Megan Abbott's Blog, page 2

June 20, 2011

a bell in every tooth

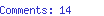

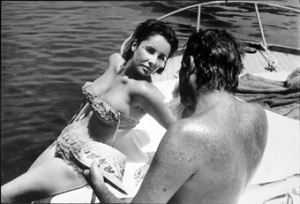

"I don't want to be that much in love ever again." —Elizabeth Taylor

I'm reading Furious Love (not to be confused with Furious Love), which recounts the tumultuous romance of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Prior to reading it, I had no burning interest in the pair but was drawn to it because it's co-written by Sam Kashner, author of the vivid, gossipy Bad and the Beautiful: Hollywood in the Fifties, one of my favorite tinseltown books.

As I began, I suppose I expected the Liz-and-Dick relationship to be some kind of amalgam of Frank and Ava and Albee's George and Martha. Both analogies have significant weight, but the depth of their connection to each other is woundingly touching, and the giddy, intense bond they had is kind of a heartbreaker as you see the increasing damage done by mind-numbing drink and other excess, career disappointments, Burton's depression, family sorrows.

I have always loved Richard Burton and he shimmers in these pages. I think one of my favorite cinematic moments is a fleeting moment from Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf. After a night of epic drinking the beleaguered George, watching his wife tantalize another man on the dance floor with some ribald hip shakes, announces wearily—but with distinct admiration, "You have ugly talents, Martha."

One of the gifts of Furious Love is the rich sense of Burton's Welsh upbringing, which, to me, feels terrifically exotic and dramatic, with rich descriptions of the life of miners (Burton was the son and brother of miners), Burton's love of "lava bread," a Welsh concoction of a "froth of boiled seaweed "plunked down on the plate like a cow pat," the way his brother's face was "pocked with little blue marks," from his years in the mines.

But my favorite part of the book might be the words offered up by Richard Burton himself, both from his various writings, diary entries and from his love letters to Taylor, which she permitted use of for the first time. Many are hopelessly romantic. Some are deliciously dirty, with Burton telling Taylor how he longs for her "divine little money-box," the "exquisite softness of the inside of [her] thighs," and for the "half-hostile" look in her eyes when the pair is "deep in rut." That "half-hostile," to me, is the mark of writerly (and perceptual) brilliance.

While Kashner and his coauthor Nancy Schoenberger are careful not to push the point, there's a piece of Burton's stormy past that seems to whisper in our ear constantly as we understand his connection to Taylor. His mother dead when he was only two, Burton was raised mostly by his sister, Cis, whom he viewed in saintly proportions and about whom he wrote lovingly:

I shone in the reflection of her green-eyed, black- haired, gypsy beauty. She sang at her work in a voice so pure that the local men said she had a bell in every tooth… She was naïve to the point of saintliness and wept a lot at the misery of others. She felt all tragedies except her own. I had read of the Knights of Chivalry and I knew that I had a bounden duty to protect her above all creatures. It wasn't until 30 years later, when I saw her in another woman that I realized I had been searching for her all my life.

We're always, in our relationships, looking to repeat, recapture past ones, aren't we? And it isn't always (or even mostly) a bad thing. Burton and Taylor saved each other for a while, until they couldn't any longer. As Taylor wrote to Kashner, when releasing Burton's letters to the biographer, "We had more time but not enough."

June 19, 2011

Murder, In Song

As much as I crave a good book about murder or a crime scene photo to dissect, nothing compares to a musical ballad about murder and mayhem. One of my old favorites is a rendition of “Knoxville Girl” by the Louvin Brothers off the Tragic Songs of Life album (1956). These country brothers crooned about the violent riverside murder of an unnamed young woman by her suitor. Voices sweet and lamenting, the Louvin brothers obscured the shock of violence with their lullaby composition.

“I met a little girl in Knoxville, a town we all know well,

And every Sunday evening, out in her home I’d dwell,

We went to take an evening walk about a mile from town,

I picked a stick up off the ground and knocked that fair girl down.”

You can only imagine where it goes from there. Listen here.

