Katey Schultz's Blog, page 17

June 2, 2014

Revising the Novel: Absorbing the Advice

Last week, I wrote about knowing when you need help in your novel revisions. I'm two years into the first sparks of The Longest Day of the Year and now, two editors as well. Not the kind of editor that is paid by your publishing house and coaches you through various revisions of a novel that's contractually promised a publication date and a paycheck. But the kind that comes by way of referral and is hired at the author's expense for a once-over of a manuscript-in-progress to help make that next creative leap.

Something like this, by Jalipuchi, only less vibrant and vivid.The good news is, I can see the edge of the other side of the cliff I've got to land on. In my mind's eye, it's like a historical Zen watercolor--mostly white with a few brushstrokes of green, gray, and brown to suggest a village, a deep canyon, and a distant cliff edge overlooking a gorge. I'm standing on one side of the gorge. The next creative path for my novel is on the other side. It's that far cliff edge, tucked into the clouds and almost dreamlike, that I'm aiming for. Before I hired help, I had to remind myself that the cliff edge was even there, even though I couldn't see it. Now, I can make out its outline through the fog.

Something like this, by Jalipuchi, only less vibrant and vivid.The good news is, I can see the edge of the other side of the cliff I've got to land on. In my mind's eye, it's like a historical Zen watercolor--mostly white with a few brushstrokes of green, gray, and brown to suggest a village, a deep canyon, and a distant cliff edge overlooking a gorge. I'm standing on one side of the gorge. The next creative path for my novel is on the other side. It's that far cliff edge, tucked into the clouds and almost dreamlike, that I'm aiming for. Before I hired help, I had to remind myself that the cliff edge was even there, even though I couldn't see it. Now, I can make out its outline through the fog.

A good editor is one who gives you the tools to build the bridge you need in order to get across. And if you'll let me take the analogy a beat further, that same editor will likewise understand that there's a fine balance between a writer's sense of creative entitlement and a writer's need for outside assistance. The best feedback, therefore, gives the writer the right tools and points in a possible direction ("Right over there, by that gray boulder. Maybe if you start building your bridge there, you'll make it across most efficiently," the editor might say.), but doesn't ever build the bridge for the writer.

I've re-read the letter from my editor three times. Blogging about it helps reinforce the learning and likewise persuades me to take my time. I've always wanted the end goal sooner than I was able to reach it. It's one of the things that I think has enabled me to remain disciplined and focused--but it likewise always threatens to exhaust me. Here, I have a chance to move very, very slowly--perhaps as slowly as I moved this winter--while also trusting in my process. In another week or so, I'll start drafting again, likely by hand. It's scary to think of that blank page after so many hundreds have already been written but I have to trust that those pages are inside of me--at least their emotional significance--and that better words, more characterizing, tighter, impactful words and moments will come if I give them the space lay down.

Something like this, by Jalipuchi, only less vibrant and vivid.The good news is, I can see the edge of the other side of the cliff I've got to land on. In my mind's eye, it's like a historical Zen watercolor--mostly white with a few brushstrokes of green, gray, and brown to suggest a village, a deep canyon, and a distant cliff edge overlooking a gorge. I'm standing on one side of the gorge. The next creative path for my novel is on the other side. It's that far cliff edge, tucked into the clouds and almost dreamlike, that I'm aiming for. Before I hired help, I had to remind myself that the cliff edge was even there, even though I couldn't see it. Now, I can make out its outline through the fog.

Something like this, by Jalipuchi, only less vibrant and vivid.The good news is, I can see the edge of the other side of the cliff I've got to land on. In my mind's eye, it's like a historical Zen watercolor--mostly white with a few brushstrokes of green, gray, and brown to suggest a village, a deep canyon, and a distant cliff edge overlooking a gorge. I'm standing on one side of the gorge. The next creative path for my novel is on the other side. It's that far cliff edge, tucked into the clouds and almost dreamlike, that I'm aiming for. Before I hired help, I had to remind myself that the cliff edge was even there, even though I couldn't see it. Now, I can make out its outline through the fog.A good editor is one who gives you the tools to build the bridge you need in order to get across. And if you'll let me take the analogy a beat further, that same editor will likewise understand that there's a fine balance between a writer's sense of creative entitlement and a writer's need for outside assistance. The best feedback, therefore, gives the writer the right tools and points in a possible direction ("Right over there, by that gray boulder. Maybe if you start building your bridge there, you'll make it across most efficiently," the editor might say.), but doesn't ever build the bridge for the writer.

I've re-read the letter from my editor three times. Blogging about it helps reinforce the learning and likewise persuades me to take my time. I've always wanted the end goal sooner than I was able to reach it. It's one of the things that I think has enabled me to remain disciplined and focused--but it likewise always threatens to exhaust me. Here, I have a chance to move very, very slowly--perhaps as slowly as I moved this winter--while also trusting in my process. In another week or so, I'll start drafting again, likely by hand. It's scary to think of that blank page after so many hundreds have already been written but I have to trust that those pages are inside of me--at least their emotional significance--and that better words, more characterizing, tighter, impactful words and moments will come if I give them the space lay down.

Published on June 02, 2014 05:00

May 29, 2014

Moral Confusion & the Iraq War

Please take a moment today to read author and journalist Helen Benedict's insightful, new essay on the moral oxymoron of the Iraq war, and how veterans and civilians alike might go forth in personal introspection and moving forward.

Read my interview with Helen here.

Read my interview with Helen here.

An excerpt from Guernica's full publication of the essay:

“Your army came to my country and destroyed it,” [Iraq author Hassan Blasin] said, arms crossed, eyes calm. “Your war has not only destroyed this generation, it has destroyed generations of Iraqis’ futures. And you don’t even say you’re sorry.”Silence. Some visible squirming. But no apologies.What if we had said sorry? What if everyone in the audience, the veterans included, had stood up and said, “Hassan Blasim, we are sorry for wrecking your country and killing your family and friends. We were wrong.”? I doubt our apology would do much for Blasim or his fellow Iraqis, other than show them long overdue respect. And we certainly shouldn’t ask for forgiveness; that would be audacious and absurd, but it might help clear up the divisions of the soul that the Iraq War has produced in so many of us.The silence in Barnes and Noble—the fact that none of us, myself included, stood up and said, “I’m sorry,” although I’m sure many of us are—exposed our moral confusion for what it is. Because, just as veterans are trying to ignore the glaring contradictions between being ashamed of participating in the Iraq War and being proud of it, so are we citizens. We are all implicated in this bitter paradox, whatever our politics. Yes, veterans are on the front lines of this moral battle, but we civilians are the ones who put them there—with our votes and tax money, and with our policies that drive so many boys and girls from poverty into the military to make a living or to pay for college. We are all culpable. And like so many veterans, we—our media, our government, all of us—are having a terrible time asking honest questions of ourselves about the Iraq War, or answering Blasim’s challenge to face up to what we did and apologize.

