Martin Edwards's Blog, page 71

August 13, 2021

Forgotten Book - A Sort of Virtue

Julian Symons' final novel is the least-discussed of all his books, in part no doubt because it was published after his death. A Sort of Virtue is an oddity in a number of ways, not least because it marks the second appearance of the Scotland Yard man Hilary Catchpole. So Symons, the scourge of series characters, ended his career with a mini-series, albeit of just two books (Hilary previously appeared in Playing Happy Families).

Another curiosity is that this novel is presented as 'a political thriller', a type of writing with which Symons wasn't closely associated. He wrote the book during the years of the John Major government, and Major is given a name-check in the text, but has retired from the fray before the events of the story take place. There's quite a lot in the story about the inner workings of government, but this material is presented in a rather detached way and I have to say that I didn't get any impression of inside knowledge about the workings of government.

The story begins with the discovery of a murder. The dead woman is Lily Devon, a high-class prostitute. An initial police investigation is manipulated by outside forces, and duly bungled. An attempt to pin the killing on an innocent man fails, but only because Hilary - of all people - can give him an alibi. It then falls to Hilary to find out what really happened.

Julian Symons wrote this book at a time when he was suffering from cancer. The novel is longer than most of his books and I wonder if, had he lived, he would have edited it more extensively. I like to think so, because the story is meandering, to say the least. Characters flit in and out of the story and for long periods, not much happens. Quite a lot of the dialogue and description. particularly in relation to minor characters, seems dated by the standards of the 1990s, never mind today.

Because he was a very good writer, there is still some interest in many of the scenes, but the magic that I associate with Symons at his best is absent. There is one minor character, a rather typical Symons figure, who seems enigmatic and who I felt was sure to play a key part; but in the end the explanation for his mysterious activities was anti-climactic in the extreme. The basic murder mystery plot is okay, but overwhelmed by endless digressions that aren't especially interesting. I really, really wanted to love this book, but I can't deny that I found it a disappointment. I'm afraid it's one for the Symons completist only.

August 11, 2021

A return visit to The Crooked Shore

A full day trip to the Lake District - at long last! I was glad to take advantage of a fairly positive weather forecast to take another look at one of my favourite areas in the world, and some of the settings for The Crooked Shore. I have a vivid memory of the day I discovered the tiny village of Aldingham on the south coast of Cumbria and realised that it would make a perfect setting for the story I had in mind. I made a few changes, transplating a manor-converted-into-flats from north Wales to Cumbria, and introducing a few topographical changes, but Aldingham was certainly inspirational and it was good to go back.

I also took a quick look at Bowness, home to Kingsley Melton, who plays such a key part in the story, and also the place where Ramona Smith was last seen more than twenty years before the action of the story begins. After that, we drove through Ambleside to Grasmere for lunch at the Swan, where a few years ago I had the pleasure of giving a talk to a group of American visitors which included my dear friends Caroline and Charles Todd, who were researching for one of their own novels.

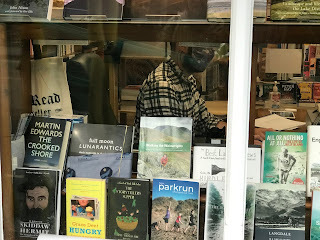

A walk into Grasmere village naturally took me to Sam Read's brilliant bookshop. There was a long queue outside, so I didn't go in, as independent shops need all the customers they can get without being interrupted, but it was heart-warming to see so many people so eager to look for books. And very gratifying to see The Crooked Shore in the window!

After that, a lovely trip over the dramatic Kirkstone Path to Ullswater, where the events of The Frozen Shroud take place, and Pooley Bridge - and my first sight of the new bridge, built after floods destroyed the old one. I was startled to realise that it's more than six years since I was last there on a research trip, but again it was good to see how busy everywhere was and I hope this means that the economic impact of the pandemic is being mitigated to some extent. It will be a while before I write another Lake District book, since I have a contract to produce two more Rachel Savernakes, but this trip was a reminder of what a gorgeous and inspirational part of the world it is. Great to be back, and a great way to celebrate the new book, which incidentally has been Cumbria Life's book of the month.

August 9, 2021

Murder by the Book - publication week!

It seems like only yesterday that The Crooked Shore was published. I'll be talking more about my new novel shortly, but this month, I'm in the unusual and fortunate position of having two anthologies to celebrate. Later in August, the Murder Squad collection Many Deadly Returns will be published by Seven House, and I'll be launching the book along with my Murder Squad colleagues at Forum Books in Ann Cleeves' home town of Whitley Bay.

