Matt Ridley's Blog, page 31

September 23, 2015

Punctured pessimists

Fox News has dug up some remarkable botched

predictions about the environment. Most are familar but three were

new to me:

2. "[By] 1995, the greenhouse effect

would be desolating the heartlands of North America and Eurasia

with horrific drought, causing crop failures and food riots…[By

1996] The Platte River of Nebraska would be dry, while a

continent-wide black blizzard of prairie topsoil will stop traffic

on interstates, strip paint from houses and shut down

computers." Michael Oppenheimer, published in "Dead Heat," St. Martin's Press,

1990.

Woops

4. "Using computer models, researchers

concluded that global warming would raise average annual

temperatures nationwide two degrees by 2010."

Associated Press, May 15, 1989.

Woops

7. "By the year 2000 the United Kingdom

will be simply a small group of impoverished islands, inhabited by

some 70 million hungry people ... If I were a gambler, I would take

even money that England will not exist in the year

2000."Paul Ehrlich, Speech at British Institute For Biology,

September 1971.

Amazingly, Ehrlich defends his prediction.

"When you predict the future, you get things

wrong," Ehrlich admitted, but "how wrong is another question. I

would have lost if I had had taken the bet. However, if you look

closely at England, what can I tell you? They're having all kinds

of problems, just like everybody else."

Here is a sample of our ``all sorts of problems' in Britain,

compared with 1971:

GDP per capita has roughly doubled in real terms

child mortality is down by three-quarters

lifespan is up by eight years

obesity is a bigger problem than hunger

four times as many people go to university

people take seven times as many foreign holidays

twice as many people have a car

otters and ospreys are far more numerous

air pollution is much decreased

beaches and rivers are cleaner

the internet exists

New cousins

The big news of the day, indeed of the year, is that we

The big news of the day, indeed of the year, is that we

now know, almost for sure, that central Asian hominins 50,000 years

ago were not Neanderthals, but a different species, the Denisovans,

as distantly related to Neanderthals as they were to us. A genome

extracted from a little finger found in the Denisova cave (above)

in the Altai mountains of south-western Siberia seems to say so as does a morphologically

distinct tooth.

But that is not the biggets surprise. Astonishingly, Melanesian

people from Papua New Guinea have a 5% ancestral contribution from

these Denisovans to their genomes. The implication: as Africans

spread around the Indian ocean 50,000 years ago, they did some

cross-breeding with Asian native hominins, who were of this

hitherto unknown species that lived in Siberia (and presumably

further south as well).

Holy Mackerel, what an incredible historical tool DNA sequencing

is! Truly there is scripture in it.

I don't have time to explore this remarkable story and its

implications today, because of holidays and snow, but I

recommend John Hawks's analysis, of which this is an

extract:

Well, it's obviously very exciting, but I

find it very difficult to talk about these Pleistocene populations

without falling into bad habits.

Our common ancestry as humans goes back to

the Early and Middle Pleistocene. The (now multiple) Neandertal

genomes and the Denisova genome share genes with some people and

not others because of this common ancestry.

In addition, some living people

carry even more genes from Neandertals because they

have an appreciable fraction of Neandertal ancestry. That makes it

nonsensical to talk about "Neandertals and the ancestors of modern

humans". Neandertals are among the ancestors

of modern humans.

Just so with Denisova. It's nonsensical to

talk about a three-way split between Neandertals, Denisova and

modern humans. We can talk about a population model with a clade

separating an ancestral Neandertal-Denisova population from

contemporary Africans.

I have to remind myself again and again when

I talk to people about these issues that "modern human ancestors"

is not a group that excludes these Pleistocene people.

Were they capable of exchange?

How new words and new genes are coined

My latest Mind and Matter column in the Wall

Street Journal, with added links:

Don't look for the soul in the language of DNA

Back in the genomic bronze age-the 1990s-scientists used to

think that there would prove to be lots of unique human genes found

in no other animal. They assumed that different species would have

many different genes. One of the big shocks of sequencing genomes

was not just the humiliating news that human beings have the same

number of genes as a mouse, but that we have the same genes, give

or take a handful.

This humiliation deepened recently when David Knowles and Aoife McLysaght at Trinity

College, Dublin, tracked down, at last, some uniquely human genes:

just three of them. They estimate that there are, altogether,

probably no more than 18 of this wholly unique kind-out of 22,568

genes in total. Over the span of our history, human beings seem to

have acquired a brand-new gene only every third of a million

years.

The three that Drs. Knowles and McLysaght identified lie in

stretches of DNA that are gobbledegook in chimpanzees, gorillas,

gibbons and macaques, so the chances are they have sprung to life

as protein-coding sequences in human beings uniquely. (A gene is

the digital recipe for making a protein molecule.)

The functions of these three genes are not yet known (since they

don't exist in mice, experiments are tricky), though one seems to

be slightly more active in people with a form of leukemia. They are

small and simple genes, however-unlikely candidates to hold the

recipe for the human soul.

This might seem to leave a small hook upon which philosophers

could hang the uniqueness of the human race. But we have long known

that our uniqueness lies in the order and combination of our genes,

not in the ingredients themselves. DNA is not only like a language;

it is a language, a linear sequence of recombinable

digital characters of infinite variety.

