Martin Edwards's Blog, page 99

December 27, 2019

Forgotten Book - The Unfinished Crime

[image error]

Why hasn't Elisabeth Sanxay Holding featured more prominently in histories of the genre? It's a mystery in itself. The late Ed Gorman, a very good novelist as well as a considerable authority on crime writing, once commented on this blog about his admiration for her work. And the more of it that I've read, the more I've come to appreciate that he was, as usual, right. So, for that matter, were other Holding fans such as Anthony Boucher and Raymond Chandler.

The Unfinished Crime was one of her earlier crime novels. It appeared in 1934, and my US edition, published by Dodd, Mead, under their Red Badge imprint, has a splendid blurb which says that the story's quality "makes the usual array of fingerprints, weapons, alibis setc, look like claptrap". Talk about not pulling your punches! And surprise, surprise, the promise of the blurb is borne out by the story.

It's a story of suburban life. Andrew Branscombe is a well-off, conventional fellow who is contemplating marriage. He's not old, but he's rather staid and selfish. At first, though, he seems decent enough. However, an encounter with his beloved's estranged husband leads to his committing a crazy act of violence. The rest of the story is about his attempt to escape the consequences of his actions.

Holding's study of criminal psychology is compelling, and she cleverly shows the effect that the crime has on Branscombe's personality, drawing out the darker side that he had kept hidden until now. There's a touch of Francis Iles about it, but really Holding was a distinctive writer who needs to be judged on her own, very considerable merits. Yes, I was impressed by this story.

Published on December 27, 2019 10:57

December 24, 2019

Christmas Greetings!

Christmas is almost here and I'd like to wish each and every reader of this blog a thoroughly enjoyable holiday season - and plenty of good reading to get you through the long winter nights if you're in this part of the world. At least there's no shortage of excellent books to devour...

It's with some astonishment that I find I'm heading towards 3000 posts on this blog - a landmark I should pass in the first half of next year, all being well. Nearly 2.1 million views (wow!) and almost 13,000 comments in that time (not counting those weird spam comments that crop up from time to time and are even more numerous; I delete them constantly and keep wondering what on earth is the point of them.)

Thanks to this blog, I've got to know, sometimes in person (eventually), a great many delightful people. This has been hugely rewarding. What's more, your positive and well-informed reactions to my musings have been a great morale-booster in both difficult times and good times. Speaking of the latter, there's no doubt whatsoever that my life as a crime writer has become even more enjoyable since I started this blog and I'm sure there's a connection.

Anyway, thank you so much for your continued interest. I take nothing for granted about good health and good fortune, but my aim is to keep posting here three times a week (give or take) throughout 2020. There are already plenty of Forgotten Books lined up! And I hope to say more about the art and craft of crime writing next year, spurred on by the anticipated publication in summer of Howdunit.

Anyway, that's for the future. Meanwhile, have a wonderful time!

Published on December 24, 2019 03:29

December 20, 2019

Forgotten Book - Dr Thorndyke Intervenes

A couple of years ago, I was fortunate enough to acquire a copy of Dr Thorndyke Intervenes that was inscribed by the author, R. Austin Freeman. The inscription appealed to me because it is one of those relatively uncommon ones that casts some light on the author's construction of the story. He gave the book to his friend R.F. Jessup and explained that "the notorious Druce case furnished the suggestion" for the main plot strand, adding that another element of the plot derived from "my experiences with a pair of platinum-nosed forceps".

The novel was published in 1933 and is written in Freeman's characteristic leisurely, rather prolix style. But it begins with a vivid and memorable opening scene at Fenchurch Street Station when a man comes to reclaim some left luggage. What is found, however, is a trunk that contains a human head. The man immediately flees the scene, leaving bystanders with an inexplicable conundrum.

In typical Freeman style, the focus soon shifts to another plot strand. A likeable American called Pippet has come to England to pursue an unlikely-seeming claim to an inheritance. He has the misfortune to encounter a wily chap with an even wilier solicitor friend, and is naive enough to be induced to hire the lawyer to progress the claim. But they soon come up against Dr Thorndyke, who has been instructed by a rival claimant.

