David W. Berner's Blog, page 4

October 18, 2017

Best Book Titles?

I have been playing around with a newly "completed" manuscript, tinkering really. Actually, I'm not doing much of anything. An editor that I greatly respect has just finished combing it for...issues. She's been doing all the work. At the top of that manuscript is a title, and right below it, a second title, an alternate. The first is more poetic than the other, you might say, but the second is more succinct and clear.

"Which one do you like?" I asked. She chose the first over the second because the subtitle included words she believed were essential to the meaning of the manuscript. The second, she thought, included a word that was probably overused. Several others have read the manuscript and they made the same conclusion. So, was it a visceral response? Was it sheer math? (Too many other books with the same title or combination of words—think: The Girl With the...) Or was it something else, something that's hard to get one's head or heart around? Mysterious? Challenging? Compelling? What is it that makes a great title?

"Which one do you like?" I asked. She chose the first over the second because the subtitle included words she believed were essential to the meaning of the manuscript. The second, she thought, included a word that was probably overused. Several others have read the manuscript and they made the same conclusion. So, was it a visceral response? Was it sheer math? (Too many other books with the same title or combination of words—think: The Girl With the...) Or was it something else, something that's hard to get one's head or heart around? Mysterious? Challenging? Compelling? What is it that makes a great title?

Great books are memorable in their entirety; they're great stories. But many times, books stand out simply because of the title. And there are the few that are great literature and possess wonderful, unforgettable names.

To Kill a Mockingbird

To Kill a Mockingbird

What a fantastic title! Now, put that up against another great piece of literature.

War and Peace

Frankly, too general. I can't imagine a publisher today agreeing with Tolstoy on that one.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Marvelous!

A Confederacy of Dunes

Perfect.

Everything I Never Told You

How could you not pick up Celeste Ng's book and not read at least the first page?

It reminds me of another intriguing one.

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

You also have the absurdly silly or provocative. The novelty acts.

Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs

John Dies at the End

Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs

Steal This Book

And the titles lifted from other works of literature.

Of Mice and Men —Steinbeck snatched the phrase from the Robert Burns poem, "The Mouse."

As I Lay Dying —Faulkner took it from Homer's The Odyssey.

A Farewell to Arms —Hemingway lifted this title from a poem by the Elizabethan writer, George Peele.

The worst titles? Far too many to mention. But try these on for size.

The worst titles? Far too many to mention. But try these on for size.

I Heart You, You Haunt Me

Really?

How to Poo at Work

Yep, a real book.

Your favorite titles? Or maybe the worst you've ever seen? Let's hear them.

"Which one do you like?" I asked. She chose the first over the second because the subtitle included words she believed were essential to the meaning of the manuscript. The second, she thought, included a word that was probably overused. Several others have read the manuscript and they made the same conclusion. So, was it a visceral response? Was it sheer math? (Too many other books with the same title or combination of words—think: The Girl With the...) Or was it something else, something that's hard to get one's head or heart around? Mysterious? Challenging? Compelling? What is it that makes a great title?

"Which one do you like?" I asked. She chose the first over the second because the subtitle included words she believed were essential to the meaning of the manuscript. The second, she thought, included a word that was probably overused. Several others have read the manuscript and they made the same conclusion. So, was it a visceral response? Was it sheer math? (Too many other books with the same title or combination of words—think: The Girl With the...) Or was it something else, something that's hard to get one's head or heart around? Mysterious? Challenging? Compelling? What is it that makes a great title?Great books are memorable in their entirety; they're great stories. But many times, books stand out simply because of the title. And there are the few that are great literature and possess wonderful, unforgettable names.

To Kill a Mockingbird

To Kill a Mockingbird

What a fantastic title! Now, put that up against another great piece of literature.

War and Peace

Frankly, too general. I can't imagine a publisher today agreeing with Tolstoy on that one.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Marvelous!

A Confederacy of Dunes

Perfect.

Everything I Never Told You

How could you not pick up Celeste Ng's book and not read at least the first page?

It reminds me of another intriguing one.

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

You also have the absurdly silly or provocative. The novelty acts.

Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs

John Dies at the End

Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs

Steal This Book

And the titles lifted from other works of literature.

Of Mice and Men —Steinbeck snatched the phrase from the Robert Burns poem, "The Mouse."

As I Lay Dying —Faulkner took it from Homer's The Odyssey.

A Farewell to Arms —Hemingway lifted this title from a poem by the Elizabethan writer, George Peele.

