Clifford Garstang's Blog, page 23

September 2, 2021

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Part 7

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: After the World Bank

Although I liked my job very much, especially the travel (exhausting though it could be), I eventually decided that I wanted to turn my attention to writing fiction full time. Being a spare-time writer is admirable, but it didn’t look like it was something I was going to be able to pull off. So, I quit my dream job, sold my condo, and moved 150 miles away into an idyllic setting in the country, and began writing.

Even after I left the World Bank, however, I continued to work occasionally as a consultant, particularly on projects I’d been handling before. Project managers would ask me to join them on a trip to Jakarta or Beijing or wherever, and I would make the arrangements and go, with tickets and visas and so on taken care of by the Bank.

In this way, I made many more trips to China even after I was no longer a Bank employee. I continued to study Chinese on my own, off and on, making very little progress. As noted early in this series, I also studied other languages: Spanish in anticipation of spending some time in Mexico and later French before I went to a writers’ retreat in Southwestern France.

I enjoyed both of those classes at the local community college, free to me because I was an adjunct teacher of English at the time, and eventually noticed that they offered a Chinese class, too. The first semester of beginning Chinese looked too easy, and there was no second year, so I enrolled in the second semester of the beginning course, which was taught online. Frankly, because of all the time I’d spent with the language up to that point, it wasn’t difficult. The college didn’t offer Chinese beyond the second semester, however.

What the Zhang Boys Know

What the Zhang Boys KnowMeanwhile, my fiction writing has always had something of an Asian flavor, as China and Korea are not far from my mind. In my first collection of short stories, In an Uncharted Country, one of the stories is about a couple who go to China to adopt a baby. That story was inspired by the trip I described earlier in this series in which I was assisting friends who were adopting. Another story in that collection is based on a Korean fairy tale I had translated as a language-learning exercise years earlier. My second book, What the Zhang Boys Know, is set in a condo building in Washington DC, but is focused on Zhang Fengqi, an immigrant from Shanghai, and his family. Thematically, the book also touches on the subject of being witness to tragedy, a theme that was partly inspired by a visit I took to Nanjing, China (site of the Nanjing Massacre of 1937-38) when I was still traveling regularly to China. My first novel is set partly in Korea, my second novel is set partly in Singapore, and the book I’m currently working on is sent entirely in Singapore, and the Chinese language and culture is a big part of that project.

My language studies have drifted over the last ten years or so–prepping for a trip to Europe or Korea–because I’ve been focused on my writing. That changed when the pandemic struck.

Next up, the conclusion of My Mandarin Chinese Journey.

September 1, 2021

I’ve Got Questions for Cindy Maddox

Editor’s Note: This exchange is part of a series of brief interviews with emerging writers of recent or forthcoming books. If you enjoyed it, please visit other interviews in the I’ve Got Questions feature.

In the Neighborhood of Normal by Cindy MaddoxWhat’s the title of your book? Fiction? Nonfiction? Poetry? Who is the publisher and what’s the publication date?

In the Neighborhood of Normal by Cindy MaddoxWhat’s the title of your book? Fiction? Nonfiction? Poetry? Who is the publisher and what’s the publication date?In the Neighborhood of Normal. It is fiction, published by Regal House Publishing, release date 9/1/21.

In a couple of sentences, what’s the book about?Back cover copy reads: Eighty-two-year-old Mish Atkinson from Fair Valley, West Virginia, is determined she’s going to make something of the time she has left on this earth. When a text message on her new smartphone leads to an encounter with a woman she believes is Jesus, Mish is eager to obey the woman’s instructions to follow the love. She knows that Jeff, the gay pastor at her church, thinks she’s lost her marbles, but now that her husband is gone, she’s not going to let anyone put a damper on her sunshine. And when a pregnant teen needs her help, it doesn’t matter that she doesn’t know the difference between STDs and DVDs, she follows the love—in for a penny, in for a dollar, as she always says. Following the love is exciting and meaningful… until it costs much more than dollars and cents.

What’s the book’s genre (for fiction and nonfiction) or primary style (for poetry)?Women’s fiction or commercial fiction

What’s the nicest thing anyone has said about the book so far?Here are a few of my favorite quotes:

“In the Neighborhood of Normal is the exactly right read for this unprecedented post-Trump, knee-deep-in-Covid, uncertain moment.”

