Martin Edwards's Blog, page 140

July 24, 2017

Harrogate Reflections

I arrived home yesterday afternoon from Harrogate after four fun-filled days at the Theakston's Old Peculier Crime Writing Festival. So fun-filled, in fact, that I fear Friday's Forgotten Book was indeed forgotten! Never mind, it will return this week...

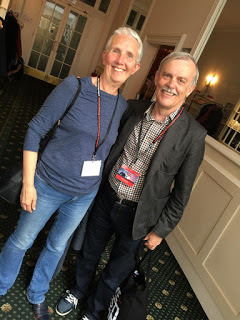

I arrived home yesterday afternoon from Harrogate after four fun-filled days at the Theakston's Old Peculier Crime Writing Festival. So fun-filled, in fact, that I fear Friday's Forgotten Book was indeed forgotten! Never mind, it will return this week...This year I spent more time than usual on writing business, as Harrogate offers a great opportunity to meet up with one's agent and publishers, and so on. But there was still a chance to catch up with friends such as Ann Cleeves and Ali Karim (who took the photo of me with Ann). I also met a good many readers - not least several from the Lake District and my home turf in Cheshire.

I've been on panels at Harrogate in the past, but this year for the first time I was asked to chair a panel - Double Indemnity: the theme was not the James M. Cain novel of that name, but rather lawyers who have become crime writers. Denise Mina (never actually a lawyer, but she did attend Glasgow Law School), Alafair Burke, Steve Cavanagh and Matthew Hall proved to be excellent panellists, and the discussion flowed nicely.

In the signing tent after the panel, I was pleased to meet not only a London crime editor who hails from my home village of Lymm but also a mutual friend of a great pal of mine from long ago student days. A little later I met up with the delightful Roz Dudley, whom I first met when she was performing in one of Joy Swift's brilliant murder mystery weekends (playing the part of a psychopathic serial killer, I should add). And it was good to have a chat with Vera herself, Brenda Blethyn. These unexpected encounters really are part of the pleasure of conventions.

I was invited to several publishers' parties, and these provide an opportunity to catch up with people in the writing business whom one might see only once in a blue moon if one is not London-based. As the wine flowed, there were plenty of fascinating conversations. The northern chapter of the CWA also had an informal get together with CWA colleagues from other parts of the country, and pleasingly the turn-out exceeded our most optimistic expectations.

One of the parties was hosted by Harper Collins, and they'd organised an exhibition of correspondence between Agatha Christie and Billy Collins that I found both interesting and informative. Of my various enjoyable get togethers, one was with a rare book dealer who told me about a notable discovery of his which I hope to talk about more in a future blog post.

All in all, a great weekend. The weather wasn't as kind as usual, with a mini-monsoon on Saturday. But even so, the clouds had a silver lining. Following encouragement from an American editor, I had a bit of time to myself to think out a new short story, featuring a new detective character who might just investigate further cases in due course. I even wrote the first few lines last night..

.

Published on July 24, 2017 03:43

July 20, 2017

Grasmere and the Lake District Mysteries

I've not said much on this blog lately about the Lake District Mysteries. But if you're thinking that my attention has shifted away from them, as a result of my focus on The Golden Age of Murder and The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books, nothing could be further from the truth. My hope has always been that the work I do on classic fiction will have a beneficial impact on my contemporary work, and there are signs that this is what's happening. The latest of those signs is that Amazon have again included The Coffin Trail in their summer promotion. You can get the Kindle version for just 99 pence. If you haven't sampled the series before, I do hope you'll be tempted.

