Matt Ridley's Blog, page 3

December 7, 2021

Help Viral Hit Best Seller Lists, Win a Signed Copy

Thanks to your help, my new book Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19, co-authored with MIT scientist Alina Chan, is picking up a lot of steam in America.

As I have mentioned before, I co-authored Viral—which tells the fascinating and heroic story of those searching for the origin of the pandemic, despite the challenges brought by those who don't want us to know—simply because I think finding that origin is the most important issue facing the world right now. And for that reason, Alina and I have been asking for your help making the book a success.

So far, your help has been wonderfully effective.

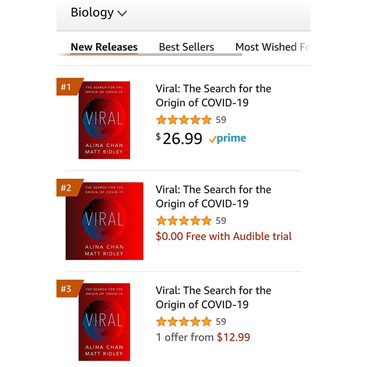

It nearly hit the top 100 (of all editions of all books, including fiction, children's books, etc.) on Amazon.com, hit the top ten of new non-fiction books, and is each of the top three places in new biology books! I recently discussed it on one of the most-watched cable shows in the US, and copies have been requested by at least two members of the United States Senate (one from each party), at least one member of Congress, and one state governor.

This means there is a chance it could reach one of the New York Times or Wall Street Journal best seller lists (for example, for hardcover non-fiction) for this week, which of course would give the book an even wider reach, and help spread even more light on the search for the pandemic's origin.

So, if you want to help, please consider...

Ordering it now if you're planning to but haven't yet, or you know someone who would appreciate it as a gift.

Leaving a review or rating on Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, or elsewhere once you've read it.

Telling others what you think as well, whether in-person or online.

eight personalised, Signed copies

As a small thanks, I'm going to send out eight personalised, signed copies to those of you helping us make Viral a success.

Four will go to those who pre-ordered or ordered in the weeks following release, and the other four will go to those of you who help us spread the word on social media.

Order Viral in the US: Amazon, other retailers like Barnes & Noble, or support independent booksellers by using bookshop.org

Order Viral in the UK: Amazon.co.uk, other retailers like Waterstones, or from uk.bookshop.org

It's also available in Australia, Canada, India, and many other places.

To become eligible...

Purchase a copy now (if you haven't already), and submit your proof of purchase here: bit.ly/ViralSigned

or retweet this tweet

or like the new Viral Facebook page

And yes, you can do all of the above to increase your chances!

We will accept entries until the 10pm GMT tomorrow, Friday, 10th December (5pm ET / 2pm PT in North America) and contact the winners within two hours after.

Thank you so much for your wonderful support, and especially for your help bringing light to this vital issue.

Matt Ridley's latest book Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19, co-authored with scientist Alina Chan from Harvard and MIT's Broad Institute, is now available—in the United States, in the United Kingdom, and elsewhere.

Discuss this article on Matt's Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter profiles.

You can also stay updated by subscribing to Matt's newsletter and by following the new Viral Facebook page.

November 30, 2021

The Government is still fighting the wrong war on Covid-19

Here we go again, fighting the last war. Because governments are perceived to have moved too slowly to ban flights when the delta variant arose in India, we jumped into action this time, punishing the poor South Africans for their molecular vigilance. But nothing was going to stop the delta going global, and the latest set of government measures to stop the spread of the new omicron variant are about as likely to succeed as the Maginot line was to stop General Guderian’s tanks. The cat is already out of the bag. Just because we can take action does not make it the right thing to do.

This pandemic has mocked public-health experts. They told us to wash our hands and then realised it was spreading through the air. They told us masks were useless and then made them mandatory. They sent Covid cases to ordinary hospitals where they infected patients.

Banning flights might have stopped the Wuhan variant of SARS-CoV-2 right at the start had the Chinese authorities not insisted until mid-January 2020, along with the World Health Organisation, that the only way to catch the virus was from an infected animal. Since then, the virus has evolved to be ever more infectious. Alpha spread twice as fast as the original Wuhan strain; delta twice as fast as alpha, and omicron looks like it may have doubled that speed again.

Worryingly, Omicron may itself have emerged as a result of modern treatments offered to patients – in particular the use of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies as therapy. There is evidence that its mutations are concentrated in parts of the spike gene where they help it to evade such antibodies, which both reduces the effectiveness of the treatments and hints at how the mutations arose. Maybe such mutations would not have occurred in a previous era.

Lockdowns are another example. Before the internet, and online retail, locking down the freedoms of healthy people was never an option. Yes, lockdowns slowed the spread but at severe psychological, economic and human cost, and worryingly, one of those costs may have been to prevent the virus evolving to be milder. In the spring of 2020, a strain that caused a severe case of covid was more likely to be passed on (because the victim went to hospital) than a mild case (where the victim stayed locked down at home). Much the same happened in 1918; severe flu cases got evacuated from the trenches to crowded hospitals, while mild cases did not, and in August 1918 the virus became more deadly.

It is no coincidence that there are about 200 kinds of virus that cause the common cold, yet none are dangerous. The perfect recipe for a respiratory virus is to stay in the cool cells of the nose and throat lining and not cause systemic illness that would cause the host to cancel his or her plans. Unlike viruses transmitted by insects, sex or water, respiratory viruses generally do evolve to be mild but highly infectious.

In the 1918 flu pandemic or the “Russian flu” of 1889-90 (which some biologists think was a coronavirus), there were two waves of deaths, then the pathogen settled down to be endemic and mild. I fear – though of course I might be wrong – that our policies this time have saved lives at first but delayed a similar taming of the virus. Evolution is not just mutation: it’s mutation plus selection caused by competition between strains for susceptible hosts.

