Martin Edwards's Blog, page 168

January 25, 2016

Murder at the Manor - and other classic mysteries

I've just received my author copy of Murder at the Manor, another anthology that I've compiled for the British Library. It will be available in early February. Compiling this book has given me the opportunity to bring together another selection of vintage mysteries. I've adopted the same general approach as for Resorting to Murder, Capital Crimes, and Silent Nights. The theme this time is the country house mystery. There are a few (relatively) familiar authors and stories, and a number of less obvious choices, including a little known, but in my view excellent story by Anthony Berkeley.

Over the Christmas break, The Times published a detailed article about the British Library series, after interviewing John Bude's daughter and me, and listed the top ten bestsellers in the series. Even then, a few weeks after its publication, Silent Nights had reached number seven in the list, and the other two anthologies have also sold many more copies than any of the other twenty-odd story collections I've edited. We're very encouraged by this, and several more anthologies are in the works.

The success of the British Library series is being emulated, and sometimes quoted in the publicity material of, other publishers who are, understandably, keen to take part in the current revival of interest in Golden Age fiction. I'm sure there are many people like me who feel that having so many of these old, and previously hard-to-find, books available again at affordable prices, is very good news.

A particular shout-out for Harper Collins, who - even before the BL series took off - have been doing great work in terms of bringing back books like The Floating Admiral and Ask a Policeman. They have more recently been reprinting Francis Durbridge's Paul Temple books, and have launched the very attractively presented Detective Story Club reprints. I hope to cover one of their titles, The Mystery at Stowe by Vernon Loder, before long. Loder is a writer I've heard good things about for years, not least from my friend Nigel Moss, who has written the introduction. Yet I've never come across one of Loder's books, so I was delighted to read it; the book will be on the shelves in the shops in March. Another book in the series, Freeman Wills Crofts' The Ponson Case, with an intro by crime novelist Dolores Gordon-Smith, will also feature here before too long.

Among the estimable smaller presses active in this field are Dean Street Press, whom I've mentioned several times before on this blog. In the coming months, I'll be talking about quite a few of their titles in more detail, The authors they are publishing include Ianthe Jerrold and E.R. Punshon, and I've just received a copy of a book by the highly obscure Robin Forsythe. It's called "Missing or Murdered".

Published on January 25, 2016 01:40

January 22, 2016

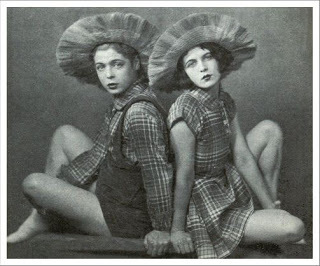

Forgotten Book - Twice Round the Clock

Today I'm featuring another Forgotten Book that came to me from Bob Adey's amazing collection. It's an inscribed copy of Twice Round the Clock, which was published in 1935 by Billie Houston. A striking feature of the front cover of the dust jacket is that it bears not one but two photographs of the author. I must admit I'd never heard of her, but I discovered that Billie was a celebrity in her day, a member of a highly popular music hall act called the Houston Sisters. A bit of research on the internet revealed a performance of theirs on Youtube and this interesting article, which includes the above photo.

This wasn't a ghost-written novel, but one that Billie apparently scribbled away in dressing rooms up and down the country while touring with her sister Renee. She had a long-standing love of the crime story, it seems. And whilst the prose isn't Dickensian, it's not only competent, but rather more engaging than some of the dry stuff that was published at around the same time. This is a readable story, an engaging debut.

It gains something from a storyline that emphasises the rapid passage of time (hinted at by the title.) In a prologue, a body is discovered in a country house, but we then have a long flashback scene in which the tension mounts as it becomes evident that numerous people have good cause to commit a murder. The structure is slightly similar to that of a later book that I much admire, Henry Wade's Lonely Magdalen. The villain of the piece is one of crime fiction's most repellent victims, it has to be said.

