s all in his record, which I had occasion to read on board the transportation ship.’

‘Lambert here wants me to take me into my home,’ said Fowler. ‘What do you think of that?’

Wills considered. ‘It’s a risk. I’ll not deny it. But Jack Dawkins is as bright as he’s cunning. He can read a little and write the odd word. If you can turn his blackened soul to goodness then he may prove a good servant.’

‘Oh let’s try to turn his blackened soul,’ cried Beatrice. ‘Please, Father, let’s try.’

Fowler smiled fondly at his daughter. He always found it hard to refuse her.

He considered it carefully and at great length. The others fell silent and waited. Even the sofa appeared to hold its breath.

‘We shall try,’ he said at last. ‘We shall give him a trial.’

‘A trial?’ Jack said. ‘I don’t want no more trials.’

Fowler laughed. ‘By trial I mean we will keep you here for a while, maybe two months. If you prove yourself amenable and hard-working, and eschew wrong-doing completely, then you will be given an extension of six months. We will review your behaviour every six months thereafter.’

‘That’s harsher terms than Parliament operates on,’ said Lambert with a whistle. ‘But I don’t think you’ll get fairer than that, Jack Dawkins.’

‘But will Governor Gipps agree it?’ Fowler asked, suddenly doubtful.

Lambert nodded. ‘I think so. He will want to please Chief Killara.’

‘Then it’s settled,’ cried Beatrice with joy.

Fowler turned to Jack with a stern look. ‘First my lad, you shall have a bath.’

Jack backed towards the wall, his hands held up as if warding off an enemy.

‘No I won’t,’ he said. ‘A bath robs your strength and addles your brains. Everyone knows that.’

For answer, Fowler rang the bell. The maid entered immediately. She blushed, realising that her speed would indicate she had been listening at the door.

‘Lisa,’ Fowler said, ‘ask Mrs Bullmore to join us.’

Lisa curtseyed and disappeared.

Two minutes later she reappeared. Her face looked rather strained. ‘She’s coming,’ she said. ‘She was in the middle of a pie.’

She felt a presence behind her and stepped to one side.

Mrs Bullmore stepped into the room and, with a magisterial look, surveyed them all.

‘I was in the middle of a pie, Dr Fowler,’ she said.

She was a small woman, not quite five feet high but appearing almost as many broad. She was dressed in black for she was a widow. A white smock covered her upper body. It had, no doubt, been clean this morning, but now it looked like the apparel of a murderer.

Blood stains were spattered across the front of the smock in a diagonal line, the result of a fearsome contest with a hen reluctant to give up its life. Mrs Bullmore was a firm believer in serving only the freshest of food and, wherever possible, preferred to dispatch her own rather than leaving this task to the butcher.

One of the hen’s feathers was lodged in a pocket, either a belated attempt at surrender on the part of the fowl or a trophy of war on the part of Mrs Bullmore.

Below the blood could be seen a thick smear of butter, flour and lard. Arranged upon this foundation were gravy stains, picked out in the shape of Mrs Bullmore’s small but heavy hands.

She wore a linen cap upon her head but this had proved inadequate for its job and her hair was festooned with traces of flour, sugar and egg, the residue of a recalcitrant lemon meringue pie.

She stood with a large knife, which appeared covered in brown gore, and fixed Fowler with her stare.

‘I’m sorry to have interrupted your work,’ Fowler said.

‘It was your pie I was in the middle of,’ she said.

‘Of course,’ Fowler said. ‘But I wanted to show you Jack Dawkins. He is to join the household. And, directly you have finished your lunch duties, I want you to give him a bath.’

Mrs Bullmore stared at Jack. She took a deep, satisfied intake of breath. ‘It will be my pleasure, Dr Fowler,’ she said.

Jack cringed, feeling almost as threatened as he used to be by Bill Sikes.

*****************

For a short time only Artful is available on Kindle for at a reduced price of $1.22, 77p or €0.89. It can be borrowed free in the USA by Amazon Prime customers.

September 7, 2012

Friends

Our very good friends Chris and Gina have arrived here for a week’s visit.

The last time we saw them was on the day we left England. They came round to take us to the airport hotel and found us floundering and panic-stricken in the middle of an impossible number of jobs which seemed to have appeared out of nowhere.