There are close parallels between DNA and a language like

English. Just as evolution uses the same 22,000 genes in a

different order to make a rhinoceros or a rabbit, so Shakespeare

used many of the same 18,000 words in each of his plays. The 10

most common words in "Othello" and "King Lear" are the same (I,

and, the, to, you, of, my, that, a, in), yet the plays are very

different. The English language, like the human genome, contains

very few brand new words that were invented recently from

scratch.

Most new English words arise by different means: by borrowing

from foreign languages (Schadenfreude, pajama); by recombining

existing words (blogosphere, download); or by the addition of

second meanings to existing words (green, mouse).

All of these habits are common in the genome, too. Lateral gene

transfer brings genes from one species into another, especially

among bacteria (less often among mammals like us). This is just

like borrowing a foreign word. Genes recombine by fusing in whole

or in part, by a process known as exon shuffling (exons are the

separate stretches of code that are used to make one protein in

split genes). This is just like recombining existing words. And

genes often duplicate themselves and then diverge into different

functions, just as old words acquire new meanings.

About 800 million years ago, a gene for a simple pigment protein enabling

worm-like creatures to see was duplicated, and the daughter genes

diverged to give the different proteins used in the rods and cones

of the eye. About 500 million years ago, in a lamprey-like fish,

the gene used in cones duplicated and diverged again to give us

blue versus yellow color vision. About 30 million years ago, in a

tree-climbing primate, the yellow gene duplicated and diverged

again to give us green-red color vision.

Genes also die out, just as words do. When they are still

recognizable but no longer in use, they are called pseudogenes. The

word "theatrophone" is a forgotten linguistic pseudogene, and the

word "minidisc" is becoming one. The words "trebuchet" and

"cenotaph" are examples of extinct words that sprang back to

life-something that pseudogenes sometimes do as well.

Cancer, chemicals, Carson and smoking

Rachel Carson, in her hugely influential book Silent Spring, wrote that she expected an

epidemic of cancer caused by chemicals in the environment,

especially DDT, indeed she thought it had already begun in the

early 1960s:

``No longer are exposures to dangerous

chemicals occupational alone; they have entered the environment of

everyone-even of children as yet unborn. It is hardly surprising,

therefore, that we are now aware of an alarming increase in

malignant disease.

The increase itself is no mere matter

of subjective impressions. The monthly report of the Office of

Vital Statistics for July 1959 states that malignant growths,

including those of the lymphatic and blood-forming tissues,

accounted for 15 per cent of the deaths in 1958 compared with only

4 per cent in 1900. Judging by the present incidence of the

disease, the American Cancer Society estimates that 45,000,000

Americans now living will eventually develop cancer. This means

that malignant disease will strike two out of three families. The

situation with respect to children is even more deeply disturbing.

A quarter century ago, cancer in children was considered a medical

rarity. Today, more American school children die of cancer than

from any other disease. So serious has this situation become that

Boston has established the first hospital in the United States

devoted exclusively to the treatment of children with cancer.

Twelve per cent of all deaths in children between the ages of one

and fourteen are caused by cancer. Large numbers of malignant

tumors are discovered clinically in children under the age of five,

but it is an even grimmer fact that significant numbers of such

growths are present at or before birth. Dr. W. C. Hueper of the

National Cancer Institute, a foremost authority on environmental

cancer, has suggested that congenital cancers and cancers in

infants may be related to the action of cancer-producing agents to

which the mother has been exposed during pregnancy and which

penetrate the placenta to act on the rapidly developing fetal

tissues.''

Carson was wrong about this. Not only has DDT proved not to be a

carcinogen, but the cancer epidemic caused by exposure of the

general public to chemicals has wholly failed to materialise. Study

after study has found that there is no increase in cancer incidence

or death in the general population, when corrected for age, to be

explained by man-made chemicals. Those, like Paul Ehrlich, who

confidently predicted that the lifespan of Americans would fall to

42 years by the end of the twentieth century thanks to such cancer

epidemics, were proved badly wrong.

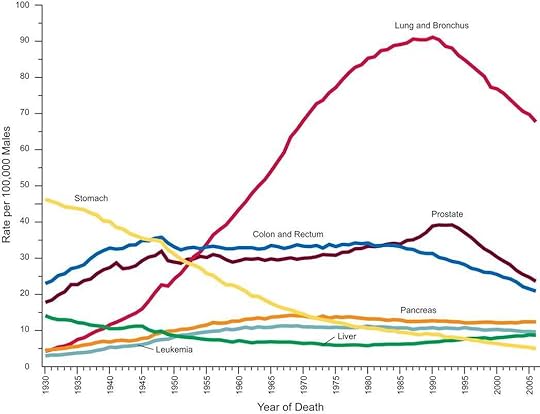

Here are the charts of cancer deaths for men and women, adjusted

for age, in the United States since the 1930s.

The one that stands out, of course, is lung cancer. The rapid

increase in lung cancer (boosted surely changing diagnosis in the

early years) was caused by the increase in smoking, of course.

Almost nobody now challenges that. But they did once. Indeed, one

of the most vociferous opponents of the theory that smoking causes

lung cancer was none other than Carson's mentor, William

Hueper.

So obsessed was Hueper with his notion that pesticides and other

synthetic chemicals were causing an epidemic of cancer and that

industry was covering this up, that he bitterly opposed the

suggestion that smoking take any blame - as an industry plot.

