Clifford Garstang's Blog, page 3

April 1, 2025

2025 Reading–February and March

Highlights:

Until August by Gabriel Garcia Marquez is a posthumous novel by the great writer that probably shouldn’t have been published by his heirs. In a preface, we are told that the author was in bad shape mentally, but continued to write, but left instructions to destroy this manuscript. It wasn’t destroyed, but they did wait ten years before deciding to publish it. It’s about a happily married woman who travels some distance each year to visit her mother’s grave, and on one visit she meets a man and sleeps with him.

Night Watch by Jayne Anne Phillips won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction last year, and I’m not sure why. The book is set during and after the Civil War in West Virginia and is told mostly from the point of view of a young girl, ConaLee. We also get a few other perspectives including that of her mother, an older neighbor woman, and her father. The most interesting aspect of the book is the institutionalization of the mother in an insane asylum in West Virginia, as her captor (called “Papa” by ConaLee, although he isn’t her father) apparently needs to get rid of her. Why isn’t clear, because he’s just taking off anyway, and has stolen anything of value she had. The plot turns on a significant coincidence, and that, in my opinion, ruins the book’s plausibility.

Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry is a beautiful, poignant book, though as dark as any I’ve read of late. Two Irishmen, who have trafficked in drugs their whole lives, are sitting in the port at Malaga waiting for the ferry to Tangier, hoping to find the daughter of one of the men. The girl fled her home several years before when her mother died, and couldn’t bear to stay with her father. Besides being heart-breaking, the book’s language is stunning and fresh.

Also:

The Lightness of Water by Rhonda Browning White is a collection of short stories, some linked, set in Appalachia.

Rainbow Man by David Berner is a short novel about a widower who meets a woman with a complicated past while on a trip to Spain.

Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst by Robert Sapolsky is a very long book about the neurobiology of behavior.

March 31, 2025

Words, words, words

What’s with all the words?

In Act 2, Scene 2 of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Polonius, attempting to learn the cause of Hamlet’s distraction, asks the prince “What do you read, my lord?” To which Hamlet replies, “Words, words, words,” either to perpetuate his madness ruse or to disguise what he is in fact reading. Or, perhaps, to suggest that it doesn’t matter what he’s reading because it’s only words.

Words were very important to Shakespeare, obviously, and as a writer I feel the same way. We are always on the hunt for just the right word to use, and good writers seek to use words in a fresh and interesting way. I’ve been reading the work of an Irish writer, Kevin Barry (Night Boat to Tangier and The Heart in Winter to name two), and I’ve been blown away by his dazzling language.

I suppose it should go without saying that the choice of the words a writer uses is critically important, but what I want to talk about today is the number of words a writer uses. Non-writers almost never think about words as a number. Pages, sometimes, as in “That book is 600 pages, which is about 500 pages too many.” But usually not words. (A 600-page book might have between 150,000 and 300,000 words, depending on various factors of typography.)

Writers, on the other hand, think a lot about the number of words. In my MFA program, I was told that a debut novelist should aim for about 80,000 words, but that some genres, like fantasy, might go considerably higher. (The current trend is toward shorter books.) I also discovered that many literary magazines put word count limits on stories they’ll publish, many at around 5,000 words. Flash fiction magazines want stories that are far shorter than that, often capped at 1,000 words.

Not long after I finished my MFA program, I heard about something called NaNoWriMo, which stands for National Novel Writing Month. This is an event held every November in which participants commit to writing a 50,000-word novel in one month. Broken down by day, that would be an average of 1,667 words every day for the month, including Thanksgiving. Of course, that would be a short novel, given what I noted above, and it would probably not be very good, but in my opinion, for some writers, it’s not a bad idea to rush out a draft like that (or even a partial draft) to give you raw material to work with in the rewriting and editing process.

I remember a few years ago participating in an online discussion about NaNoWriMo in which I applauded someone who was racing toward their 50,000-word goal. A novelist I know who has published a few novels with major publishers dismissed the whole endeavor as amateurish and unserious. I argued that it’s not uncommon for successful writers to hold themselves to daily word counts, so why is NaNoWriMo any different? That writer dismissed daily word counts, too. I suppose the point was that art can’t be held captive to numeric targets. I didn’t want to prolong the argument, but I disagreed. To move to the next step in the process, you have to start with something—words, words, words. Even Shakespeare wrote first drafts.

This leads me, finally, to the point of this discussion. I’ve spent the last year promoting my novel The Last Bird of Paradise, which came out in February 2024, so I’ve done little new writing. Between the time that novel was finished and its actual publication (close to an 18-month stretch), I had begun researching and writing a new novel, but for most of last year it languished.

