David A. Riley's Blog, page 19

February 8, 2024

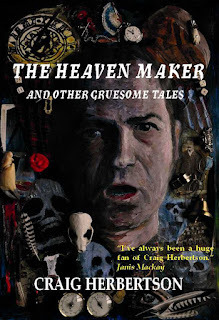

Day One of Showcasing the books published by Parallel Universe Publications: The Heaven Maker & Other Gruesome Tales by Craig Herbertson

This is day one of showcasing the books published by PUP that are still available.Day One: The Heaven Maker and Other Gruesome Tales is Edinburgh born Craig Herbertson’s first horror collection. There has been a revival of the old style horror exemplified by the gory Pan Horror collections once commonplace in newsagents and train station kiosks throughout the UK. “The Heaven Maker”, published in 1988, was one such story; at last it is once again in print along with some unseemly and dreadful companions. Also on the menu are stand alone excerpts from the critically acclaimed dark fantasy novel, “School: The Seventh Silence”, followed by an aperitif of dark songs from Herbertson’s extensive traditional repertoire. Bizarre philosophical discussions alternate with episodes of fantasy, horror… and occasional whimsy… The images and ideas come thick and fast. A very enjoyable read, perfect for lovers of fantasy that’s a bit different.

This is day one of showcasing the books published by PUP that are still available.Day One: The Heaven Maker and Other Gruesome Tales is Edinburgh born Craig Herbertson’s first horror collection. There has been a revival of the old style horror exemplified by the gory Pan Horror collections once commonplace in newsagents and train station kiosks throughout the UK. “The Heaven Maker”, published in 1988, was one such story; at last it is once again in print along with some unseemly and dreadful companions. Also on the menu are stand alone excerpts from the critically acclaimed dark fantasy novel, “School: The Seventh Silence”, followed by an aperitif of dark songs from Herbertson’s extensive traditional repertoire. Bizarre philosophical discussions alternate with episodes of fantasy, horror… and occasional whimsy… The images and ideas come thick and fast. A very enjoyable read, perfect for lovers of fantasy that’s a bit different.

Includes:

Timeless Love (originally published in Big Vault Advent Calendar 2011)

Synchronicity (originally published in Filthy Creations #2)

The Glowing Goblins (originally published in Auguries #16)

New Teacher (originally published in The Seventh Black Book of Horror)

The Janus Door

The Heaven Maker (originally published in The 29th Pan Book of Horror Stories)

The Waiting Game (originally published in Back from the Dead: The Legacy of the Pan Book of Horror Stories)

The Art of Confiscation

Gertrude

Not Waving

Spanish Suite (originally published in The Sixth Black Book of Horror)

The Anninglay Sundial

Soup (originally published in The Fourth Black Book of Horror)

A Game of Billiards (originally published in Tales from the Smoking Room)

The Navigator (originally published in Big Vault Advent Calendar 2011)

The Tasting

Steel Works

Liebniz's Last Puzzle (originally published in The Fifth Black Book of Horror)

Big Cup, Wee Cup

Gifts (originally published in Big Vault Advent Calendar 2011)

Here is a link to a detailed review of Craig's collection: Review.

Trade paperback:

amazon.co.uk £11.99

amazon.com $12.99 Barnes & Noble $12.99

ebook

amazon.co.uk £2.99

amazon.com $3.99

February 3, 2024

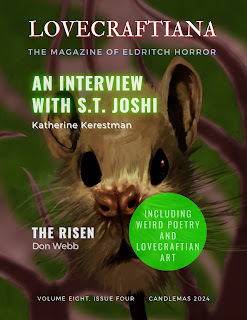

My story The Triptych of Hell is in the latest issue of Lovecraftiana

My story The Triptych of Hell is in the latest issue of Lovecraftiana, though you would be forgiven for not realising this as my name, for some reason, has been accidentally ommitted from all reference to it in the issue on amazon. Oh well, the story is still there nevertheless.

My story The Triptych of Hell is in the latest issue of Lovecraftiana, though you would be forgiven for not realising this as my name, for some reason, has been accidentally ommitted from all reference to it in the issue on amazon. Oh well, the story is still there nevertheless. January 2, 2024

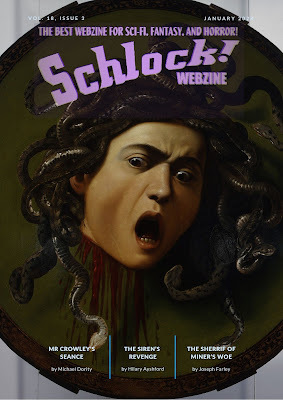

Read my story An Oddity, published in the current issue of Schlock! Webzine

My story An Oddity, which is included in the latest issue of Schlock! Webzine, can be read in full on the publisher's website: Schlock.co.uk

My story An Oddity, which is included in the latest issue of Schlock! Webzine, can be read in full on the publisher's website: Schlock.co.uk January 1, 2024

My story An Oddity is in Schlock! Webzine's January 2024 issue

Making a great start to 2024, my story An Oddity is in the current (January) issue of Schlock! Webzine. The tale is about what may or may not be a gorgon's head, hence the cover art.

