Martin Edwards's Blog, page 43

May 5, 2023

Forgotten Book - Obelists at Sea

A forgotten book with a difference today, since this week sees a new edition of C. Daly King's Obelists at Sea, published by Otto Penzler's Mysterious Press in its American Mystery Classics series, and with an introduction by me. I'm very glad to say that it's already received a coveted starred review in Booklist.

The review said: '"Ingenious … A satisfyingly complex solution to both crimes; sometimes brilliant and sometimes hilarious applications from psychology; and a 'clue-finder' at mystery’s end―all of this makes for a delightful Golden Age return. With an engrossing introduction by novelist-critic Martin Edwards, who also edits the British Library’s Crime Classics series.' A really good start!

I've always enjoyed Daly King's flights of literary fancy. His writing is sometimes flawed, often a guilty pleasure, always 'different'. I first read this novel many moons ago and before I reread it for the purposes of writing the intro, I thought it the weakest of the three 'Obelist' novels. This was a good example of a situation where I enjoyed the story more the second time around, partly perhaps because my expectations were different.

My writing is very different from Daly King's, but there are occasional nods to him in my Rachel Savernake novels, especially in my use of Clue Finders, a device which he did not invent but of which he demonstrated true mastery. His books are sometimes a bit crazy, generally a lot of fun, and this is a commission from Otto which gave me a great deal of pleasure.

May 2, 2023

A Trip to Remember

I'm back home, reminding myself how to get over jetlag, after a truly exhilarating trip to the United States. I had a packed itinerary and before setting off I was genuinely daunted about how things would go. As it turned out, wildest dreams were exceeded. I returned bearing an Edgar and, at a stop-over for a flight connection in Dublin there was an amazing moment when I learned that I'd received a lifetime achievement award for my short crime fiction (more of which, another day). The chance to meet old friends and make new ones was, after the strange few years we've all had, absolutely wonderful. What's more, I managed not to lose my passport or mess up the complex logistics of the trip, and that counts as a real triumph!

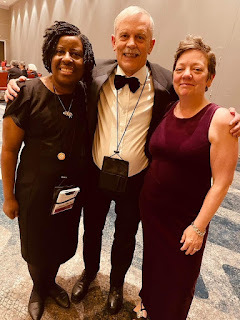

I flew out to Washington DC before catching a train to New York and dashing from my hotel to the pre-Edgars party hosted by Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine. There I had the chance to catch up with Janet Hutchings, Charles Todd and Bill McCormick among others, as well as meeting Michele Slung and Joseph Goodrich for the first time. Then it was another dash back to get changed for the champagne reception for Edgar nominees and to meet my American publicist Jennifer Dee (pictured below with the Edgar) as well as fellow nominees Robert Thorogood and Donna Moore (in the above photo), Jamie Bernthal, and Mary Ann Evans.

The Edgars banquet was lavish and I had the pleasure of sharing a table with Anthony Horowitz (below, with his Edgar), whose A Line to Kill I had, by coincidence, read on the plane trip. He is a terrific entertainer. And then there was an unforgettable repeat of an experience I had at my last Edgars banquet seven years ago, when The Life of Crime was announced as the winner of the Best Crime Non-Fiction Book award. I don't believe in preparing speeches in advance for these things, but you can see my attempt to express my delight on the MWA Youtube channel.

Over the years, not many British authors have received two Edgars and I do feel quite humbled by this recognition. I am proud of The Life of Crime, but it's one thing to believe in yourself and your work, quite another for others to do so. There's no doubt this ranks among the top highlights of my entire writing career.

After a celebratory drink with Jennifer, I dashed off to Otto Penzler's late night party and chatted about book collecting with Larry Gandle and Otto before heading back for the hotel, happy but acutely aware I was due to catch a train at 9 am to return to Washington. I managed to catch it and registered for Malice Domestic before joining Catriona McPherson, Ann Cleeves, Vaseem Khan, and Victoria Dowd for a delightful dinner - on a wet night rather reminiscent of Manchester on a bleak autumn day - see above! There was also the chance to chat with fellow diners Michael Dirda, Gigi Pandian, Jeff Marks, and my holiday companion from Hawaii, Steve Steinbock. Mike Dirda and I had another drink in the hotel before the end of the night and as always it was great fun to exchange ideas with one of the finest literary critics around.