‘Don’t worry,’ they said. ‘We’ll take whatever you can’t pack to the charity shop or the dump.’

They disappeared while we drew breath and managed to get the last of our life in something nearly resembling order. They returned an hour later, took us to the hotel, had a drink with us and left as quietly and as encouragingly as they had appeared a few hours earlier.

And now, after almost a year, we are back together again. It’s lovely.

I am reminded, not that I needed to be, of the value and joy of true friendship. It’s like a literature of life.

September 1, 2012

“Back to School, Children.” An extract from ‘The Big School.’ #Kindle #Author

As a kid I always used to hate it when the summer holidays started and shops immediately began to advertise items under the banner ‘Back to School.’ Reminding us of the next school year when we’d just started our six week holiday seemed a particularly malevolent form of sadism.

So, now I’m a grown-up (of sorts) I thought I’d add to the tradition by posting a sample of my children’s stories. I wrote these many years ago when I was a school teacher and used to read them to my class to see their reaction, claiming they were written by an acquaintence. They were the best audience and editorial team I could hope for. If they liked something, or hated it, I could see it in their faces. Thanks very much, kids.

Here’s the start of the series, from the collection ‘The Big School.’

********

LITTER

I turned over in my bed for what must have been the millionth time that night. The sheets were that ruffled it was like a ploughed field and my pillow had turned all wrong in the darkness. The next day I was going to Braithwaite Comprehensive, the big school, and I’d not slept a wink all night.

Willie Belfield who lived up our street had been at Braithwaites a year now and since the first day of the six weeks holiday he’d been telling me things about it.

There was this teacher, Mr McTavish. He took PE and was the cruellest man in the world. He used to make kids do impossible things in the gym and when they couldn’t do them he’d go mad and hit them over the head with this chunk of wood. They reckon all the other teachers were scared of him.

Then there was a maths teacher, Mr Batty. He had right bad breath and he used to talk to you ever close so that you had to smell it and feel sick. And when he got mad he used to throw board-rubbers and compasses at people and sometimes even chairs.

But even worse than the teachers were kids. They were always getting you, especially if you was a First Year. When Willie Belfield first went he came home crying because big kids had put slime in his shoes and set fire to his tie. He said us First Years could reckon on being beaten up four times a week.

The first day was supposed to be the worst. It was on the first day that everybody had their heads put down the toilet in the chain pulled.

The only kid in the whole school who’d not had his head put down the toilet was our Eric. He was going to be a fourth year now and when he first started the school was even worse. But he still managed not to have his head put down the toilet. According to Juddy, our Eric’s best mate, the first day they started school all the big lads rounded up the First Years for the toilet treatment.

Of course, they were all screaming and kicking and threatening to bring their big brothers round; all except our Eric. According to Juddy our Eric was near the back of the First Years and was jumping up and down making out that he was dead excited at the thought of having his head put down the pan. He called out to the big lads to hurry up because he couldn’t wait to have his turn.

So they all looked at him funny and decide not to do it to him. Just to spite him. He put on a right show about it, sulking and moaning, saying it weren’t fair. But Juddy says that when our Eric walked past the drenched kids with his hair bone dry he gave a wink and a smile.

I turned over again and sighed. I weren’t like our Eric. As soon as I walked into the playground I’d be yanked off to have my head put down the toilet. Or perhaps even Mick Patterson would get me.

Willie Belfield had told me about Mick Patterson. He was this right big kid and everyone was scared of him. What he did was pull down your trousers and underpants and write swear words on your bum with indelible ink. And of course Mr McTavish would see it in the showers and you’d be half murdered by him. I kept wondering what it would be like to have someone write swear words on your bum or have your head put down the toilet and the chain pulled. I thought that perhaps if you have one thing done they wouldn’t do the other and I kept trying to work out which was the least horrible.

When I got up next morning my eyes had dark circles under them like I’d been given two black eyes already.

Our Eric shook his head when he saw me. ‘Have you been awake all night?’ he asked.

I nodded my head.

‘You shouldn’t be so daft,’ he said. ‘Don’t believe half what people tell you.’ He put milk on my cornflakes for me. ‘And even if the worst does come to the worst,’ he continued, ‘having your head put down the toilet isn’t that bad.’