With luck, omicron will prove to be not only more infectious but also milder than delta. According to the doctor who diagnosed it, omicron “presents mild disease with symptoms being sore muscles and tiredness for a day or two… They might have a slight cough.” This, plus the effect of the vaccines, means that Britain’s policy of opening up in July, defying the modellers’ apocalyptic obsessions, proved sensible. The virus did not spiral out of control, or overwhelm the NHS, but a series of small waves came and went, as society inched towards an endemic truce with the enemy.

The knowledge that we possess about this virus is truly extraordinary. Compared with even two decades ago, we can read its genome, trace its ancestry, map its mutations, predict its characteristics and understand its biochemistry in stunning detail. But this has profited us little. Our ability to stop it in its tracks – vaccines aside – is barely above the mediaeval. Would the course of pandemic have been better or worse if we could not take tests, model curves or differentiate mutant strains? I am not sure. Like Cassandra we are cursed to see the truth, but not be able to act on it.

Matt Ridley's latest book Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19, co-authored with scientist Alina Chan from Harvard and MIT's Broad Institute, is now available—in the United States, in the United Kingdom, and elsewhere.

Discuss this article on Matt's Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter profiles.

You can also stay updated by subscribing to Matt's newsletter and by following the new Viral Facebook page.

November 26, 2021

It’s a danger to the world that the precise origin of Covid-19 remains a mystery

It is almost exactly two years since the pandemic began. According to an official document seen by the South China Morning Post, the first retrospectively diagnosed case of Covid in Wuhan was on November 17 2019, while genetic analysis points to a similar date, November 18. (The so-called “patient zero” discussed in the media this week has been known about for months and is very unlikely to be the first case even according to the World Health Organisation.)

In the case of Sars, 19 years ago, and Mers, nine years ago, the first known cases were followed within a couple of months by unambiguous clues as to how the virus jumped from an animal source into people. Both viruses live naturally in bats, which had somehow infected intermediate animal hosts such as palm civets and camels before transmitting into people.

Yet in the case of Sars-CoV-2, despite the fact that genetic testing technologies have advanced by leaps and bounds, we have no clear pattern of early cases stemming from an animal source. Dr Michael Worobey’s analysis this week pointing to a patient with symptom onset on December 11 who was a seafood vendor in the market is consistent with the Chinese authorities’ conclusion in May 2020 that the market was the site of a superspreader event, not the source. The positive samples from surfaces in the market show no correlation with the sale of wildlife products.

Meanwhile, there are still no cases of an original animal host found to be carrying this virus. Closely related viruses have been found in bats, and in three smuggled pangolins, but none are close enough to be direct progenitors of the pandemic. This is despite the testing of 80,000 animals in China and close to 2,000 animals from the wildlife trade between 2017 and 2021. The trail has gone cold.

That’s odd. If there was a smoking gun in the wet markets of Wuhan we should know by now, and the lack of urgency shown by the Chinese authorities in stamping out the wildlife trade (plus their decision in September to blame a laboratory in North Carolina) suggests they don’t think the answer lies in the wildlife trade either.

Having just published a book on this mystery, with Alina Chan, I am surprised by how many people ask me why it matters, given that an admission from Beijing is unlikely. Some even argue that it would be better if we do not find out how it started in case the truth leads to a row with China.

Finding the origin of Covid matters because the virus has now probably killed an estimated 16 million people, and we owe it to them and their families to investigate. It matters because bad actors – terrorists and rogue states – are watching the episode and wondering what they can get away with in terms of bioterrorism or pathogen research. And it matters because we need to know how to prevent the next pandemic.

If this pandemic began with the food trade, changes must be made there to prevent another. If it began with products used in traditional Chinese medicine, a set of practices endorsed by the World Health Organisation in 2019 at the urging of Xi Jinping, that needs revisiting. And if the pandemic began as a result of risky virology research, that category of work needs to be made safer. Wuhan is the site of the world’s most active research programme on Sars-like viruses, and viruses have escaped from labs many times.

Here is a description of one of the experiments carried out in Wuhan a few years ago. Samples taken from bats in a cave in Yunnan were analysed for viruses closely related to Sars. One of the viruses was used to infect human cells in the lab at biosecurity level 2 (meaning that sometimes the only protection was gloves, basically). It was engineered to carry the spike gene of each of various other Sars-like viruses that had been collected – with the aim of finding out how capable those other viruses were of infecting human cells.

The engineered viruses were then used to infect “humanised” mice – mice with the human ACE2 viral entry receptor gene. In some cases they produced viral loads several orders of magnitude greater than the original natural virus in the lungs and brains of the humanised mice, sometimes killing more of the mice.

At the very least such experiments failed in their ostensible purpose: to predict the next pandemic. At worst, they may have caused it. Yet the US government money going into such work continues to flow in the millions.

Until we can rule out a laboratory origin for Covid, we must act as if it may have happened. The world needs to come together with a pandemic treaty, agreeing to limit this risky pathogen research, agreeing to transparent sharing of data during a pandemic and agreeing to sanction those countries that refuse to sign up to such a treaty.

Matt Ridley's latest book Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19, co-authored with scientist Alina Chan from Harvard and MIT's Broad Institute, is now available—in the United States, in the United Kingdom, and elsewhere.

Discuss this article on Matt's Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter profiles.

You can also stay updated by subscribing to Matt's newsletter and by following the new Viral Facebook page.

November 22, 2021

My Latest Book, Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19, Is Now Available

If you don't subscribe to the new newsletter or follow me on Facebook and Twitter, you may not have heard: My new book Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19, co-authored with the young and brilliant scientist Alina Chan, published this day last week and is now available to purchase.

Less than a week before that, Alina and I met in person for the first time, which you can watch on my YouTube channel.

We explore both natural spillover and lab leak possibilities in depth—and share which we determined, over the course of writing it, to be more likely.

It was a challenging, frustrating, intriguing journey.

Here are some of the places you can pick it up...

On Amazon in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, India, and many other countries.

The publisher's website lists other major retailers in both the US and in the UK if you'd prefer not to use Amazon.