Here he is writing a paper called Lung Cancers and their Causes

in 1955 in CA, a cancer journal for clinicians

http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/content/abstract/5/3/95:

1. The total epidemiological, clinical,

pathological, and experimentalevidence on hand clearly indicates

that not a single but severalif not numerous industrial or

industry-related atmospheric pollutantsare to a great part

responsible for the causation of lung cancer.

2.While the available data do not permit any

definite statementas to the relative importance of the various

recognized respiratorycarcinogens in the production of lung cancers

in the generalpopulation, they nevertheless unmistakingly suggest

that cigarettesmoking is not a major factor in the causation of

lung cancernor had it a predominant role in the remarkable increase

ofthese tumors during recent decades.

3. In view of the fact thatnot only a great

deal of the existing circumstantial epidemiologicalevidence but

also pratically the entire factual and conclusiveevidence available

on exogenous respiratory carcinogens areeither of occupational

origin or point to industry-related factors,it would be most unwise

at this time to base future preventivemeasures of lung-cancer

hazards mainly on the cigarette theoryand to concentrate the

immediate epidemiological and experimentalefforts on this evidently

overpropagandized and insufficientlydocumented concept.

When environmentalists want to attack a sceptic these days, they

quite frequently accuse him or her of being the kind of person who

would have defended the tobacco lobby - in some cases with

justification. So it is ironic to find that possibly the most

iconic and original text of the entire environmental movement,

Silent Spring, was built on the work of a fervent tobacco defender.

Hueper is quoted frequently throughout Carson's book.

By the way, in my book I say that Rachel Carson `expected DDT

"to cause practically 100 per cent of the human population to be

wiped out from a cancer epidemic in one generation"'. This is

inaccurate: I slipped up. I relied on an article in a magazine called Front Page in

July 2003 for this quotation, and unusually I did not check it with

Carson's original text. Alerted by a reader, Ed Darrell (thanks!) I

have now checked Carson's Silent Spring, and while Carson strongly

implies that she does indeed expect a major mortality from cancer

caused by DDT, what she actually wrote is the following:

In the springof 1961 an

epidemic of liver cancer appeared among rainbow trout

in many federal, state, and private hatcheries. Trout in both

eastern and western parts of the United States were affected; in

some areas practically 100 per cent of the trout over three years

of age developed cancer. ...The story of

the trout is important for many reasons, but chiefly

as an example of what can happen when a potent carcinogen is

introduced into the environment of any species. Dr. Hueper has

described this epidemic as a serious warning that greatly increased

attention must be given to controlling the number and variety of

environmental carcinogens. 'If such preventive measures are not

taken,' says Dr. Hueper, 'the stage will be set at a progressive

rate for the future occurrence of a similar disaster to the human

population.'

My book criticises Carson and her followers for their

exaggerated pessimism which led to the phasing out of DDT as an

anti-mosquito weapon and hence led directly to the resurgence of

malaria. This is a story that has been well told in many places and

deserves to be better known. But I find many of DDT's defenders

then go on to make a claim that I do not believe is correct, namely

that DDT had no impact on birds, and that the story that it led to

the thinning of eggshells in birds at the end of long food chains,

such as falcons and pelicans (and also damaged the reproduction of

predatory mammals such as otters), is false. I simply do not accept

that. The evidence of bioaccumulation in fat, of eggshell thinning

and of DDT's role in the decline of raptors and other predatory

birds in the 1960s seems to me fairly strong, though not overhwelming. The

ending of indiscriminate and widespread spraying of DDT is probably

a good thing.

It is, fortunately, very easy to use DDT against malarial

mosquitoes without poisoning birds. The solution is to use it

sparingly on the inside walls of houses, where anopheline

mosquitoes rest during the day. This targets the pest while not

allowing the pesticide to contaminate the food chain in nearby

ecosystems. The best of both worlds.

September 13, 2015

Genetics is good for you

My Times column is on the risks of genetic

research and therapy:

Fifteen years after the first sequencing of the

human genome, the genetic engineering of human beings is getting

closer. Will that mean designer babies and the rich winning life’s

lotteries from the start? And will we ever stop this slither down

the slippery slope to playing God? My answers are: no, and I hope

not. Despite dire predictions, almost nothing but good has come

from genetic technology so far, and we’ve proved that we don’t slip

down such slopes: we tread carefully.

The current excitement is over gene editing. A precise way of

doing this, called CRISPR-cas9, is all the rage among the

white-coated pipette-users. Last week, Britain’s five leading

medical research bodies (one of which, I should declare, counts me

as a fellow, the Academy of Medical Sciences) issued a joint

statement supporting the careful use of the new technique on human

cells for research and possibly therapy. They even recognised that

there might one day be a justifiable demand to use the new

technique on embryos in such a way that the changes would be

inherited.

We have had bio-ethical worries about six times in the past four

decades. First, in the mid-1970s, the discovery of how to do

genetic engineering in bacteria led to agonised debates about the

risks of biological warfare and accidents. Scientists themselves

imposed a moratorium and held a conference to devise rules. Today

the technique is routinely used, has virtually never been misused,

and has saved or improved the lives of millions: diabetics, for

example, use human insulin made by bacteria genetically engineered

to include human genes. It turned out better than feared.

Second, in the late-1970s, the discovery of how to fertilise

human eggs in test tubes led to equally agonised debates about what

this might do to human reproduction — such as allowing people to

seek out highly prized human specimens to father or mother their

children. In fact, the technology is used not to help people have

other people’s babies, but to help them have their own. It has

largely cured a wretched disease — infertility — and made millions

happy. It turned out better than feared.

