Jake Adelstein's Blog, page 88

February 6, 2011

The last Japanese man remaining in Kazakhstan: A Kafkian tale of the plight of a Japanese POW in the Soviet Union

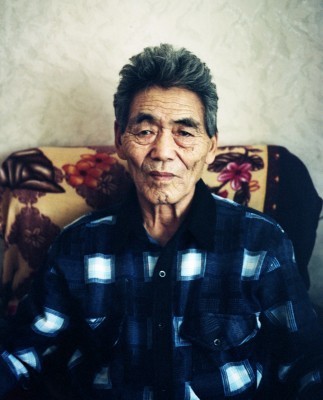

Tetsuro Ahiko photographed in his apartment Aktas, a suburb of Karaganda in central Kazakhstan on Jan. 4, 2011.

Ikuru Kuwajima, a photojournalist in Central Asia and long-time contributor to Japan Subculture Research Center, worked with Richard Orange on this fascinating piece about one Japanese POW trapped in the Soviet Union after the end of the Second World War. It differs slightly from our usual subject matter but it's a fascinating story that we hope you'll enjoy.

By Richard Orange and Ikuru Kuwajima, photos by Ikuru Kuwajima

Tetsuro Ahiko has his eyes closed now. The vodka has begun to affect him, and he rocks a little towards the battered cassette player from where the music―a shrill chorus of young girls' voices―is coming. He starts to sing along under his breath: "Shoulder to shoulder, I walk to school with my brother, thanks to the soldiers… thanks to the soldiers that died for the nation, for the dear nation." As the last voices die away, the room, in a cramped Soviet flat in a crumbling block in a impoverised town in the middle of the icy, windswept steppes of Kazakhstan, comes back into focus. "I forgot Japanese," he says. "But I didn't forget the songs that I listened to in my childhood."

This cassette of World War II military songs, long since forgotten as part of a shameful past back in Japan, is one of the handful of tokens he keeps of a life that was snatched away from him one day in 1948, when, instead of repatriating him from his military school on Sakhalin Island, Soviet troops put Mr Ahiko on a train to the Gulag work camps. More than 60 years later, Mr Ahiko is still here.

"Now I'm the same as all the people here," he says. "I've got used to it."

Tetsuro is the last Japanese man still remaining in Kazakhstan out of the hundreds of thousands Stalin shipped to the most desolate parts of the Soviet Union, putting them to work in mines, in construction, and in factories. More than a tenth of them died due to the brutal working conditions.

"I think all the Japanese have gone back apart from me," he says. "There was one from Lake Balkhash, who went to Japan because his wife was ill, and there was also one in Almaty. I think there are no other Japanese here now."

Tetsuro's ordeal began with a clerical error. In 1948, Soviet soldiers were preparing to repatriate the Japanese citizens left stranded by their annexation of Sakhalin Island in the Russian Far East. Testuro's name was on their list, but because of a transliteration mistake, the spelling didn't match that in his papers.

"I was in prison on Sakhalin for half a year, while there was an investigation," he says. "They beat us, and people wanted to get some information from me, but I couldn't speak, I couldn't speak Russian, so I didn't answer. Afterwards, I was sentenced to 10 years of prison and I was sent here. It took about one year, the whole journey."

On the train, a group of older prisoners called him over to them, pretending to befriend him. But when he left his seat, one jumped into his place and stole his mattress and all his clothes, leaving him to shiver through the rest of the journey, without even an overcoat. On arrival in Kazakstan, he spent a month near the city of Pavlodar waiting to be sent to the camps. There were more than 60 prisoners, he remembers, crammed into a tiny hut whose broken windows did little to keep out the icy cold.

"It was impossible even to move, or even to lie down to sleep. You could only sit. I was almost naked, even in January," he says. "One person looked at me, and brought from somewhere a t-shirt. I still remember it. It was so dirty that it seemed like it was made of leather."

Then the orders came. He was to work in the copper mines in Jezkazgan. He was just sixteen.

"We were young and healthy, but after working three months in the ore mine in Jezkazgan, we were not healthy any more," Tetsuro remembers. "After that I was sent to Spassk. It was the camp where they sent people who were almost dead. The logo was 'today you will die, and tomorrow I will'."