I've not said much on this blog lately about the Lake District Mysteries. But if you're thinking that my attention has shifted away from them, as a result of my focus on The Golden Age of Murder and The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books, nothing could be further from the truth. My hope has always been that the work I do on classic fiction will have a beneficial impact on my contemporary work, and there are signs that this is what's happening. The latest of those signs is that Amazon have again included The Coffin Trail in their summer promotion. You can get the Kindle version for just 99 pence. If you haven't sampled the series before, I do hope you'll be tempted. As it happens, I'm just back from a brief but pleasurable trip to the Lakes. It was a dual purpose visit. First, I was invited to talk to a group of visiting Americans. They were members of a party led by Kathy Ackley and Nicky Godfrey-Evans, whom I've known for a number of years, and they were a great group. A special bonus for me was that among them were those terrific crime writers Charles and Caroline Todd. In recent years, the Todds happen to have shared some happy moments with me at awards ceremonies both here and in the US, and it was great to spend time with them again - not forgetting Linda and DeAnna. A fun evening..

As it happens, I'm just back from a brief but pleasurable trip to the Lakes. It was a dual purpose visit. First, I was invited to talk to a group of visiting Americans. They were members of a party led by Kathy Ackley and Nicky Godfrey-Evans, whom I've known for a number of years, and they were a great group. A special bonus for me was that among them were those terrific crime writers Charles and Caroline Todd. In recent years, the Todds happen to have shared some happy moments with me at awards ceremonies both here and in the US, and it was great to spend time with them again - not forgetting Linda and DeAnna. A fun evening.. The location of the get-together was Grasmere, a village as charming in reality as its reputation suggests. Each of the Lake District Mysteries is set in a different part of the National Park, but I've not yet sent Hannah and Daniel to Grasmere, partly because it seemed a bit of an obvious step, and I wanted to explore one or two less familiar locations. But I do like Grasmere very much, and it may be time that it featured in one of my books. Meanwhile, I was very glad to sign books in Sam Read, the lovely local bookshop. What I think may be happening in quite a few cases, by the way, is that readers who sample my books (and those by others) as ebooks are starting to buy traditional print copies in the shops. Several people have told me that they've done this, and it does seem interesting that perhaps more of a crossover may develop between online and actual book retailing than has been thought likely in the past.

The location of the get-together was Grasmere, a village as charming in reality as its reputation suggests. Each of the Lake District Mysteries is set in a different part of the National Park, but I've not yet sent Hannah and Daniel to Grasmere, partly because it seemed a bit of an obvious step, and I wanted to explore one or two less familiar locations. But I do like Grasmere very much, and it may be time that it featured in one of my books. Meanwhile, I was very glad to sign books in Sam Read, the lovely local bookshop. What I think may be happening in quite a few cases, by the way, is that readers who sample my books (and those by others) as ebooks are starting to buy traditional print copies in the shops. Several people have told me that they've done this, and it does seem interesting that perhaps more of a crossover may develop between online and actual book retailing than has been thought likely in the past. Another terrific bookshop, Fred Holdsworth's of Ambleside (above), featured on my itinerary on my way home. Again, it's good to see a proud independent bookshop really thriving, and playing an important part in the local community, and I was delighted to catch up over a coffee with Steve, the owner. And as I toured the area, with research for the next novel in mind, I took in Stagshaw Gardens, Holehird Gardens, Kendal, and Sedbergh. It's a lovely part of the world, and now of course the Lake District is becoming a UNESCO World Hetitage site. About time too!

Another terrific bookshop, Fred Holdsworth's of Ambleside (above), featured on my itinerary on my way home. Again, it's good to see a proud independent bookshop really thriving, and playing an important part in the local community, and I was delighted to catch up over a coffee with Steve, the owner. And as I toured the area, with research for the next novel in mind, I took in Stagshaw Gardens, Holehird Gardens, Kendal, and Sedbergh. It's a lovely part of the world, and now of course the Lake District is becoming a UNESCO World Hetitage site. About time too!

Published on July 20, 2017 02:30

July 17, 2017

Catriona McPherson - guest blog

Catriona McPherson is a highly successful Scottish author who has become very popular in both sides of the Atlantic. I've enjoyed meeting her at several conventions, and to celebrate the publication of her latest novel, Dandy Gilver & a Spot of Toil and Trouble, I'm delighted to welcome her to this blog with this guest post.