You can also use bookshop.org and uk.bookshop.org to support an independent bookseller when making your purchase.

The Covid-19 pandemic has killed at least five million people and counting. The impact can also be measured in weddings and gatherings cancelled, jobs lost and businesses bankrupted, schools closed and parents balancing childcare and work, clinical visits missed and treatments put on hold, and innumerable people living more isolated lives than before. It has created medical, social, psychological, and economic misery on a scale unprecedented in peacetime.

If we do not find out how this pandemic began, we are not only setting a dangerous precedent. We are also ill-equipped to know when, where and how the next pandemic may start.

In other words: The origin of Covid matters.

That's why I hope you will not only read Viral, but help Alina and I make it a success.

Here are some ways you can do so:

Order it now instead of waiting, which will help it reach best seller lists and rank higher on Amazon, and tells the online algorithms to recommend it to others.

Rate and review it, on Amazon or elsewhere, once you've finished it.

Share and engage with our posts about it on Twitter, on Facebook, and on other social media platforms.

Use the #OriginOfCovid hashtag to post about it.

It was a privilege to help Alina write the book which could help us find and share the truth—if it is a success.

Thank you, as always, for your wonderful support.

Matt Ridley's latest book Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19, co-authored with scientist Alina Chan from Harvard and MIT's Broad Institute, is now available in the United States, in the United Kingdom, and elsewhere.

Discuss this article on Matt's Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter profiles. You can also stay updated by subscribing to Matt's newsletter and by following the new Viral Facebook page.

November 21, 2021

The Covid lab leak theory just got even stronger

My article for Spectator:

Two years in, there is no doubt the Covid pandemic began in the Chinese city of Wuhan. But there is also little doubt that the bat carrying the progenitor of the virus lived somewhere else.

Central to the mystery of Covid’s origin is how a virus normally found in horseshoe bats in caves in the far south of China or south-east Asia turned up in a city a thousand miles north. New evidence suggests that part of the answer might lie in Laos.

The search for viruses closely related to Sars-CoV-2 took a new turn in September when a team of French and Laotian scientists found one in a horseshoe bat living in a cave in the west Laotian province of Vientiane. Other related viruses had been found in Cambodia, Thailand, Japan and elsewhere in China, but this one, Banal-52, was different. For the first time since the pandemic began, this was a virus genetically closer to the human Sars-CoV-2 virus than one called RaTG13, collected in southern Yunnan in 2013. RaTG13, which had been stored for six years in a freezer in a lab in Wuhan itself, is genetically 96.1 per cent the same as Sars-CoV-2; Laos’s Banal-52 is 96.8 per cent.

The discovery of Banal-52 was greeted with relief by champions of the theory that the virus must have jumped into people in a natural spillover event, not an accident inside a laboratory. If Covid’s closest cousins are flitting about in bats in south-east Asia, then that sample in the freezer in Wuhan looks less suspicious. ‘I am more convinced than ever that Sars-CoV-2 has a natural origin,’ said Linfa Wang of Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, a close collaborator of the Wuhan scientists.

True, the Laos virus lacked a critical feature in a key part of a key gene that makes Covid so infectious: a special 12-letter segment of genetic text called a furin cleavage site. It’s a feature that has never been seen in a Sars-like virus, except for Sars-CoV-2. Apart from that, it seemed that the Laotian virus might have knocked the burden of proof back across the philosophical net into the court of the proponents of lab-leak.

Then last month a bunch of emails, uncovered by a lawsuit from the so-called White Coat Waste Project, returned the ball right back over the net. They comprised an exchange between the American virus--hunting foundation, the EcoHealth Alliance and its funders in the US government. The scientists discussed collecting viruses from bats in eight countries including Burma, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos between 2016 and 2019. But to avoid the complication of signing up local subcontractors to their grants in those countries, they promised to send the samples to a laboratory they already funded. And where was this lab? Wuhan.

Some of the emails talk about sending data, not samples; but some talk repeatedly about sending actual samples. ‘All samples collected would be tested at the Wuhan Institute of Virology,’ reads one from 2016. Another in 2018 even talks of sending bats themselves. The emails make it clear that Wuhan scientists would sometimes be working in the field alongside their US colleagues.

Remember the central issue is how a bat virus got to Wuhan. So now, in both Yunnan and Laos, the only people who knowingly transported bat virus samples to Wuhan — and only to Wuhan — were scientists. Gilles Demaneuf, a New Zealand-based data scientist who’s been analysing this issue, says the natural spillover theory has ‘no explanation for why this would result in an outbreak in Wuhan of all places, and nowhere else’.

As for that missing furin cleavage site, another leaked document revealed in September by Drastic, a confederation of open-source analysts like Demaneuf, sent shock- waves through the scientific community. Dr Peter Daszak, head of the EcoHealth Alliance, spelled out plans to work with his collaborators in Wuhan and elsewhere to artificially insert novel, rare cleavage sites into novel Sars-like coronaviruses collected in the field, so as to better understand the biological function of cleavage sites. His 2018 request for $14.2 million from the Pentagon to do this was turned down amid uneasiness that it was too risky; but the very fact that he was proposing it was alarming.

Most of the funding for the Wuhan Institute of Virology comes from the Chinese not the American government, after all; so the failure to win the US grant may not have prevented the work being done. More-over, exactly such an experiment had already been done with a different kind of coronavirus by — guess who? — the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

It is almost beyond belief that Dr Daszak had not volunteered this critical information. He played a leading role in trying to dismiss the lab-leak idea as a ‘conspiracy theory’, using his membership of the WHO-China investigation to support the far-fetched theory that the virus reached Wuhan on frozen food.

If the trail to the source of the pandemic leads through Laos, it is possible western countries can find out more. The Chinese government has blocked anybody who tries to get near to the mineshaft in Yunnan where RaTG13 was found. But now that we know the US government was funding virus sampling in Laos, the EcoHealth Alliance should be required to report in full on exactly what was found. Saying ‘Oh, that data belongs to the Chinese now’ is not good enough. American taxpayers funded the work. Belatedly, the US National Institutes of Health has requested more information.

