Rachel Held Evans's Blog, page 44

April 5, 2013

The Absurd Legalism of Gender Roles: Exhibit C – “As long as I can’t see her…”

Exhibit A: The black belt should step aside (because she’s a girl!)

Exhibit B: Boys playing with dolls unravels the moral fabric of society

Exhibit C: A woman can teach me as long as I can’t see herScot McKnight was the first person to draw my attention to the fact that “anyone who thinks it is wrong for a woman to teach in a church can be consistent with that point of view only if they refuse to learn from women scholars” (The Blue Parakeet, p. 148). And it was Scot who, on his blog this week, pointed his readers to a podcast interview in which John Piper responds to the question, “Do you use commentaries written by women?”

(So before anyone criticizes me as being a "shrill," "irrational" woman picking on John Piper, please remember that Scot has been discussing this for several years as well.)

Now, in the past, we’ve discussed the sort of hermeneutical gymnastics involved in John Piper’s bizarre, half-hearted affirmation of Beth Moore as a teacher, and we’ve discussed, at length, the context of 1 Timothy 2 and why it should not be used to silence women from preaching the gospel and leading in the church.

Today I want to look at Piper’s response to this question about commentaries written by women to show just how absurd the legalism of hierarchal gender roles can become.

Ironically, Piper’s primary measure of appropriateness is whether a man feels threatened by a woman’s teaching. This is something you will hear from time to time from this camp: when in doubt, it all comes down to the degree to which a man senses he is maintaining his authority. As long as the men still feel in control, some degree of teaching from women may be permissible.

But what about men like my husband, or my pastor, or Scot, who are not threatened by the intelligent, thoughtful contributions of women in leadership? What about men who enjoy and appreciate partnerships with women and whose sense of calling and security is not dependent upon my subjugation? Why enforce these roles onto them?

As Dan has told me on many occasions, for him, it is far less insulting to be under the authority of a woman than it is to be subjected to the suggestion that his fragile ego cannot handle it. “I’m just not that insecure,” he likes to say. “Learning from a woman doesn’t make me feel like 'less of a man.' Why would it?”

Piper argues that a woman can teach a man so long as her teaching is “impersonal,” “indirect,” and “removed”—essentially, so long as it is easy for him to forget she is a woman.

Regarding a woman who has written a biblical commentary, he explains: “She’s not looking at me, and directing me…as woman. There is this interposition of this phenomenon called ‘book’ that puts her out of my sight and, in a sense, takes away the dimension of her female personhood, whereas if she were standing right in front of me and teaching me as my shepherd…I couldn’t make that separation" (emphasis mine).

As a woman, I find this profoundly dehumanizing. No, as a human being, I find this profoundly dehumanizing.Piper is essentially arguing that so long as he does not have to acknowledge my humanity, so long as I keep a safe distance so he is unaware of the pitch of my voice and the presence of my breasts, he can, perhaps, learn something about the Bible from me. So long as I am not “in-his-face” (his words) with my femaleness, it will be easier for him to treat me as someone worth learning from; it will be easier for him to treat me like a man.

How are women to interpret this as anything other than a statement on the inherent inferiority of their natures? What else are we to conclude when a man without any biblical training or calling from the Spirit is considered more qualified to preach the gospel by virtue of being a man than a woman with extensive training, years of practice, remarkable giftedness, and a profound sense of calling? Is this not legalism? Is it not straining a gnat and swallowing a camel?

And what on earth is Piper to do with women like Priscilla, who the apostle Paul lauded as one of his coworkers, and whose teaching of Apollos was both direct and personal? What about Huldah, the prophet? Did King Josiah close his eyes so he would forget she was a woman as she read and interpreted Scripture in his presence, explaining, directly and personally, how that Scripture would affect Israel and its king? And what does Piper do with Deboarah, a woman who essentially took on the role of drill sergeant he is so keen to avoid (not to mention judge, warrior, and commander-in-chief), and is celebrated in Scripture for doing so?

This is the absurd legalism of gender roles: Not even the Bible’s most celebrated women can fit into them.I’ll conclude with some words of encouragement from Dorothy Sayers. (Men who would be offended by hearing this from her in person will be happy to know she is dead and her words are safely tucked away in an essay entitled “Are Women Human?”)

"Perhaps it is no wonder that the women were first at the Cradle and last at the Cross. They had never known a man like this Man—there never has been such another. A prophet and teacher who never nagged at them, never flattered or coaxed or patronized; who never made arch jokes about them, never treated them either as ‘The women, God help us!’ or “The ladies, God bless them!’; who rebuked without querulousness and praised without condescension; who took their questions and arguments seriously; who never mapped out their sphere for them, never urged them to be feminine or jeered at them for being female; who had no axe to grind and no uneasy male dignity to defend; who took them as he found them and was completely unselfconscious. There is no act, no sermon, no parable in the whole Gospel that borrows its pungency from female perversity; nobody could possibly guess from the words and Jesus that there was anything ‘funny’ about woman’s nature."

"But we might easily deduce it from His contemporaries, and from His prophets before Him, and from His Church to this day. Women are not human; nobody shall persuade that they are human; let them say what they like, we will not believe, though One rose from the dead."

Perhaps we could push beyond these legalistic gender roles if we spent less time worrying about “acting like men” and “acting like women,” and more time acting like Jesus.

[Latter we'll look at Exhibit D, in which women are advised not to work outside of the home, even if it's more practical for their family.]

For more on 1 Timothy 2, see: "For the Sake of the Gospel, Let Women Speak" See also, "Is Patriarchy really God's dream for the world?"

Please keep the comments civil!

April 4, 2013

Are we there yet?

Today I am pleased to introduce you to Jeff Chu. Jeff is the author of Does Jesus Really Love Me?: A Gay Christian's Pilgrimage in Search of God in America—a fantastic book that is part-memoir, part investigative analysis. The book, which just released last week, explores the intersection of faith, politics, and sexuality in America in a way that is thought-provoking, well-researched, colorful, and deeply personal without being indulgent. I highly recommend checking it out.

Over his eclectic journalistic career, Jeff Chu has interviewed presidents and paupers, corporate execs and preachers, Britney Spears and Ben Kingsley. As a writer and editor for Time, Conde Nast Portfolio, and Fast Company, he has compiled a portfolio that includes stories on megahit-making Swedish songwriters (a piece for which he went clubbing in Stockholm); James Bond (for which he stood on a Spanish beach and watched Halle Berry emerge from the waves over and over and over); undercover missionaries in the Arab world (he traveled to North Africa and went to church); and the decline of Christianity in Europe (he prayed). On the wall of his New York office, you'll find a quote from former Senator John Warner, who once told Jeff: "You're a good little interviewer!" A California native, Jeff went to high school at Miami's Westminster Christian, where he sat behind Alex Rodriguez in Mr. Warner's world history class. A graduate of Princeton and the London School of Economics, Jeff has received fellowships from the Phillips Foundation and the French-American Foundation, and in 2012, was part of the Seminar on Debates in Religion and Sexuality at Harvard Divinity School. The nephew and grandson of Baptist preachers, he is an elder at Old First Reformed Church in Brooklyn, New York. He loves the San Francisco 49ers, the Book of Ecclesiastes, and clementines. And he detests marzipan more than he can explain in words.