The Louvin Brothers can’t be credited with inventing the murder ballad. In fact, “Knoxville Girl” is based on an old Irish ballad, “The Wexford Girl”, which has a more elaborate warning against murdering your loved one. Murder Ballads can be traced back even further to England and to the broadsheet ballad “The Cruel Miller” and well, it’s anyone’s game from there.

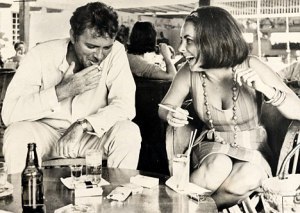

Now, take the traditional murder ballad and mix it with the poetry of a notorious serial killer, with a nod toward Joyce Carol Oates, and you have Jon Derosa’s “Ladies in Love.” Based on a poem of the same name by Charles Schmid, Jr., DeRosa weaves some lines from Schmid’s prison writing into his evocative ballad and gives us a precise window into the macabre mind of The Pied Piper of Tuscon. For those of you who don’t know, Schmid was an odd character who wreaked havoc on the city of Tucson in the 1960’s and served as the inspiration for Joyce Carol Oates’ short story, Where are You Going and Where Have You Been?

Photo courtesy of the Tucson Citizen.

He blurred his natural attractive features with cartoonish makeup and clothing, turning himself into a minstrel Elvis Presley – dark tan pancake makeup, white lipstick and the King’s jet black mane. He added his own touches too: a beauty mark on his cheek made from a mixture of putty and axle grease and oversized cowboy boots stuffed with detritus to make him seem taller, attempts at being a more appealing lady magnet to the disaffected youth of Tuscon.

Here, DeRosa has crafted a hauntingly beautiful murder ballad with flutes and woodwinds by Jon Natchez (of Beirut/Yellow Ostrich) and gentle violins and cellos by Claudia Chopek and Julia Kent, respectively. Schmid’s chilling proclamation that “ladies should never fall in love,” is sung sweetly, like a lullaby by DeRosa. And Schmid’s poetic line about women’s voices “being like small animals waiting to be fed” is seemingly easier to take here, layered and somber. But, his complicated and perverse relationship with his victims isn’t celebrated here; instead, DeRosa’s tale of woe serves as a time capsule of terror that I believe, deserves a place in the history of disquieting murder ballads.

Listen to “Ladies in Love” exclusively on The Abbott Gran Medicine show:

http://soundcloud.com/jonderosa/jon-derosa-ladies-in-love

Jon DeRosa’s Anchored EP can be picked up on Itunes or here.

June 8, 2011

prepare to be amazed!

Recently, I came upon a YouTube clip that felt like uncovering a childhood book at the bottom of an old box. One you don't remember at all until you see its cracked cover and then every illustration, every odd turn-of-phrase, comes rushing back.

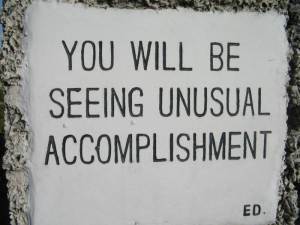

In this case, it was documentary segment dedicated to a miraculous structure called the Coral Castle. Located about 30 miles south of Miami in Homestead, Florida, it is one of those odd buildings—Mystery Castle in Phoenix and Winchester Mystery House in San José are others—that are the result of one "ordinary" person's eccentric quest to create something extraordinary.

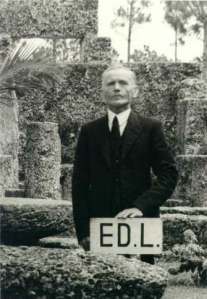

Coral Castle is the improbable—impossible?—product of one man: Edward Leedskalnin, a 5-ft. tall, 100-lb. Latvian immigrant who cut, quarried, transported (ten miles), and raised the entire structure, which consists of more than 1,100 tons of coral rock, alone.