Many of Tetsuro's fellow prisoners were Japanese, but there was little camaraderie. "We didn't speak to each other; we just thought, 'I want to eat, I want to eat'. That's what I was repeating in my head all the time. I was just thinking 'I want to go home, I want to go home.' "

But unlike almost all the other Japanese in the camps, when Tetsuro was finally released in 1954, he did not go back to Japan. "The administrators of Karlag [the Kazakh camp system] maybe mistyped, or made a mistake, in the list of prisoners in Karaganda," says Shunsuki Ajikata, a former employee of Japan Sakhalin Compatriot Exchange Association, which tracks down Japanese still stranded after Russia's annexation of Sakhalin.

By 1956, when the Soviet Union made its last major repatriation to Japan, it had sent 510,000 prisoners home. But Tetsuro was not among them. Classed as a political prisoner, he had to report to the police in Aktas every three months. He was not given proper papers, which meant he was barred from official employment.

"There were free rooms at the military base, so I slept there on the floor. I didn't have any clothes besides what I wore at the camp, and I slept in my clothes. I didn't have money to buy food." He survived on scraps from a miners' canteen. "I couldn't go there during the day because there were too many people, so at midnight I collected their leftovers. I'd bring all that back home, sit down and eat."

Eventually, Tetsuro did find work, as a labourer in a cement factory. There he met Katya, an ethnic German born in the Russian city of Saratov, who he married, taking on her two young children. Shortly after in 1959, Tetsuro's father, who had learned his whereabouts from returned prisoners, managed to get a letter to him, asking him to leave everything and come back to Japan. It's unclear whether Tetsuro's status as a political prisoner would have allowed him to go. He refused either way.

"Katya was worrying, crying, afraid I would leave for Japan," he remembers. "But I didn't want to go. I wrote back to my father that I was abandoned by my family in 1945, was hungry, cold and lonely, but survived, was arrested in 1948 and sent to Karlag. I couldn't leave my children and wife and risk them repeating my destiny. My father was offended and didn't write to me again."

His younger brother Yujo later told him: "When father received your letter, he grew very old at once."

After that, Tetsuro had no contact with home for a further 37 years. It was only in 1993, in the thaw following the collapse of Soviet Union, that the Japan Sakhalin Compatriot Association managed to track him down. The following year, 46 years after he first boarded the train to the Gulag, the association flew him to Japan to meet his brothers and sisters, who lived in the city of Sapporo on Japan's most northerly island.

"I'd absolutely forgotten the language, I had to have an interpreter," Tetsuro remembers. He pulls out an old album of photos from the visit, and shows a picture of him sipping tea from a bowl, sitting cross legged next to his brother, both of them dressed in ceremonial Japanese clothing, and another with his sisters sipping beer and eating sushi. His father had since died.

In 1996 he went a second time, this time with his daughter Irina, and it was then that the Japan Sakhalin Compatriot Exchange Association made an offer to bring Tetsuro back to Japan. The offer was generous. The family would get all travel expenses, six months' training in Japanese language and culture at a special facility north of Tokyo, a flat in Hokkaido, and a monthly pension. But Tetsuro turned it down.

The standard of life in Aktas is low, even for Kazakhstan. The average monthly salary sits well below the $500 a month average for the country, and the town, with its crumbling blocks and dusty, pot-holed streets, has seen few benefits from Kazakhstan's recent economic growth. The climate is harsh. Winter temperatures frequently dip below -30℃. The only features that break up the surrounding treeless steppe are a sprinkling of mines, and giant Soviet era industrial plants, belching smoke into the air.

But Tetsuro has made his home here. In 1993, he had just retired, and was looking forward to taking fishing trips to the lakes and rivers nearby, And anyway, he didn't want to live off charity. "If I went to Japan, I would be living on a government allowance as if I was a beggar," he says. "But here, I have earned my pension. I don't want money from strangers."

Last summer, the association again offered to resettle him, his Russian wife Elena, one of his children, and their family. Again he refused, this time because he didn't want to leave any of his family behind. Tetsuro has several grandchildren now, from both his daughter, Irina, who is married to a Russian, and his son Teruo, who recently divorced his Ukrainian wife. And the Japan Sakhalin Compatriot Exchange Association is only prepared to resettle one child and one set of grandchildren.