“It’s a story that reminds us of what we can do and who we can be when we look for and follow love.”

“I finished the book a few days ago and I can’t stop thinking about Mish. I just love her!”

“I love Mish. She feels like someone I know.”

What book or books is yours comparable to or a cross between? [Is your book like Moby Dick or maybe it’s more like Frankenstein meets Peter Pan?]I think it’s a cross between A Man Called Ove and Jan Karon’s Mitford series.

Why this book? Why now?I try to read some of those tough “important books” that everyone talks about, but sometimes I just need an escape. At the same time, I don’t like to read books that are just “fluff.” So I tried to write the kind of book I enjoy reading: a book with real characters who deal with real-life situations, but that still provides the reader with a fictional world she would love to join. I also wanted to tackle some difficult topics in a way that makes them accessible. With all the harsh realities we are facing right now, I want an escape into Mish’s worldview to provide a respite. All we have to do is follow the love.

Other than writing this book, what’s the best job you’ve ever had?I am a pastor in the United Church of Christ, the most progressive mainline Christian denomination. Being invited into the best and worst moments of people’s lives is a pretty amazing job. It also involves a significant amount of writing, with those weekly sermons to prepare.

What do you want readers to take away from the book?I want readers to be reminded that following where love leads may be a risky endeavor, but love is worth the risk.

What food and/or music do you associate with the book?I can’t write to music like many authors do, so I don’t have those associations from the writing process. But the main character, 82-year-old Mish Atkinson, likes Southern Gospel music. As for food, she refers to herself as “a bacon and eggs gal,” which means she doesn’t have time for sugar-coating. Ever since writing that line, I can’t see bacon and eggs without thinking of Mish!

What book(s) are you reading currently?I’m currently reading A Better Man by Louise Penny.

Cindy Maddox

Cindy MaddoxLearn more about Cindy on her website.

Buy the book from the publisher (Regal House Publishing) or Bookshop.org.

2021 Reading–August

Doesn’t everyone read more in August?

Best American Short Stories 2020

Best American Short Stories 2020The Best American Short Stories 2020, edited by Curtis Sittenfeld is the latest in this long-running series. I don’t read it every year, and in fact, have mostly used it only when I’m teaching a class in the short story. This year I have been holding tutorial sessions on the short story and for each session, I have paired a “classic” story from my syllabus that illustrates the session’s subject with a story from BASS 2020. I’ve chosen the modern stories for each session almost but not quite at random. The fact is that for most subjects—character or setting or dialogue, or whatever—any decent story will offer lessons that will be valuable. I can’t say that I’ve loved all the stories in the volume, but we’ve had good discussions about them, and it makes for a more lively analysis of the subject each session than if we were just reading an old, shop-worn classic.

River Weather by Cameron MacKenzie

River Weather by Cameron MacKenzieRiver Weather by Cameron MacKenzie is a collection of stories that the author asked me to blurb, and here’s what will appear on the book’s back cover: “The stories in River Weather manage to be both sensitive and transgressive, socially conscious and hard-edged. MacKenzie captures with exquisite detail the challenges of being a man in a world that’s gone to hell, coping with irresistible urges and impossible expectations. Like the work of Palahniuk and Ellis, these stories are riveting and bleed tensile masculinity. Crisp and hard-hitting, this book will leave you breathless.”

—Clifford Garstang, author of What the Zhang Boys Know

Teaching the Way by Steven T. Nelson

Teaching the Way by Steven T. NelsonTeaching the Way by Steven T. Nelson is a wonderful book that I was asked to blurb because I saw a much earlier draft several years ago. The author is a friend of mine, but I genuinely think this is a hugely valuable resource for composition teachers, especially someone first starting out. He uses Sun Tzu’s Art of War as a guiding principle and suggests the best way for a teacher to approach a class, to handle assignments, to conduct exercises, etc. In fact, the book includes a number of sample exercises that by themselves would be useful, and a suggested grading rubric. I had none of these tools when I taught composition, and I wish I had.

