Martin Edwards's Blog, page 66

November 5, 2021

Forgotten Book - Dead on Time

Nigel Moss is a connoisseur of vintage detective fiction who has recommended a number of interesting writers to me. He was the very first person to encourage me to read John Bude, about a decade ago - some time before the British Library commissioned me to introduce The Cornish Crime Murder and The Lake District Murder. And he was also the first to urge me to give Clifford Witting a try. I made a slowish start with Witting, but the more I've read him, the more his agreeable writing has grown on me.

Dead on Time, first published in 1948, is a good example of his work. It's a murder mystery that isn't lacking in ingenuity. I read this book immediately after finishing a decent effort by John Rhode. One similarity is that in this book, like a number of Rhode's, the good old English pub plays a prominent part in the storyline. The Blue Boar in Lulverton is the scene of the fatal poisoning of Jimmy Hooker, and a plan of the ground floor of the inn is duly provided.

The criminal's modus operandi here is crafty enough to be worthy of Rhode, but its strength lies in its simplicity, whereas Rhode's schemes are often highly complex. As a general rule, Witting scores over Rhode in terms of characterisation and prose style.There's a lightness, a touch of good nature about his storytelling (as with Bude and indeed George Bellairs) that has genuine appeal. Rhode was capable of pleasing touches of humour, but he was much more prolific than Witting, and such industry, although admirable, isn't conducive to elegant writing.

The first half of the book is very enjoyable, but the story becomes thrillerish and less engaging prior to a good climax and the revelation of the pub killer. Not a masterpiece, then, but a decent story, well worth reading. And yes, the rabbits on the dust jacket cover are relevant to the story...

November 3, 2021

A piece of Detection Club history - guest blog by Tina Hodgkinson

I'm always glad to learn more about the history of crime fiction in general and the Detection Club in particular, so I was delighted when Tina Hodgkinson,came up with some original research and kindly agreed to contribute the following guest post:

'When I was recently preparing a talk for the Agatha Christie Festival, I contacted Martin about the Detection Club’s premises in Kingly Street, Soho which was briefly mentioned in his very informative The Golden Age of Murder. Kingly Street is the parallel road in between Regent Street and Carnaby Street. Given the redevelopment of the area, I was going to have to explore historical documents to see if they could provide a clue to the location. I’m very fortunate to work at the London Metropolitan Archives, so thanks to Mark Arnold, from the Public Services Team, for pointing me in the direction of the 1934-1940 London ordnance survey maps. On the map I found St Thomas's Church on Kingly Street, and as this looked promising, I booked a visit to the Westminster Archives, to view all the documents they had pertaining to the church, which included drainage plans and a correspondence file from the 1960s. Thank you to Cecilia and Hillary for all their assistance. Here’s a brief summary of what I found.

Opposite the site of the former church, was St Thomas’s Vicarage at 12-13 Kingly Court. The Vicarage was a striking, substantial, red brick and sandstone building with a decorative, gabled attic and a basement. It dated from 1887 and was designed by Lansdown and Harris. From 1932, the top floor and the attic were converted into a self-contained flat for the vicar, while the remainder of the building was leased out for business purposes. The lower floors were used as offices, workshops and showrooms. By the late 1950s, the basement and the second floor were each rented as entire floors to two separate businesses. However, the office space on the ground floor was split into a two room and a one room rental, and the first floor as three single rooms. The correspondence I saw from the 1960s, listed the business tenants at the time, but there was no reference to the Detection Club or any of its members. However, based on the information we have, I think it is highly probable that the Detection Club met in St Thomas’s Vicarage. The best bit of all is that the Vicarage still survives. It is now a restaurant called Dirty Bones. Goodness knows what Eric will make of that!

P.S. If you want to visit Dirty Bones, there is a step free route from Carnaby Street to their Kingly Courtentrance. Staff informed me there is also an accessible toilet.'

November 1, 2021

Villa Volvo Vovve: guest blog by Catherine Edwards

I'm delighted to host, for the very first time on this blog, my daughter Catherine, whose first book has just been published. I was hugely proud of a terrific book about football history published by my father shortly before his death, a few weeks before Catherine was born in 1993, and you can bet that I'm proud of what she's achieved with Villa Volvo Vovve as well. Over to Catherine:

'If you are reading this blog, firstly, hello! Secondly, you’re probably interested in crime fiction and the craft of writing, so that’s what I’ll talk about.

There are a few different theories as to why Nordic noir became such a popular phenomenon. There’s no denying that the settings are deeply atmospheric. Something that stood out to me in my first winter was the silence of city evenings; the thick coats of snow have a muffling effect.