This is a lively and unpretentious thriller which I enjoyed reading. It isn't a masterpiece,but it's a good enough first effort to have justified a follow-up. Unfortunately, three years after publication, Houston's husband committed suicide. She gave up life as part of the Houston Sisters - though Renee became quite a well-known actress - and remarried, settling, it would seem, for quiet domesticity. Her obituary in The Times makes no mention of her crime novel, but it's a shame that it's been so completely forgotten.

Published on January 22, 2016 03:45

January 20, 2016

The Edgars

The Golden Age of Murder has been nominated for an Edgar, one of the long-established awards given by the Mystery Writers of America. It's one of five books in the "best critical/biographical" category. Of course, I am delighted. I've been shortlisted for a few awards previously, in my writing and legal careers, and actually managed to win one or two, but of course something as significant as an Edgar nomination comes along rarely if ever in a British writer's life. So the key thing is to savour the moment to the full, which is exactly what I'm doing right now....

I see that, at the Edgar Awards ceremony which is to be held in New York City, that fine writer Walter Mosley is to be acclaimed as a Grand Master. This reminds me that, way back in 1992, when my first novel, All the Lonely People, was one of seven initially shortlisted for the CWA John Creasey Memorial Dagger for best debut crime novel of the year, the award was won (and deservedly so) by Walter for that terrific book, later filmed, Devil in a Blue Dress.

But here's the thing. I didn't even find out that my book was one of the seven nominated books until months after the event. In those days, there was no Twitter, no Facebook, no social media alerting one to such news. The first I heard about it was one day when I was visiting London and I called in at Murder One, the splendid crime bookshop that Maxim Jakubowski used to run in Charing Cross Road. He congratulated me on being shortlisted (Maxim was, and remains, a very well-informed chap, and is nowadays a colleague on the CWA committee), and it came as a complete bolt from the blue. By that time,though, the award ceremony had come and gone. Just shows how things have changed....

Published on January 20, 2016 03:46

January 18, 2016

Before I Go to Sleep - film review

S.J. Watson's bestselling debut novel Before I Go to Sleep must have been a challenging book to adapt for film. Rowan Joffe took on the job a couple of years ago, and I think he made a good job of it, rather better than one or two reviews I've read suggest. And the key to the success of the film, for me, was the small but superlative cast. It was also very sensible (as it usually is) to keep the running time short - slightly over an hour and a half.

Nicole Kidman is Christine, the woman who keeps waking up to the nightmarish reality that she can't remember anything about her life. Each day, she has to be reminded by Colin Firth that he is Ben, her husband, and that some years back, she suffered a terrible accident which caused her to lose her memory. But it soon emerges that it was no accident. She was attacked by someone in a hotel.

She receives daily calls from a doctor, played by Mark Strong, who says he is trying to help her to recover her memory. But it soon becomes clear that he is attracted to her. What exactly are his motives? Can she trust Ben? And what part in her life was played by a friend called Claire (Anne-Marie Duff)?.

I've seen Nicole Kidman excel in a number of different roles; here, she is quite outstanding. Firth and Strong both have a powerful presence on the screen, and the combination works very well. Even though I'd read the book, I found myself gripped from start to finish. Definitely worth watching..

Nicole Kidman is Christine, the woman who keeps waking up to the nightmarish reality that she can't remember anything about her life. Each day, she has to be reminded by Colin Firth that he is Ben, her husband, and that some years back, she suffered a terrible accident which caused her to lose her memory. But it soon emerges that it was no accident. She was attacked by someone in a hotel.

She receives daily calls from a doctor, played by Mark Strong, who says he is trying to help her to recover her memory. But it soon becomes clear that he is attracted to her. What exactly are his motives? Can she trust Ben? And what part in her life was played by a friend called Claire (Anne-Marie Duff)?.

