Maryn McKenna's Blog, page 18

September 26, 2012

Why The New Coronavirus Unnerves Public Health: Remembering SARS

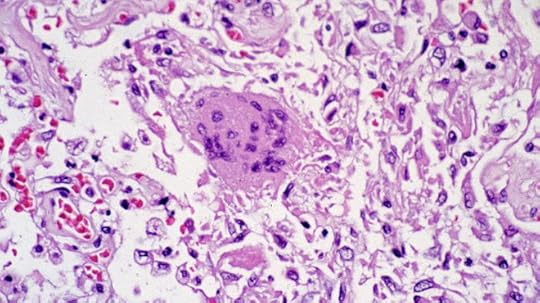

Lung tissue containing the original SARS coronavirus (CDC, 2003)

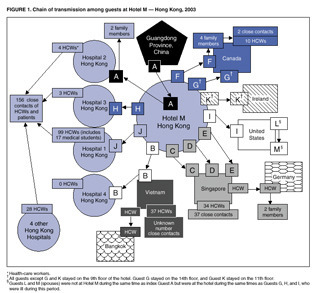

On Feb. 21, 2003, a 65-year-old physician who lived in the Chinese province that abuts Hong Kong crossed into the territory surrounding the city and checked into a hotel in Kowloon. He was given a room on the 9th floor. Sometime during his stay — no one has ever fully traced his path — he encountered roughly a dozen other people; most of them were hotel guests whose rooms were on the same floor, but some were staying on other floors, and some were visitors to events there. The physician had been sick for a week with symptoms that had started like the flu, but were turning into pneumonia, and the next day, he checked out of the hotel and went to a Hong Kong hospital. Before the end of the day, he died.

In the next few days, the people who had crossed paths with the physician left the hotel. Most of them were visitors to the special administrative region: Hong Kong is not only a port and transit hub, but a business and shopping destination for much of the Pacific Rim. They went to Vietnam, Singapore, Canada, and Ireland. As they traveled, some of them started to feel as though they had picked up the flu.

The CDC’s 2003 diagram of the first SARS cases outside China.

Within a month, health authorities in 14 countries had identified more than 1,300 cases of respiratory illness that all traced back to those brief encounters somewhere in the hotel. Within five months, the illness — dubbed SARS, for severe acute respiratory syndrome — had caused 8,098 illnesses, and 774 deaths, in 26 countries around the world.

SARS (which had been brewing in China for months but never previously escaped) was caused by a novel coronavirus, for which there was no uncomplicated treatment and no vaccine, and despite being seeded in a very small group of people, it spread rapidly around the world. That goes a long way to explain why health authorities are so unnerved now by the identification of another novel coronavirus, which has been identified in a part of the world where millions of people are about to converge, mingle and leave.

To recap:

The novel virus apparently has been responsible for a very few illnesses and deaths in the past few weeks. It has caused the illness of one man who visited Saudi Arabia but now is hospitalized in England, and an almost-identical virus has caused the death of one man who was a Saudi resident. There has been a report of a second death in Saudi, and concerns have been raised about an outbreak of respiratory illness in Jordan (which shares a border with Saudi Arabia) in April, and of the illnesses last night of five people who were put into isolation in Denmark.

The World Health Organization has issued an alert and written a preliminary case definition, which because it is early in this episode is so loose — involving fever, cough and either travel to Qatar or Saudi Arabia, or contact with someone who did — that it is likely to turn up many unrelated cases that could temporarily inflate the numbers.

The virus is so new that it has not been named officially, but as of last night it had been partially sequenced and aligned with other coronoviruses including the SARS virus. The dendrogram, and information about lab options for molecular diagnostics, were posted last night by the UK’s Health Protection Agency. (Soon afterward, virologist and commentator Vincent Racaniello cautioned that Koch’s postulates haven’t yet been fulfilled, underlining that the virus has been isolated from people with respiratory symptoms, but has not yet been proven to cause those symptoms.)

And the WHO’s spokesman on the emerging virus, Gregory Hartl, has repeatedly reminded media covering the story that (as he said in a briefing taped Tuesday) “this is not SARS, it will not become SARS, it is not SARS-like” — a point that was not necessarily meant to be a reassurance, since he added, “It is distinct from SARS at least in the fact that we’ve seen so far, it causes very rapid renal failure.”

The concern underlying these developments is that exposure to the new virus seems to have occurred only or primarily in Saudi Arabia, which houses Mecca, the physical heart of Islam — and which, next month, will be the center of the worldwide annual pilgrimage known as the Hajj. The Hajj brings more than 2 million people to the country, in extraordinarily crowded conditions, and when those pilgrims leave, they disperse all over the world.

The spread of disease during the Hajj has always been a concern (discussed, for instance, in this UK document from 2005, when avian flu H5N1 was a cross-border threat), and the Saudi authorities have always taken it seriously, including requiring that pilgrims be vaccinated in order to be granted a visa. According to news reports today, they are ramping up scrutiny of visitors, who have already begun arriving: The first official day of the pilgrimage season this year is tomorrow, Sept. 27, though the central observances in Mecca do not begin until Oct. 24.

Given the periodically flaring tensions between the Islamic world and the West — exemplified most recently by the attack on the US embassy in Libya — preventing the Hajj from being identified with the spread of a disease is a priority not just for health authorities, but for governments. But a month is a long lead time in modern public health, even given how fast diseases such as SARS can spread. Meanwhile, here are some key sources to watch for news:

The WHO’s page

The HPA’s excellent list of resources

The blogs of Mike Coston and Crawford Kilian, who do a phenomenal and completely unrecompensed job of keeping track of international developments in public health.

It is also a good idea to watch for any stories by Helen Branswell of the Canadian Press, one of very few reporters who covered SARS almost a decade ago and is still on the beat (with this story, for instance). I also covered SARS, and I’ll do my best to update here.