‘It’s all right for you to blinking say that,’ I replied, ‘you never had anything done to you.’ But he did make me kind of feel better. He had to finish my cornflakes mind.

Juddy called for Eric on the way to school but they didn’t seem to mind me walking with them.

I met my best mate Pricey at the school gates. He looked right funny in his uniform. I suppose I did as well. Mind you I didn’t look as though I put my tie on with my feet like Pricey did.

It were a right shock when we got into the playground. We were used to being the biggest at the Junior School but now we were the smallest. Everybody looked like giants; some of the biggest lads even had moustaches. And everyone wore uniforms. It looked ever so strange as though it wasn’t a real place.

You could easily tell the First Year though. They were all huddled together trying to look like they weren’t there. Some were stood stock still against the walls as though they were hoping their black uniforms would blend in with the grey of the concrete. All round the First Years prowled gangs of older kids. It was obvious they were looking for someone to get.

Suddenly somebody tapped me on the shoulder. I jumped about six foot. I turned round to see this really strange looking kid. He had great big floppy ears and eyes which were nearly popping out.

‘What you want?’ I asked. My voice was all high-pitched with fright.

‘I ask all the questions,’ he said. Me and Pricey looked at each other; his voice sounded even higher than mine.

‘Are you First Years?’ he asked.

We nodded.

He looked at Pricey’s peculiar tie. ‘Did you tie that?’ he asked.

Pricey nodded.

‘Are you mad?’ he asked with his head to one side.

Pricey’s not, I thought, but I bet you are.

Pricey shook his head.

The strange kid turned to look at my tie. ‘Did you tie that?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ I lied. Our Eric had done it for me really.

‘It’s a nice tie,’ said the weirdo and suddenly whipped out this pair of scissors and cut it off. Before I could stop him he’d stuffed my tie in his mouth and started eating it. Me and Pricey looked at each other in amazement; this place was like a loony bin.

The weirdo had only just finished eating my tie when a whistle blew. Everybody stopped moving. It was like the kids had been turned to stone or had seen a ghost. Then two whistles blew and everyone started running like they were mad.

The weird kid pelted past us crying, ‘McTavish!’

We didn’t know what to do, none of us First Years did. We were all terrified. We ran around in circles, not knowing where to go, banging into each other, falling over and nearly crying. We must have looked just like ants when you lift a stone from off of their nest. Out of the corner of my eye I could see Mr McTavish glaring at us. He had a huge piece of wood in his hand.

‘Stop running,’ he bellowed.

Me and Pricey collided with each other and fell over. Every First Year was shaking with fear.

‘Now then,’ said Mr McTavish, sneering at us like some baddie in a cowboy film, ‘stay silent and listen to me. My name is Mr McTavish.’

He held the piece of wood above his head. ‘And this is what I call my “Persuader.” It’s rather heavy, rather like a caveman’s club. And it hurts.’

He suddenly whipped the club against the wall, making a crack like a rifle shot echo around the playground. I shuddered.

‘And if,’ continued Mr McTavish, ‘any First Year is not lined up silently within five seconds of my blowing his whistle, they will feel my “Persuader” around their backsides.’

He pointed to another playground where all the other boys were lined up. There were two flights of steps up to it. The whistle blew and everyone ran for their lives. I’d never have thought it possible but over a hundred First Years leapt up those steps and were lined up in silence in a lot less than five seconds.

*********************

‘The Big School’ is available from most retailers priced 77p, $1.21 or €0.89. Give it a try.

The second in the series, ‘The Guy Fawkes Contest’ will be available shortly.

August 30, 2012

Talking with Robyn Young.

Today, I’m delighted to be talking with Robyn Young. Robyn has written a series of novels set in medieveal times, the Brethren Trilogy and the Insurrection Trilogy. Renegade, the third of the Insurrection trilogy has just been published, in fact only yesterday, so get your copy now.

Before we focus on your own writing I would like to look at where it all began.

Who has been the greatest influence upon you as a writer?

Many people have influenced my writing over the years, but I think the first, and perhaps most formative, has to be my grandfather, a gifted storyteller. Some of my best memories come from family holidays at my grandparents’ in Somerset. My cousins and me would gather in the evenings and my grandfather would tell adventure stories where we were the main characters. It was all rather Enid Blyton. I continued the tradition with friends, then on paper. At school an enthusiastic English teacher encouraged me to write poetry. I won several competitions, one of which saw my poem published in a national anthology. I still remember the first time I saw my work in print.