Pride of Eden by Taylor Brown

Pride of Eden by Taylor BrownPride of Eden by Taylor Brown asks the reader to make a decision: is it acceptable to break the law if your actions are morally right? The two main characters here seem to think it is. Malay, a woman from a military family and a veteran herself of the Iraq war, has found herself faced with this dilemma on more than one occasion—in Iraq, later in Africa when hunting poachers, and now in South Georgia. She’s working with Anse, a Vietnam vet and former jockey who has taken wild animal rescue to an extreme, hunting down and stealing big cats and other animals that he lets live on his property. Together, the two don’t let legalities get in the way of their efforts to do right by these animals, even at great bodily risk to themselves. My full review is forthcoming in Southern Review of Books.

The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley by Hannah Tinti

The Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley by Hannah TintiThe Twelve Lives of Samuel Hawley by Hannah Tinti is a book I’ve been meaning to read for some time. I can’t say I loved it, but it was reasonably engaging, mostly because of the voice of the young girl who is the primary narrator, Loo (short for Louise). She is living with her father in the town where her deceased mother grew up, and in the story, she is learning more about her parents and herself as she matures. We frequently are transported to the father’s rough past, however, and learn how he survived the twelve gunshots that have scarred him. That’s a little tedious, and I wondered if we really needed twelve. Couldn’t it have been the “Six Lives of Samuel Hawley”? There is something of a mystery surrounding the death of Loo’s mother, and that’s sufficient reason to keep reading, but after that is resolved I wasn’t sure I wanted to go on. Overall, there is the question of why the reader should care about Samuel Hawley. Yes, it’s mostly Loo’s story, but Samuel is a thief and a murderer who deserved all of the gunshot wounds he’s received. His daughter might just be better off without him.

The Reason for the Darkness of the Night by John Tresch

The Reason for the Darkness of the Night by John TreschThe Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science by John Tresch was my book club’s selection for August. It’s an interesting read and I learned a lot about Poe and the state of scientific knowledge in the first half of the 19th Century. While the main theme of the book is the “forging of American science,” along the way we are informed about Poe’s personal life as well as his work as a writer and editor. He was something of a celebrity at times—particularly after the publication of “The Raven”—but he was also always stretched for cash. He even declared bankruptcy at one point. He engaged in numerous literary feuds, which may have been a way for writers simply to claim the public’s attention, but that we’ll never know for sure. It’s a fascinating book that is a little dense, given Poe’s complicated belief system and the science that engaged him.

Bewilderment by Richard Powers

Bewilderment by Richard PowersBewilderment by Richard Powers is the follow-up to his very powerful, Pulitzer Prize-winning Overstory, but with much less of that book’s weight, in my opinion. My full review will appear in the New York Journal of Books, but here I will say that much of the book was fascinating. The main character, Theo Byrne, is an astrobiologist, someone who searches for life on other planets, so there is a lot of speculation about the universe, distant galaxies, and whether other life forms are looking for us. He is also a single father, his wife Aly having been killed in an automobile accident before the book begins. (Hmm, that’s how my own book, What the Zhang Boys Know, begins.) His son, Robin, is on the autism spectrum, but highly functioning most of the time. At one point, Theo, who is struggling with Robin’s behavioral problems, reaches out to his wife’s friend (and maybe lover, Theo jealously suspects), Martin, a neuropsychologist, to see if there isn’t something other than a drug that could alter Robin’s behavior. Robin is worked into Martin’s “Decoded Neurofeedback” experiment, with spectacular results. There’s more to the book, including the dangerous anti-science political environment, the manipulation of elections by a Trump-like President, a frightening virus—all things that feel too true. While the book falls short of Overstory, it does retain some of the fabulous wonder—bewilderment—with nature (Robin is obsessed) and carries that wonder out to the stars. It also has an important message: we’re killing off the animals and the planet along with them.

August 31, 2021

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Part 6

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Kazakhstan

Almaty, Kazakhstan

Almaty, KazakhstanAfter ten years in Singapore (minus the year I spent in Los Angeles), I left my law firm and enrolled in a mid-career Master of Public Administration program at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard to study international development. My goal was to use my international law background in one of the international development banks such as the Asian Development Bank or the World Bank. I spent one year at Harvard, and it was a wonderful experience. It was a hectic year, and I wasn’t able to fit a language class into my schedule while I was at Harvard, unfortunately.

