Robyn Mundy's Blog, page 3

March 29, 2017

Image of the Week

[image error]

In our final weeks at Maatsuyker Island, my partner Gary and I had the joy of sharing the island with the Friends of Maatsuyker Island (FOMI), a fun-filled volunteer group who visit the island each year for an intensive working bee. Amongst the hard workers was photographer James Stone. On the second morning of FOMI’s stay, I made my way down to the lighthouse at first light to carry out a routine daily check. Rounding the corner I did a double take at the sight of a camera and tripod standing untethered on the path, where it had stood overnight. With the relentless winds at Maatsuyker, snagging a time when you might find your camera and tripod in the same place as you left it is a noteworthy event in itself. But when I saw the results of James’ photography, the aurora shown above, and a second image below, I was the one blown away. I invited James to share the story behind his stellar images.

[image error]As a night sky photographer and self-confessed aurora-addict I couldn’t believe my luck when an aurora was predicted for my first couple of nights on Maatsuyker Island, Australia’s southernmost lighthouse and maybe the best location from which to view the Aurora Australis or Southern Lights outside of spending a winter in the Antarctic. This was in conjunction with clear skies and no wind – conditions exceedingly rare on this exposed lump of rock in the Southern Ocean, renowned for being amongst the wettest and windiest places in Australia. Despite a very early start to get to Maatsuyker I knew I had to stay up and make the most of this incredible opportunity.

The lighthouse stood as a stoic sentinel as the lights danced high in the sky behind, the peace of night broken only by the cries and bellows of the seals on the rocks far below, and the occasional muttonbird swooping by. Being my first night on the island, and with restoration work going on in the lighthouse, I wasn’t sure if I should venture inside, but chanced sticking my head through the door to shine my headtorch up the stairwell, illuminating the windows and lantern room for effect. I would loved to have posed for a silhouette shot on the upper gantry but didn’t think I had better risk it without permission. Next time…

I watched the display long into the wee hours of the morning, in awe of not only the stunning night sky, but my spectacular good fortune to be able to be there, in that location, under those conditions, a unique and truly memorable experience.

Eventually tiredness overtook me and, placing my tripod in a sheltered spot out of the wind and flightpaths of birds, I left my camera clicking away shooting a time lapse until its battery ran out. Meanwhile I staggered back up the hill to bed.

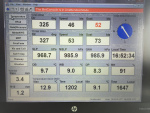

For keen night-sky photographers, James shares his camera settings, and a second aurora image below: Camera: Nikon D750, Lens: Nikkor 16–35mm f/4, Exposure: 20seconds @ f/4.0, ISO: 5000. Be sure to check out James’ brilliant time lapse sequence on Vimeo.

[image error]

Filed under: Image of the week, Maatsuyker Island Tagged: aurora australis, Friends of Maatsuyker Island, James Stone, Maatsuyker Island, photography, southern lights

March 22, 2017

Beneath the rainbow

[image error]

Any title that includes Rainbow is bound to conjure images of crystals and incense sticks. Rest assured there is no tinkle of glass or whiff of sandalwood throughout this post, only photographic proof that it is possible to see the end of the rainbow, and to live beneath it. We’re talking Maatsuyker Island, site of Australia’s southernmost lighthouse, the island where my novel Wildlight plays out, within cooee of the the south-west corner of Tasmania.

Our six months of caretaking and weather observing at Maatsuyker Island has come to a close. Now, even more than our first few days of treading paved roads, it feels like crashing back to earth. The work on the island was hard, the living conditions cold, and the wind rarely stopped blowing, but perhaps all these challenges contributed to us having the time of our lives. Despite turning into eating machines we each left the island many kilograms lighter, and fitter, thanks to hauling lawnmowers up and down slopes, wielding brush cutters, digging drains and tending a large vegetable garden, plus kilometres of walking. It’s a win-win formula that I’m naming The Maatsuyker Diet.

[image error]

Here is my partner Gary with ‘Helga’ the mower. There’s little scope for traditional gender roles on Maatsuyker Island. We divided the mowing and brush cutting work that tends a 2-kilometre-long grass road, 2 helicopter pads, 1 vegetable garden, the surrounds of 3 cottages and 1 lighthouse, 1 paddock, and brush cutting 7 bush tracks, paths and numerous slopes too tricky or hazardous to mow. One round took each of us 4–5 days on a 3-weekly cycle.

A corner of the Maatsuyker pantry at the start of our stay; strawberries from the veggie garden’s poly house; sushi rolls for dinner (my partner Gary’s speciality); during our stay we consumed 42 kgs flour transformed into sourdough loaves and baked goods.

During our first caretaking term in 2010–11 we barely saw another two-legged being, but on this recent stint we relished the company of several energetic visitors. Long-time friends Katherine and Kevin from Western Australia arrived on a crayfishing boat and stayed for five days. The permits and arrangements took them months, and even then it was nail biting times as the ocean swell and weather was against them both on their arrival and throughout their stay. Katherine and Kev were thankful for the handrails in the howling gales; they very quickly found their footing, embraced nature, and contributed to Maatsuyker with all manner of island work.