Third, in the 1990s scientists began to modify the genes of

plants. Opponents raised the prospect of horrifying risks to our

food and the environment. Yet trillions of genetically modified

meals have now been eaten by animals and people with zero health

problems. GM crops have cut insecticide use, raised yields and

delivered healthier foods. Today’s scandal is not the harm GM crops

have done, but the suffering they have not been permitted to

alleviate, thanks to irrational opposition. Even if you are still

worried, you must concede that so far it has turned out better than

feared.

Fourth, around the millennium, scientists developed techniques

to clone mammals and some of us found ourselves on talk shows

discussing when vain plutocrats would duplicate themselves or their

pets, and at what risk to morality. In fact, cloning has proved

helpful in only a very few laboratory settings, but aside from one

or two pretty harmless pet-cloning episodes, has not been used at

all for frivolous purposes. It turned out better than feared.

Fifth, scientists sequenced the human genome, identified

disease-causing mutations and began to offer pre-implantation

genetic diagnosis to avoid bringing people into the world with

conditions such as cystic fibrosis or Huntington’s disease. Critics

worried that people would use the technique to make designer babies

who were good at the piano or maths. Yet demand for such positive

selection has proved minimal, partly because identifying specific

genes for specific traits is hard — and misreads the way genomes

work — and partly because, again, it turns out that people want

children like themselves, not paragons. Besides, good education is

still a far better way of giving a child an advantage. It turned

out better than feared.

Sixth, scientists discovered how to use viruses to insert new

genes into living tissues to cure certain fatal diseases —

so-called gene therapy. Early trials in human beings using

retroviruses triggered cancer and were abandoned. But safer

lentivirus gene therapy has now proved capable of saving lives, such

as those of immune-deficient babies, and is being used in more than

700 different trials. It turned out better than feared.

The score so far is six-nil to the optimists, then. Diabetics,

IVF children, bees in GM crops, parents who carry cystic fibrosis

or Huntington’s disease, babies with severe combined immune

deficiency — all have benefited. It has been feasible to use

genetic techniques for biological warfare and designer babies for

decades now; and it has not happened.

As the reaction to early gene therapy failures illustrate, the

slopes are not slippery. We advance very carefully down them,

retreating if necessary and re-evaluating the issues at every

stage. People want to use these techniques to cure diseases, not to

do eugenics. Genetic knowledge has not undermined morality or

respect for human life. All this does not, of course, prove that

future techniques will not be abused, but it must count for

something.

The latest gene-editing technique is generating attention

because it is so much more precise and effective than previous ways

of altering genes. Its first use will probably be in gene therapy —

extracting T cells from a cancer patient, editing the cells’ genes

to fight the cancer and re-injecting them — but even this is a long

way off. Work on germ-line genes is even further away. Some

scientists are calling for a moratorium on even the experimental

use of CRISPR-cas9 on embryos until we have discussed all the

ethical implications.

That would be a mistake. As genetically modified plants have

shown, moratoriums are blunt instruments — easy to impose and

difficult to lift when it turns out they are doing more harm than

good, especially in the age of social media.

Experiments produce knowledge to inform debates. A good example

is the recent debate on mitochondrial donation, a technique

developed in the laboratory before being licensed for use in

patients, where it may soon prevent dreadful degenerative diseases.

When the ethical debate on its use happened, seven years’ worth of

experimental results were on hand to answer many of the questions

raised. A moratorium would have meant debating in ignorance.

We should always tread carefully, but we should take comfort

from the truly remarkable track record of genetic technologies in

alleviating more human suffering than we dared to hope, and

encouraging fewer bad outcomes than we feared.

September 6, 2015

Demography does not explain the migration crisis

My Times column on African demography and the

migration crisis:

Even the most compassionate of European liberals

must wonder at times whether this year’s migration crisis is just

the beginning of a 21st- century surge of poor people that will

overwhelm the rich countries of our continent. With African

populations growing fastest, are we glimpsing a future in which the

scenes we saw on the Macedonian border, or on Kos or in the seas

around Sicily last week will seem tame?

I don’t think so. The current migration crisis is being driven

by war and oppression, not demography. Almost two thirds of the

migrants reaching Europe by boat this year are from three small countries: Syria,

Afghanistan and Eritrea. These are not even densely populated

countries: their combined populations come to less than England’s,

let alone Britain’s, and none of them is in the top 20 for

population growth rates.

Well then, perhaps that is even more ominous. If these three

relatively small countries can cause such turmoil, imagine what

would happen if say the more populous countries in Africa fell into

similar chaos. Today Africa’s population (north and sub-Saharan) is about 50 per cent larger than Europe’s (East

and West). By 2050, when — according to United Nations estimates —

Africa’s population will have more than doubled from 1.1 billion to

about 2.4 billion people and Europe’s will have shrunk from 740

million to about 709 million, there will be more than three

Africans for every European.

Actually, demography is a poor predictor of migration. Nowhere

in the world are people leaving countries specifically because of

population growth or density. The population density of Germany is five times as high as that of Afghanistan

or Eritrea: unlike water, people often move up population

gradients. Tiny Eritrea, with only five million people, is a hell-hole for purely political reasons.

