Dibyajyoti Sarma's Blog, page 27

April 8, 2016

A History of Bodo Literature

Published on April 08, 2016 05:00

Chinese Poetry

Published on April 08, 2016 04:54

Gulzar: A Pocket Full of Poems

Published on April 08, 2016 04:51

April 5, 2016

The Last Witch Hunter

It’s an adequate film in the rather unimaginative genre where a righteous Christian warrior must hunt down an evil witch to save humanity, or parts of it. Nicolas Cage and Ron Pearlman did one such film some years back. Then Jeff Bridges did one called ‘Seventh Son’.

It’s an adequate film in the rather unimaginative genre where a righteous Christian warrior must hunt down an evil witch to save humanity, or parts of it. Nicolas Cage and Ron Pearlman did one such film some years back. Then Jeff Bridges did one called ‘Seventh Son’. Here, Vin Diesel plays an undead soldier since the time of the Vikings, I guess, who must settle one final score with the Witch Queen he helped burn a long time ago, where else, in modern day New York. You know how it ends. There are fights and nice visuals. The new-age computer graphics technology has made all this rather too easy.

The movie looks good, but it terms of narrative, there is not much. The script tries, but it cannot do much as it sticks to the genre demands. There are some nice touches, like the generation of Dolans serving the undead hero, like the witches we roam among humans, like the blind magician with the butterflies, in the shape of an underutilised Isaach De Bankole. It’s really a crime to hire Bankole in a movie and not give him anything substantial to do. If you don’t believe me, ask Claire Denis?

Diesel is adequate. After all those Fast and Furious movies, you don’t really mind him anymore. After Nolan’s Dark Knight movies, Michael Caine now play a variation of the butler role in his sleep. He has tremendous screen empathy and it works well here. What do you say about Elijah Wood? After The Lord of the Rings, he seems to have lost his way? And, why they always cast him in bumbling villainous roles?

In the end, you wonder, with so much cash at their disposal, why could not they find a more exciting story to tell. But you are grateful that at least this one is not as terrible as Seventh Son.

Published on April 05, 2016 12:33

March 23, 2016

An eclectic spread @ Penguin India Spring Fever

For booklovers in Delhi, spring comes with Penguin India’s annual Spring Fever, featuring discussion and authors from the publishing behemoth’s new roaster of releases. The year, the open-for- all event took place at India Habitat Centre from 15 to 20 March 2016. There was something for everyone, from serious discussion on history from the likes of Ramachandra Guha and Sunil Khilani, to former-President APJ Abdul Kalam’s teachings to Bollywood actors discussing a range of topics, from acting to feminism to cancer to health, to the mesmerising poetry of the incomparable Gulzar.

The most interesting part of the event was the open-air library, where visitors could browse through the books from among 5,000 titles published by Penguin and Random House.

The challenge of contemporary history

Historian and writer Ramachandra Guha opened the festival with an exclusive preview of his forthcoming book, a collection of essays called Democrats and Dissenters. The book critically assesses the work of economist Amartya Sen and Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, and explores major political and cultural debates across India and the world.

Guha talked about the paradox that while India is the “most interesting country in the world,” we know so little about its contemporary history. He said there have been three great democratic revolutions – the French, the American and the Indian revolutions. While the Indian revolution maybe the most important, it is the least written about. This might be because it is the most recent and that it occurred in a continent which is not known for being a “beacon of liberty and freedom.”

“Indian history is a thriving, rich productive field, but much of it, in my view, too much of it focuses on the colonial period. That is from 1757 to Partition in 1947,” he said, adding that there has been an almost unhealthy obsession with colonialism. This means that our historians have neglected the period before and after colonialism.

Guha then proceeded to talk about the four major challenges that a contemporary history writer faces.

First, the reader of a contemporary history writer’s book was not a “passive recipient of the text.” The reader will have strong prejudices and opinions about the recent past, especially about political leaders. “The reader is a critical citizen. His or her ideological and social preferences, even before you offer your history, they know all about it. You may write a 500-page book based on careful research, but they’ll approach that book already knowing what this book about Nehru or Ambedkar is all about,” he said.

Second, the contemporary historian, like the reader, is also not free from prejudice and opinions.

Third is the density of sources. He claimed that because the British kept most of their files, there is so much material for colonial historians to use. “Our governments either don’t keep files or they shred them when they leave office. Even if they keep them, they do not transfer them to the national archives,” he added. Guha said historians need primary sources to work with. Unlike the colonial sources, the recent past sources were “scanty and imperfectly kept and sometimes not available at all.” Unlike most democratic countries, where the papers of leaders are properly archived and open to scholars, in India, the families of the leaders get the papers, which they do not share.

The fourth one, Guha said, is a “peculiarly Indian challenge.” It is to do with the disciplinary boundary in the Indian universities. “When the clock struck midnight on 14 August 1947, history ended and political science began.”