Read my interview with Helen here.

Read my interview with Helen here.

An excerpt from Guernica's full publication of the essay:

“Your army came to my country and destroyed it,” [Iraq author Hassan Blasin] said, arms crossed, eyes calm. “Your war has not only destroyed this generation, it has destroyed generations of Iraqis’ futures. And you don’t even say you’re sorry.”Silence. Some visible squirming. But no apologies.What if we had said sorry? What if everyone in the audience, the veterans included, had stood up and said, “Hassan Blasim, we are sorry for wrecking your country and killing your family and friends. We were wrong.”? I doubt our apology would do much for Blasim or his fellow Iraqis, other than show them long overdue respect. And we certainly shouldn’t ask for forgiveness; that would be audacious and absurd, but it might help clear up the divisions of the soul that the Iraq War has produced in so many of us.The silence in Barnes and Noble—the fact that none of us, myself included, stood up and said, “I’m sorry,” although I’m sure many of us are—exposed our moral confusion for what it is. Because, just as veterans are trying to ignore the glaring contradictions between being ashamed of participating in the Iraq War and being proud of it, so are we citizens. We are all implicated in this bitter paradox, whatever our politics. Yes, veterans are on the front lines of this moral battle, but we civilians are the ones who put them there—with our votes and tax money, and with our policies that drive so many boys and girls from poverty into the military to make a living or to pay for college. We are all culpable. And like so many veterans, we—our media, our government, all of us—are having a terrible time asking honest questions of ourselves about the Iraq War, or answering Blasim’s challenge to face up to what we did and apologize.

Published on May 29, 2014 05:45

May 26, 2014

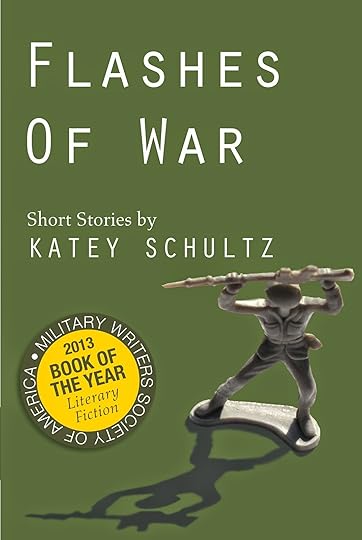

Celebrating One Year: Review Flashes of War on Amazon

Dear Friends,

Dear Friends,Tuesday, May 27th marks the one-year anniversary of the publication of Flashes of War. In celebration, I'm dubbing this day BOOK EVENT #52 and conducting it from the quiet of my own home. It's astonishing to imagine I averaged one book event a week for a year of self-funded tour. After this day, I'm officially done counting. For BOOK EVENT #52, I ask one thing:

Please take a moment right now and rate or review my book on Amazon. Although I've been fortunate to receive dozens of positive reviews from literary and military publications, an inconceivable amount of a book's success is dependent upon corporate giant Amazon. If you have read and enjoyed my book, please use the link below to write a review or rate the book:

http://www.amazon.com/Flashes-War-Stories-Katey-Schultz/dp/1934074853/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1401147536&sr=1-1&keywords=flashes+of+war

Acting within the same short window of time, your reviews will have an even greater impact on Amazon ratings and directly influence others considering making a purchase. If you're moved to assist further, please spread the word, consider Flashes of War for your book club, or purchase a copy of the book as a gift (such as Father's Day).

The words "thank you" simply do not suffice as an offering to all of you who have rooted for, housed, fed, hosted, and helped me along the way.

In all sincerest gratitude,

Katey

PS If you're looking for specifics to share, here is the link to the 7-minute NPR Morning Edition regional spotlight interview (http://wncw.org/post/morning-edition-friday-sept-6-flashes-war-katey-schultz) and here is a blurb that speaks to the heart of my intentions for the work: “This is a brilliant, unsettling, and disturbingly beautiful book…Writing of this degree of commitment and integrity is living evidence of the power of fiction to tell the truth about reality.” –Joydeep Roy-Bhattacharya (The Watch)

Published on May 26, 2014 16:54

May 22, 2014

Revising the Novel: Knowing When You Need Help

If the writing life wasn't also my career...

If the success of a first book wasn't a platform for a second book...

If I didn't need an advance to jump-start my next-step life objectives (ex. owning a house, growing a retirement fund, planning a honeymoon)...

If a self-funded, cross-country book tour was something I'd ever do again...

...then I could take my sweet time with this novel. I could spend, perhaps, ten years coming to it and leaving it alone as life dictated, eventually considering submitting to a smaller press regardless of whether or not I lost or made money.

But none of those things are true; not for me and not anytime soon unless I have a major change of heart and shift in my life focus. I chose this pressure and these parameters just like I pointedly understood I was not going to graduate school in order to become a full-time professor. Full-time writer, yes. Full-time teacher...wasn't that the job I left in order to write more? Yes, yes it was.

To that end, I've hired help for my novel. I received professional feedback in August of 2013 that was curt, condescending, and occasionally accurate. The former two left me hollow (and I've got seriously tough skin, let me tell you--you don't live out of your car for 3 years and get 44 rejections from presses and over 50 rejections from fellowships without getting tough skin), the last left me hopeful but also slightly directionless. I muddled through that, in thanks to many hours of self-designed study plans and Wonderbook, finally handing over 1/3 of the newly revised work last month to an agent I thought might make my dreams come true.

Dreams are dreams for a reason, though, and while mine certainly motivated me for many months to get the work done, I also received a hearty reality check when that agent made it clear once and for all that my plot sucks eggs. Among other things.

Time to hire more help, and this time I found someone with expertise in narrative exposition (my weak spot) who was likewise affordable and kind, while also not beating around the bush. Her feedback was diagnostic and prescriptive, inspiring me to step back and consider starting over with a new vision; the kind of feedback that sends writers back to the page, rather than running from it.

