Martin Edwards's Blog, page 29

February 26, 2024

Crippen & Landru's 30th birthday

Long before the British Library (and its many followers) started publishing Crime Classics, there was Crippen & Landru, a small press based in the United States which quickly established a splendid reputation for quality of book production matched with high-calibre content. It's a reputation which has been burnished over the years and I'm delighted that this year sees the press's 30th anniversary since it came into being. A remarkable achievement, well worth celebrating.

Crippen & Landru were founded by Douglas G. Greene, who was already well-established as an authority on classic detective fiction. His biography of John Dickson Carr is a model of its kind and he had done some great work in helping to shepherd deserving books back into print. The main focus of his imprint was short stories and this has remained the case through the years. There have been many wonderful single author collections, some of them from contemporary writers, many from notable authors of the past.

When Doug was ready to take a step back from the intensive demands of running Crippen & Landru, Jeffrey Marks took over at the helm (although Doug is still involved). Jeff was the ideal man for the job; he too has published significant books about the genre, including bios of Craig Rice and Anthony Boucher, and the very interesting Atomic Renaissance about female post-war crime writers.

Although I'm based on the other side of the Atlantic, I've had the pleasure of working with Crippen & Landru on a number of occasions, starting with editorial work on The Trinity Cat, a collection of stories by Ellis Peters for the 'Lost Classics' series - was it really 18 years ago? It's always a pleasure to spend in the company of Doug and Jeff and this anniversary is as good a moment as any to thank them for their contribution to the genre. And if you like good mysteries, Crippen & Landru have plenty of books to keep you royally entertained.

February 23, 2024

Forgotten Book - The Murders Near Mapleton

Steve Barge, who blogs as The Puzzle Doctor, has done Golden Age mystery fans a big favour by reviving interest in the books of Brian Flynn and working with Dean Street Press to reissue a good many of the novels. Steve's intros are a model of their kind: concise, informative, and readable. I've read several of the books now and I must say that they contain some excellent ideas, several of which are genuinely ingenious and definitely pleasing.

This is certainly true of The Murders Near Mapleton, which dates from 1929. The story gets off to a tremendous start. The setting of the first chapter, a country house dinner on Christmas Eve, is conventional enough, but there are interesting undercurrents in the dinner table conversation and Flynn wastes no time in getting down to action. By page 34, the master of the house has gone missing, a threatening message has been discovered in a Christmas cracker, two dead bodies have been found (one on a railway track) and one of the deceased, believed by everyone to be a man, turns out to be a woman. Oh, and quite apart from various other minor excitements, somehow the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Austin Kemble, has got involved.

I was impressed by all of this and it's fair to say that, when all is revealed, there are some very clever touches indeed. But - you knew there was a 'but' coming, didn't you? - this book also displays Flynn's characteristic weaknesses. The first of these is that his brilliant amateur detective, Anthony Bathurst, is smug and (in this book more than the others I've read) frankly irritating. One also wonders how Sir Austin got such a plum job - he seems to be so useless as to make Francis Durbridge's Sir Graham Forbes seem like Poirot. Flynn's over-ornate writing style also makes me groan. For instance: 'The realisation flooded his brain with pellucid certainty that once again the clutch of circumstance had summoned him to cross swords with one who was undoubtedly a master criminal.' Steve wonders why Flynn was never elected to the Detection Club; I'm pretty sure the answer is to be found in Dorothy L.Sayers' reviews of two of his 1934 novels - she notes the ingenuity, but flays the prose.

In any elaborate mystery of this type, the author hopes (believe me, I know!) that the reader will be generous in terms of suspending disbelief. Fair enough. However, I was completely baffled by the fact that the transvestism was almost ignored by the detectives, even though inevitably it played a - wholly unconvincing, I'm afraid - part in the story. Sir Austin and the almost equally hapless Inspector Craig hardly mention it and even Anthony seems to take the deception for granted.