The wonderful Friends of Maatsuyker stayed over for two intensive working bees. This volunteer group contributes to almost every aspect of the island. Amongst the hard workers was Mark, who has turned his passion for lighthouses into restoring those around Australia that require serious TLC. Mark made his own way down to Tasmania and donated time and skills to continue work on restoring Maatsuyker’s lighthouse. During his days on the island we would regularly cross paths at first light as he headed down the hill to begin his day, working until late into the nights. He made impressive progress by removing damaging paint from a big section of the inside walls, and repainting top parts of the tower.

An unexpected visitation came from Dutch presenter-producer Floortje Dessing and her camerawoman Renée, who flew all the way from the Netherlands at short notice to produce a documentary about life as caretakers on Maatsuyker Island. Floortje To the End of the World (Floortje Naar Het Einde Van De Wereld) is a popular Dutch TV series that focusses as much on the people who choose to live in remote corners of the world as it does on the the natural wonders of wild places. While they were on Maatsuyker the girls got to experience the brunt of the Roaring Forties latitudes with 6-metre ocean swells and a record wind gust for January. Maatsuyker claims plenty of ‘personal bests’ when it comes to record winds: still unbroken is its August 1991 squall of 112 knots (207.4 kms per hour), the country’s highest non-cyclonic wind gust. Floortje and Renée embraced every moment of the weather and were fun to be with. I only learned later how big a celebrity Floortje is in her home country, while to us they were simply two sparkling, down-to-earth women who joined us each evening for dinner, washed up afterwards, brought a whopping great round of Edam cheese in their suitcase and followed us here and there on our daily routines.

[image error]

Lastly we welcomed Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife video competition winner Simon whose prize was a visit to Maatsuyker Island. Simon and his mate Noodle lobbed in for an overnight stay via helicopter, though with under-par weather conditions it was touch and go whether they could even make it to the island. Thanks to the skilled pilots at HeliRes they arrived safely and with only a short delay. Without losing a minute, the boys donned wet weather gear and bounded from one end of the island to the other with cameras in tow. In the evening, between ducking outdoors to watch a brilliant sunset, they joined us at Quarters 1 for curry and a pint of home brew beer. Next morning at 0400 they were up and at ’em to watch Maatsuyker’s thousands of short-tailed shearwaters launch off the island. In 24 hours Simon and Noodle succeeded in filming and later producing a professional 3-minute video which showcases the island. I will have that clip available to share in a week or so, along with an interview with Simon.

I could go on about Maatsuyker, but will close with the info below and a selection of photos which I hope express the magic of the island.

The nitty gritty of caretaking at Maatsuyker Island

The volunteer caretaker program is coordinated and managed by Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service who currently advertise the position through Wildcare Inc. every two years. Each applicant must demonstrate a range of skills and an adequate level of physical fitness, and will be responsible for purchasing their own provisions for the six-month term. Part of the Maatsuyker caretaker duties is to conduct daily weather observations for the Bureau of Meteorology Hobart. Many short-term volunteer caretaking opportunities across Tasmania are advertised through Wildcare Inc., the incorporated community partner organisation that provides management and support for volunteers working in natural and cultural heritage conservation and reserve management. Friends of Maatsuyker Island (Wildcare Inc.) is a volunteer group who contribute time and skills to the island, raise funds towards maintenance and improvements on Maatsuyker, run day trips to the island via boat, and conduct annual working bees.

Filed under: Maatsuyker Island, Uncategorized, Wildlight Tagged: adventure travel, Bureau of Meteorology, Floortje, Floortje Dessing, Floortje Naar Het Einde Van De Wereld, Friends of Maatsuyker Island, Helicopter Resources, lighthouse, Maatsuyker Island, photography, Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife, Wildcare Inc., Wildlight, writing

September 9, 2016

Last gasp of a big year

With my times away from home, my blogging pattern tends to be feast or famine. This week sees no nutritional lack. Despite spotty attendance I feel great personal reward in the interactions with readers and guests that maintaining a website generates. Imagine, then, a world with no internet, no email and no mobile coverage; then—as daunting as the prospect may be—picture me in that world for the next six months. Shortly, my partner Gary and I are off to remote Maatsuyker Island, site of Australia’s southernmost lighthouse, for a second term as volunteer caretakers and weather observers. While the island remains happily rodent and snake-free, it also remains staunchly internet-free, just like its old light keeping days, minus the carrier pigeons.

With my times away from home, my blogging pattern tends to be feast or famine. This week sees no nutritional lack. Despite spotty attendance I feel great personal reward in the interactions with readers and guests that maintaining a website generates. Imagine, then, a world with no internet, no email and no mobile coverage; then—as daunting as the prospect may be—picture me in that world for the next six months. Shortly, my partner Gary and I are off to remote Maatsuyker Island, site of Australia’s southernmost lighthouse, for a second term as volunteer caretakers and weather observers. While the island remains happily rodent and snake-free, it also remains staunchly internet-free, just like its old light keeping days, minus the carrier pigeons.