What made you decide to write historical fiction?

That came as a surprise. From poetry and short stories I went on to write articles for a regional newspaper, followed by two fantasy novels. But while my path as a writer seemed set fairly early on, I didn’t imagine I’d be penning history. It wasn’t a subject I did well in at school, or of any real interest to me, until I read a book on the Knights Templar, by historian Malcolm Barber. I’d listened to a conversation between two friends about these so-called warrior monks and my curiosity had been piqued enough for me to pick up this text when I saw it in a bookstore. Barber’s book, a harrowing account of the knights’ downfall, made me realise that history, far from being a set of dusty facts and figures, is a rich collection of stories. He brought the human element to it, which had been missing at school. The moment I finished reading, I knew I wanted to tell their story, which at this point – pre Dan Brown – was still relatively untold.

What’s been your favourite moment in your writing career?

That’s a tough one. You go on quite a ride when you’re first published, especially if you’re lucky enough that your novel does well. I’ve had some incredible moments these past years – seeing my first front cover, then the finished book on a shelf in Waterstone’s. I’ll never forget entering my publishers’ to celebrate the launch, to be handed a glass of champagne and told Brethren had gone into the top ten. Then there’s the very private, but no less triumphant point that you finish a novel – for me usually late at night after the last, long sprint to the final page. But I think the ultimate moment has to be my agent phoning me, at the end of a four-year struggle to get published with many rejections along the way, and telling me that I was going to be a published author.

You studied creative writing at University. What was the best thing about this?

I started with a foundation course in creative writing at Sussex University, where I began writing Brethren, which I’d started researching the year before. I felt so excited, yet so daunted by the prospect of writing a novel (a trilogy, as it turned out) set in such a complex period that I decided I needed the structured support a weekly class could offer. It was so beneficial I went on to do a Masters. There is a sort of stigma attached to creative writing courses – a tendency to believe that it cannot, or should not be taught. But writing is a craft as much as an art and one of the most valuable aspects of both courses for me was the feedback from my peers. One of the hardest, most vital things to learn is how to edit your own work effectively. Working with others, deconstructing one another’s writing, asking the questions you constantly need to ask yourself – why this point of view, what does this dialogue offer, what about pace here, exposition there? – teaches you to see where your strengths and weaknesses lie. Hemmingway called it having a built-in shit detector.

How do you research your novels?

It starts off with book-based research, during which time I write an enormous amount of notes, trying to piece this historical world together. First, I’ll read a selection of texts that cover the broad era, then biographies of my main characters, then I’ll start getting into the finer details, researching what people ate, what they wore, what they believed in, what their homes were like. It’s about building up as full a picture as you can. Even if you don’t use half the things you research, it will come across in your writing as confidence and authenticity. Web-based research is getting better, but I still only use the Internet when I have a good enough grounding myself to know which sites are good, and which aren’t. After the first bulk of reading is done, I try to visit as many of the locations as possible. I speak to historians and re-enactors about specific events or equipment and I like to try my hand at the various physical aspects of my novels. For Insurrection, I was taught to ride by a skill-at-arms tutor. I’ve tried sword fighting, worn armour, used crossbows, done extensive work with birds of prey, all of which have, I believe, added colour beyond the book-based details.

What would be a typical writing day for you? Do you have set times, spaces, routines or rituals?

It seems to go in cycles. Research and plotting tends to be more fluid – I’m usually reading and travelling. When editing I find I can’t be in the same place I write in (my study) – it’s a different headspace and I guess changing the physical space helps that shift. When I’m in the thick of writing I usually work best first thing or late at night. Afternoons tend to be fairly dead times creatively. I try to do a full morning’s work, then do admin or research after lunch, before perhaps going back to writing in the evening if I need to push on. It can get quite intensive towards the end of a book, when aiming for a deadline. In the last five months of writing Renegade I had about four days off.

Could you tell me more about fire-breathing on a café rooftop?

Lol. Yes. I used to organise festivals and ran a nightclub in Brighton, so I spent my early twenties at the heart of the music scene there, when the illegal rave culture was in vogue. One of my friends was a fire-breather and one night (well, dawn) at a rave on Brighton seafront, he taught me how to do it. We climbed up on the roof of a café and spent the next hour swigging paraffin and blowing balls of fire into the sky above the crowd. I was quite lucky really – I remember he lost his eyebrows.