As Steve Barge points out, Gladys Mitchell used a very similar idea in a novel also published in 1929 - a notable coincidence, but I agree with him that there's no reason to suspect plagiarism; it's clearly just an idea that occurred to two writers at much the same time, something that happens in reality with quite depressing frequency, perhaps as a reaction to a topical news item. But I do think better use could be made of this idea than Flynn managed. For some time, inspired by the Mitchell novel, I've been wondering if the concept could become an ingredient in a Rachel Savernake mystery and used in a fresh way. Maybe reading this book is the spur I needed!

This novel has been widely discussed on the blogosphere, and although the review on The Grandest Game in the World is pretty crushing, the overall consensus of the reviews is definitely favourable - see, for instance, this one at Murder Ahoy! Despite my reservations, and my sense that this book could have been terrific and didn't live up to its early promise, I did enjoy reading it, something that without Steve's efforts and his advocacy for Brian Flynn simply wouldn't have been possible.

February 21, 2024

The Usual Suspects - 1995 film review

I've mentioned The Usual Suspects a number of times on this blog over the years, although I've never discussed it in any detail. It's a film I enjoyed watching not too long after its release and I decided to take another look at it, to see how well it has held up, twenty-eight years on. The short answer is that it still seems pretty good to me.

Christopher McQuarrie won an Oscar for his screenplay, while Kevin Spacey won for 'best supporting actor'. Both Spacey and the director, Bryan Singer, have had well-documented issues in recent years, but I think it's fair to say that this movie remains a major highlight in their careers. Spacey plays the part of 'Verbal' Kint, a talkative guy with a limp who is a confidence trickster.

Most of the story is told via flashback and it's not always easy to follow. In essence, Kint is explaining to a sceptical cop the circumstances surrounding a fire on a ship in California, which followed a sequence of gangster killings of those on board. Kint and a severely injured Hungarian criminal are the only survivors. The tale unfolds suggests that the person responsible was a master-criminal called Keyser Soze whom nobody can identify.

There's a brilliant twist ending, which I enjoyed again even though I knew it was coming. Really, it's the twist that lifts the film out of the ordinary, even though there are excellent performances by Gabriel Byrne and Pete Postlethwaite as well as Spacey, and a number of good lines and visual images. A very clever idea, nicely executed.

February 19, 2024

Bill Knox, Sue Ward, and The Lazarus Widow

It's hard for me to believe, but twenty-five years have passed since I was commissioned to finish Bill Knox's last novel, The Lazarus Widow, which was published under our joint names way back in 1999. This was the final entry in his long-running and best-known series featuring the Scottish cops Thane and Moss.

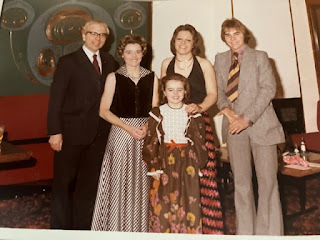

It was an extremely interesting project to undertake and one of the lasting pleasures I've had from it is that I got to know his widow, Myra, and their daughter Sue. Myra died some years ago, but Sue and I are still in regular touch. She has kindly shared a couple of photos from the family album. The above picture dates from her 21st birthday and shows Bill, Myra and the three children. The one below is from the Knoxes' wedding day.

I'm delighted to say that Bill's books are now being made available again. There's a link to the very first Thane and Moss novel here. The big question in my mind with The Lazarus Widow was always: what will the family think about my effort? Sue has kindly shared her own thoughts, which are definitely reassuring from my point of view!

'My mum was with my dad for all her adult life. Theyexperienced many ups and downs and moments of happiness and grief together.

When my father sadly died her practical nature chose tofocus, in part, on the completion of his last book. He had dedicated hisworking life to journalism and it seemed unjust to her that a work of hisshould remain uncompleted. It was the ending or closure that she needed to seea job well done and to do his considerable talent justice.

That was not to be as easy a task as it seemed. The chosenwriter would need a certain style and to be a fan of my dad’s work if the rightfeeling was to be present in the completed novel.

An additional challenge would be the lack of directionaland plot planning evidence left for the brave creature who, once chosen, agreedto such a task. Not a single clue as to the intended ending or chain of eventsto reach that end was available. It was simply not the way he worked.