Almost immediate update: As an example of how fast things are moving, just as I hit the button on this, Agence France Presse posted a report that the five Danish cases have been diagnosed with influenza B.

SARS image, PHIL, CDC

September 23, 2012

Superbug Summer Books: The Best Science Writing Online 2012

I’m cheating a bit here, since summer ended before dawn yesterday. But for the last entry in Superbug Summer Books, I wanted to leave you with something recent, and something rich, and today’s pick qualifies twice over: It was released just last week, and it is full — stuffed — with excellent science writing, more than enough to keep you reading until I pick up this intermittent book feature, in adapted form, later this fall.

“The Best Science Writing Online 2012” (Scientific American/Farrar, Straus and Giroux) is the latest in a series begun in 2006 by Bora Zivkovic, now the editor of Scientific American‘s blog platform, and a series of guest editors. The series was originally dubbed “The Open Laboratory” and published independently. This year’s iteration has been brought forward by a major publisher, the new Scientific American imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, with all the extra market legitimacy that suggests.

The collection serves several purposes. It elevates the best science blogging — which is in many cases the best science writing being done today — to the attention of new audiences, and it confers some permanence on a writing form that risks evanescence. As Bora writes in the preface, inclusion in the annual collection also has become a genre-crossing distinction:

The collection serves several purposes. It elevates the best science blogging — which is in many cases the best science writing being done today — to the attention of new audiences, and it confers some permanence on a writing form that risks evanescence. As Bora writes in the preface, inclusion in the annual collection also has become a genre-crossing distinction:

Bloggers with entries included in the collections proudly sport the buttons on the sidebars of their blogs. Those science bloggers who are also professional researchers list their inclusion in the anthology as a publication on their resumes. Bloggers who are also active researchers list it in the “outreach” section of their CVs…It is seen as a bridge between the online and offline worlds.

This year’s guest editor is Jennifer Ouellette, author of the blog Cocktail Party Physics and of several books, most recently “The Calculus Diaries: How Math Can Help You Lose Weight, Win in Vegas, and Survive a Zombie Apocalypse” (Penguin). In her introduction, she says,

I am struck anew by the sheer diversity in voice, style, subject matter, and creativity that one finds across the blogosphere, and the science blogosphere in particular. There is poetry. Savvy reportage and critical analysis of new scientific papers. In-depth profiles. Personal reflections. Humor. Thoughtful commentary on science and social issues. Careful explication of complex scientific concepts written in accessible language. And yes, there are long-form features and investigative journalism. Above all, there are stories — drawn from history, popular culture, the laboratory, and personal experiences.

The writes represented in the anthology include some of the stars of science writing today, including Maggie Koerth-Baker of BoingBoing and Ed Yong and Carl Zimmer from the Discover network, along with my Wired colleagues Deborah Blum, on the poisonous possibilities of carbon dioxide; David Dobbs, on how much of science is lost forever behind the paywalls of journals; and Brian Switek, on the dodo. (Disclosure: As you’ll see if you study the cover image above, I am in the anthology also, for this post on polio eradication.)

But the real pleasure of this anthology — and why I hope you’ll read it — is the chance to discover writers whom you may not have heard of, because they do not benefit from the enormous readership of networks such as ours here. There are more than 50 writers in the collection, so I cannot call them all out, though they all deserve it. But I urge you not to miss:

T. DeLene Beeland’s elegy for the “church forests” of Ethiopia

Aatish Bhatia’s straight-faced exploration of the fluid dynamics of sperm (with sketches!)

Krystal D’Costa’s analysis of the brand supremacy of pirates

Kimberly Gerson’s sympathetic but clear-eyed explanation of how humans failed Romeo, a wolf who sought his pack among dogs

Matthew Hartings on the molecular chemistry of gin and tonics

Karen James’ breathtaking reportage from the last launch of the space shuttle Atlantis

David Manly on the science, and the experience, of being an identical twin

Puff the Mutant Dragon’s chilling unfolding of the effects of organophosphate pesticides

Cassie Rodenberg on how narcopelsy is like addiction

Richard F. Wintle’s parsing of genome sequencing, and Shakespeare.

There’s also poetry, penises, staircases, airplanes and a fairy tale. Buy it. It is worth your time.

This is the last entry in an intermittent series I ran during summer 2012 about books I liked and thought readers should take a look at. In coming months, I’ll continue this book feature about twice per month. You can find past and future books at #SBSBooks on Twitter.

September 17, 2012

The ‘NIH Superbug’: A New Case, And An Overlooked Resource

News, via the Washington Post‘s hard-working health reporter Brian Vastag: After 6 months with no cases, carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella has surfaced again at the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health, and has killed a boy from Minnesota who came to the specialty hospital after a bone-marrow transplant meant to address an immune deficiency. This sad event makes the boy the 19th patient to contract the extremely resistant hospital organism, and the 12th to die from it, since the outbreak began.

You can find here my last post analyzing this outbreak (which was originally reported by the Post following a write-up by NIH staff in the journal Science Translational Medicine). I’m looping back to the subject not just because of this new death, but also to add a few new publications to the discussion, one of them mine.

You might remember from the initial coverage (including great blog posts by physicians Judy Stone and Eli Perencevich) that CRKP or KPC is a challenge for several reasons. First, it is extremely drug-resistant, responding to only a few remaining antibiotics. Second, it is extremely persistent in the environment, able to live on inorganic, low-nutrient surfaces such as metals and plastics. And, third, it can be harbored asymptomatically in patients’ guts, meaning that patients can bring in into a hospital, or acquire it in one hospital and take it to another, without it being detected — or at least, not until an outbreak begins.

