Martin Edwards's Blog, page 79

February 17, 2021

Ellery Queen: Don't Look Behind You

In the very early days of this blog, I mentioned the TV series featuring Jim Hutton as Ellery Queen. I acquired the shows as a box set and have watched one or two episodes. The series was created by William Link and Richard Levinson, prolific writers who are probably best known for Columbo. One TV film for which they are not so well-known is Ellery Queen: Don't Look Behind You, from 1971. They wrote the script but are credited as 'Ted Leighton'.

So the story goes, the duo were lifelong Queen fans, and jumped at the chance to write a pilot for a Queen series. They chose to adapt the novel Cat of Many Tails, a serial killer story, and the result was Don't Look Behind You. However, while they were off on holiday with their wives (at Universal's expense, Link explains in an interview I found on Youtube), the producer decided to make changes to the script that they disliked intensely. Another misfortune was the casting of Peter Lawford as Ellery Queen.

Lawford was very well-known in his day, but although he'd lived in the US for many years, he was English, and his smug smoothie persona, was quite unlike the character of Queen as almost everyone envisages him. In addition, his range as an actor was limited. One can well imagine the dismay that Levinson and Link felt. No wonder they disowned the script.

It's a real pity, because the story has some potential - the quest to find the link between seemingly unconnected killings in a series can be fascinating. This film does have its moments, although not as many as one would wish. What's more, the cast benefits from the presence of Stefanie Powers. However, Inspector Queen in this version is Ellery's uncle, rather than his father, and the script's attempt to update the relationship doesn't work well. The Jim Hutton series was, from what I have seen of it, a significant improvement, because it made a determined attempt to stay true to the spirit of the original stories.

February 15, 2021

Bowler Hats and Kinky Boots by Michael Richardson

I was lucky enough to grow up in the Sixties, an exciting time for popular culture in Britain. The Beatles, Bond movies, The Prisoner, and much, much more. One of my favourite TV programmes as a young boy was The Avengers. I never saw the early Ian Hendry or Cathy Gale episodes - my introduction to the series (which my parents enjoyed hugely) was with the arrival of Diana Rigg as Emma Peel. And so I've been interested to dip into a reference book about the series published a while back by Telos.

Bowler Hats and Kinky Boots is described as 'The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to The Avengers'. Well, it may not be authorised, but it certainly doesn't lack authority. It's a weighty tome, and Michael Richardson must have put a huge amount of work into writing it. The detail (which extra played a stuntman, that sort of level) is at times almost overwhelming.

So, for instance, there is material about unmade episodes (such as 'unmade wild west episode') as well as accounts of how scripts evolved and background info, including mention of a failed rival to the series, The Unusual Miss Mulberry, starring another Diana - Ms Dors - which was never made. The TV world, as I know all too well, is unpredictable. Series that seem to promise much never reach the screen. Series that are made might have been better left in the cutting room. To a large extent, it's a game of chance. But The Avengers went on for year after year. Whilst I think that a decline set in after Diana Rigg left, there was much to enjoy in some of the later episodes.

The point is made that fun was a key component of The Avengers. Yes, the storylines were outlandish in the extreme, yes, they were 'of their time', but the tales were told with such panache that the results, when the series was at its peak, were consistently enjoyable. Michael Richardson's book is a pleasing and in-depth companion to a classic example of television at its most entertaining.

February 12, 2021

Forgotten Book - Sudden Death

Sudden Death was published in 1932, at a period when Freeman Wills Crofts was experimenting with the traditional detective story. Here he offers a locked room mystery, with not one but two 'impossible crime' scenarios. These have received high praise from astute locked room fans such as Jim Noy of the Invisible Event blog, which indicates that Crofts did a good job of the practical technicalities of mystification.

I'm a fan of locked room mysteries myself, very definitely, but I prefer those which have a touch of the baroque about them. Why? Because the locked room situation is essentially improbable, I think its treatment needs to be something out of the ordinary. Its appeal is that of the paradox - which is why G.K. Chesterton enjoyed writing 'miracle problem' mysteries, some of them first-rate. John Dickson Carr was especially good at laying on the atmospherics. Crofts' plain prose seems to me less well-suited to this type of writing. He had a gift for engineering technicalities, so this book is not short of diagrams or detail as to how the tricks were worked. But for me, the appeal of these things is reduced if I don't have the sense of the dazzling conjuring trick which is a large part of the appeal of the stories of Carr (and of other locked room specialists, such as Clayton Rawson). I enjoy being bamboozled in a melodramatic way, but the minutiae of howdunit don't excite me, maybe because I'm hopelessly impractical myself.