To read the completed work was a seamless and thrillingexperience. A mixture of job extremely well done and a pleasing feeling ofclosure and completion.'

Susan Ward MBEFebruary 16, 2024

Forgotten Book - The Stylist

The early members of the Detection Club, notably Anthony Berkeley, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Agatha Christie, were all exceptionally interested in the study of true crime cases, and that enthusiasm informed their own work in many ways. I talked about this in some detail in The Golden Age of Murder and it's a subject I plan to return to at a later date. In the meantime, I'm researching widely and I've just read an interesting novel by a Detection Club member of later vintage, Guy Cullingford (whose real name was Constance Taylor) which, in its later stages, reveals the influence of some of the same real life cases that fascinated Berkeley, Sayers, and Christie.

The book in question is The Stylist. It was published in 1968 and was the penultimate Cullingford crime novel (although she also wrote a historical novel a decade or so later). The Stylist is a seriously obscure book. It was never published in paperback or in the United States. I've never read any discussion about it anywhere online, although I have managed to find one contemporary review, from Edmund Crispin, in the Sunday Times. I'd have been unaware of its quality had I not chanced upon an inscribed copy (complete with a photo of the author and a letter from her husband) that caught my fancy.

The jacket describes the book as a 'thriller', but if you're looking for slam-bam action from the get-go, this one is not for you. It's a slow-burn novel, very much character-driven. One ingredient in the story, local government corruption, calls to mind Michael Gilbert's very different The Crack in the Teacup, published two years earlier. Another element is suggestive of yet another very different book, Patricia Highsmith's The Talented Mr Ripley. And the true crime cases which are name-checked late on in the story are those involving Edith Thompson and Alma Rattenbury, which have inspired quite a few crime novels. This one, however, is distinctive.

Laura Chance is a wealthy woman in her fifties married to a dodgy self-made man. She's bored, but when she encounters a new hair stylist, Pierre (an Englishman called Peter) who is half her age, she finds a new interest in life. Slowly, slowly, Cullingford deploys an interesting range of characters in Laura's circle, and in Pierre's, but one can neve be entirely sure where the story is heading. Not much happens for ages, but I was kept gripped by the quality of writing and characterisation. It's subtle and occasionally witty and I really enjoyed it.

And if that isn't enough to encourage you, then I should add that Edmund Crispin, who likened the writing to Trollope, was also enthusiastic. So was Francis Iles, who described it as 'comfortably disturbing throughout...a book not to be missed by the discerning' (with thanks to Arthur Robinson for highlighting the Iles review). What a pity that the book made so little impact - the author must have been very disappointed, because it's clear to me that she took great pains over the writing, and to very good effect.

February 14, 2024

The Secret of Seagull Island - 1982 film review

'Bizarre but watchable' is the verdict of one website on The Secret of Seagull Island, and you couldn't sum this film up much better in three words. I say 'film' but in fact its origin was a five-part Anglo/Italian TV serial and the jumpy editing that seems to have taken place in the process of adaptation contributes to the off-kilter feel of the enterprise. I was drawn to the film mainly because it stars Jeremy Brett, always an interesting actor. Suffice to say that he's not in Sherlock Holmes mode here...

We begin with a brief underwater scene, which ends violently before switching to Barbara Carey (Prunella Ransome) arriving in Italy to search for her missing sister Marianne, who is blind. A chap called Lombardi seems to know more about Marianne that he admits and Barbara enlists the help of a British cultural attache (Nicky Henson) who soon becomes smitten with her.

Barbara's investigation leads her to an encounter with David Malcolm (Jeremy Brett) who owns his own island, lucky chap, which he shares with a female admirer and...someone else. There are quite a few twists and turns, and although I should have seen the major twist coming, the truth is that I didn't.