I hope you enjoy this post as much as I did.

Are we there yet?

By Jeff Chu

“Jesus will not accept you, because of your hard heart and hate for him.”

“We must treat homosexuals like those suffering a mental disorder, because that is exactly what it is. If anything, we should have pity on these people.”

“You need a good ex-gay therapist.”

Last week, messages like these filled comments sections of websites where my writing was being discussed. On Facebook, I was informed that I was clearly not saved. My inbox brought warnings that I needed to repent.

I interviewed more than 300 people for my book, but intertwined with their stories is my own. I’ve never written about my life or my faith before, and naively, perhaps, I didn’t expect this onslaught. The night before my book came out, I sat at my desk in my office and did something that I haven’t done in years: I wept.

For almost an hour, the tears rained down my face. I held my head in my hands, and I shook. Then, inside, I heard the softest echoes of my beloved late grandmother’s warbly voice, speaking to me in Cantonese as she had when I was 8: “You’re a big boy. Don’t cry. Big boys don’t cry. Crying doesn’t do anything.”

Well, this big boy does cry—and on that day, it did do something. These were, at first, tears for fears—fears of being judged, fears of being condemned, fears of what might happen when the world saw me, through my book, for who I was and no longer for who I’ve long tried to be.

Then they became tears of grief. In some ways, I felt as if I were being excommunicated from my church—these messages all came from people who would place themselves in the evangelical part of the church that I grew up in. But in truth, they couldn’t kick me out. In soul and spirit, I’d already left those precincts of the church, and I was belatedly mourning that departure. I was also weeping for the loss of certainty—or at least the illusion of it that I once worked so hard to maintain.

***

When I was a young journalist, I was taught to “kill your darlings.” Sometimes we writers will concoct a pun or a phrase that we just fall in love with. Applaud your own unparalleled cleverness, your unmistakable wit, I was told. Then cut what you just wrote. Your infatuation is also often the enemy of clarity—and sometimes truth.

One thing I had to mourn last week was the killing of perhaps my greatest darling: the persona of the Good Christian I long maintained, under the theory that it could somehow help preserve my faith.

This is, of course, a fallacy: Sometimes we speak as if our faith—and the faith—is unchanging. God may not change, but our beliefs and our understanding of Him do. Faith can’t be preserved, as if it were strawberries in jam or an unlucky beetle in ancient amber. It’s dynamic. It struggles and stumbles, waxing and waning, colored by circumstance, shifted by our spirits, and shaped (we hope) by the Spirit. I think, for instance, of Roman Catholicism, and how the Virgin Mary officially became retroactively and posthumously sin-free in the 19th century. And I think of the denomination I grew up, the Southern Baptist Convention, whose own less-than-immaculate conception was rooted in unfortunate disagreements with their northern brethren over slavery.

For a long time, I resisted change. Though I felt alienated from the church and culture of my childhood, I played the image game well. I was treasurer of my college evangelical-fellowship group. I mentored younger students, my mouth saying things with far more surety than my heart ever felt. I even had a (shortish) string of long-term girlfriends—wonderful, godly women who, thank God, found much more suitable men to marry.

My semblance of pious normality reflected a Sunday-best mentality spilling over into the rest of the week. I thought that if, perhaps, I did a goody-goody-enough job with the façade, maybe it would percolate into the rest of me, preserving my faith. On some level, I guess I naively thought that I might even be able to fool God.

I had to kill that person, that darling. I had to stop lying. And when I cried, I guess some of the tears were for that old Jeff. That costume, more comfortable than I’d like to admit even now, was a great hiding place, a cocoon that I convinced myself was safe. It was a big game of pretend, and I was pretty good at it, except that all games get old—or maybe you just get too old to play them.

***

A church of costumes and hiding places isn’t a place I want to be.

What we need, more than ever, is a church where we can shed the pretenses, and bring our doubts, our big questions, and our bigger fears. I don’t think I’m alone in desiring that. What I suspect many of us crave is a church where we can be our whole, ugly-beautiful selves.

This is who I really am: I am not an issue. I am a follower of Jesus. I love my husband like you love your husband. Sometimes I daydream during church, which I feel especially guilty about now that I am an elder. I am afraid to go to India because I don’t know if I am man enough to handle that much poverty in my face. I like to load the washer, but I’m terrible at unloading the dryer. I am really judgmental. I use the F-word a little too much. Sometimes, if I find a very old French fry, I will be tempted to eat it. (I will neither confirm nor deny that I ever have.) I love the Bible, and I believe that sin is a real thing, but I wish I understood better what God meant by it. I went to a Taylor Swift concert last week—for my job—and enjoyed it more than I’d like to admit. I need a good editor.

And who are you? Maybe you laugh too loudly. Or you cry too much. You love, even though you’re not always sure how to show it. You belch when you think nobody is listening. You love justice, but you’re not always sure what it looks like. You question your pastor. You watch too much Honey Boo Boo (which is to say, you watch it at all). You lie awake in bed some nights wondering whether God is as real as you want Him to be. You eat too many meals in your car. You say, “Bless her heart,” when you have no intention of blessing any part of her.

Can we be these people in church? We must be—and the church that I’m talking about is not a building but the collection of the people who are trying their best to walk with Jesus. It does not end at 12:15 on Sundays. It’s wherever we and our hopes and our complicated, messy lives are. It’s a place where we aren’t afraid to say, “I don’t know.”

Our church is a place where we’re unafraid to acknowledge that we’re always in beta. I was thinking about this during church this past Sunday. In his Easter sermon, my beloved pastor, Daniel Meeter, encouraged us to imagine “the life of the world to come … Imagine always trusting other people, without having to be careful, always being open and candid about yourself without having your guard up, and even knowing yourself with clarity and honesty and peace,” he said. “Well, you are not there yet.”

Indeed.

Maybe I’ll end up in hell. Maybe I do have a mental disorder. Maybe their Jesus won’t accept me. But I still cling to a Jesus who will meet me—and will meet us all—where I am now. Can we build a church that welcomes our mutual strengths but also allows—and even embraces—our confessions of weakness? Can we be that community? Will you join me on this journey?

***

You can follow Jeff Chu on Twitter. And be sure to check out Does Jesus Really Love Me? which released last week!

April 3, 2013

When it comes to controversy, avoid these two extremes...

In “real life,” when you have new friends over for dinner, you don’t usually begin by passing the potatoes and asking about their views on gay marriage. (If you’re at my house, we at least wait until dessert!)