Earlier this year, however, I joined a critique group of writers with at least one published book to their credit. There are six writers in the group, and each week we read 15-20 pages of work by three of us, then meet on Zoom to discuss and offer suggestions to the writers. We are all writing very different books, but that doesn’t seem to matter to anyone because it’s all about the craft of writing.

It had been a very long time since I’d regularly shared work in progress with another writer. I had a couple of writing buddies after I graduated from my MFA program, and after that group fell apart I traded work with one other writer, but that too came to an end after a while. While I am extremely grateful for the feedback from the group, perhaps the most valuable part of the exercise for me is being held accountable. I’m expected to submit 4,000 to 5,000 words to the group every other week, so that is keeping me moving forward in the new project.

As of last week, I set a goal of 1,000 words a day. That worked out great for a few days, and then . . . life happened: a dentist appointment, a few Zoom meetings I’d committed to, etc. Still, I managed 4,000 words for the week, and that’s not bad. Given that other obligations will continue to crop up, if I can hit that goal every week, it won’t be long before I have a complete draft of this book and can begin the revision process.

And how long will the draft be? Good question. Currently, the work in progress is 20,000 words. I am thinking of this project as being a short novel, probably no more than 70,000 words. (For comparison, my three previous novels have been between 90,000 and 110,000 words.) If I continue to produce 4,000 words each week, I may have a complete draft by the end of the summer, although my critique group won’t have seen all of it until the end of the year. That’s the goal. It all depends on the words, words, words.

March 18, 2025

Remembering the Peace Corps

The first week in March is Peace Corps Week, commemorating the founding of the Peace Corps in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy. I’ve made a few leaps of faith over the years, but one that I am most proud of is my decision in 1975 to join the Peace Corps. That decision unquestionably changed my life.

In the spring of my senior year of college, I wasn’t sure what I was going to do after graduation. My father wanted me to take the LSAT (Law School Admission Test) and apply to law school, but I wasn’t excited about that prospect. I knew that I wanted to write, but because I had not been an English major, I felt I hadn’t read enough literature to be a writer. I thought graduate school in English would fill that gap, so instead of the LSAT, I took the GRE (Graduate Record Exam) and applied to a few schools.

At about that time, I was walking through my university’s student union building and saw a couple of people sitting behind a table draped with a Peace Corps banner. They were chatting with students who approached them, so I joined the conversation. I heard the recruiters talk about their experiences, which sounded exciting and a little scary, and I picked up a brochure and an application. The farthest away from home I’d ever flown at the time was to Arizona for a fraternity convention, so the idea of world travel, especially to a developing country, was daunting. But it didn’t cost anything to apply, so I filled out the form and sent it in.

Although the Peace Corps accepted me, they didn’t immediately have an assignment for me. That delayed the beginning of my adventure, but, fortunately, I had also been accepted into graduate school. With the blessing (and support) of my parents, I moved to Bloomington, Indiana (only about 50 miles from where they lived at the time), and began my studies. As much as I enjoyed the readings in my courses, I suspected I wasn’t cut out for an academic career, so almost immediately I began to think about what would come next after earning my MA in English. How would I support myself while finally beginning to write?

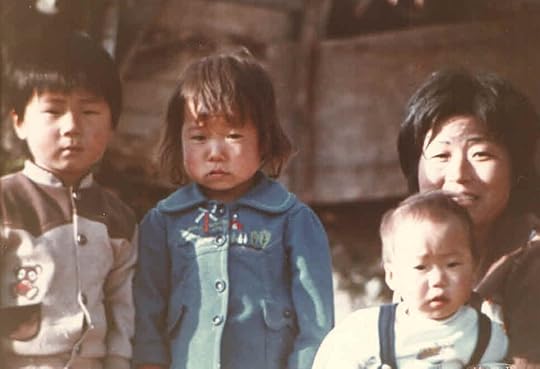

Then, midway through my first semester, a letter from the Peace Corps arrived. I had been invited to join a group of twenty-five volunteers going to South Korea to teach English at the university level to future English teachers. I knew nothing about Korea, but it sounded perfect. I don’t remember how long I deliberated over the offer, but I don’t think it was too long. I accepted and began making the arrangements to take a leave of absence from my MA program and move halfway around the world. (My parents were less thrilled, but that’s a story for another day.)

In January of 1976, I flew to San Francisco for our group’s “staging”—a process of meeting Peace Corps staff face-to-face, completing some final paperwork, and getting various necessary inoculations. We also participated in a few sessions of basic language learning and an introduction to Korean culture, as well as the Peace Corps rules we’d be expected to follow. The highlight of those few days in San Francisco was dinner at a Korean restaurant. My first kimchi! I loved it from the first bite.