But as Tetsuro approaches 80 years old, it's clear he yearns to end his days among his own people. "If the children knew Japanese, probably we could go there," he sighs, when I press him on the subject. His Russian second wife, Elena, looks at me with increasing suspicion, and when I ring back after my visit to clarify aspects of his story, his daughter Irina begs me to leave them alone.

"Please don't call any more," she asks. "Every time he speaks to you about this, he is upset for days afterwards." So for now Tetsuro is left to rely the cheap Japanese souvenirs he has brought back from his trips home: a plastic doll in a kimono, some wall hangings of Japanese calligraphy, a few ornate plates and bowls, and his cassette of old war songs.

That, and the one aspect of Japanese culture he has always carried with him. "I still bow," he says with a dry laugh. "From the first time I came here, I would always do it, even to the people who were working in the camps. I would go and take a bow."

Marina Gorobevskaya contributed to this article.

Ahiko-san photographed in his apartment

The entrance of Ahiko-san's apartment in Aktas, Karaganda. The temperature often reaches minus 30 degrees Celsius in the area. Ahiko-san said he gets outside only a few times a month during the winter because of the cold.

Ahiko-san's wife Elena

[image error]Vodka bottle thrown away on the street of Aktas

February 3, 2011

How to speak dramatic death and destruction: yakuza lingo

Film buffs and Japanophiles delight: The Japan Times ran a great article by film reviewer Mark Schilling about lines in various yakuza flicks, using some solid classics like the Jingi series and Tokyo Drifter as fuel:

Another immortal Takakura line was one he delivered just before he and Ryo Ikebe were about to 殴りこみ(nagurikomi, invade the headquarters of a rival gang) in Kosaku Yamashita's 「緋牡丹博徒」 ("Hibotan Bakuto," "Red Peony Gambler," 1968): 「所詮、俺達の行く先は赤い着物か、白い着物」 ("Shosen, oretachi no ikusaki wa akai kimono ka, shiroi kimono ka"; "After all, we're bound for either a red kimono [worn by prisoners] or a white kimono [worn by the dead].")

This stoic view of life extended to affairs of the heart. In Seijun Suzuki's 「東京流れ者」 ("Tokyo Nagaremono," "Tokyo Drifter," 1966), Tetsuya Watari, whose character has become a hunted outcast after killing his duplicitous boss, must say farewell to his nightclub singer girlfriend, played by Chieko Matsubara. Before departing, he tells her 「流れ者に女はいらない、女がいちゃ歩けない」 ("Nagaremono ni onna wa iranai, onna ga icha arukenai"; "A drifter doesn't need a woman. If a woman's around he can't walk").

Read the full article here.

Besides being awesome, yakuza films are, like mafia movies, massively important in defining how the Tanaka Taros imagine their country's underbelly–right down to the trill of growled Hiroshima-ben. While there's not a huge opportunity to fit something like "死んでもらいます" (shinde moraimasu–"I want you dead") into a chat with the local combini staff, it makes for great party chit chat… amongst your yakuza movie-obsessed friends. Or if anyone's in the NYC area during March and wants to try out a few lines on Jake at the Onibi screening, I'm sure he'd appreciate it.

Also, don't forget to check out our growing Yakuza Dictionary, and make your own suggestions!

February 1, 2011

Sumo Wrestlers Fixed Matches, But Who Gave The Orders?

Japanese police sources are saying that there is evidence sumo wrestlers contacted each other via cell-phone to fix sumo matches in advance. AFP has an excellent piece on the recent developments. The Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department Organized Crime Control Division has been aware of contacts, collusion, corruption and betting between members of the Yamaguchi-gumi organized crime group and sumo wrestlers since 2008, but only really began investigating the links in September of 2009. The actual investigation is grinding to a halt with the arrest of a few key figures. At present, it seem unlikely that the police will press charges against any sumo members for throwing matches or fixing the outcomes of various bouts. It is unclear why the wrestlers threw matches or who gave them the orders to do so.

In a way, it's kind of vindicating to see the investigation turn out as I expected it would and a little disappointing. In this interview with AP in July of 2010, I expounded as succinctly as possible on the problems with yakuza and the sumo world.

"Sumo is involved in organized crime because they've had a symbiotic relationship for years," said Jake Adelstein, a former crime beat reporter for a Japanese newspaper and author of the best-selling book "Tokyo Vice." "The wrestlers and the yakuza have a macho admiration for each other. The yakuza by being seen with the sumo wrestlers, acquire 'status' and the sumo wrestlers get money, booze, food, and women."

