Martin Edwards's Blog, page 87

August 28, 2020

Forgotten Book - A Dandy in Aspic

All too frequently, I find I need a nudge to get round to doing something I meant to do ages ago. And this is sometimes true as regards reading books as well as less pleasurable tasks. Take Derek Marlowe's A Dandy in Aspic, for instance. I first read about this one many years ago, in Julian Symons' Bloody Murder. I thought it sounded interesting, especially given that he compared it to Kenneth Fearing's The Big Clock, but somehow I never made much of an effort to track the book down.

The nudge I needed came when Joseph Goodrich asked me to read the manuscript of his book Unusual Suspects with a view to providing an introduction. Joe is an interesting and versatile writer and I was glad to agree. What I didn't expect was that his book would include a long piece about Derek Marlowe's life and career. This was quite fascinating and I went straight out and picked up a paperback of A Dandy in Aspic.

I'm glad I did. This is in some ways a flawed book, but the central idea is appealing, and the execution is, for the most part, highly entertaining. Our narrator is a chap called Eberlin. He works for the government, but it soon become apparent that he is a Soviet agent. Not only that, he is a hitman. The British secret service are concerned that some of their agents are being eliminated. So who better to hunt down the assassin? Eberlin, naturally...

The mannered style of writing is occasionally irritating, but on the whole adds to the enjoyment. My copy describes the book modestly as "the most brilliant spy novel of the decade". Wow! Given that Fleming, Le Carre, and Deighton were hard at work in the 60s, this is the wildest of hype. But the novel was filmed, with Laurence Harvey and Mia Farrow, and my next objective is to watch the movie version. I'm glad I finally read the story, and my thanks go to Joe Goodrich for giving me that all-important nudge.

The nudge I needed came when Joseph Goodrich asked me to read the manuscript of his book Unusual Suspects with a view to providing an introduction. Joe is an interesting and versatile writer and I was glad to agree. What I didn't expect was that his book would include a long piece about Derek Marlowe's life and career. This was quite fascinating and I went straight out and picked up a paperback of A Dandy in Aspic.

I'm glad I did. This is in some ways a flawed book, but the central idea is appealing, and the execution is, for the most part, highly entertaining. Our narrator is a chap called Eberlin. He works for the government, but it soon become apparent that he is a Soviet agent. Not only that, he is a hitman. The British secret service are concerned that some of their agents are being eliminated. So who better to hunt down the assassin? Eberlin, naturally...

The mannered style of writing is occasionally irritating, but on the whole adds to the enjoyment. My copy describes the book modestly as "the most brilliant spy novel of the decade". Wow! Given that Fleming, Le Carre, and Deighton were hard at work in the 60s, this is the wildest of hype. But the novel was filmed, with Laurence Harvey and Mia Farrow, and my next objective is to watch the movie version. I'm glad I finally read the story, and my thanks go to Joe Goodrich for giving me that all-important nudge.

Published on August 28, 2020 15:39

Forgotten Book - These Names Make Clues

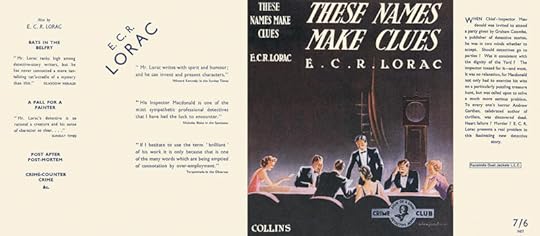

Earlier this year, I was fortunate enough to lay my hands on an inscribed copy of E.C.R. Lorac's These Names Make Clues, an uncommon Collins Crime Club title from 1937; no dust jacket (the one in pictured is an image from Mark Terry's fascinating site of facsimile wrappers), but still a treasured possession. All the more so because the story is an enjoyable one. In fact I'd rate this as one of the more interesting Loracs.