All of which is to say that, although writing may be a "solo sport" during the actual toosh-in-chair time, knowing when you need help and investing in that help (and therefore in yourself, your passions) is crucial to success. I know my limits. I'd taken the lessons from my last editor as far as I could take them and improved some things, but other large problems still loomed. I knew enough to know they were there, but not how to fix them. This most recent help doesn't have all the answers, but she's set me up for success in this next go-round and that's priceless.

I might have been able to teach myself what she taught me with two, three, or four years of self-study and reflection, but I don't have that kind of time and I know it. In the coming months, as I work through her tips and my own kinks in the creative process, I hope to share some of what I'm learning along the way. Meantime, I'm still processing and trying to let the feedback seep in deeply--as deep as possibly--as I regather and reorient for this next great leap.

If the success of a first book wasn't a platform for a second book...

If I didn't need an advance to jump-start my next-step life objectives (ex. owning a house, growing a retirement fund, planning a honeymoon)...

If a self-funded, cross-country book tour was something I'd ever do again...

...then I could take my sweet time with this novel. I could spend, perhaps, ten years coming to it and leaving it alone as life dictated, eventually considering submitting to a smaller press regardless of whether or not I lost or made money.

But none of those things are true; not for me and not anytime soon unless I have a major change of heart and shift in my life focus. I chose this pressure and these parameters just like I pointedly understood I was not going to graduate school in order to become a full-time professor. Full-time writer, yes. Full-time teacher...wasn't that the job I left in order to write more? Yes, yes it was.

To that end, I've hired help for my novel. I received professional feedback in August of 2013 that was curt, condescending, and occasionally accurate. The former two left me hollow (and I've got seriously tough skin, let me tell you--you don't live out of your car for 3 years and get 44 rejections from presses and over 50 rejections from fellowships without getting tough skin), the last left me hopeful but also slightly directionless. I muddled through that, in thanks to many hours of self-designed study plans and Wonderbook, finally handing over 1/3 of the newly revised work last month to an agent I thought might make my dreams come true.

Dreams are dreams for a reason, though, and while mine certainly motivated me for many months to get the work done, I also received a hearty reality check when that agent made it clear once and for all that my plot sucks eggs. Among other things.

Time to hire more help, and this time I found someone with expertise in narrative exposition (my weak spot) who was likewise affordable and kind, while also not beating around the bush. Her feedback was diagnostic and prescriptive, inspiring me to step back and consider starting over with a new vision; the kind of feedback that sends writers back to the page, rather than running from it.

All of which is to say that, although writing may be a "solo sport" during the actual toosh-in-chair time, knowing when you need help and investing in that help (and therefore in yourself, your passions) is crucial to success. I know my limits. I'd taken the lessons from my last editor as far as I could take them and improved some things, but other large problems still loomed. I knew enough to know they were there, but not how to fix them. This most recent help doesn't have all the answers, but she's set me up for success in this next go-round and that's priceless.

I might have been able to teach myself what she taught me with two, three, or four years of self-study and reflection, but I don't have that kind of time and I know it. In the coming months, as I work through her tips and my own kinks in the creative process, I hope to share some of what I'm learning along the way. Meantime, I'm still processing and trying to let the feedback seep in deeply--as deep as possibly--as I regather and reorient for this next great leap.

Published on May 22, 2014 05:00

May 19, 2014

#Airstream Living: Seasonal Master Bedroom

Dear Martha Stewart,

Aren't you proud? All this on a shoestring...and I've quadrupled my bedroom square footage! I personally thought the white Christmas lights were a nice touch at night...And seeing as how I'm recently engaged and my fiance moves in today, we're quite pleased with the results:

Our new seasonal master bedroom isn't technically in my Airstream, but in the spirit of Airstream's founder Wally Byam, this 14' x 9' tent on a raised platform complete with nearby campfire ring, outdoor picnic area, and neighboring mountains and streams fits his creed in part: "To place the great wide world at your doorstep for you who yearn to travel with all the comforts of home...to strive endlessly to stir the venturesome spirit that moves you to follow a rainbow to its end and thus make your [travel] dreams come true." (Read Byam's full creed here.)

Our new seasonal master bedroom isn't technically in my Airstream, but in the spirit of Airstream's founder Wally Byam, this 14' x 9' tent on a raised platform complete with nearby campfire ring, outdoor picnic area, and neighboring mountains and streams fits his creed in part: "To place the great wide world at your doorstep for you who yearn to travel with all the comforts of home...to strive endlessly to stir the venturesome spirit that moves you to follow a rainbow to its end and thus make your [travel] dreams come true." (Read Byam's full creed here.)

Note the "nightstands" contain Peterson's field guide to Eastern Birds, Poetry of the Birds anthology, binoculars, tissues, crossword puzzles, and a deck of cards. Side pockets include one headlamp each. Tarps on the left will be hung over the tent extending well beyond the perimeter of the platform to create a dry space for taking off shoes. On the right is a hanging coat rack for essentials moving to and from the master bedroom to the Airstream.

Note the "nightstands" contain Peterson's field guide to Eastern Birds, Poetry of the Birds anthology, binoculars, tissues, crossword puzzles, and a deck of cards. Side pockets include one headlamp each. Tarps on the left will be hung over the tent extending well beyond the perimeter of the platform to create a dry space for taking off shoes. On the right is a hanging coat rack for essentials moving to and from the master bedroom to the Airstream.

Oh, and there's even enough space for abs & arms!We're not sure where or how we'll be set up for Fall and Winter (all depending on Brad's clinical site for grad school), but in the very least it will likely involve some mix of time at his place in rural southwest Virginia and weekends in Celo...with a mutual goal for full-time living in our coveted South Toe Valley in the coming years.

Oh, and there's even enough space for abs & arms!We're not sure where or how we'll be set up for Fall and Winter (all depending on Brad's clinical site for grad school), but in the very least it will likely involve some mix of time at his place in rural southwest Virginia and weekends in Celo...with a mutual goal for full-time living in our coveted South Toe Valley in the coming years.

What's that you say, Martha? You've never seen the South Toe River? Tisk, tisk! Consider this your invitation. My tent door is always open! And don't forget to pack your Crocs for the river!

Katey

Aren't you proud? All this on a shoestring...and I've quadrupled my bedroom square footage! I personally thought the white Christmas lights were a nice touch at night...And seeing as how I'm recently engaged and my fiance moves in today, we're quite pleased with the results:

Our new seasonal master bedroom isn't technically in my Airstream, but in the spirit of Airstream's founder Wally Byam, this 14' x 9' tent on a raised platform complete with nearby campfire ring, outdoor picnic area, and neighboring mountains and streams fits his creed in part: "To place the great wide world at your doorstep for you who yearn to travel with all the comforts of home...to strive endlessly to stir the venturesome spirit that moves you to follow a rainbow to its end and thus make your [travel] dreams come true." (Read Byam's full creed here.)

