David A. Powell's Blog, page 9

January 11, 2016

For your listening pleasure…

Time for a musical interlude:

From time to time, I discover a musical connection to Chickamauga. I stumbled across the band “Larkin Poe” a while back, for example, and noted their connection to the battle.

And “Uncle Tupelo” had a song titled “Chickamauga” on their 1993 Album Anodyne. Uncle Tupelo has long since broken up, but the song lives on in occasional performances by subsequent bands, Son Volt and Wilco.

But Jimmy Driftwood?

New to me, if not to the world. Check it out.

January 5, 2016

Glory or the Grave makes the History Book Club

I have been reliably informed that Glory or the Grave, Volume II of The Chickamauga Campaign, is the January 2016 selection of the History Book Club.

http://www.historybookclub.com/the-chickamauga-campaign-glory-or-the-grave.html

Thank you, HBC, and the good folks at Savas-Beatie. This is very cool.

December 26, 2015

More Angry Generals

Daniel Harvey Hill did not shine at Chickamauga. To many students of the Civil War, Hill is famous for three things: South Mountain, annoying Robert E. Lee, and authoring a marvelously unreconstructed mathematics textbook after the war. Some think that D. H. Hill received short shrift from Lee, and that Daniel Harvey might have made a better corps commander than either Richard Ewell or Ambrose Powell Hill (D. H.’s cousin) had D. H. been promoted instead of banished from the Army of Northern Virginia.

I am less sanguine about that. . .

From Glory or the Grave:

Lieutenant General Daniel Harvey Hill was not having one of his better days. While his men were turning George Thomas’s flank, Hill was focused on a different conflict, locked in a battle of wills with almost every other commander in the Confederate Right Wing. At the moment his primary adversary seemed to be Maj. Gen. William H. T. “Shotpouch” Walker.

What followed could have been a farce written by Gilbert and Sullivan if it were not for the soldiers’ lives being thrown away in the meanwhile. “General Hill informed me . . . that he wanted a brigade,” Walker reported. This should not have been a problem: “I told him that there was one immediately behind him.” In response, Hill “remarked that he wanted Gist’s brigade.” Walker explained that Gist’s men were at the rear of his column, just catching up, and would take the longest to go into action. No matter, Hill was adamant. Gist was present for this exchange, having just reported to Walker and been informed that he was going to command Ector and Wilson as well as his own formation. The South Carolinian was flattered, noting that Hill insisted on “Gist . . . saying he had heard of that brigade.”

Throughout this exchange Polk remained mute. Not so the irascible Walker, who was growing increasingly irate and not shy about expressing that anger. Various subordinates and staff officers watched in alarm. Walker’s other divisional commander, St John Liddell, was also present and no doubt recalled Walker’s similar diatribe against General Polk on September 13th. Walker, noted Liddell, “severely criticized and loudly found fault with the propriety of Hill’s plans . . .” Eventually, they hammered out an arrangement of sorts: Colquitt would go in to support Breckinridge’s attack, coming up on what was thought to be Breckinridge’s left rear, in place of Helm. Gist would move Ector and Wilson up to support Colquitt.

This was the Army of Tennessee at its worst. Walker wanted to concentrate his command and use it en masse¸ while Hill and Polk seemed intent on trickling troops into the fight one brigade at a time. Hill was also being mulishly obdurate. Despite being granted almost complete control of the whole attack by Polk, Hill would later complain bitterly about how the assault was conducted, almost as if he were a spectator rather than the tactical commander. In his report Hill ranted at how useless the whole fight had been, railing at “the faultiness of our plan of attack,” and waxed hyperbolic when he complained that “never in the history of war had an attack been made in a single line without reserves or a supporting force;” all the more unfortunate because it was against a fortified enemy.

Two decades later, writing for Century Magazine, Hill still described the attack as a “desperate, forlorn hope.” Here he further lamented about faulty reconnaissance, suggesting that if only time had been taken to better understand the Union position, the morning’s bloody frontal assaults need not have been conducted. Of course, it was Hill who made that reconnaissance, Hill who determined the alignment of his two divisions, Hill who failed to grasp the extent of Breckinridge’s success, Hill who could have called on Walker’s entire corps as support, and Hill who initially refused most of that corps when it was offered to him.

Few if any officers in military annals have ever complained about receiving too many reinforcements!

December 8, 2015

Update on the Study Group

Currently, reservations for the study group are at 14 – plus three for cadre (Jim Ogden and myself, basically) and the park. This is a fine start, about equal to last year, and we had a pretty full bus last March.