But despite the sometimes bleak winters, the real Sweden, along with its Scandinavian neighbours, have a very low murder and crime rate. It’s possible that the crime fiction trend is not despite that but because of it. Some of the most popular examples of the genre play on the contrast with peaceful landscapes -- not just Sweden, but cosy English villages, or the Lake District for example -- corrupted by cold-blooded killers. And maybe there’s an element of Schadenfreude, with readers taking pleasure from imagining that things aren’t so perfect as they look.

Sweden is neither the crime-ridden bleak landscape of your favourite deckare (the Swedish word for a detective novel), nor the utopia that you might be led to believe in if you read one too many magazine articles promising that the latest Nordic buzzword, be it hygge, lagom, or fika, will transform your life.

Sweden is a country marked by its contradictions -- like any country really, though perhaps to an extreme extent. It’s home to a liberal democracy, but has such restrictive alcohol policies that you can’t buy alcohol for home consumption after 8pm or at all on a Sunday. It’s one of the most technologically advanced nations (while living there, I met several people who had microchips inserted in their hands) yet its people prize nothing so highly as a weekend uninterrupted in nature, often preferring to leave their wooden summer cabins uncorrupted by the latest mod cons.

If you’re a crime fiction fan, you’ve probably read some works in translation. I was privileged to translate the story of Maj Sjöwall for a crime anthology, and I think crime novels are an excellent example of the difficulties of translation. A translator might reword a sentence when writing it in their own language, not realising that in doing so they deprive readers of a crucial clue.

Even in the short story I translated by Maj (Det var inte igår - Long time no see), there were plenty of sections that gave me pause for thought. The first passage presented me with a problem, using three Swedish words for snow, each with a specific connotation, none with a direct English equivalent.

The story opens with a homeless woman collecting bottles from a recycling bank so she could exchange them for cash using Sweden’s bottle deposit scheme. A similar scheme is now planned in the UK, but at the time the story was written it was completely unheard of there, so as a translator I wondered how much I needed to explain the system. In the very next scene, the main character uses the coins from the recycling station at the Swedish alcohol monopoly store, another concept that doesn’t exist in most countries.

Personally, I think one of the reasons people love Scandinavian settings for murder mysteries is that these are countries we generally don’t know much about -- the unknown quantity adds to the mystery. But if you’ve ever wanted to learn more about the real Sweden, my newly published book is for you. After six years living in and writing about Sweden as a journalist, together with my colleague Emma Löfgren, I’ve written Villa Volvo Vovve: The Local’s Word Guide to Swedish Life, which explores Sweden beyond the cliches and stereotypes, through the story of 101 Swedish words. The idea is to introduce a bit of the real Sweden, with all its contradictions and quirks, to people around the world, and it’s for anyone with an interest in language, culture, and the way they shape our perceptions.'

October 29, 2021

Forgotten Book - Shadow Show

Shadow Show, published in 1976, was the final book of Pat Flower's career. I've talked about Flower a few times in my blog, because although today she is an obscure figure, she is an author who interests me. Born in Britain, she spent most of her life in Australia, and after a number of detective novels she concentrated on novels of psychological suspense. Even in her hey-day, she was never high profile in her native land, but her later books appeared in the Collins Crime Club and Edmund Crispin was among the critics who admired her work.

Shadow Show is a novel of suspense and paranoia. Richard Ross, the protagonist, is essentially an innocent who finds himself entangled in a web of crime and coincidence. He is a young accountant in an export business and he suspects one of his colleagues, Athol Cosgrove, of corruption. But he dithers, characteristically, before doing anything about it, and his hesitation proves costly.

Before long, he is being treated as a prime suspect in a murder case. He tells a number of lies to try to protect himself, and inevitably sinks deeper into the mire. He has a lovely wife, Laura, but their marriage has been affected by the death of their young daughter, and although he is good at his job, and liked by his boss, his involvement - and growing obsession - with the deeply unpleasant Cosgrove is investigated by a shrewd and painstaking cop called Forrest.

Kate Jackson has previously reviewed this book and I agree with her that Ross is something of a wet blanket. His irritating naivete is the reason we don't sympathise with him quite as much as would be desirable if we were to become deeply absorbed by his troubles and deeply anxious about his fate. The challenge for an author writing a book of this kind is to persuade us that the unwise choices made by the protagonist were somehow inevitable, and this is easier said than done. Several times during the story I found myself groaning about Ross's errors of judgement.

