Shelina Zahra Janmohamed's Blog, page 10

July 31, 2012

BBC Radio 2 Pause for Thought 18 July: Ramadan and Discipline

I was broadcast on BBC Radio 2’s Pause for Thought Segment on the Vanessa Feltz show. Here’s the text of the broadcast

It’s the beginning of Ramadan this week, the Islamic month of fasting, where Muslims refrain from bodily intake from dawn to dusk. I’ve hung my timetable on the wall which indicates for each day of the month, the exact minute when morning breaks and when night falls, the minutes which mark the boundaries of the fast.

In these longer days of the British summer when the day starts as early as 230, and night does not set till well after 9pm, fasting is no mean feat.

The rigid discipline feels unmanageable – it’s just not normal to refuse all food and water for nearly twenty hours. It’s the morning coffee I miss most, that, and the pleasure of tasting flavours and food.

But you get used to it surprisingly quickly, usually within a few days, and the discipline yields some surprising results. Your body stops dominating how you structure your day because huge swathes of time are freed up from preparing and consuming breakfast and lunch. Instead of thinking about your body all the time, you can think about you.

The discipline extends to cutting out gossip and what you come to realise is pointless chatter – admittedly guilty pleasures. Again it’s surprising how much time this frees up for self-reflection and resolutions, and actually getting round to do the things you always meant to do. It’s like new year, but you have a whole month ahead of you with a vast community of nearly two billion people all pulling in the same direction during which to embed your resolutions.

Almost exactly as Muslims are participating in Ramadan, and all the physical, mental and spiritual focus that requires, the Olympics will be taking place in London. For these athletes, discipline is a way of life, a means towards achieving their dreams. The structure, rigour and absolute commitment towards their goals will reach a culmination during these three weeks.

Discipline, rules and structure are unfashionable these days, seen as being repressive. But our celebration of events like the Olympics should make us stop and think about the fact that discipline is quite the opposite of constraint: instead discipline releases our potential. Of course upholding discipline in our lives is tough, but if we want to see the potential it can liberate, all we need to do is to watch the incredible achievements of the Olympians over the coming weeks.

July 21, 2012

Romeo and Juliet in Baghdad review – what can Iraq learn from Shakespeare?

This article was published this week by Common Ground News Service.

London – As part of the 2012 Summer Olympics hosted in London, the Royal Shakespeare Company challenged theatre groups around the world to create contemporary re-imaginings of 16th century playwright William Shakespeare’s classics. Of the many unique and creative performances, Romeo and Juliet in Baghdad, performed by the Iraqi Theatre Company, caught my eye. Could one of Europe’s greatest romantic tragedies, written in the 16th century, tell us something about Iraq in the 21st century?

Adapted into colloquial Arabic, and performed by an Iraqi cast with English surtitles above the stage, the story, while written in an Iraqi context, is a familiar one. The story opens with two brothers, Montague and Capulet, who have feuded for nine years over who will steer their family’s pearl-diving ship. This serves as an apropos metaphor for Iraq at the beginning of the war. Romeo and Juliet, who like all the play’s characters retain their original Shakespearean names, have already met and fallen in love before the feud. They have been kept apart by the cycle of violence resulting from the feud between their fathers.

Adapted into colloquial Arabic, and performed by an Iraqi cast with English surtitles above the stage, the story, while written in an Iraqi context, is a familiar one. The story opens with two brothers, Montague and Capulet, who have feuded for nine years over who will steer their family’s pearl-diving ship. This serves as an apropos metaphor for Iraq at the beginning of the war. Romeo and Juliet, who like all the play’s characters retain their original Shakespearean names, have already met and fallen in love before the feud. They have been kept apart by the cycle of violence resulting from the feud between their fathers.

The play focuses less on their romance and more on how families, communities and nations can easily and quickly be torn apart. The story prompts the audience to reflect on how pride, regret, a lack of mutual understanding and interference from the outside are obstacles to resolving conflicts peacefully. Once blood has been spilt, we are never sure if peace can be restored.

