Martin Edwards's Blog, page 218

August 19, 2013

St Hilda's Crime and Mystery Week-end

St Hilda's Crime and Mystery Week-end is a crime conference with a distinctive and delightful personality which makes it very different from other crime-related events. The setting is St Hilda's College, Oxford, and I'm just back from the twentieth conference, which was, if anything, even more enjoyable than usual. The fact that this week-end is not advertised, has no promotional website, and yet has flourished for two decades, speaks for itself. When people do find out about it, and attend, they tend to love it, and go back year after year. There's no clearer sign of success than that.

The theme this year was "The Present and Future of Crime Fiction" and when I was asked to deliver a paper, I thought I would be very crafty and find a neat way to weave a talk about the Golden Age into the over-arching theme. What I hadn't anticipated was that some other writers would have the same idea - and my talk was on Saturday afternoon, while just before lunch P.D. James herself would be speaking about....the Golden Age.

P.D. James was aptly described by Natasha Cooper, the chair of the conference, as the true Queen of Crime and it was wonderful to see that her audience regarded it as a true privilege to be able to listen to her. And so it was. Fortunately for me, there was no overlap between her topics of mine, and one of the more daunting experiences of my public speaking career (yet a real honour) was to see Baroness James herself sitting in the front row to listen to my paper. I did feel a bit nervous, having foolishly said the previous evening that I feel more confident about speaking in public nowadays than I used to, but I managed to get through to the end without drying up completely. The papers are delivered in pairs, so P.D. James spoke along with Frances Fyfield, while I was paired with Peter Robinson - and it was very good to catch up with him again over the week-end.

The other speakers included Andrew Taylor (talking about C.S. Forester), and Val McDermid, while two after dinner speeches were given by Bernard Knight on the Friday, and Cilla Masters on the Saturday. There was also an extremely interesting panel chaired by Ayo Onatade on the future of crime publishing. The attendees included quite a number of notable writers who weren't actually speaking - a few examples include Frances Brody, Ann Granger, Marjorie Eccles, Kate Ellis, and AK Benedict - while I met several writers whose first books are due to appear shortly. As ever with these events, the combination of catching up with old friends and meeting new people was very pleasurable.

Much of the success of St Hilda's is down to continuity and the sterling efforts of the organisers, Kate Charles and Eileen Roberts, and Natasha Cooper, who chairs quite brilliantly in a calm, efficient and extremely generous style that few if any could match. This trio put a huge amount of work into the event, and their reward is simply that they give a lot of people a great time.If you've never attended St Hilda's, I do recommend it very strongly. The dates for next year are 15-17 August 2014.

Published on August 19, 2013 05:30

August 16, 2013

Forgotten Book - Keep It Quiet

Richard Hull, who has featured in my series of Forgotten Books a number of times already, is again the man responsible for today's choice. Keep It Quiet, published in 1935, was a prompt follow-up to his highly successful debut, The Murder of My Aunt. Again, the story-line is unusual, although it's fair to say that, as with so many writers who make a brilliant start, he did not find the second book as straightforward.

Keep It Quiet is set in a gentleman's club in London, and Hull was writing about what he knew, since apparently he was not only a member of such a club, but actually lived there at one time. Biographical details about Hull are fairly scant, mostly confined to bios on the back of a few Penguin editions of his work. I'd be interested to know more about him. He certainly had a sharp sense of humour. The setting gives him plenty of chances to amuse himself and his readers about clubland life. There's quite a funny joke about his own weight, smuggled in to chapter 29, which only makes sense if you know that Hull's real name was Richard Henry Sampson.

A club member appears to have been poisoned by the club cook, and the hapless club secretary decides to embark on a cover-up, with the assistance of a member who happens to be a doctor.This unwise course of action has far-reaching repercussions, and soon it seems that the lives of other members are under threat. The identity of the bad guy (there are no female characters of any significance) is clear from a relatively early stage, and the main question is how the situation will be sorted out, and whether anyone else will die before the end.