The plot thickens from there. The interest lies not so much in the machinations which resulted in the discovery of the human head (which involve a bunch of not very interesting villains) as in the neat way in which Freeman dovetails the various plot strands. It's quite a clever story, even if the behaviour of one or two of the characters does test one's suspension of disbelief. And, as is so often the case with Freeman, it has a rather unconventional structure and flavour which compensate for the sometimes portentous prose.

The novel was published in 1933 and is written in Freeman's characteristic leisurely, rather prolix style. But it begins with a vivid and memorable opening scene at Fenchurch Street Station when a man comes to reclaim some left luggage. What is found, however, is a trunk that contains a human head. The man immediately flees the scene, leaving bystanders with an inexplicable conundrum.

In typical Freeman style, the focus soon shifts to another plot strand. A likeable American called Pippet has come to England to pursue an unlikely-seeming claim to an inheritance. He has the misfortune to encounter a wily chap with an even wilier solicitor friend, and is naive enough to be induced to hire the lawyer to progress the claim. But they soon come up against Dr Thorndyke, who has been instructed by a rival claimant.

The plot thickens from there. The interest lies not so much in the machinations which resulted in the discovery of the human head (which involve a bunch of not very interesting villains) as in the neat way in which Freeman dovetails the various plot strands. It's quite a clever story, even if the behaviour of one or two of the characters does test one's suspension of disbelief. And, as is so often the case with Freeman, it has a rather unconventional structure and flavour which compensate for the sometimes portentous prose.

Published on December 20, 2019 08:24

December 19, 2019

Last Minute Christmas Presents?

Bought all your Christmas presents yet? If you're anything like me (though I trust that many of the readers of this blog are a bit better organised!) the answer will be no. So I thought I'd offer a mixed bag of ideas for last minute stocking fillers. These are, for the most part, books I haven't mentioned previously on this blog - though my publishers would shoot me if I didn't point out that Gallows Court is still available on a Kindle monthly deal at an absolutely bargain price!

With novels, of course, one is spoiled for choice. Christine Poulson's An Air That Kills recently received a rave review from Jake Kerridge in the Sunday Express, and is high on my TBR list. During my enjoyable visit to the Isle of Wight for their literary festival, I met James London, and his mystery set on the island (not many crime novels are based there, oddly enough), The Island Murders, offers the opportunity to revisit a very pleasant part of the country. A belated mention too for Mark Brend's Undercliff, an atmospheric read.

Among the big bestsellers, my favourite recent read is Steve Cavanagh's Twisted, which I really enjoyed; it appealed to me even more than his Gold Dagger winning novel The Liar. As regards Lianne Moriarty's megaselling and highly readable Nine Perfect Strangers, it was really the comic lines, some of them very good, that stood out for me ahead of the plot. In contrast, Lucy Foley's The Hunting Party has a plot that twists and turns from the start to finish and although I felt the puzzle element did have a weakness (don't want to give a spoiler, but I wasn't convinced by her account of student life at Oxford) I did find it a gripping story.

For those readers of academic inclination, for a while I've been meaning to mention a couple of definitely niche but interesting textbooks. The Disabled Detective by Susannah B. Mintz is a wide-ranging book, one of the few to discuss John Trench's books (for instance) in any detail. The Bible in Crime Fiction and Drama, edited by Caroline Blyth and Alison Jack boasts an afterword by Liam McIlvanney and is another unexpected but informative book (I certainly didn't expect to come across mention of The Golden Age of Murder in a couple of footnotes!)

And finally, a fun book. I've waxed lyrical about the British Crime Classic often enough and Kate Jackson's Pocket Detective 2 is a follow-up to her previous puzzle book based on the series. If you fancy yourself as a sleuth, you'll find a good deal to enjoy here.

Happy reading!

With novels, of course, one is spoiled for choice. Christine Poulson's An Air That Kills recently received a rave review from Jake Kerridge in the Sunday Express, and is high on my TBR list. During my enjoyable visit to the Isle of Wight for their literary festival, I met James London, and his mystery set on the island (not many crime novels are based there, oddly enough), The Island Murders, offers the opportunity to revisit a very pleasant part of the country. A belated mention too for Mark Brend's Undercliff, an atmospheric read.