Moorlands or coastland? Coastland

Morning, afternoon, evening or night? Evening

Fire or ice? Ice

Finally, Robyn, what is your current writing project?

I’m working on Book 3 of the Insurrection Trilogy, which is based on the life of Robert Bruce, the second of which, Renegade, is out this month.

In fact, it was published yesterday. Congratulations, Robyn and thanks for talking with me.

You can find out more about Robyn by visiting: www.robynyoung.com

*******************

On September 14 I’m talking with Douglas Jackson.

After that we’ve got Simon Toyne, N. Gemini Sasson, Harvey Black with many more authors in the following weeks.

August 29, 2012

Talking with Gordon Doherty and Myself.

Here are two more extracts from talks with writers. The first is from my talk with Gordon Doherty. The second, to round out the number of extracts, is from an interview I gave to Ty Johnston.

First, Gordon.

Martin: When did you first know that you wanted to be a writer? Was there a specific event that made you decide?

Gordon: Tolon, Greece, summertime 2004: gazing out over the Aegean at dusk, I envisioned a dusk raid by a fleet of triremes. I could see the armoured hoplites dropping onto the shore, I could hear their armour rippling as they rushed across the hinterland and I could sense the fear of those defending, higher up the beach. Then I stopped for a moment and thought; ‘Damn, I miss writing stories. Why did I ever stop?’

In my childhood, as a means of storytelling, I would (badly) mimic my elder brother’s excellent skills as a cartoonist. Then I started to write stories with the odd illustration every few pages. Finally, the pictures disappeared altogether as I turned to traditional short story writing. A misspent youth meant I wrote little more than angst-ridden poetry and songs for many years after that. It was a few years after I eventually settled down into a ‘normal’ career that I reached that epiphany moment in Tolon.

What would be a typical writing day for you? Do you have set times, spaces, routines or rituals?

As soon as I wake up, my mind starts turning over the next chapter, the next plot rework, the next revision. Actually, I’m lucky if I don’t have writing dreams (I did actually have a nightmare about publishing a story where the Roman protagonist had a USB key)! What I’m trying to say is that it’s easy for writing to dominate every heartbeat of your day. So, I try to be disciplined and channel my efforts into ‘blocks’ of writing time. I’ll go into the spare room which doubles as my office, close the door (very important) and set my Pomodoro timer for thirty minutes . . . then I write.

What’s been your favourite moment in your writing career?

Legionary has a dedication to my late aunt. When I gave a copy to my uncle, and saw how much it meant to him, that made all the hard work and long hours worth it.

Finally, here’s a part of my talk with Ty Johnston.

Ty: you write quite a bit of historical fiction. What draws you to such literature? More specifically, you’ve written about English history soon after the Battle of Hastings, so what drew you to that particular period?

Martin: I love history and I love literature. One morning, I had the idea of fusing my two passions and writing historical fiction. About this time I also discovered George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman novels and realised that historical fiction could be a wonderful vehicle. I was drawn to the period after 1066 because I’ve been fascinated by the Anglo-Saxon period since reading a Ladybird book about King Alfred at the age of eight or nine. 1066 was a disaster for ordinary people and I was drawn to writing about a time when their world was broken in this manner. Many people in England still think that the country started when the Normans seized the kingdom, a propaganda coup which has lasted for a 1,000 years.

What do you most hate about your hero?

Tough question. The hero of The Lost King series is Edgar, the young boy who was the rightful King of England and was proclaimed as such just after the Battle of Hastings. He must have been an astonishing man and I look forward to writing about the rest of his life. The one thing which gets me, and I didn’t intend this, is that he is sometimes overawed and overwhelmed by William the Conqueror. It frustrates Edgar as well: “I searched the pennants fluttering above the troops. There, yes there, was William’s standard. It towered above a forest of other flags, arrogant, assured, a spit in my eye. My heart seemed to stall at the sight of it. What hope did we have now that William here?”

You can find the full talks by following the links below.

Related articles

Talking with Gordon Doherty (martinlakewriting.wordpress.com)

http://tyjohnston.blogspot.fr/2012/05...