There were several papers about CRKP during the ICAAC meeting last week. Some were on early-stage antibiotic compounds that might work, if they continue to progress through trials. But several looked at how widely distributed the organism might be. Those made it clear that, as I said last month, CRKP is everywhere — an emergency in slow motion, happening all around us, all the time.

A survey of patients on ventilators in hospitals and long-term care facilities in Maryland (where NIH is located) found the highly resistant organism in 6 percent of patients and 25 percent of facilities. (JK Johnson et al.)

A similar survey in Indiana found that over 14 months, 14 Indiana medical centers housed 71 patients carrying carbapenem-resistant organisms, 79 percent of which were KPC. (K. Bush et al.)

And a study conducted in Cleveland — where the VA hospital says it experienced a 2-year KPC outbreak from 2008-10 — found the gene that confers resistance in CRKP (blaKPC) moving into other organisms as well. (F. Perez et al.)

So how do hospitals combat this threat? By coincidence, I talk about this in my latest column for Scientific American, which is in the September issue and has just gone live on the web. It turns out that the key to controlling CRKP and similar organisms may require turning the hospital hierarchy upside-down — because the key personnel for eliminating these resistant bacteria turn out to be not the highly paid preventionists, but the building services personnel. Or, bluntly, the janitors. From SciAm:

Just a few years ago the poster bug for nasty bacteria that attack patients in hospitals was MRSA, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Because MRSA clings to the skin, the chief strategy for limiting its spread was thorough hand washing. Now, however, the most dangerous bacteria are the ones that survive on inorganic surfaces such as keyboards, bed rails and privacy curtains. To get rid of these germs, hospitals must rely on the staff members who know every nook and cranny in each room, as well as which cleaning products contain which chemical compounds…

“This is the level in the hospital hierarchy where you have the least investment, the least status and the least respect,” says Jan Patterson, president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Traditionally, medical centers regard janitors as disposable workers—hard to train because their first language may not be English and not worth training because they may not stay long in their jobs.

The piece discusses a project, the “Clean Team,” that was launched by NYU Langone Medical Center after KPC began making inroads there in the early 2000s. Clean Team relies on something that most hospital staff don’t think about: When they go into a room, they are focused on a patient, but the janitors focus on everything around the patient, from the counter to the keyboards to the bed curtains and the doorknobs. The project capitalizes on that granular knowledge by pairing janitors with infection preventionists and charge nurses, making them equal partners (with people who would otherwise be far above them in the professional hierarchy) and scoring them all up — or down — on how well their joint team performs.

For another approach to the same problem — coming to grips with how crucial low-status, high-turnover workers are to a hospital’s success — take a look at this video, filmed by the Illinois Department of Public Health. Its title is a message that, in the era of CRKP, hospitals need to hear: “Not Just a Maid Service.”

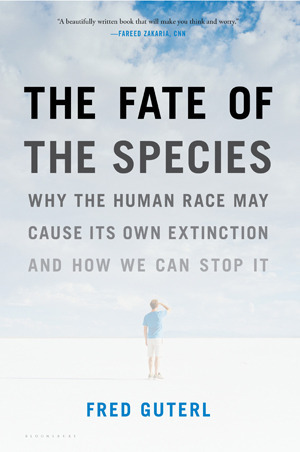

Superbug Summer Books:The Fate Of The Species

I confess: It can get lonely sometimes, being Scary Disease Girl. The universe of people who are deeply invested disease geeks is passionate (thank you, constant readers) but it isn’t that large. And let’s face it, keen interest in things that could bring an end to civilization as we know it — hitherto-unknown pathogens, rampant antimicrobial resistance, nanotechnology run amok — isn’t like to earn repeat invitations to most dinner parties.

So you can imagine how I welcomed the publication of Fred Guterl’s new book, “The Fate of the Species: Why The Human Race May Cause Its Own Extinction And How We Can Stop It” (Bloomsbury), a lean and thoughtful exploration of the possible impact on humankind of scary diseases, and many other potentially bleak futures. In a series of deeply reported what-if essays, Guterl explores the worst-case scenarios that climate change, species loss, and viruses both real and digital might bring — and what steps we might take now to avert these imagined but plausible outcomes.

A necessary disclosure: Guterl is the executive editor of Scientific American, where I am a columnist on contract. But the book didn’t come to me as a result of that relationship; it was sent to me by a publicist who noticed this books series and had no notion of our connection.

For the latest installment of Superbug Summer Books, I talked to Guterl by phone and edited and condensed our chat.

Wired: Why did you choose to spend a couple of years in the company of plagues and disasters? Or, put another way, why did you write this book?

Wired: Why did you choose to spend a couple of years in the company of plagues and disasters? Or, put another way, why did you write this book?

Fred Guterl: I get asked that question a lot (laughs). The things that I’ve been covering in the last 10 or 15 years tend to have an apocalyptic overtone – that is, the backdrop to the story is the possibility that things could go really wrong. You hear this enough, and you start thinking: “Well, what if?”

For instance, I was talking to an ecologist from the Santa Fe Institute, Jennifer Dunn, about how rapidly the human population has been rising. You know, we have 7 billion people now; when my father was born, there were fewer than two billion. The UN has this nice predictive curve that goes up to 10 billion and then levels off. And she said, “You know, that’s not what populations do. They don’t rise really quickly and then reach a steady state at the peak. They crash.” So then I thought, “Well, what could cause a correction?” And that leads to all the scenarios that I came up with.

Wired: In each chapter, you take one major potential threat, and you perform a thought experiment. You start with things which actually happened that didn’t go well — but didn’t go apocalyptically badly — and then push it a little bit further?