At long last, it was time to board our flight across the Pacific. We first flew to Tokyo and stayed one night at a hotel (I’ve stayed in countless international hotels since then, but I will always remember the Keio Plaza Hotel in Tokyo) before going on the next day to Seoul’s Kimpo Airport. We were met at the airport by Peace Corps training staff and ushered to an inn near the Peace Corps office in downtown Seoul, followed by instructions on how to travel by bus in two days’ time to another city where our two months of training would take place.

As I recall, that first day in Korea was bitter cold, but I was keen to explore the area. I must have been given a map, because I found my way to Geyeongbok Palace and strolled around the grounds. I could scarcely believe I was in the middle of this ancient culture that was so unfamiliar to me, and that set the tone for the rest of my two years in the country.

Our training consisted of Korean language lessons, learning how to teach English conversation, and classes in Korean culture and history. Once our training was completed, we were official Peace Corps Volunteers and were sent off to our assigned sites. My site was a university in the capital city of a southwestern province known for its delicious cuisine. After those intense training months with my fellow volunteers, getting on a bus by myself to go alone to take up my job was a shock. I remember being very lonely for the first few weeks until I settled in, learned my way around, and made friends.

The next two years are a blur of amazing experiences including exploring historic sites in Korea, improving my Korean, deepening friendships, and also visiting other countries in East Asia including an extended trip to Japan after my first year and a longer jaunt in Southeast Asia after the completion of my service. Scroll down to see a few of the many photographs I took during my time in Korea.

I said at the outset that joining the Peace Corps changed my life. It would take a whole book to explain what I mean thoroughly (not out of the question for a future project), but here are some short answers:

Because at the time South Korea was a poor country and still recovering from its war with North Korea, living and working there opened my eyes to the harsh reality in which much of the world lives. I believe my service made me a more empathetic person and ultimately influenced my goal of working for the World Bank, an organization with the primary goal of alleviating world poverty.Studying the Korean language was also eye-opening: while I had taken some Russian in college, the Cyrillic alphabet is somewhat recognizable to an English speaker, but the Korean writing system is completely different. Since then, I have been fascinated by other East Asian languages, especially Chinese and Japanese.The experience of living in another country made me want to have an international career, and that ambition is what motivated me to finally take the LSAT and apply to law school. I believe my Peace Corps service probably helped me get into a good school and also may have helped me get a great job with a law firm afterward. It certainly influenced the management of that law firm, after I’d spent two years in the main office, to assign me to work in their Singapore office, where I remained for many years.Finally, when I finally turned my attention to writing fiction, my experience in Korea and everything that flowed from it gave me plenty to write about. I have no idea what kind of work I might have produced if I had stayed put in Indiana without having the adventures that life brought my way.Recently, I was invited to a college campus to speak with undergraduates who were considering applying to the Peace Corps. I was only on campus for an hour or so, but I enjoyed talking with the young men and women about their interests and sharing with them some of my own experiences.

In my opinion, there is no question that the Peace Corps has been an important tool for American diplomacy. Not only have thousands of people like me had an opportunity to learn about other countries and provide needed skills to their hosts, but we have also brought home with us what we learned about the world outside the United States.

In the current environment of an administration that is making wholesale and seemingly random cuts throughout the government, I am worried about the future of the Peace Corps. Given what has happened at USAID, it’s clear that President Trump doesn’t understand the value of fostering relations through development aid. I’m hopeful that the bipartisan support the Peace Corps has enjoyed in Congress over the years will stop the administration from making a grave mistake.

March 8, 2025

International Women’s Day

Celebrate International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month with these books by or about women!

March 3, 2025

THE LAST BIRD OF PARADISE is on sale!

Wow. My novel, The Last Bird of Paradise, celebrated its first birthday (February 22), and my publisher is giving YOU a present. For two days only, March 3 and 4, the Kindle version of the novel is just 99¢.

Winner of an International Impact Award, a Maxy Award, and a Maincrest Media Award, The Last Bird of Paradise is a powerful story about ambition, exploitation, and the ways we deceive ourselves.

Two women, nearly a century apart, seek to rebuild their lives when they reluctantly leave their homelands. Arriving in Singapore, they find romance in a tropical paradise, but also find they haven’t left behind the dangers that caused them to flee.