The play’s director, Monadhil Daood, fled Iraq in his 20s after staging a play under Saddam Hussein about the Iran-Iraq war. In 2008, he founded the Iraqi Theatre Company to “bring a contemporary cultural voice of unity and inclusiveness into the civic discourse in Iraq”. Monadhil says that “I think my [play] ‘Romeo and Juliet in Baghdad’ will be a mirror. The audience will see themselves on the stage.”

In the buzzing auditorium, I saw his prediction come true. The emotional effect the play had on its audience was clear. During the performance, many had eyes filled with tears. At joyous moments, audience members tapped along to the wedding songs and laughed at the inclusion of an old Iraqi folk story about a beetle looking for love.

During the most emotional moment of all, I felt almost swept off my chair at the audience’s roar of approval as the imposter, who was betrothed to Juliet against her will, and who had stoked the tension between the two families, was cast out by Juliet’s father, Capulet. This character, a miserable hardliner, represents the presence of al-Qaeda in Iraq. Through Capulet’s action, the betrothal is reversed and his presence is no longer accepted.

The real story of Romeo and Juliet in Baghdad is of the audience, who see their lives played out before their eyes. The drama was an opportunity to create enough distance from their own stories so that they could look at the effect of the last nine years on their homeland, with its immense loss, death and suffering. It was an opportunity to move on, make sense, find catharsis and even laugh.

The play at its heart is a universal story of the birth and development of conflict, stoked by fear, misunderstanding and pride. It shows how outside forces can stoke conflict and divide groups of people, and reflects on the need for unity.

In this case, a love story is a portal into a world that audiences might otherwise never be able to begin to understand. By connecting with the story of young lovers – a theme that transcends time and culture – we can learn about the nuances of today’s Iraqi society. The play helps viewers understand tight knit family structures and the once strong historic relationships between Sunni and Shia Muslims that are now being broken down. In fact, people around the world might find a lot in common with the ordinary folk of Iraq and their aspirations to bring an end to violence and live better lives.

But more importantly, through such plays, we are confronted with universal truths: conflict persists across human societies and it must be addressed before it spirals out of control. But most of all, the aspiration to love and be loved is present in all times and places, whether in Baghdad or Verona, for lovers like Romeo and Juliet, or for brothers like Montague and Capulet.

June 9, 2012

Satyamev Jayate, Aamir Khan and changing the culture of shame

This is my weekly column ‘Her Say’ for The National newspaper in the UAE

I’m a little bit in love with Aamir Khan. The Bollywood superstar might have fans around the world swooning at his film appearances, but I’ve only just fallen for his charms after the launch of his new TV show, Satyamev Jayate – Truth Alone Prevails.

It’s a 13-part series airing in prime time on Sunday mornings across both private and public networks in India. I admire Khan’s aspiration: he sees the problems in his own society and wishes to make a change from within.

It’s a 13-part series airing in prime time on Sunday mornings across both private and public networks in India. I admire Khan’s aspiration: he sees the problems in his own society and wishes to make a change from within.

The format – chat-show-meets-investigative-journalism news magazine – excels at tackling issues that are considered taboo. So far Khan has covered the horrors of widespread female foeticide, child sexual abuse, dowries, medical malpractice and honour killings, issues that rarely receive enough scrutiny.

I’m impressed that Khan is using his celebrity to address publicly issues that usually bubble under the surface, and are considered shameful to talk about. He’s been criticised for commercialising the subjects, taking a large fee for his work and for the high price of the advertising slots. But the financial side of the show gives him leverage to delve into subjects few others do.

And the show’s reach has been remarkable. The launch episode is estimated to have been watched by more than 90 million viewers, and the programme’s social media strategy means that the debates each episode raises are being continued off air.

Even governments have been forced to act on the show’s recommendations. Following the discussion on female foeticide, which aired at the beginning of May, authorities in Rajasthan immediately ordered an investigation into doctors and clinics believed to be conducting the illegal and disgusting procedures.

Three of the five episodes so far have focused on abuse against women, although the subjects of child sexual abuse and medical malpractice are not gender specific. But societal pressures suggest women are supposed to just tolerate abuse, because to stand against the system brings shame on themselves, and their families. The threat of being the source of shame for the family is particularly powerful as it can destroy a family’s reputation for generations. The shame follows them for the rest of their lives, and is often felt to be a worse fate than the abuse itself.