Guterl: I like the phrase “thought experiment,” because that’s what this is. I’m not making predictions. For instance, I start with the 2009 flu pandemic. This thing caught us with our pants down – and those are not my words, but the words of Robert Webster, the very distinguished flu virologist. He said: “We were completely surprised by this. It was just dumb luck that the virus was mild. And if it hadn’t been mild, it could have caused many, many deaths.” And when I say many, many — you know this — the 1918 flu caused 50 to 100 million deaths depending on how you count them. The population in 1918 was 1-2 billion and now we’re more than three times bigger. A simple extrapolation would put that at hundreds of millions of deaths, for a virus that had the 1918 mortality rate. Then take the mortality rate of the H5N1 bird flu, which is 60 percent. That would cause staggering losses.

Wired: How did you pick the examples, or thought experiments, that you did?

Guterl: You can report only so far, and then you have to make an informed guess of what is plausible. But in each case I tried to find people who have thought this stuff through, who have thought about what could really go wrong, and exactly how it would go wrong, and why it would happen in that way. It was kind of eerie; it reminded me of the discussions that went on during the Cold War, when people were considering what to do in case of mass casualties — when kids had to practice ducking under the desk, and people were told, “If you see a mushroom cloud don’t look at it.”

Wired: When people see my byline, they assume that their reaction to the story may well be, “Oh God, oh God, we’re all going to die.” (Which sometimes is true.) I’ll admit, eliciting that reaction from your audience – or experiencing it yourself when you’re reporting – can be a psychological burden after a while. So I’m wondering how you lived with that as you were working on this book, pressing on to the next most awful scenario.

Guterl: As I was writing this book, I was at Newsweek, and Newsweek was disintegrating around me, so there was a whiff of apocalypse in the air. I left Newsweek, I started at Scientific American, I was writing the book — it was a very busy time in my life. There were a lot of good things going on, but at the same time, it was tough. And this was tough to write.

When you are trying to write a book, you follow your curiosity. You are thinking, “Well, what would happen? And then what if that happened? How would that play out?” When I started finding the answers, I kind of pulled back a little bit. I didn’t want to write a book where every chapter ends with shoveling mass graves. So in some of the chapters, I actually didn’t go as far as I thought I would have. But there were times when people would say, “So, what’s your book about?” And I would start talking, and I would see the look on their faces as I was telling them about a virus that could go from one end of the world to the other, and the bodies that would be piling up in the streets. After that, they either really wanted to read the book, or they really didn’t want to.

Wired: I’m imagining you going deeper and deeper into these scenarios, and then getting to your last chapter, where you say: “But look! There might be some ways that we can save ourselves.” It must have been a relief. But given everything that leads up to it, do you actually have any confidence that these solutions could be achieved? Some of the things you talk about aren’t not necessarily complicated, but they require a kind of open-eyed assessment and political will that are in somewhat short supply these days.

Guterl: I think they are possible, and I think they are easier to think about when you think of them as technology problems. I don’t think anything is just a technology problem. Climate change, for instance, is not something that you could say technology will solve on its own. But I think if you think about them that way, then there’s hope. If you think about everything being a political question then I just start to get really depressed. We’re better at building things, I think, than we are at making sweeping political change. So if you focus on that then I think it’s easier to be optimistic. Which of course leaves me open to being accused of being naive, which is the drawback of being optimistic. But nevertheless, I am.

credit Brian Ach

Wired: When I was reading the book, I kept thinking of Robert Frost: “Some say the world will end in fire/ Some say in ice.” I wonder: Out of everything you examined, do you have a favorite apocalyptic scenario – or maybe it’s better to say, one that you think is most likely?

Guterl: I don’t have a favorite. But the one that was most surprising to me is the possibility of malware bringing down the Internet. We think of the Internet as being something pretty benign, and we base our global economy on it. We don’t think of computer programming and artificial intelligence as being necessarily bad. But the kinds of things that are possible now, and are becoming more possible, when you start making software that can act on its own, with a high degree of intelligence – and the way we’re giving over our decision-making as a result – that was unnerving to me.

Wired: As we’ve talked about, most of what you write about is – potentially – dire. So I’m wondering if there’s anything you explored for the book that has caused you to live your life differently in any way.

Guterl: No — but I’m a very lazy person. What I should do, maybe, for the sake of my family, is become more of a survivalist and start stocking up on things that we would need in a disaster. But then I think, “Well, we are in this together.” I think I’ve learned to value human connection more than anything else. It’s really important, connecting with people — professionally, your neighbors, your family. I didn’t write this into the book, but it’s the main thing that I’ve thought about, the last couple of years.

This is part of an intermittent series I’m running this summer about books I like and think you should take a look at. Some of the books are directly related to this blog’s core topics; others I just think are cool. You can find my picks at #SBSBooks on Twitter.

September 13, 2012

Drug Resistance in Food: Chicken, Shrimp, Even Lettuce (ICAAC 4)

A final post from the ICAAC meeting, which concluded at one end of the Moscone Center in San Francisco Wednesday just as the Apple iPhone 5 launch was beginning at the building’s other end. (Definitely a crossing of geek streams.)

There’s far too much going on at a meeting like this to cover everything. So what emerges, as journalists move around the session rooms and exhibit floors, are stories regarding whatever caught a reporter’s eye based on his or her existing interests and news sense.

What caught my eye was a lot of research into foodborne illness, and particularly into the possibility of food being a reservoir for antibiotic resistance (which, constant readers will know, is something I’m interested in).

So, a quick run through some of the many presentations on this topic:

First, a team from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, led by epidemiologist Jared Reynolds, tracked the emergence of resistance to the drug ceftriaxone in Salmonella isolates collected from human patients by the federal National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS). When you think of Salmonella infection, you might think of gut disturbance that runs its course after a few days. But Salmonella can also cause very serious invasive disease, so the ability to shut an infection down with antibiotics is crucial. Ceftriaxone is one of the few remaining drugs that performs reliably, and yet ceftriaxone resistance in Salmonella has been increasing, making cures more difficult to achieve.