But online, we get right to it. Whether it’s through a Facebook status, a blog post, or a tweet, we shout our thoughts from virtual rooftops, where they are met with questions, affirmations, pushback, or outrage.

I believe both forms of communication are important and can be life-changing. In my travels, as I’ve met so many of you face-to-face, I’ve come to see that “real life” and “online life” should not be regarded as separate spheres, but as connected. I’ll never forget the church that beautifully integrated words from my blog posts into their liturgy one Sunday morning, or the painter who rendered a chapter from my book into art, or the young man who composed a song around this post, or the pastor who made last-minute adjustments to his Easter service to ensure that women had a voice in proclaiming the resurrection, or the church that changed its policies regarding abuse because of our series on the topic, or those of you who have sponsored children, worked the blessing of “eshet chayil!” into your life in creative ways, or finally had that breakthrough conversation with your gay son or daughter— all because of conversations we’ve had here on the blog. I am especially grateful for the ways in which online dialog has helped bring the issue of gender equality in the church back to the forefront, sparking a wave of new writers, new publishing deals, and new perspectives every day.

It is precisely because words have real-life consequences that, occasionally, a post or a speech or even a tweet is regarded as controversial among Christians. Since I write fairly often on the topics of gender, doubt, the Church, and biblical interpretation, I’ve been through my fair share of controversy within Christian circles, and in those experiences, I’ve noticed two extreme responses that I think we should avoid:

1. “This is controversial, so it MUST be wrong.”This response is often generated in the name of preserving Christian unity.

In my experience, it goes like this: Someone writes something at the Gospel Coalition or Desiring God about the importance of preserving hierarchal gender roles in the Church. I write a post outlining my disagreements with that position. People on both sides weigh in, and things get a little heated. I get a bunch of angry or tearful emails about how I’m sowing disunity in the Church and how “The Enemy” must be loving every minute of this because all this controversy is ruining our Christian witness to the world. I should have left well enough alone.

Now, I absolutely believe that Christian unity is important, and I would break the bread of communion in a heartbeat with folks like Mark Driscoll or John Piper whose views on gender roles I oppose. But unity does not mean uniformity. And while some controversy may in fact indicate unhealthy friction; it is just as common for controversy to indicate the sort of healthy friction that emerges from positive change.

The early Church was not without controversy, precisely because of all the uncomfortable change associated with bringing together Jews and Gentiles, slaves and free, male and female, rich and poor, as partners in experiencing and sharing the Gospel. One thing I love about the epistles of Scripture is the way in which the writers negotiate these tensions without calling for absolute agreement, but instead calling for absolute love in the midst of disagreement.

A brief survey of history reveals that controversy within the Church often arises during times of social, political, and scientific change. Was Martin Luther King Jr. “sowing disunity” when he wrote his powerful, piercing letter to fellow clergy from the Birmingham Jail?

I have found that the response, “this is controversial so it MUST be wrong” is most effectively invoked by those with an interest in preserving the status quo. Those most threatened by calls for change are those who benefit from things staying as they are, so look out for people in positions of power who dismiss any sort of dissent or disagreement as troublemaking. (Sometimes things indeed need to stay as they are, but sometimes things need to change.)Of course, for controversy to be helpful and productive, it must emerge from conversations that are fair, reasoned, charitable, and thoughtful, not from conversations that involve vague accusations or personal attacks. (More on this at the end of the post.) But controversy does not necessarily indicate an absence of the Spirit. In fact, sometimes it indicates the presence of the Spirit.

2. “This is controversial, so it MUST be right.”On the other hand, folks embroiled in constant controversy can also fall into the trap of overconfidence.

Sometimes folks will encourage me by saying, “You’ve generated a lot of controversy; you must be doing something right!” While there is certainly some truth to this, (if you take a stand on anything, you will likely face criticism), we have to be careful of taking it too far by assuming that any pushback or disagreement we receive is an indication of our righteousness.

Christians often frame this in terms of persecution. A pastor will assume that the negative responses to a controversial statement he made in a sermon or through a Facebook status cannot possibly be worthy critiques of his position, but rather the kind of “persecution” Christians can expect to receive for saying and doing the right thing. (Note: Being uncomfortable is not the same as being persecuted, but that’s a topic of another day!) So he refuses to entertain the idea that any of his critiques might have a point, and instead interprets any pushback as only further confirmation of his rightness.

This is an unhealthy attitude toward controversy because it closes us off to constructive criticism. The reality is, an overwhelmingly negative reaction from readers/parishioners/friends may in fact indicate a misstep or mistake. This is why I created an entire category for apologies and corrections. Because sometimes I’m wrong, and often you guys are the first to correct me on it!

This is not to say I’ve mastered the art of responding well to healthy, constructive criticism. I haven’t. But I’m learning, from experience, that just as pushback doesn’t automatically mean I’m wrong, it doesn’t automatically mean I’m right.

Some Guides:So how do we know when the controversy we’re generating is healthy and when it’s unhealthy?

There’s no formula, but there are some good guides to help us as we navigate these waters:

First, I recommend surrounding yourself with a group of friends and family you respect and trust, and when you find yourself embroiled in controversy, ask them for advice and guidance. Those who know you best will know when you have veered off course. And if someone you really respect (including a reader or a fellow writer) is offering pushback, it’s best to suck up your pride and listen because they probably have a point.

Second, check your privilege. If I’m writing about homosexuality, for example, I make an effort to consult with LGBT folks ahead of time, and I try to remain especially open to their advice, perspective, and critiques as I venture into territory with which they are much more familiar than I. As a white, Western, middle-class woman, I enjoy some privileges that others do not, and I am often blinded by my own cultural assumptions and biases. Realizing this has convicted me to listen more carefully to the input and critiques of those whose ethnicity, orientation, background, or life experiences are different from my own…especially if these voices are coming from the margins, from the “outliers.” If you are a blogger, be especially open to guest posts, interviews, and book discussions when tackling topics like abuse, mental illness, gender issues, homosexuality, poverty, and injustice...because some stories just aren't yours to tell. But you can use your platform to give someone else the chance to tell theirs. Also, if you are a man writing about women’s roles in the home and Church, please, for the love, at least entertain the idea that you might not know exactly what it's like to be a woman.

Third, fight fair. For tips on this, I recommend checking out an older post, “How to write a controversial blog post with no regrets.” There I talk about the importance of keeping critiques specific, avoiding personal attacks, watching your tone, and waiting before responding to a conversation that elicits an emotional response. I’m still learning, and I still make mistakes, but these principles have helped out a lot.

***

No doubt you have experienced one or both of these extremes: “This is controversial, so it MUST be wrong!” or “This is controversial, so it MUST be right!” How have you responded to them? How have you been complicit in them? How can we better avoid them?