There's a neat variation on a familiar solution which introduces the laws of Latvia (of all things) and there's a general quirkiness about the book that works fairly well. The downside, as often with Hull, is that his amusing central idea needed to be stretched out somewhat to result in a full-length novel. Writers like Agatha Christie, who made sure there were plenty of suspects to be studied, structured their books better. But Hull was an engaging writer, and I suspect he was also an engaging companion in real life.

Keep It Quiet is set in a gentleman's club in London, and Hull was writing about what he knew, since apparently he was not only a member of such a club, but actually lived there at one time. Biographical details about Hull are fairly scant, mostly confined to bios on the back of a few Penguin editions of his work. I'd be interested to know more about him. He certainly had a sharp sense of humour. The setting gives him plenty of chances to amuse himself and his readers about clubland life. There's quite a funny joke about his own weight, smuggled in to chapter 29, which only makes sense if you know that Hull's real name was Richard Henry Sampson.

A club member appears to have been poisoned by the club cook, and the hapless club secretary decides to embark on a cover-up, with the assistance of a member who happens to be a doctor.This unwise course of action has far-reaching repercussions, and soon it seems that the lives of other members are under threat. The identity of the bad guy (there are no female characters of any significance) is clear from a relatively early stage, and the main question is how the situation will be sorted out, and whether anyone else will die before the end.

There's a neat variation on a familiar solution which introduces the laws of Latvia (of all things) and there's a general quirkiness about the book that works fairly well. The downside, as often with Hull, is that his amusing central idea needed to be stretched out somewhat to result in a full-length novel. Writers like Agatha Christie, who made sure there were plenty of suspects to be studied, structured their books better. But Hull was an engaging writer, and I suspect he was also an engaging companion in real life.

Published on August 16, 2013 01:57

August 14, 2013

Do Not Cross by Paul Clarke - review

By a series of strange coincidences, this year I've had a number of reminders of the past which I've found these both unexpected and welcome. A library talk in Winsford, for instance, led to my hearing from a contemporary who grew up with many of my friends. An interview that Leigh Russell conducted with me for Mystery People led to my hearing from someone with whom I was at university, but later lost touch. Very enjoyable discussions and catching-up have ensued.

And a few days ago, I received a mysterious parcel from France. It turned out to contain a nicely produced paperback book, a novel called Do Not Cross by Paul Clarke. Paul was a partner in my firm for a good many years, and definitely one of the good guys (not absolutely everyone else qualified for that description, but that's another story!) I used to enjoy chatting to Paul, and he was kind enough to read and comment on a couple of my early Harry Devlin books.

However, a decade or so ago, Paul decided to turn his back on the law, and emigrate to France with his teacher wife Sue. I was sorry to see him go, although I could easily see the attraction of giving up work for a more relaxing way of life. I suppose that in those days, I was personally very driven, not least for financial reasons, and although I dreamed of giving up work to write, I never got close to it. But I'm edging a bit closer now, and the example set by people like Paul is definitely encouraging.

Paul was kind enough to say that our conversations all those years ago had encouraged him to start writing himself, and I'm really delighted about this. So what of Do Not Cross? Well, it's an enjoyable light thriller, set in Liverpool, and the wry tone is set in the very first line: "He was born unlucky; his father died during childbirth."Paul's model is Donald E. Westlake, and Liverpool night life collides with Bin Laden-style terrorism in a lively read. Paul has published his novel both as an ebook and in print, and I hope that reader response encourages him to keep writing. In the meantime, I'm very glad to have read his story, and to have my own signed copy.

And a few days ago, I received a mysterious parcel from France. It turned out to contain a nicely produced paperback book, a novel called Do Not Cross by Paul Clarke. Paul was a partner in my firm for a good many years, and definitely one of the good guys (not absolutely everyone else qualified for that description, but that's another story!) I used to enjoy chatting to Paul, and he was kind enough to read and comment on a couple of my early Harry Devlin books.

However, a decade or so ago, Paul decided to turn his back on the law, and emigrate to France with his teacher wife Sue. I was sorry to see him go, although I could easily see the attraction of giving up work for a more relaxing way of life. I suppose that in those days, I was personally very driven, not least for financial reasons, and although I dreamed of giving up work to write, I never got close to it. But I'm edging a bit closer now, and the example set by people like Paul is definitely encouraging.