Talking about his book, Makers of Modern India, Guha said India is undergoing five revolutions simultaneously. A political revolution, where a society based on feudal elite moved to system where every citizen has a vote. A national revolution, where a nation ruled by foreigners we now have swaraj. An industrial revolution where an economy based largely on agriculture is becoming industrial. An urban revolution where settlement patterns based on villages are becoming city based. And, a social revolution where tradition hierarchy, particularly, on caste and gender are being challenged. Unlike other countries where these revolutions have staggered, India is undergoing these revolutions now. “We are extremely large and extremely diverse and we are undergoing these revolutions. That’s why as a historian, I am privileged to be born in India. I could spend five lifetimes writing about these five revolutions,” he said.

The author also took the time to talk about extremism. He said extremists talk the loudest and that they see the world in black and white. He added that this certitude prevented us from “understanding the complexity of our country.” Hindu extremism, he believes, is not new and that Hindus are “a majority with a minority complex.” While globally, Islamic terror was dangerous, Guha feels that Hindu fundamentalism is dangerous in India.

Incarnations: India in 50 Lives

On Day Two, author, historian, and professor Sunil Khilnani came out to present and discuss his most recent work, Incarnations – an account of 50 lives that have influenced the Indian civilization.

Khilnani started his talk with an anecdote. “Some four decades ago, a violent storm hit Sannati – a small village on the Bhima River in northern Karnataka. The roof of the village temple collapsed, and the image of the deity – Kalikambal – was crushed. The image had long stood on a large stone slab. As the workers cleared away the stone’s debris, the slab flipped over, and on the underside were inscriptions in the Brahmi script – fragments, archaeologists would later determine, of two rock edicts of the third century BC emperor, Ashoka. The subject of one of the buried edicts was, as it happens, the importance of respect for the beliefs of others. “As I reflected upon that edict in Sannati, I was struck by the historical irony: Ashoka’s optimistic words on religious tolerance had been literally turned upside down – cut up and repurposed as a platform for a Hindu goddess,” he said.

Khilnani recorded: “India’s past is an arena of ferocious contest, its dead heroes springing back to life and dispatched to the front-lines of equally ferocious contemporary cultural and political battles.”

It is in that context that Khilnani wants to “restore the individuals to their rightful places” because, as he poignantly begins his book by saying, “Indian history is a curiously unpeopled place. As usually told, it has dynasties, epochs, religions and castes – but not many individuals.”

Khilnani then proceeded, with a host of images, to offer the range of his book: It explores 50 lives across 2,500 years of Indian history – from the “moral preoccupations” of the Buddha to the “capitalistic” energy of Dhirubai Ambani, via famous, and not-so-famous, monarchs, artists, writers, thinkers, leaders, and freedom fighters.

“One of my criteria for inclusion [of these characters],” Khilnani said, “was the light old lives might shed on urgent issues of the present.” Championing the fact that India has always been a “messily hybrid, multi-ethnic, multi-religious place, where identity, the social order and religious convictions have always been in flux and open to challenge”, the author eloquently reminded the audience: “What has driven India forward is the role of individual dissent!”

Khilnani said that he had a “big list” of individuals to begin with and he had to select and omit – some unpopular selections being the lives of the forgotten Malik Ambar and Chidambaram Pillai, and a striking omission being that of Pandit Nehru. Dr. Khilnani explained in the introduction: “I have chosen to leave out some familiar names, to allow space to bring in a few others who should be more widely known – a choice with which I think one of the figures I have excluded, Nehru, would have agreed”.

Pakistan is in the eye of the beholder

Day Three saw five highly opinionated achievers taking to the stage. The panelists were: Shashi Tharoor, author and politician; TCA Raghavan, author and former High Commissioner to Pakistan; Taslima Nasreen, author and activist; Hindol Sengupta, author and journalist; and Neeraj Kumar, author and former Commissioner of Delhi Police. Joining them through a video recording was Husain Haqqani, author and Pakistani diplomat.

“Every country is only in the eye of the beholder!” Husain Haqqani said, underscoring the point that each country rises and falls in other people’s eyes according to the experiences they have had with the country. “What we [in Pakistan] have to figure out is how Pakistan can live at peace with itself and with its neighbors,” Haqqani added.

When Shashi Tharoor starts to speak, one hardly remembers that he is a former diplomat or, for that matter, a member of a particular political party. He outgrows limitations to speak his mind, and he speaks well. “I tend to behold Pakistan with a heart of a dove and with a head of a hawk!” Shashi Tharoor began. “Kashmir is not the core problem... the real problem between India and Pakistan is the nature of the Pakistani state. In India, the state has the army; in Pakistan, the army has the state,” he said.