"For the first ten years of my writing career I lived in Scotland, producing books set in Scotland (and one in Leeds) that were published in London. It was so easy. Then, in 2010, I moved to California, added a New York publisher and everything got much more complicado.

For a start, research has to be squashed into a month or so every summer when I’m back in the old country. And that month might be after I’ve turned in the book. Also, I haven’t experienced a British winter for seven years now and need to keep a post-it note on my monitor saying “It’s probably raining!” just to remind me. I can feel sympathy draining away, though, so I’ll move on to the big issue.

The big issue, of course, is the deep chasm in our common language.

One US editor now produces three lists of problem words:

Cultural references. We can usually kill these in the contemporary novels because no book lives or dies on mentions of Ribena, Barnardos or Heartbeat, now does it? In the 1930s, it’s a bit tougher. Pantomines, Punch and Judy shows, the Regional Programme . . . there’s a lot of historical texture in those social details.

Standard differences. These have to be managed with some finesse because fictional British people cannot speak American English. British characters just can’t say “pea coat” when they mean “donkey jacket”, or “stucco” when they mean “harling”. (The answer is usually that the character wears a duffel coat and the house is whitewashed.) Pudding is always a problem, though. Dandy Gilver can’t say “dessert” (My dear!) And clothes are a blimmin’ nightmare. Jumpers and vests, knickers and pants. A novel set in a naturist colony would be a great relief. I do get a bit shirty (no pun intended)Then there’s the non-standard dialect breenging in, all bolshy, turning the editor crabbit enough to start a stooshie. Here the London editor sometimes gangs up on me with the US editor. We slug it out in an unfair fight. I try to keep as many as I can, especially in the Dandy Gilver novels, because she’s English and can translate for the readers. The editor usually gives a lot of ground but insists on a wee-ectomy. That’s a fair point. It’s quite startling how often Scottish people use the word “wee”, and rarely to mean “small”. I got 86 uses down to 35 last time.

“Wee” aside, I’m interested to know whether readers mind a smattering of unintelligible dialect in books? Or do you even – this would be a great weapon for the next fight – relish it?

And if anyone knows what a credenza is, do tell me.".

Published on July 17, 2017 03:00

July 14, 2017

Forgotten Book- Death By Two Hands

My Forgotten Book for today is another by Peter Drax. Death By Two Hands was first published in 1937, and until Dean Street Press reprinted six Drax books, it was the only one I'd ever found in a first edition. Like Murder on the High Seas, it's unusual for a crime story of the 30s, because it centres exclusively on working class people, with not a country mansion or secret passage in sight.

A young woman called Alma Robinson leaves her home town to live with her disreputable uncle, and becomes a pawn in a criminal game. A dodgy dealer called Rivers hires the ruthless Spike Morgan to steal a consignment of fox furs. Spike and his sidekicks carry out the plan, but things go wrong, and a man is killed. Soon there is another death...

Drax describes the crime with a realism that we tend to associate more with post-war novels than those of the 30s. He's also pretty convincing when it comes to police procedure. Chance plays a part in the investigation, but the story unfolds in a believable way, and there's a small twist right at the end. The treatment of criminals and their activities is much more convincing than was often the case during the Golden Age.

I'd also like to mention the quality of Drax's writing. He has a very good turn of phrase, and his observations are perceptive and convincing. His evocation of character is excellent, and the book is also good on urban settings. Drax's world is very far removed from Mayhem Parva. I'm surprised these novels weren't better known in the 30s, and I'm delighted that Dean Street Press have reprintged them.

A young woman called Alma Robinson leaves her home town to live with her disreputable uncle, and becomes a pawn in a criminal game. A dodgy dealer called Rivers hires the ruthless Spike Morgan to steal a consignment of fox furs. Spike and his sidekicks carry out the plan, but things go wrong, and a man is killed. Soon there is another death...

Drax describes the crime with a realism that we tend to associate more with post-war novels than those of the 30s. He's also pretty convincing when it comes to police procedure. Chance plays a part in the investigation, but the story unfolds in a believable way, and there's a small twist right at the end. The treatment of criminals and their activities is much more convincing than was often the case during the Golden Age.