Although I did make some connections at the World Bank that would ultimately prove useful, my first job after graduation was as a legal reform consultant on a US AID project in Almaty, Kazakhstan. (Technically, I was working for a Harvard consulting “firm” called the Program on International Financial Systems, a joint venture between Harvard Law School and the Harvard Institute for International Development.) The project itself was one thing—poorly designed, despite the fascinating subject matter—but living in Almaty was another challenge. I dredged up a little of the Russian I had studied in college, mostly just polite expressions, but our work was done through an interpreter. I never did learn any of the Kazakh language.

What was appealing to me about Kazakhstan when I was offered the job was its proximity to China—the two countries share a very long border, over 1100 miles. The relationship between them is complicated, in part because there is a large ethnic Kazakh population inside China as well as a very large Uighur community, a group closely related to the Kazakhs. (The two languages, Uighur and Kazakh, are both Turkic, and apparently mutually intelligible.)

I never looked into the details of the cross-border trade, but there was a fair amount of it, as Chinese goods were readily available in Almaty, and I would occasionally see Chinese men on the streets and understood them to be businessmen. Also, there was a decent Chinese restaurant that I went to now and then, giving me an opportunity to use a little of the language, although not for anything very challenging. Again, just polite expressions and ordering food.

I should mention that there is also a large ethnic Korean population in Kazakhstan owing to Stalin’s internal displacement policies before World War II. Stalin feared that Japan would infiltrate the Soviet Union via the Koreans who lived in Russia’s far Northeast, and, consequently, many were deported to Central Asia. There would be Korean women in the Almaty markets selling kimchi and other Korean food items, and there were a couple of Korean restaurants in Almaty at the time I lived there.

The year I spent in Kazakhstan didn’t help my Chinese abilities, but it did keep my interest in the language alive.

Next, Working in China

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Part 6

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: At the World Bank

When I returned from Kazakhstan—I chose not to renew my contract, or the project ended, or something—I moved to Washington DC. My plan was to seek out short-term consulting assignments while working on a novel. The consulting gigs that came my way all involved stays in Central Asia that were longer than I was interested in, so I turned them all down. I enjoyed wandering around Washington DC and writing. My apartment was in a nice neighborhood—not far from the Chinese embassy, as a matter of fact—and there was a lot to do.

At the recommendation of a former colleague, a San Francisco-based law firm approached me about coming to work for them in their planned Singapore office. Although it sounded like the work would be very similar to what I had already done, and wouldn’t feed my international development interests, at least not directly, I was intrigued. I went out to California to interview for the job. Just as that possibility was percolating, I was contacted by the World Bank and asked to interview for a position there. I jumped at that chance, and eventually, I started to work in the World Bank’s legal department.

This was the job I wanted when I left my law firm for Harvard, so I was thrilled. I was hired to work in the East Asia Division of the Legal Department, which meant that I would be working on projects throughout North and Southeast Asia. From the beginning, my primary responsibilities were for infrastructure projects, mostly power, in China, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Perfect. A few months after I started and got the hang of how working at the World Bank was different from anything else I had done, I began to travel to help put these projects together and negotiate them with the respective government departments.

Trips to Hanoi involved an overnight stay in Hong Kong and trips to Jakarta involved an overnight stay in Singapore, although generally, I opted for the airport hotel in those countries for convenience. Because China was the Bank’s largest borrower, my most frequent destination was Beijing, with side trips to other Chinese cities. Eventually, I also made trips to Lao PDR and Cambodia (via Bangkok) as well as Mongolia (via Beijing).

Because several of the lawyers in the East Asia Division worked on China projects, we asked the Bank to hire a tutor for us. The teacher, a native Chinese speaker, worked with us for a short time, and used the same textbook I had used in Singapore! Unfortunately, because we all traveled so much, these lessons didn’t work out too well and we eventually stopped. I continued to study independently, however, and got some practice on my visits to China, which were frequent. I also loved to stop by Chinese bookstores in Beijing and eventually bought other textbooks for self-study, although I can’t say I made much progress with them.

As a result of the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, I also began to travel to Korea regularly. Korea had not been a World Bank borrower for many years because of its booming economy, but the crisis forced them to reach out for balance-of-payments support. Because I was the only one in the department with Korea experience, I was assigned to work with the economic team to put our loans together and negotiate them. It was difficult work, but I was delighted to make many trips to Seoul over the course of a few years, until the crisis ended. My ability to speak Korean—rusty at that point, but functional—also came in handy.

