Steve Turtell's Blog, page 2

April 27, 2013

Roaches and rats and mice Oh My!—The Front Porch, 1980-1981

I was glazing cheesecakes, carefully brushing boiled marmalade over a starburst pattern of paper-thin orange slices, when a rat darted by. It hid beneath the knee-high gas burners where Kwabana stirred soups in four-foot tall stockpots. Kwabana, a cheerful, always smiling Ghanaian, had to stand on a milk crate and use metal oars to keep the Manhattan Clam Chowder, Chile con Carne, and Scotch Broth from sticking to the bottom.

“Psst. Kwabana!” I pointed down at the tail sticking out. It was the same disgusting scab-red as a pigeon’s foot.

Kwabana knew what to do. He pointed to the tail and hissed “Herman!” to Uzo, his Nigerian cohort working at an identical row of stockpots directly opposite. Uzo noiselessly laid an empty pot on its side on the floor. He then repeated the signal to Miguel, the Mexican dishwasher behind him. Miguel yelled across the room to Manny, the Puerto Rican sandwich man: “Manny! Block the doors! Herman!” Manny’s counter had a window he used to pass sandwiches through so waiters needn’t enter the kitchen for every order. It kept down on foot traffic in a crowded room, but it also meant diners could sometimes hear the kitchen talk. Hence “Herman.”

Herman didn’t work with us; outside it was code for roaches and one waiter might tell another “I saw Herman at Table Four.” In the kitchen it meant mice and rats. The healthy specimen now on the march was a half-foot long, not counting the tail.

Miguel stepped away from the dishes piled in the sink and Manny abandoned his sandwich counter. They grabbed brooms. If the rat got to the middle doors just as a waiter or Eudes, the Guyanian bus boy came through, it had a straight path to the center aisle of the dining room. I faced those doors. When they opened, I could see all the way to the front, and watch customers come in from E. 17th Street.

With Miguel and Manny in position, Kwabana grinned and stamped his foot. The rat darted into the middle of the room. He and Uzo blocked its retreat. It ran at Manny, who knocked it towards the sink with a broom and Miguel expertly putted it into the stockpot that Uzo quickly righted and covered. I stayed back by the ovens, not wanting to take part in the execution by boiling water that awaited it.

Crisis averted.

It was lunch hour, our busiest time: waiters rushed in and out with orders and every table was occupied with office workers from around Union Square, older regulars who lived in Gramercy Park, and most famous of all, Margaret Hamilton, the Wicked Witch of the West herself, who occasionally dined on The Front Porch’s soups and sandwiches.

She always sat in the back of the room, close to the kitchen, at a table for one. A very private person, she didn’t want to hear the whispering that arose when people recognized her, which someone often did. Tablemates were told. Then those at the neighboring tables noticed, and soon the whole room was transformed into a small dinner theater audience enjoying the performance of a wizened, well-dressed woman chewing a morsel of Curried Chicken Salad on Toasted Whole Wheat and washing it down with a spoonful of Mulligatawny. She cut the sandwich with a knife and fork—but I may be confusing Ms. Hamilton with another regular, also a shabby genteel type, who dabbed at the corners of her mouth with a napkin covered forefinger and carefully moved her fork to her other hand, or whatever the protocol is for Formal American Table Manners.

Gramercy Park was one of the last outposts of Shabby Genteel that still existed in Manhattan in the early 80s. And genteel, shabby or not, would knock over tables as vigorously as barroom brawlers at the sight of a rat sauntering down the aisle of their favorite lunch spot. Which would now be their former favorite. Which would mean we were all out of a job. Which would mean . . . well we couldn’t allow that to happen; hence the occasional game of rat hockey which Kwabana enjoyed so much. When I later read Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London I thought of the filthy kitchen I’d worked in every day for over a year. In a dozen kitchens in as many years, The Front Porch was the only one that came close to Orwell’s descriptions.

Once the rat was dispatched, we all went back to work. But we’d seen two rats already that month; I decided to speak to the owner. I’d taken the Board of Health’s food protection course for my job at HMS Express and knew that rats came out during the day only if they can’t get something to eat at night—including each other. I pictured swarms behind the walls.