Maatsuyker Island with Needle Rocks in foreground. ©Robyn Mundy

This has been a mega year for me with the launch of my second novel, Wildlight, a story set on Maatsuyker Island. I feel personally touched to have had many lovely responses from readers who in different ways have been moved by the story, along with the relief any writer feels on receiving favourable media reviews. This doesn’t come without the sting of the odd 1- or 2-star reader rating on Goodreads, but—Man-up, Robyn!—such is the nature of writing and reading. This year I also feel fortunate to be amongst the lucky few to receive a grant from Australia Council for the Arts toward my new novel in progress. Thank you, ACA, for considering the project worthy of support. Those of us who throw our hats into the ring for such funding understand how competitive and slim the prospects. There are so many talented writers deserving of success, combined with brutal slashes in funding for Australian Arts.

Between ship work and writing research, it’s been a scramble preparing for Maatsuyker Island, months in the planning with the need to provide 6 months of provisions for our island time. Imagine running short of coffee. Or wine. Or chocolate! Imagine forgetting to take books to read. It has been the mother of all shopping lists, let me tell you. As seasoned caretakers on Maatsuyker there will be no shortage of lawn mowing, brush cutting or maintenance tasks; thankfully, there will still be ample time to savour the beautiful island surrounds and to make solid progress on my new novel. Novel 3 will not be a sequel to Wildlight, though my Auntie Muriel is keen to know why I refused to write Wildlight‘s final chapter. :-) This new story is set in a vastly different wilderness, about as far away from Maatsuyker Island as is probable to venture.

Earlier in the year I was invited to write an article for Newswrite magazine on what attracts writers like myself to wild places. With permission from the New South Wales Writers’ Centre, I have reproduced the article below.

For now and always, keep safe and happy. Keep loving books. More from Writing the Wild in March 2017.

Robyn x

———————-

Writing the Wild

This article first appeared in Newswrite Magazine, June 2016, and is reproduced here with permission of the New South Wales Writers’ Centre.

When asked to consider why, as a writer, I feel drawn to wild places and isolation, I initially grappled for an answer, which led to this confession: forget about being a writer; the urge to experience places such as Maatsuyker Island and Antarctica where my novels are set, originates from purely self-seeking motives, from some deep well of longing to experience nature. As a novelist, the fascination for wilderness precedes all else; from immersion in its landscape comes story.

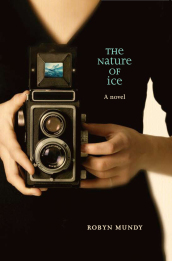

My first novel, The Nature of Ice, draws on Antarctica, the backdrop of my life for nearly 20 years. I have wintered and summered at Australian Antarctic stations, working as a field assistant on science research projects that included a remarkable winter on the sea ice with emperor penguins. I am doubly fortunate to spend several months each year aboard a small ice-strengthened vessel, guiding adventure tours to Antarctica, the Arctic, and other wondrous outposts.

My first novel, The Nature of Ice, draws on Antarctica, the backdrop of my life for nearly 20 years. I have wintered and summered at Australian Antarctic stations, working as a field assistant on science research projects that included a remarkable winter on the sea ice with emperor penguins. I am doubly fortunate to spend several months each year aboard a small ice-strengthened vessel, guiding adventure tours to Antarctica, the Arctic, and other wondrous outposts.

While the Antarctic wildlife rates as a huge drawcard, the ultimate spellbinding seduction for me is the ice. Being within it. That is not to imply some trippy state of serenity. If wonder is one face of awe, the other is a guarded caution in knowing how easily Antarctica can turn from beauty to malevolence. You can’t be in a wild place for long without respect for its might.

The first draw to Antarctica began with someone else’s story. As a young adult I read Lennard Bickel’s This Accursed Land, a dramatised account of polar explorer Douglas Mawson’s 1911–14 Australasian Antarctic Expedition. Along with the iconic images of photographer Frank Hurley, the story of that thwarted expedition ignited my curiosity and imagination. How might such a hostile place feel, where nature determines everything? I had to find a way to go.

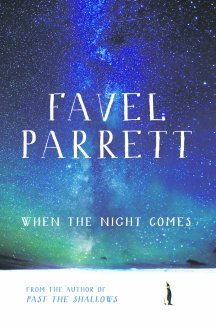

As a contemporary Antarctic novelist, I am not alone in this draw to the frozen south. Favel Parret’s When the Night Comes has its origin in the history of Nella Dan, a former Australian Antarctic supply vessel. I posed the question to Favel: what attracts you to wild places?

As a contemporary Antarctic novelist, I am not alone in this draw to the frozen south. Favel Parret’s When the Night Comes has its origin in the history of Nella Dan, a former Australian Antarctic supply vessel. I posed the question to Favel: what attracts you to wild places?

‘At first I was drawn back into my childhood memories of the south of Tasmania. Mostly it was the child’s fear of the wild that I wanted to understand. Then at 27 came surfing and the feeling of wanting to be on the wild water, and wanting to find remote wild beaches that were pristine and free of concrete car parks and cars and houses. The clean waters of Bass Strait and the Southern Ocean became vitally important to me.’