For several more years, I traveled to China frequently. Being able to speak some Chinese was a huge comfort on those trips, as it made getting around simpler, and even just being able to go out to a restaurant and order dinner was a help.

Only once during those years did I travel to China for anything other than my World Bank work. Some good friends of mine were adopting a baby from China and they were nervous about traveling there. I volunteered to go with them, to help with the language and anything else they needed. We met up in Chicago, flew to Hong Kong via Tokyo, spent the night in Kowloon—an adventure in itself because they’d never been—and then flew on to Guangzhou and our ultimate destination, Nanning in Guangxi Province. It took several days to get the paperwork done at the US Consulate and then we flew home with the baby. Quite an experience and I do think having some Chinese made it a little bit easier.

Next: Further Study

August 30, 2021

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Part 5

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Singapore

As I was finishing law school, I interviewed for jobs with law firms. I was particularly interested in firms with international practices because of my own international experience. I received several offers and chose the largest firm I’d interviewed with because it seemed to me to offer the best opportunity to do international work. I moved to Chicago and got busy learning how to be a lawyer.

The department I was placed in at the firm did its best to give me “international” work, but this mostly consisted of small loans by the Chicago offices of international banks. There wasn’t really much international about it except for the names of these clients. That was okay, though, because all of my other work was providing me with great training in the commercial lending field, which was keeping us all very busy. I liked the people I worked with and the projects we worked on.

After I’d been at the firm about a year, the management announced that they would be opening a Singapore office. (They already had three offices in the Middle East about which I knew little.) I immediately approached the partner who was going to be leading the new office to let him know of my experience in Asia and of my interest in eventually working in the region. He was a wonderful older gentleman and we got along very well. He was keen to hear about my Peace Corps experience and my visit some years earlier to Singapore on my backpacking trip through Southeast Asia. I was glad to have made that connection. To help him in the new office, the firm had hired a senior associate from a New York firm, and off they went to build a practice.

A year or so later, I got a call from the firm’s Managing Partner inviting me to lunch. This was unheard of, and I had no idea what to expect. I arrived at his spacious office, and together we went up to the private club at the top of our office building where we had lunch, and he explained why he’d wanted to talk to me. It seemed that the senior partner who had opened the Singapore office was being replaced by the associate they’d hired to help him, which meant they needed a junior lawyer to move to Singapore to work with him. He’d heard of my interest from various sources—I don’t think he told me who. Did I want to go?

Hell, yeah, I wanted to go. By the end of the year—on the last day of the year, to be precise, for tax reasons—I arrived in Singapore, and in early January I was at work in our two-lawyer office. (When I arrived, the senior partner had not yet left the country, and I was able to solidify my connection with him and to meet some members of his family before he moved back to the U.S. That connection would be relevant in the coming years.)

All of which is a long-winded explanation for how I ended up in Singapore. But being there presented a new language learning opportunity for me.

I don’t think I’d been living in Singapore very long when I decided to take Chinese classes. The truth was that Chinese wasn’t really necessary for foreigners. English was and still is the language of business there. Still, given that a majority of the local population was of Chinese ancestry and many of the shops posted signs in Chinese, it seemed like a handy skill to have. In fact, Singapore has four official languages: English (because it was once a British colony), Mandarin (because of the sizable Chinese population), Malay (because of the large Malay population and because Singapore was, for a time after independence from the UK, part of Malaya), and Tamil (an Indian language, because of the many people of Indian descent in the country as a result of India also being a former colony of the UK).

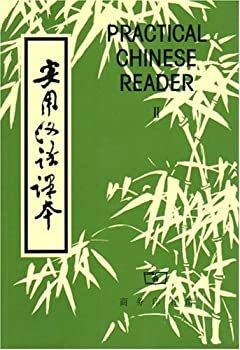

I don’t remember the name of the language school I went to—there were many such schools offering similar classes to foreigners—but I do remember that the class was small and operated on a similar method to the one I used when I taught English in Korea: repetition of words and phrases following exercises in the textbook, Practical Chinese Reader I.

I still have that textbook! (See the image above.) In fact, I later acquired the other 5 volumes in the series.

Over the course of the decade I spent in Singapore, I studied Chinese off and on, not very diligently and not very successfully. I didn’t need it for work or daily life, I went to China only once during my time in Singapore, although I paid a few visits to Hong Kong and Taiwan, and my time in the country was interrupted by a posting for over a year in Los Angeles, which really threw me off.