TCA Raghavan pointed out that Pakistan is a country with 200 million people who possess a “very strong sense of themselves”, and, therefore, we shouldn’t underestimate them, or just rely on state policies. “Whatever change might come about is largely not going to be because of external factors, or because of India. It’s going to be come about from what they do with themselves and how they imagine their future,” Raghavan reminded the audience.

Taslima Nasreen writes powerfully but speaks softly, and takes her time to pace herself. When asked to present her thoughts on Pakistan, the Bangladeshi author, who now lives in the US, shared with the audience the poignant anecdote when, during the 1971 war, Pakistani army raided her home, amongst many other homes in Bangladesh. “They tied my father to a coconut tree and they tortured him... I heard the sound of heavy boots in the room I was sleeping in... they looted our house... and burnt villages.”

As a hardcore critic of blind faith, Taslima Nasreen didn’t pull her punches yet again: “If you create a country on the basis of religion, that country becomes a fundamentalist country”.

As the former Commissioner of Police and investigator of numerous terror attacks in India, Neeraj Kumar, immediately outlined the laxity on the part of India: “In each one of the them [the terror attacks] it was conclusively proven that the establishment [in Pakistan] had a role... We are always reacting [to what Pakistan does].”

Much like an investigator, Neeraj Kumar underscored the pattern of the terror attacks, and, thus, the motives: “They have the clear target to attack the great icons of the country to show that nothing is safe... and they adopt the most insidious strategy.”

Much like Husain Haqqani, Hindol Sengupta began by drawing a clear line between the state of Pakistan and the people of Pakistan: “Friendship between the individuals in India and Pakistan is different from the state called Pakistan. You have to distinguish.”

Commenting on how the new generation in India sees Pakistan, Hindol Sengupta said that “mood” towards Pakistan changes as you travel across the country and the current generation is willing to make peace, or war, with Pakistan if that country wishes so.

“We are all for Aman Ki Asha; but we are not for Aman Ka Nasha!” Hindol Sengupta, quite eloquently, made his point that India’s approach towards Pakistan should depend on the nature of the action of Pakistan. India should engage with Pakistan, he said, and should boost trade and other partnerships, but we shouldn’t be willing “to make peace at all costs”.

What Can I Give?

Day Four had Srijan Pal Singh talking about the legacy and teachings of APJ Abdul Kalam. The session also includes the educationist Anand Kumar, who founded the Super 30 programme, which has helped several economically backward students achieve their dream of qualifying for the Indian Institute of Technology.

When the man, dubbed by Peoples Magazine as the “People’s Hero” took the stage, there was a wave of euphoria in the audience. Anand Kumar began the session talking about his father, who despite poverty managed to educate him. “When I was a kid, I had seen how my father tried to provide us education. He was deeply hurt by the fact that he was not able to attain education. My father knew the power of education. That is why he gave up our land but didn’t restrict our education,” he said.

As Anand Kumar took his seat, it was Srijan Pal Singh’s turn to talk to the audience about his time with APJ Abdul Kalam. It is a testament to the popularity of the late former president that so many people from different generations and various walks of life turned up to hear Singh talk about the “People’s President”. Singh, who was an aide to the late former president, is in the unique position to give us a first-hand account about APJ Abdul Kalam.

The engineer also credited the title of his book. What Can I Give? to Dr Kalam. In 2009, the duo was working on a speech celebrating a swamiji who had turned 102. Because Dr Kalam’s parents also lived for a long time (his dad was 98 when he passed away while his mother reached 100) he asked him what the key for people living so long was. He said ‘There’s only one key, he asks himself – What can I give? The swami fed and educated so many people. His conviction and spirit comes from the – What can I give?’”

Nawaznama

On Day Five, one of India’s best actors, Nawazuddin Siddiqui, landed in Delhi to promote his book, Nawaznama. Writer and journalist Rituparna Chatterjee, who is the co-writer of Nawaz’s book, joined him.

Siddiqui said the book was about his experiences in his village in UP, his acting education at the National School of Drama (NSD) in Delhi to his foray into Bollywood. “I will try to state the truth (mostly) in the book. I will be narrating my life indefinitely,” he said.

A piece of my heart

The first session on the final day of the Spring Fever 2016 saw the amphitheatre packed with booklovers and movie enthusiasts to listen to Emraan Hashmi and Sonali Bendre Behl tackle the problem of raising kids in this digital age. Hashmi also revealed the cover of his forthcoming book, The Kiss of Life. Co-written by Bilal Siddiqi, who was also in the panel, the book deals with how Hashmi’s son Ayaan beat cancer.

The session began with Sonali talking about how different this generation is compared to theirs. She said that this generation has easy access to technology and information, which is why parents must also adapt to the changing times. She admitted that she came from a very “middle-class Maharashtrian family” and that she didn’t even have a TV until she was in college. “We need to bring up our child in a digital age, but remember our roots - our roots are what ground us,” she said.