While, in that part of Florida, coral can be 4,000 feet thick, Leedskalnin reportedly used only hand-made tools, with no large machinery and no workers assisting him. Among much of the disbelieving press about the Castle—particularly during its early years—much nasty head-shaking was made not just over the fact that one man could build something like this, but that an "illiterate immigrant" could. According to the Castle's official website:

While, in that part of Florida, coral can be 4,000 feet thick, Leedskalnin reportedly used only hand-made tools, with no large machinery and no workers assisting him. Among much of the disbelieving press about the Castle—particularly during its early years—much nasty head-shaking was made not just over the fact that one man could build something like this, but that an "illiterate immigrant" could. According to the Castle's official website:

When questioned about how he moved the blocks of coral, Ed would only reply that he understood the laws of weight and leverage well. This man with only a fourth grade education even built an AC current generator, the remains of which are on display today. Because there are no records from witnesses his methods continue to baffle engineers and scientists, and Ed's secrets of construction have often been compared toStonehengeand the great pyramids.

At a certain point during its long construction point, Leedskalnin opened his monument to the public, offering tours for 10 cents. Apparently, he even served up hot dogs for visiting children, the product of a pressure cooker he had invented.

The work of the Castle absorbed him from 1920 until his death in 1951.

The best part of the story, though (for me), is not the triumph of one dedicated (obsessive) man to overcome expectation, engineering, and our conceptions of what's possible (though that's pretty good too). It's the reason why Mr. Leedskalnin built the castle to begin with. I bet you know why.

The best part of the story, though (for me), is not the triumph of one dedicated (obsessive) man to overcome expectation, engineering, and our conceptions of what's possible (though that's pretty good too). It's the reason why Mr. Leedskalnin built the castle to begin with. I bet you know why.

Like an "everyman" Charles Foster Kane building his Xanadu for his beloved. In this case a woman Leedskalnin referred to as his "Sweet Sixteen," a young woman with the Dickensian name of Agnes Scuffs. At age 26, Leedskalnin was engaged to Miss Scuffs, ten years his junior, but, legend has it, she broke off the relationship on the eve of their wedding.

A fascinating (and to my mind, quintessentially American) figure, Leedskalnin was not just a sculptor, he was an inventor, a theorist on the properties of magnetism and a writer, the author of five "pamphlets." Three are dedicated to "Magnetic Current" and one to "Mineral, Vegetable and Animal Life" The fifth is called A Book in Every Home: Containing Three Subjects: Ed's Sweet Sixteen, Domestic and Political Views. In it, Leedskalnin writes about "Sweet Sixteen" as more than a single Agnes Scruffs but a symbol for the kind:

Now, I am going to tell you what I mean when I say, "Ed's Sweet Sixteen." I don't mean a sixteen year old girl; I mean a brand new one.

Later, he writes:

…I want a girl the way Mother Nature puts her out. This means before anybody has had any chance to be around her and before she begins to misrepresent herself. I want to pick out the girl while she if guided by the instinct alone

And he expand to larger social views:

Everything we do should be for some good purpose but as everybody knows there is nothing good that can come to a girl from a fresh boy. When a girl is sixteen or seventeen years old, she is as good as she ever will be, but when a boy is sixteen years old, he is then fresher than in all his stages of development. He is then not big enough to work but he is too big to be kept in a nursery and then to allow such a fresh thing to soil a girl—it could not work on my girl. Now I will tell you about soiling. Anything that is done, if it is done with the right party it is all right, but when it is done with the wrong party, it is soiling, and concerning those fresh boys with the girls, it is wrong every time.

Indeed, Mr. Leedskalnin. Indeed.

(I do not remember any of these details of the story from when I first became fascinated by the castle—which I've yet to see!—at age eight or so. I'm sure, however, that, at that age, I would have taken due note.)

Mr. Leedskalnin never married. While he extended invitations to Agnes Scuffs over the years, she never did see the monument he built for her.

Mr. Leedskalnin never married. While he extended invitations to Agnes Scuffs over the years, she never did see the monument he built for her.

Postscript: I am sure there are folks out there who know much more than I do about Coral Castle (Dennis, help me!), or who have visited it. If so, tell me more!