Our new seasonal master bedroom isn't technically in my Airstream, but in the spirit of Airstream's founder Wally Byam, this 14' x 9' tent on a raised platform complete with nearby campfire ring, outdoor picnic area, and neighboring mountains and streams fits his creed in part: "To place the great wide world at your doorstep for you who yearn to travel with all the comforts of home...to strive endlessly to stir the venturesome spirit that moves you to follow a rainbow to its end and thus make your [travel] dreams come true." (Read Byam's full creed here.) Note the "nightstands" contain Peterson's field guide to Eastern Birds, Poetry of the Birds anthology, binoculars, tissues, crossword puzzles, and a deck of cards. Side pockets include one headlamp each. Tarps on the left will be hung over the tent extending well beyond the perimeter of the platform to create a dry space for taking off shoes. On the right is a hanging coat rack for essentials moving to and from the master bedroom to the Airstream.

Note the "nightstands" contain Peterson's field guide to Eastern Birds, Poetry of the Birds anthology, binoculars, tissues, crossword puzzles, and a deck of cards. Side pockets include one headlamp each. Tarps on the left will be hung over the tent extending well beyond the perimeter of the platform to create a dry space for taking off shoes. On the right is a hanging coat rack for essentials moving to and from the master bedroom to the Airstream. Oh, and there's even enough space for abs & arms!We're not sure where or how we'll be set up for Fall and Winter (all depending on Brad's clinical site for grad school), but in the very least it will likely involve some mix of time at his place in rural southwest Virginia and weekends in Celo...with a mutual goal for full-time living in our coveted South Toe Valley in the coming years.

Oh, and there's even enough space for abs & arms!We're not sure where or how we'll be set up for Fall and Winter (all depending on Brad's clinical site for grad school), but in the very least it will likely involve some mix of time at his place in rural southwest Virginia and weekends in Celo...with a mutual goal for full-time living in our coveted South Toe Valley in the coming years.What's that you say, Martha? You've never seen the South Toe River? Tisk, tisk! Consider this your invitation. My tent door is always open! And don't forget to pack your Crocs for the river!

Katey

Published on May 19, 2014 04:41

May 15, 2014

Farewell to THE CLAW

I guess when big life changes happen, there can be a ripple effect. The same day I bought the new-to-me 2007 Toyota Prius that's now my sole vehicle, Brad proposed. I had no idea the proposal was coming, of course, so I was already pretty emotionally spent from the process of signing away more money to a single object than I've ever paid in my life (but excited, too). Being engaged offered a total energy surge--What new car? What money? What stress? Who cares! We're getting married!--and we spent that evening with Brad's family and extended family (who showed up with a jar of moonshine).

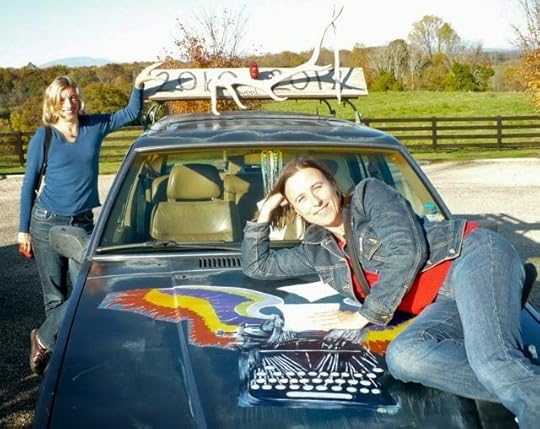

Needless to say, parting with THE CLAW was bittersweet. I've driven this 1989 Volvo Station Wagon 740GL for 7 years. Half of that time, this car was my home. No exaggeration there. My home. (If you have any doubts, visit this page.) I have driven THE CLAW across the country and back 3 times, driven it 4 times to and from NC and northern Michigan, and even been featured in an interview regarding THE CLAW's superior powers. This car has been through a cattle drive; over 9,000 foot mountain passes (at a crawl); through the Pigeon River Gorge in a blizzard; through a Texas drought which involved 58 consecutive days of no rain and temps over 100 degrees (without air conditioning); journeyed along the Bourbon Trail in Kentucky; and so much more. It has parked at somewhere around a dozen artist retreat havens across the United States and ferried backpackers to trailheads near and far. It has blasted Pearl Jam when I needed to stay awake, The Pines when I was heart-sick, Andrew Bird for countless hours, and Death Cab for Cutie when I needed nostalgia.

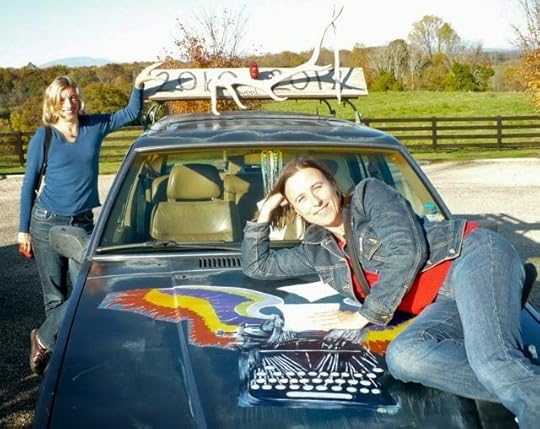

Most of all, THE CLAW has served as a metaphor for going after life. Claws grab what they want. They see something and go for it. The antlers came along later, and of course the final, completing decoration was the typewriter with wings painted across the hood. Here are a few sweet memories in photos. Farewell sweet home, badass friend, and protector of all deeds writerly and road-bound:

Interlochen Center for the Arts

Interlochen Center for the Arts

Yes, THE CLAW is in this photo!

Yes, THE CLAW is in this photo!

Weymouth Center for Arts & Humanities

Weymouth Center for Arts & Humanities

The morning after the Pigeon River Gorge blizzard.

The morning after the Pigeon River Gorge blizzard.

Imnaha River Canyon, OR

Imnaha River Canyon, OR

Wallowa Mountains, OR

Wallowa Mountains, OR

Portland!

Portland!

Authors and friends John & Julie Rember add elk antlers from Idaho.

Authors and friends John & Julie Rember add elk antlers from Idaho.

Printmaker Maranda Allbritten ties a streamer on...

Printmaker Maranda Allbritten ties a streamer on...