Speaking about his son’s tumor, Emraan Hashmi said that the psychological damage that cancer does to a family is so big. He admitted that he still felt like he needed to go for counselling. "There was a huge tumor the size of a season ball growing inside a three-year-old - my son,” said the Murder actor. He confessed that when he heard the news, he walked out the clinic and broke down. The usually flamboyant actor gave a somber account of how cancer affects a family.

Kitaabein with Gulzar

“My thoughts were simmering inside me like vapour simmers inside a covered utensil. When that cover was removed, my expressions flowed out from within!” Gulzar said during the last session of Spring Fever 2016. “Books trained me to read and be busy. There is nothing like reading books to spend quality time,” the poet and filmmaker said, adding, “A book has many layers. It opens up to its reader layer by layer!”

Delving into those early days when, as a young man, he used to spend his time reading books, Gulzar recounted: “My family had a shop. I was supposed to manage it. I would go to the shop and would sleep there during the night. There wasn’t much to do. It was then that I came to know of a bookshop whose owner used to lend out books. I used to borrow books, read them voraciously, and come back the next morning to borrow another. Confused and irritated, the bookshop owner gave me very thick book this time, in the hope that I would take many days to complete it and wouldn’t be back to bother him. That book was The Gardener, by Rabindranath Tagore. It changed my life!”

To you writers, he advised: “You have to be a sensitive person to become a writer. There are so many sounds all around us. It depends on how receptive you are. Allow those sounds to fill you,” adding, “Writing is not as instant as instant food . . . Story making is architectural. The idea of your story, its theme, is the land. You have to design and build the story over it.”

(Information culled from the Penguin Random House blog, randomhouseindia.wordpress.com. No express permission to republish this has been sought.)

The most interesting part of the event was the open-air library, where visitors could browse through the books from among 5,000 titles published by Penguin and Random House.

The challenge of contemporary history

Historian and writer Ramachandra Guha opened the festival with an exclusive preview of his forthcoming book, a collection of essays called Democrats and Dissenters. The book critically assesses the work of economist Amartya Sen and Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, and explores major political and cultural debates across India and the world.

Guha talked about the paradox that while India is the “most interesting country in the world,” we know so little about its contemporary history. He said there have been three great democratic revolutions – the French, the American and the Indian revolutions. While the Indian revolution maybe the most important, it is the least written about. This might be because it is the most recent and that it occurred in a continent which is not known for being a “beacon of liberty and freedom.”

“Indian history is a thriving, rich productive field, but much of it, in my view, too much of it focuses on the colonial period. That is from 1757 to Partition in 1947,” he said, adding that there has been an almost unhealthy obsession with colonialism. This means that our historians have neglected the period before and after colonialism.

Guha then proceeded to talk about the four major challenges that a contemporary history writer faces.

First, the reader of a contemporary history writer’s book was not a “passive recipient of the text.” The reader will have strong prejudices and opinions about the recent past, especially about political leaders. “The reader is a critical citizen. His or her ideological and social preferences, even before you offer your history, they know all about it. You may write a 500-page book based on careful research, but they’ll approach that book already knowing what this book about Nehru or Ambedkar is all about,” he said.

Second, the contemporary historian, like the reader, is also not free from prejudice and opinions.

Third is the density of sources. He claimed that because the British kept most of their files, there is so much material for colonial historians to use. “Our governments either don’t keep files or they shred them when they leave office. Even if they keep them, they do not transfer them to the national archives,” he added. Guha said historians need primary sources to work with. Unlike the colonial sources, the recent past sources were “scanty and imperfectly kept and sometimes not available at all.” Unlike most democratic countries, where the papers of leaders are properly archived and open to scholars, in India, the families of the leaders get the papers, which they do not share.

The fourth one, Guha said, is a “peculiarly Indian challenge.” It is to do with the disciplinary boundary in the Indian universities. “When the clock struck midnight on 14 August 1947, history ended and political science began.”

Talking about his book, Makers of Modern India, Guha said India is undergoing five revolutions simultaneously. A political revolution, where a society based on feudal elite moved to system where every citizen has a vote. A national revolution, where a nation ruled by foreigners we now have swaraj. An industrial revolution where an economy based largely on agriculture is becoming industrial. An urban revolution where settlement patterns based on villages are becoming city based. And, a social revolution where tradition hierarchy, particularly, on caste and gender are being challenged. Unlike other countries where these revolutions have staggered, India is undergoing these revolutions now. “We are extremely large and extremely diverse and we are undergoing these revolutions. That’s why as a historian, I am privileged to be born in India. I could spend five lifetimes writing about these five revolutions,” he said.

The author also took the time to talk about extremism. He said extremists talk the loudest and that they see the world in black and white. He added that this certitude prevented us from “understanding the complexity of our country.” Hindu extremism, he believes, is not new and that Hindus are “a majority with a minority complex.” While globally, Islamic terror was dangerous, Guha feels that Hindu fundamentalism is dangerous in India.