On Saturday morning, there was a panel with fellow Agatha nominee (and ultimate winner) Dianne Vallery and in the afternoon I was on another panel, chaired by James Lincoln Warren and featuring Victoria, Jeff Marks of Crippen & Landru, and Shelly Dickson Carr, grand-daughter of John and one of the most delightful people I know. I was pleased to meet some lovely people for the first time, including Gay Kinman (bottom photo, with Art Taylor), who edited an anthology containing my story 'The Outsider' and Tina de Bellegarde and Carol Pouliot, on whose Sleuths and Sidekicks blog an interview with me will appear shortly. The Agathas banquet was another grand affair and after that there were drinks with Ann, Catriona, and two more of my American friends I haven't seen for years, and who have battled with very serious illness, Tonya Spratt-Williams and Shawn Reilly Simmons. I have thought of them both many times over the frustrating time when I haven't had a chance to see them in person. It was so good not only to chat with them, but also to see how marvellously well they are looking after all they have been through. Tonya, incidentally, gave a brilliant off-the-cuff speech at the banquet, where she was Fan Guest of Honour.

On Sunday, there were conversations with a host of people, including Jeff, Shelly, Shawn, Steve Steinbock, Bruce Coffin, Josh Pachter, Nina Wachsman, and many more. I also enjoyed catching up with Maya Corrigan, who told me how shocked and delighted she'd been to find one of her books mentioned in The Life of Crime. After the traditional Agatha tea, it was all over for another year, but I left with many happy and energising memories of a truly fantastic few days.

You never get the chance to chat to everyone at as much length as you'd wish at these events, but I thoroughly enjoyed the conversations I did have, and the sense of being back among so many friends for whom I have a great deal of affection and regard. And much as I love the awards side of things, that is what counts for so much in the long run.

April 28, 2023

Forgotten Book - The Windy Side of the Law

I'm not sure why I've never got around to reading Sara Woods' detective novels until now. The books were a fixture in the local library when I was growing up. They were published by Collins Crime Club, and because of my enthusiasm for Agatha Christie and Julian Symons, I knew that was a strong brand. But somehow, I was never tempted to try Woods.

This changed when I acquired an inscribed copy of The Windy Side of the Law, which she published in 1965. This is another in her long-running series featuring the London barrister Antony Maitland. And it has a fascinating if not totally original launching point. A man wakes up in a hotel room and realises he has lost his memory. But scrawled in his diary is Maitland's name..

The amnesiac turns out to be a chap called Peter Hammond, who is a friend of Antony's. Good old Antony is keen to help Peter to sort out what has happened to him, but things turn nasty when drugs are found in Peter's possession and even nastier when he finds himself implicated in a case of murder. The complications pile on as it emerges that he was due to marry one woman, but had apparently embarked on a relationship with another.

In his efforts to solve the mystery, Antony acts in a way that I didn't find entirely convincing, taking risks that would terrify most barristers, and sometimes for reasons that I didn't think were sufficiently compelling. Early on, the story becomes thrillerish and although it's a complicated tale, I felt that a key revelation was all too predictable. Not a bad story, then, but not one that entirely fulfils the great promise of the opening. I'd be happy to read more Sara Woods, but on the evidence of this book she strikes me as a competent second rank writer rather than a neglected superstar.

April 26, 2023

I Came By - 2022 film review

I Came By is a recent psychological suspense movie which takes a situation that has become overly familiar in the crime genre and tries to do something relatively fresh with it. The result is a well-made film that shifts viewpoints interestingly and kept me fully engaged despite some flaws. This is partly because the lead actors - Hugh Bonneville, Kelly Macdonald, George Mackay and Percelle Ascott - do a very good job, partly because the script is a cut above the average.

We begin with two young graffiti artists breaking into the homes of rich people and leaving the message 'I Came By'. Their thinking is vaguely and crudely political, and throughout the film, points are made (sometimes very effectively, sometimes feebly) about the misuse of wealth and influence. On the whole, though, the didactic elements don't overwhelm the story, even if sometimes they weaken it.

When one of the lads discovers that a wealthy retired judge (Bonneville, in a very nasty role) is keeping a dark secret in his basement, he is appalled and tries to do something about it. But Bonneville is a mate of Tony Blair, whose photo he keeps in the house, and is known for his 'liberal' views. He's also chummy with the senior local cop. He brushes off accusations in a way that is just about credible, though it might have been presented with greater finesse.