Sadly, women themselves perpetuate abuse when they buy into this myth, trapped in the circle of shame and oppression.

Shame is one of the most powerful tools of social control, especially against women, whose reputation is their main social capital. That is why those who come onto Khan’s show to talk about their experiences in the full glare of the public eye are the real heroes. These women break open the shackles of shame, making other victims realise that the abuse they are facing is not acceptable, and that they too can speak out.

The shocked faces of the audience, and the blanket coverage of the show in India’s press as each issue is addressed, makes it clear that people know where the rot lies. But it is the public nature of the conversation that is the trigger to creating change, and this is facilitated by Khan’s celebrity status.

His star power allows him to raise subjects in ways that make people listen, and although it shouldn’t be like this, the fact he is a man in a society where men’s opinions are perceived to hold more value adds to his influence.

Those who have privilege and authority at their disposal, as Khan does, must give a hand to those who have neither. If they do not, then they are negligent. If they perpetuate such abuse, whether male or female, then they are culpable.

May 12, 2012

The Olympics are coming to London: along with traffic, warzones and pandemics. No wonder I feel grumpy

My weekly newspaper column for The National published today.

The Olympics are almost upon us. The correct response should be “Hurrah!” but that’s not how I feel at all. I am unexcited, despondent and frankly just a teeny bit scared.

Last weekend, 40,000 people attended an opening ceremony at Olympic Stadium, where the Games will begin on July 27. The day before the weekend event, a newspaper smuggled a fake bomb into the Olympic site.

Last weekend, 40,000 people attended an opening ceremony at Olympic Stadium, where the Games will begin on July 27. The day before the weekend event, a newspaper smuggled a fake bomb into the Olympic site.

I was driving past the stadium going to a wedding, and through the gaps in the glorious infrastructure I glimpsed London’s beautiful people assembled to mark the formal opening.

While rubbernecking the crowd I had to screech to a halt because of traffic congestion. Not hurrah.

It’s not just Olympic traffic that bothers me. London is being turned into a war zone. This week, fighter jets flew low above my suburban home, so close that the floors started vibrating and my baby started crying. And missiles are being placed on the roofs of urban buildings.

Even with more than two months to go, London is morphing into a different kind of city, and I don’t like it one bit.

Worse, I don’t like not liking it. I believe I ought to feel ecstatic, as though Harry Potter, the Tooth Fairy and Elvis Presley were all gathering for a never-before-never-again magic joy-fest.

When London won the bid to host these Olympics, we were told we would have to pick up the cost, estimated at Dh33bn, or, as it was described to us, “the cost of a Walnut Whip a day”. This refers to a small, wrapped chocolate costing about Dh3. Now, seven years and 2,500 imaginary Walnut Whips later, I feel short-changed and miserable.

It’s probably the Brit in me that makes me pessimistic about potentially good things, makes me expect failure. For example, compared to the spectacular Beijing Olympics – in which all one billion Chinese seemed to take part in a perfectly choreographed ceremony – our failure can be nothing but utterly dismal.

And if fighter jets, missiles and fake bombs weren’t enough, the crowds might kill us.

With a joyful melange of the global population gathering in one small space from all the world’s infected backwaters, London is at risk of hosting a global pandemic: the black death meets Sars meets I Am Legend. And we won’t even be able to get away, because there will be just too much traffic.

So I will be languishing in my London living room this August; I won’t get the chance to be an actual part of the Olympics. Just as if the Olympics were in Beijing or Barcelona, I will be watching them on television.

But I will be all the more despondent, grumpy even, because I have paid for them, and because even though I applied for tickets, I didn’t get any.

For Muslims, about the only bright side of London as a commercial city shutting down is that the Olympics and Ramadan coincide. So many Muslims will be able to work from home during the long fasts, rather than commuting into muggy crowded London in the summer heat.

Actually, though, for the price of a Walnut Whip every day for seven years, I could have bought myself a month on a paradise island with no crowded trains, no fighter jets and little risk of deadly viruses.

And I still could have enjoyed watching the Olympics on television.

May 11, 2012

Stop this drip feed of hatred in Europe

A little belatedly, one of my ‘Her Say‘ columns for The National newspaper

Europe is once again in confusion over how to deal with European Muslims.