This Friday I’m talking with Robyn Young.

August 27, 2012

Talking with Angus Donald and James Wilde

Here are extracts from two more of my talks with writers.

First, Angus Donald, author of the Outlaw series about Robin Hood.

Martin: How do you research your novels? Do you do it before you start to write or do you research on an ongoing process?

Angus: Both. I start with a vague idea – for example, in King’s Man (book 3, out in paperback on July 5th) the story is loosely about Blondel, with Alan the trouvere rescuing Richard the Lionheart from imprisonment in Germany. I read a lot about Richard’s time in prison, and his ransoming by the English under the direction of his mother Eleanor of Aquitaine. Then I visited the part of Germany that was relevant to the story, near Frankfurt. Then I started writing. But I do research online along the way. I suddenly realised 40,000 words into the story that Alan (Blondel) would not travel to Germany on horseback as I had originally supposed. Everybody travelled by water on long journeys, if they possibly could, as it was so much easier and safer. So I had to research boat travel on the Rhine a third of the way through the book: what kinds of boats did they go on? How were they propelled? What did they transport as cargo. As I say, it’s a bit of both – there are always details that you need to find out while you are actually writing the story. What day was Easter in that year? What did people do when they had a cold? What colour robes would the monks in this particular monastery wear? That sort of thing. I do that in libraries and online while I’m in the middle of the book.

What would be a typical writing day for you? Do you have set times, spaces, routines or rituals?

I write best in the morning. So my routine is geared to that. I get up around 7-ish, grab a cup of tea, and go up to my study, which is at the top of our very decrepit medieval house. I work in my dressing gown until mid-morning then shower, have breakfast and get dressed. I try to go for an hour’s walk in the Kent countryside before lunch at 1pm with my wife and baby son, Robin. (The other child Emma is usually at school then.) In the afternoons I read, and sometimes take a nap, and I write/edit again from about four till six pm, when I come down and rejoin the family and have tea, or a drink and begin cooking supper for my wife Mary. That is the basic structure of my day – but the pleasure of being self-employed is that I can change it as and when I like.

Next James Wilde: author of Hereward and Hereward: The Devil’s Army.

Martin: Which authors have had the greatest influence upon you?

As a child, Alan Garner changed the way I thought about books. The Weirdstone of Brisingamen and The Moon of Gomrath were phenomenal works of imagination and showed me how the deep past still affected the present. Later I consumed just about everything by the sadly-missed Ray Bradbury, as well as Lord of the Rings. John Steinbeck, Thomas M Harris and Umberto Eco, particularly Foucault’s Pendulum, have all been big influences.

What would be a typical writing day for you? Do you have set times, spaces, routines or rituals?

I’m a disciplined writer. I don’t believe in this airy-fairy, waiting for the muse to arrive. That’s usually an excuse made by people who don’t know how to work for a living. I try to achieve a set word count every day, probably around 2000 words. I remain flexible on the times. I like to begin around 8-ish, but sometimes I feel I’m more productive at night so I tend to go with the flow.

I don’t have set spaces – quite the opposite. Sometimes I’ll write in my study, sometimes in a pub or café, sometimes outside somewhere. I find breaking up the routine minimises boredom and allows for greater concentration which is the key to productivity.

Rituals – I write on a MacBook Pro and always listen to music on earphones when I’m working because it keeps the world at bay.

*******************

You can find the rest of the talks by clicking on the links below.

Next post: extracts from the talks with Gordon Doherty and yours truly.

Related articles

Talking with Angus Donald (martinlakewriting.wordpress.com)

Talking with James Wilde (martinlakewriting.wordpress.com)

August 26, 2012

The Order of the White Feather #SampleSunday #histfic

English: Original Kitchener World War I Recruitment poster. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Constance Sturwood sat beneath a parasol. One could never be too careful. This hot sun will make me look ghastly, she thought. She dabbed a handkerchief to her lips. Her three brothers were playing croquet on the west lawn. Peter and Edward were going easy, letting Willie gain more points than he should. He suspected this but ignored his suspicions; glad that for once he was not being totally annihilated.

