Rob Wolf's Blog, page 3

August 12, 2021

Jackson Ford is Full of Sh*t (in a Good Way)

Jackson Ford has some things in common with his protagonist, Teagan Frost. Both use nom de plumes. And both can move sh*t.

With her telekinetic powers, Teagan can move inorganic objects while Ford (aka Rob Boffard) uses his creative powers to move plots at a rapid clip.

Ford, and his publisher, Orbit, have also moved the cultural needle—specifically, by bringing three books with sh*t (asterisk and all) into the world. The most recent contribution, The Eye of the Sh*t Storm, is the third in Ford’s The Frost Files series and continues Teagan’s attempts to learn about her origins while managing her government handlers and keeping Los Angeles safe from those with strange psychic powers like hers.

“Teagan is not a typical superhero because she resents her ability to move things with her mind,” Ford tells me on the new episode of New Books in Science Fiction. “She would much rather learn how to cook, be a professional chef, and own her own restaurant… Her ability has forced her into a life she has no desire to be a part of.”

In the interview, Ford discusses (among other things) profanity, pseudonyms, and why Teagan, despite her extraordinary power, still needs the help of regular people.

Born in South Africa, Ford splits his time between London and Vancouver. Under his real name, Rob Boffard, he is the author of the Outer Earth series and Adrift.

This is honestly one of the best interviews I’ve ever done. Nothing to do with me; Rob asked some genuinely insightful questions and made me look at my own work in new ways. Any Frost Files needs to hear this. https://t.co/EbtxoDCfEv

— Jackson Ford (@realjacksonford) August 13, 2021

July 22, 2021

Gautam Bhatia Explores Rebellion for Rebellion’s Sake in The Wall

Gautam Bhatia’s debut novel The Wall (Harper Collins, 2020) is set in Sumer, a city enclosed in an impenetrable, unscalable barrier that seems sky high. To its inhabitants, whose ancestors have lived there for 2,000 years, the place is more than a city or even a country—it’s their universe.

Sumer’s residents know something is on the other side but have no desire to explore beyond the wall. They are content with what they have, living comfortably with the resources, rules and hierarchies that have sustained them for centuries.

But every couple generations, some people crave more. In this generation, a group calling themselves the Young Tarafians are determined to breach the wall once and for all.

“It’s not that there is some kind of very visible and wretched oppression that’s keeping people down,” Bhatia tells me in the new episode of New Books in Science Fiction. “At the end of the day, the resources are distributed in a way that everyone has enough for at least a decent standard of life. So it’s not meant to be a dystopia, and that’s part of the point. … Rebellion need not only come from a situation of desperation … but you still may want to rebel and alter things.”

When the troika of powers that rule Sumer—the civil government, the scientists and the religious elite—prosecute the Young Tarafians’ eloquent leader, a young queer woman named Mithila, each side has an opportunity to make their case.

“It’s actually taking a great risk by going beyond the wall. And for what? That makes the conflict between those who want to go beyond the wall and those who want to stay a much harder conflict to resolve,” says Bhatia, who is a lawyer and constitutional scholar. “Both sides have good arguments. It shouldn’t be a very clear binary between who’s right or wrong.”

July 1, 2021

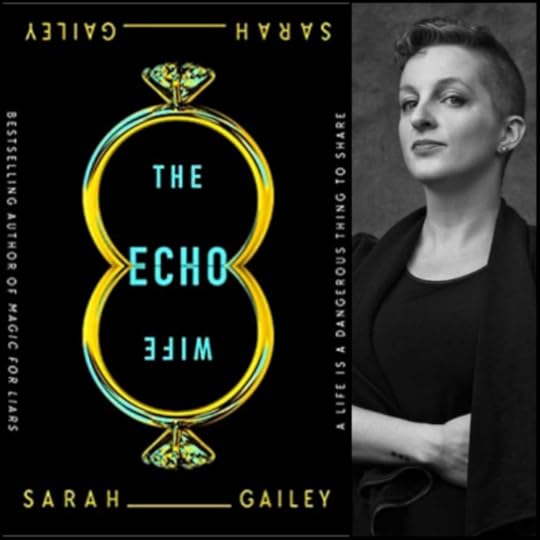

Cloning is a Cakewalk for the Geneticist at the Heart of Sarah Gailey’s The Echo Wife—Until She Meets Her Own Unwanted Double

https://traffic.megaphone.fm/NBN5584019256.mp3

Where does DNA end and the soul begin?