The group looked for evidence of ceftriaxone resistance between 1996 and 2010, and noted that it has been rising, from 0.2 percent of isolates collected in the NARMS program in 1996 to 2.8 percent in 2010. Some of the isolates were extremely drug-resistant, not responding to seven different families of antibiotics, including the one that ceftriaxone belongs to. Something else odd: The broad category of Salmonella has a number of serotypes within it, and different serotypes are associated with different foods, such as Salmonella Newport with beef, for example, and Salmonella Heidelberg with chicken. Resistance in Salmonella Newport is trending down after a peak between 1998 and 2002, the group noted. But the incidence of resistance in Salmonella Heidelberg has been rising rapidly since 2008, and no one can yet say why.

Also:

A team from the European Union performed similar analyses using data from the European Antimicrobial Susceptibility Surveillance in Animals (EASSA) system, a surveillance project that is similar to NARMS in the U.S. They looked at antibiotic resistance in E. coli and Salmonella found in cattle, pigs and chickens. The study covered 10 countries, and the results were variable across countries. Generally, though, the team found that bacteria taken from the animals at slaughter exhibited high rates of resistance to older antibiotics, and diminished susceptibility, but not yet frank resistance, to newer drugs. Oddly, the researchers noted, resistance in chicken and pigs to the drug chloramphenicol was high (16 percent of samples) despite the drug having been banned for years.

Pushing the research objective from animals as they are being slaughtered to the meat those animals become, a team from Portugal updated an analysis of retail beef, chicken and pork that they did 7 years ago. They found that 87 percent of their samples carried resistance to at least one antibiotic, with tetracycline being the most common. A nationwide program aimed at controlling Salmonella succeeded in reducing incidence of one important subtype, Enteriditis — but, the researchers said, it was replaced by the subtype Typhimurium, which tends to be more resistant.

A team from Australia tackled the difficult question of why poultry in that country carry E. coli that exhibit resistance to the drug class fluoroquinolones (such as Cipro), given that Australia has never permitted fluoroquinolone use in poultry raising. In a small study, they found that 30 percent of isolates which carried fluoroquinolone resistance also exhibited resistance to the drugs amoxicillin, gentamicin, tetracycline and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, which are allowed in poultry there. They found that the resistance genes all resided on the same genetic mobile element. They hypothesize that use of the legal poultry drugs is driving the emergence of resistance both to the legal drugs and to fluoroquinolones. The fluoroquinolone ban was intended to protect the drug for use in human infections, but the the existence of this “co-selection” suggests the drugs’ usefulness could be undermined nonetheless.

A multi-national team from Japan and Thailand explored the effect of antibiotics on shrimp farming by examining E. coli collected from farm waters and from shrimp taken to market. More than 17 percent of the bacterial samples were resistant to tetracycline, and many of the samples were multi-drug resistant.

Finally, researchers from Detroit and Rochester, Michigan, wanted to investigate whether antibiotic-resistant bacteria on food were creating human health problems. They examined retail lettuce for bacteria known to cause human disease and checked whether those bacteria were drug-resistant. They were, in fact, multi-drug resistant — and they were almost identical to resistant strains of the same bacteria that were causing infections in patients in two Michigan health care systems.

Flickr/Robert Couse-Baker/CC

September 12, 2012

“Superbug” NDM-1 Found In US Cat (ICAAC 3)

News from the ICAAC meeting: The “Indian superbug” NDM-1 — actually a gene which encodes an enzyme which confers resistance to almost all known antibiotics — has been found for the first time in a pet, somewhere in the United States.

When you consider the close contact we have with our pets — letting them lick us, smooching them on the head, allowing them to sleep on the bed — you’ll understand why this could be such bad news.

The finding was announced by Dr. Rajesh Nayak, a research scientist with the Food and Drug Administration’s National Center for Toxicological Research in Jefferson, Ark. (The research was carried out by Dr. Bashar Shaheen, a post-doc in Dr. Nayak’s lab.) The gene (technically blaNDM) was found in isolates of E. coli that they received from Dr. Dawn Boothe of Auburn University — part of a project, Nayak said, in which Boothe receives bacterial samples from veterinary laboratories all over the United States. Of the 100 isolates they received from Boothe, six — all from a single animal — contained NDM-1. (Update: Dr. Nayak has contacted me to say that he misunderstood my questions in our conversation, and wants to emphasize that it is not known whether the isolates came from a single, or several, animals.)

A quick recap, in case NDM-1 is new to you: The gene and the enzyme it encodes were first identified in 2008 in Sweden, in a man of Indian origin who had gone home to India, was hospitalized, recovered, and then was hospitalized again in Sweden. The Klebsiella found in the man’s urine was resistant to a huge array of drugs, including a last-resort category reserved for very serious infections that are known as carbapenems. The bacterium was susceptible to only two drugs, one old and toxic, the other new and not effective in all tissues of the body.

In 2009, bacteria containing the NDM-1 gene — which travels on several plasmids, pieces of DNA that can move easily between organisms — were found in the United Kingdom, and its Health Protection Agency put out a national alert. In 2010, bacteria containing NDM-1 were found in the United States for the first time, in three US residents living in three different states.

What the original patient, the US patients and most of the UK cases all had in common was ties to India and Pakistan: medical treatment (either emergencies or elective surgery), family ties, or travel back and forth. The identification of the gene with South Asia — the acronym stands for “New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase” — ignited a political storm within India, with lawmakers claiming that alarm over the bug was motivated by Western jealousy of India’s burgeoning medical-tourism industry. The furor got worse when the original researchers published studies of patients in South Asia, demonstrating that organisms containing the gene were not confined to hospitals but circulating widely in everyday life, and also analyses of water from New Delhi that showed the bug was moving through the water supply. Meanwhile, NDM-1 continued to spread, to more than a dozen countries so far.