Making a great start to 2024, my story An Oddity is in the current (January) issue of Schlock! Webzine. The tale is about what may or may not be a gorgon's head, hence the cover art.

HAPPY NEW YEAR

December 23, 2023

Merry Christmas

December 15, 2023

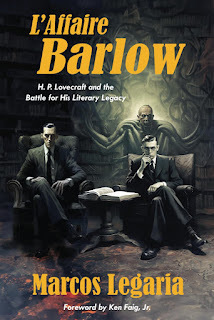

Review - L'Affaire Barlow

I expect most people are at least aware of some of the wrangles thatoccurred after the death of H. P. Lovecraft over who had control of hisliterary legacy, with August Derleth eventually emerging as the owner andcontroller of Lovecraft’s writings, in effect if not legally, despite RobertBarlow being named by Lovecraft himself as his literary executor.

I expect most people are at least aware of some of the wrangles thatoccurred after the death of H. P. Lovecraft over who had control of hisliterary legacy, with August Derleth eventually emerging as the owner andcontroller of Lovecraft’s writings, in effect if not legally, despite RobertBarlow being named by Lovecraft himself as his literary executor. Within days of Lovecraft's death a bitter feud emerged with amazinglyvitriolic accusations against the then nineteen year old Barlow by Donald andHoward Wandrei, Samuel Loveman and others, including, somewhat less openly butno less antagonistically, Derleth himself, all of whom were determined toundermine not only Barlow’s credibility in that role but his honesty andintegrity too.

L'Affaire Barlow by is a fascinating read into the shenanigans that went on in theimmediate years after the great man's death, with a myriad of scurrilousaccusations being propagated against Barlow, especially by the Wandreis,Loveman and Derleth. Indeed, the whole affair casts Derleth in a particularlypoor light, even though I have always admired him as an editor (I used to lovethe regular anthologies that were reprinted in paperback in the UK in the 1960s)and as a writer too when he wasn't trying to mimic Lovecraft. But this bookcasts a dark shadow over him, though the darkest of all is on Donald Wandreiand his brother Howard, who were particularly harsh in their condemnations ofBarlow and did not hesitate to exaggerate libelously against him. In a letterto Derleth on March 15th, 1963, a decade after Barlow's sad death by suicide,Wandrei had this to say: "Your quote about Barlow's diary serves to showwhat a ludicrous and infantile set of values and perspectives, or lack of them,typified both him and Beck - too bad Beck hasn't the sense to follow Barlow'sexample and erase himself from human existence, thereby improving the generalatmosphere for the rest of mankind."

Distastefully reprehensible though comments like this are, Derleth appearedto play a more duplicitous role in the affair, letting others fire offaccusations and even outright lies against Barlow, while pretending to beneutral to Barlow himself, even to the extent of pretending to be his friend,when he was anything but. In a letter to Wandrei on the 16th March, 1938Derleth states: “In any case, you will remember that I maintained friendlyrelations with Barlow specifically for the sake of obtaining Lovecraftmanuscripts, etc…. and this continued friendship paid off.” Years later Derlethwas not ashamed to admit what he had done. In a letter to Wandrei dated 12thMay, 1963: “Oh, I’d never suspect you ofduplicity – but me, ah, that’s another matter, in some things the endsjustifies the means, esp. when nobody’s hurt – see how I took in Barlow, didn’thurt him at all and kept him from blocking us on Lovecraft material – but Imeant to publish HPL and even if I had let Barlow blow me to do it! Luckily, Ididn’t…”

Perhaps worst of all was the rift that Donald Wandrei deliberatelycreated between Barlow and his literary hero Clark Ashton Smith, some of whosepoems he was about to publish in a small book. Lovecraftian scholar Dirk W.Mosig wrote: “I’ve long disliked Wandrei for the way in which he destroyed thefriendship between CAS and Barlow, and cooled CAS’s regard for ClaireBeck…Briefly, Wandrei wrote to Smith saying that Barlow, with Beck’s help,stole some HPL manuscripts from Mrs. Gamwell (Lovecraft’s aunt), and said in away that was vicious. He was venting a personal anger then, too. He wanted tobe the one to get the papers. Barlow, of course, was only accepting the offerof HPL’s Instructions in case of Decease, and Beck, who happened to be visitingBarlow, gave him a hand. But DW told Smith to watch out for those ghouls orthey’d next be stealing from him. Barlow never found out why CAS had turnedagainst him.”

Backed up by umpteen quotes from letters written by all the participantsthis is an important memoir of a time when Lovecraft's legacy lay in thebalance. I would not be surprised if it also excites controversy and debateover the rights and wrongs exposed in it. Some of the ploys played againstBarlow can, even now, raise the hackles and I must admit to feeling righteouslyaggrieved over the poisonous lies and allegations used by his enemies. Cancelculture is definitely not something new.

Well worth a read, but don’t expect to be unmoved.

