Martin Edwards's Blog, page 23

July 15, 2024

CADS 92 - and the TLS

I've been taking my time over CADS 92, the final instalment of a wonderful magazine that Geoff Bradley has been running since July 1985. That's an incredible 39 years of dedication and the result has been something unique, an informal magazine that has gained immensely from its combination of homespun charm yet authoritative comment from a very wide of contributors.

Geoff mentions that I first contributed to CADS 8 and he and I first met at the London Bouchercon, way back in 1990. I've written plenty of article for the magazine since then, and for the final issue I've included a previously unpublished eulogy that Julian Symons wrote for his friend Michael Underwood, a piece that says, in my opinion, a lot of both men. They were very different people, with very different attitudes, but good friends as well as good writers.

There are, as ever, lots of unexpected delights in this issue, including an excellent article by Arthur Robinson about Anthony Berkeley's book reviews, about which he's given me much information over the years, and another by Clint Stacey on the mysteries of Stewart Farrer. Melvyn Barnes supplements our knowledge about Francis Durbridge's collaborative novels and there are many other good things - too many too mention individually - by a host of good writers, from John Curran and Philip Scowcroft to Liz Gilbey and Mike Wilson.

If you're a fan of detective fiction, with a leaning toward the classics, and you don't know CADS, you should try to track down copies before they all vanish from sight. You will be impressed, as I have been. It's been a huge pleasure, each and every time, to receive a copy of CADS and I'm hugely appreciative of all the hard work Geoff has put into it.

What's more, in this final issue, he's even taken the trouble to include a nice review of The Life of Crime. And I'm afraid I can't resist blowing my own trumpet by saying that the book has just had a rave review, in-depth, in the Times Literary Supplement. The book is also featured in a TLS podcast. To receive such a stunning review is definitely a highlight for me and I'm absolutely thrilled.

July 12, 2024

Forgotten Book - Leave and Bequeath

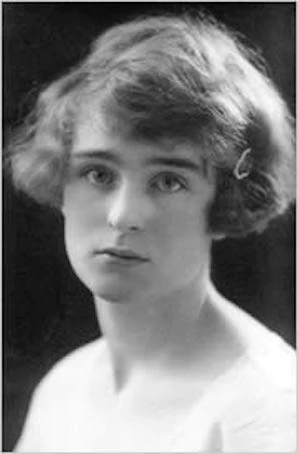

Leave and Bequeath was published in 1943. It was the sixth book published by Winifred E. Watson, but her first attempt at a detective story; some of her other books (which I haven't read) are described as 'rustic bodice-rippers'. After that, although she lived to the ripe old age of 95, dying in 2002, she never published another novel. You might wonder whether the book had some kind of traumatic effect on her literary career, but that wasn't the case. It seems that, quite simply she settled for contented domestic life rather than authorship.

Another curious thing about Winifred. In 1938, she published a novel called Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day. This was a success, published internationally, and a musical version was planned. That didn't happen, but the book was rediscovered by the admirable Persephone Books (on whose website the above photo can be found), much to the elderly author's delight, and turned into a film, albeit after her death, in 2008. The stars were Frances McDormand and Amy Adams and the critics loved it. Truly, the fate of books is unpredictable...

So what do we make of Leave and Bequeath? Well, in many ways it's an archetypal country house mystery. A group of young relatives assemble at the home of aged and cantankerous Aunt Julie, who is one of those rich old people who delights in changing her will and disinheriting her nearest and dearest. So far, so cliched.

However, the characterisation is superior and although for much of the book you wonder when the dramatic action is going to start, the slow build-up leads to an impressive pay-off, with a locked room mystery thrown in. For once, the war plays an integral part in the story. In a sense, therefore, this is a novel which represents a kind of milestone - the transition between the classic country house existence and the harsh realities of modern life. I found, almost to my surprise, that I really cared about the characters. Winifred Watson may have abandoned fiction, but she could write it very well. And I'd like to give special thanks to that very amiable podcaster Sherri Rabinowitz for telling me about this little gem. Much appreciated, Sherri!