The NDM-1 story has been long and contentious (my archive of posts is here), but from the first, two things have been clear. However the political battles fall out, medicine views the emergence of this gene as a catastrophe, because it edges organisms to the brink of being completely non-responsive to antibiotics, as untreatable as if the infections were contracted before the antibiotic era began. And because the gene resides in organisms that happily live in the gut without causing symptoms, NDM-1 has been a hidden catastrophe, crossing borders and entering hospitals without ever being detected.

And now, according to Shaheen and Nayak’s finding, possibly entering households and families in the same covert manner.

I spoke to Nayak after his ICAAC presentation Tuesday. He said that very little is known about the source of the bacterial samples, including the identity of the family and the cat. “The reason why we don’t know is these were not collected by us, and they were not collected by Dr. Boothe; they were collected by veterinarians,” he said. “So a family comes in, says ‘My cat is not feeling well,’ and the veterinarian collects blood, urine, whatever, and sends them in. There is no history associated with them.”

The timing of the sample is perplexing, he agreed. The isolates were received between 2008 and 2009 from the labs where vets sent them, meaning that the NDM-1 in the unknown cat was collected at the same time as the earliest recognition of the resistance factor in Europe, and at least a year before NDM-1 was perceived in the United States.

He emphasized that it isn’t known whether the cat passed NDM-1 on to its family (or, conversely, whether the family were responsible for giving the bug to their pet). If that happened, it would not be the first time that bacterial traffic between pets and their humans has made one or the other sick. There is a long literature of MRSA passing back and forth between people and their cats and dogs, in some cases making the humans sick and in some cases making the animals very ill. (Coincidentally, this also was discussed at ICAAC by Dr. Tara Smith of University of Iowa, at almost the same time that Nayak was presenting his work.) And Nayak’s group actually made the NDM-1 finding while following up two pieces of research they published last year about organisms in pets which had the resistance pattern ESBL — troubling, but still susceptible to carbapenems, and thus one step away from NDM-1.

“Carbapenem resistance is such an important issue,” Nayak told me. “Carbapenems are the last line of defense. And companion animals are so close to humans; what if there is a transfer from one to another? It is possible, that is all I can say; it is a distinct possibility.”

Flickr/ScottHughes/CC

September 11, 2012

E. Coli Behaving Badly: Hospitals, Travel, Food (ICAAC 2)

A quicker post today from the ICAAC meeting because there’s lots of news coming down this afternoon. At a conference like this, where the focus is on new behavior of pathogens and new drug compounds to contain them, there is a natural focus on emerging antibiotic resistance. Out of the first two days of (hundreds of) papers and posters, here are just a few unnerving reports.

Infections with multi-drug resistant E. coli — known by the acronym ESBL for “extended spectrum beta-lactamase,” indicating resistance to penicillins and cephalosporins — have been assumed to be a hospital phenomenon. Hospitals are where people become sick and debilitated enough to be vulnerable to these organisms, and also where patients and health care workers are more likely to spread the organism around. But an analysis by Yohei Doi of the University of Pittsburgh and a multi-national team shows that is no longer the case. They surveyed records from five hospitals across the United States (in New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Texas and Iowa), and identified 291 cases of ESBL E. coli infection over 12 months — but also found that 107 of the patients, or 37 percent, had acquired their infections before they entered the hospital. In other words, multi-drug resistant E. coli is now spreading in the everyday world, in an undetected and untracked way.

More than half of the cases the Doi team found were due to a specific strain of E. coli known as ST131, which microbiologists have been keeping an eye on because it emerged only a few decades ago and quickly became a dominant strain. A project by researchers from Denmark’s Statens Serum Institute and the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center demonstrates why that dominance is concerning. The groups examined a World Health Organization research center’s collection of E. coli isolates that stretched from 1968 to 2012. Of three isolates from 1968, soon after the clonal group was first spotted and close to when it presumably emerged, one was already multi-drug resistant. Over the decades, the organism has collected additional resistance factors. The group say: “Most of the … ‘recent’ isolates (2005-2011) were extensively multi-drug resistant, i.e., resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, ciprofloxacin, nalixidic acid, sulfamethoxazole and tetracycline.”

Finally, a team from the Netherlands examined the rapid emergence of ESBL E. coli in that country — a particular puzzle, because the Netherlands has strict regulations limiting which antibiotics can be used when, written in hopes of slowing down the emergence of resistance. As a result the Netherlands has one of the lowest rates of antibiotic use in humans in Europe. Nevertheless, when the researchers examined fecal samples that were volunteered by 1,713 Amsterdam residents living at home — that is, not hospital patients — they found that 8.5 percent were ESBL. That is, these community E. coli were resistant to penicillins and cephalosporins — and also in many cases to gentamicin, co-trimoxazole and Cipro.

Knowing that antibiotic use is kept to low levels — and therefore that there ought not to be selective pressure that would drive the emergence of resistance — the group looked for other ways that selective pressure might be being applied. They found two. I’ll quote from a statement they released to media attending ICAAC:

The 8.5 percent resistance… is approximately the same as we found a few years ago in the community in Spain and France, two countries where antibiotic use in general and resistance rates in hospitals are much higher than in Dutch hospitals. The prudent use of antimicrobials in the Netherlands contrasts with a very high use of antibiotics in food-producing animals. In the questionnaires, we have asked about antibiotic use, travel history and eating habits… The question remains whether the rise is due to travel to countries with higher resistance rates or to contamination through the food chain.