I'd also like to mention the quality of Drax's writing. He has a very good turn of phrase, and his observations are perceptive and convincing. His evocation of character is excellent, and the book is also good on urban settings. Drax's world is very far removed from Mayhem Parva. I'm surprised these novels weren't better known in the 30s, and I'm delighted that Dean Street Press have reprintged them.

Published on July 14, 2017 10:00

July 12, 2017

The House Across the Lake - 1954 film review

I didn't know what to expect when I settled down to watch a British crime film from 1954. But The House Across the Lake turned out to be set around Windermere, and featured a struggling crime writer as the conflicted protagonist. Needless to say, this premise grabbed my attention right away!

Alex Nicol plays Mark Kendrick, an American writer based in the UK (for unexplained reasons) who rents a place in the Lakes as he tries to meet a deadline for his latest book. He encounters a blonde femme fatale, also played by an American, Hillary Brooke. She happens to be married to a rich man - played (rather to my amazement) by Sid James, in a rare straight role. She's well-known for dallying with other men, and Kendrick befriends the husband but becomes besotted by the wife - rather surprisingly, since the husband's daughter from an earlier marriage, played by Susan Stephen, seems much more appealing.

Anyway, we are in classic film noir territory here. The storyline owes a great deal to Double Indemnity, although it's based on a book called High Wray by Ken Hughes, who directs the film (and later directed many others, including Chitty, Chitty, Bang Bang). Although it's not very original, it's well done, at least until the very rushed finale, which I found anti-climactic.

There's fun to be had in spotting the other cast members -including Joan Hickson, Paul Carpenter, John Sharp, and Alan Wheatley (later famed as the Sheriff of Nottingham in Robin Hood). I hoped the titular house would prove to be Wray Castle, which I enjoyed visiting a few years back, but it wasn't to be. However, I did enjoy this short film. Definitely worth watching. Why was it called Heat Wave when released in the US? Your guess is as good as mine.

Alex Nicol plays Mark Kendrick, an American writer based in the UK (for unexplained reasons) who rents a place in the Lakes as he tries to meet a deadline for his latest book. He encounters a blonde femme fatale, also played by an American, Hillary Brooke. She happens to be married to a rich man - played (rather to my amazement) by Sid James, in a rare straight role. She's well-known for dallying with other men, and Kendrick befriends the husband but becomes besotted by the wife - rather surprisingly, since the husband's daughter from an earlier marriage, played by Susan Stephen, seems much more appealing.

Anyway, we are in classic film noir territory here. The storyline owes a great deal to Double Indemnity, although it's based on a book called High Wray by Ken Hughes, who directs the film (and later directed many others, including Chitty, Chitty, Bang Bang). Although it's not very original, it's well done, at least until the very rushed finale, which I found anti-climactic.

There's fun to be had in spotting the other cast members -including Joan Hickson, Paul Carpenter, John Sharp, and Alan Wheatley (later famed as the Sheriff of Nottingham in Robin Hood). I hoped the titular house would prove to be Wray Castle, which I enjoyed visiting a few years back, but it wasn't to be. However, I did enjoy this short film. Definitely worth watching. Why was it called Heat Wave when released in the US? Your guess is as good as mine.

Published on July 12, 2017 13:13

The Azure Hand - guest post by Cally Phillips

As a result of my writing activities, I've received many fascinating "out of the blue" contacts from people from all parts of the world. These are often not only enjoyable but also informative. So it was when I was contacted by Cally Phillips last year. She told me about a book and author I'd never heard of. I was tempted to explore further, and I'm very glad I did. The book in question was The Azure Hand, which thanks to Cally's enterprise is now being republished. I've invited Cally to tell the story herself:

"The Azure Hand was first published on 24th July 1917, one of several posthumous works by the writer Samuel Rutherford Crockett, who died in April 1914. Crockett is better known, where he is known at all any more, as the writer of stirring ‘boys own’ stories of history, adventure, romance set in rural Scotland, France or Spain. Once dismissed as ‘Kailyard’ he has more recently been seen as coming from the Stevensonian tradition.