Adelstein said smaller training stables don't have big corporate sponsors and need the money the yakuza offer. "The average salary of a sumo wrestler is a pittance and they need the cash," he said, adding that once a wrestler is beholden to the mob he is vulnerable to demands to throw bouts — which the gangsters bet on — to clear his debt."

In the best of worlds, the sumo baseball betting scandal would be pursued until it was proven that yakuza had also been involved in match-rigging as well. Perhaps the latest judicious leak from the police is an attempt to garner public outcry so that they can pursue the investigation even farther. However, if I was going to bet on the outcome, which I would never do, since gambling is a crime in Japan–I'd bet that the investigation ends with a few arrests and a post-humous prosecution of the yakuza boss who was believed to have organized a great deal of the betting.

I wouldn't mind losing the hypothetical bet, though.

January 30, 2011

Event: Yakuza fiction vs fact at the New York Japan Society

For those in the New York area, Jake Adelstein will be appearing at the Japan Society's event, "Yakuza in Popular Media & Real Life: Cracks & Chasms", on March 10 at 6:30pm.

From popular films to games and comic books, yakuza culture has been portrayed and discussed in many media. Jake Adelstein, author of Tokyo Vice–one of the rare books revealing real yakuza culture in Japan–discusses the differences between the image the yakuza want to project and how the major groups really function, and what the taboos are of depicting yakuza in Japan.

Followed by the film:

Onibi–The Fire Within

Thurs., Mar. 10 at 8:15 pm

Often regarded as Rokuro Mochizuki's masterpiece, Onibi injects both sexual passion and subdued sentiment into the macho world of yakuza cinema. Jake Adelstein introduces the film.

Check out the Web site for more details, and keep an eye out for ticket information! Looking forward to seeing some JSRC readers there!

January 29, 2011

In Tokyo, Komatsu-gumi head arrested for extortion; Yamaguchi Kodo-kai Nearing Decimation

Police arrested the head of the Yamaguchi-gumi Kodo-kai-affiliated Komatsu-gumi on January 29 under suspicion of attempted blackmail after he reportedly tried to extort money out of a company executive. Police also raided the organisation's office. It was another major blow to the Kodo-kai who has seen their numbers cut significantly in the last year and four months. The mass arrests of organization members and crackdowns on affiliated entities has made many leave the group and supporters pull back.

According to police, 56-year-old Kazuo Shiina holds executive ranking within the Kodo-kai, an organisation central to the giant Yamaguchi-gumi, and is in charge of the Tokyo area. Authorities say Shiina tried to twice extort a Saitama-based company executive out of 50 million yen after the man couldn't pay back a loan from the organization.

Other senior members of the Yamaguchi-gumi Kodokai in Tokyo have been arrested in the last few weeks. The organization itself has dwindled from 4,000 down to nearly a 1,000 after an extensive crackdown by the National Police Agency which began in September of 2009 under the direction of National Police Agency chief, Ando Takaharu.

On January 26th, the National Police Agency (NPA) held a meeting of all organized crime control bureau chiefs from police departments in Japan. He ordered each division chief to devote their efforts to not only arresting and dismantling the Kodo-kai but to cracking down on all front companies of the go organization and any cooperative entities (共生者・kyoseisha). The goal is to drive the group into extinction by cutting off their funding and distancing them from other revenue sources. It is rare for the NPA to not only target one organized crime group for demolition but also to direct the police to aggressively crackdown on corporations and small companies associated with the group.

One of the primary reasons the NPA has been cracking down on the Kodo-kai since September 30th of 2009 is that the group is openly hostile to the police, even threatening officers and that the faction has made huge incursions into the financial and business world, shaking the foundations of the Japanese economy and public faith in the stock market. In 2007, a former Kodo-kai member, backed by the organization, even took control of a major social networking site with a membership of over a million followers, creating a minor panic about internet security and organized crime attempts to corner personal information for criminal purposes.

The symbol of the much feared Yamaguchi-gumi Kodo-kai, the ruling faction of Japan's largest organized crime group.