A key reason for my enthusiasm is that this book is more in the realm of the classic "closed circle" puzzle mystery than some of the author's other work. Inspector Macdonald is invited to a Treasure Hunt evening convened by a publisher called Graham Coombe, who shares a big house in London with his sister Susan. His fellow guests are mystery writers, but part of the fun is for their identities to be concealed under pseudonyms.

The seasoned crime fan won't be surprised to learn that this pleasant idea backfires when a death takes place during the treasure hunt. The deceased was an author called Andrew Gardien, and the suspects are the Coombes and the novelists. Complications ensue when Gardien's literary agent is also found dead. Were either of the deaths murder? Macdonald investigates, abetted by a breezy young journalist called Vernon.

What fascinates me particularly about this novel, published in the year that Lorac was elected to membership of the Detection Club, is that there are strong reasons to infer that her initial experience of the Club supplied the inspiration for the story and some of the characters. Coombe may be Billy Collins, but I'm fairly sure that Gardien was inspired (albeit not in terms of his personality) by John Rhode.

I also suspect that Rhode influenced (maybe even suggested to her; he was a generous man) Lorac's choice of m.o. in relation to the two deaths. Other characters seem to me to bear traces of Douglas and Margaret Cole, and Baroness Orczy. As for the plot, it boasts variety and ingenious touches aplenty, though to my mind it's not really a "fair play" whodunit, given that a key fact is revealed rather late on. Definitely a book that deserves better than the obscurity which has been its fate since the 1930s.

Published on August 28, 2020 04:54

August 26, 2020

Another Life - 2001 film review

Another Life is a film that is surprisingly little-known. Dating from 2001 and written and directed by Philip Goodhew, it tells a famous story, that of Edith Thompson, the so-called "Messalina of the Suburbs" who was hanged for a murder committed by her lover Frederick Bywaters. Bywaters attacked Edith's husband Percy late one night. Edith's fate was sealed by compromising letters she'd written to her lover in which she'd fantasised about killing Percy.

The case attracted huge public interest. E.M. Delafield wrote the first novel about it and F.Tennyson Jesse wrote the most acclaimed one, A Pin to See the Peep-Show. The trial fascinated Anthony Berkeley, who took the view that Edith was "executed for adultery"; many commentators agree with his interpretation of events, and the case has gone down in history as a classic miscarriage of justice.

The film pays very little attention to the trial, focusing instead on the story of Edith's life, from the time she first got to know strait-laced Percy. The relationship is nicely drawn, and I was impressed by the lead actors. Natasha Little (Edith), Nick Moran (Percy), and Ioan Gruffud (Freddie) are all perfectly convincing, though my previous impression had been that Freddie was rather more stupid than his portrayal here suggests. Ioan Gruffud presents him as passionate and volatile, and it's certainly a credible reading of the character. Rachael Stirling is also very good as Edith's sister Avis.

I've read and written about this case a number of times, and I was pleased by the way the film made me think about it afresh in some respects. To what extent did Edith really want her husband to die? What was in Bywaters' mind when he launched his murderous attack? Did he genuinely expect to get away with it? Philip Goodhew doesn't try to give definitive answers to these questions. but his film is highly watchable.

The case attracted huge public interest. E.M. Delafield wrote the first novel about it and F.Tennyson Jesse wrote the most acclaimed one, A Pin to See the Peep-Show. The trial fascinated Anthony Berkeley, who took the view that Edith was "executed for adultery"; many commentators agree with his interpretation of events, and the case has gone down in history as a classic miscarriage of justice.

The film pays very little attention to the trial, focusing instead on the story of Edith's life, from the time she first got to know strait-laced Percy. The relationship is nicely drawn, and I was impressed by the lead actors. Natasha Little (Edith), Nick Moran (Percy), and Ioan Gruffud (Freddie) are all perfectly convincing, though my previous impression had been that Freddie was rather more stupid than his portrayal here suggests. Ioan Gruffud presents him as passionate and volatile, and it's certainly a credible reading of the character. Rachael Stirling is also very good as Edith's sister Avis.