But this week sees the appearance of another British Library Crime Classics anthology. Murder by the Book is sub-titled 'Mysteries for Bibliophiles' and I gather that advance sales have been extremely good (which is always nice to hear). So much so that there is already a possibility that I might be putting together a second book on a related theme, though nothing is yet settled.

Again, I'm scheduled to do a bookshop event - this time at Toppings in Ely, later in the month. So if you're in that area, do check out the Toppings website for details. It's so good to be getting back into bookshops - I've missed them very much during the lockdowns. And I'm enjoying the chance to get around the country as well, which is genuine compensation for those cancelled overseas trips (for instance, I decided some time ago, with great regret, not to travel to New Orleans for Bouchercon, and now sadly the whole live event has been cancelled).

As you can gather from this spate of publications, I have at least been able to keep busy with writing projects during the past eighteen months and in many ways the time has flown by. During that time I've also signed a contract to write two more Rachel Savernake books. One of them, Blackstone Fell, is already written. And before long it will be time to start on the fourth in the series. Meanwhile, there is a further project that has kept me occupied, and that will be announced shortly...

August 6, 2021

Forgotten Book - A Little Less than Kind

Charlotte Armstrong's A Little Less than Kind can be read on its own merits as an unusual novel of domestic suspense, concerning the suspicions of a young man, Ladd Cunningham, that his father was murdered by an old friend called David Crown, who has now married Ladd's mother and taken control of the family business. Alternatively, one can pick up the clue in the title and read the story as a Sixties riff on Hamlet with a fair dollop of Freudian psychology thrown in.

On the whole, I prefer the former approach. The set-up is full of potential. Hob Cunningham was dying of cancer, but Ladd's prejudice against David leads him to suspect that David hastened Hob's death. His interpretation of events seems, to him, to be justified by a coded message Hob has left behind. Ladd determines to kill David, and his attempts to cause mayhem become increasingly deranged.

The story offers lead characters who are equivalent to those in Hamlet, but Armstrong is not attempting to rewrite the play, but rather to do something different inspired by the ideas in the play. She's interested in the relations between parents and children, a key theme of the novel, and in the question of taking responsibility. David's new wife Abby, who believes in courtesy and avoiding any hint of an argument, is portrayed as charming but selfish and weak.

There is some good writing in this novel, particularly in the early chapters, and some building of suspense. But then the story begins to drag, and the finale, though not short of action, is rather anti-climactic. It's almost as if Armstrong's interest in Shakespeare and psychology derailed the story I wonder if she began with an idea which she didn't think through fully? It's an intelligent book with pleasing aspects but not a complete success.

August 4, 2021

Abi Silver - The Power of Fairy Tales - guest blog

When I was Chair of the CWA, I enjoyed meeting members up and down the country, and among them was Abi Silver (pictured), whom I met at a very pleasant regional chapter lunch. She is a fellow lawyer as well as a crime writer, and I'm pleased to hear she has a new book out. Here's a guest blog post from her, on a topic of timeless interest:

'Britney Spears was in the news recently, not promoting her music, but making an emotional speech to a US court, in an attempt to extricate herself from what she termed an ‘abusive’ and ‘controlling’ conservatorship arrangement. This sparked a flurry of interest in all things Britney, including (perhaps surprisingly) her professed admiration for Albert Einstein; she had been quoting the late Nobel-prize winning physicist’s views about the importance of fairy tales to stimulate critical thinking.

But fairy tales come in different shapes and sizes. The ones adapted by Disney tend to involve a struggle between obvious personifications of good and evil, where the hero is required to use quick wits, ingenuity and perseverance to succeed (most likely the kind of stories Einstein was referencing). Others are darker (think The Tinder Box and other Hans Christian Anderson tales) and it’s less easy to find any clear moral message. By way of example, I have just written ‘they want the fairy tale!’ into the first draft of my latest offering, to illustrate a menacing demand by some nameless sponsors to achieve everything their hearts desired.

And whilst many writers argue in favour of reading these pithy, mythical stories to their nation’s children, there is certainly a fair weight of opinion in the opposite direction, with others also expounding the view that The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins was not the first crime novel; that honour should instead be bestowed on a whole series of much older tales. Crime fiction is, after all, most often about retribution and the restoration of justice. The same could certainly be said of Cinderella (a tale of child cruelty), Hansel and Gretel (attempted murder of children) or Jack and the Beanstalk (an elaborate fraud which excused theft of the most precious items).

But what cannot be challenged is the ubiquitous nature of fairy tales with their universal themes, which has influenced countless contemporary stories, including, I’m not ashamed to admit, my own.'