So to make sure you have a seat, please reserve your space now!

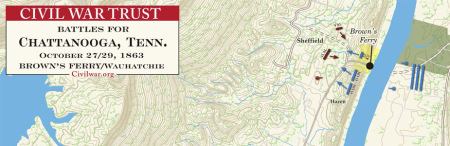

Last year, we had such a strong response that we were able to donate $900 to the Civil War Trust, which went towards land acquisition at Brown’s Ferry and around Dalton Georgia. (see map, above – we contributed to that yellow patch.) Even better, we did so at about a 4 to 1 match.

Here’s the link to the details

December 6, 2015

Angry Generals

I time for a short excerpt:

Early on the morning of Sunday September 20, somewhere near smoldering remains of the Alexander cabin, Captain J. Frank Wheless found himself caught in the middle of what would be one of the most significant controversies of the war: The three-way train wreck of miscommunication between Confederate Generals Braxton Bragg, Leonidas Polk, and Daniel Harvey Hill.

Frank Wheless was a 24-year old from Clarksville, a combat veteran of the 1st Tennessee Infantry, now serving on Polk’s staff. When at dawn, Polk awoke and waited for the expected roar of D. H. Hill’s attack, he was greeted only by silence. Discovering that the previous night’s orders were never delivered, Polk immediately dispatched Wheless with replacement instructions.

Wheless soon found Hill, in company with both divisional commanders Patrick Cleburne and John C. Breckinridge. Wheless attempted to deliver his orders (made out to Cleburne and Breckinridge, because Polk thought Hill was missing.) Hill intercepted them. The captain would get no satisfaction from Hill, only an argument that an immediate attack was impossible now, the men had to eat.

The frustrated staffer rode away. He soon met his boss, Polk, along the Alexander Bridge Road.

[the following is excerpted from Glory or the Grave,]

“Wheless dutifully explained his discussion with Hill, doing little to hide his irritation with the North Carolinian. “General,” he burst out, “you notice General Hill says it will be an hour or so before he is ready to make the attack. I am confident that it will be more than two hours before he is ready.” This statement was recorded in an official declaration Wheless drafted just ten days after the battle. Polk “asked, with surprise, why I thought so. I answered, ‘General Hill seems to me perfectly indifferent.’ General Polk responded quickly and with decision. ‘Well, Sir. Well Sir. I must go and see to this myself.’” After Polk dictated a quick note to Bragg outlining Hill’s reasons for delay, the Bishop ordered Wheless to stay put, establishing Right Wing headquarters on the spot, and rode off to find Hill.”

“Not fifteen minutes later, Bragg rode up and demanded Polk’s whereabouts. Wheless explained all that had passed, outlining the previous night’s confusion. He also emphasized Hill’s delays, eager to deflect Bragg’s obvious anger away from Polk and toward Hill. Bragg wasn’t swayed. When Wheless repeated his story of the two-hour delay to the army commander, Bragg sarcastically inquired “how [Wheless] expected General Hill to make the attack before he received orders to do so.” Flustered, Wheless only made things worse by pointing out that when he (Wheless) left Bragg the night before he was under the impression that Bragg had going to issue orders to Hill in person, outlining the plans for the 20th. Polk’s orders, averred the captain, were only confirming instructions that were supposed to have been already given “so that there could not possibly be any mistake.”

“Wheless’s not-quite-so-subtle effort to shift blame away from the bishop and this time onto Bragg himself only deepened the army commander’s anger toward Polk and, by extension, Wheless. Sensing his blunder, Polk’s staff officer quickly changed tack, steering matters back to the subject of Hill’s recalcitrance. Here he stumbled again, however, by adding in the detail of Cleburne’s remark about the Federals felling trees. “‘Well sir, is this not another important reason why the attack should be made at once?’” snapped the incensed army commander. Wheless agreed; but, he rejoined, “‘it did not seem to impress General Hill in that way.’”

“Without another word Bragg rode on to find Polk and/or Hill, leaving the discomfited Wheless in his wake. By 7:30 a.m., the Confederate right was buzzing with angry generals, each surrounded by a sub-swarm of agitated staff officers. Despite the hive of activity and authority no attack was forthcoming.”

Wheless would later write out a sworn statement supporting his boss, Polk, as part of the defense Polk assembled for what all expected would be the court-martial of the century, at least as far as the Army of Tennessee was concerned. Polk, of course, never sat before such a court – President Davis talked Bragg out of holding a public spectacle and instead arranged for Polk to be transferred to Mississippi.