Constance sipped her lemonade. Despite the ice chinking in the glass the lemonade was beginning to get warm. She rang the little bell on the table and its clear noise tinkled across the lawn to where Jackson was polishing the cutlery for the dinner-party. He put down a knife and began to make his way towards her. She saw him pause. The boy, Billings, had come into the room and was talking earnestly to him. Jackson took a piece of paper from his hand, read it and stared out of the window. Constance wondered vaguely what might be the problem.

Jackson stepped onto the lawn. He did not, however, go towards his young mistress to see what she wanted. He walked across to the young gentlemen. His pace was not his usual calm tread; he hurried and he seemed agitated.

‘Master Peter,’ he said. ‘I have just learned that we have declared war.’

Peter stood with his mallet resting on his shoulder and stared at Jackson. Edward shook his head as if he did not believe his ears.

‘Hooray,’ cried Willie.

Constance stood up, her chair toppling over onto the lawn. She hurried to her brothers.

‘What does this mean?’ she asked.

‘It means, little sister,’ said Peter with a grin, ‘that Edward and I shall go off to enlist.’

‘What about me?’ cried Willie.

‘You’re too young,’ said Peter. He strode over and plucked up his blazer. ‘Come on Ed,’ he said. ‘Not a minute to lose. We want to be first in line.’

‘Will I get a chance?’ asked Willie.

‘I’m afraid not,’ said Edward. ‘It will all be over by Christmas.’

Constance placed her hand on Willie’s shoulder and watched as her brothers raced off to the motor-car.

Jackson turned towards her. ‘I believe you rang, Miss.’

‘Yes.’ She ran her fingers through her hair. ‘I wanted some ice. But it doesn’t seem to matter now.’

‘I shall bring it immediately.’

‘It’s not fair,’ said Willie. ‘I’m sixteen. I’m old enough to fight.’

‘You’re still at school,’ Constance told him.

‘But Edward’s at Cambridge.’

Constance gave him an exasperated look. It was lost on him because at that moment he spotted his father striding towards him.

‘Father,’ Willie cried. ‘We’ve declared war on France.’

‘Not France. Germany.’ He turned towards Constance. ‘Where are Peter and Edward?’

‘They’ve gone to the village. To enlist.’

His hand went to his mouth. He stared at her in silence. She saw his eyes moisten. He nodded and walked towards the house.

Three days later, Constance’s best friend Dora, called.

‘They say it will be over by Christmas,’ Constance said as she poured Dora a cup of tea.

‘That’s not what Lord Kitchener thinks,’ Dora said. She pulled out a leaflet asking for volunteers. ‘My Uncle Claude, the colonel, says that Lord Kitchener thinks it will last three years.’

‘That’s ridiculous.’

Dora shrugged. ‘Well it’s made a few of us girls decide that we should do our bit.’

‘In what way?’

‘By encouraging all the young men to enlist. I’ve persuaded three already. Are you game for it?’

Constance opened her mouth to answer but could not find any words. She wondered what her father would think of it. She thought of Peter and Edward who had already enlisted. She realised that Dora was still talking.

‘And if it lasts three years then boys like Willie will be able to do their bit.’

‘No,’ said Constance. ‘He’s just a child.’

Dora shrugged and sipped her tea.

‘I’ve persuaded three and Edith and Jane have persuaded two. If you want to take part you’d better get your skates on.’

Constance thought about how keen her brothers had been to do their bit. And Willie. Even Willie wants to go and fight. She frowned. If enough men joined up now then maybe he wouldn’t have to.

‘It’s only right,’ said Dora. ‘It’s for King and Country.’

‘You’re right,’ said Constance. ‘I’m game for it.’

************

This story is the first of three stories about World War 1 in my collection ‘For King and Country.’

The stories focus on the Home Front, life in the trenches and in an observation balloon. It is available from all e-book retailers.

August 25, 2012

More of my Talks with Writers: SJA Turney and Lynn Shepherd

Over the summer I had a series of talks with authors. The series is starting again on 31 August with a talk with Robyn Young, an author of historical fiction.

Before then, I’m posting extracts from my earlier talks. I’vealready posted from the ones with David Gaughran and Ty Johnston and will follow this with extracts from Angus Donald, James Wilde, Gordon Doherty and, to make the round half dozen, an extract from an interview which I gave earlier about my own fiction.

First, here’s an extract from my talk with SJA Turney

Martin: When did you first know that you wanted to be a writer? Was there a specific event that made you decide?