Reflecting on the genesis of When the Night Comes: ‘Nella came first. I had to follow her and experience where she went. I had to go to sea and visit the Southern Ocean properly. On my first trip, to Macquarie Island, I found that I was in love with seabirds and could easily spend the rest of my life watching them. That trip was not enough; I had only scratched the surface and I knew I had to go to the ice. It was wonderful to experience Antarctica for the ten-day resupply at Casey Station, but it was the long journey at sea that felt most wild. The moments always changing, the ship always moving, new birds to watch, different whales to see, different swells to navigate. The wildness of that ocean speaks to me in so many ways and I would go again in a heartbeat. It is the wildest place I know.’

Author Jesse Blackadder also travelled south to understand Antarctica. Her novel Chasing the Light draws on the 1930s history of Ingrid Christensen, wife of a Norwegian whaling magnate. Ingrid and two unlikely female companions are each poised to become the first woman to land on Antarctica. Serendipitously, I recently met up with Jesse and asked which came first, the draw to Antarctica, or Ingrid’s story? Like me, like Ingrid Christensen, Jesse’s personal longing to experience Antarctica stretched back years, driven, in Jesse’s case, by images of wildlife and ice. Place first, story second.

Author Jesse Blackadder also travelled south to understand Antarctica. Her novel Chasing the Light draws on the 1930s history of Ingrid Christensen, wife of a Norwegian whaling magnate. Ingrid and two unlikely female companions are each poised to become the first woman to land on Antarctica. Serendipitously, I recently met up with Jesse and asked which came first, the draw to Antarctica, or Ingrid’s story? Like me, like Ingrid Christensen, Jesse’s personal longing to experience Antarctica stretched back years, driven, in Jesse’s case, by images of wildlife and ice. Place first, story second.

All three Antarctic novels are fictional works inspired by history, yet the authors’ personal experience infuses an undeniable verisimilitude into their sense of place. Similarly, the voyage across a vast Southern Ocean to reach Antarctica is as fundamental to each story’s narrative arc as it is to the writer’s personal quest. For writers where place sits at the forefront of the work, it behoves us to connect with its landscape, to fully know it through personal experience or memory or research.

My new novel Wildlight plays out on remote Maatsuyker Island off Tasmania’s South West. Here, my partner Gary and I spent four months living in isolation as volunteer caretakers and weather observers. The inspiration for Maatsuyker Island was triggered by a childhood at our family shack on the edge of the ocean. Maatsuyker amounted to a dot on the wall map, to a reputation for wild weather and the home of Australia’s southernmost lighthouse. Evening weather reports on Dad’s crackly transistor radio conjured images of light keepers trudging to and from the lighthouse in knockdown gales, of a place riven by storm and fearsome seas. As a child I wanted to know such a place. As an adult, I wanted to write it. Yet I couldn’t—not with credibility—until I had experienced it.

My new novel Wildlight plays out on remote Maatsuyker Island off Tasmania’s South West. Here, my partner Gary and I spent four months living in isolation as volunteer caretakers and weather observers. The inspiration for Maatsuyker Island was triggered by a childhood at our family shack on the edge of the ocean. Maatsuyker amounted to a dot on the wall map, to a reputation for wild weather and the home of Australia’s southernmost lighthouse. Evening weather reports on Dad’s crackly transistor radio conjured images of light keepers trudging to and from the lighthouse in knockdown gales, of a place riven by storm and fearsome seas. As a child I wanted to know such a place. As an adult, I wanted to write it. Yet I couldn’t—not with credibility—until I had experienced it.

The sheer force of wild landscapes—their capacity to slough away the noise and clutter of urban life, to command our full attention, to beguile us with their majesty then strike with their hostility—preoccupies me as both a novelist and traveller. Each season on polar voyages I see fellow travellers ‘expanded’ by these other worlds. For some, like me, the experience is a form of meditation, the likes of which is largely unattainable in the workaday world. For others, the journey may mark a pivotal turning point. As sites of transformation, places of wilderness offer a bounty of riches for literary fiction.

It feels important to qualify that a love of nature—of any landscape—is not sufficient to sustain a work of fiction. Within the layers of a compelling story lies human conflict. It must. ‘Without the friction of conflict,’ says author Stephen Fischer, ‘there is no change. And without change, there is no story. A body at rest remains at rest unless it enters into conflict.’

Even during the lead-up to being on Maatsuyker, the anticipation of the island performed its alchemy, stirring characters into being and offering potential conflicts: what would months on Maatsuyker be like for a teenage girl dragged there by her parents, removed from her friends and the comforts of home? What if that family were isolated from each other, grieving for the death of a child? What would the surround of ocean mean for a 19-year-old deckhand who fears the sea and holds a premonition that some day it will take him? And the big question: how do I make best use of island and ocean in a story where these lives collide?

I strive to make place dynamic, to function as a fickle, layered character. Landscape holds a capacity to not only reflect the inner turmoil of characters, but to shape and transform. Who better, it seemed to me, than two young people at odds with their landscape, still making themselves up as they go along?

