Clifford Garstang's Blog, page 103

May 21, 2012

The New Yorker: "Referential" by Lorrie Moore

May 28, 2012: “Referential” by Lorrie Moore

If it weren’t for the Q&A with Lorrie Moore I would not have known that this story by Lorrie Moore is derivative (Moore uses the word “homage”) of “Signs and Symbols” by Vladimir Nabokov, a story published in the magazine in 1948. Although that story is a starting point, Moore seems to be going somewhere else with it, although I can’t say that for sure having not read the original. (This story is behind the paywall.)

Moore’s story is about a widow whose teenage son is institutionalized because he is a danger to himself, and has been for a long time. It isn’t always clear why kids are like that, and it’s not clear in this case, although his father died when he was young. For the past several years, the mother has been in a relationship with Peter, who is something of a step-father to the boy, but the boy’s deepening trouble appears to have been too much for Peter to handle and he’s been pulling away. In this story, the separation is nearly complete. And yet the mother wants to bring the boy home—an act, it seems to me, that could have only one result. And maybe that’s what she really wants.

The story is short and readable, but not, for me, as good as many other Moore stories I’ve read. If anyone has read the Nabokov, I’d love to hear comments about it.

The New Yorker: "Referential" by Lorrie Moore

May 28, 2012: “Referential” by Lorrie Moore

If it weren’t for the Q&A with Lorrie Moore I would not have known that this story by Lorrie Moore is derivative (Moore uses the word “homage”) of “Signs and Symbols” by Vladimir Nabokov, a story published in the magazine in 1948. Although that story is a starting point, Moore seems to be going somewhere else with it, although I can’t say that for sure having not read the original. (This story is behind the paywall.)

Moore’s story is about a widow whose teenage son is institutionalized because he is a danger to himself, and has been for a long time. It isn’t always clear why kids are like that, and it’s not clear in this case, although his father died when he was young. For the past several years, the mother has been in a relationship with Peter, who is something of a step-father to the boy, but the boy’s deepening trouble appears to have been too much for Peter to handle and he’s been pulling away. In this story, the separation is nearly complete. And yet the mother wants to bring the boy home—an act, it seems to me, that could have only one result. And maybe that’s what she really wants.

The story is short and readable, but not, for me, as good as many other Moore stories I’ve read. If anyone has read the Nabokov, I’d love to hear comments about it.

May 15, 2012

Short Story Month: "Cousin Barnaby is Dead" in Joyland

Usually, I'm all over Short Story Month. Not this year, though, and I'm sorry about that. I've got a book coming out in the fall and I'm revising another book that will soon be shopped around to publishers (I hope), and I've been too busy.

Usually, I'm all over Short Story Month. Not this year, though, and I'm sorry about that. I've got a book coming out in the fall and I'm revising another book that will soon be shopped around to publishers (I hope), and I've been too busy.But, a story of mine just appeared in a cool online magazine, Joyland . So that will have to be my contribution to the celebrations of short fiction: Cousin Barnaby is Dead. I hope you like it.

May 14, 2012

The New Yorker: "The Proxy Marriage" by Maile Meloy

May 21, 2012: “The Proxy Marriage” by Maile Meloy

I loved this story, except for the beginning and the ending. Regarding the ending, I suppose I shouldn’t stay too much, although (a) the story is online for free and I urge everyone to read it and (b) there is something of a spoiler in the Q&A with Maile Meloy. While I am not opposed to happy endings in general, when they are overly sentimental (sealed with a kiss!), they spoil the whole reading experience for me.

As for the beginning, I had just finished explaining to a student why she needed to reconsider the overabundance of the verb “to be” in her story. And by “just” I mean immediately before I read “The Proxy Marriage.” Count ’em. In the first paragraph, containing five sentences, “to be” is used six times. Ugh. Kids, don’t try this at hime.

So, none too promising, the beginning leads into a nice story about William and Bridey, high school pals. He loves her (but is shy), she’s oblivious. At some point they begin to serve as proxies for weddings, a strange thing that Montana law apparently allows. It kills William. Bridey still doesn’t get it. They go off to college and live their lives, occasionally coming back and doing more weddings. Until finally one of the couples is present by Skype and wants the wedding sealed with a proxy kiss. William kisses Bridey, instant chemistry, and their lives are changed forever.

There’s some great dialogue and William especially feels real. (I loved it when he goes from college in Ohio to graduate school in Indiana and his girlfriend at the time berates him: “You’re tired of Ohio, so you’re going to Indiana?” she says.)

So. It’s a nice story. She lost me with the ending.

May 11, 2012

New Update for Prime Number

The latest update of Prime Number Magazine has gone live! 19.2 features flash fiction by Brian Conlon, Robert Kaye, and John Duncan Talbird, a short essay by Alice Lowe, and poetry by Michael Kriesel, and Ira Sukrungruang.

The latest update of Prime Number Magazine has gone live! 19.2 features flash fiction by Brian Conlon, Robert Kaye, and John Duncan Talbird, a short essay by Alice Lowe, and poetry by Michael Kriesel, and Ira Sukrungruang.Please take a look! The magazine is always looking for good work, so please submit.

May 7, 2012

The New Yorker: "Sweet Dreams" by Peter Stamm

May 14, 2012: “Sweet Dreams” by Peter Stamm

It’s a little difficult to discuss this story, which is translated from the German, without revealing its ending, although the author does in the Q&A with Peter Stamm, which I recommend that you wait to read until after you’ve read the story. Likewise, don’t read this discussion until you’ve read the story (which, unfortunately, is behind the pay wall).