When I first wrote this passage, I wondered what was going through Wheless’s mind as he found himself in the middle of the maelstrom. His loyalty to Polk is obvious in his statement, as his his animosity towards Hill; but was he cowed by Bragg’s obvious short-tempered displeasure?

Apparently not. Instead, after Polk’s departure, Bragg offered Wheless a job on his own staff, as an assistant inspector-general. He was sent to Giffin, Georgia. In February, 1864, Frank Wheless resigned his commission, claiming disability for further field service, and instead entered the Confederate Navy as a paymaster, serving in North Carolina. Near the end of the war Wheless was transferred again, to the James River Squadron, where he was re-united with Bragg – once again, Bragg offered him an army commission as a Lieutenant Colonel, IG Branch.

Wheless refused that commission. The end of the war was apparent, and he saw no point in changing services a second time. At the end, Wheless helped evacuate the Confederate Treasury from Richmond, accompanying it, along with Davis and the rest of the fleeing Confederate Government, as far as Abbeville South Carolina. There he helped disburse the last of the funds to Davis’s cavalry escort, and having done all he could, left the service of the rapidly disintegrating Confederacy.

Frank Wheless died on August 10, 1891, at the age of only 52.

And I still wonder how often, in later years, his thoughts went back to that critical morning, when for a little while, the fate of the Confederacy seemed to be in his hands.

October 6, 2015

2016 CCNMP Study Group: March 11-12th.

It’s time to post information about the March 2016 Study Group tour. See below:

CCNMP Study Group 2016 Seminar in the Woods.

Mission Statement: The purpose of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park Study Group is to create a forum to bring students of the American Civil War together to study and explore those events in the fall of 1863 that led ultimately to the creation of the Chickamauga & Chattanooga National Military Park.

Tour Leaders: Jim Ogden and Dave Powell

Date: Friday, March 11, and Saturday, March 12, 2016; By bus and car caravan.

All tours begin and end at the Visitor’s Center.

By Bus:

Fri day, 8:30 a.m. to 5:00: Feint, Deception and Maneuver: Union Operations north of Chattanooga.

Note: Since we cannot guarantee that Resaca Battlefield will be open in March 2016 (still) we have decided to explore other aspects of the campaign for Chattanooga.

On Friday we will visit historical sites associated with Wagner, Hazen, Minty and Wilder’s operations north of Chattanooga, prior to the battle of Chickamauga.

NEW! Friday evening, 7:30 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. – site TBA – Q&A Panel with Jim Ogden, Dave Powell, and Emerging Civil War Author Lee White. (possibly others)

Car Caravan – Saturday Morning, 8:30 to Noon: Van Cleve enters the fight.

We will explore Van Cleve’s Union division, and the September 19th fighting in the woods between Brock and Brotherton Fields.

.

Car Caravan – Saturday Afternoon, 1:30 p.m. to 5:00 p.m.: Breckinridge attacks!

We will explore John C. Breckinridge’s September 20th attack that turned Thomas’s flank and penetrated to Kelly Field.

Cost: Friday’s Tours will be by Bus. Pre-registration Fee: $45 Due by February 1st, On-site Sign up Fee: $50

Send to (and make checks payable to):

Dave Powell

522 Cheyenne Drive

Lake In The Hills IL 60156

Please also note that this fee is NON-REFUNDABLE after February 1st, 2015. Once we are committed to the bus, we will be charged the booking fee.

September 21, 2015

September 21, 1863. “Bragg . . . was cheered long and hard.”

Chickamauga sparked a rare moment of celebration within the Army of Tennessee. Never before had Bragg’s army gained such a clear-cut, unequivocal triumph.

From the Diary of Surgeon Ropert P. Myers, 16th Georgia:

Sept 21, 1863. (Chattanooga)

Genl Bragg rode down the lines today, and was cheered long and hard. He had no uniform on, simply a loose blouse. He rode a beautiful bay horse, his staff and escort very large – quite different from the Genls of the Army of Northern Virginia, Genl Lee and all his Lieuts & Majors were accompanied with a small staff and escort.

When Bragg reached the vicinity of Kelly Field, he encountered Major General John C. Breckinridge. For once, personal enmity was set aside.