And yet. This book does have something that kept me engaged throughout. Pat Flower was a highly capable storyteller and the very last sentence in the novel, nicely under-stated, is genuinely chilling and impressive. It is a terrible tragedy that, the year after the book appeared, Pat Flower - who had long been troubled by poor health - took a fatal overdose. Her work is definitely worth a look.

October 27, 2021

Get Carter - 1971 film review

I've mentioned Get Carter several times in blog posts over the years. As I've said, it is, along with The Long Good Friday, one of my all-time favourite gangster films and many would rate it even higher than that masterpiece. Back in 2010 I was glad to have a chat with the director Mike Hodges at CrimeFest. Mike has achieved a great deal over the years but I'm pretty sure that Get Carter is the film for which he'll be remembered, long into the future. It's a classic of its kind, and since - amazingly - it's 50 years since it was made, here's a review based on my latest viewing.

Just as Bob Hoskins is the key to the brilliance of The Long Good Friday, so Michael Caine is at the heart of everything in Get Carter. His performance as a one-man killing machine is superb, and there's also a rare touch of emotion at one point. But only a touch. There isn't anything quite as chilling as the final scene in The Long Good Friday, but there are lots of shocking moments, not least in the closing stages as Jack Carter's quest comes to a bloody conclusion.

Ted Lewis''s novel on which the film is based (and which really is excellent - the best British gangster thriller by far) was originally called Jack's Return Home. He' goes back to his roots in the north east following the mysterious death of his brother. Jack is a villain, and so, in a smaller way, was his brother, who was mixed up with villains including Cyril Kinnear, played with creepy menace by John Osborne. Ian Hendry, who was originally considered for the Caine role, plays Eric Paice, a nasty piece of work who meets an extraordinary end. The cast as a whole features some terrific performers,stalwarts of British television ranging from George Sewell, Alun Armstrong, Glynn Edwards, Terence Rigby, Bernard Hepton, and Bryan Mosley, as well as Britt Ekland in a minor but not to be overlooked role as Jack's girlfriend.

Fifty years on, this violent movie offers us insight into a past way of life just as interesting as, if very different from, the pictures of vanished lifestyles in vintage crime novels. The attitudes towards women are strikingly dated, needless to say. Jack Carter's world is a man's world, and it's frightening and very grim. But I don't think, taken as a whole, that it's a film in which Mike Hodges glamorised violence. On the contrary, it's really a movie about very bad things happening to very bad people. And it remains compelling.

October 25, 2021

Harry Devlin's 30th birthday

I find it hard - very hard - to believe, but this year marks the 30th anniversary of the publication of my first novel. Yes, Harry Devlin emerged way back in 1991, in All the Lonely People. In one sense, the appearance of that novel marked a culmination - I'd only ever had one career ambition, which was to publish a detective novel - but in many other respects it represented the start of something new, the beginning of my life as a published novelist. And it's a life I've enjoyed hugely ever since.

I'm absolutely thrilled that Acorn (also known as AUK Studios), the country's leading indie digital creator, is celebrating this anniversary by reissuing the seven Harry Devlin books I wrote in the 1990s with striking new cover artwork. The revamped books are available now, not only as ebooks but also in hardcover and paperback editions. They also include introductions from leading writers such as Val McDermid, Ann Cleeves, Andrew Taylor, Margaret Murphy, and Peter Lovesey.

All the Lonely People introduces Harry and he's soon in big trouble. His estranged wife Liz is murdered and he is the prime suspect. He wants to clear his name, and above all he wants to see justice done for Liz. My aim was to combine a gritty modern setting with a twisty plot in the Golden Age vein. Of course, it's no longer a modern story, but I hope it casts a little light on the way things were at the time.

The book did well for me. It earned terrific reviews in The Times (Marcel Berlins) and The Guardian (Matthew Coady) and also from Frances Fyfield, whose review said: 'More than adequate plotting and tremendous atmospherics...all in all a grand debut, well worth supporting. Buy it.' In later years I got to know both Marcel and Matthew, while Frankie Fyfield became a good friend (she also kindly wrote an intro for the reissue of the novel!). In those early days, though, the writing life was all very new to me and the warm words of these well-established commentators was a tremendous boost to morale.

So too was the news that the book had been nominated for the CWA's prize for the best first crime novel of the year, which has had various names over the years but which I tend to think of still as the CWA John Creasey Memorial Dagger. The winner was Walter Mosley and one of the great moments of my career came many years later in New York City, when I received an Edgar award on the same night that Walter was made a Grand Master of the MWA. Believe me, I never dreamed of that way back in 1991...

