Gary Barwin's Blog: serif of nottingblog, page 11

October 29, 2021

How when we thought our daughter was going to be a "boy" is like my new novel.

our 3 kids and dog when our daughter was 3

our 3 kids and dog when our daughter was 3I was thinking about our daughter and my new book. We had a very, very early ultrasound and we thought our daughter was going to be a boy. Not that it mattered to us, but, having found out, we pictured this third child to be a certain kind of child, at least initially, as they’d come with standard features built in the factory as it were. To be honest, 25 years ago, we weren’t really thinking about gender vs. sex, though we were entirely open to how the presentation and definition of either might be seen and defined by our children. But, having imagined having three sons, having imagined this kid to be “a boy,” when our daughter was born, of course we were thrilled out of our minds, but my wife, since she was expecting this “boy” and had imagined what it might be like, in addition to feeling the delight of our girl, had to, if not mourn, then acknowledge the loss of that other kid she had anticipated (or more, correctly, our perceptions of that kid's starting point—we knew our kids would discover and develop into the people that they truly were as they grew.) It was just the loss of what she had anticipated, all that love flowing toward the image of that kid in her mind. There was, of course, the same immense love flowing toward our actual kid, the one who had actually been pictured in that ultrasound, the one who was actually born. And that love continues to this day for our remarkable third child (of course, the other two are no slouches either!)

But this is about me! About my recent novel. It occurred to me as I drifted off to sleep—ok, as I listened to the Tale of Genji on headphones mounted in a sleep mask (who can get to sleep any other way)—that this “loss” of our imaginary child was a bit like the loss of what I’d hoped for my novel, Nothing the Same, Everything Haunted: The Ballad of Motl the Cowboy which was published in Spring 2021. During a pandemic. It’s done fine. I was delighted by several really great reviews and by winning the Canadian Jewish Literary Award for Fiction for it. I’ve done a bunch of readings, mostly online, at festivals across the country. So no complaints. Well, one can always complain—and I can. But I guess, because this book was so important to me, because it speaks of the Holocaust, and my family’s history in Lithuania as well as Indigenous genocide, and because I worked so hard on it (of course who doesn’t work so hard on a novel?) I’d hoped it would make a bigger splash. Admittedly, my view was distorted by the marvellous and entirely surprising success of my previous novel, Yiddish for Pirates. It is still selling better than this new novel. Curses, other Gary who sells better than me! Only a fool would be jealous of himself and his previous book. Look into the mirror, Gary: fool.

I did hope that this book might have another path, but it has the path that it does. Maybe it’ll be a slow burn and readers will discover it more gradually. Maybe it’ll have fewer readers but it’ll mean more to them. Maybe when the paperback edition comes out in March, its red boot bedecked bright yellow cover will leap into readers hands. And now that bookstores are open again (ah, how I missed them!) that’s another chance for the book to meet its potential readers. Also, it’s being translated into Romanian! I may not be big in Japan, but Romania? They’ll carry me through the streets of Bucharest!

There’s that Junot Diaz quote, “In order to write the book you want to write, in the end you have to become the person you need to become to write that book.” And in some sense, you have to become the person you need to have written that book, to have that particular book out in the world. And you get to be another person, too. The one who is writing the current work-in-progress. I find I have to become that person in order to do that work, and I’m discovering who that person is through the process of writing.

So, there’s no point in mourning the book that could have been. The reception that could have been. The person that one could have been, that was. I hadn’t thought of that chimerical “son” that we thought we might have. In fact, by not having any expectations of our daughter—who she might be and how—we’ve been delighted by the continual discovery. Now that’s the way to have joy as a parent and as a writer.

October 21, 2021

Some words on Michael Chabon

This past Tuesday, I had the great pleasure of interviewing American novelist, Michael Chabon for an event at the Jewish Public Library in Montreal. I thought I'd share my introduction since I got to wax a bit poetic.

It was kinda funny in that, at least in our current incarnations, Chabon and me looked a little alike -- long grey hair, big black-rimmed glasses and beards. I joked that I was cosplaying him, ready to attend a Chabon-con.

*

I’m so very delighted to have the opportunity to have Michael Chabon join us tonight to speak about his remarkable and wide-ranging body of work.

So, what have I learned from his writing?

That language is a golem, a superhero, a doula, the moon. Language is a kid dressed with astounding style and agency, a kind of fatherhood of the world. And motherhood. Language is a map, a legend, a rocket, a secret plan, a beloved city, an entire cosmos, a marvellous escape and a transformation.