My very first day on the job, I’d tilted a trash barrel to put in a new liner and a rat rushed up. I leapt back and watched it scurry under a counter; it disappeared into a crevice behind the mixer. Within the first week, on my way home, a roach crawled over my shirt collar, onto my arm and then up pole I held on the No. 4 train. It had burrowed into my clothes after I changed into dirty white linens I’d worn twice already. This was not something I could explain to the horrified passenger who looked at me with contempt I can still feel today. Within a month, I’d managed to convince the owner that we all required clean linens—every day, something I’d assumed was standard in even the greasiest diner. Once he provided them, he liked to come into the kitchen and admire us, and the waiters kept remarking on how clean we all looked. Kwabana preened; the starched white apron went around his waist, forming a smooth column from his chest down to his sneakers. Manny said he looked like a tall glass of milk with a fly in it.

I’d been successful with the linens; I was now prepared to threaten him with the Board of Health if he didn’t fumigate. I had to be the one to ask. I was not in charge, but no one else in the kitchen had the same leverage. The owner wouldn’t listen to Kwabana, Uzo, Eudes, Manny or Miguel because he knew he had them all by the balls and took advantage of it, paying them much less than he did me although their work was not much different than mine.

Kwabana had a degree in engineering but without a green card he was reduced to cooking soups. He’d lived in Paris, where he’d also worked in restaurants. He mocked American ignorance of life in modern Africa. “Yah, Steve. In Africa? Where we live in the trees like monkeys, yah?” Then he’d laugh, and put all his considerable strength into moving the heavy metal oar through a thick stew, dancing in place as he stirred and stirred with a circular motion.

Uzo had the same problem. He lived with his wife Chioma and his daughter Chi in Queens. Uzo was a writer; he’d been a playwright in Lagos. He came to New York to earn a doctorate in economics at The New School, hoping to return and teach in university. He let me read a few of his plays. My favorite was Back to Traditional Religion in which a bus driver convinces passengers on their way to a service not to abandon the faith of their ancestors and to ignore the Christian preachers who are threatening them with Hell. He also showed me the first chapter of a memoir. It described a young boy thrust into a new tribe and adjusting to its strange and frightening customs and ideas. At the end of the chapter the reader discovers that the new tribe is the Roman Catholic Church. He asked me for American writers he should read. I gave him a Penguin paperback Leaves of Grass. He and Chioma were impressed. She asked him “Who is this man? Who is it who writes like this?” Uzo was the most open with me. I was honored when he invited me to Chi’s twelfth birthday party. He told me about his family at home and his father-in-law, whom he loved.

“Oh, Steve, He is so jovial. He will invite you into his house and offer you cola. You will have a good time when you visit him. He is a most happy man.”

Manny was from Puerto Rico and therefore a citizen by virtue of the Jones Act (1917)—but he had a wife and two children; he needed the job. He was so frightened of losing it that he once got down on his knees and started polishing the owner’s shoes with his dishcloth in a spontaneous gesture of submission. I felt for him—the subway fare had just increased from $.50 to $.60. I could walk to and from work, but I remember Manny calculating what the extra $1.00 per week for his five round trips from the Bronx would do to his food budget. Even back then, $4.00 a month meant something to $2.90/hr. minimum wage workers, every dime counted. Manny grossed just over $100.00 per week, which had to support a family of four, while I took home $225 after taxes and was single.

Miguel was Mexican and sent money home; how I could never figure out. What could he possibly have left over?