In the aftermath of 9/11 and haunted by the specter of terrorism, Aislinn Givens leaves her New York law practice and joins her husband in Southeast Asia when he takes a job there. Seeking to establish herself in a local law firm, Aislinn begins to understand the historic resentment of foreigners who have exploited the region for centuries. Learning about the turmoil of Singapore’s colonial period, she acquires several paintings done by an English artist during World War I that she believes are a warning to her. The artist, Elizabeth Pennington, tells her own tumultuous story through diary entries that come to an end when the war reaches the colony with catastrophic results. In the present, Aislinn and her husband learn tragically that terrorism takes many shapes when they are ensnared by local political upheaval and corruption.

In a lyrical blend of historical and contemporary drama, The Last Bird of Paradise explores the consequences of power imbalances-both domestic and geopolitical, against a lush, tropical backdrop. Clifford Garstang, author of the award-winning novel Oliver’s Travels, once again draws on his decades of experience in Asia to tell an unforgettable story of romantic intrigue.

Reviews

“Aislinn Givens leaves a settled life in Manhattan for an unsettled life in Singapore. That painting radiates mystery and longing. So does Clifford Garstang’s vivid and simmering novel, The Last Bird of Paradise.” -John Dalton, author of Heaven Lake and The Inverted Forest

“Garstang’s sympathetic imagination transports us in the manner of my favorite kind of fiction – that which convinces the reader of setting and character not because of the author’s resemblance to the protagonist but because the author is a virtuoso shapeshifter and spell weaver.” -Robin Hemley, author of Borderline Citizen: Dispatches from the Outskirts of Nationhood

“Clifford Garstang brings his experience as an attorney in Singapore to enrich a story of two women, a century apart, living parallel lives, linked by artwork that appears to come alive. Part history, part romance, part corporate intrigue, The Last Bird of Paradise is well written and propulsive-I didn’t want to put it down!” -Daphne Kalotay, author of The Archivists

“The Last Bird of Paradise is two stories of women from different periods of time and of different circumstances, but it serves to illuminate gender politics, geopolitical forces, and the results of power imbalance in many forms. Garstang gives us characters and settings that are microcosms of these forces, so the book doesn’t become didactic, but instead, offers complexity and nuance.” -Danielle Hanson, Tupelo Quarterly

Sales like this don’t happen very often, so if you’re a Kindle user, I hope you’ll take advantage of it. Paperback copies are still available, of course. Order from your favorite independent bookstore or Bookshop.org.

January 31, 2025

2025 Reading–January

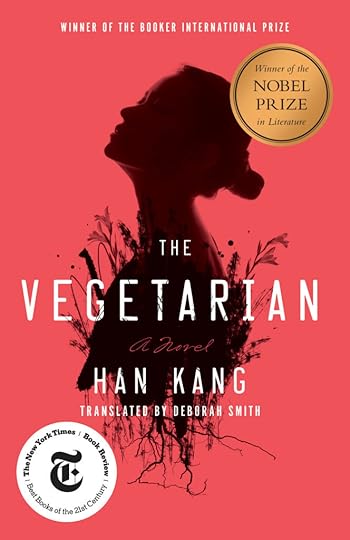

The Vegetarian by Han Kang

The Vegetarian by Han KangThe Vegetarian by Han Kang. I was asked to moderate a discussion of this book in February, so I needed to reread it. It comprises three linked novellas narrated by three different people but focused on a young woman who undergoes a deepening mental break down. It begins with her deciding, after a gruesome dream, to become a vegetarian, a decision that meets with resistance from her husband and her family. The second novella, her sister’s husband becomes obsessed with her and asks her to be a model in the piece of video art he has conceived, which pushes her further toward the edge. And in the last section, she’s in a mental hospital and is visited regularly by her sister, but she steadily gets worse. It’s a powerful, but very dark, story about violence and subservience.

Greek Lessons by Han Kang is another novel by the Nobel Prize winner. It disappoints in some ways. The two main characters are a woman who can’t speak (for, apparently, psychological reasons) and a man whose eyesight is failing. The woman is taking lessons in ancient Greek from the man because she hopes that the vastly different language (Korean is her mother tongue) will jog her power of speech loose, as it had once before when she studied French. The man, also Korean, was taken to Germany by his family when he was 15 and studied Greek and Greek philosophy there, but he’s come back to Korea as an adult in part because of his vision. I do wish the author spent more time on setting, as Seoul is basically invisible to the reader. There is an interesting exploration of language and the senses, but it all feels very cold.