More interesting to me, as a writer certainly but also as a reader, is a point highlighted in the blurb of the first edition: Crofts 'constructed his mystery on novel and interesting lines. The action of the book is seen alternately through the eyes of two persons, Anne Day...and Inspector French.' The shifts of viewpoint are done pretty well, in my opinion. Anne takes a job as a housekeeper with a man called Grinsmead (who happens to be a solicitor, although his profession isn't significant) and eventually forms a bond with Sybil Grinsmead. Sybil is convinced that her husband is having an affair and wants her dead. And guess what? Sybil dies. But in a locked room...

We think we know what is going on, but Crofts does have a significant plot twist or two up his sleeve. The trouble is that I wasn't convinced by the psychology of the culprit. Would this person have committed crime in that way? I wasn't persuaded that the answer was yes. At the time this book was written, the leading detective novelists were becoming interested in the psychology of crime, and Crofts himself ventured into this area in some of his books, with rather mixed results. Here, his prime focus is on method. This is a readable mystery, and Crofts' desire to try something new deserves praise. Even so, this is not one of my favourites among his books.

February 10, 2021

Mind Games - 2001 TV drama

It's twenty years since Mind Games, written by Lynda LaPlante, aired on TV, but I only caught up with it recently. I must admit I'd never heard of it before, but the summary sounded tempting and there's no denying that Lynda LaPlante is a highly accomplished exponent of TV crime drama. I still recall the brilliance of the original Prime Suspect, one of the outstanding shows of its day. Helen Mirren was superb as Jane Tennison but the script did her proud.

Mind Games benefits from having another talented actor, Fiona Shaw, in the lead. She plays Frances O'Neill, a detective inspector who has made a specialism of criminal profiling. She's quite obsessive about her work and there's a touch of mystery about her past. I don't think it's much of a spoiler to say that she is soon revealed to be a former nun. Quite a backstory...

She's called in to assist following the discovery of a ritualistic killing, the second in a few days. Both victims were women, who were bound to a chair in their own homes. But the houses weren't broken into - so why did the victims admit their own killers? A local plumber who was having an affair with one of the dead women and seems to have a connection with the other is the obvious suspect. But we know better than to concentrate exclusively on the obvious suspect, don't we?

The story is told with the pace that is necessary to ensure the suspension of the viewer's disbelief. The supporting cast, including Finbar Lynch and Chietal Ejiofor, is strong, but this is Fiona Shaw's show. It's interesting to look back on the cutting edge forensic science and forensic psychology deployed in the storyline and to see how much has changed over twenty years. Profiling remains highly relevant, but I don't think people have as much faith in it now as they did then. But I'm rather surprised that Frances O'Neill didn't become a series character. She seems to have been created with that in mind, but it never happened. She's very different from Jane Tennison but that backstory had a lot of potential...

February 8, 2021

Ann Cleeves' writing and The Darkest Evening

I've had the pleasure today of reading a brand new Ann Cleeves story featuring Vera Stanhope which is destined to appear in a new anthology later this year - more about this project in due course. Ann is at least as good a short story writer as she is a novelist, and that is saying something. On the blog this year, I want to talk about a few of my favourite contemporary crime writers, and I'll start with Ann, whose latest novel, The Darkest Evening, is a Vera novel and about to appear in paperback.

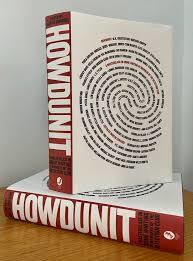

When I was working on my first novel at the end of the 1980s, I looked closely at the work of a good many writers, including in particular a group of talented young authors who had emerged in the past few years. These writers were doing some things with the crime story that especially appealed to me, and the fact that they had broken through to become published authors was encouraging, even if they set the bar quite high. They were: Andrew Taylor, Liza Cody, Peter Robinson, Ian Rankin, Frances Fyfield, and Ann. I didn't know any of them personally, of course, but I admired what they were doing with the genre. Although each author has to find his or her own way, you can learn a lot from other people with whose work you are in sympathy. And the truth is that you never stop learning. Which is part of the rationale for Howdunit, to which all six of those writers, now all fellow members of the Detection Club, have made splendid contributions.

