Richard Denning's Blog, page 17

August 10, 2011

Battle of Maldon – August 10th 991

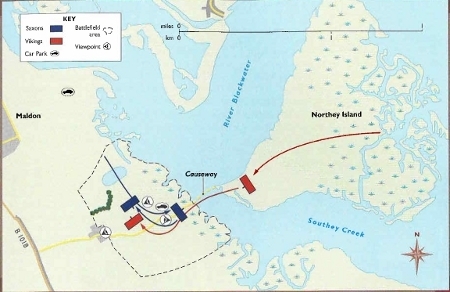

One of the more well known battles between the Saxons and Vikings was the Battle of Maldon. This is due in part to the existence of a poem from soon after the battle that tells us about who took part and what happened. It is also one of the few battles from the time where we are reasonably certain where it took place.

The Battle of Maldon was fought on the 10th of August in 991 near the small town of Maldon beside the River Blackwater in Essex. It took place during the reign of the weak king, Aethelred the Unready. What is interesting is that this battle and its aftermath show the two main approaches to dealing with the Vikings. Some leaders would fight them and if successful this approach would often force the Vikings to come to terms and make peace for a while. The other approach was to bribe them with money or land. This might work and save lives in the short term BUT it could mean the danes felt that since threats had worked before why not try again. The Saxon leader at the battle favoured resistance and we shall see what happened.

The battle occurred during the years of Viking raids and invasions that raged on during the 8th to 10th centuries. Maldon was a coastal town and so vulnerable to attack. It had been fortified but its wealth still made it a target for the Vikings who had moved on there after attacking Ipswich. These raids on the east coast were costly and it seems that the local Saxon lord was Earl Byrhtnoth determined to try and engage the Vkings in a pitched battle in an attempt to destroy the host.

The Battlefield

Earl Byrhtnoth having heard of the Viking raids called out the local Fyrd (the militia which would defend the local area ) and along with his huscarls (personal troops) his thegns (lords) led the English against the Viking invasion.

Initial deployment

It is thought that the armies had perhaps 2000 men each (really we don't know for certain).

The Vikings had chosen not to directly assault Maldon (which would mean attacking the fortified port) but had landed in the safe anchorages and various channels of the estuary and then assembling on Northey Island had move towards the causeway which connected it to the main land via a causeway. The Saxons moved to the end of the causeway At the start of the battle the causeway was flooded and so what occured was a stand off with the two armies hurling abuses and challenges.

The Battle starts

Initially a few Saxon warriors held the causeway and denied the Vikings passage but then Byrhtnoth ordered the army to pull back and permit the enemy to cross. This is unlikely to have been good sportsmanship or a sense of honour. Byrhtnoth wanted to destroy the Vikings and so, possibly fearful they would just get in their ships and leave, he allowed them onto the main lands.

The battle then proceeded in a fairly standard manner with an exchange of arrows, slingstones and javelins. Then the main bodies closed and the push and shove of the shield wall ensued. It may be that the Saxons were doing OK until something unexpected happened. Byrhtnoth seems to have believed that an enemy leader was challenging him and stepped forward to engage in one to one combat. The Vikings fell upon him and cut him to pieces.

Once the leader was dead the Saxon Fyrd turned and fled. Byrhtnoth's household troops and retainers fought over the body of their lord until slain but after his death the battle was over in moments.

The Aftermath.

The battle having ended in an Anglo-Saxon defeat, the Vikings went on to pillage Maldon. After the battle the Archbishop of Canterbury advised King Aethelred to follow the other policy and to try and buy off the Vikings rather than fight them. The King agreed and as a result a payment of 10,000 pounds of silver was handed over as Danegeld. The idea was that the Vikings would not come back but year after year return they did. Ultimately, despite English resistance, a Viking king would sit on the throne – Canute and the Vikings would rule England for 25 years.

A statue of Byrhtnoth in Maldon

The Poem

Fragments of an account of the battle probably written soon afterwards still survive today. The poem is embellished by proud boasts and accounts of the bravelry of the Saxons in much the same way that the poem Y Goddodin tells of the attributes and abilities of the defeated British at the earlier battle of Catreath in c597. So what we have is a piece of propaganda. Yet it does give us something of an outline of the battle as well as include references to some snapshots of the action that help us understand the weapons used.

My own historical fiction, The Amber Treasure, is set during the late 6th century and includes an account of the battle of Catreath.

Mad Zealot on a holy mission

Character sketch from The Last Seal. Sketch is by Gill Pearce of Hellion's Art

Summary: Disturbed almost insane religious Leader of the Liberati, whose goal is releasing the "instrument of judgement" Dantalion to judge the unworthy.

More Info: Ex roundhead soldier, fought for parliament through a deep belief he was serving the good and godly cause. Faith shattered when his father and brother were executed by Cromwell for opposing his dictatorship and felt betrayed by the commonwealth. Became mentally unstable and came to believe nothing mattered and that all humanity were sinners ready for judgement. Learns of the existence of Dantalion who he believes is an angel and is the instrument of divine judgement. Charismatic speaker, who is able to persuade other of similar mind to join his holy cause. Helps to starts the Great Fire if London in an attempt to destroy the mystical seals that bind Dantalion but then starts to doubt he is working for God.