October 22, 2021

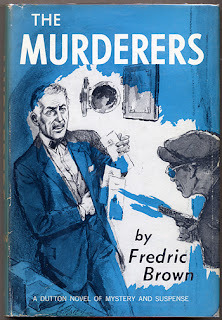

Forgotten Book - The Murderers

Fredric Brown is one of my favourite American crime authors and although he's best remembered for his science fiction, I think that some of his fiction is quite superb. He was adept at writing both novels and short stories (and sci-fi) and his talent for inventive plotting was remarkable. I'm not alone in admiring his work - other fans have included Umberto Eco and Stephen King. So he does have a very wide appeal.

It's taken me a long time to catch up with The Murderers, first published in 1961, and I was interested to see how it would measure up to his earlier work. By the time the novel appeared, Brown had moved to California and was involved in script writing. Like several other fine crime writers of his generation, he was very sceptical about Tinseltown and his cynicism about the film and TV business permeate the novel.

It's a first person narrative. Wally Griff, who tells the story, is a young, handsome fellow who has drifted to Hollywood and got a (not very good) agent and a number of minor parts. But professional success proves elusive. Wally has more luck when it comes to getting together with attractive women. At the start of the book, he's conducting a torrid affair with Doris Seaton, the glamorous wife of a wealthy businessman, but the cuckolded husband has hired a private eye to check on whether she is being unfaithful.

Wally meets Seaton and promises to give up Doris, but he's lying. It occurs to him that his problems would be solved if Seaton were dead, leaving him free to marry Doris. You can guess what's coming, can't you? This is a fast-paced story, and Brown is never less than readable, but it suffers from a lack of likeable characters - Seaton is by far the nicest person in the entire book.

Wally's brainlessness is as off-putting as his sociopathic tendencies and - unusually with Brown - the plot is far from original: the central idea has been used by others, sometimes famously, and done much better. Overall, despite the pace, it struck me as a tired piece of work. Brown's health was in decline at this point of his life, even though he was only in his mid-fifties. I'm sorry to say that, despite its undoubted grip, it doesn't hold a candle to his best books.

October 20, 2021

Martin Russell R.I.P.

Martin Russell was one of the unsung but highly reliable British crime authors in the latter part of the twentieth century. He was born in 1934 and I learned, from a comment on this blog by Betty Telford, that he died following a bout of pneumonia in 2019. I've been hoping that someone who knew him personally would publish an obituary of him, since he's a writer who has always interested me. But even in his lifetime he was never high profile, and there has been no mention of his achievements following his death that I've been able to trace. Nor is there any photo that I can find on the internet - the picture above is taken from the jacket of one of his books. I think he deserves to be remembered. So although I never met him, I thought I would try, to an extent at least, to fill the gap.

Russell's books were published by Collins Crime Club, from his No Through Road in 1965 to Leisure Pursuit in 1993. He published one book under the name Mark Lester and another as by James Arney, both of which were published by Robert Hale (whether these were digressions or books that Collins didn't accept, I don't know,and they are quite elusive).

Russell was born in Kent and spent much of his life in and around Bromley. He worked there as a journalist and subsequently joined the Croydon Advertiser group, later retiring to write full-time. This shows how successful he was as a novelist in financial terms- his books were published in such diverse countries as Germany, Italy, Finland, Spain, and Japan. He'd turned to crime after failing to find a publisher for some comic novels that he wrote. He never married, but enjoyed playing squash and tennis as well as jogging. He was also a crossword fanatic.

He was well-regarded enough by his peers to be elected to membership of the Detection Club in 1979 and he was also involved with the CWA, editing the members' newsletter Red Herrings. But he'd faded from the scene by the time I became involved with the world of published crime writers, which is why our paths never crossed. I've talked to a few authors who remember him and it's clear that he was a likeable man, modest and retiring. My guess is that he lost enthusiasm for crime writing. Perhaps the well of ideas ran dry. Perhaps he was disappointed by a lack of recognition for the often striking ingenuity of his stories. For whatever reason, he didn't stay in touch with the crime writing world, and his Detection Club colleagues hadn't heard from him for many years prior to his death.

There has been regrettably little discussion of his writing apart from contemporary reviews. Reginald Hill wrote an essay about him for the first two editions of Twentieth Century Crime and Mystery Writers and when Reg was unavailable to update it, I wrote a new piece for the next two editions. Six years ago, Bob Cornwell invited him to contribute to the CADS questionnaire, but he declined pleasantly, pleading ill-health. So he was a man of mystery in more ways than one. But for anyone who enjoys twisty plots, the work of Martin Russell is well worth investigating.