Ann's books sell in the zillions these days. We live in a commercial world and sales are naturally driven to a significant extent by the success of two high profile TV series, with another, featuring Matthew Venn, in the works. But the key point is that Ann was a very enjoyable writer long, long before she became a bestseller. As with the other writers I've mentioned, I've been a fan from the outset (indeed, her debut novel is now marketed as a 'Pan Heritage Classic') and I've benefited from many discussions with her about the craft of writing and the writing life. I'm sure that right now erudite people are working on scholarly studies of her books. Here are just a few observations of my own.

The Darkest Evening is set at Christmas. Vera is driving when she gets lost in a blizzard. She happens upon an abandoned car with a small child strapped in the back seat. When she seeks help at a nearby house, she finds that it is Brockburn, where her late father grew up, and which is still in the family. Then a body is discovered in the snow. Notwithstanding her personal connections to some member of the household, she begins to investigate...

There are vintage ingredients here (Lord Peter Wimsey's car was also stranded in The Nine Tailors, for example) but I see this book as belonging to the broader tradition of the country house mystery, dating back to Wilkie Collins' The Moonstone, rather than the Golden Age specifically; Ann is less interested in clueing and puzzle-making than she is in depicting people and place.

She has always excelled at the evocation of landscape. Like Ellis Peters and P.D. James, she is especially adept at capturing the spirit and personality of the British countryside. 'Human Geography', her essay in Howdunit, is a very good explanation of her approach. Her treatment of individuals - not just her empathetic lead detectives - is always sensitive, while the themes and mood of her novels are consistently interesting. Her title comes from Robert Frost, and her use of Frost's poem gives The Darkest Evening extra resonance.

Ann is prolific, and it won't be very long before she writes her fortieth book. There is always a challenge for a writer who produces so much: how can I avoid the formulaic? One way is to employ innovative structures and storytelling methods - Reginald Hill, for instance, was a master of this method. Ann's novels generally follow a traditional pattern, but what she has done is to write no fewer than five series, each with distinct (predominantly rural) settings in different parts of the country. She tends to alternate between different series, and this is one of the techniques that has enabled her to keep things fresh. And it has worked well, to such an extent that The Darkest Evening is in my opinion one of her best books.

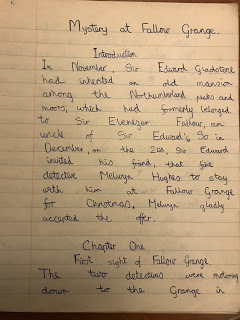

Mind you, I have pointed out with rather cheeky glee to Ann that she's not the first person to come up with the idea of a country house mystery set at Christmas in Northumberland. Let me refer you to Mystery at Fallow Grange, second in the Melwyn Hughes series, written when I was ten years old - talk about great minds thinking alike! At that point, I'd never been to Northumberland, and it sounded like a remote and exotic place. And for connoisseurs of the deservedly obscure, here's the first page of that mysteriously unpublished masterpiece:

February 5, 2021

Forgotten Book - Candidate for Lilies

Candidate for Lilies, first published in 1934, illustrates both his strengths and his weaknesses as an author. It's a well-written novel with a genuinely interesting central idea. Yet one feels it could have been so much better. Now that may seem a harsh verdict. After all, Kirkus Reviews (not easily pleased) admired the novel on its American publication. More recently John Norris, a shrewd judge, has sung its praises on his Pretty Sinister blog.

The initial set-up is a familiar one. A rich old person, in this case Uncle Arnold, invites penurious family members to his mansion in the country, only to break the news that he's planning to change his will. As usual in Golden Age novels, the would-be testator duly gets his come-uppance. He's stabbed to death with one of his own Italian daggers, and we don't mourn him.

There's a restricted pool of suspects, and East's focus is as much on character and motive as on whodunit. As a result, the novel has an unorthodox feel to it, hence the critical praise. Today, when sophisticated writing in the crime genre is common enough, we may take East's ambition almost for granted, and I'm sure he could have made more of such material. But he could certainly write. Incidentally, the East name concealed the identity of Roger Burford (Roger d'Este Burford, to be precise!) and he was a Cambridge chum of Christopher Isherwood who worked in the film industry and later wrote for television. He deserves to be better known.