Simon: I used to write short stories as a teenager, and even poetry for a time. That waned, though, as I went to university and then left, finding myself in an unforgivingly dull and grey job market. I worked as many things over the next decade, never truly settling into anything. My writing began partially as an experiment, to see if I still had anything of the bug, and partially through the sheer ennui and boredom I suffered in my excruciating job at the time. It was only as I finished writing Marius’ Mules in my spare time that I realised just how much I enjoyed it and how much I wanted to keep doing it

Martin: You write historical fiction. Why this genre in particular?

Simon: I write historical fiction, though I have also delved into the world of ‘historical fantasy’ with my Tales of the Empire series. In all cases, though, the Roman theme is prevalent in some form or other. I have had an unquenchable fascination with the world of Rome since the age of six, when my grandfather (the wisest person I ever knew) took me to Hadrian’s Wall and I stood on the wall of Housesteads fort, staring off into a blizzard. Since then I have travelled to every Roman site I can reach at any given opportunity, and read extensively into the history of that fascinating world.

Next, a couple of answers from Lynn Shepherd

Martin: What made you choose to write your modern take on classic novels? Did you have any worries about tackling characters who would be greatly loved by readers?

Lynn: The initial idea for turning Jane Austen into a murder mystery just popped into my head unbidden in the summer of 2008. I had no idea or intention at that stage of doing the same thing again. But once Murder at Mansfield Park was published I started to wonder whether I was onto quite an interesting and unusual idea. After all, there are many murder mysteries set in the Victorian period (some of them very good), but no-one’s done quite the same thing as I’ve done in Tom-All-Alone’s (which is published in the US as The Solitary House). In other words, creating a new story that runs parallel with another book – in this case Bleak House. And yes, there’s always a risk if you work with a classic that people love, but I think most people who’ve read my novels can see that I love those classics just as much as they do, and have written my own books in that spirit.

Martin: How do you research your novels? Do you research before you start to write or do you do it on an ongoing process?

Lynn: There was much more research for Tom-All-Alone’s/The Solitary House than for Murder at Mansfield Park. For the Austen, most of the work went into getting the language right; for the Dickens, it was a much bigger task, because I had to bring Victorian London back to life. That meant a lot of reading. Though in principle I always do the minimum of research before I start writing and fill in the gaps afterwards, because otherwise you can fall into the trap of having the research dictate the story, rather than the other way round. I hate it when I read books and stumble over huge lumps of only partially digested research which the writer’s obviously spent days looking for, and is going to get in there one way or another!

You can find the complete talks by clicking on the links below.

Related articles

Talking with S.J.A. Turney (martinlakewriting.wordpress.com)

Talking with Lynn Shepherd (martinlakewriting.wordpress.com)

August 24, 2012

The Emperor’s Spy by MC Scott.

This is an excellent historical novel, one which blends character driven narrative with tightly plotted action. It is easy to let either action or character dominate the other; MC Scott avoids this by peopling her novel with a range of vibrant characters placed in dread peril.

I was intrigued that one of her central characters is a young boy of about the same age as Edgar, my protagonist in The Lost King, with all the opportunities which this gives to engage the reader. Math is a wonderful creation who will live long in my memory.

I loved many things about this book. One is that people of different ages play key roles whether young like Math or old like Shimon and Seneca. The other is that there are strong female characters. They are tough-minded, sensitive and sensual and move the plot and the world of the book. I hope to see more of Hannah in particular in future novels.

Scott’s writing is sensual and alluring. As I read the book I was thrown into the furnace heat of Alexandria and the fetid stews of Rome: ‘…the dawn mist rising from the river draped itself wetly over the stalls, saturating them all in the Tiber’s bouquet of drowned rats and duck shit and mud.’

She is also adept at the telling and insightful phrase: ‘His bare feet were hard as hooves from a lifetime’s unshod wanderings.’ Lovely writing.

There were a few occasions when I felt the characters placement in a scene was stretching the probable, serving the plot rather than the milieu or the characters’ motivations but these were few.

I most especially liked the way in which much of the conflict was not about warfare and fighting, although there was plenty of that. There was competition between chariot racing teams, fighting to master wilful horses, exhausting battles against immense fires, the clash of different beliefs and the conflict of loving too many people. Real conflicts which churned my heart and caused me tears.