L'Affaire Barlow is published by Bold Venture Press, 2023, 214 pages

Hardcover £25.57; paperback £13.57

November 20, 2023

Swords & Sorceries: Tales of Heroic Fantasy Volume 7 now available in paperback and kindle eBook

We are pleased to announce that our latest anthology Swords & Sorceries: Tales of Heroic Fantasy Volume 7 is now available to order as either a paperback or kindle eBook. It's our biggest volume so far at 353 pages.

The stories and authors included are:

PITILESS by Stephen FrameUNHALLOWED TOMBS by Paul BatteigerSORCERIES IN ASSABARR by Andrew Graham

SCHISM OF SPECTRES by Phil Emery

THE CROSSROADS IN THE FOREST by Gavin ChappellWISPS by Jason M WaltzDARK THE SKY, RADIANT THE ROAD by Jalyn Renae Fiske

THE BLOOD OF KHALID AL'TAHIR by Craig Comer THE DARK KNIGHT OF THE SOUL by Eric Ian SteelePROHAIRESIS by Jon ZarembaBLADES FOR A BOUNTY by Harry Elliott

The artwork, as always, is by Jim Pitts.

October 19, 2023

Great new review for Swords & Sorceries: Tales of Heroic Fantasy Volume 6 on Amazon

Thank you to Richard Fisher for this great, detailed review of Swords & Sorceries: Tales of Heroic Fantasy Volume 6 on Amazon.

Thank you to Richard Fisher for this great, detailed review of Swords & Sorceries: Tales of Heroic Fantasy Volume 6 on Amazon. "Like a freight train Parallel Universe Publications continues to come down the line filled with S&S stories from authors new and old..."

"I eagerly look forward to Volume Seven which should be out sometime later this year."

For the full review click on this link: amazon.com

October 16, 2023

The Best of Lovecraftiana

My copy of The Best of Lovecraftiana, published by Rogue Planet Press and edited by Gavin Chappell, arrived today. My story The Psychic Investigator appears in it.

My copy of The Best of Lovecraftiana, published by Rogue Planet Press and edited by Gavin Chappell, arrived today. My story The Psychic Investigator appears in it. This is available from amazon.co.uk for £7.40 in paperback or as a kindle ebook.

Below as a sample of my story are the opening paragraphs:

GregConroy sat as comfortably as he could in the sound studio at Radio Lancashire,hoping to look relaxed. It was a small room, but well equipped. GillianButterworth, who would be interviewing him, was already there. She smiledencouragingly.

“We’lldo a sound test first, then start.”

He’dbeen told the interview would last fifteen minutes and be aired tomorrow on theafternoon show. It wasn’t his first time here, of course, though that didn’tmake him feel any easier. He shuffled on his chair, wishing he had not put acardigan on beneath his jacket. Even though it was a cold September day outsidehe was already feeling hot inside the studio. Luckily, as it was radio, no one wouldsee the sweat on his face – other than Gillian.

“So,what was it, Greg, made you want to become a ghost hunter?” Gillian said assoon as recording began.

Gregshook his head, before remembering no one other than Gillian would see him dothis. “I prefer psychic investigator, Gillian,” he added quickly. “Ghosts are onlyone of many phenomena I hope to come across.” He settled on his chair, startingto feel at ease with this familiar question. “It was coming across a book bythe late Colin Wilson sparked things off. It was an account of paranormalactivity in a house in Pontefract – what was to become known as the PontefractPoltergeist. I read this book umpteen times in my teens. I was fascinated byit. It was this made me want to carry out investigations of my own.”

“Youwere involved with the TV series, Hauntings.That didn’t end well, did it? What went wrong?"

“I’ma serious investigator, Gillian.” Greg leaned forward, feeling his pulse beginto quicken as his agitation at what went on with the producers of Hauntings came back to him. “I have no timefor fake clairvoyants who make ridiculous claims about evil spirits the minutethey step inside a building, especially where nothing, not even remotely badtook place – or become possessed by hostile spirits at the drop of a hat. Theymake a mockery of everything I have tried to do. As for crew members who screamin panic at the slightest noise! It became obvious to me my reputation would bein tatters if I stayed with that show – so I quit.”

“I’ma serious investigator, Gillian.” Greg leaned forward, feeling his pulse beginto quicken as his agitation at what went on with the producers of Hauntings came back to him. “I have no timefor fake clairvoyants who make ridiculous claims about evil spirits the minutethey step inside a building, especially where nothing, not even remotely badtook place – or become possessed by hostile spirits at the drop of a hat. Theymake a mockery of everything I have tried to do. As for crew members who screamin panic at the slightest noise! It became obvious to me my reputation would bein tatters if I stayed with that show – so I quit.”“Youplace a great deal of importance on your reputation for scepticism, Greg?”

“Iapproach every investigation with what I like to call open-minded scepticism. Yes, it takes a lot to convince me that somethingis genuine. Only facts impress me. Which is as it should be if you are aserious investigator, not a showman out to impress the gullible.”

“Whatis going to be your next investigation?”

“I’vebeen invited to Edgebottom. There’s an area of the town I’ve been told shouldbe worth looking into for strange phenomena. Grudge End.”

Gillianlooked up from her notes. For a moment Greg was sure he saw concern cross herface before professionalism took over and she moved on to the next question.