What happens in the end? To find out read The Last Seal.

Check out the book's Facebook page here:http://www.facebook.com/TheLastSeal

Read part of the book here: http://www.richarddenning.co.uk/thelastseal.html

August 7, 2011

What's for dinner? Food in the 17th Century

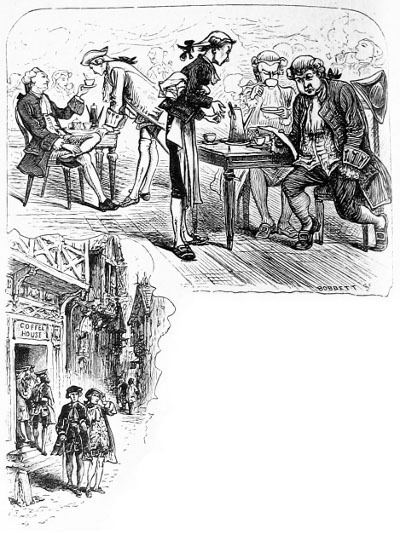

Above: Samuel Pepys gives us many insights into what folk ate and drank in the 1660′s.

If you were living in London around the time of the Great Fire on 1666 WHAT would you be eating and drinking? Today in the blog I look at this subject.

Firstly the city of London – and elsewhere – would contain a number of Chop Houses. Chop houses were places where city folk, traders and businessmen discussed their commercial affairs over plates of traditionally cooked meats such as steaks and chops, which were usually grilled. These were consumed with beers or fine wines.

The 17th century is when the forks began to be used in Britain. They were introduced from Italy and were seen as unmanly at the start but gradually became accepted over the next century.

This was also the century when many new foods were introduced into England. By and large these were only for the wealthy. These new foods included fruits from exotic locations in the new world such as bananas and pineapples.

This period also saw the introduction of chocolate (as a drink) coffee and tea. In particular it was the arrival of coffee that brought with it a new phenomenon – the coffee house. The first coffee house in Britain was opened in 1652 in Oxford and the first in London the same year in Cornhill. They spread rapidly and by the end of the century over 3000 would exist around the country. By the time of the fire there were many in London. They became places just like today to meet friends, exchange news and gossip – to the extent that Charles II actually tried, and failed, to close them as they were seen as hotbeds of sedition and criticism.

For the majority of the population food was basic and boring like bread, cheese and onions. Pottage was an almost daily part of the diet. This was a stew that was prepared by boiling grain in water to make a kind of porridge. If you could obtain it you might add some meat or vegetables.

For the better off pies, pastries and puddings were popular – in many cases richer than what we would eat today. Due to the fact that Prince Charles I had a French wife more elaborate dishes with strong sauces were introduced and were called kickshaws, after 'quelquechose', the French word for 'something'. Charles II married a Portuguese princess and so the fashion for European food remained strong in his reign. So we see the use of anchovies, capers and wine, roux, ragouts and fricassés. Salads using raw uncooked vegetables started to be eaten as well in this time.

It is interesting that when Samuel Pepys saw the fire approaching in 1666 the items he choise to bury and save was a large parmesan cheese and his wine – showing what he valued.

A Samuel Pepys Feast

Taken from a superb source on food at this time "Pepys at Table" here we have a typical festive feast:

Soup from Ox tongue spiced with nutmeg

Sliced leg of lamb with artichoke heart, kidneys and topped with rasperies and redcurrant.

Herring pie

Scambeled eggs, anchovies and nuts

Stewed prawns.

Minced Pies (with meat in as well as fruit and spices).

Chesecake or Syllabub to finish.

Washed down with spiced wine.

So some foods are familiar today. Many have changed and in particular combinations of foods and spices are maybe a bit outlandish to today's palate. Indeed often folk ate food at breakfast (such at lamb chops and kidneys) less common in this modern age. Nevertheless it is obvious that the better off ate and drank well as can be seen in this entry by Samuel Pepys in 1661:

"I went with Capt. Morrice at his desire into the King's Privy Kitchin to Mr Sayres the Master-Cooke, and there we had a good slice of beef or two to our breakfast. And from thence he took us into the wine-cellar; where by my troth we were very merry, and I drank too much wine."

This is a series of articles written to celebrate the release of the new paperback of The Last Seal – a historical fantasy set during the Great Fire of 1666.

Check out the book's Facebook page here:http://www.facebook.com/TheLastSeal

Read part of the book here: http://www.richarddenning.co.uk/thelastseal.html

August 5, 2011

A Decade a week: 1640 to 1649

A world turned upside down!

The 1640s are the decade when England would be torn apart by a Civil War which would kill a higher % of its population than even the first and the second world war. A king would fall and by the end of the decade the nation was a republic. It was a world turned upside down as a popular ballad of the day put it.

At the start of the decade the strongest and closest of Charles' supporters were William Laud - Arch Bishop of Canterbury – and Thomas Wentworth (shown above) – appointed Earl of Strafford by Charles. Both were advocates of the Divine Right of Kings and of absolute rule. These concepts were now an anathema to the Paliamentarian forces that were growing and to whom Charles was now forced to turn for funds.