I've seen Nicole Kidman excel in a number of different roles; here, she is quite outstanding. Firth and Strong both have a powerful presence on the screen, and the combination works very well. Even though I'd read the book, I found myself gripped from start to finish. Definitely worth watching..

Published on January 18, 2016 03:24

January 17, 2016

TV detectives - new series

The new year has seen a flurry of new detective series, including the return of a number of old favourites. These include Endeavour, which is written by the excellent Russell Lewis. At the end of the last series, I did wonder how the cliffhanger situation would be resolved. The short answer is that it wasn't addressed very fully at all: Morse spent a bit of time in prison before being freed once the truth was revealed, and then found himself lured back into police work. Not totally satisfactory, but I must say that in other respects the first two stories in the new series have been well-plotted. The error was that end-of-series cliffhanger, which was simply over the top.

Endeavour is a two-hour show in the finest Inspector Morse tradition. Shetland, which returned on Friday, is split into a sequence of two-part one-hour episodes. The new story was, I felt, the strongest so far of those not based on the original novels by Ann Cleeves. A great location can do wonders for a TV show,but it's not everything - above all, you need a good story, and this tale of a young man who meets a grisly fate after travelling to Shetland by sea got the series off to an excellent start.

I'd not seen the first series of The Young Montalbano, but I caught the first episode of the new series. The setting in Sicily is again very attractive, and a lot sunnier than Shetland, while the story was pleasingly convoluted. However, I felt that the tone of the episode was rather uneven, a mix of jokey and serious that jarred a little. There's not much doubt about the tone of Death in Paradise, which has returned with more stories which combine Golden Age style plot devices with an exotic tropical setting. It's very light, undemanding entertainment.

I've stayed with Dickensian, which is a sort of soap opera bringing together lots of characters from Dickens, and held together by an ongoing murder investigation (that of Jacob Marley) conducted by Inspector Bucket. The cast is superb, but the story (20 episodes of 30 minutes each) is starting to drag, while the jaunty background music is an example of too much of a good thing. With this one, I think less would have been more. But what a fine actor Anton Lesser is. He plays Endeavour Morse's prissy boss and, in Dickensian, Fagin, with equal conviction.

And then, away from cop dramas, there's War and Peace. I've never read Leo Tolstoy, and I don't watch many historical dramas, but I do admire Andrew Davies' storytelling skills, and I must say that I am really enjoying this series. Some people tell me that it's dumbed-down, but if that's true, it's dumbed-down very well indeed.

Endeavour is a two-hour show in the finest Inspector Morse tradition. Shetland, which returned on Friday, is split into a sequence of two-part one-hour episodes. The new story was, I felt, the strongest so far of those not based on the original novels by Ann Cleeves. A great location can do wonders for a TV show,but it's not everything - above all, you need a good story, and this tale of a young man who meets a grisly fate after travelling to Shetland by sea got the series off to an excellent start.

I'd not seen the first series of The Young Montalbano, but I caught the first episode of the new series. The setting in Sicily is again very attractive, and a lot sunnier than Shetland, while the story was pleasingly convoluted. However, I felt that the tone of the episode was rather uneven, a mix of jokey and serious that jarred a little. There's not much doubt about the tone of Death in Paradise, which has returned with more stories which combine Golden Age style plot devices with an exotic tropical setting. It's very light, undemanding entertainment.

I've stayed with Dickensian, which is a sort of soap opera bringing together lots of characters from Dickens, and held together by an ongoing murder investigation (that of Jacob Marley) conducted by Inspector Bucket. The cast is superb, but the story (20 episodes of 30 minutes each) is starting to drag, while the jaunty background music is an example of too much of a good thing. With this one, I think less would have been more. But what a fine actor Anton Lesser is. He plays Endeavour Morse's prissy boss and, in Dickensian, Fagin, with equal conviction.