February 3, 2021

The Art of Reginald Heade

A few weeks ago, I discussed Cover Me, Colin Larkin's excellent study of Pan paperback cover art. This book is published by Telos (who also publish crime fiction, notably the work of Priscilla Masters) and I've now received from them two more lavishly illustrated books depicting cover art from paperbacks of long ago. Both books deal with the work of one prolific artist, well-known in his day, Reginald Heade.

The two books are: The Art of Reginald Heade by Stephen James Walker, and The Art of Reginald Heade, volume 2, by Walker and Steve Chibnall. The central challenge in publishing books of this kind is to ensure that the quality of the illustrations is of a high standard. And Telos rise to that challenge.

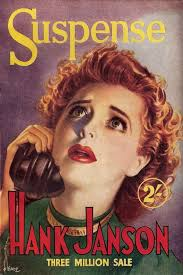

I didn't know anything about Heade or his work before reading these books, though by a coincidence I see that one of his earliest covers was for a paperback original story by Francis Beeding, The Errant Under-Secretary, which was recommended to me recently. During the course of his career, he produced covers for many notable writers, ranging from John Steinbeck, Pamela Hansford Johnson, and Anne Frank to thriller writers such as David Hume and Erle Stanley Gardner. His covers adorned magazines, children's books, romances, and westerns. He produced artwork for comic strips and jigsaw puzzles. He is, however, perhaps most closely associated with the work of Hank Janson, which I have to say doesn't appeal to me in the slightest. Titles like Hotsy-You'll Be Chilled, Slay-Ride for Cutie, and Death Wore a Petticoat speak for themselves. Unfortunately.

But just as you shouldn't judge a book by its cover (though sometimes you can...), so one shouldn't judge Heade by the authors whose covers he designed. He was a highly professional artist, and did what he was tasked to do very efficiently. I find the discussion of his life interesting - and rather sad. I'm not sure I've ever read a story about an artist who specialised in book covers. Thanks to Telos, and these titles, I'm now strongly tempted to write one....

February 1, 2021

Unnatural Death Revisited

Unnatural Death was Dorothy L. Sayers' third novel, first published in 1927. I first read it when I was very young. At that time I'd read one or two Lord Peter Wimsey novels, but my idea of a detective story was heavily influenced by Agatha Christie and I struggled with a book where it was pretty obvious from an early stage whodunit. I admired Sayers' writing enough to persevere with her work and in time I became a real fan, but although I've dipped into this novel several times, I thought it was about time I read it from cover to cover again. What would my reaction be this time?

It's an interesting story in terms of composition. It's pretty clear that Sayers started with, or conceived at an early stage of writing, two distinct ideas for puzzles or plot twists. Both were ingenious and interesting. One was inspired by a topical legal issue. The other was a bit of medical know-how (which, it must be said, has been much debated over the years, and is to say the very least rather questionable). Upon these foundations she built a rather unusual story.

It begins with a chance conversation between Wimsey and his policeman friend Charles Parker and a doctor, who tells them a story about an elderly woman's death which he found suspicious. Wimsey is intrigued, and investigates with the aid of his entertaining sidekick Miss Climpson. This novel has never been televised, but if it was adapted, I feel sure a scriptwriter would want to show, rather than tell, what happened to the old lady before her death. Sayers' lack of experience in structuring a novel is rather evident in the early chapters.

The characterisation is fascinating. There are several women in the story who are evidently lesbians, but the mores of the time meant that their sexual orientation is addressed indirectly. Sayers also introduces a character who is significant in relation to the plot and who is black, something uncommon in detective fiction of the Twenties. He's presented very sympathetically, although the language of the time is racist. But you sense that Sayers was trying to do something unorthodox and courageous, even if she wasn't able to do so in a truly satisfactory way.

The killer's psychology is bizarre; there is a descent from ingenuity in murder to wild irrationality. It doesn't ring true, but again, despite the imperfections, one senses that Sayers was groping for a sophistication in writing that was rare in the genre at the time. Unnatural Death is, in short, the work of a writer who is serving her literary apprenticeship and who shows glimpses of great ability. She would produce better books, but there is rather more to this one than I realised when I first read it.