April 1, 2013

What I learned turning my hate mail into origami

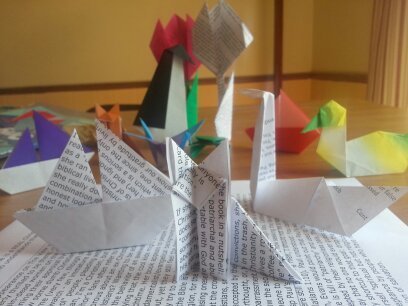

For Lent this year, I wanted to learn a new creative skill that would enable me to turn something ugly into something beautiful, so I resolved on Ash Wednesday to turn some of my hate mail into origami.

As I wrote back in February, “it felt a little awkward at first, but as I moved my fingers across those painful words, folding them into one another to make wings, then a neck, then a crooked little beak, healing tears fell, and I let my fingers pray.”

I’ve been making origami off and on for forty days now, letting my fingers pray out little swans and sailboats and flowers and foxes, and I’ve learned some things: about reverse folds and crimp folds, about trial and error, about patience, about retracing steps and following directions, about forgiveness, about letting go, about redirecting some of my anxious and self-focused energy into purposeful acts of creativity and healing, about building bridges, about asking for help.

That last one—asking for help—turned out to be the most instructive part of them all.

The consummate contemplative, I had originally imagined this Lenten practice to be a solitary one. It would be all quiet and meditative and poetic and introspective.

But it was my friend Melissa who mailed me the origami books.

It was my brother-in-law Tim who helped me make my first sailboat.

It was my friend Monika who sat at my kitchen table and made blackout poems out of the most hateful letters, spending Holy Saturday—our special day—forming crooked little pelicans, ducks, and penguins out of scraps of paper.

It was a reader’s idea to work some beautiful, affirming words into the process too, inspiring me to scribble the prayer of Teresa of Avila and the fruit of the spirit onto the colored origami paper.

It was my sister who made the jumping frog while we waited for Easter dinner.

It was Dan who managed to make the perfect origami crane in a matter of fifteen minutes….

…while I only managed to make this:

It was the author of one of those letters who emailed an apology, upon learning about my Lenten practice.

It was that email that inspired me to issue a few apologies of my own, to be just a little quicker to listen, slower to speak, and slower to get angry.

What I learned turning my hate mail into origami is that we’re meant to remake this world together. We’re meant to hurt together, heal together, forgive together, and create together. Far from being be all quiet and meditative and poetic and introspective, this practice turned out to be full of laughter, cluttered tables, shared grumbles of frustration, and shared exclamations of delight—“That totally looks like a flamingo!”

And in a sense, even the people who continue to hate me and call me names are a part of this beautiful process. Their words, carelessly spoken, spent the last 40 days in my home— getting creased and folded, worked over, brushed aside to make room for dinner, stepped on by a toddler, read by my sister, stained with coffee, shoved into a closet when guests arrive, blacked out, thrown away, turned into poems, and folded into sailboats and cranes and pigeons that now sit smiling at me from my office window.

Because I am a real human being, living a very real life, with a very real capacity to be hurt, to be loved, to heal, and to forgive.

And so are my enemies.

And something tells me we would all be a little more careful, a little more gentle, if we knew how long our words linger in one another’s lives, if we imagined those words sitting on one another’s kitchen tables, shaped like foxes.

Something tells me we would all be a bit slower to speak if we knew just how long it takes to work those ugly, heavy words into something beautiful, something that can float or fly away.

‘Washed and Waiting,’ Chapter 3: “The Divine Accolade”

Today we pick up our yearlong

series on Sexuality and The Church with a final discussion around Wesley Hill’s

short book, Washed and Waiting: Reflections on Christian Faithfulness

and Homosexuality.

Wesley’s

book is meant to both complement and contrast Justin Lee’s book, Torn: Rescuing the Gospel From the Gays-vs-Christians

Debate, which

served as a starting point for our discussion. Both Justin and Wesley are gay,

but whereas Justin concluded that a relationship with another man could be

blessed by God, Wesley has chosen celibacy. I picked these two books

because I think Justin and Wesley represent the very best in civil, gracious,

and loving disagreement on this issue…which for them is not a mere issue, but a

deeply personal journey with deeply personal implications. I highly recommend

reading these books together.

You can check out every post in our series thus far here.

***

Chapter 3 – The Divine

Accolade

In Chapter 3, Wesley explains

that many gay Christians like himself struggle with a sense of shame. It is “a

sense of brokenness,” he says, “the shame of feeling ‘this is not the way it’s

supposed to be’ with my body, my psyche, my sexuality.”

“Sometimes I feel that no

matter what I do, I am displeasing to God,” he recalls telling a friend. “Even

after a good day of battling for purity of mind and body, there is still the

feeling, when I put my head down on the pillow at night to go to sleep, that

something is seriously wrong with me, that something’s askew.” (134)

“For many homosexual

Christians,” he says, “this kind of shame is part of our daily lives.

Theologian Robert Jenson calls homoerotic attraction a ‘grievous affliction’

for those who experience it, and part of the grief is the feeling that we are

perpetually, hopelessly unsatisfying to God.” (137)

Wesley writes that, for him,

much of this shame was lifted when he encountered C.S. Lewis’ essay “The Weight

of Glory”—a literary reflection on the moment when God glorifies his people,

when followers of Jesus hear God declare, “Well done, my good and faithful

servant.”

Summarizing Lewis, (and

referencing Scriptural passages such as 1 Corinthians 4:5, 2 Corinthians 10:18,

Romans 2:29, John 5:44, and 1 Peter 1:7), Wesley writes that “pondering this

future glory…has implications for how we think about our lives now. God’s acceptance

of us in the future, his being pleased with us, means that we may be pleased

with ourselves in the here and now as we live our daily Christian lives; or,

more precisely, we may be pleased that we are pleasing to God…According to

Lewis, the promise of a future accolade from God means we can be satisfied with

our work—our lives, our imperfect efforts to serve and love God—now.” (p.

140-141)

Sure, there is a sense in

which the closer we get to God the more obvious and glaring our sins become.

But the image of guilty, worthless creatures is simply not a pervasive one in

the New Testament, Wesley observes.

“The whole tenor of the New

Testament is strikingly positive when it comes to describing the Christian

experience of trying to live in a way that pleases God,” writes Wesley. “Not

triumphalistic, but positive. Maybe even optimistic. In short, rotten fruit

isn’t the right analogy…The human heart that has been redeemed by Christ has

been made new. And that heart leads to a new way of life. And that way of life

will be honored when Jesus appears on the last day with a ‘weight of glory,’ a

divine accolade.” (p. 144)

What does this mean for

Wesley, a gay man whose convictions have led him to choose celibacy?