Two more characters in turn try to penetrate the secrets of the cellar, with mixed results. One strong point of the story was that the motivations of the characters is presented with clarity, so that even the ex-judge's weirdness is understandable, if not excusable. This is not by any means a perfect thriller, but it's got enough verve to merit watching.

April 24, 2023

The Daggers - and Zooming Around

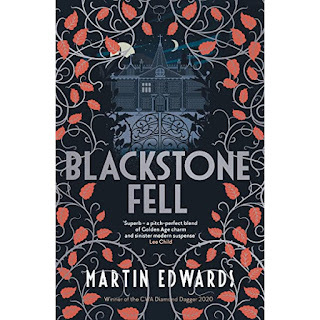

I'm back home, briefly, from the CWA annual conference in York, a great weekend made even more enjoyable by the fact that two of my books appeared on the longlists for the 2023 Daggers. Blackstone Fell is up for the CWA Historical Dagger and The Life of Crime for the CWA Gold Dagger for Non-Fiction. I'm having an incredibly lucky run with the latter book and of course I'm truly gratified by the recognition for my fiction; Blackstone Fell is the fifth of my twenty-two novels to be nominated for an award and such things are genuinely motivating, especially at a time when I'm writing something rather experimental, for which I have no contract; in fact nobody else has even seen it yet....

A busy period of events and trips began last Wednesday with a visit to the Lake District. I was speaking to a book group at the Burn How Hotel in Bowness (above), where by coincidence I once stayed on a research trip. A lovely spot and a great night. There was also time for some sight-seeing at wonderful places like Townend (with its fantastic farmer's library; see the above photo) and Sizergh Castle. The weather was kind and my enthusiasm for writing another novel set in the Lakes was duly fired...

The York conference began with a glitzy reception at which I was asked to give a short talk about the CWA's 70 years of history. I was also able to show members a specially bound edition of The House That Jack Built, by Eileen Dewhurst, commemorating Eileen's long and happy association with the CWA. There were some very good talks and I also enjoyed a river boat trip to Bishopthorpe Palace (see the below photo) on Saturday afternoon. The evening banquet, at the City Museum, was one of the most memorable settings I can recall for a meal. Good to see old friends again and also to meet some newer members.

On Wednesday I'm off for a short but frenetic trip to the US and it's good that crime-related events are now taking place again. One thing we have got used to since the pandemic is the Zoom meeting and I've taken part in several interesting sessions of late. These include a chat with Art Taylor for the CWA's North American chapter and a symposium with fellow nominees for the Edgar award for best critical/biographical book, chaired by Joseph Goodrich. Although you can't beat an in-person event, the fact is that online events mean that you can take part in events that - for travel, cost, or logistical reasons - would have been impossible not so long ago. So a mix of the two is ideal.

April 21, 2023

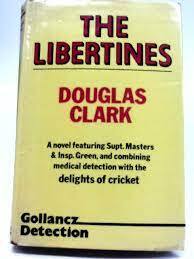

Forgotten Book - The Libertines

Douglas Clark is an author I haven't discussed on this blog before. Until I read his 1978 novel The Libertines, I'd only read one of his books, a very long time ago, and it made little impression on me. I can't even recall the title. But he retains some admirers, mainly because his in-depth knowledge of poisons (gained from working as a copywriter in the pharmaceutical business) informed many of his traditional mysteries featuring the Scotland Yard duo Masters and Green.

The Libertines are an amateur cricket team. Each year they get together for a fortnight's cricket at a farm in a small town in Yorkshire, which I'm pretty sure is a fictional version of Pateley Bridge. The discussion of amateur cricket is authentic and I found it a pleasing feature of the story.

The team members get on well together with one exception. There is a truly odious old guy called Tom Middleton who specialises in antagonising everyone he comes across - I never quite understood why he was so unpleasant. We confidently assume that he will in due course fall victim to murder - but instead another man dies.

There are some nice ingredients in this story. The detail about poison seems highly authentic, as is the description of farm life. I found some of the dialogue oddly stilted and unconvincing while Green's personality is irritating. Perhaps the biggest flaw is that the motive is concealed until the end. So I definitely enjoyed the book, but felt frustrated - because with more work and perhaps stronger editing, it could have been rather better.