From the letters of E. John Ellis, 16th & 25th Louisiana, Adams’s Brigade, Breckinridge’s Division:

Field before Chattanooga, Oct 4th, 1863

My Dear Brother,

[On Monday September 21st] Bragg rode along the lines where all of the troops were Bivouacked amidst the wildest enthusiasm of his victorious army. As he passed our brigade I noticed Gen. Breckinridge down among the men, with his hat off, whooping as lustily as any private. I am glad they have buried the hatchet. Breckinridge though not much of a military man is the impersonation of all that is gallant, chivalrous & generous; while Bragg is truly a great man.

September 20, 2015

September 20, 1863.

The combat of the 19th proved inconclusive. Not so that of the 20th. Confederates under John C. Breckinridge came near success early on Sunday when they turned George Thomas’s left, but were repulsed. Their success, however, only strengthened Thomas’s concern for his northern flank, and redoubled calls for reinforcements. By 11 a.m, the Union right was dangerously weakened in order to meet those calls. James Longstreet’s attack against the newly-vacated line in Brotherton Field quickly overwhelmed those few defenders – the men of Jefferson C. Davis’s small division – quickly. Then Hindman’s troops assailed Horseshoe Ridge.

Four days later, Private Joel H. Puckett of the 24th Alabama recounted that morning’s experiences to his wife:

Camp near Chattanooga, Sept 24, 1863

Dear Mollie,

Sunday morning we charged his breastworks and drove him about a mile. Our reg was engaged from nine to twelve A.M. [p.m.] Here we sustained a heavy loss in our company. Mollie here at one time I bid you goodbye for ever. Loften was killed in the first charge. We captured a great many waggons, 8 pieces of artillery, lots or Ordinance, small arms canteens etc.

We rested until 3 p.m. Our company was thrown out as skirmishers and when we found him [the Federals] he was on a Vicksburg hill in mass. Our reg charged that hill three times. Many a brave man fell, but we piled that ground with Yankee slain. Our division was fighting McCooks Corpse and we still had that hill to take inch by inch.

I saw many wounded by my side, and thank God we slept that night on the battlefield, and the Yankees never stopped till they reached Chattanooga. I took one prisoner by myself and help to take others. [G]ot me a pair of blue pants, a splendid pr of boots, 3 rings shell [?] an gutta percha [gum blanket] a fine tooth comb and 80 dols in green back, also 2 zinc canteens.

A. Loften was shot in the head. Pate in arm – amputated. Clordy knee – leg amputated. Hooper – head. Moor – hand. Archibald – shoulder and foot. Leonard – arm amputated. These were the worst wounded. Our reg lost 114 killed and wounded. The enemy’s loss was immense. I only speak of the battle where I saw it. The rest of us are all well.

J. H. Puckett.

September 19, 2015

September 19, 1863. “Center Shot.”

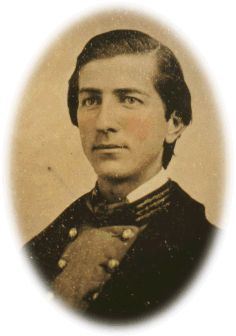

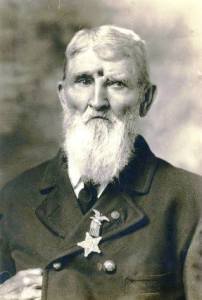

You may have seen this picture before, as it has been posted elsewhere from time to time. The full story behind it is remarkable.

This striking image is of Union Private Jacob Miller, Company K, 9th Indiana Infantry. Miller went into action with the rest of his regiment about 1:00 p.m., in Brock Field. the 9th belonged to Hazen’s Brigade, of Palmer’s Division, the 21st Corps; they fought men from two brigades of Tennesseans from Frank Cheatham’s division, Polk’s Corps. Miller’s account departs from my previous practice in this series, in that his story is a post-war reminiscence, not something written closer to the event. However, his story is so striking – alarming, upsetting, and inspiring – that I feel it belongs here. I have excerpted some material.

The History of My Wound, by Jacob Miller.

While on the firing line hear the Brock Cabin at the battle of Chickamauga, while lying down to take aim at an enemy, some Johnny Reble got careless with his old musket and accidentally or otherwise pulled the trigger while the muzzle was pointed my way. I stopped the full charge of lead, consisting of one round ball and three buckshot, between the eyes, passing to the left under the frontal bone crushing my left eye out of the cavity well. I thought I was done for.

My Captain told me . . . that when I was hit I lay on my face a short time before I got to my feet with the blood streaming from the wound. The captain asked me if someone should take me to the rear [but] I said no.