On a recent walk to a wilderness lookout, I happened upon an interpretative sign with this, by author-environmentalist Aldo Leopold: Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty. It expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language. The challenge for the writer remains one of language: to fathom the meanings of wild places through the characters that inhabit them.

Filed under: Uncategorized, Wildlight, Words for Writers Tagged: Chasing the Light, Favel Parret, Goodreads, Jessie Blackadder, Maatsuyker Island, New South Wales Writers' Centre, Newswrite, When the Night Comes, Wildlight

September 4, 2016

Readers on Reading

In this segment I invite an inspirational reader to share a little of their life and a favourite recent read.

It is a complete accident that we have been born here and now, as we could just as easily have been Neolithic farmers or part of an Inuit hunter’s family. — Carol Knott

Grounded icebergs at Rode Ø (Red Island) in North-East Greenland. ©Robyn Mundy

One of the nicest side benefits of shipboard life is working closely with a small expedition team from around the globe who feel as inspired by the remote places we visit as do our adventurous passengers. Our final voyage for the northern season came to a close a few days ago, our stout little Polar Pioneer having ventured to wild Scotland back in June, then most recently to Svalbard and North-East Greenland in the High Arctic. Our days across the Greenland Sea gave me time to entice onboard archaeologist and historian CAROL KNOTT into sharing a story or two, albeit reluctantly, of her own remarkable life.

Time travel

CK: I have always been fascinated by the idea of exploring time. Our lives are part of a continuum of past, present and future, bound together, for me, by a great sense of common humanity. It is a complete accident that we have been born here and now, as we could just as easily have been Neolithic farmers or part of an Inuit hunter’s family.

At Mousa Broch in the Shetland Isles, Carol recounts stories of feuds and forbidden love that played out within the walls of this formidable iron-age fortress. ©Robyn Mundy

RM: Scotland’s beautiful Isle of Lewis is Carol’s home turf, though she has worked far and wide as a field archaeologist, exploring life as it was lived in previous ages, and sharing her discoveries with 21st century travellers. ‘I remember once holding in my hand a piece of pottery impressed with the potter’s thumbprint, and feeling a sudden shock of direct connection crossing almost 1,000 years.’ Carol is treasured for her ability to infuse the past with life, prompting us—even challenging our assumptions about past and present cultures—to think about new ways of understanding the things we encounter.

One special site has inspired her to explore, first hand, the experience of women from the past; however, like all good character-driven stories, in embarking on one quest, Carol has found herself bounding along an entirely unanticipated trajectory:

Pilgrimage on horseback

© Carol Knott

CK: Sometimes a voyage takes me to Santiago de Compostella in Galicia, Spain, where we witness the arrival of dusty modern-day pilgrims, at the completion of their long Camino to this ancient shrine. It was a remarkable cultural phenomenon in the Middle Ages, and it is even more so today. Inspired by this, four of us, all women, resolved one day to do the Camino ourselves, but to try to do it on horseback, and from Lisbon — the Portuguese Way. We want to examine the experience of women travellers and pilgrims centuries ago, and compare it with our experience as modern women travelling today. I soon realised that my horse-riding skills were rusty in the extreme, so I started to do training rides wherever the opportunity arose.

Carol takes to the reins in Iceland. Icelandic horses, unique in having five natural gaits, are known for their sweet temperament, sure-footedness and ability to cross rough terrain. ©Elena Wimberger, 2016

RM: Before voyages, after voyages, even in the few hours between voyages, Carol has ridden. She has ridden an Icelandic horse in Iceland. She has galloped, gaucho style, across the Patagonian pampas on a horse named Denis. She has taken up the reins in Svalbard, the world’s most northerly place possible to horse ride, with a rifle as protection from polar bears. And she’s ridden at the most southerly: Tierra del Fuego. ‘This quest to ‘ride around the world’, Carols says, ‘has taken on a life of its own, regardless of whether we manage to pull off our horseback pilgrimage.’

Home as anchor

CK: I live on an island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, and I treasure the meaning that adds to my life—a place where the traditional Gaelic culture is strong and informs every aspect of modern life, where people over millennia have come to terms with the realities of living close to nature in what seems like a wild place. Wherever I go in the world, this strong bond to my family home provides me with an anchor that sets me free. This balance between freedom to wander and a deep sense of belonging is something I treasure greatly.

Carol’s favourite recent read:

The Anchoress, by

Robyn Cadwallader

The Anchoress, by

Robyn Cadwallader

CK: I picked up this book as something to read on my way home from Antarctica, and chose it because it touched on my current interest in women’s freedom versus confinement, and also because the paperback was small and portable, ideal for a traveller like myself. But I loved the fact that this thoughtful book, set in thirteenth-century England, portrayed ideas that are so remote from our modern preoccupations. The central character, Sarah, at seventeen, enters a closed cell attached to a church, where she intends to spend the rest of her life as a holy woman in fasting and prayer. Here is a girl whose spiritual journey, and indeed almost all of the action of the book, takes place, not over miles of dusty roads, but within the silence of a cold, dark room only a few paces long. Robyn Cadwallader’s writing makes this appalling prospect sparkle with colour and drama, and takes us, body and soul, deep into the medieval world. It is another great example of how historical fiction can communicate difficult ideas vividly and effectively to a wide readership.