The Second Bishop's War and the Short Parliament

There had been no lasting peace and settlement between Charles and the Presbyterian Scots – the Covenanters who opposed Charles efforts to enforce English style churches and bishops on them. Both sides started to raise troops again and with the Scots poised to invade England, Charles desperately needed funds to build an army.

Charles called up both English and Irish parliaments in early 1640. Under the control of Wentworth, the newly created Earl of Strafford, the Irish Parliament voted Charles a payment of £180,000 and undertook to raise an army of 9,000. The response of the English Parliament was far different. Anti-Royalist Parliamentary candidates were voted into the commons in large numbers and undertook a stubborn attitude. Strafford tried to negotiate a compromise whereby the king would give up the unpopular Ship Money tax in exchange for £650,000 . Parliament would not agree to a payment without radical reforms – which Charles and Strafford were totally unwilling to discuss. Charles dismissed the "Short Parliament" in May 1640 after just a month.

Meanwhile the Scot's Covenanter army had captured Durham and Newcastle and was strongly poised to dominate all of Northern England. Without the funding to raise a substantial army, Charles turned to Stafford who at least had raised funds and troops and sent him north to confront the Scots. Unfortunately Stafford became ill with dysentery and with the English army, outnumbers and poorly equipped, Charles was forced to make peace. In the Treaty of Ripon, the Scots were paid £850 a day and continued to occupy northern England UNTIL a final peace was found.

With no choice, in November 1640, Charles summoned what was later to become known as the Long Parliament. Of the 490 or so members, 390 of them were opposed to him and only 90 or so were Royalist. This was not going to be easy.

The Long Parliament and the end for Strafford

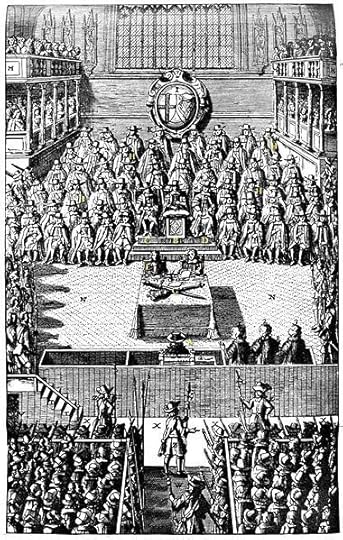

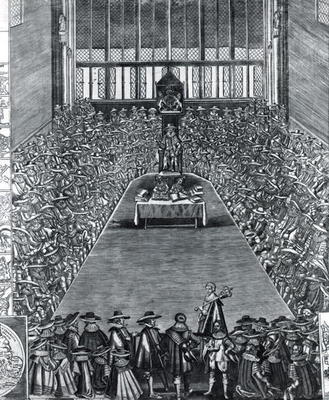

Charles I storms parliament 1642

Once assembled and in uncompromising mood, the Long Parliament immediately impeached Arch Bishop Laud for High Treason.

Next, Parliament under the leadership of John Pym (one of the members who Charles had arrested in 1628) went after the other of Charles' supporters: Strafford. Accused of abusing his power in Ireland and involving Irish troops in English affairs, he was put on trial for High Treason and, although that case collapsed, in April Parliament forced through the bill of attainder which demanded Stafford be executed. Charles tried to save Stafford but with no support in Parliament he was obliged to allow the execution.

Parliament now embarked on a number of steps to reform government. In February 1641, fearful that the King would try and dissolve parliament it passed the Triennial Act which required that Parliament was to be summoned at least once every three years, and if King failed to do so, the members could assemble on their own. Later Charles had to agree to not dissolving parliament without its own consent. Further steps were taken - Ship money, fines in destraint of knighthood and forced loans were declared unlawful, monopolies were cut back severely. The Court of the Star Chamber which had been prosecuting religious dissenters was abolished and taxation put on a legal footing.

The mainly protestant and puritan parliament now turned to religion. Laws were passed attacking and undermining bishops – although these blocked in the House of Lords.

So far all this had been one sided. However through these months, Charles had managed to gain some concessions that improved his financial situation, helped him strengthen the army AND he managed to make peace with the Scotish Covenant by guaranteeing Presbyterianism.

Parliament moved forward with even more changes – finally reaching the line which Charles would not cross with the Grand Remonstrance in November 1641. This was a long list of grievances against the King, the Catholic Queen, Henrietta Maria and the Kings advisor's. It painted a picture of a grand catholic conspiracy. It gave voice to the Parlaimentarian's beliefs of the King being under the influence of a great Papist plot. The Commons passed the act but the Lord's and the King Rejected it.

Charles, outraged by the attacks of Parliament took an armed party to the Commons to try and arrest Pym and other prominent members. Never before had a King gone to the Commons and tried to do this. The members managed to escape and the door to the chamber was shut in his face (still ceremonially done today when the Queen sends for the Commons to join her for the State opening of Parliament.) This failure was a political disaster as it pushed more members into the Parliamentarain camp.

The Irish Rebellion

In 1641 the Irish Gaelic, Catholic majority had risen rose up in rebellion against the English rule that Stratford had imposed. There was a massacre of protestants and the ensuing outrage in England ensured that Charles would have to act. However when in early 1642 he asked parliament for funds Parliament passed the Milita Act.