The symbol of the much feared Yamaguchi-gumi Kodo-kai, the ruling faction of Japan's largest organized crime group. Chief Ando opened the meeting by stating, "Japanese society is coming together to get rid of organized crime. This is a one in a thousand chance to weaken the Kodo-kai and thus the Yamaguchi-gumi, and destroy their organization."

Read the original article about the arrest here. Note: Assistant editor, Jake Adelstein, also contributed to this article.

January 22, 2011

In Battle For King of the Bugs: Saw Beetle Kicks Miyama Beetle Butt New Research Reveals; SEGA Silent on Video Game Repercussions

Nobody expects realism in video games but someday they might. The popular King of Bugs (ムシキング) video games series is one in which players select their bug and fight off arthropod opponents to see who can knock the other out of the ring first. You can play against the computer or you can play against a friend. Real life bug matches between stag beetles (鍬形虫/kuwagatamushi) were a popular games for children in the day before video games and when Japan still hadn't managed to decimate it's natural environment. Generally speaking, when it came to stag beetles, it was thought that all beetles had pretty much the same chance. Well, apparently that's not the case. And that could have serious repercussions on the pereived accuracy of this gaming classic. (No plans have been announced to revise the board game version or issue a recall.)

Questions have been raised as the accuracy of the Japanese Saw Stag Beetle depiction in the popular King of Bugs (ムシキング)series. Will future editions reflect recent scientific findings?

According the January 18th, 2011 edition of the Asahi Elementary School Newspaper (朝日小学生新聞), Yoshihito Hongo (本郷儀人研究員)a researcher at Kyoto University Graduate School– the Japanese Saw Stag Beetle (ノコギリクワガタ/nokogirikuwagata)is much more likely to win over the Miyama Japanese Stag Beetle in an even fight. This is surprising when you consider that the average Saw Beetle (3.8 centimenter) is smaller than the Miyama Beetle (4.1 centimeters). The secret: the Saw Beetle's devestating underhand throw (下手投げ/shitatenage). The two male beetles often fight over women and food.

Hongo-san who was an old school stag beetle fan noticed that in the Kyoto area that the number of Saw Beetles seemed to be growing in recent years. In 2008, he began to study why. After extensive experimentation and fairly staged fights, he was able to determine that out of 224 battles the Saw Beetle won 145 fights and the Miyama Beetle only 99 fights. In most cases, the deciding factor was the underhand throw. The Saw Beetle would crawl under the Miyama Beetle, sandwiching it between its huge jaws and then and toss it into the air, off the playing grid. The Saw Beetle was also able to perform an effective overhand throw as well.

Researcher Hongo's conclusion: "The Miyama Beetle may be bigger and better looking but it's all show. When it comes down to it, the underdog wins in this case." At the time of publication of this article, Sega was unavailable for comment on to whether future editions of the Mushi King series would reflect the latest scientific data which should techinically give players who chose the Saw Beetle an advantage in fights with Miyama Beetles, especially if they utilize the underhand throwing sequence. Memo: I seriously doubt SEGA will even answer my inquiry on this one but can't hurt to ask.

Bet on the Japanese Saw Stag Beetle!

In Battle For King of the Bugs: Saw Beetle Kicks Miyama Beetle Ass New Research Reveals; SEGA Silent on Video Game Repercussions

Nobody expects realism in video games but someday they might. The popular King of Bugs (ムシキング) video games series is one in which players select their bug and fight off arthropod opponents to see who can knock the other out of the ring first. You can play against the computer or you can play against a friend. Real life bug matches between stag beetles (鍬形虫/kuwagatamushi) were a popular games for children in the day before video games and when Japan still hadn't managed to decimate it's natural environment. Generally speaking, when it came to stag beetles, it was thought that all beetles had pretty much the same chance. Well, apparently that's not the case. And that could have serious repercussions on the pereived accuracy of this gaming classic. (No plans have been announced to revise the board game version or issue a recall.)

Questions have been raised as the accuracy of the Japanese Saw Stag Beetle depiction in the popular King of Bugs (ムシキング)series. Will future editions reflect recent scientific findings?

According the January 18th, 2011 edition of the Asahi Elementary School Newspaper (朝日小学生新聞), Yoshihito Hongo (本郷儀人研究員)a researcher at Kyoto University Graduate School– the Saw Japanese Stag Beetle (ノコギリクワガタ/nokogirikuwagata)is much more likely to win over the Miyama Japanese Stag Beetle in an even fight. This is surprising when you consider that the average Saw Beetle (3.8 centimenter) is smaller than the Miyama Beetle (4.1 centimeters). The secret: the Saw Beetle's devestating underhand throw (下手投げ/shitatenage). The two male beetles often fight over women and food.