Poet Mendy Knott meets THE CLAW in Arkansas.

Poet Mendy Knott meets THE CLAW in Arkansas.

The ranch handler at Madrono Artist Residency in south-central Texas added these...and then the fawn came along.

The ranch handler at Madrono Artist Residency in south-central Texas added these...and then the fawn came along.

Painter Gavin Post adds the esteemed typewriter to the hood.

Painter Gavin Post adds the esteemed typewriter to the hood.

German author Barbara Krohn and German painter Ingrid Floss adorn THE CLAW in Virginia.

German author Barbara Krohn and German painter Ingrid Floss adorn THE CLAW in Virginia.

Road trip to best friends in Milwaukie, WI![ad infinitum...]

Road trip to best friends in Milwaukie, WI![ad infinitum...]

Needless to say, parting with THE CLAW was bittersweet. I've driven this 1989 Volvo Station Wagon 740GL for 7 years. Half of that time, this car was my home. No exaggeration there. My home. (If you have any doubts, visit this page.) I have driven THE CLAW across the country and back 3 times, driven it 4 times to and from NC and northern Michigan, and even been featured in an interview regarding THE CLAW's superior powers. This car has been through a cattle drive; over 9,000 foot mountain passes (at a crawl); through the Pigeon River Gorge in a blizzard; through a Texas drought which involved 58 consecutive days of no rain and temps over 100 degrees (without air conditioning); journeyed along the Bourbon Trail in Kentucky; and so much more. It has parked at somewhere around a dozen artist retreat havens across the United States and ferried backpackers to trailheads near and far. It has blasted Pearl Jam when I needed to stay awake, The Pines when I was heart-sick, Andrew Bird for countless hours, and Death Cab for Cutie when I needed nostalgia.

Most of all, THE CLAW has served as a metaphor for going after life. Claws grab what they want. They see something and go for it. The antlers came along later, and of course the final, completing decoration was the typewriter with wings painted across the hood. Here are a few sweet memories in photos. Farewell sweet home, badass friend, and protector of all deeds writerly and road-bound:

Interlochen Center for the Arts

Interlochen Center for the Arts Yes, THE CLAW is in this photo!

Yes, THE CLAW is in this photo! Weymouth Center for Arts & Humanities

Weymouth Center for Arts & Humanities The morning after the Pigeon River Gorge blizzard.

The morning after the Pigeon River Gorge blizzard. Imnaha River Canyon, OR

Imnaha River Canyon, OR Wallowa Mountains, OR

Wallowa Mountains, OR Portland!

Portland! Authors and friends John & Julie Rember add elk antlers from Idaho.

Authors and friends John & Julie Rember add elk antlers from Idaho. Printmaker Maranda Allbritten ties a streamer on...

Printmaker Maranda Allbritten ties a streamer on... Poet Mendy Knott meets THE CLAW in Arkansas.

Poet Mendy Knott meets THE CLAW in Arkansas. The ranch handler at Madrono Artist Residency in south-central Texas added these...and then the fawn came along.

The ranch handler at Madrono Artist Residency in south-central Texas added these...and then the fawn came along. Painter Gavin Post adds the esteemed typewriter to the hood.

Painter Gavin Post adds the esteemed typewriter to the hood. German author Barbara Krohn and German painter Ingrid Floss adorn THE CLAW in Virginia.

German author Barbara Krohn and German painter Ingrid Floss adorn THE CLAW in Virginia. Road trip to best friends in Milwaukie, WI![ad infinitum...]

Road trip to best friends in Milwaukie, WI![ad infinitum...]

Published on May 15, 2014 05:00

May 12, 2014

An Engaging Weekend

I know I'm a writer but sometimesa picture really is worth a thousand words...

Or maybe just one:YES!

Or maybe just one:YES!

Published on May 12, 2014 04:00

May 8, 2014

Ernest Hemingway: An Interview in The Paris Review, circa 1958

I don't know very many writers who can go over to their parents' house and say, "Hey Dad, you know that one famous interview Hemingway gave in The Paris Review? I've never read it but people often talk about it. Do you have it?"

Of course Dad has it.

He has all the books that matter--and the most important editions are wrapped in plastic, stored on one of two special shelves, categorized separate from the fiction and poetry in the living room (which are organized roughly alphabetically, with notable exceptions such as Wendell Berry and Jim Harrison whose books--no matter the genre--all belong next to each other on the same shelf, crammed close like siblings aligned for a family photograph).

Never mind that the interview I was looking for was published in 1958, when Dad was...um...a third grader. Never mind that I grew up surrounded by his collections and still don't understand how freaking awesome its contents are. Within about 40 seconds, Dad has found the desired copy of The Paris Review and handed it over, like no big deal. (I won't tell you the price he paid in 1996 when he finally found the coveted back issue and added it to his collection; suffice it to say that in 1958 it sold for $1 or 250 francs.)

Here are some choice excerpts:

Here are some choice excerpts:

Interviewer: Is emotional stability necessary to write well? You told me once that you could only write well when you were in love. Could you expound on that a bit more?

HEMINGWAY: What a question. But full marks for trying. You can write any time people will leave you alone and not interrupt you. Or rather you can if you will be ruthless enough about it. But the best writing is certainly when you are in love. If it is all the same to you I would rather not expound on that.

Interviewer: How about financial security? Can that be a detriment to good writing?

HEMINGWAY: If it came early and you loved life as much as you loved your work it would take much character to resist the temptations. Once writing has become your major vice and greatest pleasure only death can stop it. Financial security then is a great help as it keeps you from worrying. Worry destroys the ability to write. Ill health is bad in the ratio that it produces worry which attacks your subconscious and destroys your reserves.

Interviewer: What would you consider the best intellectual training for the would-be writer?

HEMINGWAY: Let's say that he should go out and hang himself because he finds that writing well is impossibly difficult. Then he should be cut down without mercy and forced by his own self to write as well as he can for the rest of his life. At least he will have the story of the hanging to commence with.

Interviewer: You seem to have avoided the company of writers in late years. Why?

HEMINGWAY: That is more complicated. The further you go in writing the more alone you are. Most of your best and oldest friends die. Others move away. You do not see them except rarely, but you write and have much the same contact with them as though you were together at the cafe in the old days. You exchange comic, sometimes cheerfully obscene and irresponsible letters, and it is almost as good as talking. But you are more alone because that is how you must work and the time to work is shorter all the time and if you waste it you feel you have committed a sin for which there is no forgiveness.

Interviewer: So when you're not writing, you remain constantly the observer, looking for something which can be of use.