This act attempted to wrench control of the army from the king. This was a direct attack on the royal Prerogative. Kings controlled armies and waged wars. The House of Lords refused to pass the act. The King refused to give consent. Pym forced through the act via the Commons alone – a breach of the rules and laws of the land which requited assent of Commons, Lords and Monarch.

It's War!

After the failure to arrest Pym and the other leaders of Parliament, Charles had left London in January 1642. The Ordnance Act of March was the final straw that convinced him that military action to suppress parliament was needed. In the summer of 1642 both the King and Parliament began raising troops. The Earl of Essex took command of Parliament's troops. On the 22nd of August 1642, Charles raised his standard at Nottingham and called for an army to join him. He set up his capital at Oxford and began making plans. With the Royalist army assembling in the Midlands, Essex took the Parliamentarian army that way.

The first conflicts of the English Civil war was about to begin.

The 1642 Campaign

The King, beginning with around 2000 men, raised more troops in the Midlands as he moved south west towards Shrewsbury. Shortly after the King had raised his standard at Nottingham, Essex led his army north into the Midlands and across into the Cotswolds. By September both Essex and the King had around 20,000 men and were in close proximity on either side of Worcester. A clash was inevitable. That first battle was at Powick Bridge on 23rd September when Price Rupert – the King's nephew and cavalry commander – defeated a Parliamentarian cavalry force and showed that in the early war the Royalist had an edge in terms of cavalry forces.

After that first battle, the King decided to strike towards London and try and reach it before Essex could get back there. Essex responed my marching towards London as well. So it was that Essex finally brought his field army into the path of the Royalist army at the little village of Edgehill. There on 23 October 1642, the first major battle of the war was fought. Both the Royalists and Parliamentarians claimed it as a victory but in truth it was inconclusive. The armies moved apart again and there was a chance for Charles to reach London but he hesitated and by the time he did move that way Essex had again got in the way and at the battle of Turnham Green was able to prevent the King breaking though.

The year ended with Charles forced to withdraw to Oxford which would serve as his base for the remainder of the war.

1643

The war went well for the King in the early part of 1643. Firstly the Royalist forces won at Adwalton Moor gaining control of most of Yorkshire. Likewise there were victories in the west of England at Lansdowne and at Roundway Down which enabled Prince Rupert to take Bristol.

The turning point came in the autumn of 1643, Essex's army broke the siege of Gloucester and then defeated the Royalist army at the First Battle of Newbury (20 September 1643) and then returned triumphantly to London. Other Parliamentarian forces won control of Lincoln.

Late in the year both sides turned to political manoeuvering to gain an advantage in numbers. Charles decided to negotiate a ceasefire in Ireland, freeing up English troops to return to England, while Parliament offered concessions to the Covenanter Scots in return for aid and assistance.

1644

With the new help of the Scots, Parliament won at Marston Moor (2 July 1644), gaining York and control of the north of England. This battle showed Oliver Cromwell's potential as both a political and a military leader. Elsewhere the war went better for the King. The Battle of Lostwithiel in Cornwall, kept the King's cause alive in the south-west of England whilst the inconclusive fight at Newbury (27 October 1644), was also encouraging for the Royalists.

1645

In 1645 Parliament decided to take decisive action to end the wat and passed the Self-denying Ordinance. All members of either House of Parliament agreed to lay down their commands. The Parliamentarian army was totally reorganised into the New Model Army under the command of Sir Thomas Fairfax and with the impressive Cromwell as his second-in-command.

This New Model Army showed its tactical superiority over the Royalists at the Battle of Naseby on 14 June and the Battle of Langport on 10 July. In these two battles Charles' armies were annihilated.

Oliver Crowell

The King attempted to consolidate a power base in the Midlands and although he was able to fortify Oxford, Leicester and Newark on Trent, with the loss of his field army and with his resources exhausted he was clearly losing the war .

1646-47

With the New Model Army closing in on him and with Oxford under siege, Charles decided to surrender to the Presbyterian Scottish army at Southwell in Nottinghamshire in May 1646. He had hoped he might be able to negotiate a peace with them but the Scots eventually handed him over to the English Parliament. With the King imprisoned, the First English Civil War was over.

Parliament did not really at first know what to do with Charles. There followed months of negotiations. In November 1647, Charles escaped from Hampton Court and fled to the Isle of Wight but found that the governor was sympahetic to Parliament and imprisoned him in Carisbrooke Castle. From Carisbrooke, Charles was however able to try to bargain with the various parties and on 26 Dec. 1647 he signed a secret treaty with the Scots under which in exchange for concession on religion they agreed to restore him to the throne. He sent out messages to his supporters and prepared an uprising to coincide with the Scottish invasion. Charles was betting everything on one last roll of the die.

1648 – The Second English Civil War

The King's English supporters rose in rebellion in July 1648 and as agreed with Charles, the Scots invaded England. However Charles dice roll was a bad one for the uprisings were quickly suppressed and at the Battle of Preston the Scots were crushed by the New Model Army. The king had lost the chance to win his throne back and had turned Parliament even more against him.

The Trial of A King

At the end of the First English Civil War many in Parliament were willing for Charles to remain king under a revised constitution. However by starting the Second War and in particular involving the Scots he lost much support in Parliament.. Nevertheless there was still reluctance to order a trial. A King of England had never been put on trial before. Kings had been murdered and deposed but not put on Trial. There was no real constitional basis for such a trial.