In Germany, a small Muslim group, identified as extreme Salafi by the government, wants to distribute 25 million free copies of the Quran in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. The authorities believe the Quran campaign is a cover for jihadist recruitment. The leader of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s parliamentary group “strongly condemns” the campaign.

In Germany, a small Muslim group, identified as extreme Salafi by the government, wants to distribute 25 million free copies of the Quran in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. The authorities believe the Quran campaign is a cover for jihadist recruitment. The leader of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s parliamentary group “strongly condemns” the campaign.

Equating free Qurans with recruitment for terrorism is a rather surprising leap. The campaign and the Quran’s contents are hardly covert. Billions of Muslims around the world read the Quran and lead unexciting, peaceful and boldly un-jihadist lifestyles, and giving out free Qurans is an entirely legal activity in Germany.

Politicians have conflated those whom they believe are engaging in extremist activities with the core platform of Islam. Rightly, there are no governments in Europe that “strongly condemn” the millions of Bibles that are given away, or the organisations that leave them in hotel rooms. Condemning free Qurans is just another manifestation of the misguided and downright dangerous idea that absolutely anything to do with Islam is a step on the road to terrorism. Such incidents add up to a wider, corrosive atmosphere of hatred.

We can see this in the case of Anders Behring Breivik, on trial in Norway this week, who claims that his actions, which resulted in the deaths of 77 people, were “self-defence”.

It’s hard not to see a man who is filled with hatred built up of these seemingly tiny and innocuous negative conflations. His ocean of hatred is being painted as belonging to just one loon, rather than built from the drip drip drip of deep-seated anti-Muslim sentiment that is being allowed to percolate through Europe.

Yet Breivik’s thinking shows clear evidence of influence from European and American writers and anti-Muslim movements. Breivik also connects himself to Europe’s dark chapter of Nazism by stating: “I have done the most spectacular and sophisticated attack on Europe since the Second World War.”

Breivik claims he was in touch with English Defence League members in the UK and provided them with “ideological material”. If he is telling the truth, it is further evidence of the fact that he is not a one-off, but instead is part of an alarming wave of hatred building up in the continent.

The EDL is also a concoction of these ignorant tiny conflations that fuel hatred. The EDL’s co-founder, Tommy Robinson, this week found a photograph of cricket being played outside a mosque on Twitter’s home page and tweeted: “Welcome to Twitter home page has a picture of a mosque. What a joke #creepingsharia”. His attempt at stoking hatred against Muslims was derailed by other more humorous tweets: something that gives us hope against the perfidious drip of hatred.

Mocking tweets include examples such as “I skipped breakfast this morning. Clearly fasting subconsciously. #CreepingSharia” and “If you look really carefully, a packet of iced gems looks like lots & lots of little Mosques. #creepingsharia”.

Let’s hope that whether facing tiny drops of hatred, or utter venom, that humour and common sense will prevail. Europe has already once suffered by listening to the drip feed of hatred. It’s time to stop this new tide of hatred right now.

May 7, 2012

The West appreciates Islamic art – so why don’t Muslims?

My op-ed published in The National newspaper last week.

Last week, an unprecedented exhibition about the Haj finally closed at the British Museum in London, having gathered praise around the world. The coverage focused on how this was the first known exhibition of its kind about the Haj anywhere in the world, let alone in the West; and how it moved audiences away from the political discourse about Islam and into the human experience of being Muslim.

Showcasing Islamic art has become a widespread trend in the West, a movement that can be traced to the aftermath of the events of September 11, 2001. There is a palpable desire in the West to understand Muslims better through arts and culture. After all, art is traditionally a vehicle through which the West makes sense of its place in the world, and which acts as a safe space to discuss thorny cultural and political issues. One of the curators of the exhibition captured this by expressing her aspiration that the show would allow people to stand in Muslim shoes. It seems to be working.

Showcasing Islamic art has become a widespread trend in the West, a movement that can be traced to the aftermath of the events of September 11, 2001. There is a palpable desire in the West to understand Muslims better through arts and culture. After all, art is traditionally a vehicle through which the West makes sense of its place in the world, and which acts as a safe space to discuss thorny cultural and political issues. One of the curators of the exhibition captured this by expressing her aspiration that the show would allow people to stand in Muslim shoes. It seems to be working.