Lara and Simon are a young couple living together in a Swiss village. Lara is somewhat unsure of herself, and wonders if her relationship with Simon will last. Simon declares his love, but also seems unsure. On their way home from the city where they work, Lara sees a man on the bus who looks familiar. Later, in the restaurant below their flat, she catches a glimpse of the man on television. Lara and Peter get a little drunk and make love, twice, on the floor of their Ikea-furnished apartment. Peter goes to bed, but Lara gets up and watches television, where she sees the man again.

All very conventional, but not very interesting. What’s interesting is that the conversation on the talk show, between the host and a writer, is about an idea he’s had for a story after seeing a young couple on the bus. The suggestion, at the end, is that Lara and Simon are the characters he has invented.

This twist at the end is fun, but personally I felt the story should have prepared us for the possibility that the characters are just characters. Still, the open-endedness of the young couple's lives, the sense that anything could happen--not only because they have their lives ahead of them but also because the writer has not yet written their story--is appealing.

May 5, 2012

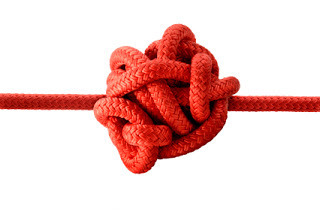

Tips for Writers: Which vs. That

Let’s try to untangle a knot that some writers find themselves in: how to know when to use “which” and when to use “that.” The question arises today because of a story I’m editing.

The story, which consists mostly of one wonderfully long sentence, necessarily contains a lot of relative clauses in order to get from beginning to end. Both “which” and “that” are relative pronouns, so it’s no surprise that both appear frequently in this piece.

Using “which” when “that” is called for is a common error, but grasping the difference isn’t that hard.

Take a look at Chicago Manual of Style 5.202 (I’m using CMOS 15) on Word Usage:

That; which. These are both relative pronouns. In polished American prose, that is used restrictively to narrow a category or identify a particular item being talked about; which is used nonrestrictively—not to narrow a class or identify a particular item but to add something about an item already identified. Which should be used restrictively only when it is preceded by a preposition. Otherwise it is almost always preceded by a comma, a parenthesis, or a dash. In British English, writers and editors seldom observe the distinction between the words.

This is reasonably clear, I think. But Bryan Garner in Garner’s Modern American Usage, explains further.

The simplest statement of [the rule] is this: if you see a whichwithout a comma (or preposition) before it, nine times out of ten it needs to be a that. The one other time, it needs a comma. Your choice, then, is between comma-which and that. Use that whenever you can. . . A restrictive clause [using that] is essential to the grammatical and logical completeness of a sentence. A nonrestrictive clause [using which], by contrast, is so loosely connected with the essential meaning of the sentence that it could be omitted without changing the meaning.

May 3, 2012

5/3: It’s National Press 53 Day!

Today, May 3, is National Press 53 Day. (5/3 — get it?). I love Press 53, publisher of my 2009 linked story collection In an Uncharted Country as well as my forthcoming novel in stories, What the Zhang Boys Know.

It’s a great small press that specializes in short story collections and poetry.

Help me celebrate! There are lots of ways. If you already have my book, take a picture of it and post it on Facebook. (Seriously!) If you don’t yet own my book, please consider buying it from Amazon, your local Independent Bookseller, or directly from Press 53. (You can even order it from me at CliffordGarstang.com, which will get you an autographed copy.) And while we’re celebrating, visit Press 53 and see all the great books they’ve published.

5/3: It's National Press 53 Day!

Today, May 3, is National Press 53 Day. (5/3 -- get it?). I love Press 53, publisher of my 2009 linked story collection In an Uncharted Country as well as my forthcoming novel in stories, What the Zhang Boys Know.

Today, May 3, is National Press 53 Day. (5/3 -- get it?). I love Press 53, publisher of my 2009 linked story collection In an Uncharted Country as well as my forthcoming novel in stories, What the Zhang Boys Know.It's a great small press that specializes in short story collections and poetry.

Help me celebrate! There are lots of ways. If you already have my book, take a picture of it and post it on Facebook. (Seriously!) If you don't yet own my book, please consider buying it from Amazon, your local Independent Bookseller, or directly from Press 53. (You can even order it from me at CliffordGarstang.com, which will get you an autographed copy.) And while we're celebrating, visit Press 53 and see all the great books they've published.

April 30, 2012

The New Yorker: "Nero" by Louise Erdrich

May 7, 2012: “Nero” by Louise Erdrich

See the Q&A with Louise Erdrich.

What have we got here? A mean dog who likes gingersnaps and lives to escape, whose will to live is defeated when the possibility of escape is removed. You have to feel sorry for the dog, as the story’s narrator seems to, in a dispassionate, cool sort of way.

And then you’ve got a neighbor who likes to beat up on suitors to his daughter, until the narrator’s uncle nearly kills him, and then his tune changes. The fight between the uncle and the neighbor is entirely predictable, and I kept hoping for a tornado or some other calamity to come and wipe out the town before we had to deal with it was obviously coming. (In fact, the outcome was so much expected that I was sure it couldn't turn out that way, so that when it DID turn out that way, it was almost a surprise.)

Seriously, the only thing interesting here was Nero, the dog, and what happened to him was tragic. Oh, the chaos at the school with the escaped snake and the tarantula was amusing. And because these animals come in cages but find themselves temporarily loose, which is what happens to Nero the dog and also the uncle’s girlfriend, presumably we’re supposed to see some theme about the tragedy of constraint. Maybe.

Erdrich is sometimes enjoyable to read, for me. This isn’t one of those times.