Filed under: Arctic, Readers on reading, Uncategorized Tagged: Archaeology, Carol Knott, Isle of Lewis, Polar Pioneer, Robyn Cadwallader, The Anchoress

August 6, 2016

Image of the Week

Wave: Land’s End Study II. Cape Denison, Antarctica. ©Alasdair McGregor. Gouache on paper, 52 x 38cm.

Wave: Land’s End Study II. Cape Denison, Antarctica. ©Alasdair McGregor. Gouache on paper, 52 x 38cm.

Imagine being commissioned to paint en plein air at the world’s windiest location recorded at sea level.

Meet my friend and shipboard colleague Alasdair McGregor. If Alasdair wasn’t such a nice guy, he could be really irritating. That’s because he can rightfully lay claim to not one but several creative talents.

Alasdair began his working life as a professionally trained architect but has devoted years to writing and painting, esteemed in both regards. Alasdair has written numerous books: you name it: natural history, architecture and design, biography, great explorers. With my own Antarctic background, one of my faves is his brilliant biography Frank Hurley: A Photographer’s Life.

As a writer and visual artist, Alasdair has spent significant creative time in Antarctica. In the 1980s he took part in a mountaineering expedition to sub-Antarctic Heard Island. In the late 1990s he was artist and photographer for two expeditions to Mawson’s Huts at Cape Denison in Commonwealth Bay, recorded as the windiest place on earth at sea level. Alasdair’s painting, Wave: Land’s End Study II, comes from his Commonwealth Bay experience. Here is what he has to say about it.

Spending seven weeks in early 1998 camped on the ice at Cape Denison was an immense physical and artistic challenge for me. For a plein air artist, it was not just the cold, but the ferocious winds for which this stretch of Antarctic coast is justly infamous that had me apprehensive from the start. But I need not have worried. There were fine and calm moments every few days and I made the most of them. I was particularly fascinated by the spectacular ice cliffs that stretched away to the horizon to the east and west of the tiny cape. The cliffs were the physical, and in many ways, the psychological limits of our existence. So near and yet untouchable, I would venture to what Mawson’s expedition dubbed Land’s End and John O’Groats to paint the cliffs in all lights and at all times of day. To me they the essence of frozen motion and this is what I sought to capture in my work.

Learn more about Alasdair and his wonderful creations at www.alasdairmcgregor.com.au

Filed under: Image of the week, Uncategorized Tagged: Alasdair McGregor, Antarctica, Commonwealth Bay, en plein air

July 18, 2016

Desert Island Books, a survival guide

A little while ago I received a request that was dear to my heart: Robyn Mundy (author of Wildlight) is planning a sojourn on Maatsuyker Island. She and her husband are going as volunteer caretakers and weather observers, and (as you know if you took my advice and read Wildlight) they will have no access to email or internet. Naturally, she needs books to read, and she asked me to suggest 15 contemporary novels that I would wish to read if cast away on a remote island for 6 months.

A little while ago I received a request that was dear to my heart: Robyn Mundy (author of Wildlight) is planning a sojourn on Maatsuyker Island. She and her husband are going as volunteer caretakers and weather observers, and (as you know if you took my advice and read Wildlight) they will have no access to email or internet. Naturally, she needs books to read, and she asked me to suggest 15 contemporary novels that I would wish to read if cast away on a remote island for 6 months.

This got me thinking about criteria for selection. Clearly Desert Island Books must be able to withstand re-reading, and they need to be long enough, at least, to last the distance. But there’s more to it than that….

I’ve always said that Ulysses by James Joyce is my Desert Island Book because I’ve read it four times and each time I’ve found…

View original post 631 more words

Filed under: Uncategorized

July 4, 2016

Kennedy, Saunders…Trump

A thousand apologies, Cate Kennedy and George Saunders, for linking the ‘T’ name with your own, forgiven*, I hope, by the ever-handy ellipsis.

In my last interview post with one of Australia’s national treasures, writer Cate Kennedy, (scroll down, scroll down; wait! read this first) Cate mentioned George Saunders’ short story collection Tenth of December as a favourite read.

‘Tenth of December’, the story after which the collection takes its name, was first published in the New Yorker in October, 2011, and is available to read online (legally, I hasten to add) via www.openculture.com

‘Tenth of December’, the story after which the collection takes its name, was first published in the New Yorker in October, 2011, and is available to read online (legally, I hasten to add) via www.openculture.com

It’s a knock-your-socks-off work. Trust me.

Speaking of Trust Me soothsayers, the infamous Donald Trump recently caught the attention of the aforementioned George Saunders, who also writes as an essayist for the New Yorker. For those flummoxed, intrigued, entertained or rendered aghast by the curious unfolding of the American political stage, Saunders attended a Donald Trump political rally to find out, Who are all these Trump Supporters?