**

Abi Silver is the author of the Burton & Lamb legal thriller series. Her latest story, The Midas Game, is published on 5 August 2021 and available here The Midas Game by Abi Silver | Eye Books (eye-books.com) or here https://amzn.to/3hqUGDy

You can also find her at www.abisilver.co.uk Abi Silver (@abisilver16) / Twitterand (2) Abi Silver, Author | Facebook

August 2, 2021

The Locked Cabin and Best Mystery Stories of the Year - edited by Lee Child

I was chuffed, to say the least, when my story 'The Locked Cabin' was chosen to be included in The Best Mystery Stories of the Year 2021. And it's good to learn that the book has been given a starred review in Kirkus. This is what they have to say:

'Editor Child, series editor Otto Penzler, and their colleague Michele Slung team up to offer 20 gems from 2021 in the first volume of a new series.

Many of this year’s best follow a familiar road: pitting a rugged male hero, often with military street cred, against the bad guys. Doug Allyn’s “30 and Out” features an Afghan War vet who hunts a colleague’s killer; Jim Allyn’s ex-Army police veteran worries about being teamed with an unreliable partner in “Things That Follow.” But a surprising number include less traditional crime busters. A young man entranced with the Irish language is the gentle hero of Andrew Welsh-Huggins’ “The Path I Took.” Sara Paretsky’s V.I. Warshawski, a familiar female gumshoe, makes a welcome appearance in “Love & Other Crimes” along with the female proprietor of Wilde Investigations in Janice Law’s “The Client.” Moms get into the act in Alison Gaylin’s “The Gift” and Tom Mead’s “Heatwave.” So do new friends, in Martin Edwards’ “The Locked Cabin,” and frenemies, in Jacqueline Freimor’s “That Which Is True.” And in a startling tribute to the power of sisterhood, Joseph S. Walker shows how quickly female strangers can bond if the need is urgent in “Etta at the End of the World.” Women take starring roles on the wrong side of the law in John Floyd’s “Biloxi Bound” and Joyce Carol Oates’ “Parole Hearing, California Institution for Women, Chino, CA." Child’s selections seem especially appropriate for 2021, a year that promises change on so many fronts. The only exception is the unexplained bonus reprint, Ambrose Bierce’s “My Favorite Murder,” a bitter tale of a man who revels in the sadistic murder of his uncle. That one belongs to 2020.

Diverse and diverting.'

July 30, 2021

Forgotten Book - The Diehard

In the 1950s, Jean Potts was one of the leading female exponents of domestic suspense. She specialised in low-key stories and slow-burning tension, and this style isn't to every taste, but she was very good at what she did. My favourite of he books (at least, of those I've read so far) is The Little Lie, but The Diehard, published in 1956, is an interesting example of her work.

The subtlety of Potts' writing is illustrated in a very good first sentence: 'All through his wife's funeral Lew Morgan wrestled with a nervous, unseemly urge to yawn.' This is a very smart way of setting up an intriguing situation while casting unforgiving light on character - in just fifteen words. Within the first paragraph we learn that the funeral is taking place in Turk Ridge, evidently a small American town, and that a yawn would be 'the final, outrageous signal of disrespect'.

Naughty Lew. He's superficially pleasant but fundamentally selfish and capable of acts of cruelty. He has already lined up his next wife, with whom he's been carrying on for ages. Before long, it's evident that a whole range of people have good cause to wish him out of the way. What's more, elderly Aunt Chat has had a Sign that 'something terrible is going to happen'. This is a classic set-up for a whodunit. We expect Lew to be murdered, and the bulk of the story to be devoted to an investigation into the crime.

Except that isn't what happens. Instead, the tension continues to build. And when a death finally does occur, Lew is not the person who dies. Surely he isn't going to escape his fate? What's more, Lew realises he is at risk: 'nobody's going to try and kill me and get away with it.' For me, the tone was just too subdued to make me love this story as much as I wanted to; nevertheless, it's an admirable example of Potts' restraint and ability to depict character and present a picture of American life in her time.

July 28, 2021

The Conversation - 1974 film review

In my first year as a student, I was very keen to learn - not just my subject, but about culture and history much more generally. I'd worked for six months in a factory and I seized the opportunities that suddenly opened up before me to try to broaden my mind and understanding of the world. I didn't do everything I aimed to do - not by a long chalk - but I did see a lot of films. Among them was Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation. During the early scenes I was puzzled, but I quickly became hooked. I came away from the college where the film was being shown stunned but enthralled. I've just watched it for the third time and I remain a very big fan of this movie. It's subtle, clever, and engrossing.

The memorable opening scene is at Union Square, San Franscisco. A few years ago, I stayed at a hotel just by the square, and those memories came flooding back as I watched Gene Hackman, as Harry Caul, mounting a surveillance operation on a young couple who keep moving around in the crowd. Harry has been hired by 'the director' to find out what this pair are saying to each other. And Harry is the best in the business.