Incarnations: India in 50 Lives

On Day Two, author, historian, and professor Sunil Khilnani came out to present and discuss his most recent work, Incarnations – an account of 50 lives that have influenced the Indian civilization.

Khilnani started his talk with an anecdote. “Some four decades ago, a violent storm hit Sannati – a small village on the Bhima River in northern Karnataka. The roof of the village temple collapsed, and the image of the deity – Kalikambal – was crushed. The image had long stood on a large stone slab. As the workers cleared away the stone’s debris, the slab flipped over, and on the underside were inscriptions in the Brahmi script – fragments, archaeologists would later determine, of two rock edicts of the third century BC emperor, Ashoka. The subject of one of the buried edicts was, as it happens, the importance of respect for the beliefs of others. “As I reflected upon that edict in Sannati, I was struck by the historical irony: Ashoka’s optimistic words on religious tolerance had been literally turned upside down – cut up and repurposed as a platform for a Hindu goddess,” he said.

Khilnani recorded: “India’s past is an arena of ferocious contest, its dead heroes springing back to life and dispatched to the front-lines of equally ferocious contemporary cultural and political battles.”

It is in that context that Khilnani wants to “restore the individuals to their rightful places” because, as he poignantly begins his book by saying, “Indian history is a curiously unpeopled place. As usually told, it has dynasties, epochs, religions and castes – but not many individuals.”

Khilnani then proceeded, with a host of images, to offer the range of his book: It explores 50 lives across 2,500 years of Indian history – from the “moral preoccupations” of the Buddha to the “capitalistic” energy of Dhirubai Ambani, via famous, and not-so-famous, monarchs, artists, writers, thinkers, leaders, and freedom fighters.

“One of my criteria for inclusion [of these characters],” Khilnani said, “was the light old lives might shed on urgent issues of the present.” Championing the fact that India has always been a “messily hybrid, multi-ethnic, multi-religious place, where identity, the social order and religious convictions have always been in flux and open to challenge”, the author eloquently reminded the audience: “What has driven India forward is the role of individual dissent!”

Khilnani said that he had a “big list” of individuals to begin with and he had to select and omit – some unpopular selections being the lives of the forgotten Malik Ambar and Chidambaram Pillai, and a striking omission being that of Pandit Nehru. Dr. Khilnani explained in the introduction: “I have chosen to leave out some familiar names, to allow space to bring in a few others who should be more widely known – a choice with which I think one of the figures I have excluded, Nehru, would have agreed”.

Pakistan is in the eye of the beholder

Day Three saw five highly opinionated achievers taking to the stage. The panelists were: Shashi Tharoor, author and politician; TCA Raghavan, author and former High Commissioner to Pakistan; Taslima Nasreen, author and activist; Hindol Sengupta, author and journalist; and Neeraj Kumar, author and former Commissioner of Delhi Police. Joining them through a video recording was Husain Haqqani, author and Pakistani diplomat.

“Every country is only in the eye of the beholder!” Husain Haqqani said, underscoring the point that each country rises and falls in other people’s eyes according to the experiences they have had with the country. “What we [in Pakistan] have to figure out is how Pakistan can live at peace with itself and with its neighbors,” Haqqani added.

When Shashi Tharoor starts to speak, one hardly remembers that he is a former diplomat or, for that matter, a member of a particular political party. He outgrows limitations to speak his mind, and he speaks well. “I tend to behold Pakistan with a heart of a dove and with a head of a hawk!” Shashi Tharoor began. “Kashmir is not the core problem... the real problem between India and Pakistan is the nature of the Pakistani state. In India, the state has the army; in Pakistan, the army has the state,” he said.

TCA Raghavan pointed out that Pakistan is a country with 200 million people who possess a “very strong sense of themselves”, and, therefore, we shouldn’t underestimate them, or just rely on state policies. “Whatever change might come about is largely not going to be because of external factors, or because of India. It’s going to be come about from what they do with themselves and how they imagine their future,” Raghavan reminded the audience.

Taslima Nasreen writes powerfully but speaks softly, and takes her time to pace herself. When asked to present her thoughts on Pakistan, the Bangladeshi author, who now lives in the US, shared with the audience the poignant anecdote when, during the 1971 war, Pakistani army raided her home, amongst many other homes in Bangladesh. “They tied my father to a coconut tree and they tortured him... I heard the sound of heavy boots in the room I was sleeping in... they looted our house... and burnt villages.”

As a hardcore critic of blind faith, Taslima Nasreen didn’t pull her punches yet again: “If you create a country on the basis of religion, that country becomes a fundamentalist country”.