The Parliamentarian Army under Cromwell felt very different. The Army marched on Parliament and evicted all but 75 Members from Parliament – the so called Rump Parliament. The Rump was ordered to set up the trial of Charles I for treason. The Trial involved much argument and Charles totally refused to accept its validity. To the end he maintained that he was answerable only to God. Found guilty of High Treason, his beheading took place on a scaffold in front of the Banqueting House of the Palace of Whitehall on 30 January 1649.

The Rump Parliament now ruled England BUT in effect was a puppet of the Army which was under the control of Cromwell. The 40′s drew to a close with Cromwell taking the Army to Ireland to suppress a Royalist/Catholic uprising without mercy. Like the slaughter of Protestants early in the Irish uprising against the rule of Thomas Wentworth this would colour how many Irish Catholics and Protestants felt about each other for generations – right down to the present day.

Next Week: No Christmas for you!! The Years of the Commonwealth.

Coming next week: 1650 to 1659

This article is one of a series connected with the release in August of the new paperback of The Last Seal my historical fantasy set during the Great Fire of 1666.

August 3, 2011

Cavalier who lost power in the commonwealth aims to regain influence by freeing a demon

Character sketch from The Last Seal. Sketch is by Gill Pearce of Hellion's Art

Artemas

Summary: Flamboyant Cavalier and leader of the Liberati.

More info: Fought for the king in the civil war but lost power and influence during the Commonwealth. He then inherited from his father the secret of how to serve the demon Dantalion as well as the leadership of the Liberati. Cynically using and manipulating the preacher Matthias. Plans to release the demon and through him gain power. He will do anything to satisfy his goals even see London burn.

To find out read The Last Seal.

Check out the book's Facebook page here:http://www.facebook.com/TheLastSeal

Read part of the book here: http://www.richarddenning.co.uk/thelastseal.html

July 31, 2011

The battle between two secret societies sets London Ablaze

The Liberati are a secret society which in ancient times served the demons who ruled this earth and through them exerted power over mankind. Though defeated in the wars in which mankind liberated themselves, through the ages they have strived to free the demons and through them rule our world. In The Last Seal, the Liberati aim to free the Demon Dantalion and unleash terror on London in the 17th Century. They are lead by the Cavalier Artemis

The Praesidium order were the original instigators of mankind's triumph over the demons. Throughout history they have acted to keep the demons away from our world and have opposed the Liberati's attempts at each stage. Three Hundred years ago the Liberati warlock Steven Blake freed the demon Dantalion but ther Praesidium were there to stop them. Their leader Cornelius Silver Imprisoned Dantalion beneath London.

Now, in the year 1666, the Liberati are back and aim to free the demon. A year ago the Praesidium were all but destroyed. Can the surviving member, Gabriel, manage to defeat their plans?

What happens in the end? To find out read The Last Seal.

Check out the book's Facebook page here:http://www.facebook.com/TheLastSeal

Read part of the book here: http://www.richarddenning.co.uk/thelastseal.html

July 29, 2011

A decade a week: 1630 to 1639

The King Ruling Alone

Charles had dismissed Parliament in 1629. Deprived of access to legitmate grants of money to fund wars, Charles was obliged to make peace with Spain and France and as a result England sat out most of the rest of the Thirty Years War.

The nation's finances were, however, a mess and Charles was then faced with a desperate need to raise revenue without reconvening Parliament. To do this he started to impose a variety of taxations that he believed he could get away with or were perhaps in theory legitimate rights of the king.

Distraint of Knighthood

This was a law from 1279. It stated that anyone (knights) who earned £40 or more each year had to be present at the King's coronation. This law had fallen in to disuse but Charles fined all individuals who had failed to attend his coronation in 1626.

Ship Money

This Tax was in theory levied on coastal towns during times of war to pay for building of ships. Charles enforced it throughout the land and during peace time. Each year between 1634 and 1638 this tax brought in around £200,000. This was a deeply unpopular tax and there where legal challenges such as by John Hampden in 1637. However, the courts declared that the tax was within the King's prerogative.

Monopolies

Like Elizabeth and James before him Charles sold trade monopolies – bringing in something like £100,000 a year. This was directly in violation of the Monopolies Act of 1624 which James had assented to.

Act of Revocation

Charles particularly irritated the Scottish nobility by declaring that all existing rights and titles were revoked and only maintained IF the King was paid an annual fee.

There were other taxes and obscure laws as well. Charles was in theory within his rights with all the taxes and laws as he was careful to stay within areas that could be considered Royal Prerogative but it was clear that he has put many noses out of joint and that if ever Parliament was recalled he would be in for a bumpy ride.

Ireland

England was still governing Ireland via Lord Deputy appointed by the King. Throughout most of the 1630s this was Thomas Wentworth, future Earl of Stafford. Wentworth had originally been critical of the King but after the King signed the petition of Rights switched sides to strongly support the king. When he did this is was widely accused of having abandoned much of his previous ethics. He would become a strong supporter of the Divine Right of Kings along with Archbishop Laud (see below).

Wentworth's attitude to Ireland was expressed thus: "I see plainly that, so long as this kingdom continues popish they are not a people for the Crown of England to be confident of."