Nonetheless, the studying I did during those years laid the groundwork for future attempts to learn the language.

Next up: Speaking Chinese in . . . Kazakhstan.

August 27, 2021

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Part 4

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Japanese

After living in Korea for two years, I returned to the United States and went back to graduate school to finish my MA in English. (I did one semester before I went abroad.) Having already satisfied my language requirement for that degree (German, in my case), I thought I’d like to continue studying Korean. However, Indiana University had dropped their Korean language program for some reason so the course I wanted was unavailable.

Still, I didn’t want to waste the opportunity to study a language, and my time in Asia had made me interested in all things Asian. On a backpacking trip after finishing my service, I’d visited Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, and Singapore (among other places), all Chinese-speaking countries, but I’d also spent some time in Japan, which I found extremely appealing. So, I elected to take Japanese at IU. Because it didn’t fit in my course load needed to get the MA, I asked permission to audit the class, which was granted. The teacher even let me take the exams, which kept me motivated.

I haven’t retained much from that one year of Japanese other than my textbook, but I did learn a lot that was useful. For one thing, I learned that Japanese grammar is nearly identical to Korean. Linguists say the languages aren’t related, but that’s hard to believe because of the similar grammar. Also, like Korean, Japanese uses many Chinese characters to supplement their phonetic alphabets. (Yes, there are two alphabets, one for Japanese words and one for loan words.) And there are a great many words that are borrowed from Chinese, often the same ones used in Korea. (For example, the word for university in Chinese is 大学校—usually shortened to just the first two characters, 大学, or in the Pinyin Romanization system, Da Xue Xiao, or the shorter form, Da Xue; those three characters are also used in Korean and Japanese, although they are pronounced slightly differently. In Korean they are pronounced Dae Hakkyo. In Japanese they are Dai Gaku.) Much has been written about both Sino-Korean and Sino-Japanese, and I find it all fascinating.

Another example is the characters meaning “Japanese Language,” which are in the image posted above. In Japanese, the three characters are pronounced Ni Hon Go (Ni Hon meaning Japan and Go meaning language). In Korean, the same three characters mean the same thing but are pronounced Il Bon Eo (일본어 in Hangul). In Mandarin Chinese, the pronunciation is Ri Ben Yu. (Ni Hon/Il Bon/Ri Ben, by the way, literally means Origin of the Sun, which is why Japan is sometimes referred to as the Land of the Rising Sun.)

Unfortunately, my study of Japanese ended when I finished my MA. I immediately started law school after that, and there was no time to take extra classes. I did try to review both my Korean and Japanese during my law school years, but my new studies took priority.

Next up: How I (finally) came to study Chinese.

August 26, 2021

I’ve Got Questions for Jerry Mikorenda

Editor’s Note: This exchange is part of a series of brief interviews with emerging writers of recent or forthcoming books. If you enjoyed it, please visit other interviews in the I’ve Got Questions feature.

The Whaler’s Daughter by Jerry MikorendaWhat’s the title of your book? Fiction? Nonfiction? Poetry? Who is the publisher and what’s the publication date?

The Whaler’s Daughter by Jerry MikorendaWhat’s the title of your book? Fiction? Nonfiction? Poetry? Who is the publisher and what’s the publication date?The Whaler’s Daughter, fiction, Regal House Publishing (Fitzroy Books), July 24, 2021.

In a couple of sentences, what’s the book about?The novel takes place in 1910 on a whaling station in New South Wales, Australia, where twelve-year-old Savannah Dawson lives with her widowed father. The story is about unexpressed grief, and how friendship can turn revenge into repentance, anger to empathy, and hurt into hopefulness. In some ways, it’s a portrait of an artist as a young whaler.

What’s the book’s genre (for fiction and nonfiction) or primary style (for poetry)?It’s considered MG/YA historical fiction.

What’s the nicest thing anyone has said about the book so far?“The Whaler’s Daughter, ticks all the boxes: Twelve-year-old Savannah Dawson’s efforts to earn a place on her father’s whaling boat at the turn of the twentieth century in Australia will inspire twenty-first-century readers to hold fast in their quest to attain their dreams. A rollicking good story!” Karen Dionne, award-winning bestselling author of The Wicked Sister.