The Wuhan Institute had a database of 22,257 samples, mostly from bats, but took it offline on 12 September 2019, supposedly because somebody was trying to hack into it. The lab has published few details of viruses collected after 2015, so details of any found in Laos since then are presumably in that database. Dr Daszak says he knows what’s there and it’s of no relevance. Yet he refused even to request that the Wuhan Institute release it, despite his close relationship with the scientists in question.

But even finding relevant viruses in Laos still won’t answer the question of how they got loose in Wuhan. And with the continuing failure to find any evidence of infected animals for sale in Chinese markets, the astonishing truth remains this: the outbreak happened in a city with the world’s largest research programme on bat-borne corona-viruses, whose scientists had gone to at least two places where these Sars-CoV-2-like viruses live, and brought them back to Wuhan — and to nowhere else.

Matt Ridley's latest book Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid-19, co-authored with scientist Alina Chan from Harvard and MIT's Broad Institute, is now available in the United States, in the United Kingdom, and elsewhere.

Discuss this article on Matt's Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter profiles. You can also stay updated by subscribing to Matt's newsletter and by following the new Viral Facebook page.

October 24, 2021

China is using the climate as a bargaining chip

China’s President Xi Jinping has apparently not yet decided whether to travel to Glasgow next month for the big climate conference known as COP26. That is no doubt partly because he’s heard about the weather in Glasgow in November, and partly because he knows the whole thing will be a waste of his time. After all, the fact that it is the 26th such meeting and none of the previous 25 solved the problem they set out to solve suggests the odds are that the event will be the flop on the Clyde.

But another reason he is hesitating was stated pretty explicitly by his Foreign Minister, Wang Yi: ‘Climate cooperation cannot be separated from the general environment of China-US relations.’ Roughly translated, this reads: we will go along with your climate posturing if you stop talking about the possibility that Covid-19 started in a Wuhan laboratory, about our lack of cooperation investigating that origin, or about what we are doing to Hong Kong or the Uighur people.

The Chinese Communist Party is using the COP as a bargaining chip. To keep us keen, Xi announced last month that China would stop funding coal-fired power stations abroad. ‘I welcome President Xi’s commitment to stop building new coal projects abroad — a key topic of my discussions during my visit to China,’ enthused Alok Sharma, the president of COP26. ‘A great contribution,’ said John Kerry, the United States climate envoy.

In truth, Xi is throwing us a pretty flimsy bone. He did not say when he would stop funding overseas coal or whether projects in the pipeline would be affected, so the impact on the world’s coal consumption will be minimal. And the gigantic expansion of coal burning in China itself continues. It already has more than 1,000 gigawatts of coal power, and has another 105 gigawatts in the pipeline. (Britain’s entire electricity generational capacity is about 75 gigawatts.)

China now burns half the world’s coal. According to the US Energy Information Administration, China is tripling its capacity to make fuel out of coal, about the most carbon-intensive process anybody can imagine. For reasons that are not clear, many western environmentalists are mad keen on China, despite its gargantuan appetite for coal, and won’t hear a word against the regime.

So it is only fair to ask just what concessions Britain and America have made to try to entice China into being helpful in Glasgow — and whether they are worth it. Was it a coincidence that a few weeks before Xi’s announcement, the Biden administration put out a report from its intelligence community that concluded it could not be sure either way whether the virus came out of the laboratory? The report had all the hallmarks of having been watered down for political reasons. Joe Biden, Kamala Harris and John Kerry have carefully avoided mentioning China in recent speeches about human rights.

Likewise, was it a coincidence that there has been barely a peep recently out of the British government as the last vestiges of liberty are extinguished in Hong Kong? Even after China’s government slapped sanctions on British parliamentarians, sanctions against Chinese Communist party officials or the Hong Kong government are conspicuous by their absence. That the COP was delayed for a year doubled its value to China as a bargaining chip.

I am not suggesting there is an explicit policy of appeasement, but that politicians would not be human if they did not hesitate when deciding whether to be even mildly critical on these issues at a time when they badly want helpful Chinese announcements on climate policy to avert a flop. And China’s politicians would not be human if they did not exploit this. So it is worth asking whether the game is worth the candle.

After all, the history of these conferences is that they cost a fortune and attract tens of thousands of well-paid activists who talk all night and then announce something so meaningless they might as well not have bothered. There was the Kyoto Protocol (1997), which everybody signed and everybody ignored; the Bali Action Plan (2007), which merely recognised that ‘deep cuts in global emissions will be required’; the Copenhagen Accord (2009), which was just a bit of paper; the Cancun Agreements (2010), which agreed to set up — but not to fund — a fund. And these were the ones that claimed to achieve something.

For a moment, the Durban conference of 2011 looked different in that it agreed there would be enforceable emissions commitments from all parties by 2015. Nothing less than legally binding promises would do at Paris in 2015, we were told. As Paris approached, it became clear that America, China and India would sign no such binding commitments, so some genius came up with plan B: everybody would make a legally binding commitment to come up with non-legally-binding commitments to cut emissions. This was presented to a gullible media as a triumph. When I pointed out this sleight of hand in parliament, a government minister compared me to the North Korean regime, a low point in my respect for my party.

China’s leaders have long ago decided that the climate issue is simply something they can use as leverage with the West. A few minor announcements about more spending on solar power or less money for coal in Africa are a small price to pay for the West’s relative silence on human rights in Hong Kong, the release of the Huawei finance director in Canada and some easing of tariffs and sanctions. It’s a double whammy win for China: it cannot believe its luck as it watches us closing down our reliable and affordable power sources to buy from them wind turbines, solar panels and ingredients for batteries for electric cars.