Once in post Wentworth pursued an autocratic approach and in effect did his best to suppress Irish aspirations and to impose upon them how he believed the nation should evolve – as a mirror of England. To these ends, and to help raise funds for Charles, Wentworth confiscated the lands of Catholic nobles, opposed steps to grant equality to Catholics and enforced strict economic models that whilst actually helped improved the economy in Ireland were not popular.

Overall the result of Wentworth's government would be an uprising in Ireland.

Religion, Puritans and William Laud

In 1633 Charles appointed as Archbishop, William Laud. Laud believed strongly in the use of sacraments and icons in churches and in the authority of bishops and church hierarchy. This ran in opposition to a strong puritan/calvanist belief amongst many in the country which stressed individual salvation and whose members opposed the authority of bishops and disliked icons – all of which they saw as papist, catholic influences.

Laud insisted that all services were conducted using the form laid out in the Book of Common Prayer. With Charles' agreement Laud began using the court of the Star Chamber to put on trial religious dissenters. It had the right to impose severe punishments and even subject the victims to torture. It was a crack down which lead to a fresh wave of emigration to America.

The First Bishop's War

In Scotland, Charles took on the Presbyterian church whose members worshipped in independent churches answerable to their own elders and affiliated together but having no Bishops. Charles tried to force upon them a book which was in effect the book of Common prayer as well as trying to bring in bishops. The Presbyterian Scots reacted very negatively and in 1637 there was an uprising sparked off by the first use of the book in church. This revolt took shape under the leadership of the National Covenant – the representatives of the individual churches and this anti Catholic, pro Presbyterian movement – called the Covenanters – were soon the defacto government in Scotland and would play a large role in the Civil War of the next decade. In 1638 the General Assembly of Churches in Scotland abolished Bishops. This was too much for Charles.

Charles had to try and supress this uprising and in 1639, without calling Parliament, managed to raise a military force and send it north. However, although it was able to recapture Berwick upon Tweed, Charles realised it was not strong enough to actually defeat the Covenanters. The best he could achieve was an agreement where the Covenanter's government was temporaily dissolved and the Scottish Parliament and Council of Churches called. Charles knew however that the Scots were not likely to alter their stance and so The First Bishop's war ended with an uneasy truce which both sides knew would not last.

Parliament Recalled.

If he was to get anywhere with suppressing the Covenanters, Charles needed funds to raise an army big enough for the purpose. He had used up all his options for legal methods of raising cash – and in fact had stretched the law a bit too much. Many members of the commons were puritan and many were affected by his tax raising steps of the Personal Rule. Thus Charles knew that Parliament would be stubborn BUT he had no choice. As the 1640s began and with unrest and dissatisfaction at a high level, Charles was obliged to summon Parliament.

Coming Next Week: Its War!

Meanwhile In Europe

Whilst Britain was self absorbed by its own problems the Thirty Years War raged on. The Swedes, lead by Gustavus Adolphus and probably concerned that their main trading partners – the Protestant German states – were under pressure from the Holy Roman Emperor, joined and championed the Protestant cause and won a series of battles, pushing the Imperialists back until he was finally killed in 1632 at the Battle of Lutzen.

In 1635 the Peace of Prague brought to an end conflict between the Protestant Germans and the Empire. The northern states were granted religious independence but agreed to the overlord-ship of the Emperor.

Sweden did not accept the Peace of Prague and fought on. France, a catholic country, decided to back the Swedes mainly in an attempt to cut down on the power of the Spanish Hapsburgs which of course included the Holy Roman Emperor who had gained from the Peace of Prague.

So the war continued at the end of the decade.

Other events:

1630: Native Americans introduce popcorn to the English settlements.

1631: Algerian Pirates attack Cork, Ireland.

1635: The Japanese Emperor closes Japan's borders. Europeans landing would be beheaded.

1637: Tulipmania in Holland. Prices of Tulips sore to vast levels. Eventually like the DOTCOM episode the bubble bursts.

Coming next week: 1640 to 1649

This article is one of a series connected with the release in August of the new paperback of The Last Seal my historical fantasy set during the Great Fire of 1666.

July 27, 2011

Physician determined to gain revenge on his father's killer

Character sketch from The Last Seal. Sketch is by Gill Pearce of Hellion's Art

Summary: A doctor and the cynical son of a Praesidum member who was murdered by Artemis and seeks revenge.

More Info: His father was a member of the secret society The Praesidum who tried to recruit Tobias to his organisation so that he would take over his role after his death but Tobias ridiculed and rejected him. Tobias does not believe in the demon, Dantalion – and resists Gabriel's attempts to persuade him to help. When his father died in battle against the Liberati, Tobias blames Gabriel – but wishes revenge on the Liberati member who killed his father.

Does he get his revenge? Read The Last Seal to find out.

Check out the book's Facebook page here:http://www.facebook.com/TheLastSeal

Read part of the book here: http://www.richarddenning.co.uk/thelastseal.html

July 24, 2011

Superstition and Omen in 1666

The 17th century is the age of Newton and Harvey and other scientists that discovered many of the scientific truths we know today. YET it was still a time where people believed in magic, witchcraft and omens. It could be a paranoid time. Today I look at some of those beliefs.