It’s a question that Evelyn Caldwell, the brilliant genetic researcher at the center of Sarah Gailey’s The Echo Wife, never asks as she develops her award-winning technique for human cloning, which takes DNA from “sample to sentience” in 100 days.

In The Echo Wife, clones are tools, created for specific time-limited purposes—to serve as a body double to draw fire from potential assassins, for example, or to provide donor organs. The question of a soul never enters into it. “Clones aren’t people. …They’re specimens,” Evelyn explains. “They’re temporary, and when they stop being useful, they become biomedical waste. They are disposable.”

Evelyn’s attitudes evolve when her ex-husband, Nathan, secretly uses the Caldwell Method to create Martine—a new wife scaffolded from Evelyn’s DNA but modified to be more docile and easy going. Because of Martine’s compliant nature (and complete reliance on Nathan for her knowledge of the world), Martine is eager to provide Nathan with the child Evelyn never wanted.

Evelyn is horrified by Martine’s existence—not only because Nathan stole her DNA to build a twin who lacks what Nathan calls Evelyn’s “needless venom,” but because Martine’s pregnancy should be impossible (clones are usually sterile) and threatens the future of the Caldwell Method.

Clones’ “inability to produce children is something that Evelyn uses to help maintain a sense of them being inhuman,” Gailey says. “So Martine’s pregnancy … poses a huge threat to all of Evelyn’s work.”

The pregnancy also poses a threat to Evelyn’s sense of self as she and Martine join forces to deal with multiple crises—murder and betrayal foremost among them—in addition to the pregnancy and Evelyn’s unexamined childhood traumas that contributed to her becoming a brilliant and fierce maverick.

Gailey’s debut novella, River of Teeth, was a Hugo and Nebula award finalist. In 2018, they won the Hugo Award for Best Fan Writer. They are the author of seven novels.

June 9, 2021

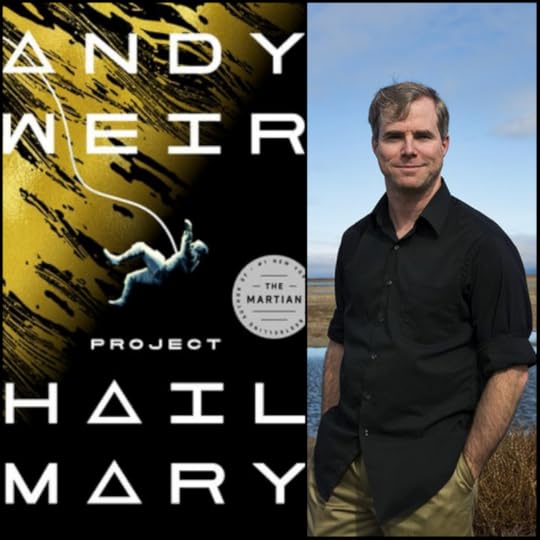

In Andy Weir’s Project Hail Mary, a reluctant astronaut is mankind’s best hope against a microscopic enemy

A story about an alien invasion typically revolves around diplomacy, military strategy, technological one-upmanship, and brinksmanship. But the invaders in Andy Weir’s Project Hail Mary are anything but typical.

Rather than a scheming sentient enemy, Weir gives us Astrophage, an opponent who is mindless—and microscopic. Similar to mold, Astrophage lives on—and taps energy from—the surface of stars.

“It’s not intelligent in any way. It doesn’t care about us. But it gets to the point where there is so much of it on our sun that the sun is starting to lose luminance—it’s getting dimmer. And a four or five percent dimming of the sun would be fatal to life on Earth,” says Weir, who was a guest on New Books in Science Fiction in 2014 to talk about his runaway bestseller The Martian.

An unlikely antagonist deserves an unlikely hero. Enter Ryland Grace, a middle school science teacher, who long ago authored a scientific paper that declared water isn’t a prerequisite for life. This once-ridiculed thesis draws the attention of the woman mustering the worldwide response to Astrophage. Eventually, Ryland finds himself waking from a years-long coma without remembering how or why he got there 12 light years from Earth, where he must figure out how to cure our sun of its infection.

While Astrophage is a deadly invader, another extraterrestrial plays a collaborative role. Thanks to the friendship that emerges between Ryland and Rocky, a hard-shelled, spider-like sentient creature with blood of mercury who breathes ammonia and hails from a planet with 29 times the atmospheric pressure of Earth, Project Hail Mary is as much a story about cross-cultural and cross-species exchange as it is a story of science, problem-solving and heroism.