July 9, 2024

The Gift - 2015 film review

The Gift begins in a conventional way. A glamorous couple, Simon and Robyn Callem (Jason Bateman and Rebecca Hall) are house-hunting in Los Angeles, having moved from Chicago, where they obviously enjoyed quite a bit of success. He's a thrusting and ambitious businessman, she is a freelance designer, slightly introspective. They find an upmarket new residence and set about putting their own imprint on it. Then they bump into Gordon ('Gordo') Moseley (Joel Edgerton), who says he is an old schoolfriend of Simon's.

Simon seems reluctant to acknowledge their connection, but Gordo leaves a bottle of wine on their doorstep as a present and wangles an invitation to dinner. But there is something slightly 'off' about him, and Robyn's doubts increase when he gives them a more lavish gift of koi carp and then invites them to dinner. Soon, this faintly creepy relationship turns sour.

So far, so predictable. There's nothing unusual about home invasion thrillers. But Edgerton - who wrote and directed the film as well as playing a key role - has various surprises up his sleeve. I anticipated some of them, but not the cleverest twist of all, which comes near the end and creates an unsettling mood of uncertainty about the consequences of the encounters between these three people, all of whom are troubled in their own way.

Spoiler alert - nobody dies in this film, and there is nothing too gruesome on screen. But Edgerton cleverly maintains tension throughout and the result is a subtle and suspenseful film that, even though it traverses familiar ground, does so in a relatively fresh way. The three lead actors are all very good, and so is the script.

Celtic Travels

I'm back home from trips to Ireland (North and the Republic) and then Wales, a thoroughly enjoyable break. I sent off the latest chunk of my work-in-progress to my editor the day before I set off, so at least my literary conscience was clear for the time being - and,as often happens (luckily!) the change of scene helped me while I was thinking out another project...

I've long had an ambition to visit the Giant's Causeway and main purpose of the Irish trip was to fulfil that desire. The Causeway is a fascinating location and - despite a bit of drizzle - it definitely lived up to expectations. We were based in Letterkenny, which has a nice cathedral and a good little museum, while our visits to other places included Donegal (with a boat trip on the lough and sightings of seals and seal pups, plus a pleasing castle and a ruined abbey on the shore), Malin Head, the most northerly part of Ireland, Glenveagh National Park, and the walled city of Derry (where I took a walk along the Peace Bridge - very thought-provoking). It was great to spend a few days in so many evocative places and I found a number of fresh story inspirations.

One place that made a real impression on me was the 'famine village' on the Doagh peninsula. During the potato famine, my great-grandfather fled to England with his family and the story of the horrors that the starving people endured therefore had a special resonance for me. It also made me wonder if now is the time for me to do a bit of research into that side of my family.

No sooner were we back from Ireland than it was off to North Wales for a couple of days, to celebrate my birthday. Even when I was working full-time in the law, I liked to take at least a day off to go on a trip on my birthday and over the years I've been incredibly lucky with the weather. There was a chance to revisit old haunts in Llandudno, Conwy, and Colwyn Bay, but also to discover a few new places in the area. A real highlight was a boat trip around Llandudno Bay - great fun.

July 5, 2024

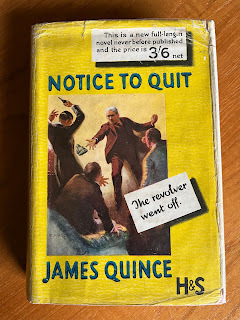

Forgotten Book - Notice to Quit

James Quince was an interesting writer whose career in crime fiction was brief but intriguing. I've previously discussed , the first of his novels, and , the third and best-known. I was lucky enough to add inscribed copies of them to my collection ten years ago, but his second novel, Notice to Quit, proved elusive until recently, when again I was fortunate to snag an inscribed copy at an unexpectedly modest price.

An interesting feature of the book is that it's a hardback, published by Hodder in 1932, which makes a big point (as you can see from my photo) of the fact that its price is 3/6. At that time, I believe the usual price for hardback first editions was 7/6. Hodder brought out a number of cheaper books, including titles by Gavin Holt and D.L. Ames, and I assume this was a response to the economic depression, a way of buoying sales when money was tight.

Whether the scheme worked I don't know for sure, but the very scarcity of Notice to Quit suggest that the print run was small. And it really is scarce - I've not found any online discussion of the book whatsoever, nor anything in any of the usual reference books.