And then, away from cop dramas, there's War and Peace. I've never read Leo Tolstoy, and I don't watch many historical dramas, but I do admire Andrew Davies' storytelling skills, and I must say that I am really enjoying this series. Some people tell me that it's dumbed-down, but if that's true, it's dumbed-down very well indeed.

Published on January 17, 2016 04:32

January 15, 2016

Forgotten Book - She Died a Lady

Bob Adey was a huge fan of John Dickson Carr, and I'm delighted to have acquired a couple of his Carr books with inscriptions. One of these, She Died a Lady, was published under the name Carter Dickson in 1943; the copy is a slim war-time edition, which Carr has inscribed to a woman friend with the comment "more dirty work".

This is a Sir Henry Merrivale story, and it's a very good one. I was delighted with the way Carr pulled the wool over my eyes. With his impossible crime stories, I seldom work out the ingenious m.o. of the killer, which is often too technical for my impractical brain to grasp, but I tend to have better luck in figuring out whodunit. This time, I came up with a nice solution which proved to be hopelessly wrong. And as fellow detective fans know, there are few more satisfying reading experiences than being cleverly fooled by a cunning plot twist or two. And there several good twists in this story.

Other than an epilogue, this story is narrated by a village doctor. Sound familiar ? If not, Carr drops a hint by including a character with the same name as someone in Agatha Christie's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. But is this a clue or a red herring? Suffice to say that I thought Carr pulled off a neat narrative trick here, and although it's one of which Christie would have been proud, it is original as far as I know.

What we have here is a story of a married woman who falls for a young actor. Is her elderly husband blind to what is going on? When the lovers disappear, and seem to have taken part in a suicide pact, the husband is the obvious suspect. But Carr didn't deal in obvious solutions. I felt that he chose an unwisely small pool of potential murderers, but he outsmarted me. I enjoyed this one a lot, and I bet Bob did too.

This is a Sir Henry Merrivale story, and it's a very good one. I was delighted with the way Carr pulled the wool over my eyes. With his impossible crime stories, I seldom work out the ingenious m.o. of the killer, which is often too technical for my impractical brain to grasp, but I tend to have better luck in figuring out whodunit. This time, I came up with a nice solution which proved to be hopelessly wrong. And as fellow detective fans know, there are few more satisfying reading experiences than being cleverly fooled by a cunning plot twist or two. And there several good twists in this story.

Other than an epilogue, this story is narrated by a village doctor. Sound familiar ? If not, Carr drops a hint by including a character with the same name as someone in Agatha Christie's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. But is this a clue or a red herring? Suffice to say that I thought Carr pulled off a neat narrative trick here, and although it's one of which Christie would have been proud, it is original as far as I know.

What we have here is a story of a married woman who falls for a young actor. Is her elderly husband blind to what is going on? When the lovers disappear, and seem to have taken part in a suicide pact, the husband is the obvious suspect. But Carr didn't deal in obvious solutions. I felt that he chose an unwisely small pool of potential murderers, but he outsmarted me. I enjoyed this one a lot, and I bet Bob did too.

Published on January 15, 2016 10:08

Forgotten Book - What Beckoning Ghost?

What Beckoning Ghost? is a 1947 novel by Douglas G. Browne which features his regular detective character Harvey Tuke. Tuke, a senior official in the Department of Public Prosecutions, is invited along with his wife to a dinner party hosted by a couple called the Reaveleys. The host and hostess are connected with strange stories about the sighting of a ghost in Hyde Park, and shortly before the dinner party takes place, a homeless man who has seen the phantom is found dead in the Serpentine.

The dinner party is a tortured affair, with palpable tensions between several of the guests. Although Tuke learns more about the supposed ghost, the evening ends chaotically when Mrs Reaveley flounces out of her own party. Not long after that, she too is found dead - once again, drowned in the Serpentine. Has she committed suicide or been murdered? And what does the ghost of Hyde Park have to do with it?