In Paris, the Louvre will open its Arts of Islam gallery later this summer with a specially designed roof inspired by an Islamic veil. At a time of heightened racial and religious tensions in France, and record support for the anti-immigrant Front National, this is both an irony and a sign of hope. Perhaps through art France can suck the politics and hatred out of its relationship with its Muslim citizens.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York reopened its Islamic art galleries at the end of last year after an eight-year closure. Its curator describes how Islamic arts can illuminate the meaning that Islam brings to a vast global population. “Islam is not a single lens through which we view and interpret the art,” said Navina Najat Haidar, curator and coordinator in the Met’s department of Islamic art. “Rather, it’s an inverted lens that reveals great diversity.”

The surprise, however, is not that the West is producing and devouring art and heritage from the Muslim world, but that Muslims themselves are proving much slower at the same activities. However, they are gradually beginning to grasp that the arts are a means of dialogue and mutual understanding.

In Canberra, Australia, a Muslim group is seeking to build an Islamic art and history museum to “educate people on their magnificent contribution” and their long history with the nation, with Muslims trading from what is now Indonesia long before the arrival of the first white settlers.

It would also strengthen ties with two of Australia’s biggest trading partners, Indonesia and Malaysia. They are right that art has a way of revealing humanity and reality that can be obscured by political extremism, rhetoric and downright hatred. There is also a certain symmetry to using historic trade and cultural relationships in order to foster future trade and culture.

In a global climate where walls are being built between Islam and the West faster than they are being torn down, the arts create a much needed chink of light.

But these developments also leave me wondering about whether there is an appreciation among Muslims, for other Muslims to experience the joy of creativity and the preservation of heritage? Do Muslims see art as a means of intra-ummah dialogue and an understanding of our own selves and our contexts?

Sometimes I despair that it is too much for show, trying too hard to prove our artistic and cultural heritage rather than to enjoy and learn from it for ourselves. I want Muslims to enjoy, preserve and use arts for themselves, as well as for dialogue. We need to establish definitively that the arts are important. We need to invest in them. And we need to offer up creative space to them to develop new forms.

In fact there is a peculiar dichotomy of wanting to show off our arts and culture to others, while diminishing their value to the ummah. When others destroy Islamic heritage (in Israel, for example), Muslims are quick to point it out – and rightly so. However, when respected archaeologists raise similar concerns for heritage sites in countries such as Saudi Arabia, there is thundering silence.

Heritage must be preserved so that we can understand the context of who we are. In my opinion, for Muslims this is a divine command, as the Quran talks clearly about travelling the world to see what has passed before.

The Gulf slowly but surely is realising the value of recognising the importance of its cultural roots. There has been a mushrooming of museums and galleries being commissioned and opened over recent years, attempting to tell the story of the region’s heritage. The British Museum and the Louvre are in the forefront of the creation of Saadiyat island’s cultural district.

The question is, who is this all for, and what is the purpose? The museums, artistic endeavours and exhibitions should be there to help us work through the issues of the present, by offering new lenses on current predicaments. They must allow us to delve into our past – both the good and the gory – to make sense of the current challenges in the Muslim world, to allow us to converse across countries, ethnicities, languages and cultures and make sense of why we are where we are.

In short, we need the arts to understand how we got here today and why we are facing the challenges we face. We need the arts to offer us up creative vistas on how we move forward from today’s challenges.

We are still at the early stages – still only able to put forward a rose-tinted view of Muslim heritage that serves the much-needed purpose of building our confidence, and introducing us to our own past. But in getting to know the past we must get to know not just the positives but the ups and downs, the contentions, the challenges and all those stories we might want to forget, that don’t fit with the glorious narrative we wish to display.

Part of the problem is that we don’t know how to understand, how to embrace and promote arts. We must open ourselves up to new influences in theatre, poetry, music, language, rhythm, architecture even as we remain true to our Islamic artistic heritage. We must incorporate them willingly instead of rejecting new forms as “un-Islamic”, or only reluctantly accept them as part of Islamic expression. Where do we think the art forms we now promote so passionately come from in the first place?