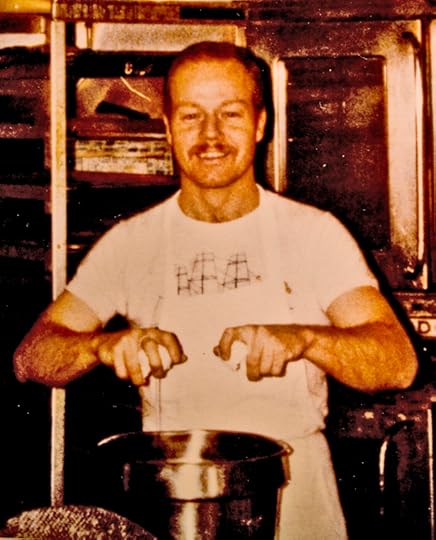

Uzo dominated the kichen. He and Kwabana joked with each other all day long, and both liked to tease Eudes, a recent convert to fundamentalist Christianity. Eudes was very proud and rarely backed down. I brought a camera in once; he stood up straight and posed as if the picture would be published as a formal portrait in a newspaper. He believed in his eventual success in America as his name meant “riches.” He argued with Uzo all the time, attempting with stiff English to defend his beliefs against former seminarian Uzo’s theologically sophisticated questions. What, Uzo wanted to know, was Eudes’ opinion of transubstantiation? When Eudes didn’t reply and Uzo asked him about dinosaurs and the age of the earth, Eudes shouted “You must shut your mouth! You do not know what you are talking about. You do not know anything. You do not know!” He was sometimes speechless with anger and then six-foot four Uzo, who towered over five-foot six Eudes, lectured him until Eudes finally walked away, refusing to listen. Kwabana’s method was simpler—he just invited Eudes to join him on his next trip to “Harlem River”—the prostitute he sometimes visited with Murphy, another Guyanian. Murphy was much more relaxed and Americanized than the others; he liked to brag about going to Studio 54. He helped Rafael, the Dominican driver, deliver desserts and soups to the two satellite branches on the Upper West Side and the West Village. He also let me know when Rafael started cutting out early, leaving me to wrap and store everything I’d cooked and baked, which was Rafael’s job.

We were a mixed, international crew—one Caucasian American, one Nigerian, two Ghanaians, two Guyanians, one Dominican, one Mexican, and one Puerto Rican—but mostly we all got along—and I was only hired because they’d insisted that of all the applicants for the job whom Karen the restaurant manager interviewed, I was the one they wanted.

Uzo had spoken for them: “This is the man you should hire. Listen to me, Karen. I tell you, this is the man!” When I thanked Uzo, he explained, “Ah, Steve. You were the only one who asked our names. You came back a second time and you had them! You had our names!” I told him that it was hard to forget such distinct names as Kwabana, Uzo, Eudes and the even more oddly named Murphy. Karen also added that during my first interview “You came on like gangbusters.”

I’m sometimes amused, but mostly embarrassed by my youthful arrogance and bluster. Standing in a line of fifteen other hopefuls for a baking job once, I loudly told them all “You may as well stop wasting your time and go home. I’m getting this job.” And I did. But it wasn’t all bluster. The foodie revolution in New York was still only beginning. The Age of Artisanal Bread hadn’t arrived. If you wanted a good baguette, unless you lived near a good bakery, you might have to make it yourself. There were not many non-union shops in New York which used only fresh, high quality ingredients and where everything was done by hand: pears and apples not out of a can but peeled, cored, and sliced; pie crusts mixed and individually rolled with a stick pin; sweet butter, not margarine or shortening, that came in twenty-five pound blocks; and quarts of real heavy cream—not “whipped topping”—brought to full volume with a ten- inch wide balloon whisk and delicately sweetened with confectioners sugar. I’d worked at several of them. I had no formal training but experience counts and while I never once considered my ten years as a baker a career, in retrospect it was one—I suppose I thought so little of it because, back then, I hated it.

From my journal:

Tues. Nov. 4th, 1980

In all the years I’ve kept this journal I don’t think I’ve ever mentioned more than in passing my life as a baker. And this evening I see clearly why I’ve never mentioned it. I hate it so completely, and once I leave work for the day, need to forget it so thoroughly that writing about it would be an abuse of the hours that are mine, and not devoted to exhausting efforts to buy those hours.

I understand my disdain but wish I’d written more. So much of this memoir is being reconstructed from memory—brief snippets like the one above calling forth memories I then tease out into scenes I write down as quickly as I can so they won’t be lost forever.

I started work at 6am and left at 2, just as the lunch rush was ending. The others arrived at 9 or 10 and we worked in staggered shifts so there was someone in the kitchen for most of the day. But in spite of being there early enough to bake and serve everything as soon as it was cool enough to slice, we froze all the cakes, pies, casseroles, soups and stews. The only things served fresh at The Front Porch were salads and sandwiches. My daily production sheet was designed to fill the gaps in a freezer stocked for as long as a week in advance.