As the former Commissioner of Police and investigator of numerous terror attacks in India, Neeraj Kumar, immediately outlined the laxity on the part of India: “In each one of the them [the terror attacks] it was conclusively proven that the establishment [in Pakistan] had a role... We are always reacting [to what Pakistan does].”

Much like an investigator, Neeraj Kumar underscored the pattern of the terror attacks, and, thus, the motives: “They have the clear target to attack the great icons of the country to show that nothing is safe... and they adopt the most insidious strategy.”

Much like Husain Haqqani, Hindol Sengupta began by drawing a clear line between the state of Pakistan and the people of Pakistan: “Friendship between the individuals in India and Pakistan is different from the state called Pakistan. You have to distinguish.”

Commenting on how the new generation in India sees Pakistan, Hindol Sengupta said that “mood” towards Pakistan changes as you travel across the country and the current generation is willing to make peace, or war, with Pakistan if that country wishes so.

“We are all for Aman Ki Asha; but we are not for Aman Ka Nasha!” Hindol Sengupta, quite eloquently, made his point that India’s approach towards Pakistan should depend on the nature of the action of Pakistan. India should engage with Pakistan, he said, and should boost trade and other partnerships, but we shouldn’t be willing “to make peace at all costs”.

What Can I Give?

Day Four had Srijan Pal Singh talking about the legacy and teachings of APJ Abdul Kalam. The session also includes the educationist Anand Kumar, who founded the Super 30 programme, which has helped several economically backward students achieve their dream of qualifying for the Indian Institute of Technology.

When the man, dubbed by Peoples Magazine as the “People’s Hero” took the stage, there was a wave of euphoria in the audience. Anand Kumar began the session talking about his father, who despite poverty managed to educate him. “When I was a kid, I had seen how my father tried to provide us education. He was deeply hurt by the fact that he was not able to attain education. My father knew the power of education. That is why he gave up our land but didn’t restrict our education,” he said.

As Anand Kumar took his seat, it was Srijan Pal Singh’s turn to talk to the audience about his time with APJ Abdul Kalam. It is a testament to the popularity of the late former president that so many people from different generations and various walks of life turned up to hear Singh talk about the “People’s President”. Singh, who was an aide to the late former president, is in the unique position to give us a first-hand account about APJ Abdul Kalam.

The engineer also credited the title of his book. What Can I Give? to Dr Kalam. In 2009, the duo was working on a speech celebrating a swamiji who had turned 102. Because Dr Kalam’s parents also lived for a long time (his dad was 98 when he passed away while his mother reached 100) he asked him what the key for people living so long was. He said ‘There’s only one key, he asks himself – What can I give? The swami fed and educated so many people. His conviction and spirit comes from the – What can I give?’”

Nawaznama

On Day Five, one of India’s best actors, Nawazuddin Siddiqui, landed in Delhi to promote his book, Nawaznama. Writer and journalist Rituparna Chatterjee, who is the co-writer of Nawaz’s book, joined him.

Siddiqui said the book was about his experiences in his village in UP, his acting education at the National School of Drama (NSD) in Delhi to his foray into Bollywood. “I will try to state the truth (mostly) in the book. I will be narrating my life indefinitely,” he said.

A piece of my heart

The first session on the final day of the Spring Fever 2016 saw the amphitheatre packed with booklovers and movie enthusiasts to listen to Emraan Hashmi and Sonali Bendre Behl tackle the problem of raising kids in this digital age. Hashmi also revealed the cover of his forthcoming book, The Kiss of Life. Co-written by Bilal Siddiqi, who was also in the panel, the book deals with how Hashmi’s son Ayaan beat cancer.

The session began with Sonali talking about how different this generation is compared to theirs. She said that this generation has easy access to technology and information, which is why parents must also adapt to the changing times. She admitted that she came from a very “middle-class Maharashtrian family” and that she didn’t even have a TV until she was in college. “We need to bring up our child in a digital age, but remember our roots - our roots are what ground us,” she said.

Speaking about his son’s tumor, Emraan Hashmi said that the psychological damage that cancer does to a family is so big. He admitted that he still felt like he needed to go for counselling. "There was a huge tumor the size of a season ball growing inside a three-year-old - my son,” said the Murder actor. He confessed that when he heard the news, he walked out the clinic and broke down. The usually flamboyant actor gave a somber account of how cancer affects a family.

Kitaabein with Gulzar

“My thoughts were simmering inside me like vapour simmers inside a covered utensil. When that cover was removed, my expressions flowed out from within!” Gulzar said during the last session of Spring Fever 2016. “Books trained me to read and be busy. There is nothing like reading books to spend quality time,” the poet and filmmaker said, adding, “A book has many layers. It opens up to its reader layer by layer!”