This novel, rich in London atmosphere, is unusually structured, with several lengthy set-pieces - the dinner party, the inquest on the dead woman, and an underground chase. There are several nice touches, although one particular red herring is never explained, which I found irritating (or did I just miss the explanation? You never know....). Overall, though, this was a book that I really enjoyed.

Browne was a capable writer with a strong interest in true crime. He co-wrote the biography of the famous pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury, and part of the murder plot in this book is drawn from a real life precedent. This is a novel which was much debated by Detection Club members when they were deciding whether or not Browne should be elected to membership. The full story is told in the CADS Supplement Was Corinne's Murder Clued?, by Curtis Evans. Browne was indeed elected to membership. and I'd say deservedly so.

My copy of this book, which has a nice map on the endpapers of the London setting, belonged to Browne himself, and it includes a few tantalising margin notes made by him. The British Library's own copy of the book also has the map. But otherwise identical apparent first editions owned by two leading collectors who are friends of mine do not have the map. It's a bibliographic mystery, to which we don't have the solution. At all events, Browne was a writer who interests me, and I'll be writing again about him in the future. .

The dinner party is a tortured affair, with palpable tensions between several of the guests. Although Tuke learns more about the supposed ghost, the evening ends chaotically when Mrs Reaveley flounces out of her own party. Not long after that, she too is found dead - once again, drowned in the Serpentine. Has she committed suicide or been murdered? And what does the ghost of Hyde Park have to do with it?

This novel, rich in London atmosphere, is unusually structured, with several lengthy set-pieces - the dinner party, the inquest on the dead woman, and an underground chase. There are several nice touches, although one particular red herring is never explained, which I found irritating (or did I just miss the explanation? You never know....). Overall, though, this was a book that I really enjoyed.

Browne was a capable writer with a strong interest in true crime. He co-wrote the biography of the famous pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury, and part of the murder plot in this book is drawn from a real life precedent. This is a novel which was much debated by Detection Club members when they were deciding whether or not Browne should be elected to membership. The full story is told in the CADS Supplement Was Corinne's Murder Clued?, by Curtis Evans. Browne was indeed elected to membership. and I'd say deservedly so.

My copy of this book, which has a nice map on the endpapers of the London setting, belonged to Browne himself, and it includes a few tantalising margin notes made by him. The British Library's own copy of the book also has the map. But otherwise identical apparent first editions owned by two leading collectors who are friends of mine do not have the map. It's a bibliographic mystery, to which we don't have the solution. At all events, Browne was a writer who interests me, and I'll be writing again about him in the future. .

Published on January 15, 2016 02:37

January 13, 2016

James Ellroy by Steven Powell

Last summer, I was invited to speak at a conference at Liverpool University which focused on the work of the American crime writer, James Ellroy. One of the reasons I accepted was that, in my early days as a crime novelist, I found myself reading Ellroy's novels, and thinking about his approach to story-telling. Not because I wanted to emulate his style, but because I believe it's helpful for a writer to absorb a whole range of influences rather than just a few. He is a controversial character, and some of his novels seem to me to be much better than others, but he and his work are thought-provoking, no question about that.

The conference was organised by Steven Powell, a researcher at Liverpool University, who has now written a book about Ellroy, sub-titled Demon Dog of Crime Fiction, and published by Palgrave Macmillan in their Crime Files series. Steven has previously been responsible for a wide-ranging collection of essays in the same series, 100 American Crime Writers, which I found readable and enjoyable, as well as Conversations with James Ellroy, which I have yet to read.

He makes the valid point that critics have often struggled to distinguish between Ellroy's work and his persona, and notes that Ellroy has managed to establish himself as "a character within the history of the genre". A pretty major character, it's fair to say. And I rather like the quote from Ellroy that ends the book: "I'm just James Ellroy, the self-promoting Demon Dog...You call it swagger. I call it joie de vivre.". Steven Powell's ability to recognise that joie de vivre is one of the key strengths of this book.