April 19, 2023

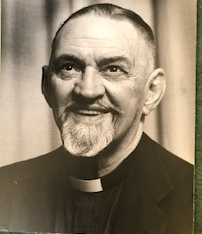

The Quest for Jack Griffiths

I bet most readers of this blog, knowledgeable as they are, will not be overly familiar with the name of the crime writer Jack Griffiths. Yet I first came across his work at an impressionable age and as a result I haven't forgotten him. My introduction to the CWA was via an anthology edited by Herbert Harris and it included (as well as stories by the likes of Edmund Crispin and John Dickson Carr) a tale from south east Asia, 'Two Heads are Better than One' by Jack Griffiths.

In those days the anthologies did not include bios of the contributors - an omission I find close to inexplicable - and although I later came across other anthologies featuring short stories by Jack Griffiths, I knew nothing about him. Fast forward to recent months, and I established that he was a Welshman and a member of the clergy. I decided that I'd like to track down some info about him, and also to include his story 'Black Mamba' in my anthology of Welsh mysteries. Jamie Sturgeon and John Herrington gave me useful details and the British Library, who go to great pains to trace estates so that copyright permissions can be obtained and due payment made, traced Griffiths' daughter, Sian, with whom I've had the pleasure of speaking and corresponding. She also supplied the above photo of her father. He remains little-known by most crime fans, but I'm really pleased to draw his work to the attention of a new readership. And if you're curious, here's what I've learned about him.

Jack Edward Griffiths was born in Blaenclydach insouth Wales in 1902. After studying as a mature student at Aberystwyth University,he was ordained in 1937, became a curate, and married a rector’s daughter in1939. He served in the Territorial Army as a Captain Chaplain and served onhospital ships and overseas during the Second World War. Later, his ministrytook him from Leighton, near Welshpool, to south east Asia; he and his wifesailed to Malaya in 1952 with the apparent intention of staying there long-termand he was Vicar of Penang from 1953-57. In 1960, the family returned to theWelsh Marches, and until retirement in 1975 he was responsible for the three Shropshireparishes of Easthope, Stanton Long, and Shipton, making his home in Easthoperectory, Much Wenlock. He died in nearby Bridgnorth in 1977.Griffiths’ literary specialism was the short story; although he wroteseveral novels over the years, none of them seem to have found a publisher. He was writingfiction for the News Chronicle atleast as early as 1934 and after joining the Crime Writers’ Association (forwhich he served as honorary chaplain), he became a regular contributor to theCWA’s annual anthology, which in the 1960s and 1970s focused mainly on reprintingstories that had already appeared in books and magazines. His interest in crimewas also reflected in a spell as a special constable.

April 15, 2023

Anne Perry R.I.P.

I was sorry to learn of the death last week of the crime novelist Anne Perry. I first met her about 25 years ago, but of course I already knew her by reputation. And unfortunately, where Anne was concerned, mention of her reputation is always accompanied by reference to the murder she committed in her teens, a terrible crime for which she served a sentence in New Zealand.

Anne had come back to Britain and forged a new life under a new name with considerable success - then, with the making of Heavenly Creatures, a film based on the crime, her true identity was suddenly revealed to the world. She was a prolific writer specialising in historical mysteries and she enjoyed huge success in the US in particular. Her main detective, Inspector Pitt, was brought to the TV screens in 1998, but although Keeley Hawes and Peter Egan featured in a quality cast, the show wasn't made into a series.

Anne and I got on well from our first conversation. I found her very interesting and she was consistently generous towards me. She talked to me at length about the experience of being unmasked in that frightening way (a riveting story) but she wasn't self-pitying. We also discussed the writing process and the publishing world in quite a bit of depth and she sent me a draft of her agent's book on the subject of writing a bestseller, in the hope it would encourage me.

We never discussed the old crime itself; I felt that to ask her about it would be grossly intrusive. Over the years she gave me a lot of support, including truly wonderful endorsements for Eve of Destruction and Dancing for the Hangman and an invitation to contribute to two anthologies that she edited - though I must admit that I felt there was a dark irony in the fact that one of them was called Thou Shalt Not Kill. This was a collection of 'Biblical mystery stories' and my contribution was a pretty chilling tale based on the story of Jezebel.

When I was compiling a CWA anthology of history-mysteries, I reached out to Anne and after some discussion about trying a different historical period from the Victorian era in which she specialised, she wrote an absolutely excellent story for me, set in the early twentieth centry. It was called 'Heroes' which made its very first appearance in Past Crimes. In due course, this story won her an Edgar. In fact, it proved to be the only time she won an Edgar, so I like to feel that I repaid her generosity to an extent. On a couple of other occasions, she and I took part in a panels together at venues in London.