“My homosexuality, my

exclusive attraction to other men, my grief over it and my repentance, my

halting effort to live fittingly in the grace of Christ and the power of the

Spirit—gradually I am learning not to view all of these things as confirmations

of my rank corruption and hypocrisy. I am instead, slowly but surely, learning

to view that journey—of struggling, failure, repentance, restoration, renewal

in joy, and persevering, agonized obedience—as what it looks like for the Holy

Spirit to be transforming me on the basis of Christ’s cross and his Easter

morning triumph over death. The Bible calls the Christian struggle against sin

‘faith’ (Hebrews 12:3-4; 10:37-39). It calls the Christian fight against impure

cravings ‘holiness’ (Romans 6:12-13, 22). So I am trying to appropriate these

biblical descriptions for myself. I am learning to look at my daily wrestling

with disordered desires and call it ‘trust.’ I am learning to look at my battle

to keep from giving in to my temptations and call it ‘sanctification.’ I am

learning to see that my flawed, imperfect, yet never-giving-up faithfulness is

precisely the spiritual fruit that God will praise me for on the last day, to

the ultimate honor of Jesus Christ. (p. 145-146)

Questions for Discussion

As we wrap up our discussion

around this book, I’d love to hear your thoughts on Wesley’s perspective. What

did you learn from this book? Did it change you in any ways? What did you find

encouraging/ discouraging/ provocative/ frustrating?

And, again, I’d like to raise

the question I raised last week: Do you think it is possible to fully support both Justin in

his pursuit of a partnership/marriage to another man, and Wesley, in his

decision based on his convictions to remain celibate? Or does the full support

of one somehow diminish the support of the other?

Moving Forward…

Moving forward with the

series, I’d like to spend just a few more weeks focusing on the specific topic

of homosexuality, before we move into other aspects of human sexuality, like

singleness, “purity,” sexual ethics, marriage, and so on. So at least until May, expect Mondays to

include a few more interviews, guest posts, reflections, and book reviews on this topic.

(If you want to read along,

we’ll touching on the following books/essays: Does Jesus Really Love Me? by

Jeff Chu, Our Family Outing by Joe Cobb and Leigh Anne Taylor, A Time to

Embrace by William Stacy Johnson, “The Body’s Grace” by Rowan Williams, The End

of Sexual Identity by Jenell Williams Paris, and a few more.)

March 29, 2013

Mary Magdalene, The Witness

I’ll be taking the weekend off to observe Good

Friday, Holy Saturday, and Easter. This reflection on Mary Magdalene is from A

Year of Biblical Womanhood. For more stories like this one, check out last

year’s Women of the Passion series.

***

Mary Magdalene went to the disciples with the news:

“I have seen the Lord!”

—John 20:18

The story of how Mary Magdalene became known as a

prostitute is a complicated one.

One of six Marys that followed Jesus as a

disciple, she was distinguished from the others through identification with her

hometown of Magdala, a fishing village off the coast of the sea of Galilee.

According to the gospels of Mark and Luke, Jesus cleansed Mary of seven demons,

(a backstory infinitely more complicated and mysterious than prostitution, if

you ask me), after which Mary became a devoted disciple, mentioned by Luke in

the same context as the twelve, who traveled with Jesus and helped finance his

ministry.

In 597 pope Gregory the Great delivered a homily on

Luke’s gospel in which he combined Mary Magdalene with Mary of Bethany

(Martha’s sister), suggesting that this Mary was the same woman who wept at

Jesus’ feet in Luke 7, and that one of the seven demons Jesus excised from her

was sexual immorality. The idea caught on and was perpetuated in medieval art

and literature, which often portrayed Mary as a weeping, penitent prostitute.

In fact, the English word maudlin, meaning “weak and sentimental,” finds its

derivation in this distorted image of Mary Magdalene. In 1969, the Vatican

formally restated the Gospels’ distinction between Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany,

and the sinful woman of Luke 7, although it seems Martin Scorsese, Andrew Lloyd

Webber, and Mel Gibson have yet to get the message.

A cynic might suggest that this mistake and its

subsequent popularity represent a deliberate attempt to typecast and discredit

a woman whose role in the gospel story is so critical and so revolutionary that

the eastern orthodox Church refers to Mary Magdalene as equal to the apostles.

Although she appears to have been a critical part

of Jesus’ early ministry, Mary Magdalene’s extraordinary faithfulness shines

most brightly in the story of the passion. After Jesus’ arrest in the Garden of

Gethsemane, his male disciples abandoned him. Judas delivered him over to the

authorities for a bribe. Peter denied him three times. And only John, described

as “the apostle whom Jesus loved,” was present at the crucifixion.

But Mary Magdalene and the band of women who followed

Jesus and supported his ministry are described by all four gospel writers as

being present during the savior’s darkest hours. Even after Jesus took his last

breath, and all hope of redemption seemed lost, the women stayed by their

teacher and their friend and prepared his body for burial. It is precisely

because they were present, loyal even through failure, that the women who

followed Jesus were the first to witness the event that would define

Christianity: the resurrection.

Gospel accounts vary, but all four identify Mary

Magdalene as among the first witnesses of the empty tomb. According to the

synoptic Gospels, she and a group of women rose early that fateful morning,

three days after Jesus had died, to anoint the body with spices and per- fumes.

When they arrived at the tomb, they were met by divine messengers guarding the

entrance, who declared that Jesus had risen from the dead, just as he said he

would. The women immediately left the tomb behind and, “with fear and great

joy” (Matthew 28:8), ran to tell the other disciples. Luke notes that on their

way, they remembered what Jesus had taught them about resurrection, confirmation

of the fact that these women had been present for some of Christ’s most

important and intimate revelations and that they took these teachings to heart.

But when the breathless women arrived at the home

where the disciples had gathered, the men did not believe them. Women were

considered unreliable witnesses at the time (a fact that perhaps explains why

the apostle Paul omitted the women from the resurrection account entirely in

his letter to the Corinthian church), so their proclamation of the good news

was dismissed by the men as an “idle tale,” the type of silly gossip typical of

uneducated women. Perhaps the men invoked the widely held belief that, just

like their sister Eve, women were easily duped.

A few, however, were curious enough to take a look

at the tomb, and so, according to John’s account, Mary returned with peter and

another disciple to the place she had encountered the messengers. The men saw

for them-selves an empty grave and a pile of linen wrappings folded neatly

within it, and conceded to the women that the tomb was indeed empty. However,

John 20:9 notes, “they still did not understand from scripture that Jesus had

to rise from the dead.”

The men returned to report what they had seen to

the rest of the disciples, leaving Mary behind. Perhaps disciples posited the

theory that Jesus’ body had been stolen, for John wrote that Mary, once so full

of breathless excitement and impassioned belief, now stood outside the tomb,

crying.

Angels appeared and asked her what was wrong.

“They have taken my Lord away,” she told them,

fully accepting the disciple’s dismissal of her “idle tale” of

The angels were then joined by a mysterious man,

whom Mary assumed to be the gardener. He, too, asked why she was crying.

“Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where

you have put him, and I will get him,” she pleaded (v. 15).

Only when he called her by her name did she

recognize the man as Jesus.

“Mary,” he said.

“Rabboni!” she cried.

“Do not hold on to me,” Jesus urged as she fell

before his feet, “for I have not yet ascended to the Father. Go instead to my

brothers and tell them, ‘I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God

and your God’”

And so again, Mary Magdalene ran to the house where

the disciples were staying and told them she had seen the risen savior

face-to-face. “I have seen the Lord!” she declared. But it was not until Jesus

appeared to the men in person, allowing them to touch the wounds in his hands

and side, that they finally believed. Far from being easily deceived, women

were the first to make the connection between Christ’s teachings from scripture

and his resurrection, and the first to believe these teachings when they

mattered the most. For her valor in twice sharing the good news to the

skeptical male disciples, the early church honored Mary Magdalene with the

title of Apostle to the Apostles.

That Christ ushered in this new era of life and

liberation in the presence of women, and that he sent them out as the first

witnesses of the complete gospel story, is perhaps the boldest, most overt

affirmation of their equality in his kingdom that Jesus ever delivered. And yet

too many Easter services begin with a man standing before a congregation of

Christians and shouting, “he is risen!” to a chorused response of “he is risen

indeed!” Were we to honor the symbolic details of the text, that distinction

would always belong to a woman.

***

This was an excerpt from A Year of Biblical

Womanhood.

For more reflections on the women surrounding

Jesus’ passion, check out last year’s series, The Women of the Passion:

Part 1: The Woman at Bethany Anoints Jesus

“We cannot know for sure whether the woman who anointed Jesus saw her actions as a prelude to her teacher’s upcoming death and burial. I suspect she knew instinctively, the way that women know these things, that a man who dines at a leper’s house, who allows a woman to touch him with her hair, who rebukes Pharisees and befriends prostitutes, would not survive for long in the world in which she lived.”

Part 2: Mary’s Heart is Pierced (Again)

"The cross is a complicated, frightening thing. There, the God of the Universe experienced every imaginable suffering of his creation, right down to the sense of isolation and betrayal when the Divine seems far away. Because of the cross, God fellowships in our suffering, and we fellowship in his. Because of the cross, we can never say that God doesn’t understand. In this moment, when Mary’s eyes locked with the eyes of the boy she once nursed, once tickled, once watched fall asleep, I imagine that Jesus understood the suffering of mothers, perhaps the most powerful suffering of all."

"They had no idea how, without the help of men, they could ever move away that heavy stone. But as soon as the blue light of dawn seeped through the windows in the morning, the women rose and, in an act of radical friendship and faith, went to the tomb anyway..."

Part 4: Mary Magdalene – Apostle to the Apostles

“Far from being easily deceived, women were the first to make the connection between Christ’s teachings from Scripture and his resurrection, and the first to believe these teachings when they mattered the most. For her valor in twice sharing the good news to the skeptical male disciples, the early church honored Mary Magdalene with the title of Apostle to the Apostles."

Wishing you all a lovely Holy Week! (See also: "Holy Week for Doubters")

March 28, 2013

See you in Missouri / Arkansas / D.C. / Seattle

I’ve got a busy April ahead and wanted give you an early heads-up about some upcoming events:

Saturday, April 13Columbia, MO

What: SURGE 2013 (The Missouri Conference of the UMC)

About: “New York Times Bestselling author Rachel Held Evans reminds us, not all who wander are lost. Join pastors, college-age persons, and congregations as we continue to connect with young adults on a walkabout”

Where: Missouri UMC; 204 S. 9th., Columbia, MO

When: 8:30 a.m.- 4:00 p.m.

Cost: $12 (deadline to register April 1)

Registration is open to anyone who wishes to attend!

Saturday, April 20 – Sunday, April 21Ft. Smith, AR

What: First Presbyterian Church, Ft. Smith AR

When: 5 p.m. Saturday, 10 a.m. Sunday

Everyone welcome!

Friday, April 26 – Saturday, April 27Fairfax, VA

What: The BLUE Conference

About: “It doesn’t matter if you’re a stay-at-home mom or someone with so many security clearances you couldn’t tell us what you do for a living even if you wanted to. The purpose is to develop a Kingdom movement that radiates from the church into every channel of culture reflecting God’s commitment to restoration and the common good. You will have the opportunity to network within your vocational channel of culture and learn from leading cultural influencers in media, education, government, arts and entertainment, business, the social sector, and the church.”

Where: Fairfax Community Church

When: Check out the schedule

Cost: See Registration Information

Media: Follow BLUE on Twitter

Tuesday, April 30, 2012Seattle Pacific University

What: Chapel – “My Year of Biblical Womanhood” followed by Q&A

Where: Sanctuary, First Free Methodist Church

When: 9:30 a.m.

***

Let me know if I'll see you!

March 27, 2013

Holy Week for Doubters

It will bother you off and on, like a rock in your shoe,

Or it will startle you, like the first crash of thunder in a summer storm,

Or it will lodge itself beneath your skin like a splinter,

Or it will show up again—the uninvited guest whose heavy footsteps you’d recognize anywhere, appearing at your front door with a suitcase in hand at the worst. possible. time.

Or it will pull you farther out to sea like rip tide,

Or hold your head under as you drown—

Triggered by an image, a question, something the pastor said, something that doesn’t add up, the unlikelihood of it all, the too-good-to-be-trueness of it, the way the lady in the thick perfume behind you sings “Up from the grave he arose!” with more confidence in the single line of a song than you’ve managed to muster in the past two years.

And you’ll be sitting there in the dress you pulled out from the back of your closet, swallowing down the bread and wine, not believing a word of it.

Not. A. Word.

So you’ll fumble through those back pocket prayers—“help me in my unbelief!”—while everyone around you moves on to verse two, verse three, verse four without you.

You will feel their eyes on you, and you will recognize the concern behind their cheery greetings: “We haven’t seen you here in a while! So good to have you back.”

And you will know they are thinking exactly what you used to think about Easter Sunday Christians:

Nominal.

Lukewarm.

Indifferent.

But you won’t know how to explain that there is nothing nominal or lukewarm or indifferent about standing in this hurricane of questions every day and staring each one down until you’ve mustered all the bravery and fortitude and trust it takes to whisper just one of them out loud on the car ride home:

“What if we made this up because we’re afraid of death?”

And you won’t know how to explain why, in that moment when the whisper rose out of your mouth like Jesus from the grave, you felt more alive and awake and resurrected than you have in ages because at least it was out, at least it was said, at least it wasn’t buried in your chest anymore, clawing for freedom.

And, if you’re lucky, someone in the car will recognize the bravery of the act. If you’re lucky, there will be a moment of holy silence before someone wonders out loud if such a question might put a damper on Easter brunch.