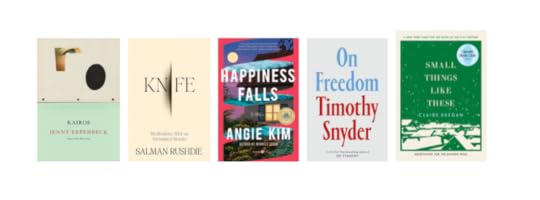

The White Book by Han Kang is a short volume that is called a novel, but to me it’s something else. A meditation on white things, it is apparently an autobiographical reflection on the brief life of Han’s sister, who was born prematurely and died within hours. The language is lyrical and the subject moving, but as a novel it’s unsatisfying.

The Magic Kingdom by Russell Banks was published not long before Banks’s death. The conceit here is that Harley Mann, an elderly real estate broker, is speaking his story into a tape recorder (and given that I listened to the audiobook, that seemed perfectly natural). Mann was a boy when he and his mother and siblings came to live at the New Bethany Shaker plantation in Florida. I knew very little about the Shakers, so much of the history of that Christian sect was new to me, and I found it fascinating. This group lived on 7,000 acres and did all manner of agricultural work to grow food in order to feed themselves and to sell to earn the funds to sustain the colony. It quickly develops in the telling that Mann became infatuated as a teen with a woman several years his elder, and what we hear is largely about their relationship.

On Tyranny by Timothy Snyder is a short book subtitled “Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century,” and I read it because last month I read a longer work by the author, On Freedom, and wanted more. Published in 2017, it anticipates the horror-show that the first Trump administration became and that the second one promises to be. The “lessons” are helpful tips for surviving an authoritarian regime.

O Monstrous World! By Josh Woods is a collection of quirky stories. There’s some horror and some supernatural events here and a good bit of humor thrown in.

Tremor by Teju Cole is a novel about a photographer who teaches at Harvard. Much of the book reads as a discourse on art and music, with themes that showcase the white mistreatment of African cultures. Inside the polemic there is an interesting character, one who is married to a Japanese-American woman but who also once had an affair with a man, and also had a very close friendship with another man. He loves African music and on a trip to Nigeria makes regular visits to a night club to hear music. In the middle of this relatively short book is a 50-page chapter that consists of vignettes in the voices of residents of Lagos. It’s unclear to me what the point of this chapter is. Overall, it’s disappointing as a novel, but I’m intrigued by the main character.

January 29, 2025

Happy New Year!

Welcome to the Year of the Snake

Welcome to the Year of the SnakeI have never put any faith in Western astrology, and I couldn’t tell you any of the supposed hallmarks of my own astrological sign (Sagittarius). However, having spent so much time in Asia, I’m a little more familiar with the Chinese Zodiac, mostly because it has a more prominent place in the culture than does Western astrology.

For example, the Chinese New Year (also known as the Lunar New Year or, in China, the Spring Festival [春节]) is an important holiday every year in Singapore (where I lived for many years) and other East Asian countries. It is generally celebrated over several days and during that time pretty much everything comes to a stop.

This year, the New Year falls on January 29, when we will welcome the Year of the Snake. Possibly this is an auspicious year for me, because I was born in a Snake year. Or maybe not. The Chinese Zodiac runs in twelve-year cycles, each year assigned to a different animal: Rat, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Sheep, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, Pig. (Read more about the Chinese Zodiac here.)

Because the festival is so important in Singapore, it was a useful dramatic tool for me in writing The Last Bird of Paradise, which is set there. The book is a twined narrative of contemporary and historical stories, and the festival plays a prominent role in both. For example, the Singapore Mutiny, which is a climactic event in the novel, occurred on the Chinese New Year in 1915. Similarly, the festival also ushers in the climax of the contemporary narrative.

In fact, when I returned to Singapore a few years ago to do research for my novel, my trip happened to coincide with the holiday that year. I enjoyed making several visits to Chinatown to see the decorations and also to check out the goods available in the shops and from street vendors.

Tips for Writers: Using Holidays in FictionWriters frequently use holidays in fiction for a variety of reasons. An approaching holiday may impose a deadline which, like a ticking clock, creates suspense. What might the characters have to accomplish by the holiday and what are the consequences if they don’t get it done? Holidays often involve family gatherings, and such gatherings are always potential sources of tension. We also often approach holidays with heightened anticipation, and if the holiday disappoints a character, he or she may react in ways that add complication to a story.

Besides my use of the Lunar New Year in The Last Bird of Paradise, I have frequently used holidays in these ways. In my novel Oliver’s Travels, the main character goes to his girlfriend’s family’s home for Christmas dinner and brings his mother along. His mom has a drinking problem and so does the girlfriend’s aunt. The result is a comic scene that reverberates for some time. I also included a tense Christmas dinner in a favorite story of mine, “Pluck,” which appears in my collection House of the Ancients and Other Stories, in which two former rivals are both invited guests at the same feast. In another story in that collection, “Last Call,” a high school reunion exposes a lingering conflict that has a tragic outcome.