Delving into those early days when, as a young man, he used to spend his time reading books, Gulzar recounted: “My family had a shop. I was supposed to manage it. I would go to the shop and would sleep there during the night. There wasn’t much to do. It was then that I came to know of a bookshop whose owner used to lend out books. I used to borrow books, read them voraciously, and come back the next morning to borrow another. Confused and irritated, the bookshop owner gave me very thick book this time, in the hope that I would take many days to complete it and wouldn’t be back to bother him. That book was The Gardener, by Rabindranath Tagore. It changed my life!”

To you writers, he advised: “You have to be a sensitive person to become a writer. There are so many sounds all around us. It depends on how receptive you are. Allow those sounds to fill you,” adding, “Writing is not as instant as instant food . . . Story making is architectural. The idea of your story, its theme, is the land. You have to design and build the story over it.”

(Information culled from the Penguin Random House blog, randomhouseindia.wordpress.com. No express permission to republish this has been sought.)

Published on March 23, 2016 01:37

March 20, 2016

The Poisonwood Bible

Published on March 20, 2016 05:57

March 18, 2016

Gypsy Boy

Published on March 18, 2016 05:47

March 12, 2016

Spotlight

What I like most about Spotlight, which received the Oscar for Best Picture of 2016, is the restrain. It refuses to play to the gallery, it refuses to veer into flashback, and it doesn’t want to resort into moralising. It just wants to narrate the series of events as it happened, doggedly, and it plays out like a golden-age thriller. There were not even big emotional scenes, except the one where Mark Ruffalo showcased his action chops.

And, for someone who has worked and loved working in the newsroom, the film was exciting to watch. And small scenes stood out, like when the editor asks the Metro reporter to bury the news, or when he corrects a copy, saying, there is another adjectives. Yeah, adjectives were the demons we fought every day, or rather, every night.

And, for someone who has worked and loved working in the newsroom, the film was exciting to watch. And small scenes stood out, like when the editor asks the Metro reporter to bury the news, or when he corrects a copy, saying, there is another adjectives. Yeah, adjectives were the demons we fought every day, or rather, every night.

Published on March 12, 2016 00:36

March 11, 2016

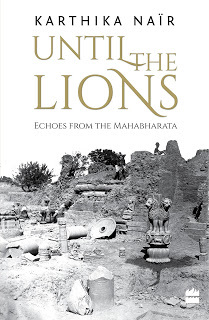

Until the Lions: Echoes from the Mahabharata

I don’t know how to react to this book by Karthika Naïr. A friend gave it to me recently, saying, as a poet, and a Mahabharata aficionado, I must read it. I did. I love the name. I understand the conceit – a feminist retelling of the greatest tale ever told (The title borrows from the famous African proverb –‘Until the lion has his or her own storyteller, the hunter will always have the best part of the story.’). I have no problems with it. Apart from the usual suspects, Naïr has amassed some less know characters, which is always nice. There are 19 voices, telling the tale from their point of view, complaining, accusing, judging, and making sense of the reality…

I don’t know how to react to this book by Karthika Naïr. A friend gave it to me recently, saying, as a poet, and a Mahabharata aficionado, I must read it. I did. I love the name. I understand the conceit – a feminist retelling of the greatest tale ever told (The title borrows from the famous African proverb –‘Until the lion has his or her own storyteller, the hunter will always have the best part of the story.’). I have no problems with it. Apart from the usual suspects, Naïr has amassed some less know characters, which is always nice. There are 19 voices, telling the tale from their point of view, complaining, accusing, judging, and making sense of the reality… There are some voices I really admired, like Ulupi mourning the beheading of Aravan. This may be because I have been thinking about the same story. Or, Jaratkaru, Astika’s mother, who would later be deified as Manasa in Eastern India; again, a character I have been thinking about a lot.

But as I read and reread some portions, I don’t know what to say. Some of the lines are pure brilliance. They leap out of the pages and hit you, in a good way, in a way good poetry can, and then there are lines and lines of banal meandering, just plain narrative in free verse, without a shred of poetry. How could this happen?

Simply, this is the circle I encountered. There are some brilliant lines, with some brilliant insight, brilliant images, a perfect rendering of the emotion, and you think, you have arrived at the right spot. And then, the narrative slips. It goes to plain storytelling. At one level, I understand. As far I can guess, the book was primarily written for a western audience, who would need to be clued in into the narrative, which is already disjoined. So, the storytelling fills the gap. But poetry it is not.

So, what do you do? I remember Bhartrihari, who wrote, be like a swan, which swims in the water, but drinks only the milk of it, not the dirt. So, this is what I did. I took a marker pen and underlined the lines I liked. It’s almost half of the book. The next time, I will read these underlined sentences and ignore the rest.

Oh, I like the cover, featuring, what I assume, a digging site at Sarnath during the Raj.

(And, I am remembering Amruta Patil’s Adi Parva, also published by HarperCollins. This is the best Mahabharata retelling in the recent years, by any standard.)