Hongo-san who was an old school stag beetle fan noticed that in the Kyoto area that the number of Saw Beetles seemed to be growing in recent years. In 2008, he began to study why. After extensive empirmentation and fairly staged fights, he was able to determine that out of 224 battles the Saw Beetle won 145 fights and the Miyama Beetle only 99 fights. In most cases, the deciding factor was the underhand throw. The Saw Beetle would crawl under the Miyama Beetle, sandwiching it between it's huge jaws and then and toss it into the air, off the playing grid. The Saw Beetle was also able to perform an effective overhand throw as well.

Researcher Hongo's conclusion: "The Miyama Beetle may be bigger and better looking but it's all show. When it comes down to it, the underdog wins in this case." At the time of publication of this article, Sega was unavailable for comment on to whether future editions of the Mushi King series would reflect the latest scientific data which should techinically give players who chose the Saw Beetle an advantage in fights with Miyama Beetles. Memo: I seriously doubt SEGA will even answer my enquiry on this one but can't hurt to ask.

Bet on the Japanese Saw Stag Beetle!

January 20, 2011

Underage Japanese girls learning to sell themselves online

The plague of child porn has in recent years been facilitated by the spread Internet, writes the Yomiuri in an article sourcing our favorite Polaris Project pundit, Shihoko Fujiwara.

"One of the reasons for the increase is due to the crackdown [by authorities], but another is that a growing number of children have become involved in the business through the widespread use of the Internet," she said.

According to Fujiwara, a 14-year-old second-year female middle school student was forced to sell sexual services by her classmates and the scene was filmed by male customers.

A female student, 15, who attends a public high school, sold a nude image of herself through an Internet message board to raise money to go to university, as she is unable to depend on her parents financially. She contacted Polaris after a man who purchased the image threatened to meet her in person and another demanded she send more images.

(Full article here)

The piece goes on to explain how Web sites are providing the base for a new kind of enjo kosai-esque self-exploitation, allowing teenagers to receive money for posting nude photos of themselves according to customer demands. As with many online trends in Japan, the child pornography is often shot and distributed via mobile phone, making it difficult for parents to discover what's happening.

The typical image of child pornography is that of the vile act of photographing juveniles in sexual situations either against their will or unbeknown to them, but in this case kids are often voluntarily participating in the system. While there's much spoken about laws in the article, when children are willing to victimize themselves for money, there needs to be effort put into prevention on both sides.

January 16, 2011

Tokyo LGBT community and supporters protest Ishihara's homophobic comments

By Mizue Watanabe

Tokyo's LGBT community and its supporters held a lecture event January 14 to address the homophobic statements made in early December by Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara. The two-part event saw politicians, LGBT activists, and even an openly gay manga artist speak to an audience of over 350 people, the majority of which were Japanese.

The meeting was held in reaction to comments made by Ishihara December 3 during a statement regarding a bill to put more stringent regulations on anime and manga. He said that "Homosexuals have been appearing on television as if it were no big deal. Japan is becoming too unregulated." When a journalist from the Mainichi Shimbun asked Ishihara for clarification on these comments on December 7, Ishihara elaborated: "I feel that [homosexuals] are missing something. Maybe it has something to do with their genes. I feel sorry for them as a minority." Recalling his experience observing a gay pride parade in San Francisco, Ishihara added that, "I saw the pride parade, but I just felt sorry for them. There were male pairs and female pairs, but I felt that something was missing."

Perhaps reflecting the peripherality of LGBT issues in mainstream consciousness, only the Mainichi, the Asahi Shimbun, and the Tokyo Shimbun reported these comments.

The Association to Protest Governor Ishihara's Homophobic Comments hosted the lecture event as a protest against the governor's discriminatory remarks as well as a show of solidarity among the LGBT community and its supporters. The first part of the event featured a panel discussion of LGBT activists and community advocates discussing their reactions to the governor's comments. This was followed by informal statements by three municipal politicians, including Aya Kamikaya, an assemblyperson for Tokyo's Setagaya ward and the first openly transgender politician to be elected in Japan. The second part of the event focused on some of the daily struggles of the LGBT community in Japan, and featured manga artist Taiji Utaguwa's rendition of recent gay history as well as a "close talk" with two gay couples.