Witchcraft and Magic

Put simply in this time period, despite the growth of science people believed in Magic and in witchcraft. It was during the reign of Elizabeth I that campaigns to catch and try witches began – around 1563 and these were developed during the reign of James I. The estimate of the number of persons hanged as witches in England in the century or so of active trials was about 1,000. The first person hanged for witchcraft was Agnes Waterhouse at Chelmsford in 1566, the last was Alice Molland at Exeter in 1684.

If you were a women who was old, ugly, had warts you were at possible risk of accusation. If you fell out with a neighbour they might just call you a witch. Then the search would begin for "evidence" such a calf being still born in the area or milk turning sour.

Prince Rupert's demon poodle

As an example of how much credence people might sometimes give to tales of magic and demons, in the civil war the Parliamentarians spread a rumour that Boy – Prince Rupert's dog (prince Rupert was nephew to King Charles I) – was a demon in disguise. Pamphlets circulated claiming that he had the power to predict the future, find treasure, alter his shape and was invulnerable to bullets. Alas if he did have this power, it failed him at the battle of Marston Moor in 1644, because Boy died at that battle.

Omens

The mid 17th century was a time of great superstition and people attributed significance to omens that they saw about them. There were Solar eclipses in the southern hemisphere in 1666. Comets had been seen in the skies in 1664. There was also lunar eclipses. People it seemed were willing to believe that any apparently natural occurrence had deeper meaning. For example it was widely reported that a hen's egg had been laid in Poland with the mark of the cross on it.

All of these – and many other occurrences were widely reported and believed by many to imply that some great catastrophe was looming.

Astrology

There was even a prediction made by William Lilly, the best known astrologer of his day who predicted the plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London (1666) in 1652. Of course the year 1666 would be likely to attract such predictions due to its signifiacnce (see below) and there were many predictions that DID NOT come true that are not reported but many people suggested after the fire that his (and other) predictions were to blame.

The End of the World

'And that no man might buy or sell, save he that had the mark, or the name of the beast, or the number of his name. Here is wisdom. Let him that hath understanding count the number of the beast: for it is the number of a man; and his number is Six hundred threescore and six.' Revelations 13:17–18

Every few years people predict that the world will end. Many people believed that 1666 was the end of the world!! In the Book of Revelations there is this passage that says that the number of the beast – of the devil is 666. In 1666 many people thought they were living in the year the world would end (because of that 666 bit.)

So then this is the world at the time of the Great Fire.

This article is one of a series connected with the release in August of the new paperback of The Last Seal my historical fantasy set during the Great Fire of 1666.

Check out the book's Facebook page here:http://www.facebook.com/TheLastSeal

Read part of the book here: http://www.richarddenning.co.uk/thelastseal.html

July 22, 2011

A decade a week: 1620 to 1629

Royal Prerogative vs Parliamentary Freedoms

The Stuart period is the time when parliament increasingly flexed its muscles. The parliamentary structure of King, Lords and Commoners came into being in Tudor times. At this time the King still ruled the country and directed foreign policy. Tudor parliaments would at times petition and try and persuade the monarch of a particular direction of policy BUT they were rarely critical and given the character of Henry VIII, Mary and Elizabeth one can well understand a reluctance to take on them on!

Monarchs needed to go to parliament primarily to get money. The monarchy had income from three sources:

1. Large crown estates owned directly by the monarch.

2. Feudal dues from the bulk of the nobility.

3. Import duties (Called Tonnage and Poundage).

All of THAT income was the king's by right. However at times of war and emergencies monarchs would go to Parliament who would then legislate ADDITIONAL taxation to raise funds that the the monarch needed. Parliament increasingly started to add restrictions and requirements linked to these grants.

James and Charles in particular objected to these restrictions – seeing them as an attack on their right as the God chosen King to rule. In particular they objected to any attack on Royal prerogative – areas they jealously guarded as the rights of the monarch:

The Right to go to war. (Technically still the Queen has to consent to going to war)

The right to choose alliances usually sealed by dynastic marriages.

The right to tax imports.

The struggle between Parliament and Monarch over these areas would be a feature of the next decade.

The Thirty Years war of 1618 to 1648 affects English Policies

In 1620 James was now 57 and was giving thought to the stability of the succession to his son Charles (later Charles I). Part of this would be the matter of the marriage of Charles – always a crucial part of alliances and politics.

James, his chief advisor, Villers (Lord Buckingham) and Prince Charles were all keen on a "Spanish Match" with the Spanish Infanta. This policy was put under threat by the Thirty Years war between (by and large) the Protestant nations of northern Europe and the Catholic nations of the south which included Spain.

James own son-in-law was a Protestant. This was Frederick V the Elector Palatine. In 1620 his opponent the Catholic Emperor Ferdinand II invaded Bohemia again and Spanish troops attacked Frederick's lands in the Rhineland .

James decided he had to help his son in law and called a Parliament in 1621 to fund the war. The Commons did not grant sufficient money to carry out this war but at the same time demanded that James attack Spain. They also insisted that Prince Charles should marry a Protestant. Furious at this attack on his Royal rights, James tore up the petition and dismissed Parliament.