New music development, for example, is in its early stages but is usually frowned upon. Yet people love Qawwali, which itself must have been a struggling new medium once before blossoming into the art form it is today. Theatre is the same: a new shape to the storytelling heritage of the Muslim world. We need to give time and investment for art forms to develop.

The arts have their place in civilisational dialogue, for sure. But to limit that dialogue to politics is to short-change the arts and ourselves. Worse is to use the arts as a public relations tool while disregarding their ability to help us understand ourselves, our faith and our history. Used wisely, the arts also have the creative power to help us shape our future.

Shelina Zahra Janmohamed is the author of Love in a Headscarf and writes a blog at www.spirit21.co.uk

Dear men, time to support us women…

My weekly column ‘Her Say’ for The National newspaper, published on Saturday…

More than a year on from the start of the Arab uprisings, it’s time to ask: are things getting better for the Arab world? More specifically: are things getting better for Arab women?

War, social upheaval and often a low starting point for women’s rights have made us hopeful of radical transformation. But this fundamental question – are things getting better for women? – can be applied to any country, any ethnicity and any religion. In fact it must be applied to all, because women everywhere need things to get better.

War, social upheaval and often a low starting point for women’s rights have made us hopeful of radical transformation. But this fundamental question – are things getting better for women? – can be applied to any country, any ethnicity and any religion. In fact it must be applied to all, because women everywhere need things to get better.

In India millions of pregnancies are terminated simply because the foetus is female. In China women are kidnapped as brides because the one-child policy has led to a surplus of men. In France one in 10 women is a victim of domestic violence. Two women are killed each week in the UK by current or former male partners. In the US women earn approximately 77 cents for every dollar that men earn.

Across cultural, religious and geographic divides, women are discriminated against in similar ways, just with different manifestations. We are all in this together, and should all be fighting on the same side. But how one defines “we” must change. It is important that men step into this debate, too. Not at a political or academic level, but at the human, emotional and enraged-by-the-lack-of-justice level.

I understand that this is an issue first for women, and that men might not want to be seen as telling women how they feel and what they want. But the fact is, men rarely ask why women feel this way, and how men can help change things. Why is it that when public cries are raised about women’s issues such as oppression, discrimination, physical and psychological abuse, and downright secondrate treatment, male voices are so rare in the conversation? Men have an innate sense of fairness, love and justice. So why do they show it so rarely on this topic? Why is there such reluctance to hold other males accountable for their silence?

Perhaps the trouble is that some men see women’s rights as a problem of individuals, nasty single men who perpetuate these crimes. That doesn’t make the collective silence right.

We need to ask these questions because the answers can help us create strategies that lead to real change. Real change is the ultimate goal for all women, no matter where they are.

April 15, 2012

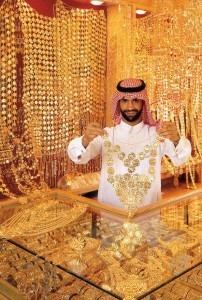

The burden of gold jewellery must be removed from weddings

This is my weekly column published in The National yesterday.

The wedding season is upon us. Young people might be thinking about love, but for families this can be a time of great anxiety as weddings mean hefty bills. And this year they have one additional worry: the eye-wateringly high price of gold.

From a young age, my family and wider community would talk with concern about building up wedding trousseaus for their daughters, made up of fancy frocks and gold jewellery. During wedding festivities, jewellery and clothes would be put on display for in-laws to inspect. The purpose was never clear to me, although I assumed it was to show-off how endowed the bride was, and more importantly to stop snide remarks from the in-laws about stingy or poor parents. It all felt shallow and exhibitionist to me.

From a young age, my family and wider community would talk with concern about building up wedding trousseaus for their daughters, made up of fancy frocks and gold jewellery. During wedding festivities, jewellery and clothes would be put on display for in-laws to inspect. The purpose was never clear to me, although I assumed it was to show-off how endowed the bride was, and more importantly to stop snide remarks from the in-laws about stingy or poor parents. It all felt shallow and exhibitionist to me.

