Martin Edwards's Blog, page 274

January 5, 2011

Wallander - The Man Who Smiled: review

The Man Who Smiled is the first episode of Swedish TV's version of Wallander that I've seen starring Rolf Lassgard in the title role. He was the original Wallander, and is arguably closer to Hanning Mankell's character than his successors. Yet at first, I didn't really take to his portrayal of the cop as something of a fat slob who goes to bed with a prostitute and then throws her out of his room.

However, the script was rather well written, and subtleties emerged in the story and characterisation that were not immediately apparent - especially to me, as I've not read the book. Although Wallander's behaviour eventually cost him his relationship with his colleague Maja, Lassgard grew on me as the programme went on.

The story is complicated and unusual, beginning in true Henning Mankell style with an eerie and memorable scene – an old man who is driving his car in the rain, stops when he comes face to face with a mysterious South American figure. Needless to say, he does not survive the encounter.

The ending was fairly downbeat, in a way that is far from traditional, yet seemed believable. There were plenty of vivid moments throughout, and on the whole – even though I still think I prefer Krister Henriksson as Wallander - I felt this was an extremely watchable episode.

January 3, 2011

Alice and Crime

Alice in Wonderland is not only a timeless classic, but also one of my lifelong favourite books. The story has always fascinated me, and not simply because Lewis Carroll grew up not far from where I did, in Cheshire Cat country. On New Year's Eve I watched Tim Burton's film of Alice, and also had chance to reflect on the story once again.

The episodic nature of the story is one of its appeals, and Carroll's inventiveness was so rich that his work has inspired countless others. In the crime field, Night of the Jabberwock by Fredric Brown is a super novel by a terrific writer. I haven't really talked about Brown in this blog, but I rate him very highly.

The late Edward D. Hoch contributed a short story, 'The War in Wonderland', to an anthology that I edited, and it went on to win an award, which gave me a lot of vicarious pleasure. For my own part, I have toyed with the idea of an Alice theme for a crime story, but – so far – the ingredients haven't come together to make a satisfactory whole. Maybe one day.

As for the film, it was an interesting take on the story, with a great cast including Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham Carter. The visual effects were impressive. But it didn't owe too much to the original, and whereas Carroll produced a masterpiece, Burton only managed something that, although watchable and entertaining, felt slightly unsatisfactory. He is a good film-maker, but I still prefer his Mars Attacks!, an uneven but funny movie which I've just watched and enjoyed again.

January 1, 2011

Narrative and The Keys of Marinus

Happy New Year! I thought I'd kick off the blog in 2011 with a few thoughts on narrative inspired by watching a DVD which was a very welcome Christmas present....

The DVD is a very early Doctor Who serial, The Keys of Marinus, which I remember watching when it was first on, and I was eight years old. It stayed in my mind because of the Voord, the strange amphibious creatures who menaced the Doctor (William Hartnell) and his companions. But on watching the show again, it was interesting to see how Terry Nation, the writer who invented the Daleks, tackled narrative.

Each of the 30 minute episodes took the form of an individual quest as the time travellers try to find the fabled Keys of Marinus. The titles of the episodes – The Velvet Web, The Screaming Jungle and so on – were pretty atmospheric in a John Dickson Carr sort of way.

I was impressed by the pace of the episodes, and was kept gripped despite the ricketiness of the sets. Usually, when you watch a TV show from the 60s, it moves much more slowly than modern shows. But here Nation packed his narratives with plot twists, and this helped him to get over the countless improbabilities in his story-line. The verve with which he tells the story illustrates how popular fiction that has pace and imagination can work very well, even if the story and characters have built-in limitations. It was an object lesson in how to tell an exciting tale well.

Finally, my current plan for 2011 is to post on Monday, Wednesday and Friday each week and also add in some extra posts when time permits. Occasionally, over the past few months, work commitments have led to my changing the schedule a bit, and they have also reduced the time I have to look at other blogs. But I hope to get a bit more time in the not too distant future - we'll see!

December 31, 2010

New Year's Eve

In my last post for 2010, I want not only to send my very warmest wishes to my readers for the year ahead, but also to express my thanks for the way in which your kindness and encouragement, manifested in a variety of forms, has helped to carry me through twelve months that have sometimes been more than usually challenging. I am truly grateful.