Paul was kind enough to say that our conversations all those years ago had encouraged him to start writing himself, and I'm really delighted about this. So what of Do Not Cross? Well, it's an enjoyable light thriller, set in Liverpool, and the wry tone is set in the very first line: "He was born unlucky; his father died during childbirth."Paul's model is Donald E. Westlake, and Liverpool night life collides with Bin Laden-style terrorism in a lively read. Paul has published his novel both as an ebook and in print, and I hope that reader response encourages him to keep writing. In the meantime, I'm very glad to have read his story, and to have my own signed copy.

Published on August 14, 2013 11:34

An evening to remember

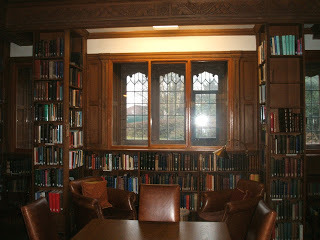

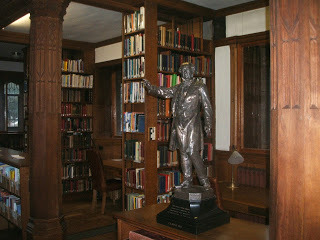

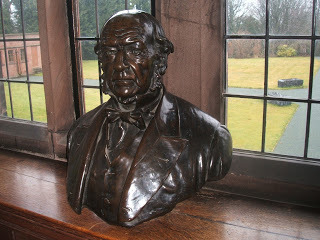

I've mentioned Gladstone's Library, in North Wales, a number of times on this blog, and regular readers will recall that I'm a huge fan of this unique and marvellously atmospheric place, which attracts book lovers and scholars from all over the world - and they can even stay on the premises (in rooms that are extremely pleasant, I may add.)

Yesterday evening saw the official, if slightly belated, UK launch of The Frozen Shroud, and I was especially lucky - not only that the Library hosted the event, as it has done for my last two Lakes books, but also that we were able to hold it in the stunning setting of the library itself. Normally, the library is still being used by researchers and residents in the evening, but because the Gladstone Room, where talks are usually held, is being refurbished, I was given special dispensation to make use of the library itself.

After a reading, a talk about researching the book, and questions, there was a chance to mingle with the audience, always very enjoyable. And a great (and, given the nature of visitors to the library) diverse and international audience it was too - also including Sarah Ward, well known to many of you for her excellent blog Crime Pieces. Sarah has returned to this part of the world after a number of years in Greece and it was good to see her again after our famous 'near miss' in the Harrogate quiz a few weeks ago!

I've been really pleased by reaction to the book so far, with wonderful reviews from The Literary Review and elsewhere. Very good for morale as I set about tackling the next Lake District Mystery.

And I'm delighted to say that I have two further events scheduled at Gladstone's Library in the near future. First, a Victorian murder mystery evening staged as part of their first literary festival, Gladfest (others appearing include Stella Duffy, formerly a writer in residence at the Library) and then I'll be giving my first ever after dinner speech - at the annual conference of the Sherlock Holmes Society of London's annual gathering. Looking forward to both occasions...

Published on August 14, 2013 04:53

August 12, 2013

Town on Trial - film review

I'm rather surprised to find that I don't seem to have mentioned Town on Trial, one of my favourite Fifties British crime films on this blog before. I first saw, and liked, the movie when I was quite young and I've enjoyed it a number of times since. One new thought occurred to me on the latest viewing the other day was that, in essentials, it is rather like a forerunner of Broadchurch. A tough, troubled cop comes to a small town to investigate a murder, and finds several skeletons in the closets of the locals, who close ranks against him.

Suffice to say that I enjoyed Town on Trial just as much as I enjoyed Broadchurch, although of course the latter benefits from the cliffhangers of a serial, and high quality production values. Taking the role in the film equivalent to David Tennant's in the TV show is John Mills, master of the stiff upper lip, as a cop who fancies the American niece of one of the suspects, a local doctor.

A girl is strangled and Mills soon makes himself unpopular, antagonsing the local Casanova and doyen of the tennis club as well as a number of other worthies. One of them, the repressive daughter of a pretty young girl who was friendly with the deceased, is played by Geoffrey Keen, who specialised in gruff hard man roles in film and TV for many years. I remember him best from The Troubleshooters, which is going back a very long time. But he also featured in six James Bond films.