But if you’re not—if the question gets answered too quickly or if the silence goes on too long—please know you are not alone.

There are other people signing words to hymns they’re not sure they believe today, other people digging out dresses from the backs of their closets today, other people ruining Easter brunch today, other people just showing up today.

And sometimes, just showing up - burial spices in hand - is all it takes to witness a miracle.

March 26, 2013

Jesus Started With the ‘Outliers’

It was one of those Twitter conversations I probably shouldn’t have gotten sucked into.

We were debating whether or not it’s helpful to use language like “act like a man,” or “true womanhood,” or “real men” in our religious dialogs, and I was arguing that the goal of the Christian life is to be conformed to the image of Christ, not idealized, culture-based gender stereotypes. He was making the case that men are “hardwired” to protect women and women are “hardwired” to be protected by men, and so the lifeboats on Titanic prove that women should not teach or lead in the church. I suggested that perhaps the lifeboats on the Titanic point to a more general sense that the stronger in a dangerous situation are morally compelled to protect the weaker in a dangerous situation, and that mothers can be awfully protective of their children after all, and that a man who (for whatever reason) might be weaker than a woman in a given situation should not feel like less of a man if she protects him. “What about a husband who is confined to a wheelchair?” I asked. “Is he ‘less of a man’ because he may be dependent in some situations on his wife’s assistance? And should we perpetuate the stereotype that ‘real men’ must be physically stronger than the women in their lives?

“Yes, but that’s an unusual circumstance,” he responded. “We can’t base our theology on the outliers.”

When he said it, something clicked in my head in a way it hadn’t before, something that seems pretty obvious when you think about it, yet is so easy to forget:

“Yes, but Jesus STARTED with the ‘outliers,’” I said. “If it doesn’t work for them, it doesn’t work.”

There is this tendency within certain sectors of Christianity to assume that if our theology “works” for relatively privileged (often for white, upper-middle-class American men), then it should work well enough for everyone else, and everyone else should conform to it.

We see this a lot in the gender debates, especially among those who suggest that the only way a family can truly honor God is with a husband who functions as the family breadwinner and a wife who functions as a stay-at-home mom to their 2.5. children, regardless of finances or practicality. This may work for some people, but it doesn’t work for the family earning minimum wage, or the couple facing infertility, or this awesome church community of immigrants that shares the responsibility of child-rearing together.

Same goes for theologies that suggest the poor are poor because of their sins, that if only the sick had more faith or gave more money they would be healed, that the tsunami or the earthquake or the flood that devastated a community was clearly the result of God’s wrath on its gay inhabitants, that we can stop rape by teaching women to cover up better, that sex before marriage makes a person ‘broken’ and ‘unwanted.’

Sure, we don’t always think about women who have been sexually abused when we preach that wives need to be super-sexy to keep the interest of their husbands, or about infertile couples when we talk about how “a woman’s highest calling is motherhood,” or about our African American brothers and sisters and our indigenous brother and sisters when we trumpet America’s great “Christian heritage.”

But maybe we should.

If the gospel isn’t good news to the so-called ‘outliers,’ then it’s not good news at all. And, in fact, if our theology doesn’t start with the ‘outliers,’ then maybe we’re doing it wrong.

Jesus started with the outliers and made no bones about it:

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me,

because he has anointed me

to proclaim good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners

and recovery of sight for the blind,

to set the oppressed free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” (from Luke 4)

In the Sermon on the Mount:

“Blessed are you who are poor,

for yours is the kingdom of God.

Blessed are you who hunger now,

for you will be satisfied.

Blessed are you who weep now,

for you will laugh.

Blessed are you when people hate you,

when they exclude you and insult you,

and reject your name as evil, because of the Son of Man.

But woe to you who are rich,

for you have already received your comfort.

Woe to you who are well fed now,

for you will go hungry.

Woe to you who laugh now,

for you will mourn and weep..." (from Luke 6)

Jesus talked theology with women. He hung out with prostitutes and tax collectors. He drew crowds made up of the sick and poor. He criticized religious leaders who try to "slam the door to the Kingdom of Heaven in people's faces."

I think also of the Ethiopian eunuch (from Acts 8), a man who was ethnically and sexually “other,” who was welcomed and baptized without question or hesitation into the early church, but who would no doubt fail all of Mark Driscoll’s rigid categories for a what makes “real man” were he a part of the American evangelical church today.

Now, the point of this rambling reflection is not to further entrench the imaginary divide between the privileged “in” and the underprivileged “out.” (It should be noted that with the center of Christianity shifting to the global South and East, and with the demographics of American Christianity changing so rapidly, white American Protestants will soon find themselves in a minority, which will make this whole conversation a lot more interesting!) The point is, we can’t go around dismissing as irrelevant those for whom our pet theologies turn the good news into bad news. We have to start with them instead.

Because at the end of the day, we’re all in this Kingdom thing together. We’re all loved by God, all in desperate need of grace, all in need of one another.

In a sense, we’re all outliers.

March 25, 2013

"Washed and Waiting," Chapter 2: Loneliness and Longing

Today we pick up our yearlong series on Sexuality and The Church with a discussion on Chapter 2 of Wesley Hill’s short book, Washed and Waiting: Reflections on Christian Faithfulness and Homosexuality. We will wrap up our discussion next week, with Chapter 3 and the book’s conclusion.

Wesley’s book is meant to both complement and contrast Justin Lee’s book, Torn: Rescuing the Gospel From the Gays-vs-Christians Debate, which served as a starting point for our discussion. Both Justin and Wesley are gay, but whereas Justin concluded that a relationship with another man could be blessed by God, Wesley has chosen celibacy. I picked these two books because I think Justin and Wesley represent the very best in civil, gracious, and loving disagreement on this issue…which for them is not a mere issue, but a deeply personal journey with deeply personal implications. I highly recommend reading these books together.

You can check out every post in our series thus far here.

***

Henri Nouwen and "The Beautiful Incision"In the interlude preceding Chapter 2, Wesley highlights the life and writings of Henri Nouwen, who, (I had never realized this before reading Wesley’s book), was a celibate gay Christian.

Wesley writes that he can relate to Nouwen, who “wrestled intensely with loneliness, persistent cravings for affection and attention, immobilizing fears of rejection, and a restless desire to find a home where he could feel safe and cared for.” (87)

Wesley discovered Nouwen during a particularly difficult time in his life. “I felt isolated, tormented, and, worse, numb to whatever love, affection, and support my friends and church family were trying to extend to me. Realizing that Nouwen had struggled with the same longings and fears I was experiencing—and that he had struggled with them all his life—I felt simultaneously that a weight was lifted off my shoulders and that I had a long road still ahead of me with no end in sight” (87).