HEMINGWAY: Surely. If a writer stops observing he is finished. But he does not have to observe consciously nor think how it will be useful. Perhaps that would be true at the beginning. But later everything he sees goes into the great reserve of things he knows or has seen. If it is any use to know it, I always try to write on the principle of the iceberg. There is seven-eighths of it underwater for every part that shows. Anything you know you can eliminated and it only strengthens your iceberg. It is the part that doesn't show. If a writer omits something because he does not know it then there is a hole in the story....

Anyway, to skip how [The Old Man and the Sea] is done, I had unbelievable luck this time and could convey the experience completely and have it be one that no one had ever conveyed. The luck was that I had a good man and a good boy and lately writers have forgotten there still are such things. Then the ocean is worth writing about just as man is. So I was lucky there. I've seen the marlin mate and know about that. So I leave that out. I've seen a school (or pod) of more than fifty sperm whales in that same stretch of water and once harpooned one nearly sixty feet in length and lost him. So I left that out. All the stories I know from the fishing village I leave out. But the knowledge is what makes the underwater part of the iceberg.

Interviewer: Finally, a fundamental question: namely, as a creative writer what do you think is the function of your art? Why a representation of fact, rather than fact itself?

HEMINGWAY: Why be puzzled by that? From things that have happened and from things as they exist and from all things that you know and all those that you cannot know, you make something through your invention that is not a representation but a whole new thing truer than anything true and alive, and you make it alive, and if you make it well enough, you give it immortality. That is why you write and for no other reason that you know of. But what bout all the reasons that no one knows?

Of course Dad has it.

He has all the books that matter--and the most important editions are wrapped in plastic, stored on one of two special shelves, categorized separate from the fiction and poetry in the living room (which are organized roughly alphabetically, with notable exceptions such as Wendell Berry and Jim Harrison whose books--no matter the genre--all belong next to each other on the same shelf, crammed close like siblings aligned for a family photograph).

Never mind that the interview I was looking for was published in 1958, when Dad was...um...a third grader. Never mind that I grew up surrounded by his collections and still don't understand how freaking awesome its contents are. Within about 40 seconds, Dad has found the desired copy of The Paris Review and handed it over, like no big deal. (I won't tell you the price he paid in 1996 when he finally found the coveted back issue and added it to his collection; suffice it to say that in 1958 it sold for $1 or 250 francs.)

Here are some choice excerpts:

Here are some choice excerpts:Interviewer: Is emotional stability necessary to write well? You told me once that you could only write well when you were in love. Could you expound on that a bit more?

HEMINGWAY: What a question. But full marks for trying. You can write any time people will leave you alone and not interrupt you. Or rather you can if you will be ruthless enough about it. But the best writing is certainly when you are in love. If it is all the same to you I would rather not expound on that.

Interviewer: How about financial security? Can that be a detriment to good writing?

HEMINGWAY: If it came early and you loved life as much as you loved your work it would take much character to resist the temptations. Once writing has become your major vice and greatest pleasure only death can stop it. Financial security then is a great help as it keeps you from worrying. Worry destroys the ability to write. Ill health is bad in the ratio that it produces worry which attacks your subconscious and destroys your reserves.

Interviewer: What would you consider the best intellectual training for the would-be writer?

HEMINGWAY: Let's say that he should go out and hang himself because he finds that writing well is impossibly difficult. Then he should be cut down without mercy and forced by his own self to write as well as he can for the rest of his life. At least he will have the story of the hanging to commence with.

Interviewer: You seem to have avoided the company of writers in late years. Why?

HEMINGWAY: That is more complicated. The further you go in writing the more alone you are. Most of your best and oldest friends die. Others move away. You do not see them except rarely, but you write and have much the same contact with them as though you were together at the cafe in the old days. You exchange comic, sometimes cheerfully obscene and irresponsible letters, and it is almost as good as talking. But you are more alone because that is how you must work and the time to work is shorter all the time and if you waste it you feel you have committed a sin for which there is no forgiveness.

Interviewer: So when you're not writing, you remain constantly the observer, looking for something which can be of use.

HEMINGWAY: Surely. If a writer stops observing he is finished. But he does not have to observe consciously nor think how it will be useful. Perhaps that would be true at the beginning. But later everything he sees goes into the great reserve of things he knows or has seen. If it is any use to know it, I always try to write on the principle of the iceberg. There is seven-eighths of it underwater for every part that shows. Anything you know you can eliminated and it only strengthens your iceberg. It is the part that doesn't show. If a writer omits something because he does not know it then there is a hole in the story....

Anyway, to skip how [The Old Man and the Sea] is done, I had unbelievable luck this time and could convey the experience completely and have it be one that no one had ever conveyed. The luck was that I had a good man and a good boy and lately writers have forgotten there still are such things. Then the ocean is worth writing about just as man is. So I was lucky there. I've seen the marlin mate and know about that. So I leave that out. I've seen a school (or pod) of more than fifty sperm whales in that same stretch of water and once harpooned one nearly sixty feet in length and lost him. So I left that out. All the stories I know from the fishing village I leave out. But the knowledge is what makes the underwater part of the iceberg.

Interviewer: Finally, a fundamental question: namely, as a creative writer what do you think is the function of your art? Why a representation of fact, rather than fact itself?

HEMINGWAY: Why be puzzled by that? From things that have happened and from things as they exist and from all things that you know and all those that you cannot know, you make something through your invention that is not a representation but a whole new thing truer than anything true and alive, and you make it alive, and if you make it well enough, you give it immortality. That is why you write and for no other reason that you know of. But what bout all the reasons that no one knows?

Published on May 08, 2014 05:00

May 5, 2014

Revising the Novel: What is Your Vision?

On the heels of writing my first-ever synopsis of my novel, another request came: What is your vision for the novel? I can't post my synopsis, as that would be a bit ill-advised while still trying to get it sold, but I can post my attempt at explaining my vision. This is informal and written for an editor friend, but perhaps it will be of use to other novelists out there. I certainly learned something about my own work and creative desires by writing it--as you'll see I even slipped out of "vision" mode and into "questioning" mode in several paragraphs. These questions flowed freely, however, and now I have some sense for what I'm still grappling with.