Charles and Buckingham Take matters into their own hands

IN 1623, frustrated by the obstruction by parliament and determined to carry through their policies, Prince Charles and Buckingham travelled to Spain in secret in an attempt to reach an agreement on the Spanish match. This attempt was an utter failure. The Infanta hated Charles at first sight. Furthermore the Spanish court insisted that Charles convert to Catholicism and imposed other intolerable criteria. When Charles and Buckingham finally returned home they tore up the agreement which finally went down well with the people.

A change of heart

In fact once home Charles and Buckingham completely changed tack. They started to pursue and alliance and marriage with France and urged James to go to war with Hapsburg Spain. IN 1624, Charles persuaded James to summon parliament and now all apart from James were in concord. Parliament was happy to take an anticatholic stance and seemed happy to finance the war and although James refused to declare war, Charles and Buckingham - now increasingly the power in the country believed they had secured support for their stance. This would have significant influence on the direction of Charles' reign.

The end for James

Buckingham continued to exercise influence over Charles as James came to the end of his life. James grew ill in 1625 and died in March of that year. The funeral was magnificent and the public poured out an expression of sentiment and goodwill that showed that James had always managed to remain popular. After all he had managed to maintain peace throughout his 22 year reign.

Charles I becomes King

With the death of James, Charles inherited the throne. His first action – even before he was crowned was to conclude the French match that he had been negotiating since the failure of the Spanish venture. In haste and before Parliament could do anything to prevent it, he arranged a marriage in proxy to the French princess Henrietta Maria. Although Charles told parliament that he would not relax the anti-catholic laws he actually promised just that to the French King and even agreed to help the French suppress their own protestant minority, the Huguenots.

Charles gave further indication that that he was favouring a pro Catholic line by appointing as his personal chaplain a priest, Montagu, who was out spoke in his condemnation of many protestant beliefs. This perception in a protestant country that the King favoured catholism would strain relations with parliament and one day lead to many men backing parliament in a war against the king. But that is a tale for the next of these blogs.

Early Reign – Foreign policy and the Thirty Years War

Charles wished to aid his brother-in-law Elector Frederick V. The Hapsburgs were supporting the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II in the war against Frederick. The war was expanding and drawing in more and more nations. Charles wished to declare war on Spain and had decided to intervene directly in the war in Europe by sending troops. He went to parliament to ask for the funds to do this. Parliament did not want to send an army to Europe but prefered raids on Spanish treasure fleets and her colonies. To try and force the king's hand they authorised only a small amount of money and furthermore restricted Charles right as king to levy taxes on imports (The so called Tonnage and Poundage duties).

Although the House of Commons passed a bill with these terms, Charles advisor, Buckingham in the House of Lords had it thrown out. Charles and Buckingham ignored the wishes of parliament and started up the war with Spain. The war went badly and by 1626 parliament were baying for blood and demanding Buckingham's dismissal. Charles refused to comply.

Needing to fund the war which was draining funds badly, Charles started imprisoning anyone who refused to pay what he saw as his rightful duties. This caused outrage and in 1627 five knights who were so treated challenged the king's actions in court. The court decided that it had no right to interfere with the traditional rights of the King to levy taxes. However in 1628 parliament forced through the petition of rights which specified that the King could not levy taxes without Parliament's consent, impose martial law or imprison civilians without a fair trial. Charles agreed to this petition although in practice he did continue to levy taxes.

Decline of Buckingham's influence and his death – Failure in expeditions to aid the Huguenots

Although Charles had agreed in his marriage treaty to help France suppress the Huguenots but he did not go through with this. Indeed between 1627 and 1629, alarmed by the growth of the French navy, Charles decided to go to war with France and help the protestant's in France. Buckingham undertook naval actions designed to aid them including sending an expedition to seize Saint Martin-de-Re – a French strong hold near the Huguenot's base. These expeditions were a total disaster.

As a result of these failings, his poor handling of the Spanish match in the early 20′s and the failure of the conduct of the Thirty Years war at large, Buckingham was hounded and pursued by parliament.

In August 1628, Buckingham was assassinated. The public rejoiced at the news. For Charles, devoid of funds to pursue them, Villers' death also brought to an end the war with Spain and France. It did not however bring to an end the conflict between King and parliament.

In January 1629 Charles opened Parliament with a speech on the tonnage and poundage issue. The Commons responded by saying he had broken the Petition of Rights by imprisoning one of their members, Rolle, for refusing to pay. Charles ordered the adjournment of Parliament. Determined to have their say, the members of the House of Commons actually held the Speaker in his seat until they had passed resolutions on rights and the tax issue.

Furious, Charles had eight members of the House including a significant figure for the future, John Pym, arrested and then dissolved parliament. These men were seen as Martyrs by the public.

Having failed to raise funds for war, Charles made peace with Spain and France and then set about ruling alone and without Parliament for 11 years. This period is known as the Personal Rule or the Eleven Years' Tyranny.

Ruling without Parliament was quite acceptable in previous centuries but by the mid 17th century opinions were changing and perceptions of liberties and freedoms were growing. Charles still believed that he was answerable ONLY to God. Parliament and a good number of the people were beginning to feel differently. One day enough people would feel strongly enough about this to challenge the King. But not yet.

Next week – the Personal Rule.

Coming next week: 1630 to 1639

This article is one of a series connected with the release in August of the new paperback of The Last Seal my historical fantasy set during the Great Fire of 1666.