May 19, 2021

The Twists and Turns of Evolution in Adrian Tchaikovsky’s The Doors of Eden

https://traffic.megaphone.fm/NBN1876923059.mp3

In Adrian Tchaikovsky’s The Doors of Eden, the multiverse is filled with parallel Earths where evolution takes different twists and turns.

The forks in the road and the paths species take vary from Earth to Earth, seeding sentience in a wide variety of organisms. In one, giant mollusks “understand and communicate profound truths about the nature of existence.” In another, a creature twice the size of the average human with traits of fish, salamander, and slug creates a permanent ice age and must upload its citizens to supercomputers to survive. Toddler-sized rats pave the planet with Industrial Age warrens in a different Earth. And in still another version of our planet, giant immortal spacefaring trilobites establish themselves at the top of the evolutionary heap for all eternity.

Read excerpts from my conversation with Adrian Tchaikovsky on Literary Hub.

Tchaikovsky’s characters learn about the existence of other Earths because the boundaries between them have sundered, necessitating urgent action. The challenge is no single species has the smarts or technology to fix the problem by itself. Thus they need to create an all-star team of the best and brightest among rats, trilobites, humans, and more if any their worlds hopes to continue.

While mankind’s dominance of Earth has often been mythologized as inevitable, The Doors of Eden presents a countervailing narrative, one that elevates chance as the most important factor in our species’ success.

“One of the big things you run into in studies of evolution is this assumption that we are what it was all aimed towards when, of course, we’re only one rung of the ladder that’s going to run a long way beyond us,” Tchaikovsky says. “If the conditions had been slightly different, we would have been very different. … How other sentient races might have developed from a completely different starting point was very much the point of the book, to be honest. I needed to find a plot that humans could get involved in that would showcase all of those different earths.”

April 28, 2021

A Lab-born Soldier Yearns for a New Life in Ginger Smith’s The Rush’s Edge

Space operas take readers far from Earth with stories about alien cultures and battles between good and evil. But while usually set in distant galaxies in the far flung future or past, they inevitably tell us, like any good science fiction, about our lives today.

Ginger Smith’s debut The Rush’s Edge takes place when humanity is spread across the galaxy and soldiers are born in labs, but it touches on subjects we grapple with now: blind loyalty to authority, the ethics of genetic science, and the prejudices that divide humans.

Halvor Cullen is a VAT—a member of the genetically engineered Vanguard Assault Troops who are programmed to be loyal to their commander and addicted to the rush of battle. VATs are released from duty after seven years of service, but their bodies burn out quickly, and they die young. But it’s when they’re released from duty that things get interesting. How does a person programmed to be a soldier find purpose or meaningful relationships when they’re no longer a soldier?

“VATs don’t get the chance to have a family or friends or the kinds of experiences we all take for granted,” Smith says. “Hal is learning a lot about what it means to be a human during this story. He knows about fighting but he doesn’t understand love, he doesn’t understand the difference between blind loyalty and the loyalty that people earn.”

Smith wrote The Rush’s Edge in a response to a challenge from her husband. “I’d played around in fanfic, and my husband said, ‘you’ve got to write something original.’ I said, ‘Fine, I’ll write you a book.’”

April 8, 2021

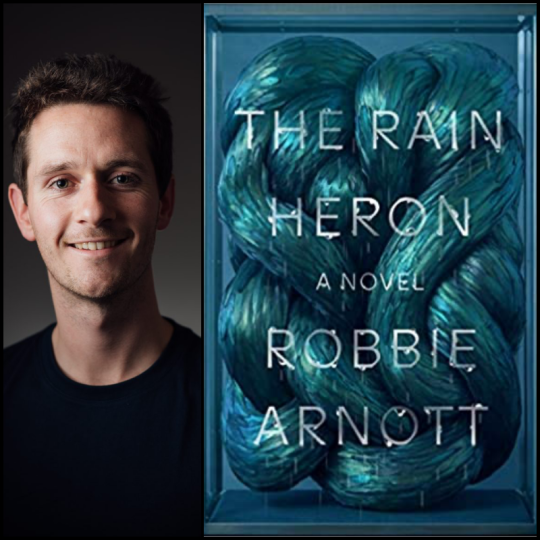

Searching for Peace and a Mythical Bird in Robbie Arnott’s The Rain Heron

At the end of its life, the phoenix bursts into flames and a younger bird rises from the ashes. The roc is large enough to carry an elephant in its claws. The caladrius absorbs disease, curing the ill. The rain heron, which can take the form of steam, liquid or ice, controls the climate around it.