In his lifetime he lay claim to more than sixty published works of fiction and he is hard to pin down because over the twenty plus years of his writing career he adapted and adopted different styles in order to keep in step with the changing fashions of popular fiction. It was not always a successful tactic and the fact that The Azure Handwas never published in his life-time suggests it was one of his ‘failures’. However, with a centenary edition now due out, a new generation of readers are able to judge for themselves exactly what kind of book this is.

As a detective fiction novel it is unusual, though not unique among Crockett’s work. He started experimenting with this form – via ‘sensationalist’ fiction in the early 1900s, but he never seemed to quite ‘hit the mark’ for the market at the time. Looking back with the benefit of a century of hindsight however, we can see that he was in fact being quite experimental both in form and content and The Azure Handdating well before the Golden Age of Crime presages it in some ways. It is, to quote Martin Edwards a: ‘very modern take on fictional detection. It shows a determination to pick up some of the then popular tropes (clues, footprints etc) and do something relatively fresh with them.’

In 1917 Crockett’s widow, chasing an income from his royalties, persuaded Hodder and & Stoughton (with whom he had a long and fruitful connection) to publish The Azure Hand. Being during the First World War it was a small print run and the quality of the publication was poor – and it soon went out of print into obscurity.

Ayton Publishing Limited was set up in 2012 with the explicit aim of promoting works by and about Crockett. In 2014 the 32 Volume Galloway Collection was published to commemorate the centenary of his death. This was followed in 2015 by The Rainbow Crockett series (seven of his works for children) and since then sundry other works by and about him have been published and re-published. It seemed only fitting to bring out The Azure Hand on the centenary of its original publication date.

You can purchase the Ayton Publishing centenary edition in paperback direct from www.unco.scot online for the discounted price of £9.99.

To find out more about the life and work of S.R.Crockett you can visit the Galloway Raiders website www.gallowayraiders.co.uk which is the home of the S.R.Crockett literary society and a great place to start your exploration of all things Crockett related."

"The Azure Hand was first published on 24th July 1917, one of several posthumous works by the writer Samuel Rutherford Crockett, who died in April 1914. Crockett is better known, where he is known at all any more, as the writer of stirring ‘boys own’ stories of history, adventure, romance set in rural Scotland, France or Spain. Once dismissed as ‘Kailyard’ he has more recently been seen as coming from the Stevensonian tradition.

In his lifetime he lay claim to more than sixty published works of fiction and he is hard to pin down because over the twenty plus years of his writing career he adapted and adopted different styles in order to keep in step with the changing fashions of popular fiction. It was not always a successful tactic and the fact that The Azure Handwas never published in his life-time suggests it was one of his ‘failures’. However, with a centenary edition now due out, a new generation of readers are able to judge for themselves exactly what kind of book this is.

As a detective fiction novel it is unusual, though not unique among Crockett’s work. He started experimenting with this form – via ‘sensationalist’ fiction in the early 1900s, but he never seemed to quite ‘hit the mark’ for the market at the time. Looking back with the benefit of a century of hindsight however, we can see that he was in fact being quite experimental both in form and content and The Azure Handdating well before the Golden Age of Crime presages it in some ways. It is, to quote Martin Edwards a: ‘very modern take on fictional detection. It shows a determination to pick up some of the then popular tropes (clues, footprints etc) and do something relatively fresh with them.’

In 1917 Crockett’s widow, chasing an income from his royalties, persuaded Hodder and & Stoughton (with whom he had a long and fruitful connection) to publish The Azure Hand. Being during the First World War it was a small print run and the quality of the publication was poor – and it soon went out of print into obscurity.