What book or books is yours comparable to or a cross between? [Is your book like Moby Dick or maybe it’s more like Frankenstein meets Peter Pan?]It’s about whaling so there has to be a tip of the cap to Melville. Comp-wise, as MG historical fiction, it would appeal to fans of older works such as The Evolution of Calpurnia Tate, West of the Moon, and Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy.

Why this book? Why now?Timing is always a peculiar thing with writing. Most of this book was originally developed eight years ago. And yet, the themes are still top of mind; gender roles, friendship, what does true equality mean? There’s a strong environmental message as well that will resonate with audiences. To reinforce those ideals, this fall through Bonfire we’ll be offering tee-shirts featuring the book cover with all the proceeds going the Center for Whale Research, Friday Harbor, WA.In the end, Whaler’s Daughter is about a group of young people who learned to listen and trust each other in order to accomplish something unique that few people knew about, but that was fine with them.

Other than writing this book, what’s the best job you’ve ever had?Working as a reporter on a small-town newspaper. There was no money in it and few of those papers still exist today, but it was as fun as it was frustrating. You covered the goofy, the poignant, the tragic, the pompous, the bitterness of life, and sadness of small towns. It was a great experience for a writer.

What do you want readers to take away from the book?As with most books for young folks, a sense of hopefulness. Along with an awareness that the decisions they make when they’re young will contribute to who they’ll be when they grow up. Life is sad, happy, and tragic, but it’s your life so live it as you see fit, not the way others want you to.

What food and/or music do you associate with the book?Ha! Let’s see, bushman’s stew, tommy sauce, pie floaters, skipjack, Sunny Jim flakes, damper bread, mutton stew. As for songs, The Dying Stockman, The Female Rambling Sailor, Click go the Shears, and the Blue Bells of Scotland were all in the book. The Wellerman sea shanty was hugely popular on Tik Tok last summer. I could see the Dawson crew singing that as they rowed out to work.

What book(s) are you reading currently?On the recently read, reading, want to read list, in no particular order: Sand Talk, Tyson Yunkaporta, Edge of the Empire, Bronwen Riley, Manhattan Beach, Jennifer Egan, The Wicked Sister, Karen Dionne, CRISPR, Yolanda Ridge, So Many Ways to Lose, Devin Gordon.

Jerry Mikorenda

Jerry MikorendaLearn more about Jerry on his website.

Follow him on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook

Buy the book from the Publisher (Regal House/Fitzroy Books), Amazon, or Bookshop.org

August 25, 2021

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Part 3

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Learning Chinese Characters in Korea

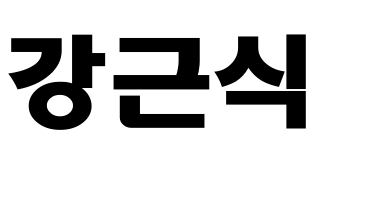

One of the first things I needed to learn in Korean was my name. In our Peace Corps training, the language teachers assigned us names that usually had some connection to our American names. The surname my teacher gave me was Kang, which has an obvious connection with my actual surname, Garstang (especially when you know that the letter K in Korean is a sound somewhere between a G and K). In Korea, as in China, the surname comes first, and my teacher completed my name with two syllables, Kun-shik. (I don’t think this is a particularly common combination, but I’ve Googled it and there are other people who have this two-syllable given name also.)

In Hangul, the Korean alphabet, my name, Kang Kun-shik, is written 강근식. These sounds are derived from Chinese characters, however, so for some purposes the Chinese would be used. In Chinese characters, Kang Kun-shik is written 康根植 (see the image above). The pronunciation of these characters in Mandarin Chinese is a little different, but I’ll come back to that in a future post. Note that each of the characters has a meaning, although the meaning of the given name is more important than the surname, which is merely passed down in the family, and there are relatively few surnames in Korea. For what it’s worth, Kang means healthy. Kun-shik means to take root, or the root of a plant. I’ve always liked the name and its meaning.

Anyway, these were the first words I learned to write in both Korean and Chinese. As I continued to study Korean, I needed to learn many more Chinese characters. The name of the University where I taught was usually written in Chinese characters, as was the name of the city where I lived. Many stores and restaurants had names written in Chinese. And so on. It was simply a part of learning Korean. It wasn’t necessary for speaking, which was the most important thing, but for reading it was needed.