Although serious in nature, the event involved light-hearted moments as well, such as when the opening discussant unleashed two giant balloon balls reading Ishiharasumento-kin ("Ishiharassment" Germ) into the audience. "Please be careful everyone, they're highly infectious!!" she yelled, to the audience's delight. Many of the participants, however, spoke of their serious concern with the governor's comments, noting their distress that these comments were being made from the governor of Japan's largest and most cosmopolitan city. One activist compared Tokyo to Paris and Berlin, which both have openly gay mayors.

A common sentiment among participants was that Ishihara's statements make light of the difficulties that many LGBT individuals struggle with in their day-to-day lives, including within the home, at school, and in the workplace.

Although a date has not yet been set, an event organizer announced that the protest against Governor Ishihara's statements would continue with a public demonstration scheduled for March.

Ironically, Ishihara's remarks came during Human Rights Awareness Week in Japan, held annually from December 4 to December 10. Activists have pointed out that although the Tokyo Metropolitan Government had listed "eliminating discrimination based on sexual orientation" and "eliminating discrimination based on gender identity disorder" as two official goals, the comments by Tokyo's highest elected official make a joke of this.

Since his election as governor of Tokyo in 2001, Governor Ishihara has become notorious in the domestic and international press for a string of disparaging comments, attacking women, the disabled, foreigners, and even – perhaps most bizarrely – the French language.

In May 2001, when addressing the issue of crimes committed by non-Japanese residents of Japan, Ishihara suggested that, "Foreigners have criminal DNA." However, despite Ishihara's tendency to couch his prejudicial views within "biological" terms, neither of these comments is known to have any scientific validity.

January 12, 2011

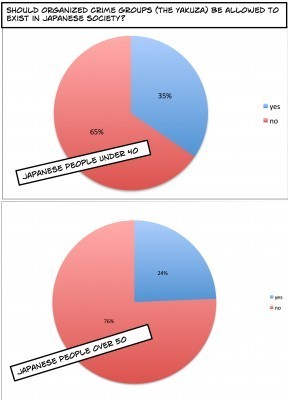

One in 10 under 40 consider the yakuza "A neccessary evil" in Japan

Younger Japanese appear less likely to regard the yakuza as a menace, and one in ten of them consider Japan's organized crime groups to be a necessary evil, a recent study revealed. The Nara Prefecture Police Department, working with the local government as part of their efforts to enact an effective "Organized Crime Exclusionary Ordinance", issued a questionnaire in October 2010 to gauge current attitudes towards organized crime. The results, which were published this week, indicate that younger Nara residents have a weaker sense of danger concerning the yakuza than middle-aged or elderly residents.

Residents who visited the Nara driver license center were asked to participate; 1086 responded. To the question "What do you think of organized crime?", 75 percent of those over 50 choose the response, "They are anti-social groups which society should not allow to exist." Only 35 percent of those under 40 chose the same response.

Only 3 percent of those over 50 would say that "The existence of the yakuza is not a bad thing" or "The existence of the yakuza is a necessary evil," while 13 percent of the younger group agreed with these statements.

With the statement, "The existence of the yakuza makes me uneasy," 57 percent of the older group agreed, as opposed to only 37 percent of the younger group.

The Nara Police Department Organized Crime Control Division 2 speculates that there are many young people who are unaware of the way the yakuza actually operate in society. The goal of the ordinance is to shut out organized crime from society, and the police have said they will continue to work hard to make this an effective ordinance.

The idea that the yakuza are "a necessary evil" is not a new one in Japan. Even some police officers also quietly espouse the theory, arguing that the only thing worse than organized crime would be disorganized crime. Books like Necessary Evil, by a corrupt ex-prosecutor, and the yakuza fan magazines all expound on the theme that yakuza are an integral part of Japan's public safety. Apparently, a surprising number of ordinary citizens believe this as well, but the older the citizen is the less likely he or she is to consider them (the yakuza) acceptable any longer. It's not clear what is the cause of the discrepancy.

1 in 10 Japanese People Under 40 Feel The Yakuza Are A Necessary Evil