For Chabon, language is also a song, a memory, and an instrument of curiosity, and investigation.

It’s a magic trick of surprise, invention, wonder and empathy. And perhaps especially empathy. In Michael Chabon’s many novels and essays we come to know the world, and we come to know how the people in that world understand that world. Or try to.

More than it being a brave new world, I feel that his work explores the brave people in that world finding their way, with all their contradictions, regrets, reinventions and attempts to reclaim, rebuild or maintain their selves.

He writes in The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay that, “We have the idea that our hearts, once broken, scar over with an indestructible tissue that prevents their ever breaking again in quite the same place...”

Ben Marcus has remarked on Chabon’s deep love for his subjects, how “he’d do anything to make his material come to life, he would die for it.” Marcus says. “Loyality, devotion and obsession… a deep instinctual passion” – we observe all of this in how Chabon writes. “He doesn’t want to let his material down.”

I should also note, since we’re here at the Jewish Public Library, that Chabon’s work is infused with a deep engagement with Jewishness and what that might mean for our idea of the past, the present and the future. He asks profound questions about what it means to be in the world, to engage with culture—not only Jewishness, but the culture of both history and the contemporary moment. What is it to be a father, son, partner, brother? Maybe what is it to be a mensch or to have inherited or developed ideas about one’s role in the world. How are we defined by and define ourselves by our passions and curiosity. By our creativity and relationships. And his work is both poetic, dramatic, moving, and funny.

But before we begin our discussion, first a few, an impossibly few, words about Michael Chabon’s staggering list of publications and awards.

His first novel, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh was published when he was 25. That makes me think of that Farley Mowat line, “If someone tells you writing is easy, they are either lying or I hate them.” This first novel and his next novel, The Wonder Boys were bestsellers and The Wonder Boys was made into a major motion picture.

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Klay won stacks of awards including the 2001 Pulitzer Prize and was included as one of 125 books most important books of the last 125 years by the New York Public Library. This very beloved book is being adapted by Chabon and his wife, the writer Ayelet Waldman into a TV series for Showtime. I can’t wait for that.

The Yiddish Policemen’s Union, the delightfully meshuggeh and dramatic counterfactual detective novel, made the jury of both the Nebula and Hugo award plotz with astonishment & so was awarded both those prizes.

Other novels include Gentlemen of the Road, Telegraph Avenue, and Moonglow. Chabon has also published graphic novels, YA work, short story collections and bestselling essay collections including Manhood for Amateurs, and, most recently, Pops. I hope we’ll have a chance to talk about all of these.

Chabon’s writing has won many awards including, The National Book Critics Circle, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, Pen/Faulkner, and National Jewish Book Award among many others.

It’s a remarkable thing that a writer of Chabon’s stature has also been involved in film and TV. He

produced, wrote and was the showrunner for the first season of the Star Trek series, Picard starring, of course, Patrick Stewart, and he has writing credits on the Spiderman 2 and John Carter movies. And as I mentioned, he’s working on a TV adaptation of Kavalier and Klay.

There’s lots more, of course, but rather than me going on, let’s speak to the man himself. Pleasures, regrets, maps, legends, amazing adventures, rockets, records, death by Hammond B3 organs. There’s so much to talk about. Please welcome Michael Chabon.

October 17, 2021

Canadian Jewish Literary Award and new paperback cover for NOTHING THE SAME, EVERYTHING HAUNTED

I was very delighted today to receive the Canadian Jewish Literary Award (Fiction) for the second time. I was for my second novel, Nothing the Same, Everything Haunted: the Ballad of Motl the Cowboy. The ceremony was very moving and inspiring. The other winners were so thoughtful, interesting, inspiring and articulate. Here's their website with all the winner.

I gave a short speech which I thought I'd post here, below. I'm also sharing the draft of the cover of the paperback version of the book (above) which will be out soon. It's beautiful, another brilliint cover by the designer Andrew Stevens. I'm calling this cover a reboot. And that yellow is custard's last stand.

The Speech

It very moving to receive a Jewish award for a novel about the Holocaust, particularly one that draws deeply on the story and experiences of my family and their history in Lithuania.

Literature can offer connection, empathy, understanding and consolation between those of vastly different experiences. It explains ourselves to ourselves but also to others.