Because I had to supply three restaurants, a typical day might include fifty quiche (three varieties), eight-six carrot breads, fifty chocolate pies, ten brown sugar cakes, two gallons of frosting, four cheese casseroles (twenty servings each), and four pumpkin cheesecakes. I’d learned how to cook in large volume at Montana Palace so this wasn’t a challenge. I wasn’t, as I’d done there many times, browning thirty pounds of onions in three huge skillets while also mixing the quiche batter across the room in an eighty-quart Hobart, the pie dough for one hundred quiche chilling in the walk-in refrigerator. The mixer I now used held twenty quarts. But the real difference was that for the first time, I wasn’t doing everything from scratch. I hated using canned fruit in pies and this, along with the owner’s obvious contempt for us all, may have contributed to the casual atmosphere in the kitchen, which I take some credit for. We were a rowdy bunch.

From my journal:

Thursday, January 15, 1981

Quiet at work on Wednesday. Murphy’s increasingly aggressive assertions of his – what else – sexual prowess and endowments. All the Africans except Eudes (who is a fundamentalist Christian) brag continually of the size and the force, almost the brutality with which they fuck. Murphy likes to mimic the activity while he brags, holding an imaginary woman by the side of her thighs and violently thrusting his crotch forward. Law-abiding Eudes looking down fiercely. This is what Murphy promises to do when he gets hold of me. “I’ll take it. I’ll take your ass man. One day. You’ll see.” He says it so seriously and it sounds so funny.

Uzo and Miguel trading insults. Uzo’s always blind to how much he really hurts Miguel. “Mr. Mike. Where did you go to school? Ah! Ah! When you have gone to high school, then you can talk to me. Don’t talk to me until you have been to school.”

Monday, January 26, 1981

Just back from work . . . I managed to get everyone else in the kitchen worked up. First Miguel and I started flinging canned soggy peach halves at each other. And he escalated to whole plums – one of them hit me right on my left nipple, leaving when I peeled away the smashed plum, a creeping purple blotch. This called for serious retaliation so I dumped a cup of flour onto his thick glossy black Mexican hair. It sifted down through his bangs, frosting his eyebrows, spotting his nose, and when he shook his head, working its way down the back of his neck and into his clothes. I stood in front of him laughing hysterically, holding my aching belly with both hands. It was so funny it hurt to laugh, there were tears in my eyes. I closed them to clear away the wet and when I removed my hand and opened my eyes of a blob of tuna fish splattered right above my nose.

“Fuck you Pelóna.”

Early on, Miguel had nicknamed me “Pelón”—or when he wanted to be flirtatious and contemptuous at the same time, “Pelóna”—or baldy.

“Pelóna. You want me. I got beeg muscles for you.” He flexed his chubby arms and Uzo mocked him.

“Mr. Mike. You are fat. Steve is bald, but you are fat!”

Miguel winked at me and turned back to the sink.

“Ok, Pelóna. I know. I know.”

Uzo didn’t let up.

“Mr. Mike. You are a fool. Why would Steve want to Mau-Mau with a fat man like you?”

“Fuck you, Uzo.”

Uzo laughed and continued grating twenty pounds of carrots for Ginger Carrot Soup.

“Steve. Do you want to Mau-Mau with Mr. Mike?”

Uzo dubbed gay sex, and then any sex at all, “Mau-Mau,” which he loved to shout out across the room to me.

“Mau-Mau!” became a cry heard in the kitchen all the time. Kwabana shouted it when he planned to visit Harlem River with Murphy.

There was horseplay, but serious discussion too. I asked about African politics. Idi Amin, referred to in the US press as “the Butcher of Uganda” was constantly in the news and I was shocked that to a man, they all defended him.

“You do not know what is good for Africa,” Eudes said, Uzo for once not dismissing his opinion. They also insisted, Uzo in particular, that homosexuality did not exist in their respective countries. Uzo explained why:

“If they catch you at this, they will smack your ears until they bleed!”

“Uzo that just means people are hiding out of fear.”

When Uzo saw a section of gay and lesbian books at Barnes & Noble he told me he thought “Maybe this Mau-Mau Steve talks about is real.” He marveled at my complete heterosexual virginity: “Steve, you mean you have never been in the sweet core of a woman?!” He and Kwabana offered to buy me a whore or take me to visit Harlem River.