I've read and written about this case a number of times, and I was pleased by the way the film made me think about it afresh in some respects. To what extent did Edith really want her husband to die? What was in Bywaters' mind when he launched his murderous attack? Did he genuinely expect to get away with it? Philip Goodhew doesn't try to give definitive answers to these questions. but his film is highly watchable.

Published on August 26, 2020 14:45

August 24, 2020

Events of a new kind

We all know that lockdown has been nightmarish for many people and organisations, including those trying to organise events and festivals. But these strange times have brought out the best in many of them. There's been a great deal of innovative thinking, and much hard work has gone in to trying to connect readers and writers.

Podcasts have been gaining rapidly in popularity and Shedunnit is a very good example. Run by Caroline Crampton, it's a good example of the marriage of enthusiasm, expertise, and enterprise. I was glad to accept her invitation to talk about the Detection Club recently, and the result has just been aired: https://shedunnitshow.com/detectionclub/

Last week I was busy recording two videos which will be released later. I must say that I much prefer pre-recorded videos to live ones, even though the 'live' element can have real benefits. The difficulty is that, if you have four or five people taking part in a live video event, there is every chance of a technological glitch, and although these can never be ruled out, I think that - where possible - it's less stressful to pre-record, and allow for editing.

There was a bittersweet aspect to the first video. Last year I was invited to the Sacramento Bouchercon to interview Anthony Horowitz, and I was very much looking forward to the trip for a host of reasons. Alas, it was not to be. Undaunted, the organisers set up a recorded video; I was based in England, while Anthony was speaking from Crete. It was fun to do, and will be made available in October, to coincide with the period when Bouchercon would have been taking place.

The second video was part of Slaughterfest, set up by HarperCollins to celebrate Karin Slaughter's work. I was honoured to be asked to chair a panel to discuss classic crime fiction. The panelists were four bestselling novelists, Lucy Foley, Kate Weinberg, Sophie Hannah, and Ruth Ware, and the conversation proved very enjoyable. Again, the discussion was pre-recorded, and it will be made available soon.

I'm now in discussions about various other virtual events. A couple of these will involved conversations with Ann Cleeves, while others will focus more generally on crime fiction past and present. To say that I'm grateful to those who do the hard work of making these events happen is an under-statement.

Podcasts have been gaining rapidly in popularity and Shedunnit is a very good example. Run by Caroline Crampton, it's a good example of the marriage of enthusiasm, expertise, and enterprise. I was glad to accept her invitation to talk about the Detection Club recently, and the result has just been aired: https://shedunnitshow.com/detectionclub/

Last week I was busy recording two videos which will be released later. I must say that I much prefer pre-recorded videos to live ones, even though the 'live' element can have real benefits. The difficulty is that, if you have four or five people taking part in a live video event, there is every chance of a technological glitch, and although these can never be ruled out, I think that - where possible - it's less stressful to pre-record, and allow for editing.

There was a bittersweet aspect to the first video. Last year I was invited to the Sacramento Bouchercon to interview Anthony Horowitz, and I was very much looking forward to the trip for a host of reasons. Alas, it was not to be. Undaunted, the organisers set up a recorded video; I was based in England, while Anthony was speaking from Crete. It was fun to do, and will be made available in October, to coincide with the period when Bouchercon would have been taking place.

The second video was part of Slaughterfest, set up by HarperCollins to celebrate Karin Slaughter's work. I was honoured to be asked to chair a panel to discuss classic crime fiction. The panelists were four bestselling novelists, Lucy Foley, Kate Weinberg, Sophie Hannah, and Ruth Ware, and the conversation proved very enjoyable. Again, the discussion was pre-recorded, and it will be made available soon.

I'm now in discussions about various other virtual events. A couple of these will involved conversations with Ann Cleeves, while others will focus more generally on crime fiction past and present. To say that I'm grateful to those who do the hard work of making these events happen is an under-statement.