So what's it all about? Quince was an inventive writer, and here,as in The Tin Tree, he tries to do something different. This is a story about an identity switch and I must admit I find such scenarios inherently fascinating (and yes, there are quite a few of them, of various kinds, in my novels).

In a nutshell, Bill Yolland proposes to change identities with his son John. This is an unusual variation on the standard theme, and the aim is to dodge punitive taxation so that the great family home will stay in the Yolland family, given that Bill receives bad news about his health at the start of the book. The early pages are very entertaining, but things then went in a direction that I didn't expect. In many ways, this story is an interesting take on the generation gap, always a fruitful subject for thoughtful authors.

However, there's also a lot of stuff about politics (the Falklands get mentioned more than once!) and a number of unlikely foreign characters, whose appearance in a Golden Age novel always makes me wince. I think Quince could have done something much more interesting with his excellent premise, but we have to judge a book on what the author set out to do. And unfortunately I don't think it works as well as his other novels.

July 3, 2024

The Cater Street Hangman (1998) - TV review

Talking Pictures TV has recently shown The Cater Street Hangman, a 1998 TV movie based on Anne Perry's first novel. It's branded The Inspector Pitt Mysteries and so I presume it was intended as the first of a series, or as a pilot for an intended series. But no more shows seems to have been made. Watching it more than 25 years later, I must say I'm surprised. It's well put together, with a nice twisty mystery and good characters.

It also has the merit of starring Keeley Hawes as Charlotte Ellison, who falls in love with Pitt and proceeds to marry him and feature in the long-running series of novels. Basically, it's a story about a serial killer. Someone is killing young women on the eponymous London street. It becomes clear that Charlotte's family is in the thick of the action and includes at least two of the suspects.

The detection is done by Eoin McCarthy as Pitt. His performance is ok, but perhaps he lacks the star quality of a John Thaw. Certainly Keeley Hawes is the key figure in the story. Her father is played by Peter Egan, a versatile actor who is often very amiable but here plays a rather unpleasant individual. The reliably sinister John Castle is a vicar with a brimstone and treacle approach to preaching, while the consistently enjoyable David Roper and Patsy Rowland make the most of their parts as servants.

The plot is strong - I haven't read the novel, so I can't judge how faithful it is to the source. The period atmosphere is well done, with a sound script by the very experienced T.R. Bowen. I never asked Anne what she thought about the TV version, but she must have been disappointed that it didn't turn into a long-running series, given that the right ingredients seem to have been in place. This is well worth a watch.

July 1, 2024

Daniel Sellers' guest post #2: 'Twists - what makes a twist work?'

'For me,twists are most effective — and impressive — when they’re both ingenious andcredible.

Thereare plenty of twists that don’t meet my ‘gold standard’. I’d argue that anumber of well-known crime stories have ingenious but utterly incredibletwists: Christie’s Murder in Mesopotamia (1936) and Murder onthe Orient Express (1934), for example (though I do love aspects ofboth books, not least their settings). I’d call these overly ingenious twists ‘eyerollers’, and I’m afraid I’d dump a good few Dickson Carrs in with them too. (Apologiesto any fans . . .)

Thenthere are nicely credible twists that are low on ingenuity, but which arestill satisfying. Ruth Rendell was an expert at this kind of utterly compelling,quiet switcheroo, never more so than when she was writing as Barbara Vine. See ADark-Adapted Eye (1986) and the wonderful Asta’s Book (1993). Seealso Agatha Christie’s Five Little Pigs (1943), and P D James’s shortstory, A Very Commonplace Murder (1969). I call these twists ‘quietlysatisfying’.

Then wehave twists that are low in both ingenuity and credibility, and seem to bethere purely for the sake of another surprise. See the bizarre ‘Pip and Emma’reveals in A Murder is Announced (1950). These I call ‘so what?’ twists.