One time she and I were part of a small group of crime writers who were invited to an event at Oxford Museum. The photo above originally appeared in the Oxford Mail and it's a favourite of mine. It depicts Anne and me (with a cardboard cutout of Inspector Morse behind us!) along with Michelle Spring, Nora Kelly, Bob Barnard, Andrew Taylor, Keith Miles, Judith Cutler, Kate Charles, and Colin Dexter. Quite a group! It's a summer evening that stands out in my memory, more than twenty years later. After Anne moved to live in the US a few years ago, we lost touch, but I featured her in some depth in The Life of Crime and I tried very hard to write about her in a fair and objective and compassionate rather than prurient way.

I'm aware that not everyone found Anne an easy person and there's no point in pretending otherwise.. I suspect that some people couldn't forgive her for the crime she committed and some, including a couple of friends of mine who also appeared on those panels, found her distant and rather chilly and aloof. Anne could certainly give that impression, but I suspect that it was to a very large extent a technique of self-protection. Beyond a certain point, she was unknowable, but then any author who has thought deeply about characterisation is aware that this is true of many people, perhaps everyone to some degree.

I understand the reservations about Anne but I can only say that my personal experience of her was entirely positive and I've no hesitation in saying that I shall remember her with genuine affection. Yes, she did something appalling and inexcusable in her youth, and it's impossible not to feel profound sorrow for her unfortunate victim. But, thinking about Anne over the years, I've become increasingly convinced that it is right to allow for redemption where the person concerned tries to do the right thing in later life. As far as I am aware, Anne did everything she reasonably could to redeem herself and live a good life. I am glad that I knew her.

April 14, 2023

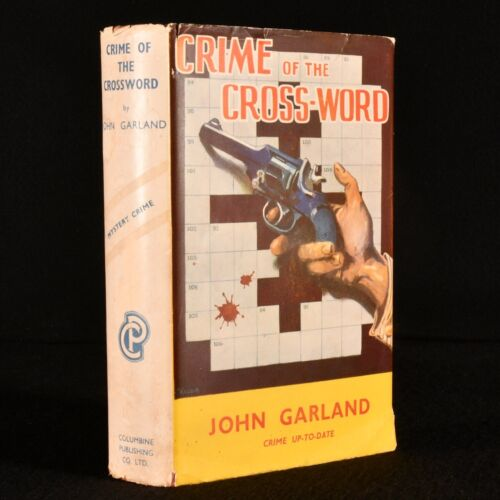

Forgotten Book - Crime of the Crossword

John Garland's Crime of the Crossword, which dates from 1940, is an obscure book. I have Lucy Bratton to thank for drawing my attention to it. I don't know anything about Garland and I wonder if the name was a pseudonym. The dust jacket blurb suggests that he was an established writer, but gives no biographical information and (like many blurbs) needs to be taken with a pinch of salt. Al Hubin's mammoth bibliography indicates that this was a solo effort.

The publisher, Columbine Publishing Ltd of Great Russell Street in London, seems to have been a short-lived concern which went into liquidation a couple of years after this book came out. They don't seem to have made much impact and I imagine they focused on the pulpier kind of fiction. But Garland's writing seems quite professional to me and on a par with that of authors like Gerald Verner or Edwy Searles Brooks. The prose is serviceable rather than enticing and the storyline focuses on incident rather than ingenuity of plot.

One associates crossword puzzles with the more cerebral type of Golden Age whodunit, but although in the early pages I thought Garland was going to set up a whodunit mystery, in fact this is a thriller. There is indeed a crossword (with the solution included at the end of the book, a pleasing touch) but although it provides a clue to a criminal mystery, overall it is just a fun embellishment to a breezy action story.

At the start of the book a businessman called Kerkoff is found dead in mysterious circumstances. A detective in the gentlemanly tradition, Rex Barringer, is engaged by a rather dodgy character who spins an unlikely yarn about Kerkoff's death, but Rex soon realises that his client has a great deal to hide. This is quite an enjoyable yarn and I'm surprised that (apparently) Garland did not continue to write light thrillers in this vein.

April 13, 2023

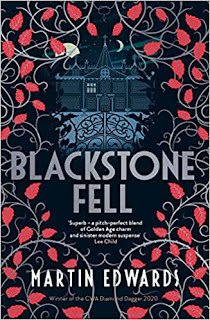

Blackstone Fell in paperback!