Published on August 24, 2020 05:42

August 21, 2020

Forgotten Book - The Case of the Four Friends

J. C. Masterman was a man of many parts. An eminent figure who rose to become Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University, Sir John Cecil Masterman was an academic and also a key figure in British espionage during the war, overseeing the organisation of double agents. As if that wasn't enough, he wrote a notable detective novel, An Oxford Tragedy; it wasn't the very first Oxford-based crime story, but its success set the ball rolling and of course it has had innumerable successors.

It was on the strength of that book, above all, that he was elected to membership of the Detection Club. Many moons ago, I wrote a short article about Masterman for CADS, which was later adapted for the website Tangled Web UK, in its hey-day the go-to place on the internet for information about crime fiction. I'm sorry to see that the site has now vanished, but Geoff Lees and his family did a great service for many writers, publicising their books on the site over many years. Thank goodness CADS is still going strong.

The novel featured a Viennese professor, Ernest Brendel, and after the war, no doubt much encouraged by his admirers, Masterman revived Brendel, and brought him back to Oxford for another detective story. This was The Case of the Four Friends, published in 1957, almost a quarter of a century after its predecessor.

The story has a very clever premise, a sort of refined version of the "whowasdunin". Brendel tells a story about four people ("friends" is stretching it a bit) which is an exercise in pre-detection: can he prevent a murder from taking place? And the reader has to figure out both the prospective murderer and the prospective victim.

Unfortunately, the story is lacking in action and there's no attempt to make use of the Oxford setting - the story might have been recounted anywhere. I think the idea could have been livened up, and it's a pity Masterman didn't do this. Instead, we get a rather dry, cerebral tale. But for its inherent ingenuity, if not its execution, it earns high marks

It was on the strength of that book, above all, that he was elected to membership of the Detection Club. Many moons ago, I wrote a short article about Masterman for CADS, which was later adapted for the website Tangled Web UK, in its hey-day the go-to place on the internet for information about crime fiction. I'm sorry to see that the site has now vanished, but Geoff Lees and his family did a great service for many writers, publicising their books on the site over many years. Thank goodness CADS is still going strong.

The novel featured a Viennese professor, Ernest Brendel, and after the war, no doubt much encouraged by his admirers, Masterman revived Brendel, and brought him back to Oxford for another detective story. This was The Case of the Four Friends, published in 1957, almost a quarter of a century after its predecessor.

The story has a very clever premise, a sort of refined version of the "whowasdunin". Brendel tells a story about four people ("friends" is stretching it a bit) which is an exercise in pre-detection: can he prevent a murder from taking place? And the reader has to figure out both the prospective murderer and the prospective victim.

Unfortunately, the story is lacking in action and there's no attempt to make use of the Oxford setting - the story might have been recounted anywhere. I think the idea could have been livened up, and it's a pity Masterman didn't do this. Instead, we get a rather dry, cerebral tale. But for its inherent ingenuity, if not its execution, it earns high marks

Published on August 21, 2020 10:19

August 19, 2020

The Incident - 2015 film review

The Incident (the 2015 film of that name) is described on Amazon Prime as a 'powerful, emotionally haunting modern British noir'. For me, the key adjective is 'under-stated'. In fact, to call it 'under-stated' is itself an under-statement. The storyline is clear and coherent, but minimalist to say the least. Writer-director Jane Linfoot certainly didn't go over the top. If anything, she aimed too low.

Joe and Annabel are a young married couple who seem to have it all. They are rich, successful, and ridiculously good-looking. And Annabel's about to get pregnant. What could possibly go wrong? Well, Joe being talked into an unspecified sexual encounter by a young girl while he waits for a takeaway pizza, that's what. It's the incident that dictates the rest of the film.