It has a totalitarian government that tries to make North Korea and

the old East Germany look tame: it conscripts every 17-year-old

into lifelong and total service of the state. No wonder 3 per cent

of its people have already left.

It is equally obvious why people are clamouring to leave Syria

and Afghanistan: violence is driving them out, not shortage of

food, space, or water, let alone climate change or anything else.

(Notoriously, in 2005 the UN Environment Programme forecast 50 million climate-change refugees by

2010.)

So it is simply not the case that migration of Africans (or

Asians) will be driven by their ever-increasing numbers. Ethiopia,

next-door to Eritrea, is the second most populous country in

Africa, with higher population density than Eritrea, and 90 million

people. But its government is only mildly authoritarian, its

economic growth rate is an astonishing 8-12 per cent over the past

five years and people are not clamouring to leave.

Geographically speaking, Africa is an enormous continent. You can fit China, India, the United States,

Mexico, Europe and Japan inside it, and still have space left over.

When it has a population of 2.4 billion in 2050, it will still have

fewer people than the 4 billion who live in those places today. Of

the 50 least densely populated countries in the world, 16 are in Africa. The continent is far from

overflowing.

As for feeding this multitude, much of Africa can grow fabulous

crops several times a year. Without access to synthetic fertilizer,

yields have lagged behind Asia, but they are starting to catch up

and when they do, Africa will easily be able to feed 2.4 billion

people and export a surplus. Already, despite fast-growing

populations, famine is gone from Africa, except where mad and bad

regimes cause it.

With the death tolls from HIV-Aids and malaria falling rapidly,

the continent is currently experiencing a plunge in child

mortality, which in turn is encouraging birth rates to fall: when

people expect their children to live, they have fewer of them. The

birth rate in Kenya has halved in the past 40 years. It is called

the demographic transition, and it happened here more than a

century ago.

Africa’s population growth will slow during this century. The

richer it gets the more that growth rate will slow. But there are

already easily enough Africans to overwhelm Europe’s capacity to

cope if they all come here, so there is nothing especially alarming

about the idea of a larger future population in Africa. The problem

isn’t demography.

No, what drives migration is violence, perpetrated these days

either by dictatorial regimes, or by religious extremists, rarely

by other causes.

In Syria, of course, both causes have combined to deadly effect.

The global Sunni-Shia civil war, the war of militant Islamists

against Christians, the kidnapping of women and children by Boko

Haram, Islamic State and the Lord’s Resistance Army — these are the

kind of things that will drive poor people into Europe from Africa

and Asia. The best way to make that flow less overwhelming is not

to reduce population but to extinguish wars, expel dictators and

calm religious extremisms: easier said than done.

The one demographic trend that gives cause for concern is the

birth rate among religious extremists. As Eric Kaufmann pointed out

in 2010 in his book Shall the Religious Inherit the

Earth?, there is a dramatic and growing difference between

the family size of moderate and fundamentalist believers in every

major religion. Fundamentalists are literally out-breeding

moderates within Islam, Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Mormonism

and Judaism. Ultra-Orthodox Israeli Jews have an average of 7.5 children; secular ones

2.2. In cities in Muslim countries, women who are most in favour of

Sharia have twice as many children as women who most oppose it.

Combine this with the result derived from twin studies that,

while the particular religion you practise clearly does not run in

the genes, the degree of religious enthusiasm does to some extent.

Imagine then that by the middle of this century, people with a

tendency to become highly religious have become a much greater

proportion of the population than today. That could be a recipe for

more violence. (You may think I am equating all religion with

violence. No, but next time you hear about a violent atrocity on a

train or in a shopping mall, you don’t say to yourself — there go

those agnostics again.)

Fortunately, children often do the opposite of what their

parents tell them, and religious revivals have a tendency to fade.

So it is just as likely that the spasms of violence causing surges

of migration from poor countries will have died away by mid

century.

August 25, 2015

Charities in need of reform

My Times column on charities:

David Cameron, luxuriating in the prospect of weak

opposition, has a chance to think about radical reform of both the

private and public sectors. But there is a third sector that

requires his attention even more urgently. He is well known to want

to harness the generosity of Britain. To do that effectively the

charity sector needs some big thinking — because after decades of

regulatory neglect it is starting to unravel and is in crisis.

The collapse of Kids Company and the British Association for

Adoption and Fostering should ring alarm bells throughout the

sector: fear of failure or takeover is one of the things that keep

private companies effective and, for too long, charities have not

felt that breath on their neck. They have been given the benefit of

the doubt because of their noble intent.

Many charities are wonderful institutions, doing tireless work

for little reward. But too many are low on compassion and have thin

financial reserves and big pension fund deficits, making them

vulnerable to donors going on strike following revelations of

problems.

Some charities are running on fumes. Others have governance

arrangements that would never pass muster in private firms: Alan

Yentob has chaired Kids Company for 18 years. A few are little more

than arms of government delivering public services, or have become

overtly political, or covers for extremism.

A charities bill going through parliament offers the chance to

begin to tackle reform. The prime minister has asked Sir Stuart

Etherington to look into the existing system of self-regulation

under the Fundraising Standards Board. Here’s a shocking fact for

Sir Stuart to chew upon: the FRSB’s last annual report speaks of 20 billion fundraising requests

being made in the space of a year. Yet, its board found the time to

look at just one complaint — which it rejected. A body that

receives 98 per cent of its funds from the charities that it

regulates could never have been expected to bite the hand.