The worst titles? Far too many to mention. But try these on for size.

The worst titles? Far too many to mention. But try these on for size.I Heart You, You Haunt Me

Really?

How to Poo at Work

Yep, a real book.

Your favorite titles? Or maybe the worst you've ever seen? Let's hear them.

Published on October 18, 2017 14:15

October 4, 2017

I Hate My Writing

I'm at a five-way intersection. It's midnight. My headlights are not working. There are no street lights. A few street signs point to destinations but the signs are old or have been mangled by minor accidents of the past, they are twisted and no longer point to their designated endpoint. I know where I'm going, or should I say I know where I want to be, where I want to end up, but the road there is unclear. So, here I sit, inside my vehicle with no map, no wifi, no cell service, mildly paralyzed.

This is exactly how I feel about where I am with my writing. I have two unpublished manuscripts that have been read by several reviewers, being read by several more, edited several times, tweaked and re-tweaked, and are making the rounds of publishers who accept unsolicited works. I feel good about them. I have a third in its infancy. More like the embryo stage. It's memoir, unconventional, and at this point in the process is little more than journals full of notes and computer files of documents. So, the work awaits.

And in the meantime, I hate my writing.

I've recently conducted readings from my published books and I despise what I'm hearing. Those in attendance appear to be pleased enough, but I hate my words. I want to rework everything, change the sentences, rewrite the paragraphs, redo it all.

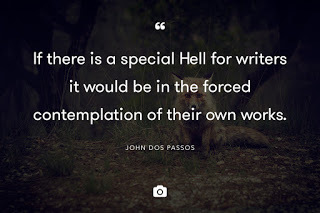

Why is this?

A few other writers say they have experienced some form of this self-hate, this self-loathing. Is it the final self-realization that you truly are a crappy writer? I've been told it's just a matter of growth. You have grown as a writer and your earlier books don't stand up to what you expect from yourself now. That sounds like a pretty good excuse, doesn't it? Oh, I'm just better now. That's why those books suck! This appears far too convenient of an explanation.

I sulk. I pout. I wallow in frustration. Do I keep writing? Do I keep querying with new work? Do I give it all up completely and toss those earlier books in the trash? My publishers liked them enough, right? Do they still like them? One publisher told me this aversion to your own words is not so unusual. Every writer, at some moment in time, rejects their own writing. Not uncommon for all kinds of artists, he said. His cure? Go read a successful book that is poorly written. There are plenty of them, he insisted.

Kurt Vonnegut was said to have graded his published works, giving Happy Birthday Wanda June and Slapstick Ds. The critics didn't like these much either. And Franz Kafka famously asked a good friend to destroy all of his works after his death. Of course, the friend did not. So, knowing even the greats hated their words is supposed to bring comfort?

Sometimes I feel like I'm practicing and not really writing. So I remain at that dark intersection. My car stalled; my headlights still not working. Not sure where to turn next or how long I'll sit here. Not sure where my writing story is going. I wait for a sign, a flicker of light, the dawn, something to show me and this old jalopy the way to go.

Maybe I should just take the bus.

This is exactly how I feel about where I am with my writing. I have two unpublished manuscripts that have been read by several reviewers, being read by several more, edited several times, tweaked and re-tweaked, and are making the rounds of publishers who accept unsolicited works. I feel good about them. I have a third in its infancy. More like the embryo stage. It's memoir, unconventional, and at this point in the process is little more than journals full of notes and computer files of documents. So, the work awaits.

And in the meantime, I hate my writing.

I've recently conducted readings from my published books and I despise what I'm hearing. Those in attendance appear to be pleased enough, but I hate my words. I want to rework everything, change the sentences, rewrite the paragraphs, redo it all.

Why is this?

A few other writers say they have experienced some form of this self-hate, this self-loathing. Is it the final self-realization that you truly are a crappy writer? I've been told it's just a matter of growth. You have grown as a writer and your earlier books don't stand up to what you expect from yourself now. That sounds like a pretty good excuse, doesn't it? Oh, I'm just better now. That's why those books suck! This appears far too convenient of an explanation.

I sulk. I pout. I wallow in frustration. Do I keep writing? Do I keep querying with new work? Do I give it all up completely and toss those earlier books in the trash? My publishers liked them enough, right? Do they still like them? One publisher told me this aversion to your own words is not so unusual. Every writer, at some moment in time, rejects their own writing. Not uncommon for all kinds of artists, he said. His cure? Go read a successful book that is poorly written. There are plenty of them, he insisted.