I imagined all kinds of dramatic developments that might flow from Joe's unhappy misjudgement. But Linfoot doesn't go in for melodrama. Instead, she opts for a character study focusing mainly on the rich couple. The girl is presented as a caged bird, someone trapped in a miserable lifestyle, but this isn't really explored. Nor are the characters of Joe and Annabel, who - it must be said - are by no means endearing. Wealth and good looks don't equate to happiness seems to be the simple moral.

Ruth Gedmintas, Tom Hughes, and Tasha Connor perform capably in rather two-dimensional roles, with Gedmintas particularly good. The failure of the story to catch fire frustrated me, but I must say that I did keep watching, and I think that Linfoot deserves credit for making a film that is consistently engaging, despite failing to deliver on its full potential. The script and characters are under-written, but even though this is a slight film, it is well-made and certainly watchable.

Joe and Annabel are a young married couple who seem to have it all. They are rich, successful, and ridiculously good-looking. And Annabel's about to get pregnant. What could possibly go wrong? Well, Joe being talked into an unspecified sexual encounter by a young girl while he waits for a takeaway pizza, that's what. It's the incident that dictates the rest of the film.

I imagined all kinds of dramatic developments that might flow from Joe's unhappy misjudgement. But Linfoot doesn't go in for melodrama. Instead, she opts for a character study focusing mainly on the rich couple. The girl is presented as a caged bird, someone trapped in a miserable lifestyle, but this isn't really explored. Nor are the characters of Joe and Annabel, who - it must be said - are by no means endearing. Wealth and good looks don't equate to happiness seems to be the simple moral.

Ruth Gedmintas, Tom Hughes, and Tasha Connor perform capably in rather two-dimensional roles, with Gedmintas particularly good. The failure of the story to catch fire frustrated me, but I must say that I did keep watching, and I think that Linfoot deserves credit for making a film that is consistently engaging, despite failing to deliver on its full potential. The script and characters are under-written, but even though this is a slight film, it is well-made and certainly watchable.

Published on August 19, 2020 04:30

August 17, 2020

Match Point - 2005 film review

Match Point is a film from fifteen years ago, written and directed by Woody Allen. Apparently he originally intended to set the story in the US, but funding issues prompted him to come to Britain. The result is a film that seems to me to be rather untypical of his work, but not wholly unrecognisable. There are touches of Dostoevsky and Dreiser, yes, but also a hint of Ruth Rendell. For this film is a psychological thriller, although its true nature isn't apparent until the later stages of the story.

Jonathan Rhys Meyers is Chris Wilton, a charismatic former tennis player, who at the start of the film introduces us to the central theme of the film. It's about luck - does the tennis ball that touches the net drop on the right side or not? The script (which was nominated for an Oscar) plays with this notion rather cleverly. Chris becomes friendly with Tom Hewett (Matthew Goode, very smooth) and is introduced to his very wealthy family. Tom's Dad (Brian Cox in benevolent mood) is a rich tycoon, his mother (Penelope Wilton) is a charming meddler and his sister Chloe (Emily Mortimer) is instantly smitten with Chris.

The snag is that, once Chris meets Tom's fiancee, he is smitten with her. Scarlett Johansson plays Nola Rice, a glamorous American actress. She and Chris have a fling, but Chris marries Chloe and Tom splits up with Nola. Trouble is, Chris subsequently bumps into Nola and the affair resumes. You just know that it isn't going to end well. And for some of the characters, it doesn't.

The lead actors are terrific, and the impressive supporting cast includes Margaret Tyzack, James Nesbitt, Mark Gatiss, John Fortune, Steve Pemberton, and Alexander Armstrong. It's a long film, but it doesn't really sag prior to the dramatic events of the last twenty minutes. The characters may not be loveable, but they are interesting, and cleverly presented so that their unappealing attitudes aren't as much of a turn-off as perhaps they ought to be. Overall, a very enjoyable film.