Thus I started back carrying my gun. Of course I did not realize anything for some time after that. [Here Miller must have fallen or lain down.] At last I became conscious and raised up in a sitting position. Then I began to feel for my wound. I found my left eye out of its place and tryed to place it back but I had to move the crushed bone back as near together as I could first. Then I got the eye in its proper place. I then bandaged the eye as best I could with my bandana. I could hear the firing not far away, some of the bullets even striking hear where i was sitting.

When I got to my feet to find out where I was, I could see no one. I did not know which way to go or what to do, so I poured some water out of my canteen on the bandage. Then I sat down against a tree with the idea that someone would come past me and would know how to act or what to do.

[Here Miller recounts meeting a wounded Confederate, giving him water, and having him point out the direction of the Union rear.]

Then I got my gun and hastened in the direction he pointed out through the thick woods that came to a point where the firing was off to the side. I advanced cautiously and had not gone far when I heard a noise behind me, which proved to be some of the enemy coming up to form the line. Just at that point I heard the command given to halt and lie down. I was making myself as scarce as possible but it was slow work as my good eye was getting almost closed.

I was picking my way the best I could among the trees and underbrush to get back from the fierce conflict, trying to find a road. After struggling for a while I came out on a byroad, wending among the trees. I was very glad as my head was swollen so badly that my good eye was at times closed with the blood running into it and clotting there. As I had but little water in my canteen, I had to use it to wet my parched lips and throat.

While I went along the road I heard a horse coming toward me and when I was close enough for me to see who the rider was, I discovered it to be my first captain, [now] Major William P. LaSelle. He halted as I called his name and saluted, and [he] asked who I was. I replied that I was Miller number three of Co. K. He ordered me to drop my gun and everything but my canteen and grub sack and get on his horse. He said he would take me to the field hospital. I obeyed his order, all but letting him take me back. I urged him to hasten to the regiment but not to go in the direction from which I had come, as there were some of the enemy there, and none of our troops. He rode away from me and I learned later that he went straight into the Johnnys and was captured.

[Miller apparently did not let the major take him to the rear, for he goes on to recount more struggles on his own, an encounter with some men of the 4th Michigan cavalry, collapsing in pain and exhaustion, before being retrieved by two stretcher bearers, who finally carried him to the divisional hospital. There, however, he received grim news.]

When it came my turn I was examined by the surgeons. They discovered that the wound was mortal and that I would die soon, and that it was foolish to do anything with it. But they bandaged it with wet bandages and I was laid in a tent. . . .At last I became unconscious. That was a mercy to me after what I had passed through. . . . Next morning I came out of my swoon, or whatever you might call it. I wet the bandage and had a good draught. I found the swelling had diminished in my eye and that I could see a little. After a time a surgeon and a scribe came into the tent and when they got to me, the doctor was surprised to see that I was still alive.

[This was September 20th, and the hospitals were being evacuated, except for those men too badly wounded to be moved. The Confederates were approaching, and the men left behind would soon all be prisoners. Miller determined otherwise.]

After he had gone from the tent I went to the spring, filled my canteen, wet my head and washed as much of the blood off my face as I could, because I had made up my mind that I would not be taken a prisoner as long as I had strength to make a step toward Chattanooga. I would rather die trying to get there than to be captured.

MIller managed to make his way back to Chattanooga, partly walking, and then riding in an ambulance, by Monday September 21. There his wound was re-dressed. Over the next week, Miller journeyed to Bridgeport, where he was placed on a train. At Nashville he was finally bathed, his would cleaned, and dressed again. His next stop was Louisville, and then the large Union hospital complex at New Albany Indiana, just across the Ohio River – into “God’s country,” as Miller told it.

Miller recovered sufficiently to move from patient to semi-invalid hospital attendant. In the Spring of 1864, he was in Madison Indiana, working in wards numbers 3 and 6. He secured a 30 day furlough in June, and went home to Logansport. He still carried the musket balls in his forehead.

I went to Dr. J. M. Fitch’s office, to [see] his partner, A. C. A. Colman. I told him what the doctors in the different hospitals had said about an operation on my wound. I told them if they would do the operation I would risk the dying part of it. They put me in a barber’s chair and probed for the lead, found it, and got hold of it with forsips. They pulled it to where it had gone in but the frontal bone had knit to the skull bone where I had placed it, so the ball was bigger than the hole, thus it could not come out.

Miller was discharged in August of 1864, with his comrades in the 9th, at the expiration of their enlistment. He returned home, but would suffer the effects of his wound the rest of his life.