I think many of my Peace Corps colleagues struggled with the Chinese characters, content to master the Korean writing system, but one of the best things I did in my first year in the country was to study calligraphy with a master teacher in my city. We were encouraged by the Peace Corps to engage in some kind of cultural activity, and because I was already intrigued by the writing systems, that’s what I chose. While some of the Korean students in this calligraphy master’s studio were learning to write in beautiful Hangul script, I chose to learn Chinese character calligraphy. (This is far more involved than it sounds and is nearly meditative in its process: one first spends a great deal of time rubbing ink in a bit of water on a specially carved stone until it is the perfect consistency; then one practices holding the brush just so; then comes the exercise of tracing the beautifully drawn characters one is learning.) The reason this was beneficial in the long run is that characters must be drawn in a particular shape, with strokes done in a specified sequence, and learning the proper sequence aids in memorizing and reproducing the characters. The repetition of painting the characters with a brush drilled that sequence into me.

Because I found this all so interesting, I also invested in flashcards of the characters used in Korean so I could begin to learn them. Along with the dictionaries I picked up back then and various other language-learning books, I still have those flashcards.

Next, I’ll write a bit about how my study of Korean morphed into a study of Japanese.

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Part 2

My Mandarin Chinese Journey: Korean

So, how did I start to study Chinese? The answer is a little convoluted.

After college, I joined the Peace Corps. In those days, they asked you what languages you spoke as a way of helping them determine where to send you. I’d studied German for several years and I’d taken some Russian in college, but at the time neither language was spoken widely in any Peace Corps country. (That would change in the 1990s when the Peace Corps began sending volunteers to newly independent countries of the former Soviet Union, where Russian would come in handy.) Given that there were lots of volunteers who had studied French and Spanish, the languages used in parts of Africa and South America where the Peace Corps was active, I suspected I’d be sent to Asia, to some place like Thailand, where everyone would be on an equal footing and have to learn the language from the beginning.

I was close. The Peace Corps sent me to South Korea, a country about which I knew very little. I had never eaten Korean food. To my knowledge, I had never met a Korean person. And I don’t think I had ever heard Korean spoken or seen the language written. My first exposure to the language, then, was when my group of volunteers gathered in San Francisco for a “staging,” the last step before boarding a flight for our service country. In a hotel conference room, we gathered for some very basic instruction in Korean, probably nothing more than “hello” and “thank you” (both of which sound pretty complicated if you’ve never heard them before). We all went out to a meal at a Korean restaurant—my first bulgogi and kimchi! And after a couple of days of medical exams, shots, teambuilding exercises, and orientation sessions, off we went to Asia. After an overnight stop in Tokyo, we arrived in Seoul.

At that time, English was not widely spoken in Korea, even though there were over 40,000 American soldiers stationed in the country. In fact, my group was there in order to help improve English education by teaching English to future English teachers, but in the meantime, we needed to learn at least some Korean just to survive. After a couple of days in Seoul—familiarization, learning about bathhouses, more orientation sessions, etc.—we were tasked with buying bus tickets on our own and making our way to the small provincial city where our real training would take place. That experience drove home the need to get a handle on the language, and quick.

Having arrived safely in the city of Cheongju, our training began. It consisted of a morning of language classes and an afternoon of other activities, including classes in Korean culture and history as well as guidance in Teaching English as a Second Language, which eventually also involved practicing our teaching skills with Korean students. For me, though, the most enjoyable part of the training was the time we spent in our language classes.

What, you may be wondering, does any of this have to do with Chinese?

I was surprised to learn two things about Korean. First, the language is written using a phonetic alphabet, Hangul, that was invented by Korean scholars in the 15th Century. Until then, the language was written using Chinese characters, and in fact Korean elites continued to use Chinese characters for another 500 years. When I arrived in the country, Koreans still needed to know about 2,000 Chinese characters in order to read the newspaper, but this is, apparently, no longer the case as the use of those characters has dwindled.

Still, Chinese characters are useful in Korea. Most people have names that originate from Chinese characters. Most place names are written in Chinese. And there are many loan words from Chinese, the Korean pronunciation of which is usually close to an earlier Chinese pronunciation of the same word.

So, as I began to learn Korean, I was also beginning to learn Chinese characters.

More about that in the next installment.