*If not, may the fleas of a thousand camels infest my armpits…

Filed under: Readers on reading, Top Shelf, Uncategorized Tagged: Cate Kennedy, Donald Trump, George Saunders, New Yorker, Tenth of December

June 30, 2016

Top Shelf: interview with Cate Kennedy

During the 2015 Tasmanian Writers and Readers Festival*, I attended a Master Class run by Australian author Cate Kennedy, whose fiction I love, admire and have learned so much from in my own writing journey. I soaked up every minute of the class discussion on writing, along with Cate’s insights in response to questions from fellow writers.

It should come as no surprise that Cate’s short stories have touched thousands of readers. She has won awards for her two collections, Dark Roots and Like a House on Fire. Equally, she was celebrated for her debut novel The World Beneath, with the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards’ People’s Choice. Her poetry collection, The Taste of River Water: New and Selected Poems, was awarded the CJ Dennis Prize in the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards. When I consider that breadth of writing, it’s quite a roll call.

Recently, the gracious Cate eked out time to consider these questions for Top Shelf. Whether you are a reader of fine fiction, an emerging or an established writer, or would simply like to know more about a remarkable story teller, read on.

When did you first realise that writing was something you could excel at?

Cate Kennedy

CK: At school I recall realising I could excel at ‘composition’ and essay-writing, because I was always such a huge reader, but that excelling is a very different thing to stepping out onto the tightrope of creativity. That feels more like renouncing learned expertise, and admitting yourself a beginner every time you sit down at the desk. I was thinking the other day what a long spell of ‘not-writing’ I had when I finished school and university, and realised it was almost exactly the same number of years I’d spent in the education system – fifteen years altogether. So maybe the more important realisation was the unlearning, and then finding compelling enough reasons to return to it after such a long time of avoiding it.

When you look back on your earlier stories, do you see a shift or development in how and what you write now?

CK: I do see a shift when I look back at earlier stories. I see I was more tentative about just trusting my reader to make connections themselves, based on what I was attempting to show them. This is everyone’s early problem, I think: lack of confidence makes us tentative and hesitant, and we don’t take risks, so our writing seems to lack that boldness and verve we strive for. Developing a voice takes a long time and doesn’t seem, to me, to be something you can do abstractly or by theory alone – you have to learn it through the writing. Now I try to worry less, and not overthink it – just imagine a kind of telepathic conversation happening between me and the reader.

I am frequently touched by your capacity to inhabit a character, and to imbue even the most unlikely character with empathy. Farmer Frank Slovak in Flexion comes to mind. Can you speak about these qualities?

CK: Thank you for that response. There’s a temptation to want everything to be simpler and more coherent in a story than it feels in real life, but I keep finding (both in fiction and in real life, actually) that while dilemmas and predicaments can be clear and cogent, humans (and characters) demand a bit more time and effort. We’re complex. We self-sabotage. We’re fallible. For a sense of realism and empathy, and to create character dimension, I keep returning to this question of human fallibility. If a character seems two-dimensional, recognising their complexity and trying to step into their skin to do it feels like a way to humanise them. Then they feel realer to me, and something occurs to me that I can plausibly make happen to them to make what they’re trying to keep hidden break the surface. This is true of ‘antagonists’ as well. Our first instinct is to make a black-and-white world where people get what they deserve and learn a moral lesson, etc etc, because we’re brought up on fables and myths which work to gratify that yearning in us. But to humanise an antagonist, to make a reader practise empathy; when I add those dimensions to a character, another layer opens up. I like that quote “Be kind. Everyone is fighting a great battle.”

Setting modesty aside, what do you feel is the greatest personal quality you bring to your writing?

CK: If I can render effectively the way an ordinary person deals with the crazy shit life throws at them in a way which shows a core of integrity fighting to the surface, I’m happy with that.

The World Beneath is an award-winning debut novel that plays out in the Tasmanian wilderness. Were there particular challenges in shifting from short fiction to writing a novel-length work?

CK: There sure was. Try spinning a plate on a stick so it doesn’t fall off and smash, and when you feel you’ve almost got that under control, try setting up nine more plates to spin perfectly and simultaneously. Oh, and don’t forget you’re doing it in front of an audience. Anyone who’s ever written a novel will know how daunting it is, and how much of your focus and mental energy it demands. I’m deep in the throes of attempting another one, though, so in a way it’s back into the wilderness, trying to find my way out.

As an established writer, do you still draw on feedback from trusted readers as part of your writing process?

CK: I do have a few trusted readers, the people who know my strengths and weaknesses and can point out ‘tics’ which are invisible to me, which can be very enlightening. In the end, though, you’re by yourself in a room, relying on your own instincts, pursuing a vision it’s very difficult to articulate before you’ve got it on paper and can look at it yourself with fresh eyes, to see what you’ve accidentally revealed to yourself. After that tricky generative phase, I’ve found the ‘crafting’ decisions are easier, which is a relief. Getting into a ‘generative’ state of mind, though, is harder – it’s a brainwave state, pretty much, rather than a learned expertise – like daydreaming. The less analysis and second-guessing involved in this state, the better. So I like to have something pretty well-drafted before I show it to anyone else for feedback. Otherwise it can feel like a story written by a committee, and I always feel then like I’ve failed to do my original idea justice. Editorial feedback from a trusted reader whose opinion you respect, though, who’s paying your work close attention: that’s gold.