Jonathan Rhys Meyers is Chris Wilton, a charismatic former tennis player, who at the start of the film introduces us to the central theme of the film. It's about luck - does the tennis ball that touches the net drop on the right side or not? The script (which was nominated for an Oscar) plays with this notion rather cleverly. Chris becomes friendly with Tom Hewett (Matthew Goode, very smooth) and is introduced to his very wealthy family. Tom's Dad (Brian Cox in benevolent mood) is a rich tycoon, his mother (Penelope Wilton) is a charming meddler and his sister Chloe (Emily Mortimer) is instantly smitten with Chris.

The snag is that, once Chris meets Tom's fiancee, he is smitten with her. Scarlett Johansson plays Nola Rice, a glamorous American actress. She and Chris have a fling, but Chris marries Chloe and Tom splits up with Nola. Trouble is, Chris subsequently bumps into Nola and the affair resumes. You just know that it isn't going to end well. And for some of the characters, it doesn't.

The lead actors are terrific, and the impressive supporting cast includes Margaret Tyzack, James Nesbitt, Mark Gatiss, John Fortune, Steve Pemberton, and Alexander Armstrong. It's a long film, but it doesn't really sag prior to the dramatic events of the last twenty minutes. The characters may not be loveable, but they are interesting, and cleverly presented so that their unappealing attitudes aren't as much of a turn-off as perhaps they ought to be. Overall, a very enjoyable film.

Published on August 17, 2020 08:22

Southern Cross Crime by Craig Sisterston

[image error]

I've never had the chance to visit Australia or New Zealand, and the way things are going it's clear that I won't be repairing that omission any time soon. But at least it's possible to travel there through the medium of fiction, and there are plenty of good antipodean crime novels, old and new, to keep one company.

Craig Sisterson's new book Southern Cross Crime, published by Oldcastle Books, is a survey of relatively recent Australian and New Zealand crime and thriller writing. There are brief mentions of some writers of the past such as Arthur Upfield, Ngaio Marsh, and Charlotte Jay, but some other capable writers, such as Pat Flower and S.H. Courtier, don't get a mention, because the focus is on more recent work which tends to be more readily available.

Craig is a knowledgeable commentator on crime fiction, and he and I were part of a quiz team at Harrogate last year on an enjoyable evening, the sort of memory I cherish all the more right now, given the cancellation of so many crime festivals. Although he currently lives in London, he comes from New Zealand and has a good deal of insight into his subject.

The book has a foreword by that estimable author Michael Robotham and is divided into three sections. The longest is a detailed account of antipodean novels and authors by region. The second segment covers TV and film from the past quarter-century. The third is a series of short essays about particular writers, including Peter Corris, Jane Harper, Peter Temple, and Stella Duffy. There is also a useful appendix covering various award winners.

This is a good book to dip into and to keep handy for reference. Thanks to Craig Sisterson's persuasive advocacy, there are a number of authors I'm now keen to read for the first time; he's also managed to reinforce my enthusiasm for several others. Among many lines that caught my eye, I was tempted by 'an amateur sleuth who is also a professional cricketer', namely Mario Shaw, the creation of Carolyn Morwood, a name previously unknown to me. There are plenty of other intriguing references that will encourage readers to add to their TBR piles. This is definitely a useful addition to the crime fan's bookshelf.

Published on August 17, 2020 06:11

August 14, 2020

Forgotten Book - The Unsuspected

I've mentioned Charlotte Armstrong before on this blog. She was a high calibre American writer of domestic suspense. The Unsuspected is highly regarded among her books, and has been reprinted in recent times as part of the revival of interest in crime fiction from the past. So I was delighted to pick up a copy of the novel, which first appeared in book form in 1946, having been serialised the previous year in the Saturday Evening Post.

It's sometimes described as an inverted mystery, but it doesn't follow the usual inverted pattern. Right from the start, we learn that Luther Grandison, a successful stage and film director, is a murderer. He thinks he's unsuspected, but he's wrong. Young Francis Wright and his aunt Jane Moynihan suspect that he's a sociopath responsible for the hanging (supposedly a suicide) of his secretary Rosaleen Wright.