Currently, the Chinese strategy is to divide and rule: they are all charm with Brits and all snarl with Americans and Australians. The Aussies got slapped with trade sanctions just for asking for an inquiry into how the pandemic started. The Chinese Communist party newspaper the Global Times last month let it be known that it finds Britain more amenable than ‘erratic’ America: ‘Comparing with Kerry, Sharma showed a more readily cooperative attitude,’ it wrote, schoolmaster-style, and quoted the Foreign Minister as saying that Britain ‘won’t be as domineering as the US in talks with China over climate change cooperation, which will be used as a way to improve its deteriorating relations with China and secure the Chinese market after Brexit’.

In a forthcoming paper for the Global Warming Policy Foundation, Professor Jun Arima of Tokyo University, who was one of Japan’s chief climate negotiators, warns that: ‘The divided and acrimonious world that is being created by net zero policies will permit China to further enhance its global economic presence and influence while the developed, democratic world becomes economically, politically, and militarily weaker.’

Share your comments on Matt's Facebook and Twitter profiles. Stay updated on new content by following him there, and then subscribing to his new newsletter.

Matt's upcoming book with Alina Chan Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid is now available to pre-order in the US, in the UK, and elsewhere, both on Amazon and at many independent bookshops.

How Innovation Works by Matt Ridley is now available in paperback, and the first chapter is still available to download for free.

October 18, 2021

How to rev up the UK's innovation engine

My blog for the Radix think tank:

I was pleased to speak at the recent Radix Big Tent Meet the Leaders session about innovation, a topic that is close to my heart and one of great importance.

Innovation is the source of all prosperity. It is the reason countries get rich in the first place and so the more you have of it the better. We should be thinking hard and furiously about how to turn ourselves back into the country that spawned the industrial revolution.

One of the key elements that is required for innovation to flourish is freedom. By that I mean the freedom for trial and error, particularly the freedom to experiment, to be wrong, to fail, to start again. This freedom for entrepreneurs was a feature of 17th to 19th century Britain, not just the North East where I live, but across the UK, making it quite distinct from continental Europe (except Holland).

I believe this economic freedom is also the key to understanding China, because one of the reasons for China’s economic success is that – although not free politically – it has been free economically for entrepreneurs, at least until recently. There is an important lesson for the UK.

In my research for my book on innovation, trial and error was a recurring theme from the stories I collected. For example, Jeff Bezos made a string of catastrophic errors at Amazon and he boasts about it and he says if you’re not swinging and missing, you’re not swinging enough. Without that experimentation, Amazon wouldn’t be the company that it is today.

When we talk about innovation, the focus is too much on invention rather than innovation: we talk about the original prototype rather than the hard slog to turn it into something that’s affordable, reliable and available, which is a much more collective effort. A lot of the stories of innovation are actually about quite ordinary people, people who just knew the importance of learning by doing, of experimenting, as part of a collective effort by lots of people.

At my school, science was simply taught as these are the things we know for sure – those are what you need to know, instead of saying the whole point of science is that scientists are interested in the things they don’t know, the things they don’t yet understand, the mysteries, the enigmas and trying to solve them.

Somewhere in the education system, we should be challenging people to say to students that they’re not entering a complete world, a finished world, the world in which we know everything, a world in which we know how to run it. They are entering a world which is going to change fast, where things are going to be invented and innovated and they’re going to change the world. We should be telling them they could be part of it.

An area where we could do more to remove barriers to innovation in the UK is in biotechnology. The recent announcement that gene editing will be allowed for experimental purposes in plants in this country is good news, but from my point of view it’s not nearly bold enough. There’s a huge opportunity having left the European Union for the UK to say we’re going to be the European country that does this, but we’re still being cautious.

For example, take the breakthrough by the Roslin Institute on pig DNA that could make it immune to a disease, this technology is now being commercialised in other countries, but is a long way off from being allowed here in the UK. How is it that we got ourselves into a situation where we’re not even allowed to do an incredibly safe project on a pig, but we’re doing extremely dangerous projects on viruses?

Share your comments on Matt's Facebook and Twitter profiles. Stay updated on new content by following him there, and then subscribing to his new newsletter.

Matt's upcoming book with Alina Chan Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid is now available to pre-order in the US, in the UK, and elsewhere, both on Amazon and at many independent bookshops.

How Innovation Works by Matt Ridley is now available in paperback, and the first chapter is still available to download for free.

We're wasting our big Brexit gene-editing opportunity

My article, for The Telegraph:

The Government wants to unleash innovation. If it were to be presented with a magic wand that could by 2040 feed millions more people, avoid tens of millions of tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions and improve biodiversity on hundreds of thousands of hectares, while benefiting the economy and reducing the footprint of farming, it would surely grab it.

That is exactly what Crispr and other gene editing technologies promise for agriculture, based on what they are doing elsewhere. Yet the Government’s first moves towards allowing gene editing, now that we are free from the EU’s stifling restrictions on it, while welcome, are frustratingly hesitant.

Crispr will be encouraged, according to plans released last month, but only at first in plants and not animals. This is disappointing because, in a world first, a British company, Genus, has funded research at a British research institute, Roslin, near Edinburgh, to remove a tiny segment of DNA from the genome of pigs and thus render them almost wholly resistant to a very nasty disease called porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS). The pigs are completely healthy in every other way.

Because nothing is added to the pig genome during this process there is not even the theoretical possibility of some unintended consequence, as there is with cross breeding or (in the case of plants) the deliberate mutation of genes at random with gamma rays. Genus will soon have approval to market these pigs in Mexico, China and America, but not here. British pigs and British pork consumers will be at an economic and medical disadvantage. The rest of the world is amazed.

Absurdly, the only remaining smidgen of opposition to this innovation, from green extremists, is that somehow if pigs are less likely to catch disease then farmers will treat them less well. No, I can’t follow the logic either. Yet it looks like somebody got to the Government and persuaded it to postpone a decision on animals.