Can you offer reader-writers a single piece of advice based on your approach to these aspects of craft:

CK: I’ll give it a try!

Character: make up someone who wants something but can’t get it, and doesn’t really get why. Just let them pull you around.

Conflict: The engine of fiction. Try seeing it as duress or pressure. Or heat.

Dialogue: We’re not listening to what’s said, we’re listening for what’s not said.

Language: Sensory, specific, and visceral. Read every day and take note of what moves you.

Openings: Show me someone in revealing action, and trust that I’m paying attention. Set up something you’re going to pay off later, to indicate that you’ve got your hands on the wheel in terms of structure and shape, and I’ll follow you anywhere.

Pace: Here’s a test of the author’s authority – can they control the pace at which their reader is absorbing and comprehending what’s on the page, while making sure they’re completely oriented about why it matters? Can they render ‘blow-by-blow narrative action’ so it feels real and compelling? Can the writing create a physiological response in a reader, like increased heart-rate, tears, or shortness of breath? Is it immersive? Here’s a very simple tip: practise writing good sentences. Vary their length. Let their tone and pace mimic the emotional experience they’re describing. Write so that someone can lose themselves in your subject matter and not be aware of the ‘writing’ itself.

Resolution: The writer, hopefully, has come out of the story a slightly different person than they were when they went in. So, hopefully, has the character. So, if you’ve managed to pull it off in a sort of miraculous alchemical transfer, has the reader.

Closings: Don’t be tempted to tell the reader what you’ve just eloquently shown them. Trust imagery. Pay attention to what happens in life.

Critiquing your own drafts: Read them aloud, in front of strangers. Feels terrible, right? So don’t do that again. Learn to hear your own faults through your own ‘ear’, so you know if you’re in tune, in pitch, or flat, then when they feel as finished as you can make them, share them with someone whose opinion you value, who doesn’t feel the need to shore up your self-esteem.

A favourite recent read?

CK: George Saunders’ Tenth of December is an amazing collection I often dip back into to be inspired by its sheer bravura. Waiting for me on the bedside table is Charlotte Wood’s The Natural Way of Things and Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See.

Finally, and importantly, what is something you treasure about your life?

CK: I treasure having a private life, and all the friends I have made through struggling on with the writing – other writers who’ve turned me in new more coherent directions, enlightening conversations about ideas, the joys of finding your ‘tribe’. And of course, stories. That’s what it’s all about now for me – the relationships and the stories. That’s become the connective tissue. It’s so strange, isn’t it, how creating fictional stories gets you to something that feels so unmistakeably true?

*The next Tasmanian Writers and Readers Festival takes place in Hobart in September 2017

Filed under: Top Shelf, Uncategorized, Words for Writers Tagged: Cate Kennedy, Dark Roots, Like a House on Fire, Tasmanian Writers and Readers Festival, The Taste of River Water, The World Beneath

May 27, 2016

Image of the week

©Robyn Mundy

Soviet Chic 1981

Honestly, who needs a smart phone? There are many things I love about MV Polar Pioneer, the Russian ice-strengthened ship I work on seasonally in the polar regions. While this stout little vessel has undergone plenty of remodelling to bring it into line with 2016 adventure travel, it still retains relics of its 1980s charm from its cold war days as a hydrographic research and “listening” ship. This vintage phone, used for daily communications throughout the ship, sits on Chief Engineer’s desk and is still going strong. Nazdarovya!

Filed under: Image of the week, Uncategorized Tagged: adventure travel, Aurora Expeditions, Polar Pioneer, vintage phone

Fiction, Voice and Vision for Great Nonfiction

A great blog offering tips to writers via Marsha at Writing Companion.

Voice & Vision, Stephen J. Pyne’s book about writing nonfiction, starts with the question: Why do we write?

Voice & Vision, Stephen J. Pyne’s book about writing nonfiction, starts with the question: Why do we write?

Many unpublished writers dream of garnering fame and fortune. Pyne doesn’t think these aims provide a practical impetus for writing. He suggests that the genuine triggers for writing include our desire to connect with readers by entertaining them, helping them understand a topic, or providing fulfillment.

It’s not enough to come up with a great topic. Many people can think up an idea that could be developed into a book-length manuscript. But few end up with a finished manuscript. Why?

According to Pyne, some simply don’t have time to write. I’d add that some don’t make the time for writing. Others lack the motivation, skills, or knowledge to develop their ideas in terms of a major writing project.

Even writers who succeed in creating a finished manuscript may hit a brick wall when it comes to publication. One can self-publish. But…

View original post 463 more words

Filed under: Uncategorized, Words for Writers Tagged: Writing Companion