It's an odd film, and certainly no masterpiece, but it's always fun to watch Jeremy Brett, particularly when he goes into OTT mode. It made a nice change to see Nicky Henson playing a wholly likeable if slightly bumbling character, appropriately called Martin, although I felt Prunella Ransome struggled a bit with a very demanding role. One of the co-writers was Jeremy Burnham, an interesting chap who - uniquely - both acted in and wrote episodes of The Avengers, as well as scripting one episode of Inspector Morse. It rather sums up the eccentric nature of this film that the soundtrack was written by Tony Hatch, better known for writing the theme to Crossroads.

February 12, 2024

Finishing a Novel

Today I'm sending off to my agent the manuscript of my latest novel. This is the fifth in the Rachel Savernake series and it's called Hemlock Bay. I'm pleased with it, but whilst it really is very important for an author to be pleased with a new book, in commercial terms at least, it's essential for one's agent and editor to approve. So - fingers crossed!

I finished the novel before sending it out and also revised it more than once. This is an approach I've evolved over the years and I don't always follow it - it depends on the book. Usually, I want the book to be in the best achievable state before anyone else comments on it. Before I start writing, I'm often asked for a synopsis, but I don't feel tightly bound by synopses - indeed, there's remarkably little resemblance between the synopsis I wrote for Blackstone Fell, for instance, and the novel that was actually published! They are very, very different. One of the reasons for this, of course, is that one gets fresh ideas during the course of writing a book (and that's perhaps also a good reason for taking a fair amount of time to write a novel, not just rushing through it).

But is the novel really finished when it's sent to one's agent? Without getting too metaphysical about it, I'm almost tempted to argue that a novel is never actually finished. This may seem ridiculous, but it's common for agents and editors to make suggestions for changes. Because I'm fairly experienced as a novelist now, changes made at the editorial stage tend to be minor (the main exceptions in my career were I Remember You and Take My Breath Away, both of which underwent radical surgery at the behest of two very good editors, Kate Callaghan and David Shelley respectively).

And even when a book is published, is that really the end of it, for all time? Usually, but not necessarily. What if a new ebook edition gives one the chance to make fresh changes? I'm an inveterate tinkerer (as David Brawn, my wonderful and long-suffering editor for non-fiction books such as The Life of Crime is acutely aware) and given the chance I would always want to make ongoing changes to what I've written - but life is too short to do this extensively. I did, however, make various changes to The Golden Age of Murder for the paperback edition and I was delighted to have the chance to do so.

I suppose all this springs from my belief that writing is in many ways a constant quest for improvement. In trying to improve as a writer, one is also trying to improve the text. If your mind stays receptive to new ideas, then it's almost inevitable that you'll think of better ways to write a passage here, a paragraph there.

What will be the fate of Hemlock Bay? At this stage, it's impossible for me to know for sure. But whatever its shortcomings, I have really loved writing it. And doing the research - in particular, visiting Heysham, shown in the photo above, last June. That was a trip that really fired my imagination, though Hemlock Bay is very different from Heysham, not least in terms of the rising body count...

February 9, 2024

Forgotten Book - Die All, Die Merrily

In recent years I've become a big fan of Leo Bruce's detective novels. His characteristic blend of humour and ingenuity appeals to me, although it was somewhat out of fashion by 1961, when he published Die All, Die Merrily (the title is a quote from Henry IV, Part One), one of 23 novels featuring his amateur detective Carolus Deene. Before I read the Deene books, I tended to assume that they were inferior to his Sergeant Beef novels. But they aren't - at their best, they are truly entertaining.

This book illustrates Bruce's strengths. Deene is urged to get involved with a mystery involving the family of Lady Drumbone, who would nowadays be described as a political activist, and whom Bruce mocks mercilessly. The case concerns a tragedy - the apparent suicide of her nephew. The dead man left behind a tape recording in which he confesses to strangling an unnamed woman - but who was the supposed victim?

It's a teasing set-up and Deene embarks on a long series of interviews, a couple of which are very funny indeed (one interviewee, a woman who is obsessed with featuring in the newspapers, is especially memorable). Bruce was very good on dialogue and it dominates his novels. Of course, one has to suspend disbelief, but the writing is usually engaging enough for the unlikely developments to be a source of pleasure rather than irritation.