I also wanted to reflect on some of the good things that have happened this past year. On the writing front, I was thrilled by the response to and reviews of The Serpent Pool, and to have two launches in Hawarden and London, the latter a joint event with Ann Cleeves, was very gratifying. I enjoyed putting together the anthology Original Sins and an excellent press lunch organised by the publishers at a posh restaurant in London. And I'm really pleased about The Hanging Wood – I like to think it is the best Lake District Mystery so far. My trip to the Lakes on my birthday was a real highlight of 2010 - the wonderful weather of July seems a very distant memory now!

Crimefest in Bristol was great fun, including a pub quiz in a team of delightful people and the ordeal that calls itself Criminal Mastermind! I now have two lovely inscribed commemorative pieces of Bristol glassware to remember the last two years' quizzes by; in 2011, I shall be very glad to be in the audience, instead of in the black chair. I met a good many pleasant writers and readers (including readers of this blog) for the first time in 2010, not least at Crimefest, and hope to see at least some of them again next year.

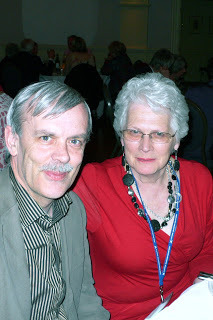

The CWA conference in Abergavenny was great - one of the photos shows my Saturday dinner companion Janet Laurence, and another shows a gathering of crime writers at Abergavenny Castle. For various reasons, I couldn't manage a trip to a US convention this year. However, I paid a fleeting – but very pleasurable – visit to the Harrogate Crime Festival, and missed out on the St Hilda's Conference in Oxford last August for the best of reasons: a cruise in the sun around the magnificent Baltic capitals. But I shall be one of the speakers at St Hilda's next August. I'm looking forward to it already. And next October may – exam results permitting – see both junior Edwardses studying at Oxford, which would be lovely if it happens.

I've given a number of talks, and put on my Victorian murder mystery event a couple of times. And I've read a lot of good books, some old, some new, and most of them (as well as most of the films I've watched) have featured on this blog. Although I've cut down on the number of posts, I'm very glad that the blog continues to be visited very regularly. Above all, I've had the good fortune of much support from friends and family, and many reasons to reflect that the crime writing community really does contain some truly delightful people.

So, all in all, a year with plenty of ups as well as a few downs. But I'm certainly looking forward to 2011 with relish....

December 29, 2010

And Then There Were None - review

I enjoyed Rene Clair's 1945 film version of my favourite Agatha Christie novel, And Then There Were None. The screenplay, by Dudley Nichols – who had previously been the first person to refuse an Oscar – was sound, despite a number of changes from the original.

The set-up is an absolute classic – eight people, along with two staff, are invited to a lonely island by a mysterious stranger. A disembodied gramophone recording accuses those present of having each been guilty of murder. And then, one by one, the guests themselves are murdered...

Apparently, some of the script changes were to fit with the Hays Code of morals on screen that was in force at the time. Christie's story included a child murder committed by one of the guest, and such a crime was deemed beyond the pale. This plot point is an instance, by the way, of Christie's work sometimes being darker than her critics tend to allow.

The big cop-out is the ending, which is much less sinister than the brilliant original (even if the original does require a lengthy written confession, a sign of structural weakness in most detective stories, but not here). However, I thought Clair and his cast did a pretty good job on the film and I was glad to catch up with it at long last. My third 'Christie for Christmas'!

December 27, 2010

Agatha Christie's Marple: The Secret of Chimneys - review

Agatha Christie's Marple this evening gave us The Secret of Chimneys, from a book which dates back to 1925. Jane Marple does not appear in the book, and frankly the story – a cheerfully ludicrous thriller – would be long forgotten if Christie were not the author. I felt compelled to watch, though, to see what the scriptwriter, Paul Rutman – a capable and experienced TV detective drama writer - would make of a very tough challenge.

His approach was to take a few small plot elements and a number of characters (or, at least, their names) from the original but to create an entirely new story, with the scene being set in 1932 before moving into the 1950s, with Miss Marple, in the shape of Julia Mackenzie, improbably invited to Chimneys along with an exotic foreign aristocrat and a woman from 'National Heritage'.