And my book makes connections between the Shoah and Indigenous genocide. Once, the remarkable Metis writer, Cherie Dimaline said to me that “we’re genocide buddies.” Jews and Indigenous peoples. That’s brutally true. And important.

Since I first encountered them as a teenager, I often think of these lines from Marvin Bell’s poem “Gemwood.” “Now it seems to me the heart /must enlarge to hold the losses /we have ahead of us.”

To me this means that while we must be ready for what the future brings, we must be also be ready for the extent of the losses of the past and present as we continue to learn. Like the universe itself, both past and present never stop expanding. That’s one function of writing. To expand but also to encounter that expansion, those stories.

So there’s an old joke about when Abe finally meets God and tells him a Holocaust joke. God doesn’t get it. Well, says, Abe, guess you had to be there.

Without parsing the theological implication of that joke, I can say that it the role of writers particularly to “be there” – to act as witnesses, as witnesses to the witnesses, and to allow others to “be there,” both now and in the future. And also to be vigilant about that present and that future. So that no one can say they didn’t know, or didn’t notice. About any genocide or persecution.

My novel weaves broad research with stories I learned directly from my family, including my grandparents, my parents, my in-laws, our family friend, Erwin Koranyi, and my great-uncle Isaak Grazutis, a painter, who as a child, literally walked himself to safety. I am, course, deeply grateful to all of them and to the survivors and researchers for sharing their stories and knowledge.

I’d like to thank my agent, Shaun Bradley and my editor, Anne Collins and my parents, in-laws, siblings, children and my wife, Beth for their continued support, enthusiasm and curiosity.

And thank you to the jury and to supporters of the Canadian Jewish Literary Awards. As I said this really mean a lot to me.

I’d like to end with a story about the great Yiddish poet and resistance fighter, Avram Sutzkever which I paraphrase in my novel. He had found himself having to cross a minefield and, having no idea where the mines were, didn’t know where to step. He decided, because it was as good an idea as any, to put his faith in literature and walk across the minefield in the rhythm of a poem. Miracle of miracles, he made it safely across the field. In an interview he gave years later he said, “Ach, I wish I could remember what the poem was, because it turned out to be a very useful poem.” So there’s that. Putting one’s faith in the power of literature to give hope, to guide, to surprise and outwit, and to take you through dangerous places. provide a good story, a good punchline, and sometimes, a happy ending.

Thank you.

September 28, 2021

VIDEOS, ROCKS, TEETH, SCISSORS, RAIN. A FEW RECENT VIDEOS.

I thought I'd share some recent videos that I made. Two with the US/Kerala poet and artist Dona Mayoora. We have a new book out together from Gap Riot Press. It's here at this link.

The second two videos are explorations using stopmotion. One with teeth and rocks, the second with Letraset

RAIN (with Dona Mayoora)

THE FORGIVENESS OF SCISSORS (with Dona Mayoora)

July 7, 2021

Flying is just falling with good PR: An essay on writing

All year as writer in residence, I was thinking about writing and I came up with some theories and so I wrote an essay/prose poem about it. rob mclennan has published in on his periodicity journal. It's here.

I woke up this morning wondering how is a lightbulb like a bird? It was dark, the sun was just beginning to rise, I could hear birds outside my window, chirping, squawking, singing.

June 16, 2021

Washing the Dishes: Ars Poetica

Sometimes when I wash the dishes, I am seized by the notion that I can attain some kind of transcendent absolute, will have brushed my scrubby against a joyful, radiant beauty if I can just clean every speck, every burnt skirmish from the surface of the pots and pans. It’s a lovely idea really, but perhaps I’d be better off cleaning the dishes reasonably well, learning to appreciate the imperfections and burned-on rice fragments, and then leaving the kitchen and playing saxophone or organizing poetry readings which have a stubby, spattered, ill-attended beauty all of their own. Poetry is great at asking questions, at destabilizing and making us look things (language, life, baboons, dishes, abstractions) in a different or renewed way, asking where is the poem coming from –who and why are behind or in the poem—and what is the occasion that it was made for or presented. And how do we read things, including ourselves? What is stuff: language, the world, ideas, values, communication, looking, reading, hearing, speaking, listening, witnessing, making, power, bodies, hierarchies, values, life, poetry, thinking. And how are things connected to other things. What’s going on and what isn’t. Creative rioting, writhing, riting. Rising.

June 6, 2021

divoice, davace, dorwoose, device: autocorrect!