Kurt Vonnegut was said to have graded his published works, giving Happy Birthday Wanda June and Slapstick Ds. The critics didn't like these much either. And Franz Kafka famously asked a good friend to destroy all of his works after his death. Of course, the friend did not. So, knowing even the greats hated their words is supposed to bring comfort?

Sometimes I feel like I'm practicing and not really writing. So I remain at that dark intersection. My car stalled; my headlights still not working. Not sure where to turn next or how long I'll sit here. Not sure where my writing story is going. I wait for a sign, a flicker of light, the dawn, something to show me and this old jalopy the way to go.

Maybe I should just take the bus.

Published on October 04, 2017 14:18

September 21, 2017

What Makes Great Literature?

I have worked in broadcasting for 40 years in different cities, in varied genres, and I think I know what makes great radio. It's relevant, pertinent, compelling, authentic content. It can be delivered and presented in many ways, but the test is how it resonates with the listener—is it worthwhile and memorable. This I know.

But what about literature? What makes great literature?

I remember a New York Times article that tried to answer that question. It listed several aspects that contribute to a great book: It's a good read; It's quotable; It's memorable; It touches people. Those seem rather pedestrian to me.

In a recent interview, literary rock star Karl Ove Knausgaard said good books had as the main attribute an element of "resistance." Bad books, he said, one could "glide through like a knife through butter." That cliche surely wouldn't show up in a "good" book. But, nonetheless. He suggested that literary rebellion is superior to familiarity. That may be part of it. But is it that simple?

How about these attributes: The high quality of language; The complexity of theme; The element of universality; It's re-readable. Pretty good. But the truth is, great literature is hard to define.

If this is true, then how are the big literary awards chosen? Why does a book get a Pulitzer, a Man Booker? How is a Nobel chosen? What are the criteria?

A blog post a few years ago by author and academic Anne Trubek was critical of the awards. She asked why are the elements of what makes a great piece of literature not clearly explained? Trubek recalled a conversation with a board member of the National Book Critics Circle about the organization's annual fiction award and why a certain work was not chosen.

The reason?

Characters.

The characters, at least one, must be highly memorable. In this particular book, they were not. This may be the ultimate criterion. Fiction, memoir, creative nonfiction—it doesn't matter. Characters are key. Are they unforgettable? Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird. Dean Moriarty in On the Road. Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye. Lizzie Bennet in Pride and Prejudice. Charlotte in Charlotte's Web. Joan Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking.

It might be silly to think that one element of a book holds such weight. But when it comes down to the nitty-gritty, characters are the ultimate test of what makes great literature.

But what about literature? What makes great literature?

I remember a New York Times article that tried to answer that question. It listed several aspects that contribute to a great book: It's a good read; It's quotable; It's memorable; It touches people. Those seem rather pedestrian to me.

In a recent interview, literary rock star Karl Ove Knausgaard said good books had as the main attribute an element of "resistance." Bad books, he said, one could "glide through like a knife through butter." That cliche surely wouldn't show up in a "good" book. But, nonetheless. He suggested that literary rebellion is superior to familiarity. That may be part of it. But is it that simple?

How about these attributes: The high quality of language; The complexity of theme; The element of universality; It's re-readable. Pretty good. But the truth is, great literature is hard to define.

If this is true, then how are the big literary awards chosen? Why does a book get a Pulitzer, a Man Booker? How is a Nobel chosen? What are the criteria?

A blog post a few years ago by author and academic Anne Trubek was critical of the awards. She asked why are the elements of what makes a great piece of literature not clearly explained? Trubek recalled a conversation with a board member of the National Book Critics Circle about the organization's annual fiction award and why a certain work was not chosen.

The reason?

Characters.

The characters, at least one, must be highly memorable. In this particular book, they were not. This may be the ultimate criterion. Fiction, memoir, creative nonfiction—it doesn't matter. Characters are key. Are they unforgettable? Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird. Dean Moriarty in On the Road. Holden Caulfield in The Catcher in the Rye. Lizzie Bennet in Pride and Prejudice. Charlotte in Charlotte's Web. Joan Didion in The Year of Magical Thinking.

It might be silly to think that one element of a book holds such weight. But when it comes down to the nitty-gritty, characters are the ultimate test of what makes great literature.

Published on September 21, 2017 17:12