Ayton Publishing Limited was set up in 2012 with the explicit aim of promoting works by and about Crockett. In 2014 the 32 Volume Galloway Collection was published to commemorate the centenary of his death. This was followed in 2015 by The Rainbow Crockett series (seven of his works for children) and since then sundry other works by and about him have been published and re-published. It seemed only fitting to bring out The Azure Hand on the centenary of its original publication date.

You can purchase the Ayton Publishing centenary edition in paperback direct from www.unco.scot online for the discounted price of £9.99.

To find out more about the life and work of S.R.Crockett you can visit the Galloway Raiders website www.gallowayraiders.co.uk which is the home of the S.R.Crockett literary society and a great place to start your exploration of all things Crockett related."

Published on July 12, 2017 07:39

July 10, 2017

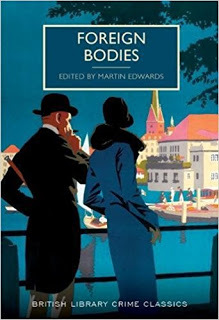

Foreign Bodies

I've been putting the finishing touches to a British Library anthology that I'm really excited about. This is Foreign Bodies, a collection of classic crime in translation that includes several real gems. I'll be saying more about this book in the coming weeks - it's due to be published in October - but certainly foreign crime fiction is very much in my mind just at the moment.

I've been putting the finishing touches to a British Library anthology that I'm really excited about. This is Foreign Bodies, a collection of classic crime in translation that includes several real gems. I'll be saying more about this book in the coming weeks - it's due to be published in October - but certainly foreign crime fiction is very much in my mind just at the moment.

I've been doing some research on the history of crime fiction in non-English speaking languages, and this has reintroduced me to some very interesting authors and stories. And also to one of the great characters of the genre. Eugene Francois Vidocq was not a crime novelist, but his Memoirs were a big success in Britain as well as in Europe, and he influenced plenty of major writers whose work touched on crime. Coincidentally, I visited his birthplace, Arras, in north eastern France while on a brief trip a couple of weeks ago. I really liked Arras, and as well as visiting the citadel, explored the belfry and the mysterious tunnels beneath the main square. A charming town, though I think they could make more of the Vidocq connection.

I've been doing some research on the history of crime fiction in non-English speaking languages, and this has reintroduced me to some very interesting authors and stories. And also to one of the great characters of the genre. Eugene Francois Vidocq was not a crime novelist, but his Memoirs were a big success in Britain as well as in Europe, and he influenced plenty of major writers whose work touched on crime. Coincidentally, I visited his birthplace, Arras, in north eastern France while on a brief trip a couple of weeks ago. I really liked Arras, and as well as visiting the citadel, explored the belfry and the mysterious tunnels beneath the main square. A charming town, though I think they could make more of the Vidocq connection.

The reason I got to Arras was that I'd figured out that a trip on Eurostar from St Pancras to Lille takes less time than a train ride from nearby Euston to my local stations, Warrington and Runcorn. So it was time to visit Lille, and I'm glad I did. Vauban's citadel is well worth a look, as is the (relatively modern) belfry and the rather unusual cathedral. Lille also boasts a Sherlock Holmes pub...

The reason I got to Arras was that I'd figured out that a trip on Eurostar from St Pancras to Lille takes less time than a train ride from nearby Euston to my local stations, Warrington and Runcorn. So it was time to visit Lille, and I'm glad I did. Vauban's citadel is well worth a look, as is the (relatively modern) belfry and the rather unusual cathedral. Lille also boasts a Sherlock Holmes pub...

In some ways, the highlight of the very short trip. was a visit across the border, to Tournai in Belgium. I loved the triangular main square, and the fascinating architecture all around. The cathedral is magnificent, although currently undergoing major renovations. And I also had time to read a couple of Golden Age books that will feature in Forgotten Books before too long.

Published on July 10, 2017 15:06

July 8, 2017

The Birthday after the Blog Tour

On Friday I celebrated another birthday with a trip to North Wales. There are those who argue that once you get to a certain age, you shouldn't fuss over birthdays, but I take the opposite view. It's good to have a chance to reflect on the past twelve months, and perhaps to look ahead, if not too far ahead. So following my custom, I enjoyed my day out, and along the way mused on a hugely enjoyable year.