Where crops are concerned, countries that are encouraging new breeding techniques, including Crispr and genetic modification, are experiencing increased productivity and competitiveness, increased farm incomes, increased biodiversity on farms, decreased pesticide use, decreased need for land for farming (which spares land for nature), widespread acceptance of the products and a plethora of small firms and universities collaborating on projects to improve the nutritional quality of niche crops. Argentina, for example, has seen a rash of small new start-ups in gene editing.

Europe – to which we have remained partly in thrall on this issue despite Brexit – has missed out on all this bounty, its farming more dependent on chemicals, subsidies, commodity crops and big business than it would otherwise be.

The worries that panicked governments 20 years ago into raising high barriers against biotechnology have proved to be wholly without foundation. Any risks to human health and the environment from biotech have been handsomely outweighed by benefits. But instead of learning the lesson that you should stand up to eco-bullies, I fear today’s politicians have chosen to be ultra-cautious. This only allows the irrational extremists more time to organise (remember shale gas) and puts more barriers to entry in the way of small business and niche products.

It remains the absurd truth that if you were to generate a new blight-resistant potato by bombarding its genes with gamma rays, a technology that Greenpeace and its ilk have never campaigned against merely because it was invented 70 years ago, you are much more lightly regulated as you try to get it to market than if you generate an identical potato by snipping out or inserting a tiny piece of DNA with Crispr. Why? What matters is whether the potato is safe.

Indeed, it is not too fanciful to suggest that the way we have regulated biotechnology has actually increased risks. Suppose somebody did propose a genuinely dangerous experiment – taking genes from anthrax bacteria and putting them in wheat, say. They would encounter hurdles no higher than if they wanted to make a blight-resistant potato by snipping out a segment of DNA. That’s like making somebody get an HGV licence before playing in dodgem cars. After all, high-stakes “gain of function” experiments on viruses with artificially increased infectivity and virulence are, we now know, happening routinely in some laboratories in China and America. Yet we worry about potatoes.

Britain pioneered a lot of plant and animal science, it has a first-class plant-variety licensing system with a perfect record of safety and it led the way in developing much plant and animal biotechnology, but it has since had to watch the rest of the world commercialise the work and reap the rewards. What it lacks is not good research experiments, but a clear path to rapid and proportionate approval of new crop and animal varieties developed with the latest techniques so as to kick-start some crucial commercial projects that could have immensely beneficial effects.

Share your comments on Matt's Facebook and Twitter profiles. Stay updated on new content by following him there, and then subscribing to his new newsletter.

Matt's upcoming book with Alina Chan Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid is now available to pre-order in the US, in the UK, and elsewhere, both on Amazon and at many independent bookshops.

How Innovation Works by Matt Ridley is now available in paperback, and the first chapter is still available to download for free.

September 24, 2021

The Root of the Energy Crisis

My article for The Daily Mail:

Had it not been so exceptionally calm in the run up to this autumn equinox, one could call the energy crisis a perfect storm. Wind farms stand idle for days on end, a fire interrupts a vital cable from France, a combination of post-Covid economic recovery and Russia tightening supply means the gas price has shot through the roof – and so the market price of both home heating and electricity is rocketing.

But the root of the crisis lies in the monomaniacal way in which this government and its recent predecessors have pursued decarbonisation at the expense of other priorities including reliability and affordability of energy.

It is almost tragi-comic that this crisis is happening while Boris Johnson is in New York, futilely trying to persuade an incredulous world to join us in committing eco self-harm by adopting a rigid policy of net zero by 2050 – a target that is almost certainly not achievable without deeply hurting the British economy and the lives of ordinary people, and which will only make the slightest difference to the climate anyway, given that the UK produces a meagre 1 per cent of global emissions.

As for the middle-class Extinction Rebellion poseurs and their road-closing chums from Insult Britain, sorry Insulate Britain, they are basing their apocalyptic predictions of ‘catastrophe’ and billions of deaths on gross exaggerations. And while preventing working people earning a livelihood may make them feel good, it does nothing to solve the real problem of climate change.

Yet this crisis is a mere harbinger of the candle-lit future that awaits us if we do not change course.

It comes upon us when we have barely started ripping out our gas boilers to make way for the expensive and inefficient heat pumps the Government is telling us to buy, or building the costly new power stations that will be needed to charge the electric cars we will all soon require.

When David Cameron’s energy bill was being discussed in Parliament in 2013, the word on everybody’s lips was ‘trilemma’: how to ensure that energy was affordable, reliable and low-carbon. Everybody knew then that renewables were unreliable: that wind power fully works less than one-third of the time, and that solar power is unavailable at night (of course) and less efficient on cloudy winter days. Yet whenever we troublemakers raised this issue, we were told not to worry – it would resolve itself, they said, either because wind is usually blowing somewhere, or through the development of electricity storage in giant battery farms. This was plain wrong. The task of balancing the grid and maintaining electrical frequency has grown dangerously the more reliant on wind power we have become – as demonstrated by the widespread power cuts of August 2019. The cost of grid management has soared to nearly £2billion a year in the last two decades.

Wind can indeed be light everywhere and the grid still needs vast extra investment to transfer wind power from northern Scotland to southern England. One of the cables built at huge expense to do just that has failed multiple times and Scottish wind farms are frequently paid extra to switch off because there’s not enough capacity in the cables.

As for batteries, it would take billions of pounds to build ones that could keep the lights on for a few hours let alone a week.

So the only way to make renewables reliable is to back them up, expensively, with some other power source, responding to fluctuations in demand and supply.

Nuclear is no good at that: its operations are slow to start and stop. So, ironically, renewables have only hastened the decline of nuclear power, their even lower-carbon rival (remember it takes 150 tonnes of coal to make a wind turbine). And in any case, an inflexible approach to regulation has caused the cost of new nuclear to balloon – despite it being perhaps the most obvious solution to our long-term energy needs.