The solution to the mystery is cunning and quite complex and I didn't see the key twists coming. Inevitably the characterisation isn't in-depth, and I don't think the culprit's cruelty and ruthlessness - because, as is sometimes the case with Bruce, there is quite a bit of darkness about the crimes - were adequately foreshadowed. For once, however, I didn't mind this, because I had so much fun along the way before all was revealed.

February 7, 2024

Paranoiac - 1963 film review

If you were going to make a Hammer Horror movie, I don't think that a novel written by Josephine Tey would spring to mind as obvious source material. Yet her excellent story Brat Farrar was turned by Jimmy Sangster into Paranoiac, and what is even more surprising is that he made a pretty good job of it. Some Tey fans may hate the over-the-top elements, but the film was definitely more enjoyable than I expected.

Directed by Freddie Francis - who won two Oscars for other work - the film moves at a sprightly pace, opening with a church service in memory of members of the Ashby family. The death of the parents, followed by the subsequent suicide of their oldest child Tony, meant that the remaining children, Eleanor and Simon, have been brought up by their Aunt Harriet.

But they are a troubled group, to put it mildly. Eleanor (Janette Scott) is haunted by Tony's death and Simon (Oliver Reed, at his most crazed and menacing) is trying to have her committed to an asylum so that he can inherit the whole of the family fortune. Eleanor is being 'looked after' by a glamorous French nurse who is having a torrid affair with Simon, while Harriet (Shelia Burrell) has plenty of issues of her own. The family solicitor and trustee (Maurice Denham) fights a losing battle to maintain order, not helped by the villainy of his son and junior partner. Elisabeth Lutyens' music adds to the mood of melancholy and melodrama.

The quality of the cast contributes to the success of the film. There are incestuous sub-texts that would have startled Tey, and although the 'returning prodigal' character is played rather woodenly by Alexander Davion, there are enough plot twists and moments of drama to satisfy most viewers looking for a Sixties horror movie that is better written than most.

February 5, 2024

A Reflection of Fear - 1972 film review

A while back, Scott Herbertson drew my attention to the books of Forbes Rydell, a pen-name for two women, DeLoris Stanton Forbes and Helen B. Rydell. I'm hoping to read and review at least one of their books before long. Forbes (1923-2013) also wrote books under other names - Tobias Wells, DeLoris S. Forbes, and Stanton Forbes. One of the Stanton Forbes novels was Go to Thy Deathbed, which was filmed just over half a century ago as A Reflection of Fear. So when this popped up on Talking Pictures recently, I decided to watch it.

The film has a strong cast, led by Robert Shaw, who plays a writer called Michael. At the start of the film, he has long been estranged from Katherine, who is the mother of his child, Marguerite. Katherine is played by Mary Ure, a very beautiful woman who was married to Shaw but who suffered from alcoholism and died in tragic circumstances in 1975 at the age of just 42. This is, sadly, the last film she made. Marguerite is played by Sondra Locke, whose own life was somewhat troubled, and who in this role plays a character aged 15, even though she was in her late twenties at the time.

It's clear from the start that Marguerite is strange and perhaps disturbed. She lives with Katherine and her grandmother (Signe Hasso) in a remote mansion and spends much of her time talking to her dolls and even amoeba collected from a pond. She has grown up apart from her father but seems to have developed an obsession with him and longs to see him again. When Michael turns up, with his girlfriend (Sally Kellerman) in tow, bad things begin to happen...

This is a strange, unsettling film. The final twist is extraordinary, but not foreshadowed (unlike the majority of the plot developments, which are fairly predictable) and it is introduced in a bizarrely off-hand way, via a telephone message. Apparently the film was severely mangled in the editing process, resulting in various oddities which detract from one's viewing enjoyment. So it's a curiosity rather than a masterpiece. Even so, there's something hypnotic about some of the photography (the director, William A. Fraker, was noted as a cinetographer) which makes it worth a look. And I'd be interested to read the source novel - which presumably follows a much more logical path.