THE LONGEST DAY OF THE YEAR

Vision for the Work

Personal curiosity: I’m interested in exploring how soldiers and civilians behave during wartime when they have no choice but to fulfill the roles they’re given. What decisions do those characters make, knowing they can do everything right and still be wrong? How do our circumstances bully us, little by little, into tremendous personal change? As each character’s arc progresses, I like to think they reach an apex of exhaustion with their given/forced roles and realize they can, in fact choose a slightly different course. That said, for the characters in The Longest Day of the Year, even as these realizations occur, it is still apparent that the forces of war are greater than any individual epiphanies its constituents reach. Despite their honest efforts and hard-earned personal growth, injustice remains a fact of war, regardless of whatever outcomes they choose for themselves. They must go on, and each of them should come to realize that for the better by the end of the novel. Does this curiosity and belief allow for enough agency to keep readers interested, or is it too subtle to highlight against the loud backdrop of war?

Creative struggle: I’m challenged by this novel because it takes place in one day, with a second narrative creeping up in time from three weeks prior. From the beginning, I have known how the novel would end—that closing scene in the road utterly crystal clear in my mind. Not long after, I thought of the orphan boy and, shortly after that, realized Aaseya was meant to adopt him. As I drafted Nathan’s sections of the novel, Folson grew in significance and, later, I knew he would be the one to die because Nathan sees a chance for his own redemption through Folson, however oddly. Folson’s death denies Nathan the redemption he thought he would have, forcing Nathan to redeem himself—a truer and perhaps better ending, even though it cost a life. While I’m open to change, I’m not sure how to do that without creating more problems for myself. If I already have too much flashback and backstory, how will compressing the Afghan narrative into one day make that problem less of an issue? If I’m struggling to get Nathan’s arc fully developed in one day of present action, how could I achieve something satisfying for Aaseya and Rahim in such short timeframe, as well?

Genre/theme curiosity: I want to write a novel that contributes to literary fiction as well as its subgenre of “war lit.” I’d like to think The Longest Day of the Year can shed light on something that hasn’t been looked at too closely by other war lit authors. I’m attempting to do this on two levels: First, by way of the based-on-fact subplot pertaining to the 2009 movement of American cash from the U.S. Government and into the hands of the Taliban, and the change in rules of engagement handed down by McChrystal, also in 2009. Second, by including the civilians’ stories (Aaseya and Rahim) and drawing interesting parallels between their desires and the desires of their “enemies” (the Americans; Nathan, Tenley). Are these parallels realized? I feel the seeds are there, but the connections aren’t as alive on the page as they could be. When I finished writing Flashes of War I could say one thing very definitively: War is complicated; the line of blame can never be traced back to one, single point. I’m still exploring that truth in The Longest Day of the Year. Can I show the complexity of this truth on a human level that transcends war, gender, culture, and circumstance? Can I show it in a way that reveals our common humanity? That’s what I want to do.

THE LONGEST DAY OF THE YEAR

Vision for the Work

Personal curiosity: I’m interested in exploring how soldiers and civilians behave during wartime when they have no choice but to fulfill the roles they’re given. What decisions do those characters make, knowing they can do everything right and still be wrong? How do our circumstances bully us, little by little, into tremendous personal change? As each character’s arc progresses, I like to think they reach an apex of exhaustion with their given/forced roles and realize they can, in fact choose a slightly different course. That said, for the characters in The Longest Day of the Year, even as these realizations occur, it is still apparent that the forces of war are greater than any individual epiphanies its constituents reach. Despite their honest efforts and hard-earned personal growth, injustice remains a fact of war, regardless of whatever outcomes they choose for themselves. They must go on, and each of them should come to realize that for the better by the end of the novel. Does this curiosity and belief allow for enough agency to keep readers interested, or is it too subtle to highlight against the loud backdrop of war?

Creative struggle: I’m challenged by this novel because it takes place in one day, with a second narrative creeping up in time from three weeks prior. From the beginning, I have known how the novel would end—that closing scene in the road utterly crystal clear in my mind. Not long after, I thought of the orphan boy and, shortly after that, realized Aaseya was meant to adopt him. As I drafted Nathan’s sections of the novel, Folson grew in significance and, later, I knew he would be the one to die because Nathan sees a chance for his own redemption through Folson, however oddly. Folson’s death denies Nathan the redemption he thought he would have, forcing Nathan to redeem himself—a truer and perhaps better ending, even though it cost a life. While I’m open to change, I’m not sure how to do that without creating more problems for myself. If I already have too much flashback and backstory, how will compressing the Afghan narrative into one day make that problem less of an issue? If I’m struggling to get Nathan’s arc fully developed in one day of present action, how could I achieve something satisfying for Aaseya and Rahim in such short timeframe, as well?

Genre/theme curiosity: I want to write a novel that contributes to literary fiction as well as its subgenre of “war lit.” I’d like to think The Longest Day of the Year can shed light on something that hasn’t been looked at too closely by other war lit authors. I’m attempting to do this on two levels: First, by way of the based-on-fact subplot pertaining to the 2009 movement of American cash from the U.S. Government and into the hands of the Taliban, and the change in rules of engagement handed down by McChrystal, also in 2009. Second, by including the civilians’ stories (Aaseya and Rahim) and drawing interesting parallels between their desires and the desires of their “enemies” (the Americans; Nathan, Tenley). Are these parallels realized? I feel the seeds are there, but the connections aren’t as alive on the page as they could be. When I finished writing Flashes of War I could say one thing very definitively: War is complicated; the line of blame can never be traced back to one, single point. I’m still exploring that truth in The Longest Day of the Year. Can I show the complexity of this truth on a human level that transcends war, gender, culture, and circumstance? Can I show it in a way that reveals our common humanity? That’s what I want to do.

Published on May 05, 2014 05:00

May 1, 2014

Revising the Novel: The Terrible Middles

The novel--both its storyline and its role in my life--has taken over my sleep. Sometimes, to positive effect; two nights ago I dreamt a scene with a Taliban soldier pulling a tooth out of his own mouth as a gesture of loyalty, demonstrating how much he would readily give to fight and live the way he does. I may not use the scene in my novel, but I certainly understand my character better now. Other times, this infiltration is to negative effect; that same night I dreamt I was trying to find a highly respected agent's house in NYC for a meeting. I had the wrong address, but eventually arrived, only to discover the door to his home opened into a mansion full of other writers vying for representation. A butler quickly shuffled me into a room of "would-be's." The agent was always within sight, only in an adjoining room where the "real" writers were. Pretty awful to wake up to that...and also pretty silly.