Today sees the UK publication in paperback of Blackstone Fell, the third Rachel Savernake novel - with the fourth, Sepulchre Street, due to hit the shelves next month. A writer is never satisfied, but these are both books that I feel particularly happy with, and I wrote quite a few articles about Blackstone Fell at the time the hardback was released, including this one for Booktrail.

I've been gratified by the reviews on the blogosphere - and here's a selection from the print media:

‘RachelSavernake, blessed with wealth and beauty, and Jacob Flint, possessed of a nosefor a good story — who previously appeared in Gallows Court (2018)and Mortmain Hall (2020)— return to investigate the many extraordinary goings-on in Blackstone Fell, acreepy village in darkest Yorkshire. Unexplained disappearances, seances,multiple deaths at a sanatorium patrolled by guard dogs and a murderer on theloose provide a lively and eventful trip back to 1930s Britain as depicted inthe Golden Age mysteries of the period. Martin Edwards celebrates and satirisesthe genre with wit and affection: “Lightning flashed over Hawthorn Cottage as aloud knock came at the door.” He leaves you wanting more.’

Mark Sanderson, The Times

‘For his latest classic mystery, MartinEdwards serves up an engaging mix of ingredients familiar to fans of golden agecrime. A remote village on the Yorkshire moors harbours secrets: two murders,300 years apart, have been committed in the close confines of BlackstoneTower.

Whenan intrepid journalist, one of the rare women reporters of 1930s Fleet Street,also meets an untimely end, it is left to private investigator RachelSavernake, beautiful, rich and fiercely intelligent, to identify the guilty andto exorcise the evil that permeates Blackstone Fell.

Whatgoes on behind the walls of the sanatorium where psychiatric treatment isliable to prove fatal? What can be learned from a spiritualist whoseseances, though fraudulent, provide vital clues?

The plot is intricate but never less than compelling.Martin Edwards holds his own with the best of classic crime.’

Barry Turner, Daily Mail

‘Fabulouslocked room mystery…full of suspense, this entertaining and engaging read is aclassic whodunit.’

My Weekly

‘First-rate and amust-read for this month… The plot is tremendous…the cross-currents brilliant, thewriting pithy, the characters well-realised and the piling up andswitches between possible solutions excellent, with “more loose ends than abowl of spaghetti”. The Cluefinder at the end, the “selection of pointersto the solution of the various mysteries”, serves to demonstrate how farEdwards, the President of the Detection Club, has played fair… Thereis some humour…whilst many academics will recognise this description of aprofessor: “He still thinks he’s in his prime, though he does nothing all daybut rewrite lectures he gave thirty years ago.” Good length. Rachel Savernakemakes an impressive modern Holmes, plus Jacob Flint and Nell Fagan are interestingentrees to Fleet Street with the nature of justice ably to the fore at the end.One to read and enjoy.’

Jeremy Black, The Critic

‘Thethird in the Rachel Savernake investigation is perfect for those who love alocked-room mystery…It has a wonderful golden age of crime feel to it.’

Belfast Telegraph

‘Blackstone Fell is an irresistibleGothic thriller…Edwards’ book keeps you gripped to the very end – you findyourself caring about the characters and their fates. It is intelligentlywritten. The descriptions of Blackstone Fell are vivid and help the reader toappreciate the bleakness of the moors.’

Yorkshire Life

‘As always with thisseries, the period detail is beautifully observed…Rachel remains an enigmaticfigure, but an oddly likeable one too…Blackstone Fell turns out to be anunusually murderous place as the story unfolds: Edwards has a wonderful knackfor propelling the action and lacing it with clues (often subtle ones) alongthe way. This is a thoroughly enjoyable successor to Gallows Court and MortmainHall, ingeniously plotted and racily told…Blackstone Fell is more or less impossible to put down – this isEdwards on the top of his form.’

NigelSimeone, Dorothy L. Sayers Bulletin

‘This is a fascinating novel, with an enigmaticprotagonist and a complex, intriguing plot. Rachel is an intriguing character,incredibly clever and cold-blooded and ruthless to everybody butthe few people she cares about. The books have the authenticity of the author’sdetailed knowledge of the period, plus a darkly clever plot, set in a sinister,brooding landscape. Blackstone Fell is a page turner which I wholeheartedly recommend.’

Carol Westron, Mystery People