After years of factory trawling for funds, the big charities are

finding it ever more costly to find fish, as recent “chugging”

scandals and the plight of the poppy seller Olive Cooke have shown.

In the space of a few years, the cost to a charity of getting one

of the chugging agencies to persuade a passer-by to sign up to a

direct debit has gone up from £40 to £120, which means that even

less of a donor’s money goes to the good cause. (This leads to a

vicious circle of even less trust in charities because so little

gets through to those we wish to help.)

Here’s another issue. A parliamentary question by Lord

Marlesford recently revealed that the RSPCA has access to the

police national computer, via the National Police Chiefs’ Council

criminal records office; and that its Scottish cousin, the Scottish

Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, has — even more

surprisingly — direct access to the computer. These are both

organisations with no accountability to the electorate and, with

fundraising benefits from the PR opportunities presented by arrests

and prosecutions, this is a recipe for malpractice.

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds runs some fine

nature reserves and conservation initiatives. But why on earth is

it campaigning against fracking — which it knows

offers far less threat to birds than wind farms do? It must be

because getting mentioned in the news keeps donations flowing.

Heather Hancock’s independent review for the BBC last year on

its impartiality with respect to rural issues found an

over-reliance of BBC newsrooms on the RSPB for virtually all rural

issues, not just bird-related ones: “Time after time, when asked

who their top contacts would be for a rural story, BBC programme

makers or journalists quoted the RSPB first.”

Many charities have suffered egregious activist entryism, to the

point where their leaders have views wildly at variance with those

of their donors. William Shawcross, chairman of the Charity

Commission, worries that old ladies who give money to the

RSPCA thinking it will help to save stray cats don’t expect its

executives to compare farming to the Holocaust or call for the end

of pet ownership.

In the case of Islamist extremism, the problem is less one of

innocent donors duped into supporting extremism than one in which

both donors and executives may sometimes be keen to disguise

extremism inside moderate charities. Such abuse of charitable status clearly does

happen.

Some charities have become little more than fundraising

businesses, who spend the funds they raise on fundraising. Take

Greenpeace, for example. It aims to save the world, but its output

consists largely of stunts, such as the shockingly ill-advised trespass on the ancient Nazca lines in Peru

last year, whose purpose was to get publicity . . . and raise

funds. The RSPB at least spends money on nature reserves and runs

conservation projects, but even it has been upbraided recently by

the Advertising Standards Authority for misleading advertising on

how much money was going into conservation, rather than

marketing.

Some charities have become overt political campaigners. Last

December, the Charity Commission reprimanded Oxfam for a poster attacking the

government’s austerity policies. The Indian government has been

cracking down on Greenpeace, saying that in “selectively targeting those

projects that were of great national importance for industrial

growth and development” it may have crossed the line “between

creating environmental awareness and creating social unrest”.

Many charities now depend heavily on government for their funds,

and yet are immune to freedom-of-information requests. Worse, they

spend some of those funds on lobbying government for policies

favoured by the very civil servants who doled out the cash to

them.

This is a partial list of the things that seem to be wrong in

the charity sector. I repeat that most charities do brilliant work,

including, I hope, the ones that I support. But it is a sector of

the economy ripe for the sort of radical cleansing and scrutiny

that the private and public sectors have at least begun to

endure.

A government U-turn on e-cigarettes

My Times Thunderer article on vaping:

The government now says vaping with e-cigarettes

is such a good thing that we should be prescribing it and smokers

should be rushing to take it up. It’s 95 per cent less harmful than

smoking, it’s helping people to quit tobacco and there’s no

evidence it’s a gateway into smoking: rather the reverse.

Doing a U-turn when you’ve spent two years building brick walls

on the other carriageway is challenging. The obstacles that the

government will face in encouraging vaping are more than a little

of its own making. The Public Health England review that changed

the government’s mind is concerned “that increasing numbers of

people think e-cigarettes are equally or more harmful than

smoking”.

I wonder why people think that. Could it have anything to do

with the fact that in the government’s last major announcement on

e-cigarettes in June 2013 it recommended (through the Medicines

& Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, or MHRA) “that people

do not use them”? Or that last year the chief medical officer

told New Scientist that e-cigarettes were one of

the UK’s three great health threats?

Or that in September 2013, the health secretary, Jeremy Hunt,

was lobbying MEPs to create heavy regulations on e-cigarettes by

insisting that all should be regulated as medicines? This resulted

in an effective ban on strong e-cigarettes and on consumer

advertising — which will come into force next year.

The truth is, the evidence that vaping is a game-changer in the

fight against tobacco has been obvious for years, but a combination

of yuk-factor gut instinct, drug-company lobbying and dislike of

private sector innovation led the public health mandarins to build

obstacles to it.

The new report is full of delicious coded admissions that this

was a big mistake: “The absence of non-tobacco industry products

going through the MHRA licensing process suggests that the process

is inadvertently favouring larger manufacturers, including the

tobacco industry, which is likely to inhibit innovation in the

prescription market.” Yup, some of us made that point a while

ago.

The Department of Health should have done a proper impact

assessment at the start. The extraordinary result is that Mr Hunt

will now have to navigate the onerous regulations of vaping that he

was the driving force in imposing across Europe. Still, he deserves

congratulations for having the courage to do a U-turn.