For more on using holidays in fiction, you might be interested in this article, “5 Ways to Use Holidays in Your Story.”

Speaking of Oliver’s Travels . . .

Even though my novel Oliver’s Travels came out almost four years ago, reviews occasionally pop up on Goodreads and Amazon. Here’s one from “Dragonfly Reads” that made me smile:

“Oh, honey, this book had me hooked like gossip at a church potluck! Ollie Tucker’s journey is one wild ride, bless his heart. He’s off chasing family secrets, and you just can’t help but root for him, even when he’s stumbling through life like a baby deer. The way Clifford Garstang paints the picture is so sharp I could almost feel the heat of the road under my sandals. If you love a story with grit, heart, and a little bit of sass, this one’s a keeper!”

I appreciate all the reviews of my books, but this one will be hard to top!

That’s it for this letter. Happy Year of the Snake!

January 15, 2025

The Art of Storytelling

Auditor and Narrator: The Magic Kingdom by Russell Banks

Auditor and Narrator: The Magic Kingdom by Russell BanksNot long ago, I wrote in this space about Ann Patchett’s recent novel, Tom Lake. There were many aspects of the novel that I appreciated, but the one thing that prompted me to share my admiration for it was the point-of-view choice that Patchett made. The novel is narrated by a married woman with three grown daughters who is recounting the story of her life and, in particular, her long-ago love affair with a man who became a famous actor. What made this choice noteworthy for me was that it was clear from the outset that the woman was telling this story to her daughters—not some faceless reader, as with many novels—but real people who not only react to the narrative but also help shape it in the way the narrator uses language and makes decisions about what to leave out or emphasize.

In discussing the novel and the notion that in it the reader has a clear idea of to whom the story is being told, I recalled a workshop I took many years ago with Russell Banks (perhaps best known for his novel Cloudsplitter). Banks suggested that writers of fiction should consider the fictional auditor as carefully as they do the narrator. He gave the example of imagining himself as a boy lying in bed at night telling a story to his brother. The identity of the auditor would affect the way he tells the story, the language he uses, and the details he chooses to include.

I’m reminded of this lesson now because I’ve just finished reading Banks’s last novel, The Magic Kingdom, which was published not long before his death. Set in Florida, the book’s title is clearly a reference to Disney World, but also refers to a Shaker colony that preceded Disney World on the same site. The structure of the novel is of the “found manuscript” variety. A fictional writer, Russell Banks, has found a box of reel-to-reel tapes recorded by an elderly real-estate broker, Harley Mann, and invites us to listen to those tapes. At the end, the fictional Banks provides some additional context that adds resolution to the story that the tapes have told.

So, the narrator of the novel is the man speaking into a tape recorder. This, obviously, isn’t quite the same as telling the story of your life to your children. He is telling about a significant period of his life when he lived in that Shaker colony, but how does the recorder shape his narrative?

Fairly late in the telling of his story, Harley addresses this question. “Because I don’t know who I’m telling this story to, I’m unsure of what to say and what to leave out, what to describe and what to pass over, how much background to provide and how much to forgo.” This is exactly the lesson that Banks taught in that workshop long ago. But Harley goes on. “I decided then, as now, that I was speaking to a listening angel of the Lord, though I don’t believe in angels or, for that matter, the Lord. But it’s a useful conceit. . . . [I]t’s as if my words were directed exclusively to a listening angel of the Lord and were merely being overheard, rather than heard, by whoever happened to be in the room.” Given that the whole narrative is something of a confession, this makes perfect sense.

Another Approach: The Vegetarian by Han Kang

Recently, a new bookstore in my town began an International Book Club, which, given my international work and travels, I find enticing. It’s a little difficult to find time to fit another book club’s reading into my schedule (I facilitate my own book club, which has been meeting monthly for fifteen years), but I’m going to try. I was away for the first session, which was a discussion of The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgkov, which I’ve never read. The bookstore owner is from Russia, so she led the discussion. I did attend the second session because I had already read the book to be discussed, Prague by Arthur Phillips. (I had read the book, which is set in Budapest, not Prague, at the recommendation of a friend who actually led the discussion at the store.) I missed the next meeting because of travel, when the group discussed One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, which I would gladly have reread. Because of a local showing of the movie based on Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These, which I read last summer, the group talked about that book next.

For February, the IBC will discuss The Vegetarian by Han Kang, winner of the 2024 Nobel Prize for Literature. Because of my experience and long-held interest in Korea, I was asked to moderate the discussion, so I’ve just reread the book and have also read other work by her.