Coal – the cheapest option and the only energy source with low-cost storage in the shape of a big heap of the stuff – was ruled out as too carbon-rich, even though countries such as China are currently building scores of new coal-fired plants. Unlike those countries, the UK Government has rushed to close its remaining coal power stations – and banned the opening of a opencast coalmine at Highthorn on the Northumberland coast last year, despite it winning the support of the county council, the planning inspector and the courts when the Government appealed.

Ministers decided they would rather throw hundreds of Northern workers out of a job, turn down hundreds of millions of pounds of investment and rely instead – for the five million tonnes of coal per year gap that we still need for industry – on energy imports from those famously reliable partners, Russia and Venezuela.

To add insult to injury, the Government has been handing out hefty subsidies to a coal-fired power station in Yorkshire, Drax, to burn wood instead of coal, imported from American forests, even though burning wood generates more emissions than coal per unit of electricity generated. The excuse is that trees regrow, so it’s ‘renewable’, which makes zero sense then you think it through (trees take decades to grow – and then we cut them down again anyway).

So that leaves gas with the task of keeping the lights on.

Gas turbines are fairly flexible to switch on and off as wind varies, they’re relatively cheap, highly efficient and much lower in emissions than wood, coal or oil. But until 2009, the conventional wisdom was that gas was going to run out soon.

Then came the shale gas revolution, pioneered in Texas. A flash in the pan, I was told by energy experts in this country: and ‘could never happen here anyway’. So Britain – whose North Sea gas was running out – watched on in snobbish disdain as America shot back up to become the world’s largest gas producer, with their gas prices one-quarter of ours, resulting in a gold-rush of industry and collapsing emissions as a result of a vast, home-grown supply of reliable, low-carbon energy.

We, meanwhile, decided to kowtow to organisations like Friends of the Earth, which despite being told by the Advertising Standards Authority to withdraw misleading claims about the extraction of shale gas, embarked on a campaign of misinformation, demanding ever more regulatory hurdles from an all-too-willing civil service. Nobody was more delighted than Vladimir Putin, who poured scorn on shale gas in interviews, and poured money into western environmentalists’ campaigns against it. The secretary general of Nato confirmed that Russia ‘engaged actively with so-called non-governmental organisations – environmental organisations working against shale gas – to maintain Europe’s dependence on imported Russian gas’.

By 2019, shale gas exploration in Britain was effectively dead, despite one of the biggest discoveries of gas-rich rocks yet found: the Bowland shale, a mile beneath Lancashire and Yorkshire.

Just imagine if we had stood up to the eco-bullies over shale gas. Northern England would now be as brimming with home-grown gas as parts of Pennsylvania and Texas. We would have lower energy prices than Europe, not higher, a rush of manufacturing jobs in areas such as Teesside and Cheshire, rocketing wealth, healthy export earnings, no reliance on Russian whims (they control the reliability of supply and the price we pay for imported electricity, as we are experiencing right now) – and no fear of the lights going out.

But in lieu of that, we could at least invest in gas-storage facilities, to cushion against the Moscow threat and any potential disruptions to supply. But no, we chose to close the biggest of them, Rough, off East Yorkshire, in 2017 and run down our gas storage to just under 2 per cent of annual demand, far lower than Germany, Italy, France and the Netherlands.

Why? Presumably because the only forms of energy that ministers and civil servants respect are wind and solar. Gas is so last-century, you know!

Yet your electricity bill is loaded with ‘green levies’ that in part go to reward the crony capitalists who operate wind farms to the tune of around £10billion a year and rising. Because energy is a bigger part of the household budget of poorer people than richer people, this is a regressive tax. Because of the price cap on domestic bills, these levies hit industrial users even harder than domestic, and thus put up the prices of products in shops and deter investment in jobs too.

In the past, coal gave Britain an affordable supply of electricity that was also reliable so long as the miners’ union allowed it to be. The market mechanisms introduced by Nigel Lawson in the 1980s gave us greater efficiency, the dash for gas, cheaper electricity, a highly reliable supply and falling emissions.

The central planning of the 2010s has given us among the most expensive energy on the planet, futile price caps, bankrupt energy suppliers, import dependence, rising worries about the reliability of supply and – because of the fading influence of nuclear power – not much prospect of further falls in emissions.

So, it’s time to tear up the failed policies of today. What would I do? Take a leaf out of Canada’s book and reform the regulation of nuclear power so that it favours newer, cheaper and even safer designs built in modular form on production lines rather than huge behemoths built like Egyptian pyramids by Chinese investors.

Look to America’s example and restart the shale gas industry fast. Do everything to encourage fusion, the almost infinitely productive technology that looks ready to go by 2040. And call the bluff of the inefficient wind and solar industries by ceasing to subsidise them.

Energy is not just another product: it’s what makes civilisation possible.

Share your comments on Matt's Facebook (/authormattridley) and Twitter (@mattwridley) profiles. Stay updated on new content by following him there, and then subscribing to his new newsletter.

Matt's upcoming book with Alina Chan Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid is now available to pre-order.

How Innovation Works by Matt Ridley is now available in paperback, in the US, Canada, the United Kingdom and elsewhere. The first chapter is available to download for free.

September 5, 2021

Dismantling the environmental theory for Covid’s origins

With a laboratory leak in Wuhan looking more and more likely as the source of the pandemic, the Chinese authorities are not the only ones dismayed. Western environmentalists had been hoping to turn the pandemic into a fable about humankind’s brutal rape of Gaia. Even if ‘wet’ wildlife markets and smuggled pangolins were exonerated in this case, they argued, and the outbreak came from some direct contact with bats, the moral lesson was ecological. Deforestation and climate change had left infected bats stressed and with nowhere to go but towns. Or it had driven desperate people into bat-infested caves in search of food or profit.