The cast was good, including the reliable Edward Fox, the beautiful Charlotte Salt and the talented Dervla Kirwan. But the story-line was risible and Christie probably turned in her grave at the identity and motive of the culprit. I was certainly amazed, but not in a good way.

I was left wondering what was the object of the exercise. I could see the point of the new TV version of Murder on the Orient Express, even though I've read some comments by purists who disapprove of the changes made to the original, because the focus on justice was – to me – genuinely interesting. But with The Secret of Chimneys, a silly but mildly amusing book from the 1920s just became a silly TV show of 2010. Disappointing, to say the least.

Christmas in Cheshire

I've always celebrated Christmas in Cheshire, but I've never known one as white (or as cold!) as this year's! Here are some photos I took while walking out on the 25th. And I hope the festivities have been going well for the readers of this blog.

December 26, 2010

New books in 2011

I'm looking forward rather eagerly to a number of publications next year. When I first became a published author, I got a real kick out of seeing my manuscript turned into a 'proper book', and I've not lost the thrill of the experience, thank goodness. It really is exhilarating. The Serpent Pool appears in paperback in the UK early in January, and given the extensive and favourable reviews of the hardback edition, I'm hoping that reaction will again be very positive.

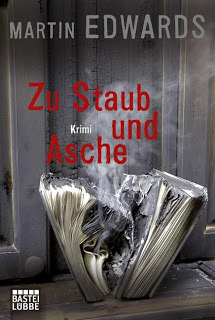

The Hanging Wood will appear, at least in the US, under the Poisoned Press imprint. I'm not yet sure what is likely to happen in the UK. Around the same time, my German publishers will bring out The Serpent Pool. Here is the proposed cover. The title, in translation, is 'To Dust and Ashes'.

Take My Breath Away will be published by Five Star in the US in June, and although the book was written eight years ago, I'm absolutely delighted it's having a fresh life. Of all my novels, it's the one which I think was the most under-rated. Of course, it may be that authors are not the best judges of their own work. But even so...

On the anthology front, there should be a limited collectors' edition of the CWA anthology, Original Sins. And the follow up to that collection, Guilty Consciences, may be out in May. I hope so, as it would mean we could launch it at Crimefest. But there's still some work to be done before we can know for sure....

Agatha Christie's Poirot: Murder on the Orient Express - review

Murder on the Orient Express, starring David Suchet, the latest Agatha Christie's Poirot to hit the TV screen, was my choice for Christmas Day viewing. And I'm glad I watched it, since it was one of the best of all the screen versions of any Christie story. Better, certainly, than the film version of the book starring Albert Finney as Poirot, even though the film is not at all bad.

Why was this version so good? The answer lies in the focus on the precise nature of the motive for the crime and the proper response to it. I guess that most readers of this blog are familiar with the central gimmick, but I'm not going to give it away. However, the key theme of the book – as with And Then There Were None – is the idea of doing justice, and in particular the doing of justice in circumstances where conventional legal systems fail to achieve the 'right' result.

This is a powerful, perhaps eternal, issue, one that is apt to crop up in all societies, at all times. And Christie's willingness to take on such issues, in the context of an elaborately and innovatively plotted classic detective story, is one of the reasons for her enduring success. The screenplay homed in on Poirot's battle with his conscience, and I thought that Suchet's performance was superb.

The supporting cast, including Eileen Atkins and David Morrissey, was very strong without being over-burdened by star names. The script by Stewart Harcourt was first class, creating a consistently sinister atmosphere. Anyone expecting an entirely cosy experience from watching this version will have been surprised. But also, I hope, impressed.

December 24, 2010

Christmas

As Christmas approaches - and as you can see from the photo, it's a white Christmas here in Lymmm, can I sent my very best wishes to all of you who read this blog. Have a great time!

The TV schedules look promising. But how can I choose at 9 pm between Murder on the Orient Express – the new version with David Suchet – and the classic And Then There Were None, which is my all-time favourite Christie? We'll see!

I do plan to review the new Poirot soon in any event. And maybe the older film too, while I'm at it...