The decisive clue to the killer's identity is one that has always stuck in my mind. I don't know a great deal about the screenplay writers, Ken Hughes and Robert Westerby, but the script is smoothly professional and they both did plenty of film work. Mills is as good as usual, but it's sad that Barbara Bates, his love interest, was evidently a troubled woman who later committed suicide. Elizabeth Seal, the young woman desperate to escape the nest, soon gave up acting, which was a pity, but other cast members including Raymond Huntley and Dandy Nicholls enjoyed successful careers. All in all, an entertaining, well-made film -and recognising that similarity to Broadchurch reminds me how fascinated we are by crime in "closed" communities.

Suffice to say that I enjoyed Town on Trial just as much as I enjoyed Broadchurch, although of course the latter benefits from the cliffhangers of a serial, and high quality production values. Taking the role in the film equivalent to David Tennant's in the TV show is John Mills, master of the stiff upper lip, as a cop who fancies the American niece of one of the suspects, a local doctor.

A girl is strangled and Mills soon makes himself unpopular, antagonsing the local Casanova and doyen of the tennis club as well as a number of other worthies. One of them, the repressive daughter of a pretty young girl who was friendly with the deceased, is played by Geoffrey Keen, who specialised in gruff hard man roles in film and TV for many years. I remember him best from The Troubleshooters, which is going back a very long time. But he also featured in six James Bond films.

The decisive clue to the killer's identity is one that has always stuck in my mind. I don't know a great deal about the screenplay writers, Ken Hughes and Robert Westerby, but the script is smoothly professional and they both did plenty of film work. Mills is as good as usual, but it's sad that Barbara Bates, his love interest, was evidently a troubled woman who later committed suicide. Elizabeth Seal, the young woman desperate to escape the nest, soon gave up acting, which was a pity, but other cast members including Raymond Huntley and Dandy Nicholls enjoyed successful careers. All in all, an entertaining, well-made film -and recognising that similarity to Broadchurch reminds me how fascinated we are by crime in "closed" communities.

Published on August 12, 2013 04:17

Researching a Novel - and Ravenglass

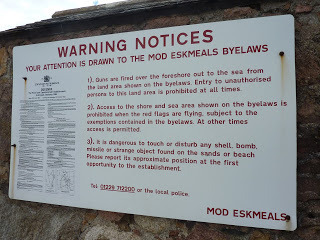

Researching the background of a novel can be hard work on occasion, but it can also be highly pleasurable. I decided recently that I needed to have a re-think about the setting of the new Lake District Mystery, and use a background that I haven't featured before. There were several possibilities, and I decided that I'd start by scouting out the area around Ravenglass on the west coast of Cumbria.

So on Friday, that's exactly what I did. Ravenglass is quite a distance from Cheshire, and I didn't have much time to spare, so it was a whistle-stop tour of an area I've visited briefly in the past. But it was really rewarding, and I'm now pretty settled in thinking that the new story will be based around the west coast. It's a fascinating part of the world, where small coastal resorts lie almost next door to the massive nuclear reactor at Sellafield.

Ravenglass, with its atmospheric estuarine setting, has a narrow gauge railway, on which I travelled on some years ago, and also some Roman remains - the walls of an ancient bath house are tucked away in the trees. I wandered around, trying to figure out how some of the scenes I envisage including in my book could fit into such an area.

Of course, the power of the novelist lies in the ability to make changes to topography. I do this quite a lot, for a number of reasons. First,it helps sometimes to make the story work. Second - and this is often more important - it helps to reinforce the message that I'm writing fiction, not thinly disguised fact. You can take realism too far, and I certainly don't want people living or working in the Lakes to think I am writing about them, their houses or their businesses.

So having researched a location, I invent places to fit into the neighbourhood where the main action of my stories take place. Does this mean the research is a waste of time? Not a bit of it. I now have a better feeling for the coastal areas I visited - including the sand dunes of Drigg - and even if I need to make a few changes before a version of them appears in the novel, the time spent on soakiing up the atmosphere will have been worthwhile. I hope so, anyway...