Green grandees were in no doubt of this moral lesson. ‘Nature is sending us a message. We have pushed nature into a corner, encroached on ecosystems,’ said Inger Andersen, head of the United Nations Environment Programme. The pandemic was ‘a reminder of the intimate and delicate relationship between people and planet,’ said the director-general of the World Health Organisation, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. ‘God always forgives, we forgive sometimes, but nature never forgives,’ added Pope Francis, enigmatically. ‘Climate change is a threat multiplier for pandemic diseases, and zoonotic diseases,’ said John Kerry. Covid-19 was ‘the product of an imbalance in man’s relationship with the natural world,’ said Boris Johnson. ‘Mother Nature… gave us fire and floods, she tried to warn us but in the end she took back control,’ tweeted Sarah, Duchess of York.

In July last year, 17 scientists, including Dr Peter Daszak, who collaborated with the Wuhan Institute of Virology and was keen to exonerate his friends there, wrote an article in Science magazine insisting that the main lesson of the pandemic was that deforestation must cease: ‘The clear link between deforestation and virus emergence suggests that a major effort to retain intact forest cover would have a large return on investment even if its only benefit was to reduce virus emergence events.’

There were three problems with this argument. First, there is no ‘clear link’ between epidemics and deforestation. Aids, Sars, Mers, Ebola, Nipah, Hendra, Zika — none of these virus outbreaks has been plausibly linked to forest clearance, let alone as the major cause of them. Second, deforestation has not only ceased in southern China but went into rapid reverse a generation ago. There is more forest every year. Third, people encounter bats less, not more, than they did in the past. Urbanisation has drained rural villages of people and given them other ways of making a living than cutting trees or catching bats.

The deforestation statistics are startling to anybody who listens only to green activists. In 2018 a team from the University of Maryland concluded: ‘We show that — contrary to the prevailing view that forest area has declined globally — tree cover has increased by 2.24 million km2.’ That’s 7 per cent more forest globally than in 1982. New forests have been planted and old ones have regenerated naturally, as the footprint of farming shrinks, thanks to better yields.

There is another factor at work too. All the world’s ecosystems have been getting greener for more than 35 years; in that time the planet has experienced ‘an increase in leaves on plants and trees equivalent in area to two times the continental United States,’ as Nasa puts it. Why? Because of carbon dioxide emissions. Plants grow faster, and need less rainfall, when carbon dioxide levels in the air are higher. CO2 is plant food. (That is one reason that during the last ice age, when CO2 levels fell very low, deserts expanded dramatically and vast dust storms swept the globe.)

True, much of the forest recovery has been in Europe and North America, whereas some tropical rainforests have continued to shrink because of logging. But even some of those forests are now expanding. Countries like Bangladesh have been rapidly increasing their tree cover. As for China, it is reforesting as fast as anywhere on the planet. ‘China alone accounts for 25 per cent of the global net increase in leaf area with only 6.6 per cent of global vegetated area,’ reports a team from Boston University in Nature magazine. The increases are especially marked in southern China, they find: the very area where Covid-19’s bat-infecting relatives live.

Climate scientists are nothing if not flexible, so a study by Cambridge University earlier this year purported to blame the pandemic not on the usual suspect of a decrease in vegetation-stressing bats, but on the opposite: an increase in vegetation leading to a greater diversity of bats in southern China. This is because the data shows that the climate there is very slightly warmer in winter (though not in summer) and wetter in summer than it was a century ago. The only problem with this study, I was astonished to find when I read it carefully, was that it used models to estimate the impact both of climate change on vegetation, and of vegetation changes on bat diversity, rather than actual data. It was models all the way down. This did not stop the media reporting the results as if they were facts. But note that the argument was the very opposite of the green grandees’ one: industrial emissions have made southern China more hospitable to bats.

The truth is that human beings did, and still do, a lot more encroaching on nature when poor and using preindustrial technology. Bushmeat — monkeys, rodents and other animals sold in markets, mainly in Africa — is a trade restricted to poor countries. In richer ones people prefer to buy poultry and pork from shops. Go further back and the massive extinctions of the Pleistocene megafauna (moas, mammoths, giant sloths, giant kangaroos etc) in North and South America, Australia, Madagascar and New Zealand were achieved by people with stone axes and bows and arrows. We Europeans ‘encroached’ on our last woolly rhinoceroses long before we invented the wheel, let alone the budget airline.

As for bats, they have moved into our houses because eaves make good roosts, not because we’ve driven them to it. But the bats that carry Sars and Sars-CoV-2 are horseshoe bats, which generally stick to natural caves. Anybody who thinks that visiting caves is a novel human habit has not been paying attention. Cavemen — the clue is in the name — were encountering bat roosts for hundreds of thousands of years.

As the archaeologist Professor Timothy Taylor of the Comenius University in Bratislava put it to me: ‘Prehistoric human beings have been almost everywhere before us. Perhaps not to the top of Everest or to Antarctica, but certainly underground wherever they could: out of curiosity; for rituals; for potting clay; for lithic resources; and, increasingly after around 5000 BC, to locate and exploit metal ores. In China and south-east Asia this becomes intensive after about 3000 BC.’

So if going into a cave was all it took to start a coronavirus pandemic, the odds are it would have happened aeons ago. There are, however, three new reasons that people go into caves today: tourism, collecting bat guano, and science. The abandoned copper mine in Yunnan where the closest relative of Sars-CoV-2 was found is an unnatural, man-made tunnel, not an example of pristine nature. After guano-shovelling -miners got ill there in 2012, the only visitors to the site, as far as we can tell, were scientists, mostly from the Wuhan Institute of Virology more than 1,000 miles away. They not only went into the mine, disturbing the bats; they also captured them in nets, swabbed their rear ends for viruses and took them back to Wuhan labs. Now that’s encroachment.

Share your comments on Matt's Facebook (/authormattridley) and Twitter (@mattwridley) profiles. Stay updated on new content by following him there, and then subscribing to his new newsletter.

Matt's upcoming book with Alina Chan Viral: The Search for the Origin of Covid is now available to pre-order.

How Innovation Works by Matt Ridley is now available in paperback, in the US, Canada, the United Kingdom and elsewhere. The first chapter is available to download for free.

Matt Ridley's Blog

- Matt Ridley's profile

- 2180 followers