October 18, 2021

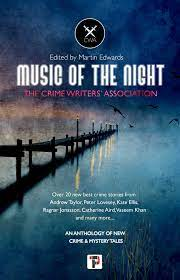

Music of the Night - a new CWA anthology

During the past year I've worked on a wide range of projects. Among them is Music of the Night, a new anthology published by Flame Tree Press under the aegis of the Crime Writers' Association. This follows Vintage Crime, a collection of stories culled from previous CWA anthologies and again published by Flame Tree. They produce very attractive books and I find them a pleasure to work with - they are enthusiastic and (not quite such a common trait among publishers!) very quick to respond.

I've been toying with the idea of a music-related anthology of mystery stories for quite a long time. Music means so much to us that it inspires some wonderful fiction. When I was invited to edit another CWA collection, it seemed like the perfect theme. And CWA members responded with their customary energy and enthusiasm. I was inundated with submissions, and making final choices was far from easy. The toughest part of editing an anthology is to reject stories. It comes with the job, of course, but I hate disappointing people. It's never enjoyable to receive a rejection. But I console myself with the reflection that many if not all of the stories that didn't make the cut will surely surface elsewhere in due course.

We have a nice mix of contributors. So there are four CWA Diamond Dagger winners, including Catherine Aird, Peter Lovesey, and Andrew Taylor, as well as high profile younger authors such as Ragnar Jonasson and Vaseem Khan and writers from overseas such as Art Taylor. And then there are various authors whose names are not yet as well-known. I'm extremely pleased that no fewer than nine of the 26 stories in the book have been written by CWA members whose work has never before featured in a CWA anthology. And yes, I found room for one of my own efforts. Somehow I resisted the temptation to take inspiration from the work of Burt Bacharach (in the past I've produced such stories as 'A House is Not a Home' and 'Twenty Four Hours from Tulsa') and instead wrote a story which relates to Joni Mitchell. It's called 'The Crazy Cries of Love'.

This year sees the 25th anniversary of publication of the first CWA anthology that I edited, Perfectly Criminal. A long time in the hot seat! Suffice to say that I've really enjoyed introducing a very wide range of talented authors to new readers and that I'm optimistic that this latest collection will entertain at least as much as its predecessors.

October 15, 2021

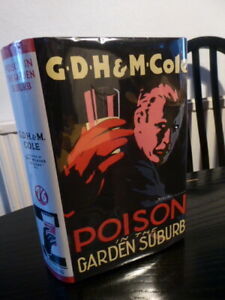

Forgotten Book - Poison in the Garden Suburb

The detective novels of the husband and wife team GDH and Margaret Cole are rather a mixed bag. I have to say that I've been disappointed with quite a number of those I've read. It's always possible, however, that one may drop unlucky with a particular book, or even a number of them, so I thought I'd give the Coles another try. Their early (1929) detective novel Poison in the Garden Suburb received praise from Barzun and Taylor, so it seemed like a good option.

The story gets off to a lively, and occasionally witty, start. People gather at the Literary Institute of Medstead Garden Suburb to listen to a talk by a noted lecturer, but proceedings are interrupted by the collapse and sudden death of a nondescript bourgeois banker called Cayley, whose only claim to fame is that his young wife is extraordinarily beautiful (and not very bright: the authors clearly don't approve of her). The dead man has been poisoned with strychnine and the prime suspect is a young doctor called Shorthouse, whose behaviour is idiotic to put it mildly.

As a result of this drama, we're not told much about the talk itself, but its subject was eugenics. The Coles were leading lights in the Fabian Society (its fictional equivalent features in the novel as the Bureau for Left-Wing Information), which had a considerable enthusiasm for eugenics at one time. I wondered if Rachel Redford, one of the main characters and employed by the Bureau, was to some extent a fictional portrait of Margaret Cole herself. There are some nice bits of social comment in the early part of the book before we get rather bogged down in the murder investigation.

One of the official detectives, a gloomy superintendent, is pleasingly presented, but the key investigator is the Coles' series sleuth Henry Wilson, who at this stage of his career was operating as a private detective prior to returning to duty at Scotland Yard. I felt the story sagged in the middle, and the climactic excitement felt rather underwhelming, especially since I thought the identity of the murderer was fairly obvious from early on in the story (even though the culprit's true character was barely hinted at: I don't think this is a stellar example of fair play, at least in psychological terms). Overall, this is a novel with some very good ingredients made into a passably entertaining story. Nick Fuller reviewed the book a while ago and makes a number of good point as well as including fascinating contemporary reviews.