Nouwen, who later in life confessed that he had known since he was six years old that he was attracted to members of his own sex, would, in lectures and books, “speak of the strength he gained from living in community, then drive to a friend’s house, wake him up at two in the morning, and, sobbing, ask to be held.” (p. 89, quoting Philip Yancey).

Writes Wesley: “I know well these desires and wounds because, like Nouwen, I have lived with them. I am now living with them.” He concludes:

The wound of loneliness is like the Grand Canyon, Nouwen wrote, ‘a deep incision on the surface of our existence which has become an inexhaustible source of beauty and self-understanding.’ With this statement, Nouwen gave voice to the truth of the gospel that, under God’s severe mercy, evil may be turned to good, pain and suffering may be redeemed and transformed, beauty may spring from the ashes. ‘And we know that in all things God works for the good of those who love him, who have been called according to his purpose’ (Romans 8:28). Through the incision—though not beautiful in and of itself—we may glimpse the beauty of God…Nearly two thousand years ago, Good Friday gave way to Easter Sunday, and at the end of history, when Jesus appears, death will give way to resurrection on a cosmic scale and the old creation will be freed from its bondage to decay as the new is ushered in. On that day there will be no more loneliness. The wounds will be healed. (p. 92-93)Chapter 2 – The End of Loneliness

I confess this chapter was difficult to read. Tears gathered in my eyes several times as Wesley, with remarkable candor, describes the loneliness that comes with choosing celibacy. In fact, I’m not sure I’ve read a more incisive and touching explanation for why human beings crave intimacy than this one.

“The homosexual Christian who chooses celibacy continually, to one degree or another, it seems to me, finds himself or herself longing for something relationally that remains tragically, tantalizingly just out of reach,” writes Wesley. He shares an email he wrote to a friend during a time in his life when he was feeling especially lonely:

“The love of God is better than any human love. Yes, that’s true, but that doesn’t change the fact that I feel---in the deepest parts of who I am—that I am wired for human love. I want to be married. And the longing isn’t mainly for sex (since sex with a woman seems impossible at this point); it is mainly for the day-to-day, small kind of intimacy where you wake up next to a person you’ve pledged your life to, and then you brush your teeth together, you read a book int eh same room without necessarily talking to each other, you share each other’s small joys and heartaches…One of my married friends told me she delights to wake up in the night and feel her husband’s foot just a few inches from hers in bed. It is the loss of that small kind of intimacy in my life that feels devastating. And, of course, this ‘small intimacy’ is precious because it represents the ‘bigger intimacy’ of the covenantal union between two lives.” (105)

Wesley says that he, like most people, longs for the experience of mutual desire—the feeling of knowing and loving someone, and being known and loved by that person in return, at an intimate, unconditional level.

He quotes Rowan Williams who has said, “To desire my joy is to desire the joy of the one I desire: my search for enjoyment through the…presence of another is a longing to be enjoyed…[Romantic] partners ‘admire’ in each other ‘the lineaments of gratified desire.’ We are pleased because we are pleasing.”

The question, posed by both Wesely and Rowan Williams is, how can gay and lesbian believers come to know this kind of love, this awakening of joy and delight, which is the experience of mutual desire?

Wesley runs through several options, including same-sex relationships (which he believes are a violation of God’s design), mixed orientation marriages (which he believes may work in some cases, but probably not his own), and celibacy.

Those who find themselves in the position of being single and celibate can find comfort and hope in a relationship with a God who longs for intimacy with his creation, Wesley says.

“I often wonder if coming to understand and believe that God does, indeed desire us,” he writes, “and that we are invited to return his desire might be the ‘remedy’ in some ultimate sense, for the loneliness and craving for love that I and other homosexual Christians experience on a regular basis. Leaving through the Bible, I find dozens of indications that God loves his people in precisely the way that Williams describes, and I ask myself: Could this be the end of my quest?” (p. 107)

Wesley cites passages like Hosea 11:8-9, Ezekiel 16:8, Zephaniah 3:17, , Romans 5:5, Ephesians 1:3-8, and 1 Peter 1:8, and concludes that “in some profound sense, this love of God—expressed in his yearning and blessing and experienced in our hearts—must spell the end of longing and loneliness for the homosexual Christian. If there is a ‘remedy’ for loneliness, surely this must be it. In the solitude of our celibacy, God’s desiring us, God’s wanting us, is enough. The love of God is more valuable than any human relationship…And yet we ache. The desire of God is sufficient to heal the ache, but still we pine, and wonder.” (108)

But Wesley also acknowledges the importance of community. Quoting a professor of his, he observes that “God is the one who created humans to want and need relationships, to crave human companionship, to want to be desired by other humans. God doesn’t want anyone to try to redirect their desire for community to himself…Instead, I think God wants people to experience his love through their experience of human community—specifically through the Church.” (p. 110)

Wesley notes that, historically, most commitments to celibacy are made within the context of a community—typically monastic communities. There is a need, he says, for Christians to come alongside their celibate brothers and sisters and walk with them through this loneliness, as friends and partners. And there is a need, he says, for gay Christians to open themselves up to such relationships, which can be hard when they may tend to distance themselves, in unhealthy ways, from friends of the same sex out of fear of where those friendships might become inappropriate or uncomfortable. (I had never thought about how hard that would be; Wesley does a good job offering insight and encouragement in this regard.)

“Perhaps one of the main challenges of living faithfully before God as a gay Christian is to believe, really believe, that God in Christ can make up for our sacrifice of homosexual partnership not simply with his own desire and yearning for us but with his desire and yearning mediated to us through the human faces and arms of those who are our fellow believers.” (p. 112)

Questions for Discussion1. Have you ever experienced, or are experiencing, the kind of loneliness Wesley describes in this chapter? How do you process that loneliness? What helps and what hurts?

2. This is my biggest question as we consider both Justin and Wesley’s testimonies: Do you think it is possible to fully support both Justin in his pursuit of a partnership/marriage to another man, and Wesley, in his decision based on his convictions to remain celibate? Or does the full support of one somehow diminish the support of the other? (I’d like to pose this question to Justin and Wesley, at some point. Would love to hear their perspectives on it.)

3. Obviously, hanging over the discussion this week is the Supreme Court’s upcoming decision regarding the constitutionality of Proposition 8. (Because someone is bound to ask, I’ve made it pretty clear in the past that I support gay marriage as a civil right, and would hold this position regardless of whether I believed such marriages should be blessed by my church.) I guess my question, with that in mind, is this: After reading such an intimate account of the challenges that come with a life of celibacy, is it fair for those of us who are not in the position to make such a decision ourselves to demand that others choose that life?

I’d love to know your thoughts on all of this. Please stay civil in the comment section. Unkind comments, or comments that distract us from constructive dialog, will be deleted.

Be sure to check out all the posts in our series on Sexuality and The Church.

Rachel Held Evans's Blog

- Rachel Held Evans's profile

- 1710 followers