August 16, 2015

The Green Scare Problem

My Wall Street Journal column on how green scares

have led to counterproductive actions:

‘We’ve heard these same stale arguments before,” said President

Obama in his speech on climate change

last week, referring to those who worry that the Environmental

Protection Agency’s carbon-reduction plan may do more harm than

good. The trouble is, we’ve heard his stale argument before, too:

that we’re doomed if we don’t do what the environmental pressure

groups tell us, and saved if we do. And it has frequently turned

out to be really bad advice.

Making dire predictions is what environmental groups do for a

living, and it’s a competitive market, so they exaggerate.

Virtually every environmental threat of the past few decades has

been greatly exaggerated at some point. Pesticides were not causing

a cancer epidemic, as Rachel Carson claimed in her

1962 book “Silent Spring”; acid rain was not devastating German forests, as the Green

Party in that country said in the 1980s; the ozone hole was not

making rabbits and salmon blind, as Al Gore warned in the 1990s.

Yet taking precautionary action against pesticides, acid rain and

ozone thinning proved manageable, so maybe not much harm was

done.

Climate change is different. President Obama’s plan to cut U.S.

carbon-dioxide emissions from electricity plants by 32% (from 2005

levels) by 2030 would cut global emissions by about 2%. By that

time, according to Energy Information Administration data analyzed

by Heritage Foundation statistician Kevin Dayaratna, the

carbon plan could cost the U.S. up to $1 trillion in lost GDP. The

measures needed to decarbonize world energy are going to be vastly

more expensive. So we had better be sure that we are not

exaggerating the problem.

But it isn’t just that environmental threats have a habit of

turning out less bad than feared; it’s that the remedies sometimes

prove worse than the disease.

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are a case in point. After

20 years and billions of meals, there is still no evidence that they harm

human health, and ample evidence of their environmental and

humanitarian benefits. Vitamin-enhanced GM “golden rice” has been

ready to save lives for years, but opposed at every step by

Greenpeace. Bangladeshi eggplant growers spray their

crops with insecticides up to 140 times in a season, risking their

own health, because the insect-resistant GMO version of the plant

is fiercely opposed by environmentalists. Opposition to GMOs has

certainly cost lives.

Besides, what did GMOs replace? Before transgenic crop

improvement was invented, the main way to breed new varieties was

“mutation breeding”: to scramble a plant’s DNA randomly, using

gamma rays or chemical mutagens, in the hope that some of the

monsters thus produced would have better yields or novel

characteristics. Golden Promise barley, for

example, a favorite of organic brewers, was produced this way. This

method still faces no special regulation, whereas precise transfer

of single well known genes, which could not possibly be less safe,

does.

Environmentalists are currently opposing neonicotinoid

pesticides on the grounds that they may hurt bee populations, even

though the European Union notes that honeybee numbers have been

rising in the 20 years since they were introduced. The effect in

Europe has been to cause farmers to return to much more harmful

pyrethroid insecticides, which are sprayed on crops instead of used

as seed dressing, hitting innocent bystander insects. And if

Europeans had been allowed to grow GMOs, then less pesticide would

be necessary. Again, green precaution increases risks.

Nuclear power has been energetically opposed by the

environmental lobby for decades, on the grounds of danger. Yet

nuclear power causes fewer deaths per unit of energy generated than

even wind and solar power. Compared with fossil fuels, nuclear

power has prevented 1.84 million more deaths than it caused,

according to a study by two NASA

researchers. Opposition to nuclear

power has cost lives.

Likewise widespread opposition to fracking for shale gas, is

based almost entirely on myths and lies, as Reason

magazine’s science correspondent, Ronald Bailey, has

reported. This opposition has substantially delayed the growth of

onshore gas production in Europe and in parts of the U.S. That has

meant more reliance on offshore gas, Russian gas, and coal—all of

which have greater safety issues and environmental risks.

Opposition to fracking has hurt the environment.

In short, the environmental movement has repeatedly denied

people access to safer technologies and forced them to rely on

dirtier, riskier or more harmful ones. It is adept at exploiting

people’s suspicion of anything new.

Many exaggerated early claims about the dangers of climate

change have now been debunked. The Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change has explicitly abandoned previous claims that

malaria will likely get worse, that the Gulf Stream will stop

flowing, the Greenland or West Antarctic Ice sheet will

disintegrate, a sudden methane release from the Arctic is likely,

the monsoon will collapse or long-term droughts will become more

likely.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the ledger, in contrast to our

experience with acid rain and the ozone layer, the financial,

humanitarian and environmental price of decarbonizing the energy

supply is proving much steeper than expected. Despite falling costs

of solar panels, the system cost of solar power, including land,

transmission, maintenance and nighttime backup, remains high. The

environmental impact of wind power—deforestation, killing of birds

of prey, mining of rare earth metals—is worse than expected.

According to the BP Statistical Review of World

Energy, these two sources of power provided, between them, just

1.35% of world energy in 2014, cutting emissions by even less than

that.

Indoor air pollution, caused mainly by cooking over wood fires

indoors, is the world’s biggest cause of environmental death. It

kills an estimated four million people every

year, as noted by the nonprofit science news website,

SciDev.Net. Getting fossil-fueled

electricity and gas to them is the cheapest and quickest way to

save their lives. To argue that the increasingly small risk of

dangerous climate change many decades hence is something they

should be more worried about is positively obscene.