On Friday I celebrated another birthday with a trip to North Wales. There are those who argue that once you get to a certain age, you shouldn't fuss over birthdays, but I take the opposite view. It's good to have a chance to reflect on the past twelve months, and perhaps to look ahead, if not too far ahead. So following my custom, I enjoyed my day out, and along the way mused on a hugely enjoyable year.

The icing on the birthday cake was the news that the British Library are already reprinting The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books, only a few days after publication. Very gratifying, as are the early reviews - so I felt I was entitled to a day off from writing! I'd been very busy penning guest posts for the British and American bloggers who were kind enough to host my blog tour, and I was ready for a break.

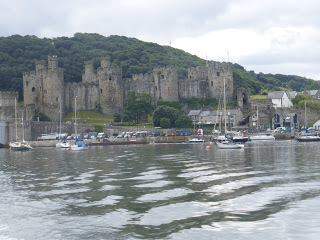

The icing on the birthday cake was the news that the British Library are already reprinting The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books, only a few days after publication. Very gratifying, as are the early reviews - so I felt I was entitled to a day off from writing! I'd been very busy penning guest posts for the British and American bloggers who were kind enough to host my blog tour, and I was ready for a break. I love boat trips, and for the first time in my life, I took a trip on the River Conway - both down river, and then out into the mouth of the river, where the views gave me a fresh perspective on a familiar and very lovely landscape. Conwy Castle, which I first visited as a small child, is of course the highlight, and the old town is full of interesting nooks and crannies. It's part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and rightly so.

I love boat trips, and for the first time in my life, I took a trip on the River Conway - both down river, and then out into the mouth of the river, where the views gave me a fresh perspective on a familiar and very lovely landscape. Conwy Castle, which I first visited as a small child, is of course the highlight, and the old town is full of interesting nooks and crannies. It's part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and rightly so.

Then it was off to Anglesey, and a tour round another old castle, also part of the World Heritage Site - Beaumaris. I've seen it from the outside plenty of times,, but I'd never ventured inside before, and was duly impressed. Next stop was the seaside, and Benllech Bay, before the return trip to Lymm, and an excellent meal out. Great fun. And the next day, I was back at work on the new book, honest!.

Then it was off to Anglesey, and a tour round another old castle, also part of the World Heritage Site - Beaumaris. I've seen it from the outside plenty of times,, but I'd never ventured inside before, and was duly impressed. Next stop was the seaside, and Benllech Bay, before the return trip to Lymm, and an excellent meal out. Great fun. And the next day, I was back at work on the new book, honest!.

.

.

Published on July 08, 2017 14:29

July 7, 2017

Forgotten Book - Neck and Neck

Leo Bruce's books are much admired by Golden Age enthusiasts such as Barry Pike, who also once put together a pleasing volume of his short stories, but they are no longer well-known in the UK. There were some reprints in the US some years back, but in his native country, Bruce has been neglected for far too long. I've previously praised his excellent debut, Case for Three Detectives, in particular. Today I'm turning my attention to the final Sergeant Beef novel, published in 1950, Neck and Neck.

It's difficult to say too much about this book without a major plot spoiler, but I'll try to skirt round the central device. As usual, the story is narrated by Lionel Townsend, but in this book there's a difference - he and his brother are potential suspects in connection with the murder of his wealthy aunt. A third potential suspect has, in fact, been disinherited, and in any event has an alibi for the time of the aunt's death. So it's all rather baffling. Is Lionel's brother really guilty? Or is there some unknown motive?

Beef is also working on a death in the Cotswolds. A rascally publisher has been murdered, and the author has some fun at the expense of unscrupulous vanity publishers. The storyline darts hither and thither, but without ever becoming unduly distracting. Beef is, as usual, a commanding figure, and Lionel seems rather more sympathetic than usual, even though we suspect he has something to hide.