Published on August 12, 2013 04:02

August 11, 2013

Sebastian Bergman - BBC Four TV review

I watched The Cursed One, the first episode of Sebastian Bergman last night, having missed its original airing last year. This was the second new (to me) series that I've looked at this week, having taken in the first of a two-parter basead on Denise Mina's work, The Field of Blood, a couple of days before. There's a view in some quarters that the quality of British crime shows on TV doesn't compare with that of those from Europe at the moment. I don't agree, but although The Field of Blood certainly has its merits, of the two shows, I found (slightly to my surprise, to be honest) that I was more struck by Sebastian Bergman.

A good deal of this has to do with the terrific performance of Rolf Lassgard as the eponymous crime profiler. At first, Bergman comes across as a deeply troubled and unattractive individual, but the more one learns about him, the more one see the depth in the portrayal. As well as the quality of the acting, the quality of the writing, by Michael Hjorth and Hans Rosenfeldt, is responsible for this. I was impressed.

The opening is striking - a young man, apparently injured, is walking across a football pitch when a sniper shoots him. The victim, it turns out, was leading quite a complicated life, and unravelling it depends not just on some good detective work, but also Bergman's profiling skills. All in all, I thought the plot was handled very well - its trickiness and use of false solutions was reminiscent of Inspector Morse, even if the mood was very different.

Whilst I'm afraid I always find sub-titles a deterrent, I found the story interesting, edgy and twisty enough to keep me gripped from start to finish. Once the culprit was identified, there was still time for a further turn of the screw, as Bergman solved a mystery from his past life. This struck me as genuinely poignant. A very good episode, and I'm glad I have caught up with it at last.

A good deal of this has to do with the terrific performance of Rolf Lassgard as the eponymous crime profiler. At first, Bergman comes across as a deeply troubled and unattractive individual, but the more one learns about him, the more one see the depth in the portrayal. As well as the quality of the acting, the quality of the writing, by Michael Hjorth and Hans Rosenfeldt, is responsible for this. I was impressed.

The opening is striking - a young man, apparently injured, is walking across a football pitch when a sniper shoots him. The victim, it turns out, was leading quite a complicated life, and unravelling it depends not just on some good detective work, but also Bergman's profiling skills. All in all, I thought the plot was handled very well - its trickiness and use of false solutions was reminiscent of Inspector Morse, even if the mood was very different.

Whilst I'm afraid I always find sub-titles a deterrent, I found the story interesting, edgy and twisty enough to keep me gripped from start to finish. Once the culprit was identified, there was still time for a further turn of the screw, as Bergman solved a mystery from his past life. This struck me as genuinely poignant. A very good episode, and I'm glad I have caught up with it at last.

Published on August 11, 2013 07:52

August 9, 2013

Forgotten Book - Found Floating

It's a standing joke with crime writers that a visit to an exotic location should be followed by a book in the same setting, so that the trip can legitimately be treated as tax-deductible. It's also fair to say that writers who travel far and wide often feel inspired to transform their wanderings into fiction. A Mediterranean cruise features in my Forgotten Book for today, and I'm sure that the author, Freeman Wills Crofts, must have been on just such a cruise not long before he wrote the story.

One snag was that his trip, which included a stop in Cadiz, took place before the Spanish Civil War, and by the time Found Floating came out, he needed to explain in a prefatory note that the cruise undertaken by William Carrington and his family also pre-dated the conflict. But you can bet that Crofts enjoyed his cruise. He devotes a whole chapter to an account of the cruise ship! Even allowing for the fact that he did introduce some plot material as well, this "Interlude" as he describes it was a bit much, I felt. On the whole, the story is more about travel than the fairly ingenious murder plan at its heart.

William Carrington is a wealthy businessman, but there is a rift in the family about who should take over. His appointed successor, Mant Carrington, has recently come back to Britain from Australia, and he is not universally popular. He is the main target of an attempted poisoning, and the cruise is intended to aid the recovery of those who were affected, but Mant is not destined to return alive. Inspector French is given the chance to join the ship, and very pleased he is about it too.