They hatch a plan to infiltrate Grandison's household in order to prove his guilt. This involves Jane working for Grandison and Francis pretending to have married Grandison's ward, who has recently disappeared and been presumed drowned. The snag is that the dead lady turns up out of the blue...

My problem with the story is that the scheme to unmask Grandison seemed to me to be totally hare-brained. Provided one can accept the premise, it's an entertaining enough mystery, with an excellent climactic scene, and I'm not surprised that the book was made into a film, which starred Claude Rains and is sure to be worth watching. But I'm afraid it didn't live up to my expectations, not least because there is little effort to characterise Grandison. He's rather a two-dimensional baddie; Armstrong's real focus is on the young people he torments.

It's sometimes described as an inverted mystery, but it doesn't follow the usual inverted pattern. Right from the start, we learn that Luther Grandison, a successful stage and film director, is a murderer. He thinks he's unsuspected, but he's wrong. Young Francis Wright and his aunt Jane Moynihan suspect that he's a sociopath responsible for the hanging (supposedly a suicide) of his secretary Rosaleen Wright.

They hatch a plan to infiltrate Grandison's household in order to prove his guilt. This involves Jane working for Grandison and Francis pretending to have married Grandison's ward, who has recently disappeared and been presumed drowned. The snag is that the dead lady turns up out of the blue...

My problem with the story is that the scheme to unmask Grandison seemed to me to be totally hare-brained. Provided one can accept the premise, it's an entertaining enough mystery, with an excellent climactic scene, and I'm not surprised that the book was made into a film, which starred Claude Rains and is sure to be worth watching. But I'm afraid it didn't live up to my expectations, not least because there is little effort to characterise Grandison. He's rather a two-dimensional baddie; Armstrong's real focus is on the young people he torments.

Published on August 14, 2020 03:59

August 12, 2020

Bognor is Back

[image error]

I never got to see Bognor when it was first shown on television. It ran for 21 episodes from 1981-2 at a time when I wasn't watching much if any TV. Years later, I had the pleasure of meeting Tim Heald, author of the books on which the show was based, and asked him about it. To cut a long story short, he felt that Thames TV had made a bit of a mess of it. For instance, he'd very much favoured Derek Fowlds being cast in the lead as Simon Bognor, but in the end the role went to David Horovitch, a decent actor but perhaps not ideal for the part. They also put the shows out at times which were unlikely to attract a big audience.

Thanks to Talking Pictures TV, it's now possible to judge Bognor for myself. This channel has a real knack of finding lost gems, as well as some shows and films that haven't really stood the test of time. They have run Public Eye, the downbeat series about the private eye Frank Marker, which was very low-key but pretty good, and the obscure but rather enjoyable anthology series Shadows of Fear as well as the original Van der Valk, which I found surprisingly disappointing.

Bognor comprised the adaptations of four books, starting with Unbecoming Habits, set in a monastery, with one of the monks played by Patrick Troughton. Bognor, who works for the Department of Trade, is sent to investigate a suspicious death. There are some pleasing moments in the story, but overall it's pretty lightweight and forgettable. Apparently the series was cancelled long before it came to an end, and in all honesty, I can see why.

I'm glad to have caught up with it, though. Tim was as amusing in person as he was on the page, and although he took the disappointment of the adaptations in his stride, his enthusiasm for writing about the character waned. I encouraged him to consider reviving Simon Bognor after a long hiatus, and he duly contributed a fresh Bognor short story to an anthology I edited for the CWA, Original Sins. Before long, he was working on a new Bognor novel. Thanks to Bognor, I've thought back to those times (too few, alas) that I spent in his convivial company, and those pleasant memories are enough to keep me watching, even if the scripts don't quite do the trick.

Published on August 12, 2020 10:40