The book is actually three linked novellas that were first published separately in Korea. The three parts have different narrators, all focused on their interactions with Kim Yeong-hye, a young woman who, because of a dream, has suddenly become a vegetarian. In the first part, her husband has to deal with the change that has come over his wife and the mental breakdown that follows. In the second part, we now see Yeong-hye from the perspective of her sister’s husband, an artist who convinces her to be a model in his latest video project. And in the last part, Yeong-hye’s sister struggles to understand and care for Yeong-hye who is now confined to a mental hospital and refuses to eat, believing that she is becoming a tree and so only needs water.

While the auditor of these narratives isn’t clear, what’s interesting to me is that novel’s main character is seen primarily through the eyes of the three narrators. Her dark dreams, which are rendered in italics, do give us some insight into her thoughts and what is behind her descent into madness, but we don’t otherwise know what she’s thinking. She doesn’t even say much. Despite remaining outside of her consciousness, the portrait is literally three-dimensional because of the very different perspectives of the three narrators.

I’m looking forward to the discussion. As part of my involvement, I also provided a blog post that you may find interesting, along with a list of recommended books: Understanding Asia One Novel At a Time.

Flutes Reading Series in Lynchburg, VA

If you happen to be in or near Lynchburg on Sunday, January 19, please join me for the Flutes Reading Series at the Flutes Wine Shop and Lounge. I’ll be joining non-fiction writer Marilyn Bousquin at 4:00 pm for the latest edition of this new reading series. I look forward to reading from and discussing my book, The Last Bird of Paradise.

January 1, 2025

Out with the old . . .

Happy New Year! I know I’ve been quiet for a while, but here I am with a year-end report and some expectations for the coming year.

Goals met, goals setIf you’re interested, last year at about this time I posted some goals for 2024, which you can see here. I didn’t meet many of the goals (no poems, no essays, no draft of the new novel, and not much teaching), but I did manage to usher my novel The Last Bird of Paradise into the world (with very positive reactions) and I made two trips to Europe (Ireland in September and Germany in December). Here are a few images from the trip to Leipzig.

My goal for 2025 is to make substantial progress on my new book project. I have written some, but I have a long way to go with it, and I’m in the midst of interesting research that will help guide me as I move forward. (It’s too early to say much about the project, but I was doing research in both Germany and Ireland. That’s as much of a hint as I’ll give at this point.) I’m not committing to finishing a draft of the book, although that’s possible. If I also manage, at long last, to draft a personal essay, that would be great. We’ll see.

2024 ReadingI read more books in 2024 than I did in the prior year, mostly because I was one of the judges for the Library of Virginia Literary Award for Fiction (an award I won in 2013). You can check out brief reviews of some of the books I read here. Here are some of my favorite books from my year’s reading:

For Writers (and Curious Non-writers): The 2025 Literary Magazine Rankings are here!

For Writers (and Curious Non-writers): The 2025 Literary Magazine Rankings are here!When I started submitting short stories to literary magazines back in 2003, shortly after I graduated from my MFA program, I had no idea what I was doing. Eventually I developed a tiering strategy: making simultaneous submissions to magazines of roughly equal reputation. But how to evaluate reputation?

Eventually, I created a ranking system for magazines that published fiction, taking data from ten years of anthologies published by the Pushcart Press, an organization that awards prizes to the best short work published in the prior year. It was a useful tool for my tiering strategy, and so I shared that list on my website. It wasn’t long before writers of poetry and nonfiction clamored for similar lists, and I created those.

At the end of each year, when the new Pushcart Prize anthology comes out, I update all three lists, which have become very popular. The lists for 2025, which I posted on Christmas Day, can be found here. Please share with your writer friends!

Social MediaAs a Small Press author, I depend on Social Media, in addition to this newsletter, to get the word out about my books. It can be addictive and exhausting, especially when there is so much noise on these platforms. I’ve always enjoyed Twitter/X and have gradually built a following there, but since Elon Musk took it over and turned it into a disinformation machine for his own ambitions, I can no longer support it. I have stopped posting there. I’m also on Facebook, Instagram, and Threads—all owned by Meta—but the best alternative to Twitter/X I’ve found is BlueSky. If you do Social Media, look for me there: @cliffgarstang.bsky.social

AppearancesSince my last newsletter, I’ve made a few appearances promoting The Last Bird of Paradise. In November, I gave an Author Talk at the R.R. Smith Center in Staunton for the UVA Osher Lifelong Learning Institute. Because few people know much about Singapore, which is the setting for the novel, I shared a slide presentation about the history and current situation there, as well as talking about the book.