You know that maddening thing when you’re trying to write on computer, a phone or another device, and autocorrect changes what you’re saying? And you have to retype up to three times just to get the divoice, davace, dorwoose, device to type what you want? I’ve been thinking about that digital stutter, that push against language that seems to do something that it wants rather than what you want to do, and wondering how it might change our idea of language. Our sense of a template operating in the background. Or people behind the code. Behind the device. And how we have to dialogue with it, how we have to sculpt our use and presence in language, in communication. Or is this just a modern iteration of something we’ve always felt, perhaps just realized in real time with a technology?

June 1, 2021

Grammatical Memory: Finding my vestigial Irish English

where I grew up

where I grew up

I was listening to David Naimon interview Doireann Ní Ghríofa on his podcast “Between the Covers” (which I’d highly recommend) and just understood something I’d never understood before (in addition to all the things I learned from their discussion.) Doireann Ní Ghríofa has a captivating voice, rich with the sound of an Irish speaker of English. (She speaks and writes in Irish, also. And her reading voice is particularly mesmerizing.)

I grew up in Co. Antrim, Northern Ireland and left when I was 9 for Canada. We weren’t Irish—my Litvak parents moved there from South Africa—but obviously Ireland was formative in my acquisition of the English language. I know that there are things I continue to stumble over, all these years later, hesitating between a North American locution and a Northern Irish one. I don’t have an Irish accent, though I do retain something of my earlier language context. For example, I say “carn’t” instead of the more normative North American “can’t.” And I sometimes feel a grammatic difference, an unfamiliarity, an undertow, when I speak though I am monolingual and haven’t lived in Ireland for 48 years. I also feel this pull when I listen to Irish people speaking English. Sure, I have an identification, a kind of nostalgia for my childhood. I do adore Ireland and the sounds of Hiberno-English as it is called, from both North and South in all its varieties. But I think there is something more happening. I know I feel a related kind of pull from the kind of English Jews speak, particularly Yiddish inflected speech. That’s an identification more than actual exposure, I think. Sure, there was some of that kind of speech in my parents’ and my grandparents’ speech patterns but not very much, at least not that I remember. And certainly, I didn’t speak this way. For me, I began to channel it more during and after when I was writing my novel, Yiddish for Pirates.

But back to Ireland. In the way that I’m pulled by the colours, textures, smells, tastes, stories and landscapes of my Irish childhood—and, I must admit, the ways in which I have recreated them in my own mind over the years, I also have that sense of language as a landscape. I’m not nostalgic for it, and though I certainly feel somewhat of an identification, a leaning in, an impulse to ventriloquize greater Irishness when I hear it, there’s an earlier layer of language acquisition at work I think. (When I last returned to Ireland, to Dublin, I showed my Canadian passport and the custom officer said, “Welcome home,” because she saw that I was born in Belfast. I didn’t say, “Ah to be sure,” but somewhere in my brain, it was forming in all its fake liltedness—not that I ever had that kind of accent—I was from the North.)

But this is what I think I learned listening to the podcast. My connection to this speech isn’t just the leaning in of identification, of wanting to participate in a group, but it the fossilized traces of my earlier understanding of language. A kind of lingual body memory. I feel like I'm always in translation.

And to think I thought I was a poser—or only a poser. I wouldn’t say it now, but I think “he’s only codding around.” “What a desperate wee maun.” “Och aye.” It’s harder to explain the grammatical pull, the shape, the pacing, the contours of language rather than just phrases. My voice was very high, more than was usual for a North American man, and it had the uptalk of Northern Ireland. In my early 20s, I began to deliberately lower its register and to lose the uptalk to meet more normative notions of the male voice and thus, I suppose, masculinity.

What other vestigial grammars exist in my speech? What viral inflections? I mean other than the voice of my Grade 7 teacher speaking about spelling and grammar. Language and speech is sedimentary, not only over historical time, but within each voice.And so the texture, the flavour of how I experience the world, the conceptual and musical portals through which I experience life are suffused with this earlier sense of language. To paraphrase a Doireann Ní Ghríofa book title, ghosts haunt the throat.

Ethical Squonking: On the Coltrane-Rollins Continuum

1.

Right now I’m listening to Sonny Rollins play, “I’m An Old Cowhand,” off his 1957 album, Way Out West. I put it on because earlier today I tweeted, “I feel like I'm Sonny Rollins when I want to speak to the world like Coltrane. Really, what an astounding thing if one could be Rollins.”