E. coli: PHIL, CDC

September 10, 2012

The Outdoors Hates You: More New Tick-Borne Diseases (ICAAC 1)

This week I’m at ICAAC (the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy), a massive infectious-disease and drugs meeting that is sponsored every year by the American Society for Microbiology. ICAAC is an unabashed scary-disease geekgasm, the kind of meeting at which the editor of a major journal tweets from one room, “‘Modern medicine will come to a halt’ in India because of catastrophic multi-drug resistance” while a microbiologist alerts from another: “Rat lungworm traced to salads on a Caribbean cruise. Snails had apparently gotten to the greens.”

Good times.

Meanwhile, I was learning more about ticks.

The news last week was of a new tick-borne illness recently identified in Missouri, and of how it demonstrates the way that tick-borne infections are under-appreciated by medicine and public health, and even more by the general public. In addition to the new Heartland virus, I mentioned two other tick-borne diseases that had been identified in the past two years.

It turns out, though, that was an under-count. The news Sunday from ICAAC is that tick-related illnesses are even more common than they appear.

Dr. Bobbi Pritt, the laboratory director of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., unfolded a disease detective story that started in the summer of 2009 with two men who liked the outdoors, and two astute lab technicians. The men, a 54-year-old and a 23-year-old who had both been out in the woods in Wisconsin, had fevers, fatigue and headaches, and a history of tick bites; the 23-year-old, who had received a lung transplant for cystic fibrosis, was more seriously ill and had to be hospitalized. The technicians noted that the men’s disease was most like erlichiosis — but the tick that carries that tick-borne illness is not present in the upper Midwest. Months later — after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had sent a pair of investigators, after involving epidemiologists from the US military who had been studying illness in the residents of bases nationwide, after trapping mice and grinding up hundreds of ticks — the group realized they had found a new tick-borne illness. It was an Erlichia – though it is so new that it does not yet have a name — but it was carried by a tick species that had never been associated with that organism before. Forty-two people have been sickened by it so far. “This is not a benign disease,” Pritt warned.

Meanwhile, Dr. Peter Krause, a senior research scientist at the Yale schools of medicine and public health, described yet another formerly unknown tick-borne disease, one that is more like Lyme disease but is caused by a newly identified relative of the Lyme organism called Borrelia miyamotoi. The illness that results is a severe and sometimes fatal relapsing fever. But unlike other relapsing fevers already known to occur in the western United States, this one is carried by a different range of tick species: the “hard-bodied” ticks that are primarily in the eastern US and are responsible for transmitting Lyme, erlichiosis and anaplasmosis. So far, Krause said, this new disease has been most studied in humans in Russia — but ticks carrying B. miyamotoi have already been identified in the United States, in ticks and mice in the Northeast and upper Midwest.

Then, Dr. Gary Wormser of New York Medical College warned that a third tick-borne illness, deer tick virus — formerly known to affect only deer — is now emerging as a human pathogen. Two cases of encephalitis caused by it have been recorded. Wormser described a third, tragic case that he has not yet published: a 77-year-old man from upstate New York who already had several chronic illnesses was bitten by a tick in October 2010, developed a fever and lethargy a month later, slid into a coma — and died 8 months later, having never regained consciousness.

Finally, Dr. Barbara Herwaldt of the CDC reminded us that, even if these stories frighten you enough to never leave your house, you are still at risk of a tick-borne disease. To date, 159 people — “the tip of the iceberg,” she said — have been diagnosed with the tick-borne illness babesiosis after receiving a blood transfusion. Because of the lag between bite and symptoms, and because the symptoms of babesiosis — like all tick-borne diseases — could be caused by so many other things, infected donors are not successfully screened out by blood banks. And because there is no FDA-approved test for babesiosis — not just a test for blood, but not even a diagnostic test to prove infection in a patient — blood banks and even physicians are unable to say with certainly when someone is a risk and should abstain from donating.

“The bottom line is: There are too many cases; they are still occurring; this is not going away,” she said. “Infected people, and contaminated blood components, can travel much further than ticks can. Donor-screening tests are needed.”

Flickr/MattAllworth/CC

September 5, 2012

A New Tick-Borne Illness, and a Plea to Consider the Insects

A tick’s mouth parts under 40x magnification.

In the summer of 2009, two men from northwest Missouri showed up at Heartland Regional Medical Center in St. Joseph, tucked up against the Kansas border 50 miles north of Kansas City. The men were seriously sick. They had high fevers, fatigue, aches, diarrhea and disordered blood counts: lower than normal amounts of white blood cells, which fight infection, and also lower than normal platelets, cells that control bleeding by helping blood to clot. But they had none of the diseases that were high on the differential diagnosis, the list of possible causes that doctors work their way down as they try to figure out what has gone wrong: no flu, no typhus, no Clostridium difficile, and none of the serious foodborne illnesses — no Salmonella, no Shigella, and no Campylobacter.

The two men had one thing in common, though: About a week before being hospitalized, each remembered, he had been bitten by a tick.

From that memory — teased out by an alert infectious-disease physician who was called to consult on the illness of both men — has come an unnerving discovery: a heretofore unknown tick-borne illness, technically a phlebovirus, that has been named Heartland virus in honor of the medical center where it was identified.

The discovery was recounted in a “brief report” in the New England Journal of Medicine last week. The two farmers, who both recovered, are the first known victims. But local physicians, along with staff from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who helped analyze the cases with rapid whole-genome sequencing, are sure there are more. In NEJM, they point out that the cause of these two men’s illnesses was only discovered because the men were so sick that physicians needed to look hard at what was going on, and add:

Although these two patients had severe disease, the incidence of infection with the novel virus and range of disease severity are currently unknown. Given the largely nonspecific symptoms observed, this virus could be a more common cause of human illness than is currently recognized.