Also in November, I was invited to Anne Arundel Community College in Maryland as part of their Writers Reading series. The College Creative Writing program invites three writers each semester to come to read from their work. I read two excerpts from The Last Bird of Paradise, and a shorter excerpt from Oliver’s Travels because I thought college students would be able to relate to it. The reading was great fun and was well-received.

My next appearance is the Flutes Reading Series at Flutes Wine Lounge in Lynchburg, Virginia, on January 19 at 4:00 pm. I’ll be reading from The Last Bird of Paradise.

That’s it for now. Thank you for reading, and best wishes for a great 2025!

December 31, 2024

2024 Reading–November and December

Knife: Meditations after an Attempted Murder by Salman Rushdie was my book club’s selection for November. The memoir is a gripping account of the knife attack on Rushdie as he was about to speak at Chautauqua and his subsequent long road to recovery. Some of the book is about the absurdity of the motivation for the attack, but a lot of it is about the support he received from his relatively new wife. So we also learn how they met and what their relationship is like as he heaps praise on her. While it was a fascinating book, and one that I’m sure must have been therapeutic for him to write, it seemed odd to me at times. He writes that at several crucial moments during the attack and its aftermath passages from literature came to him that, in the book, he quotes. I’m sure he’s a lot smarter than I am, but if I remember anything from things I’ve read, it’s just snippets, and I’m certainly not thinking about those snippets, or trying to remember whole passages while I’m being attacked, or while a surgeon is probing my eye. Still, if you know anything about Rushdie and his career, this is a worthwhile read.

Other Rivers: A Chinese Education by Peter Hessler is a book I was asked to review for the Peace Corps Worldwide website. I’ve read all of Hessler’s previous China books since his first one over twenty years ago, River Town, about his experience as a Peace Corps Volunteer in a Chinese university. Here, two decades later, he is teaching in China again after spending time as a journalist and author of several books. China and Chinese students have changed, he discovers, and he’s able to draw contrasts. Interestingly, he’s still in touch with his students from his Peace Corps days, so he’s also able to track what happened to them. Because Hessler’s Peace Corps experience was so similar to my own—I taught in a Korean university twenty years before he first went to China—I find a great deal that’s familiar. The book is also enlightening because he was in China during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, and describes China’s response to it. Hessler is a terrific writer, and I enjoyed the book.

Alexander the Great: His Life and His Mysterious Death by Anthony Everitt is a biography of the man who conquered a large swath of the known world in the 4th Century BCE. While I was interested in the man and his times, I found the long accounts of the battles his army fought under his command to be tedious. He was always at the front, so these battles demonstrated his bravery (or perhaps his death wish), but the detail seemed unnecessary to understand the man. What was more interesting, in a macabre way, was the brutality with which he dealt with opposition and even seemingly minor slights. I’m glad I read it, but the book could have been half as long.

Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, translated from German by Michael Hoffman, is a novel that my book club is reading for January, but that I would have read anyway. Beginning in East Berlin before the fall of the Berlin Wall, the story recounts the affair of a young woman and a much older novelist. The narrative is a recollection she has of their time together after she starts going through boxes of letters and items she receives following his death, presumably from the man’s wife. Her struggles dealing with the strict regime and then the sudden freedom after reunification are fascinating, as are the tantrums the novelist throws as he deals with his obsession and jealousy.

On Freedom by Timothy Snyder was my book club’s selection for December. I had not read Snyder before, but I was struck by the way he inserted himself into a book that is essentially a philosophical treatise. He recalls his childhood and the times spent on his grandparents’ farm, his education and academic achievements as he studied Eastern European governments and history. His man personal visits to Ukraine feature prominently, as do his conversations with various East European leaders and thinkers. Ultimately, he is drawing a distinction between negative freedom and positive freedom, which is real freedom, he seems to be saying. The concluding chapter is a useful roadmap for how America might come closer to achieving positive freedom.

The Bamboo Wife by Leona Sevick is my friend Leona’s second poetry collection, this one from Trio House Press. Sevick’s poems are very personal, as she frequently writes about her family, sometimes with intimate detail. The early poems in this collection are about a visit she paid to Jeju Island in Korea, a trip that brought back memories—very different from Sevick’s—of my own visits to the island during my time in Korea.

The Last Lap by William Walker is an interesting account of the life and death of race car driver Pete Kreis, a cousin of the author. Kreis grew up in Knoxville, one of the sons of a prominent Tennessee businessman, and early on became obsessed with cars and then with racing. When he died in an accident at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1934, there were questions about what might have happened. Did he crash intentionally? Walker seeks to answer the question at the same time as he recounts the early history of racing in America.