Nonetheless, once I started work and before I got married I started to purchase gold jewellery for myself as I’m fond of the sparkly stuff. The fact that it would add to my collection when I got married – oh happy day! (but first I had to find a groom) – was a lovely bonus. Although the gold jewellery was an indulgence, compared to today’s prices I was fortunate that the price of gold at that time was comparatively reasonable.

By the time my wedding date was set, I had a respectable amount of gold jewellery for my wedding so that my family did not need to take out a mortgage to purchase more. I bought it because I liked it, not because I had to. Besides, what an anachronism to give gold, when the groom is already getting the girl: is she not valuable enough, yet we have to bribe him with gold on top?

If there is pressure on the bride’s family to stump up gold, the groom feels the burden too, often preventing or delaying marriage. He can’t turn up to the wedding empty-handed. After all, what kind of self-respecting father of the bride could accept a son-in-law with no pointless trinkets to sit in the bank even if he has to take out a loan to get them, or can’t afford a house and other basic necessities (but at least he has a shiny necklace to give)?

In India, 10 million annual weddings clock up consumption of half the world’s gold. The average middle class family spends more than Dh18,000 on wedding jewellery. Worried you won’t have enough gold to marry off your daughter? Savings accounts are on offer for families to build a gold fund from birth. After the wedding, the gold probably goes back in the bank.

What a shame, the money could be put to far better use: the deposit on a house, a car, education, or simply savings for a rainy day. But no, it’s all about status, a deeply crass form of putting wealth on display. And it drives families into paralysing and totally unnecessary debt, or delays couples getting married.

The problem is that the gold-giving custom is so entrenched in so many cultures it’s going to take some radical couples to dispense with it. However, I think the time has come to get rid of the mandatory and all-encompassing nature of this tradition. I’m all for pretty jewellery, but we should temper expectations and pressure. Perhaps it’s time to introduce the idea of passing just one small item of jewellery down from mother to daughter as a sign of prestige, and make piles of shiny new bling the second rate choice.

While you’ve been reading this, the price of gold has gone up again. Bet you wished you’d started that gold fund.

April 7, 2012

Easter should be for Christian remembrance, not for chocolate

Here's my weekly newspaper column published today in The National

The shelves at my local supermarket are straining beneath the weight of chocolate eggs and hot cross buns, in anticipation of Easter this weekend. While these luxuries are being wolfed down by many, Christians are marking their belief in the event of Jesus's crucifixion, burial and subsequent resurrection.

As I enter the store I'm hit by the notion that this weekend is not Easter, but a Festival of Sugar. As a lover of chocolate in particular, I'd be right behind the creation of Chocoholic Sunday (marketers take note: you heard it here first). But why oh why does a very serious religious celebration about betrayal, sacrifice and redemption need to be turned into a cutesy commercial extravaganza?

As I enter the store I'm hit by the notion that this weekend is not Easter, but a Festival of Sugar. As a lover of chocolate in particular, I'd be right behind the creation of Chocoholic Sunday (marketers take note: you heard it here first). But why oh why does a very serious religious celebration about betrayal, sacrifice and redemption need to be turned into a cutesy commercial extravaganza?

While Easter is pivotal to Christian doctrine, as a Muslim, I don't accept the premise of crucifixion and resurrection. For me, Jesus was not God, nor the Son of God, nor part of a Trinity. He was a human being, albeit a prophet, whom I hold in extremely high status. However, like significant events in all religions, I believe it is important to respect the believers of that religion and their reverence for the event. Just as I feel dismayed at the increasing commercialisation of Ramadan and Eid, I feel the same dismay at the commercialisation of Easter.

Easter doesn't suffer as badly as Christmas, which has turned into an extenuated and indulgent shopping fest. That's probably because the gory events of Easter are much less easy to paint with a romantic cuddly brush. But at least most people have an inkling of the core message of Christmas: the birth of Jesus, hope, peace and goodwill. Easter's more complex messages are waylaid at the hollow altar of crème eggs and cuddly bunnies.

Survey after survey show that the meaning of Easter is slowly being lost. In the United States, Barna Group noted that only 42 per cent of adults could identify that Easter was about resurrection. Yet the National Retail Federation says Easter spending could top $16bn (Dh59bn) this year, the average household spending $145.