Unlike the first three mythical birds, whose legends are hundreds or thousands of years old, the rain heron is a new entry in the library of imaginary beasts, introduced in the novel bearing its name by Tasmanian author Robbie Arnott.

Set in an unnamed country beset by a military coup and climate disruptions, The Rain Heron is a story of survivors searching for peace but finding violence in both nature and society. The characters are tested and exposed by the titular creature, which exacts a price from those who dare covet it.

“What I was really trying to do was create a mythical creature that embodies both the beauty and the savagery of nature,” Arnott says. “I wanted something that is totally captivating, the way many natural environments and phenomena can be, but also is really, really dangerous.”

Arnott’s descriptions of nature are inspired by the beauty of his Australian home state of Tasmania, where he has spent long stretches hiking in the bush and fishing in the cold waters. “It always comes through in my writing a lot. There’s lots of descriptions of natural places because that’s generally where I’ve been and what I’m interested in. I tried living in a big city for a while and I just I just couldn’t do it.”

Robbie Arnott is the author of the novel Flames, which won the Margaret Scott Prize, was short-listed for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Prize for Fiction, the Guardian Not the Booker Prize, and the Readings Prize for New Australian Fiction. In 2019, he was named a Sydney Morning Herald Best Young Australian Novelist. The Rain Heron was one of LitHub‘s Most Anticipated Books of 202.

March 17, 2021

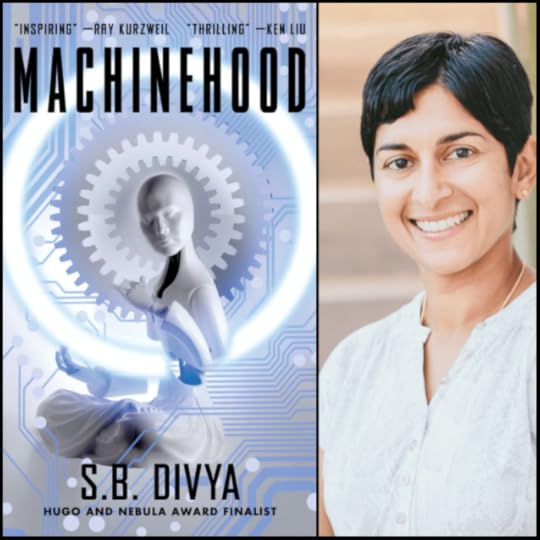

Are People and Bots Collaborating or Competing in S.B. Divya’s Machinehood?

The title of S. B. Divya’s novel Machinehood refers to an underground band of rebels (or terrorists, depending on your view) who threaten to unplug the world from the tech essential to modern life unless rights of all intelligences—human and man-made—are recognized and respected.

The book opens with Welga, the story’s hero, ordering black coffee from a bot in Chennai, India; the bot puts milk in her coffee while insisting that the drink is still “black.” A human vendor across the street fills Welga’s order properly, without milk, and then summarizes her experiences with the two vendors in a tidy lesson: “Bots work faster, but human mind is smarter.”

The vendor’s words foreshadow the fault line that runs through the book. On the one hand, humans rely on bots to run their homes and economy, on the other, humans compete with bots, constantly afraid of falling physically and mentally behind.

“Once upon a time, we harnessed animals to help us,” Divya tells me on the latest New Books in Science Fiction. “Now we’ve turned to machines and, as those machines get increasingly intelligent, the competition in certain sectors is going to also ramp up. There’s an existential fear right now for a lot of people that AIs are going to replace them and then they’re not going to have work. So in part, this novel is exploring that concern, but not so much as a dystopia, more as a realistic vision … of what the future could look like when we have to coexist with these very, very capable machines.

Set 75 years in the future, the AIs in Welga’s world have not yet achieved sentience (hence they’re referred to as “weak” AIs.) Still, they are stronger and process information faster than humans. To keep up, humans use mechanized exoskeletons to make themselves stronger and pills to speed their thinking and reflexes, greying the distinction between humans and bots.

“How much of a difference is there really between human beings, cyborgs and AI-based robots? And should we be making as much distinction between those categories as we do today, especially going forward as all of these things get more sophisticated? I was really interested in looking at the blurring of those lines and interrogating at what point we decide to give machines rights, especially when they provide us with so much free labor.”