August 7, 2015

The great filter

My Times column on the paradox that planets seem

to be abundant, but signs of life are rare:

The search for another world that can sustain life

is getting warmer. We now know of 1,879 planets outside the solar

system. A few weeks ago, we (the planetary we, that is: no thanks

to me) found Earth’s twin, a planet of similar size and a habitable

distance from its sun, but 1,400 light years from here. Last week

we found a rocky planet close to a star just

21 light years away, which means if anybody lives there and tunes

in to us, they could be watching the first episode

of Friends.

Also last week the Philae lander’s results showed that the comet it is riding on has

organic (carbon-based) molecules in its dust, the ingredients of

life. Even in our own solar system we know of a moon, Titan, where

it rains methane, and another, Europa, with an ice-covered ocean.

In short, it is getting ever more likely that there are lots of

bodies like Earth in our own galaxy alone: with liquid water and

the right sort of temperatures for the carbon chemistry of the kind

that life runs on here.

Which only underlines Enrico Fermi’s famous question, first

delivered over lunch at Los Alamos in 1950 during a conversation

about UFOs: “Where is everybody?” His point was that if there are

billions of habitable planets, and many have had billions of years

to produce intelligent life forms, then the chances are that some

of them must have had time to broadcast to, or even visit other

solar systems. So why is there not a whisper in the ether of their

version of Top Gear, let alone a glimpse of a

tentacled Clarkson careering through the air in a flying saucer, or

even a bit of ancient, rusty wreckage to show where he once

crashed?

The Fermi paradox gets ever more baffling, as the evidence grows

of other habitable planets. The silence is beginning to seem

ominous. Robin Hanson, the chief scientist of the prediction market

research firm Consensus Point, advises: “Take a minute to look up at the dark

night sky, see the vast, ancient and unbroken deadlands, and be

very afraid.” He thinks there may be an obstacle ahead of us that

has caused every previous planetary civilisation to collapse before

colonising the galaxy: nuclear war, or something equally

horrible.

He calls this argument the great filter, and defines it thus, “The sum total of all of the obstacles

that stand in the way of a simple dead planet (or similar sized

material) proceeding to give rise to a cosmologically visible

civilisation.” Have we got past the great obstacles, or are there

still some insuperable ones ahead?

We’ve certainly got through at least five big filters. First,

life evolved. Nick Lane in his magnificent new book The

Vital Question thinks that a peculiar feature of all earthly

life — that it traps energy in the form of protons pumped across

membranes — indicates that it began at warm alkaline vents on the

floor of the early ocean. Gradually that energy came to be used to

make information, in the form of genes, and the machinery to

replicate it.

Genetically and biochemically, there is only one form of life on

this planet, which might imply that it’s a rare and lucky accident,

but then later forms would have struggled to compete with the first

one, so it’s not clear how difficult this step was and how many

planets with the right conditions failed to take it. That life did

not then die out thanks to a global freeze-up or fry-up may have

depended — David Waltham argues in his book Lucky

Planet— on the good fortune of having a relatively large

moon that stabilised our spin and moderated our climate: another

possible stroke of luck that other planets perhaps did not

share.

Next, after a couple of billion years, creatures bigger than

microbes emerged, once (Nick Lane argues) an energy-per-gene limit

was breached by the invention of the mitochondrion, a specialised

energy-generating microbe living inside another cell. This gave us

large and complex cells of the kind found in plants, animals and

fungi, and eventually multicellular creatures making and using

oxygen. It took a very long time to achieve this step, so many

planets may have been filtered out at that stage, and be stuck with

microbes only.

Earth, then, had complex life forms for more than half a billion

years before anything remotely intelligent enough to develop

technology appeared. For 140 million years, the dinosaurs achieved

large size and nimble agility without ever threatening to do much

mental or physical (as opposed to genetic) innovation. Their

evolutionary experiment was cut short by a meteorite, and the

mammals took another 60 million years even to start on technology.

Even then, it was only one species, a primate, that became

technological, rather than the almost equally large-brained

dolphins. So that was a strong filter: intelligence without

technology is clearly possible.

Even once we had big brains, technology, language and culture,

human ancestors spent a few million years stuck in

hunter-gathering, before something triggered an explosion of

cumulative culture in one sub-species on one part of one continent,

Africa, about 200,000 years ago. I have argued before that this

step was enabled by the invention of exchange and specialisation,

which made us capable of “cloud intelligence” so we could

collaboratively build devices too complex for individual minds to

comprehend. Only then did we experience rapid cultural evolution

and innovate to the point where we could start exploring space.

It is, in other words, very likely that most planets would have

failed to clear all these hurdles, which may explain the silence.

Many may teem with microbes; others could be rich in fossils of

life that died out; a few possibly host herds of agile, even

ingenious, creatures, some of which communicate in languages; one

or two might have got to the point of inventing weapons of war

before some catastrophe intervened. But almost none have reached

the point where they could send messages and spacecraft out of

their atmospheres.

Is it not incredibly lucky that we live on a rare planet that

did make it? Well, no, because whoever lived on such a planet would

say that about themselves. It is for this reason that I am not

persuaded yet that the most severe filter, the one that stops most

planets colonising the galaxy, comes after the stage we have

reached. I think that’s unnecessary pessimism. And with that I am

off on a summer holiday.

Matt Ridley's Blog

- Matt Ridley's profile

- 2180 followers