June 6, 2011

hurry up please it’s time

Sunday’s New York Times ran an interesting piece that speculated about why Hollywood seems to have so few (and even fewer successful) movies with preadolescent girls (roughly ages nine to 14) at the center. While the book market for this age group is booming, the carryover to film has been far less reliable. While movies like 13 certainly depict the perils (in a way that reminded me mostly of the best art-directed after-school special ever) of the age, this article focuses instead on movies targeting preadolescent girl viewers.

Sunday’s New York Times ran an interesting piece that speculated about why Hollywood seems to have so few (and even fewer successful) movies with preadolescent girls (roughly ages nine to 14) at the center. While the book market for this age group is booming, the carryover to film has been far less reliable. While movies like 13 certainly depict the perils (in a way that reminded me mostly of the best art-directed after-school special ever) of the age, this article focuses instead on movies targeting preadolescent girl viewers.

The author, Pamela Paul, speculates as one of the reasons these movies struggle is that ”The tween occupies a shifting space between the girl who has carefree adventures and the sexy teenager who angsts. It’s a phase that makes both parents and Hollywood executives uncomfortable.”

I’m sure this is true. My new book, The End of Everything, is from the point of view of a 13-year-old girl and I guess I picked that age because there is hardly a time of more “cuspiness.” It’s a time when the world still seems (at least, in my generation) mysterious. Even when your days are mostly filled with the tedium of school and killing time and searching desperately for moments of unsupervised anything, you are old enough to peer into a world infinitely more exotic, substantial and intoxicating than your own. To get a taste of it. It’s such an eye to the key-hole age. But, of course, you usually don’t know what to do once those doors creak—or fling—open.

One of the films mentioned in the piece as a rare positive example is The Man in the Moon (1991), which I remember getting it pretty right. The main character, Dani (Reese Witherspoon), is 14 and develops a crush on her 17-year-old neighbor. The two begin a flirtation but once the neighbor meets Dani’s more age appropriate sister, everything feels taken from her. There are some dark plot turns, but they are not sordid ones. And they feel very real.

One of the films mentioned in the piece as a rare positive example is The Man in the Moon (1991), which I remember getting it pretty right. The main character, Dani (Reese Witherspoon), is 14 and develops a crush on her 17-year-old neighbor. The two begin a flirtation but once the neighbor meets Dani’s more age appropriate sister, everything feels taken from her. There are some dark plot turns, but they are not sordid ones. And they feel very real.

The Man in the Moon is set in the 50s, and, thinking too of 14-year-old Matty Ross in True Grit, I wonder if period films manage this better, or we manage them better. They feel less close to us. Less close to home. And the social mores, more conservative, seem to assure us we won’t be confronted with what we face today. Because we always feel everything is more dangerous now, and young girls—we still invest so much in their purity, their goodness.

When I was nine the “teen sex comedy” Little Darlings came out. I still remember the tagline distinctly: “Don’t Let the Title Fool You.” The stars were Kristy McNichol and Tatum O’Neal, who my favorite child actress as a kid (Bad News Bears, now that’s a preadolescent girl character you can write home about).

When I was nine the “teen sex comedy” Little Darlings came out. I still remember the tagline distinctly: “Don’t Let the Title Fool You.” The stars were Kristy McNichol and Tatum O’Neal, who my favorite child actress as a kid (Bad News Bears, now that’s a preadolescent girl character you can write home about).

With its summer camp-virginity-loss-bet, I was too young to see it, but I remember being so tantalized and so terrified of it at the same time. I think I was fairly fascinated by it and when I eventually did see it, years later, I was surprised. For all its trying-too-hard raunch, at heart it’s a movie eager to, intermittently, show something real—about the thorny relationships girls can have with each other (including as complicated by class issues) and most of all about the ways curiosity and competition can push you into some pretty hard corners. Kristy McNichol in particular gives her part so much subtlety, digging into the rawest parts of the story. And the outcome of the “bet” felt utterly, painfully real.

The girls in the movie are 15, and I think most girls like movies/books where the female leads are a couple of years older. And had I seen it as young girl, I think it would have been a complicated gift, but a gift nonetheless.