January 29, 2021

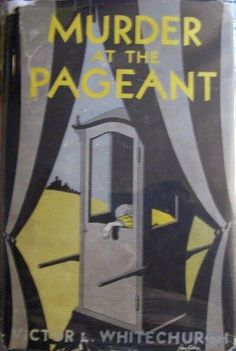

Forgotten Book - Murder at the Pageant

Murder at the Pageant was the penultimate novel of Victor Lorenzo Whitechurch (1868-1933) and was published three years before his death (my copy is the US edition, which came out a year later). By that time, Whitechurch's reputation as a detective writer was firmly established. His early railway-based short stories remain the work for which he is best known, but his first detective novel appeared in 1924 and he was one of the founder members of the Detection Club, contributing a chapter to The Floating Admiral.

This novel is typical by those of Whitechurch that I've read. The mystery is solidly constructed, the detective work sound, and the general tone (especially when the author, a Rural Dean, pokes gentle fun at members of the clergy) is agreeable and occasionally humorous. Everything is rather under-stated and very English (or at least very English in the way that people outside England tend to think of the English!)

The setting in and around a country house and small village contributes to the vintage atmosphere of the story. Not only is there a pageant, a sedan chair also features! A jewellery theft plays an important part in the story and this is, of course, a plot ingredient in the tradition of The Moonstone as well as many later Victorian mysteries. The plot is competently constructed and Whitechurch's lead detective, Superintendent Kinch, is hard-working and decent. Whitechurch was supposed to be one of the first crime writers to consult police officers in an attempt to make sure that his accounts of police work in his novels had a touch of authenticity.

Whitechurch wasn't really aiming, in novels like this, to break fresh ground in the genre. He wasn't a Sayers or a Christie, or even a Crofts or a Connington. His focus was on entertainment. His writing was of a higher quality than that of many other detective novelists of his time, and although I wouldn't claim that he was a master of heart-stopping tension - this story is simply too calmly told for that - they have considerable appeal . Especially in a pandemic, when light escapism has so much to commend it.

January 26, 2021

Howdunit and the Edgars

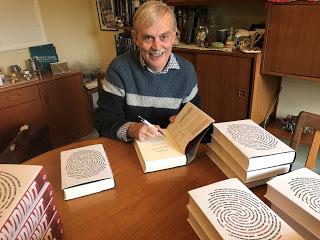

Champagne was quaffed in Chateau Edwards last night, and for good reason. I'm happy and proud to report that Howdunit has been shortlisted by the Mystery Writers of America for an Edgar award. The Edgars are the longest-established and most prestigious of the US crime writing awards, so this news certainly represents one of the highlights of my career. It's timely to mention once again how grateful I am to all the members of the Detection Club who helped me to compile the book. And indeed to the families and estates of deceased members, ranging from Agatha Christie to Jessica Mann, who allowed me to reprint pieces they'd written in the past, which fitted in splendidly with the key themes.

Putting this book together was one of the most interesting challenges of my writing life. What was striking was the utterly unexpected way that the project grew and grew and grew. The book also developed into a work that is, I think, quite unlike any other publication. This distinctiveness is something that one always hopes for - it doesn't, of course, always work out, but this time I was in luck. The idea was to celebrate the Detection Club's 90th birthday and to raise funds to ensure that it continues to thrive. So the contributors (and the editor, of course) were to donate their contributions without a fee. I assumed this would mean that we'd only have a limited number of contributors, and that was my original vision: a quite modest and compact project. But the enthusiasm of everyone to take part was quite wonderful. As a result, the book took rather longer to turn into a cohesive whole than I'd originally envisaged, but it was definitely worth it. A slim volume became, during the course of 2019, a very big book indeed...

The Edgar awards will be celebrated on 29 April, but I will not be in the US this time, for obvious reasons. A shame, but inevitable. I am very lucky, however, to have wonderful memories of my previous visit to the Edgar awards, five years ago. It was a marvellous occasion, made all the more unforgettable by the fact that The Golden Age of Murder actually won.

Win or lose, though, I'm honoured to join that relatively small band of British authors who have been nominated for an Edgar more than once. And I hope that the nomination will encourage more readers to sample Howdunit and to enjoy the collective wisdom of some of the best writers in the business.