The killer's scheme is quite complicated, but I must admit that French's unravelling of it did not keep me gripped. Part of the problem was the very small pool of potential suspects, and the fact that I didn't really care about them. Nor did I think that the killer's motivation was adequately signposted. Crofts wasn't very interested in criminal psychology, and this makes Found Floating a flawed book. He did much better in some of his other novels, but at least I'm sure he had a great time in the Med,!

One snag was that his trip, which included a stop in Cadiz, took place before the Spanish Civil War, and by the time Found Floating came out, he needed to explain in a prefatory note that the cruise undertaken by William Carrington and his family also pre-dated the conflict. But you can bet that Crofts enjoyed his cruise. He devotes a whole chapter to an account of the cruise ship! Even allowing for the fact that he did introduce some plot material as well, this "Interlude" as he describes it was a bit much, I felt. On the whole, the story is more about travel than the fairly ingenious murder plan at its heart.

William Carrington is a wealthy businessman, but there is a rift in the family about who should take over. His appointed successor, Mant Carrington, has recently come back to Britain from Australia, and he is not universally popular. He is the main target of an attempted poisoning, and the cruise is intended to aid the recovery of those who were affected, but Mant is not destined to return alive. Inspector French is given the chance to join the ship, and very pleased he is about it too.

The killer's scheme is quite complicated, but I must admit that French's unravelling of it did not keep me gripped. Part of the problem was the very small pool of potential suspects, and the fact that I didn't really care about them. Nor did I think that the killer's motivation was adequately signposted. Crofts wasn't very interested in criminal psychology, and this makes Found Floating a flawed book. He did much better in some of his other novels, but at least I'm sure he had a great time in the Med,!

Published on August 09, 2013 02:00

August 7, 2013

Dead Woman Walking by Jessica Mann: review

Jessica Mann is a thoughtful and thought-provoking writer whose primary reputation is as a crime novelist. Amongst other things, she's written a study of the "Crime Queens" of the Golden Age, Deadlier than the Male. She's also written outside the genre, and her latest novel, Dead Woman Walking is a reminder of the breadth of her interests.

It's also a peculiarly fascinating book because she's done something unusual and appealing. Just as Agatha Christie, having started her career with A Mysterious Affair at Styles, took Poirot and Hastings back to Styles Court in her excellent and under-estimated novel Curtain, so here Jessica Mann has delved back into her own literary past.

As she explains in a note at the end of the book, the woman who narrates part of the story, Isabel, appearead in her very first novel, A Charitable End. Another major character, the memorably evoked Fidelis Berlin, appeared in an excellent mystery, A Private Inquiry, as well as in two subsequent books which I haven't read as yet. And Jessica is kind enough to say in the note that a suggestion from me inspired her to write a "sort of sequel" to her debut novel, forty years on. Very gratifying from my perspective (especially as she is a writer whose books I enjoyed long before I ever met her), and suffice to say that she's done something unusual and distinctive with that initial idea. The result is a book to savour.

This is a relatively short novel (published by The Cornovia Press, based in Yorkshire) and there are plenty of switches of scenes, as well as (mainly in the early part of the book) switches of period. So we begin with a preamble set in Nazi Germany, move forward to Scotland in 1964, then go to the present day, and so on. The catalyst for the story is the discovery of the body of a woman who disappeared half a century ago, but there is also a dramatic mix of ingredients, ranging from Fidelis' quest for the truth about her own identity to an ingenious method of murder, the abduction of children, and Satanic rituals.

There is a very striking climax, but this is also a novel of ideas, about feminism, family and literature. In addition, I suspect that there may be a number of semi-autobiographical elements. As you would expect with Jessica Mann, it's a very well-written as well as a poignant book, and I'm delighted to have read it.

It's also a peculiarly fascinating book because she's done something unusual and appealing. Just as Agatha Christie, having started her career with A Mysterious Affair at Styles, took Poirot and Hastings back to Styles Court in her excellent and under-estimated novel Curtain, so here Jessica Mann has delved back into her own literary past.