Among the big bestsellers, my favourite recent read is Steve Cavanagh's Twisted, which I really enjoyed; it appealed to me even more than his Gold Dagger winning novel The Liar. As regards Lianne Moriarty's megaselling and highly readable Nine Perfect Strangers, it was really the comic lines, some of them very good, that stood out for me ahead of the plot. In contrast, Lucy Foley's The Hunting Party has a plot that twists and turns from the start to finish and although I felt the puzzle element did have a weakness (don't want to give a spoiler, but I wasn't convinced by her account of student life at Oxford) I did find it a gripping story.

For those readers of academic inclination, for a while I've been meaning to mention a couple of definitely niche but interesting textbooks. The Disabled Detective by Susannah B. Mintz is a wide-ranging book, one of the few to discuss John Trench's books (for instance) in any detail. The Bible in Crime Fiction and Drama, edited by Caroline Blyth and Alison Jack boasts an afterword by Liam McIlvanney and is another unexpected but informative book (I certainly didn't expect to come across mention of The Golden Age of Murder in a couple of footnotes!)

And finally, a fun book. I've waxed lyrical about the British Crime Classic often enough and Kate Jackson's Pocket Detective 2 is a follow-up to her previous puzzle book based on the series. If you fancy yourself as a sleuth, you'll find a good deal to enjoy here.

Happy reading!

Published on December 19, 2019 16:15

December 18, 2019

Elaine Viets: guest blog

[image error]

I first met the American crime writer Elaine Viets at Malice Domestic two or three years ago and very much enjoyed chatting to her. Elaine now has a book coming out with Severn House in the UK at the end of this month; it has the rather nice title A Star is Dead and it's the fourth in the Angela Richman Death Investigator series. So what exactly are death investigators? Elaine explains...

"There’s a new crime profession in the US – death investigator – and my Angela Richman series features a working death investigator. A Star Is Dead is set in mythical Chouteau County, a 'ten-square-mile pocket of white privilege' in the Midwest. Angela works for the Chouteau County medical examiner. She investigates all unexpected and unexplained deaths: accidents, murders, suicides. She's responsible for the dead person. The police handle the scene – everything but the body.

To make sure Angela had the most accurate forensics, I took the Medicolegal Death Investigators Training Course at St. Louis University's School of Medicine. Death investigators started in my hometown of St. Louis, Missouri, in 1978 because of a shortage of forensic pathologists. DIs are sort of like forensic paralegals. They are trained, but don't have medical degrees like pathologists. Students came from as far away as Australia for this course. I sat between an Illinois police chief and a working DI from Austin, Texas.

Here's one day's agenda for the death investigator course:In the morning, we learned about gunshot wound fatalities, explosion-related deaths, motor vehicle fatalities and drowning. At lunch we watched a video about teen driving and alcohol that made me want to trade my car for an armored personnel carrier.

Then it was alcohol-related deaths, suicide, blunt-trauma fatalities and more. I was grateful that the airplane crash investigations weren't on the same day I flew home.

For more than eight hours, the death investigator course studied photos and videos from crime scenes and autopsies. I'm sure if I saw – and smelled – real autopsies, I'd be pea green and upchucking. The photos gave enough distance that I could tolerate the gruesome illustrations. By the end of the course, I even watched an autopsy video during lunch.

The course made me a different woman. Not only do I have the latest forensics – I became a temporary vegetarian. It was months before I could eat pasta with red sauce or cut up a chicken. After all, people are a hundred-plus pounds of raw meat.

Oh, and if you have a "Born to Lose" tattoo? That almost guarantees you'll live up that promise. I lost count of how many times I saw that tattoo in autopsy photos. The most dramatic was a man with "Born to Lose" in black Gothic letters on his forehead.

Right under the bullet hole."

[image error]

Published on December 18, 2019 03:30

December 16, 2019

Classic Crime aplenty

It's been another great year for fans of classic crime fiction. Many good books have reappeared after decades out of print and connections between enthusiasts in different parts of the world are becoming ever stronger. A fortnight ago I attended a meeting at the British Library where, among other things, we were discussing titles for the rest of 2020 and into 2021 and I'm happy to report that there are some terrific books lined up. Details to follow before long....