February 25, 2021

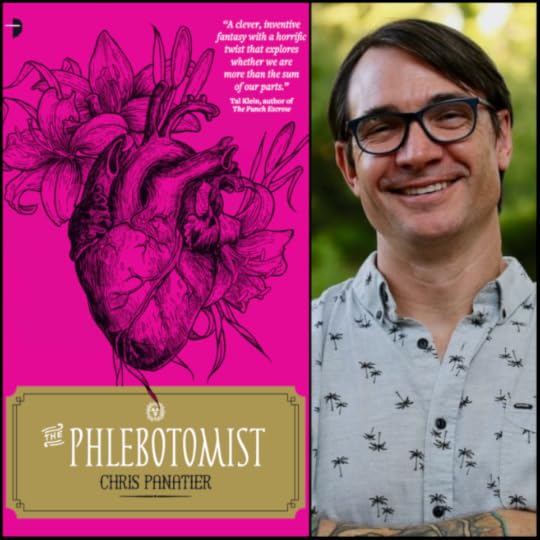

Chris Panatier’s The Phlebotomist is a Bloody Business

Humans have found many ways to divide and stratify—by skin color, ancestry, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, disability, health status, body type or size, and so on. The list is so long that it’s hard to imagine it getting longer, and yet debut author Chris Panatier has found a way. In The Phlebotomist, society is divided (as the title suggests) by something invisible to the naked eye: blood type.

Universal donors—those with Type O negative—are the most valued. Universal recipients—those who are AB positive—are the least valued. With incomes based on the market value of their blood, universal donors end up at the top of the socio-economic hierarchy and universal recipients at the bottom.

Meanwhile, those running the show—executives of the company Patriot—are the richest of all, living in exclusive enclaves. It is vampiric capitalism in more ways than one.

The name of the company is a reference to the Patriot Act—a real-life example of creeping authoritarianism that parallels the world of The Phlebotomist.

“This ubiquitous contractor, Patriot, has slowly crept into the realm of individual rights and privacy until one day, everyone wakes up, and there’s a mandatory blood draw, and they have to give blood every day and are under surveillance and tracked everywhere,” Panatier explains on New Books in Science Fiction. “All of that started as a patriotic thing to do. There was a war, people were asked to give blood, and so they proudly did it. And then slowly … people were under the boot of the government and this enigmatic contractor. … It’s a bit of an allegory for sure. … because these are things I see in our everyday lives.”

February 4, 2021

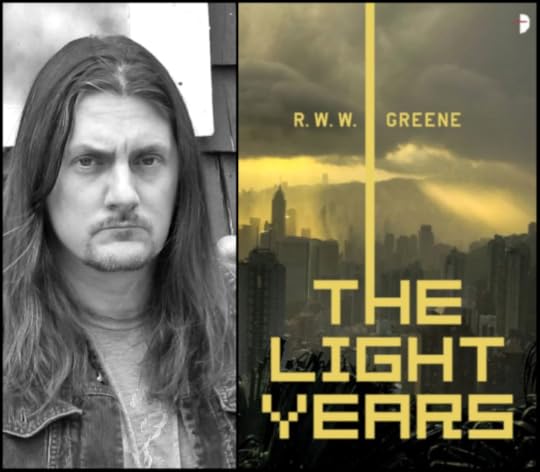

In R.W.W. Greene’s The Light Years, Arranged Marriage Finds Renewed Utility at the Speed of Light

Arranged marriages have been around for centuries, and in The Light Years, R.W.W. Greene imagines they’ll be around for centuries more.

With the addition of speed-of-light travel, Greene’s character Adem Saddiq can sign a contract with the parents of his wife-to-be before she’s even born, take to space on his family’s freighter and return several months later to find his 26-year-old bride, Hisako Sasaki, waiting for him. Because time dilation allows him to jump 26 years into the future, he can have his bride made-to-order, specifying what degrees and skills she’ll need to play a productive part in the family business. He can even require that she receive genetic modifications to make her a genius.

Greene imagines that the same considerations that shaped arranged marriages in the past will shape them in the future. Hisako’s “parents are very poor. They’re refugees,” he tells me on today’s episode of New Books in Science Fiction. “Their only way to get out of this situation is to sign the contract. It’s going to allow Adem and his family to pay for Hisako’s schooling, which she wouldn’t otherwise have gotten. It’s going to pay for a family apartment, which they wouldn’t otherwise have had. And it’s going to make sure that she has a life that’s going to be far better than her parents’.”

Understandably, Hisako sees the situation differently. “If you’re the mom and the dad, then you see [the arranged marriage] as something that would be good for your kid. If you’re the kid, your whole life has been stolen from you and preordained and pre-contracted. Like Hisako, you’d be a little pissed about it.”

The Light Years is Greene’s first novel.