So,which crime stories meet my gold standard by being both ingenious andcredible? I commend three to you, though there are plenty more:

· AgathaChristie’s Witness for the Prosecution (play: 1953), where the twist is gobsmackingand utterly believable as a lot suddenly makes sense;

· DennisLeHane’s Shutter Island (2003), where the twist is ‘extrinsic’,according to the classification I proposed in an earlier post. It’s a stormerof a reveal, not only for the main character but for the reader too. It’s alsovery poignant; and

· DaphneDu Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), where the key twist (two-thirds ofthe way in) is immediately believable and changes everything. Rebecca alsohappens to be one of my favourite novels in any genre.'

Daniel Sellers is author of theLola Harris Glasgow-based mystery series,

publishedby Joffe Books.

June 28, 2024

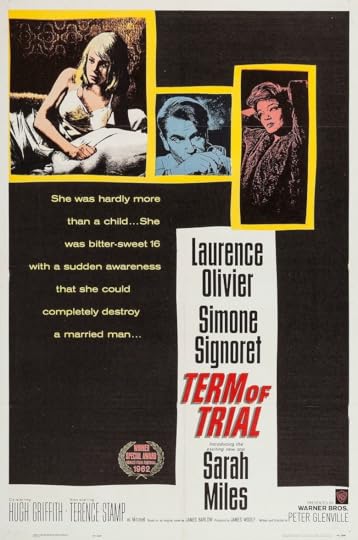

Forgotten Book - Term of Trial

James Barlow was an interesting and capable author whose work occasionally veered into the crime genre. Two of his books were filmed but since his death in 1973, aged just 51, his reputation has faded. I read Term of Trial when working on Lessons in Crime and was struck by the fact that it was published in 1961, just two years after Agatha Christie's well-known public school story Cat Among the Pigeons, but it could hardly have been more different. The novel was written when 'kitchen sink realism' was the flavour of the times and it's very much in that vein. So, yes, the mood is drab, but no, it's not a book to avoid.

Barlow was a very capable writer, although he has a disconcerting habit of making sudden switches of viewpoint within a scene. This is an authorial tic that I don't care for - there are times when it can be justified, but it's often a sign of carelessness. On the whole, however, this is a very well-made novel - and it's set in a secondary modern school. Since my mother taught in such a school for many years, and my oldest friend attended one, I do know quite a bit about what they were like. They've had a very bad press down the years, but often from people who never went inside one - as I did, many times. I don't know if Barlow ever taught in a secondary modern, but my copy is inscribed by him to a 'Fellow Master of the Resistance!', which perhaps suggests that he did.

Graham Wier has recently arrived at a new school, but remains haunted by an act of cowardice during the Second World War. I think most readers of today, including myself, wouldn't regard his behaviour then as cowardly, but times were different then. And that's a point that I kept reminding myself of as I read with some disbelief about Wier's relationship with an attractive female pupil. To say that he was naive is an understatement and despite the air of realism there are some incidents that tested my suspension of disbelief.

However, the quality of the characterisation kept me reading. There is a trial scene towards the end of the book and although the storyline is relentlessly downbeat, I was glad I read it. The book enjoyed success in its day and it was filmed not long after publication with a truly dazzling cast: Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles, Terence Stamp, Hugh Griffith, Roland Culver, Thora Hird, Allan Cuthbertson etc etc. Overall, I'd say the book is a very interesting social document - though in its way, it's as dated as Cat Among the Pigeons.

June 26, 2024

Daniel Sellers guest post: 'Twists, part one: classifying twists'

On the crime writing circuit, one bumps into lots of people, writers and readers, with whom one has the occasional pleasant conversation without necessarily getting the chance to spend a lot of time in their company. A while back I was talking to Daniel Sellers, an interesting writer now based in Scotland whose publishers are the very successful Joffe Books; his series is set in Glasgow and features Lola Harris. A chat with Daniel led to his contributing some thoughts to this blog on the perennially teasing subject of plot twists. Here is the first part; the second will follow in due course:'Mypublisher likes to stress the twistiness of its authors’ crime novels. Straplineson the covers of my first three thrillers declare each to contain a ‘massivetwist’ — so the pressure is on!I love atwist, but have begun to think carefully about how they work — those reveals orinversions that lie in wait for readers.

As astarting point, I think it’s fair to say that twists fall into two classes: thosethat are internal or ‘intrinsic’ to the story; and those that are external, or‘extrinsic’.