The story is the same in the UK, where Reader's Digest found only 48 per cent of people could identify the story of Easter. Shopping has become such an ingrained part of the occasion, that a supermarket managed to mess up, not once but twice. The Somerfield chain had to reissue a press release about the meaning of Easter, claiming first it was about the birth of Christ, and then about his "rebirth".

So why, as a Muslim, do I care? Shouldn't I be pleased that a religious occasion at odds with my own theology is disappearing? Far from it. It's important to respect other faiths, and even more so to share the universal morals from their stories. Easter follows the occasion of Lent, a period of self-restraint, reminiscent of Ramadan. Then there is the lesson of betrayal: those who sell themselves out like Judas will live and die with regret. And a vital point: there are those who believe in the ideals of justice and equality with such passion that they are willing to sacrifice their own lives.

Bunnies are cute, and chocolate eggs are tasty. And it's true that there's a gap in the calendar for a Chocoholic Sunday. It doesn't need to be on Easter Sunday.

While we might not accept the premise of the occasions of other religions, we should mourn the fact that festivals such as Easter and Ramadan – which have much to tell us about ourselves and the human predicament – are being turned into shopping and eating extravaganzas.

April 6, 2012

Pasties, power and forgotten promises to the the people

A little belatedly, here is my column from last week's National

Leaders around the world, beware! If you've forgotten how important it is to be in touch with those you lead, then take an object lesson this week from the British chancellor, George Osborne. In his latest budget pronouncement, he introduced a tax on hot pasties – those deep-filled pastries so beloved of ordinary Brits during their lunchtimes.

Leaders around the world, beware! If you've forgotten how important it is to be in touch with those you lead, then take an object lesson this week from the British chancellor, George Osborne. In his latest budget pronouncement, he introduced a tax on hot pasties – those deep-filled pastries so beloved of ordinary Brits during their lunchtimes.

Osborne was asked with barely-hidden derision about the last time he bought a pasty from Greggs, the country's largest high street bakery. He looked stumped and this has had the media running headlines underscoring the fact that his party is out of touch with ordinary people.

In fact, in just the last two weeks, his Conservative Party appears to be less and less in touch with "normal" people. Its co-treasurer was secretly filmed offering access to dinner with the prime minister, David Cameron, along with the possibility to influence policy for £250,000 (Dh1.46 million); they've cut tax for the richest earners; and refused to raise allowances for pensioners, creating more headlines about "granny taxes". They couldn't have paid for better re-enforcement of their brand as the party of the rich if they'd tried.

The accusation of being out of touch with people is damning for any form of government, but it is the worst form of insult in a democracy where power is supposed to reside with the people. As the Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu put it, leaders are worst "when people are contemptuous".

But leaders, beware! Danger also lies the other way. The French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, is pandering to the extreme right to win voters back from the Front National, by playing up to the lowest common denominator of anti-immigrant racist sentiment. In a country that already faces huge social problems, and in whose living memory remain the horrors of Nazi atrocities and the Second World War, his actions in fomenting such attitudes to win votes are despicable.

While democracy empowers people, surely one of its unavoidable curses is that leaders must divert their energies, attentions and resources while wooing the electorate. Watch any US presidential hopeful and you'll see the vast financial outlay, the hordes of volunteers, the months (if not years) dedicated towards voter seduction. The 2008 elections are said to have cost $1.8 billion (Dh6.6bn), double the amount of 2004. This year's race will probably cost even more. Is this really power to the people, or is the truth that money talks, and big money brings big power?

Even social activists and religious leaders understand that they must win the hearts of the public if they hope to effect the change that they believe society needs.

Ultimately, inspiring and effective leaders are those who combine the visionary with the common touch. They understand the here-and-now of our lives but can galvanise us towards something different, something better.

What we hope from politicians is that they show moral leadership and move countries forward while remaining in touch with the reality of life as most of us live it. We expect some backbone and some respect. We are not aliens who should eat colder food, have base attitudes fanned, nor have our allegiances bought. Leaders, beware: we are the people, and in your actions you are accountable to us.

Shelina Zahra Janmohamed's Blog

- Shelina Zahra Janmohamed's profile

- 175 followers