What is more, there is no sign of public appetite for the BL's Crime Classics series starting to diminish. Take, for instance, Mary Kelly's book The Christmas Egg, this year's principal seasonal title (there's also a more orthodox whodunit, Death in Fancy Dress by Anthony Gilbert). It's a rather idiosyncratic story by a writer of distinction and when the book first appeared towards the end of the 50s, it gained respectful reviews but didn't set the world on fire in sales terms. How things change. After just three weeks, the book went into its third reprint, and sales in that time are massive - already far outstripping those of the original. When you think about it, that's really quite remarkable. And some perceptive reviewers have highlighted the book's strengths. I'm particularly glad for Mary's widower, Denis, who has had so much joy from seeing his late wife's reputation as a novelist revived. And there's more to come - her masterpiece, the Gold Dagger-winning The Spoilt Kill, will be published next year.

In the UK, the support of Waterstones has been an invaluable help in ensuring that the series gets plenty of attention. How many other UK publishers have, like the BL, their own dedicated table in Waterstones' branches? When I popped in to Waterstone's Piccadilly branch recently I was thrilled to see the piles of classic mysteries on a very large table indeed. And yes, I can't deny that I relished seeing many copies of my own anthologies there too.

Other publishers are doing their bit. HarperCollins' Detective Story Club series is taking a sabbatical, but my understanding is that HarperCollins will soon be bringing out new paperback editions of several good titles by Freeman Wills Crofts that have long been unavailable. And hats off to Dean Street Press, who continue to produce large numbers of reprints in ebook or print on demand paperback format.

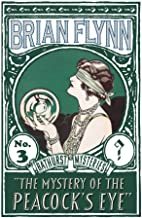

Among the Dean Street Press books, I'd particularly like to highlight two series. The first is the set of books by Brian Flynn, the second is those by E. and M.A. Radford. They benefit from excellent introductions by two fans who have done a good deal of admirable work in the field. Steve Barge (who blogs as The Puzzle Doctor) is a passionate Flynn fan, while Nigel Moss has long admired the work of the Radfords. I haven't yet read enough of either novelist to be able to judge them for myself (where does the time go?), but the enthusiasm of Steve and Nigel is a recommendation in itself.

Published on December 16, 2019 09:07

December 13, 2019

Forgotten Book - Appointment with Yesterday

Celia Fremlin was a remarkable woman, and a remarkable writer. I had the pleasure to meet her briefly in the early 1990s, at a CWA conference, although I didn't have the chance to talk to her at great length. I've admired her writing for a long time, though I haven't read all her books by any means, and I've only recently caught up with her 1972 mystery Appointment with Yesterday.

This is a really terrific novel. It's a story of domestic suspense, but it's the wittiest example of that sub-genre that I can recall having read. There are many acute insights and touches of humour, which relieve a rather dark storyline, and make the whole book entertaining as well as perceptive. It's at least as good as her excellent debut, The Hours Before Dawn, which won an Edgar.

This is the story of a woman who calls herself Milly Barnes. We know that isn't her real name, and we also know that she is on the run, fleeing from something terrible. What has she done, why is she so afraid? Milly can be exasperating, and can seem weak and rather stupid, but gradually Fremlin reveals the circumstances that have shaped her personality, and our sympathy for her grows.

Milly runs off to a seaside town where she takes a number of part-time jobs as a cleaner. Fremlin herself had worked in domestic service, and her presentation of the relations between employer and employed is as enjoyable as it is plausible. Meanwhile, the tension mounts, since someone is trying to find Milly. Who can it be, and what do they want? I can strongly recommend this excellent novel. It deserves to be much better-known.

This is a really terrific novel. It's a story of domestic suspense, but it's the wittiest example of that sub-genre that I can recall having read. There are many acute insights and touches of humour, which relieve a rather dark storyline, and make the whole book entertaining as well as perceptive. It's at least as good as her excellent debut, The Hours Before Dawn, which won an Edgar.

This is the story of a woman who calls herself Milly Barnes. We know that isn't her real name, and we also know that she is on the run, fleeing from something terrible. What has she done, why is she so afraid? Milly can be exasperating, and can seem weak and rather stupid, but gradually Fremlin reveals the circumstances that have shaped her personality, and our sympathy for her grows.