Of course, you remember that old story about how Rollins heard Coltrane and so stopped performing, instead going out to the Williamsburg Bridge to practice, questioning his vocation as a musician. “Sure,” Rollins is said to have thought, “he was good, but Coltrane was important.” What to do in the face of such possibility, such importance? Was it enough to just be a marvellous and virtuoso player or should one strive for the wisdom, depth and transcendent spiritual and political significance of Coltrane. Or at least that’s how I remember the anecdote.

And in the face of the world, as I was learning saxophone, deciding what I wanted to do as a musician, composer and writer, I felt that I naturally should aspire to be on the Coltrane side of the Rollins-Coltrane divide. Gravitas. Wisdom. The spiritual, at least in the sense of digging deeply into the spirit of the world, of searching for insight beyond entertainment. As if it were the difference between being Bozo the Clown and Martin Buber. Chuck E. Cheese and Spinoza. (Though those pair-ups might make good MMA matches. I mean with enough grease.)

I should say that Rollins personally has been involved in spiritual pursuits and learning, particularly from Eastern traditions since the 60s and speaks of living a deeply spiritually informed life. I’m here talking about the Rollins-music avatar of my imagination and perception as I was earning my Vandoren's and Rico Royal 2 1/2s.

I once heard Sonny Rollins play in Toronto. It was a perfect summer day in the 80s when I was studying music at York University, and a bunch of us went to the Molson Amphitheatre on Toronto’s waterfront. We lay on the grass just outside the cover of the roof watching Sonny, the blue of Lake Ontario in our vision. I remember one extended solo by Rollins, where the band dropped out and it was just him. Such a delightful squonking. Low register honks. Motifs broken up and tossed around. Time made into a salad. And all of it connected with Rollins’ characteristically playful intelligence. As Wallace Stevens says, “the poem of the mind in the act of finding/ What will suffice."

Ok, so gravitas didn’t seem to be explicitly there and the Coltrane-like bursting the seams, burning through the gates to another world. But there was meaning. Significance. And humility. And the sense of deeply being oneself. How? For Rollins his playing is often all about “the mind in the act of finding.” And what will suffice? Intelligence. Resilience. Creativity. Joy. A celebration of being. Of communication.

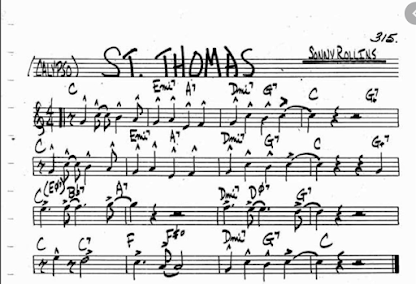

And the other thing I’ve come to understand in Rollins’ approach is ethics. Living through action and making choices. In a recent interview, Rollins says, “I’m just progressing through life, able to evolve now and to realize that to really live in a spiritual way I have to be an ethical person.” In his music I hear this decision to live ethically. To be in the world. To choose one note after the other as an ethical act. To embrace life. To choose positivity, communication, joy. The life-force. To keep playing, performing. To be an old man and to St-Thomas-the-hell out of life.

It's an astounding thing.

2.

So, all that’s true. I admire Rollins. He’s a giant of jazz and the saxophone and seems a profoundly great guy. And now, at almost ninety, he’s unable to play anymore, but is giving thoughtful and inspiring interviews and has a lengthy career to look back on. A “Saxophone Colossus” indeed. As I’ve gotten older, I have learned to consider practice, to consider action in the world as an ethical act. Unlike when I was younger, I wouldn’t only wander around, or loll about considering things, perhaps leaving a poetic trail like some Basho traipsing through the deep north that is Canada. Being there. For myself and for others. For my family, for example.

However, I couldn’t forget that thing that I heard in Coltrane. That sense of numinosity but also of penetrating humanity. That thing that I heard in the chanting of Hebrew prayer in my boyhood synagogue. That was the Trane that I was chasin’ in tracks like “Alabama” and “A Love Supreme” and “My Favorite Things.” I’ve thought of it as “The Saxophonists’ Book of the Dead.” A guide to the most profound aspects of life. Or perhaps, it’d be more accurate to say, a map detailing the terrain, what was possible, what were the things to consider. So, I didn’t explore Coltrane’s infinity or his interstellar space. And I didn’t explore the infinity of Jewish theology, but rather gained an intimation of what my own world and identity might contain. What might be contained inside the blue velvet bandshell of my own mind.