There are two things worth thinking about in this report. The first is that it reinforces something that we tend to forget: Significant new diseases are startlingly common. In the past 40 years, at least one per year – sometimes several in a year – has been recognized for the first time or freshly linked to a causative organism. The World Health Organization published a list in 1996 (updated by the Journal of Infection in 2000). Some highlights, counting backward: There was Nipahvirus in 1998; H5N1 flu in 1997; new variant CJD (“mad cow”) in 1996; Hendravirus in 1995; Sabia virus (the cause of Brazilian hemorrhagic fever) in 1994; and Sin nombre (the cause of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome) in 1993. Going back to 1977, a banner year, there was Ebolavirus, Hantaan virus, and also Legionella, responsible for the 1976 outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease that made people wonder whether the U.S. Bicentennial celebrations were being attacked by biological weapons.

But the other thing worth thinking about is how many of those new diseases are vectorborne, transmitted by arthropods such as ticks or by insects such as mosquitoes. Heartland is one of three new tick-borne diseases identified just in the past two years, preceded by Noerlichia mikurensis in Sweden in 2010 and severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) in China last year. In the United States, Lyme disease is thought of as the major tickborne bad actor — but over the past two years, health authorities have been coming to grips with the unappreciated toll of other tick-related diseases, including erlichiosis, anaplasmosis, STARI, and babesiosis, which is moving into the blood supply. That’s not even to mention the toll of long-standing insect-borne diseases: malaria, one of the top five infectious killers in the world, along with rapidly rising dengue.

When we indulge in cultural fascination with scary new diseases, we tend to look to the animal kingdom — bats in the movie Contagion, whose scenario was based on the discovery of Nipahvirus, or monkeys in just about any account of Ebola. Like Gulliver among the Lilliputians, we have difficulty believing we can be brought down by something we can barely see. (In some cases literally: The tick suspected of transmitting Heartland, Amblyoma americanum, is half the size of a sesame seed.) But this summer has already been marked by the largest West Nile virus epidemic since the disease was recognized in the Americas, in a new and more virulent form, in 1999. Heartland is another reminder that we seldom consider the risks from insects and arthropods, and that we should.

Cite: McMullan LK, Folk SM, Kelly AJ et al. “A New Phlebovirus Associated with Severe Febrile Illness in Missouri.” 2012. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:834-841

Photo: Flickr/SpeciousReasons/CC

August 31, 2012

CDC: First Death From “State Fair Flu”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention today reported the first death from influenza A H3N2 variant (H3N2v), the swine flu strain that has been crossing intermittently from pigs to humans since last year. The victim was an “older adult with multiple underlying health conditions,” according to the CDC, and the Associated Press fills in that the victim was a 61-year-old woman from “central Ohio’s Madison County [who] died this week… after having contact with hogs at the Ross County Fair.” In a statement, the Ohio Department of Health says that she was one of 102 cases so far in the state this year. In total, the CDC says, there have been 289 cases so far this year (with Indiana leading, at 138 cases); in 2011, there were 12. Fifteen people have been hospitalized.

The CDC has been urging people for several weeks now to consider the risk of flu in state fair pig areas, and to stay away if they are in any of several categories that tend to have diminished immune systems and thus be more vulnerable to any strain of flu: younger than 2, older than 65, pregnant, or suffering from a chronic medical condition such as asthma, diabetes, heart disease or a few others. Most of the cases have some link to state fair swine barns (though Minnesota’s two cases arose in successive weeks from visits to a live-animal market).

In state-fair barns, for those of you who haven’t been — I spent some time in the Minnesota barn while reporting Superbug the book — families effectively camp out to keep their animals company and to keep them prettied-up for judging. They may not sleep there, precisely, but the kids in particular — who may have raised the animals for 4-H, school cash or both — eat and nap and hang out all day.

(Update: The Minnesota Department of Health is now announcing that they have found three cases of presumed pig-to-human transmission at their state fair — but it isn’t from H3N2v. Instead, it’s from yet another variant, H1N2v. The three victims are a teen girl who was showing pigs and a school-aged boy and a woman in her 70s who spent a lot of time in that swine barn.)

Most agriculturally focused state fairs in the US end about Labor Day — though not all; my former CIDRAP colleague Lisa Schnirring lists some exceptions in her story today, including North Carolina, Texas and Wisconsin. (Georgia, where I live, holds its fair Oct. 4-14 this year.) For fairs that continue through fall, the CDC has written guidance for anyone exhibiting pigs or visiting them.

In most of the US, then, the immediate risk of exposure from fair animals will end soon. However, the CDC has pointed out that there has been limited person-to-person transmission of this virus in the past two years, and has written some guidance for school systems who may want to be watching for ongoing clusters of infection.

The distant concern with flu is always that it is unpredictable, and may mutate into a more infectious or more virulent form. Adding pigs into the picture always alarms public health people a little, because the immunoanatomy of pigs’ lung epithelium is similar to humans’, allowing pigs to possibly serve as a “mixing vessel” for reassorting strains of flu. While concern over the H3N2v outbreak has seemed muted, it’s clear the CDC and the rest of the public health establishment do not take it lightly; 10 days ago, for instance, the CDC published standards for “enhanced surveillance” for any laboratories examining isolates from this flu.

With luck, and with deference to the victims — especially this sad death in Ohio — the H3N2v will remain a curiosity rather than become a source of alarm. But even so, it is yet another of the periodic reminders we get, that flu should never be taken for granted.

Update: Just as I hit the button on this, supreme flu reporter Helen Branswell of the Canadian Press published a piece emphasizing the concerns over transmission as kids return to school. Separately, I asked on Twitter for any sightings of blog posts on H3N2v, as I hadn’t seen any. The loose consensus is that the indefatigable Mike Coston of Avian Flu Diary is the only blogger to examine it this far. If you saw others, please let me know. Oops: Profound apologies to Crawford “Crof” Kilian, who has been covering it as well.

Flickr/Edmittance/CC