Seventeen years after I was wounded I was washing the pus off my face one morning when something hard dropped into the pan. When I took it out I found it to be a buckshot. Thirty-one years after being wounded two more buckshot fell into the pan while I was washing, so you can see how I have been handicapped. The wound is open and pus discharges continually, so much so that I cannot go into any society for fear of offending anyone. I do not belong to any society except the Methodist Church and the G.A.R. My left eye is blind, my hearing is bad and infirmities of old age are creeping on my. I was eighty-two years old on the fourteenth of August, 1920.

I have no kick coming against any one for my condition. If it was possible for me to meet the deluded enemy that shot me I should congratulate him on being a center shot, for that gives me the name of “Center Shot.” I am proud of my wound and of my service, and am glad that I was a small link in that great chain of soldiary that brought back Old Glory without a single star missing.

September 18, 2015

September 18, 1863. “Presently, Crash! came their artillery.”

From the journal of John C. McLain, 4th Michigan Cavalry, Minty’s Brigade; at Reed’s Bridge.

Friday,

September 18.

Cloudy and cold this morning. No orders for moving until 11 A.M. Boots and saddles sounded and we went out on the double quick to meet the rebs. They were advancing, we had some sharp skirmishing. We were driven slowly back across the Chickamauga. We formed in line on the west bank of the creek. They threw shell among us pretty lively, killing my horse under me and wounding Cap. Pritchard. I went to the wagons with my saddle. After I left Charley Rickard was killed and Ferman wounded. They sent Charley’s horse back to me and Ferman’s for George Munger, his horse was shot. A sharp fight after dark.

McLain’s account is rather terse. Captain Henry A. Potter, also of the 4th Michigan Cavalry, has left us a more detailed description:

Fri – Sept. 18th

Cool and cloudy – autumn weather, ordered to saddle up at 4 A.M. expecting to move – but at 7 A.M. stable call was blown. we unsaddled and fed our horses. At 10 A.M. I was ordered to go out with my company under Capt Pritchard and “L” co & reinforce the 7th Penn, as word was sent in that they were attacked by a heavy force of the enemy. Before we were ready to move “Boots and Saddles” blew at Brigade Hd’Qrs, but H & L Cos were in the advance.

When we came up there was considerable skirmishing. I was ordered to move to the right to prevent a flank movement. Moved down in the camp [at Peeler’s Mill] we occupied the first night & farther on into a road where we had a view of the rebel line. They were in strong force. Artillery was plainly visible in the road. A strong flanking party of the rebels moved to our right, when I was ordered to fall back. The 4th regulars were on the right.

Moved back and joined the battalion. We then rode into a cornfield on our right & onto a hill to support our section of artillery. From that view I could see by the clouds of dust a heavy column coming towards us on the left. Our guns presently opened upon them. We were answered promptly by the rebels with four pieces. I could see them when they loaded.

As soon as the smoke cleared away orders came to fall back, which we did. We rejoined the regiment & moved to the left of the road & in line of battle moved through the woods. Our skirmishers soon saw the rebel infantry. We dismounted half of the men and moved upon them. A smart skirmish ensued but [we] were obliged to fall back by overpowering numbers. Formed in line again, again were driven back. Passed through our [new] camp and past the Regulars, towards the river which we succeeded in crossing without loss.

Formed in line on the left to cover the retreat of the 4th [Regulars] presently Crash! came their artillery in the midst of us. A shell passed a few feet over my head & wounded one of my men seriously – Chas. Hall – and two horses. We broke to the right under cover of the woods. Here Capt. Pritchard was wounded in the arm by a shell. Again we formed & dismounted to fight on foot, sending the men toward and along the river. From the left where I was sent to watch for them, I saw three separate lines of their infantry move from the left & swing around towards the bridge.

I sent word to Major Gray to that effect and he moved the regiment back once more into the woods, skirmishing all the time. Wilder’s force was in our rear. But Col. Minty received orders from General [Thomas J.] Wood to fall back to Gordon’s Mills, which we did by 5 o’clock. The enemy followed us closely, & firing in our rear. At dusk heavy skirmishing was heard on the road we came in on. We went out there, our regiment to support the 59th ohio and 44th Ind. Infantry. A sharp fight took place.

The darkness putting and end to the day’s work, we remained as pickets during the night. The men suffered from cold & hunger. Not a mouthful since breakfast. Such a cold night is seldom felt at home in Sept.

David A. Powell's Blog

- David A. Powell's profile

- 28 followers