As she explains in a note at the end of the book, the woman who narrates part of the story, Isabel, appearead in her very first novel, A Charitable End. Another major character, the memorably evoked Fidelis Berlin, appeared in an excellent mystery, A Private Inquiry, as well as in two subsequent books which I haven't read as yet. And Jessica is kind enough to say in the note that a suggestion from me inspired her to write a "sort of sequel" to her debut novel, forty years on. Very gratifying from my perspective (especially as she is a writer whose books I enjoyed long before I ever met her), and suffice to say that she's done something unusual and distinctive with that initial idea. The result is a book to savour.

This is a relatively short novel (published by The Cornovia Press, based in Yorkshire) and there are plenty of switches of scenes, as well as (mainly in the early part of the book) switches of period. So we begin with a preamble set in Nazi Germany, move forward to Scotland in 1964, then go to the present day, and so on. The catalyst for the story is the discovery of the body of a woman who disappeared half a century ago, but there is also a dramatic mix of ingredients, ranging from Fidelis' quest for the truth about her own identity to an ingenious method of murder, the abduction of children, and Satanic rituals.

There is a very striking climax, but this is also a novel of ideas, about feminism, family and literature. In addition, I suspect that there may be a number of semi-autobiographical elements. As you would expect with Jessica Mann, it's a very well-written as well as a poignant book, and I'm delighted to have read it.

Published on August 07, 2013 04:01

August 4, 2013

Southcliffe - Channel 4 TV review

Southcliffe, a four part crime series, has just begun on Channel 4 and I made a spur of the moment decision to watch the first episode. I didn't know much about Southcliffe in advance, but the title did make me wonder if it might be a poor man's version of Broadchurch. Far from the truth, as things turned out. Even though the story is set in on the south coast of England, like Broadchurch, the mood and setting are very different.

We know from the first scene that a spree killer is at work. Shades of Michael Ryan in Hungerford and Derrick Bird in Cumbria, as well as all too many other deranged and dangerous people in various parts of the world. But then, in effect, we get a flashback and the rest of the episode shows the build-up to the terrifying events.

A soldier, played by Joe Dempsie, returns to Southcliffe, but it's far from clear that it's a town fit for heroes. One of the locals, known as 'The Commander' (Sean Harris) tries to befriend him, but it is clear from the start that the Commander is a deeply troubled soul. His home life is bleak, his personality disturbing, and his tendency to fantasise about a supposed past in the SAS a very bad sign indeed.

Written by Tony Grisoni, episode one made for raw and, I felt, compelling viewing. I've watched the first episodes of two highly acclaimed imported series, The Returned and Top of the Lake, in recent weeks, but Southcliffe made a greater impact on me than either of those other (no doubt more expensively produced) shows, for all their strengths.

The closing moments were very dark, and I'm expecting more of the same in episode two. But I'll certainly be watching. Comfort viewing it isn't, especially if you work in the tourist office at Faversham in Kent, which provides an intriguing but - so far - cheerless backdrop for the unfolding events. But Southcliffe has got off to an impressive start..

We know from the first scene that a spree killer is at work. Shades of Michael Ryan in Hungerford and Derrick Bird in Cumbria, as well as all too many other deranged and dangerous people in various parts of the world. But then, in effect, we get a flashback and the rest of the episode shows the build-up to the terrifying events.

A soldier, played by Joe Dempsie, returns to Southcliffe, but it's far from clear that it's a town fit for heroes. One of the locals, known as 'The Commander' (Sean Harris) tries to befriend him, but it is clear from the start that the Commander is a deeply troubled soul. His home life is bleak, his personality disturbing, and his tendency to fantasise about a supposed past in the SAS a very bad sign indeed.

Written by Tony Grisoni, episode one made for raw and, I felt, compelling viewing. I've watched the first episodes of two highly acclaimed imported series, The Returned and Top of the Lake, in recent weeks, but Southcliffe made a greater impact on me than either of those other (no doubt more expensively produced) shows, for all their strengths.

The closing moments were very dark, and I'm expecting more of the same in episode two. But I'll certainly be watching. Comfort viewing it isn't, especially if you work in the tourist office at Faversham in Kent, which provides an intriguing but - so far - cheerless backdrop for the unfolding events. But Southcliffe has got off to an impressive start..

Published on August 04, 2013 14:59