Milly runs off to a seaside town where she takes a number of part-time jobs as a cleaner. Fremlin herself had worked in domestic service, and her presentation of the relations between employer and employed is as enjoyable as it is plausible. Meanwhile, the tension mounts, since someone is trying to find Milly. Who can it be, and what do they want? I can strongly recommend this excellent novel. It deserves to be much better-known.

Published on December 13, 2019 14:37

December 11, 2019

The House on the Cliff - a play

I've mentioned previously that the local amateur dramatic society here, the long-established Bridgewater Players, occasionally perform entertaining whodunits at Thelwall Parish Hall, not far from where I live. Through one of their earlier shows, I got to know the playwright Derek Webb, and I recently attended their latest production, The House on the Cliff, by George Batson.

I was particularly intrigued by the title, given that Mortmain Hall, due to be published in April next year, involves - well, a house on a cliff. Suffice to say that the two storylines have nothing else in common - phew! The play concerns Ellen, a young heiress (daughter of a deceased lawyer) who is confined to a wheelchair, although her doctor believes there's nothing really wrong with her. She is looked after by her father's second wife and a housekeeper. When the doctor has to go to France, he calls in a nurse and a second doctor to look after her.

There is an odd aspect of the plot of the play which didn't seem to make sense in legal terms - it concerns the late lawyer's will. And I wasn't the only person to spot the anomaly. The explanation, I suspect, comes from the fact that the play was written by an American and originally set in the US, where the law is different. The action of the version I watched has been transposed to the UK, with the house relocated to a cliff in Kent, overlooking the English Channel. However, whoever amended the script (many years ago, I suspect) would have done better to correct the error - it could have been done quite easily.

I'd never heard of George Batson (1918-77), but Amnon Kabatchnik's invaluable Blood on the Stage reveals that he wrote nine plays, including one called Ramshackle Inn (1944) which enjoyed poor reviews but a good run. Kabatchnik reckons that The House on the Cliff is his most intriguing work, and I certainly enjoyed the performance by the Bridgewater Players. The challenging role of Ellen was particularly well-handled by Maria Marano, while Deborah Harper was a suitably equivocal stepmother and Cat Mercer a breezy nurse. Groups such as the Bridgewater Players deserve a good deal of support, and the first two nights of the three-night run were sold out. I managed to get tickets for the Saturday performance simply because it clashed with Strictly Come Dancing! I was glad I watched the play instead...

I was particularly intrigued by the title, given that Mortmain Hall, due to be published in April next year, involves - well, a house on a cliff. Suffice to say that the two storylines have nothing else in common - phew! The play concerns Ellen, a young heiress (daughter of a deceased lawyer) who is confined to a wheelchair, although her doctor believes there's nothing really wrong with her. She is looked after by her father's second wife and a housekeeper. When the doctor has to go to France, he calls in a nurse and a second doctor to look after her.

There is an odd aspect of the plot of the play which didn't seem to make sense in legal terms - it concerns the late lawyer's will. And I wasn't the only person to spot the anomaly. The explanation, I suspect, comes from the fact that the play was written by an American and originally set in the US, where the law is different. The action of the version I watched has been transposed to the UK, with the house relocated to a cliff in Kent, overlooking the English Channel. However, whoever amended the script (many years ago, I suspect) would have done better to correct the error - it could have been done quite easily.

I'd never heard of George Batson (1918-77), but Amnon Kabatchnik's invaluable Blood on the Stage reveals that he wrote nine plays, including one called Ramshackle Inn (1944) which enjoyed poor reviews but a good run. Kabatchnik reckons that The House on the Cliff is his most intriguing work, and I certainly enjoyed the performance by the Bridgewater Players. The challenging role of Ellen was particularly well-handled by Maria Marano, while Deborah Harper was a suitably equivocal stepmother and Cat Mercer a breezy nurse. Groups such as the Bridgewater Players deserve a good deal of support, and the first two nights of the three-night run were sold out. I managed to get tickets for the Saturday performance simply because it clashed with Strictly Come Dancing! I was glad I watched the play instead...