Published on March 11, 2016 04:18

The Rise of the Indian Short Story

This story begins with a caveat. This write has a collection of short stories, which he is trying to sell to a name publisher for the last two years (He is old-school. He doesn’t want to self-publish!). He even hired a literary agent (These days most name publishers want to receive manuscripts from literary agents. It helps the publisher determine the quality and market for a particular book.). Then the agent got back to him saying that while she thought the stories were good, no one was interested, because short stories do not sell. Publishers believe all people want to read are bulky Great Indian Novels. Novels are nominated for awards and they sell well. (Remember the bestselling phenomenon that was the 1,300-page tome called A Suitable Boy?)

The writer could not abide by this verdict. The argument was just not valid. When we discuss changing reading habits (moving from printed pages to digital screens) and constantly diminishing attention span, short story is the only format that can deal with these changes. As the name suggests, it is short and it tells a story within a short time.

Yes, it’s true, since 1980s, when Salman Rushdie put Indian literature in the world map, with the publication of Midnight’s Children, novels have been the raison d’être Indian English language publishing, relegating the short story genre to the backburner. Yet, short stories survived, and now, in the last two years, the genre is making a comeback.

Just look at two of the best-reviewed books in the market right now, Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar’s The Adivasi will not Dance and Mahesh Rao’s One Point Two Billion. Both are short story collections, but with a twist. Shekhar’s stories focus on tribal characters from Jharkhand. Each of Rao’s stories is set in a different Indian state, from Assam to Delhi. The title refers to the population of India.

Then we have Kanishk Tharoor, the talented son of Shashi Tharoor, who was the toast of the recently concluded Jaipur Literature Festival, for his Swimmer Among the Stars: Stories. The book is yet to hit the market and it has already received enthusiastic reviews.

The genre received the biggest shot in the arm when David Davidar, the co-founder of Aleph Book Company edited A Clutch of Indian Masterpieces: Extraordinary Short Stories from the 19th Century to the Present in 2014. Now, Aleph is publishing Arunava Sinha’s translations of The Greatest Bengali Stories Ever Told.

Short stories were always a part of our literature, especially in regional writing. Today, we remember Tagore (The Hungry Stone), Premchand (Shatranj Ke Khiladi), Vaikam Muhammed Basheer, Mahasweta Devi (Draupadi), Manto (Toba Tek Singh) and Ishmat Chugtai (Lihaaf) for their short fiction.

Examples abound in English as well. We have all read the magical stories of RK Narayan (Malgudi Days) and Ruskin Bond (Our Trees Still Grow in Dehra).

Jhumpa Lahiri shot to international fame after her short collection Interpreter of Maladies was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2000. Even Aravind Adiga published a short story collection (Between the Assassinations) after his Booker Prize in 2008.

The writer could not abide by this verdict. The argument was just not valid. When we discuss changing reading habits (moving from printed pages to digital screens) and constantly diminishing attention span, short story is the only format that can deal with these changes. As the name suggests, it is short and it tells a story within a short time.

Yes, it’s true, since 1980s, when Salman Rushdie put Indian literature in the world map, with the publication of Midnight’s Children, novels have been the raison d’être Indian English language publishing, relegating the short story genre to the backburner. Yet, short stories survived, and now, in the last two years, the genre is making a comeback.

Just look at two of the best-reviewed books in the market right now, Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar’s The Adivasi will not Dance and Mahesh Rao’s One Point Two Billion. Both are short story collections, but with a twist. Shekhar’s stories focus on tribal characters from Jharkhand. Each of Rao’s stories is set in a different Indian state, from Assam to Delhi. The title refers to the population of India.

Then we have Kanishk Tharoor, the talented son of Shashi Tharoor, who was the toast of the recently concluded Jaipur Literature Festival, for his Swimmer Among the Stars: Stories. The book is yet to hit the market and it has already received enthusiastic reviews.

The genre received the biggest shot in the arm when David Davidar, the co-founder of Aleph Book Company edited A Clutch of Indian Masterpieces: Extraordinary Short Stories from the 19th Century to the Present in 2014. Now, Aleph is publishing Arunava Sinha’s translations of The Greatest Bengali Stories Ever Told.

Short stories were always a part of our literature, especially in regional writing. Today, we remember Tagore (The Hungry Stone), Premchand (Shatranj Ke Khiladi), Vaikam Muhammed Basheer, Mahasweta Devi (Draupadi), Manto (Toba Tek Singh) and Ishmat Chugtai (Lihaaf) for their short fiction.

Examples abound in English as well. We have all read the magical stories of RK Narayan (Malgudi Days) and Ruskin Bond (Our Trees Still Grow in Dehra).

Jhumpa Lahiri shot to international fame after her short collection Interpreter of Maladies was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2000. Even Aravind Adiga published a short story collection (Between the Assassinations) after his Booker Prize in 2008.

Published on March 11, 2016 03:31