They could not get a clear grasp of me, nor I of them.

When John Hinkley, Jr. shot Reagan, I arrived at work the next day depressed at yet another violent episode in American politics. Uzo knew me as a radical/liberal—we sometimes shared these views. He was stunned at my emotional reaction and announced to the others: “You will never catch Steve. You will never catch him!” He meant I was unpredictable. When Pope John Paul II condemned lust in marriage, Murphy and Kwabana dismissed this as foolish. Uzo insisted they hear my interpretation: “He just means you shouldn’t treat your wife only as a sex object.”

“Listen to a man of reason,” Uzo scolded.

There was one incident when miscommunication nearly destroyed any friendliness we had, and everyone in the kitchen ignored me for an entire week. Uzo convinced them that I had betrayed him to the owner and they shunned me. I’d never been shunned. It hurt tremendously.

Uzo and I both used hundreds of pounds of carrots. A fifty-pound bag sat next to the grater for Uzo to process. Manny often helped while also passing sandwiches out to waiters. Uzo and I had to be careful to take the batch that was grated for soup and not for carrot bread or vice versa. One day they got mixed up and both the Ginger Carrot Soup and the Carrot Breads had to be redone. This was expensive and required an additional produce order. It was a simple mistake—and the soup was easily fixed—which I explained to Karen—saying I’d taken the wrong batch. I wasn’t sure whose mistake it was, but I knew I could weather the fallout better than Uzo. After the fumigation crisis, the owner seemed wary of me, as if I had something on him and he had to treat me carefully. I don’t know what Karen told the owner but he came into the kitchen and started shouting at Uzo, who then blamed me. Uzo’d seen me talking to Karen, then the owner yelled at Uzo. It was obvious to him what had happened. Nothing either Karen or I said made any difference. I was a rat.

Is there a worse accusation? Is anything more painful than the silent treatment? I came to work every day hoping that when the others arrived I’d be greeted again as if nothing had happened, that we could shout “Mau! Mau!” and laugh as we worked. But they all talked to each other as if I didn’t exist, as if they could not even see me. Uzo now treated Miguel and Eudes with extra respect; he became almost courtly and they responded by taking his side. The international boundaries that had dissolved in silly banter hardened into a Berlin Wall of silence around me. The poisonous atmosphere depressed all of us. Hardest to accept was feeling that their friendliness—if it ever resumed—would always be tempered by suspicion—that they believed they’d now seen the authentic me and I could never be trusted again, that I was not one of them, not a worker among workers, but really, finally, on the side of the bosses. Just another Ugly American.

Fortunately, it lasted only a week. Soon we were all being silly and giddy again. I knew it was over when Uzo joined me in a food fight against Miguel. We cut holes in black garbage bags, covered ourselves, then snuck up behind Miguel and poured flour over his head. Uzo didn’t run away—he just stood in front of Miguel and offered himself as a target since the flour wouldn’t stick. But Miguel didn’t retaliate immediately. He waited till Uzo had his back turned and poured a cup of flour into his Afro. Some of it drifted over to Kwabana and settled on top of one of his soups. So he joined in. My “betrayal” was forgiven, swept away with the flour we had to get off the floor before either Karen or the owner walked in. We had less to worry about with Karen, who liked seeing us laughing and joking as long as the work got done. The owner rarely made an appearance—fine with us. When he did show, he hovered at the back by the doors, stared at us, and we fell silent until he turned and left. We treated him like a parent; we behaved ourselves in his presence but ridiculed him once he was safely out of view.

I left the Front Porch in May of 1981. I don’t remember why. I think the restaurant closed. I was soon working at what turned out to be my last baking job, for a boutique bakery called Here’s To The Table, on the Upper East Side. Towards the end of the summer it moved down to the South Street Seaport area on Front Street in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge: then still a vacant no-man’s land. The owner, a lanky hippy named Roger, had a blind cat, Beulah. She had the run of the kitchen, wandering aimlessly, and I sometimes tripped over her. Not fun when pulling a tray of hot baguettes out of the oven. But that was far from the worst that happened on that job.