Published on December 11, 2019 04:15

December 9, 2019

Elizabeth is Missing - BBC TV review

As soon as I heard that Glenda Jackson was going to play the lead role in the BBC TV version of Emma Healey's brilliant novel Elizabeth is Missing, I felt sure that it was the most perfect piece of casting. And so it proved. Jackson was fantastic as Maud, the elderly woman with dementia who becomes obsessed about the disappearance of her best friend. She's convinced something bad has happened to Elizabeth, but nobody believes her.

The past becomes intertwined with the present, and the screenplay by Andrea Gibb impressed me, even though some important aspects of Healey's storyline were lost. This was a necessary sacrifice because the TV version ran only for 90 minutes, and on the whole this made a refreshing change from the present day pattern of storylines stretched out interminably beyond their natural length in order to make a six or eight part series (I've seen several of these this year and have mostly not bothered to review them, because the format makes one lose the will to live).

No such danger here. When I reviewed the book here back in

The whodunit plot seems, at times, almost incidental, but it isn't really. The outcome of the story is a triumphant vindication of Maud and her persistence, and even if it's inevitable that her memory will continue to deteriorate, it is - as far as it can be - a happy ending. But a realistic one. A television triumph.

Published on December 09, 2019 02:13

December 7, 2019

Christmas Mysteries: guest post from Nigel Bird

[image error]

Nigel Bird has a new novel coming out called Let it Snow, published by Down and Out Books. As you might imagine, the storyline has a seasonal theme. So I invited him to write a guest post, musing on the appeal of Christmas mysteries. Over to you, Nigel:

"Why are so many crime novels set over Christmas?I began by wearing my cynical hat. Everyone’s out there buying presents at this time of year and people love receiving books as gifts. Pair the two and perhaps it’s the kerching of the cash tills that tempts publishers and authors to set work over the festive period. But that seems harsh. I’d prefer to think that their motivation is less the cold drive of economic reality than that they want plenty of angels to get their wings as registers ring. And if you think about it, writing a story set at such a specific time of year might actually be detrimental to a book’s success. Sure, crime fans will want to read murder mysteries set over Christmas as they build up to the holiday and while they wind down afterwards, but do they really want to be doing that very same thing in the height of summer? Or during the rebirth of spring? Or on a crisp autumnal evening? I’m not convinced. If the financial reason is eliminated then what else does Christmas offer to the crime novel? For starters, Christmas can be murder. And what else comes to mind? Time pressures for one. The need to buy gifts before the 25th, to ensure the drinks cabinet is full and to get the food cooked and plated while it’s all still piping hot. They’re mirrored by the pressing need to solve a case before the serial killer takes out another victim or the kidnapper who has set a deadline that has police racing the clock. Between the crimes and the domestic pressure there’s plenty of conflict to drive a story forward and maintain levels of tension. And then there’s the natural environment. It’s the bleak mid-winter. There can be snow, hail, rain, ice or fog. The days are short and the nights long. The criminal has plenty of natural cover to work with. Add to that the boozy chaos of revellers that December brings. Wild office parties that so easily descend into chaos, tempting folk let their hair down until they’re doing impressions of Rapunzel without caring too much who is climbing their way to the top. Anything can happen and, in the hands of the right imagination, probably will. Into the mix, we can throw in the element of disguise. What better way to blend in with the background than to wear a red suit and black gloves with a beard of cotton wool? Not to mention the empty sack to gather all the swag the average thief can carry. I suspect that the nature of Santa Claus was less defined by Coca Cola than by some criminal mastermind with a wonderfully twisted sense of humour.To help the writer further, the Christmas period spans three days, each with their own identity and traditions. That’s plenty of time to settle many a mystery and if that’s not enough, things can be easily stretched into the New Year and all the madness that brings. I can imagine you’re coming up with lots of reasons of your own. How December becomes an easy backdrop: Christmas trees, gardens lit up like Vegas, crowds with plenty of pockets to be picked and bags to be snatched. We have carol singers, shoplifting, fraud, holiday traffic, empty houses, piles of presents in full view to passers-by, stray kisses under the mistletoe, over-indulgence, hangovers and the ghosts of Christmas past. There might even be something deadly baked into that pudding, so let’s be careful out there..."

Published on December 07, 2019 04:01