The book began life as a thesis, and this is a sign of the times. Not so long ago, few academics were interested in writing about crime fiction. Now there is a flood of academic texts about the genre. Some are excellent, but some of them are not exactly riveting, to put it mildly. One or two authors seem to prefer pedantry to conveying a love of the books, never mind a sense of joie de vivre. One of the things I like about Steven Powell's work is that he doesn't fall into this trap. He writes in a readable way, wears his learning lightly, and puts his discussions with Ellroy to good use. The result is scholarly, but not dull, and for me, the absence of page after page of footnotes was a definite plus (there is an extensive bibliography, which is useful.) I'm not an expert on theses, but the book doesn't seem to me to read like one, and that is a Good Thing. If you are interested in studying Ellroy, this thoughtful if not inexpensive book will prove a valuable and important resource..

The conference was organised by Steven Powell, a researcher at Liverpool University, who has now written a book about Ellroy, sub-titled Demon Dog of Crime Fiction, and published by Palgrave Macmillan in their Crime Files series. Steven has previously been responsible for a wide-ranging collection of essays in the same series, 100 American Crime Writers, which I found readable and enjoyable, as well as Conversations with James Ellroy, which I have yet to read.

He makes the valid point that critics have often struggled to distinguish between Ellroy's work and his persona, and notes that Ellroy has managed to establish himself as "a character within the history of the genre". A pretty major character, it's fair to say. And I rather like the quote from Ellroy that ends the book: "I'm just James Ellroy, the self-promoting Demon Dog...You call it swagger. I call it joie de vivre.". Steven Powell's ability to recognise that joie de vivre is one of the key strengths of this book.

The book began life as a thesis, and this is a sign of the times. Not so long ago, few academics were interested in writing about crime fiction. Now there is a flood of academic texts about the genre. Some are excellent, but some of them are not exactly riveting, to put it mildly. One or two authors seem to prefer pedantry to conveying a love of the books, never mind a sense of joie de vivre. One of the things I like about Steven Powell's work is that he doesn't fall into this trap. He writes in a readable way, wears his learning lightly, and puts his discussions with Ellroy to good use. The result is scholarly, but not dull, and for me, the absence of page after page of footnotes was a definite plus (there is an extensive bibliography, which is useful.) I'm not an expert on theses, but the book doesn't seem to me to read like one, and that is a Good Thing. If you are interested in studying Ellroy, this thoughtful if not inexpensive book will prove a valuable and important resource..

Published on January 13, 2016 05:00

January 11, 2016

Keeping Rosy - film review

Keeping Rosy is a 2014 film directed and co-written by Steve Reeves which tells a story of an accidental killing, and the unforeseen and dramatic consequences of an attempt to cover it up. It is, in its essentials, a story not dissimilar to the psychological studies of murder dating back to the Twenties and Thirties - I'm thinking of books like Payment Deferred, the bleak and powerful short early novel by C.S. Forester.

Keeping Rosy is, like Forester's book, short, snappy,and doom-laden. It is, again like Forester's, set in London - not in a depressing part of the suburbs, but in a (some might say, equally depressing) posh new high-rise apartment block. Maxine Peake lives a rather lonely life there. She's a driven career woman, who is evidently jealous of a colleague who brings a new baby into work. Things go from bad to worse when a promotion she thought was in the bag proves not to be forthcoming.

She walks out on the job, threatening to claim constructive dismissal (often a rash move, as most employment lawyers will tell you) and erupts when she finds that her cleaning lady is smoking while she works. From there, things turn rather nasty, and there's a fascinating plot twist quite early on which explains the film's enigmatic title, and which lifts it out of the ordinary run of thrillers of this kind.