It may be that there are no original whodunit plots, but certainly the central idea here is handled in a way that struck me as fresh and pleasing. Even though I knew roughly what was going on, I found the story readable and enjoyable. A good mystery that certainly deserves to be better known.

It's difficult to say too much about this book without a major plot spoiler, but I'll try to skirt round the central device. As usual, the story is narrated by Lionel Townsend, but in this book there's a difference - he and his brother are potential suspects in connection with the murder of his wealthy aunt. A third potential suspect has, in fact, been disinherited, and in any event has an alibi for the time of the aunt's death. So it's all rather baffling. Is Lionel's brother really guilty? Or is there some unknown motive?

Beef is also working on a death in the Cotswolds. A rascally publisher has been murdered, and the author has some fun at the expense of unscrupulous vanity publishers. The storyline darts hither and thither, but without ever becoming unduly distracting. Beef is, as usual, a commanding figure, and Lionel seems rather more sympathetic than usual, even though we suspect he has something to hide.

It may be that there are no original whodunit plots, but certainly the central idea here is handled in a way that struck me as fresh and pleasing. Even though I knew roughly what was going on, I found the story readable and enjoyable. A good mystery that certainly deserves to be better known.

Published on July 07, 2017 03:19

July 3, 2017

The Girl in a Swing - film review

Long before The Girl on the Train, there was The Girl in a Swing. This was a novel, the fourth by Richard Adams, famed as author of Watership Down. In 1988, it became a film which is the subject of this review - but in this movie, there's not a rabbit in sight. It's really a horror story with erotic elements, and a few supernatural touches.

Alan Desland (played by Rupert Frazer) is a posh young antiques dealer. Good-looking and well-mannered, he is attractive to women, but when a pretty girl throws herself at him, he's not interested. There's something repressed about him, but he begins to lose his inhibitions while on a trip to Copenhagen, when he falls head over with a young German secretary (Meg Tilly).

The girl is rather mysterious, but she falls for Alan, and agrees to marry him. However, she disappoints him by refusing to marry in church, and there are other odd aspects to her behaviour. After early mishaps, their sex life becomes increasingly adventurous, but a sequence of strange little incidents causes Alan understandable concern. What exactly is going on only becomes apparent late in the film, and the explanation pulls the various story strands together reasonably well.

It also makes it easier to understand why Alan's character is key to the storyline. I have to say I found him distinctly lacking in charisma, though the same cannot be said of his co-star, Meg Tilly. Nicholas Le Prevost, a dependable actor, plays the part of Alan's best friend, who happens to be a vicar, and there's a role for Jean Boht, whose husband Carl Davis wrote the soundtrack. Quite watchable, and although scarcely a classic comparable to Watership Down, I rather admire Adams for trying something so very different.

Alan Desland (played by Rupert Frazer) is a posh young antiques dealer. Good-looking and well-mannered, he is attractive to women, but when a pretty girl throws herself at him, he's not interested. There's something repressed about him, but he begins to lose his inhibitions while on a trip to Copenhagen, when he falls head over with a young German secretary (Meg Tilly).

The girl is rather mysterious, but she falls for Alan, and agrees to marry him. However, she disappoints him by refusing to marry in church, and there are other odd aspects to her behaviour. After early mishaps, their sex life becomes increasingly adventurous, but a sequence of strange little incidents causes Alan understandable concern. What exactly is going on only becomes apparent late in the film, and the explanation pulls the various story strands together reasonably well.

It also makes it easier to understand why Alan's character is key to the storyline. I have to say I found him distinctly lacking in charisma, though the same cannot be said of his co-star, Meg Tilly. Nicholas Le Prevost, a dependable actor, plays the part of Alan's best friend, who happens to be a vicar, and there's a role for Jean Boht, whose husband Carl Davis wrote the soundtrack. Quite watchable, and although scarcely a classic comparable to Watership Down, I rather admire Adams for trying something so very different.

Published on July 03, 2017 10:53