Anintrinsic twist surprises or shocks the characters in the story as much as itsurprises the reader. Most traditional (and older) crime stories fall into thiscategory: Christie’s Crooked House (1949) and The Mousetrap (1952)are examples of genuinely astonishing intrinsic twists. The breath-taking twistbecame her speciality. As Robert Barnard pointed out in A Talent to Deceive (1980),‘ . . . she is the despair of later crime writers: because she dared to thinkthe unthinkable there is no trick in the trickster’s book, it seems, that shehasn’t thought of first.’

Anextrinsic twist is a more modern (or should that be post-modern?) development. Thistype of twist isn’t so much a surprise reveal for the characters in the story,as for the reader. Indeed, sometimes the characters in the story already knoweverything, and the reveal is only for readers. An excellent example ofthis is Barbara Vine’s A Fatal Inversion (1987). Another, infilm, is M. Night Shyamalan’s Sixth Sense (1999). Most often thewithholding to achieve this kind of twist is done using the ‘unreliablenarrator’ device (as in Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl (2012)) but this can befrustrating for readers and lead to ‘sameness’ or even a perception of cheating.See Marian Keyes’seloquent take down on Twitter/X last summer.

Unlikethe intrinsic twist, the possibilities of the extrinsic twist seem endless. I’msure we’ll see more twists that lie in how stories are told — some of whichwill thrill us, others which might prove irritating.

I’dargue that Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926) is a fineexample of a crime novel that features an effective intrinsic twist along withthe most famous extrinsic twist of all. Thanks to excellent alibi-making, thecharacters in the story are as surprised as we are when the killer’s identityis revealed (well, maybe the characters aren’t quite as surprised as us!).

What’syour favourite twist in crime fiction?'

June 24, 2024

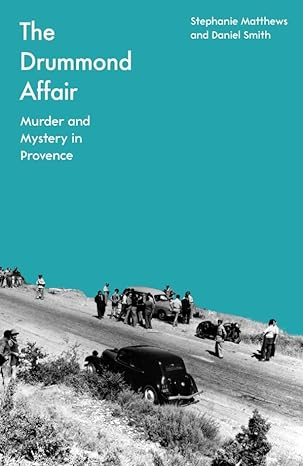

The Drummond Affair by Stephanie Matthews and Daniel Smith

The murder of Sir Jack Drummond and his family in Provence in 1952 was a truly shocking crime that has, so far as most criminologists are concerned, never been adequately explained. The Drummond Affair by Stephanie Matthews and Daniel Smith is a new book about the case and the authors say that, in part, their aim is to rebalance history, not least (and very laudably in my opinion) by placing more emphasis on the victims, rather than on the alleged perpetrator(s).

The authors aim for 'a fundamental re-slanting of the entire narrative'. They say the Drummond murders 'should be one of those shared cultural reference points that everyone knows about, at least vaguely'. That may be putting it a little high, but this is certainly a thought-provoking book about an intriguing mystery.

Sir Jack Drummond was an eminent biochemist, whose work on nutrition and rationing during the Second World War was greatly admired and earned him a knighthood. He later moved to Nottingham to work for Boots. He and his wife Anne and ten-year-old daughter Elizabeth went on holiday to France, but they were gunned down one night in extraordinary circumstances. The investigation owed more to Clouseau than to Poirot and although a local farmer was convicted of the crime, there is much dispute about what really happened. The Guardian has an interesting article about the case here which isn't referenced in the book.

The authors do, however, provide a lot of interesting background information. Perhaps, though, there is an excess of minutiae about Drummond's work in nutrition; I wasn't convinced that all of this cast much light on the crime and some passages felt a little like padding. The authors are rightly critical of the failure of some investigators and criminologists to base their theories on evidence, but there are times when perhaps they fall into the same trap themselves.

For example, there's some speculation about Anne Drummond, e.g. in relation to the extent of her contribution to a book Drummond wrote, and the source of her income, that doesn't really seem to be evidence-based, and there are other instances throughout the text. That said, I think the reality is this: it's often extremely difficult in a true crime book of this kind to avoid speculation and a bit of inspired guesswork. What matters is that the arguments are plausible and the writing style crisp and readable. This book passes both tests and I was glad to read it.