Peake is a powerful and versatile actor whose portrayal of a woman on the verge of disintegration is very watchable. It is weakened, however, by the fact that she presents her character as so repellent. Although we see increasing touches of humanity in her as the story progresses, I think the film would have been more compelling if some of those touches had been evident early on. But overall, this is a well-made film which makes good use of its location, and doesn't outstay its welcome. Definitely worth a watch.

Keeping Rosy is, like Forester's book, short, snappy,and doom-laden. It is, again like Forester's, set in London - not in a depressing part of the suburbs, but in a (some might say, equally depressing) posh new high-rise apartment block. Maxine Peake lives a rather lonely life there. She's a driven career woman, who is evidently jealous of a colleague who brings a new baby into work. Things go from bad to worse when a promotion she thought was in the bag proves not to be forthcoming.

She walks out on the job, threatening to claim constructive dismissal (often a rash move, as most employment lawyers will tell you) and erupts when she finds that her cleaning lady is smoking while she works. From there, things turn rather nasty, and there's a fascinating plot twist quite early on which explains the film's enigmatic title, and which lifts it out of the ordinary run of thrillers of this kind.

Peake is a powerful and versatile actor whose portrayal of a woman on the verge of disintegration is very watchable. It is weakened, however, by the fact that she presents her character as so repellent. Although we see increasing touches of humanity in her as the story progresses, I think the film would have been more compelling if some of those touches had been evident early on. But overall, this is a well-made film which makes good use of its location, and doesn't outstay its welcome. Definitely worth a watch.

Published on January 11, 2016 01:20

January 8, 2016

Forgotten Book - Case for Three Detectives

Time for another Forgotten Book from the magnificent (and massive) collection gathered together by the late Bob Adey. This time it's the first detective novel to appear under the name of Leo Bruce. Case for Three Detectives was published in 1936, and introduced a very appealing detective, Sergeant Beef, who proceeded to enjoy a career extending well into the Fifties.

My copy was once owned by Dennis Wheatley, the then famous thriller writer, who evidently had a formidable library, and it bears his bookplate, as well as a personal inscription from Bruce to Wheatley. The connections with Bob, Bruce, and Wheatley make this a favourite in my own collection.

Now to the story -is it any good? Yes, most definitely yes! It's a story with strong elements of parody, but it stands up very well to the test of time. I've written at some length, for CADS, about a slightly similar parodic novel, Gory Knight, by Margaret Rivers Larminie and Jane Langslow, but much as I enjoyed that book, Bruce's novel is clearly superior.

It's a locked room mystery, and the puzzle is a good one. So good that, although Beef is sent to investigate, his detective role is rather usurped by thinly disguised versions of Wimsey, Poirot, and Father Brown. The comedy is very nicely done, and the plot zig-zags around very pleasingly. I enjoyed it enormously. Leo Bruce, by the way, was a pseudonym for Rupert Croft-Crooke, a prolific writer who had an extremely interesting and colourful life. I look forward to writing about him again in future.

My copy was once owned by Dennis Wheatley, the then famous thriller writer, who evidently had a formidable library, and it bears his bookplate, as well as a personal inscription from Bruce to Wheatley. The connections with Bob, Bruce, and Wheatley make this a favourite in my own collection.

Now to the story -is it any good? Yes, most definitely yes! It's a story with strong elements of parody, but it stands up very well to the test of time. I've written at some length, for CADS, about a slightly similar parodic novel, Gory Knight, by Margaret Rivers Larminie and Jane Langslow, but much as I enjoyed that book, Bruce's novel is clearly superior.

It's a locked room mystery, and the puzzle is a good one. So good that, although Beef is sent to investigate, his detective role is rather usurped by thinly disguised versions of Wimsey, Poirot, and Father Brown. The comedy is very nicely done, and the plot zig-zags around very pleasingly. I enjoyed it enormously. Leo Bruce, by the way, was a pseudonym for Rupert Croft-Crooke, a prolific writer who had an extremely interesting and colourful life. I look forward to writing about him again in future.

Published on January 08, 2016 03:52