The key plot strand concerns Harry's attempt to understand the meaning of the conversation that he is listening to. This final plot twist here is brilliantly done - I'd call it Christie-esque in its combination of simplicity and excellence. But there's much more on offer here than mere plot (good though that is). Personal privacy is a central issue, one which is even more relevant today than it was in 1974. You only have to compare the recent British film Framed to see how tricky it is to deal with such a subject successfully, but Coppola's film really does make us think in a way that Framed does not.

And then there's the portrayal of Harry himself. Hackman is at his very best, capturing the man's loneliness and insecurity in very few words (the title is, in one sense, ironic: there isn't really a lot of conversation in this film). A terrible incident in his past fuels his paranoia. And this is one of those stories where paranoia is absolutely justified. The supporting cast includes Harrison Ford in an early role, and Teri Garr as Harry's lover, while Allen Garfield has a small but memorable part as Harry's competitor - is excellent. It's one of those films that stands up to repeated viewings and close examination, because it's the work of a gifted writer-director at the very top of his game.

July 26, 2021

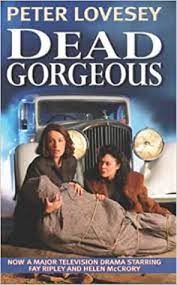

Dead Gorgeous - 2002 TV film review

Quite apart from his various series, Peter Lovesey has written several excellent stand-alone novels. One of my favourites, although it is not perhaps one of his best-known titles, is On the Edge, published in 1989. In 2002, it was televised as Dead Gorgeous, directed by Sarah Harding and with a screenplay by Andrew Payne. It's a story in the Strangers on a Train vein, but sufficiently distinctive to stand on its own two feet, and the TV version is, like the novel, very entertaining.

It's 1946 and two former WAAF 'plotters' are not enjoying married life. Rose (Fay Ripley) is treated like a domestic servant by her husband Barry, who keeps her short of money but spends a lot of his time out drinking and womanising. Antonia (Helen McCrory, who sadly died earlier this year) has, on the surface, done better for herself. She's married a wealthy domestic goods manufacturer called Hector (Ron Cook). But he bores her, and she's conducting an affair with a handsome young chap who has just been offered a new post in the US.

Rose and Antonia bump into each other and confide their matrimonial woes. Antonia, glamorous and mischievous as well as selfish, decides that they'd both be much better off without their respective husbands. From that moment, the pair are heading towards a potential exchange of murders.

Ripley and McCrory are a very appealing duo and the chemistry between them is such that, even if you guess what is likely to happen, there's a lot of pleasure to be had in watching events unfold. This is a nicely paced piece of light entertainment, and Payne's script and the acting do the novel justice.

July 23, 2021

Forgotten Book - Murder of a Man Afraid of Women

Anthony Abbot was a pen-name adopted by Fulton Oursler (1893-1952), who is best remembered as the author, under his own name, of The Greatest Story Ever Told; he told it some years after giving up on detective fiction. During the Thirties, though, he was one of the leading American writers of Golden Age mysteries. His books aren't easy to come by now, but on a recent visit to Hay I snaffled a copy of Murder of a Man Afraid of Women (1937). The US edition of this book, as with the five earlier books in the series, added the words 'About the' to the title, presumably to secure some sort of alphabetical primacy.

Abbot's detective was Thatcher Colt, head of the New York police. Colt is an interesting variant on the Philo Vance/Ellery Queen type of character. He's a police professional, with a keen understanding of the importance of technological advances in the fight against crime. But like Van Dine and Queen, he has the brilliance of the great detective, as well as an admiring narrator - his secretary, who goes by the name Anthony Abbot...

This novel was clearly inspired by a fascinating real life murder case in the US - the unsolved killing of the actor and director William Desmond Taylor. The true crime is an amazing story, and Oursler clearly used his imagination to think of a possible interpretation of the real life events, while adding plenty of invention to the mix. It's not a bad method at all.

It's not a bad book, either. I felt it began well and ended fairly well, but there was quite a bit of sagging in the middle of the story. I dreamed up my own solution, but it was way off beam, predictably so since it wouldn't have been acceptable given the moral climate in the 30s. There's an attempt to create a race against time, since Colt is trying to solve the case before his imminent wedding, but I didn't find this element of the story believable. There are some very interesting ingredients in the mix, but I wasn't entirely convinced by the overall handling of them, and in particular not by the all-important psychology of the main character, Peter Slade (who stands in Taylor's shoes in the story). There is too much contrivance. But of course that can be said of many Golden Age novels, can't it?