I know what all this means: I've hit the terrible middles. The rush and joy of writing the first third of the novel are over (well, revising the first third and increasing it by 42%, to be more precise). Right around page 100, the real digging in begins. This is where we have to make good on all we've set up and we have to do so without muddling or dragging along. For me, what that means is that I've got to write my scenes and narrative exposition even if I'm boring myself and won't use those words later. By pushing through, I'm teaching myself about my characters. I don't know any other way to do this. Call it paying dues, call it process, call it hazing--whatever it is, straight through is the only way I know.

This requires extra supplements of things like coffee and long conversations with the dog.

It also requires keeping faith in my project. I'm not getting any of those nice little sentences that pat me on the back as I go along. I'm getting a page of mud that only gets muddier. The consolation I have is that some message will be decipherable after a while (20 pages? 40? 80?). I'm crossing my fingers I'll come out cleaner on the other side.

One question I keep running into has to do with limited 3rd point of view narrators and the idea of interior monologue. To me, interior monologue is and only ever can be 1st person. But I've had several readers point out passages of what they call "interior monologue" that aren't working. What they mean, I think, is that the passages of limited 3rd POV are so close to Nathan's world, they may as well be interior monologue...and are therefore pretty damn useless. Once a novel starts going into its characters heads, forget it. It may sound trite, and indeed there are exceptions, but good god--someone's head? No thanks. Mine's complicated enough, thank you very much.

It takes skills I don't yet have and an imagination that can think outside the box in order to avoid this trap. I can talk about it in others' writing until the cow's come home, but ask me to solve it on the spot in my own work, right now? Uh...I'll get back to you. Right now, I'm falling. I've stepped into the trap and it's a long way down. But at least I'm aware that what I'm doing will eventually self-destruct. Meantime, I've returned to Jeff Vandermeer's inspiring Wonderbook for assistance. Rereading some of his advice yesterday, I was reminded of "interruptions" and "contamination." I'll leave readers with a bit of insight from him, as well as the above image from page 142-143 titled "Life is Not a Plot." Gosh, he's a gem of a helper. Here goes:

On what not to dramatize: "Beyond the eccentricities and skill set of the writer, the decision about what to dramatize concerns emphasis on how 'bringing it to life' will either support of destabilize your story. Action scenes with no emotional stakes involved are fairly pointless to commit to the page."On interruptions: "Interruption refers to, for example, the suicide note found sooner than intended or the unexpected phone call, or the stranger who starts screaming obscenities at your main character as he or she walks home...Since the real world often interrupts us, so, too, should it interrupt scenes...Look for opportunities to interrupt your own scenes, sometimes even pushing up events meant to occur later in the novel or story."On contamination: "Contamination can refer to the ways in which time wormholes through a scene, but also to some other presence beginning to infiltrate the edges of the scene, at first undetected by the reader because of the subtle nature of the progressions."On the role of time: "[A writer's] use of time is often a measure of the uniqueness of their personal view of the world."On narrative design: "One of the fundamental traits of design in fiction is that it requires the writer to know the difference between the daily existence of a character and a context in which some situation arises that requires the character to grapple with an issue or problem, whether internal or imposed by the world. In most cases, a normal day in the life of a spy, dragon hunter, or skydiver is not automatically a story, any more than is a normal day in the life of a toll booth operator......Never discount how your process affects how you view elements of narrative design."

I know what all this means: I've hit the terrible middles. The rush and joy of writing the first third of the novel are over (well, revising the first third and increasing it by 42%, to be more precise). Right around page 100, the real digging in begins. This is where we have to make good on all we've set up and we have to do so without muddling or dragging along. For me, what that means is that I've got to write my scenes and narrative exposition even if I'm boring myself and won't use those words later. By pushing through, I'm teaching myself about my characters. I don't know any other way to do this. Call it paying dues, call it process, call it hazing--whatever it is, straight through is the only way I know.

This requires extra supplements of things like coffee and long conversations with the dog.

It also requires keeping faith in my project. I'm not getting any of those nice little sentences that pat me on the back as I go along. I'm getting a page of mud that only gets muddier. The consolation I have is that some message will be decipherable after a while (20 pages? 40? 80?). I'm crossing my fingers I'll come out cleaner on the other side.

One question I keep running into has to do with limited 3rd point of view narrators and the idea of interior monologue. To me, interior monologue is and only ever can be 1st person. But I've had several readers point out passages of what they call "interior monologue" that aren't working. What they mean, I think, is that the passages of limited 3rd POV are so close to Nathan's world, they may as well be interior monologue...and are therefore pretty damn useless. Once a novel starts going into its characters heads, forget it. It may sound trite, and indeed there are exceptions, but good god--someone's head? No thanks. Mine's complicated enough, thank you very much.

It takes skills I don't yet have and an imagination that can think outside the box in order to avoid this trap. I can talk about it in others' writing until the cow's come home, but ask me to solve it on the spot in my own work, right now? Uh...I'll get back to you. Right now, I'm falling. I've stepped into the trap and it's a long way down. But at least I'm aware that what I'm doing will eventually self-destruct. Meantime, I've returned to Jeff Vandermeer's inspiring Wonderbook for assistance. Rereading some of his advice yesterday, I was reminded of "interruptions" and "contamination." I'll leave readers with a bit of insight from him, as well as the above image from page 142-143 titled "Life is Not a Plot." Gosh, he's a gem of a helper. Here goes:

On what not to dramatize: "Beyond the eccentricities and skill set of the writer, the decision about what to dramatize concerns emphasis on how 'bringing it to life' will either support of destabilize your story. Action scenes with no emotional stakes involved are fairly pointless to commit to the page."On interruptions: "Interruption refers to, for example, the suicide note found sooner than intended or the unexpected phone call, or the stranger who starts screaming obscenities at your main character as he or she walks home...Since the real world often interrupts us, so, too, should it interrupt scenes...Look for opportunities to interrupt your own scenes, sometimes even pushing up events meant to occur later in the novel or story."On contamination: "Contamination can refer to the ways in which time wormholes through a scene, but also to some other presence beginning to infiltrate the edges of the scene, at first undetected by the reader because of the subtle nature of the progressions."On the role of time: "[A writer's] use of time is often a measure of the uniqueness of their personal view of the world."On narrative design: "One of the fundamental traits of design in fiction is that it requires the writer to know the difference between the daily existence of a character and a context in which some situation arises that requires the character to grapple with an issue or problem, whether internal or imposed by the world. In most cases, a normal day in the life of a spy, dragon hunter, or skydiver is not automatically a story, any more than is a normal day in the life of a toll booth operator......Never discount how your process affects how you view elements of narrative design."

Published on May 01, 2014 05:00